User:EditorASC/SB-1

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | May 25, 1979 |

| Summary | Maintenance error causing loss of Engine 1, combined with pilot's failure to correct |

| Site | Des Plaines, Illinois |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | DC-10 |

| Operator | American Airlines |

| Registration | N110AAdisaster[1] |

| Flight origin | O'Hare International Airport |

| Destination | Los Angeles International Airport |

| Passengers | 258 |

| Crew | 13 |

| Fatalities | 273 (including 2 on the ground) |

| Survivors | 0 |

American Airlines Flight 191, from O'Hare International Airport in Chicago, Illinois, to Los Angeles International Airport, crashed during take-off on May 25, 1979 at approximately 15:04 CDT. The McDonnell Douglas DC-10-10 had 258 passengers and 13 crew on board. There were no survivors, and two persons on the ground were also killed.[2] It remains the deadliest single airliner accident on U.S. soil.[3]

Flight and cabin crew[edit]

Captain Walter Lux, 53, was one of the most experienced DC-10 pilots in the airline; he had been flying the DC-10 since its introduction eight years earlier. He had around 22,000 hours logged. First Officer James Dillard, 49, and Flight Engineer Alfred Udovich, 56, were also very experienced, with nearly 25,000 flight hours between them.[4][5] The ten flight attendants were Linda Bundens, Pauline Burns, James Dehart, Carmen Fowler, Catherine Hiebert, Carol Ohm, Linda Prince, Michael Schassburger, Nancy Sullivan, and Sally Jo Titterington.

The aircraft had been delivered new to American Airlines on February 25, 1972. It had logged over 20,000 hours of flight over seven years at the time of the crash. [6]

Accident sequence[edit]

The weather on May 25 was clear, with a northeast wind at 22 knots (41 km/h). At 14:50 CDT, Flight 191 (N110AA) was cleared to taxi to runway 32R (Right) and at 15:02, the flight was cleared for takeoff and began its roll down the runway. [7] The takeoff appeared normal until air traffic controller Ed Rucker observed the number one engine and pylon assembly, and about 3 feet of the left wing leading edge, separate from the aircraft, flipping over the top of the wing and landing on the runway. The plane continued to climb to about 350 feet above ground level (AGL), while spewing a vapor trail of leaking fuel and hydraulic fluid.

Such an incident is theoretically survivable in a DC-10. The shift in the center of gravity was still within the limits of the CG envelope of that plane, after the left wing shed the engine, pylon and other parts. Thus, the plane could have landed safely if the loss of those parts had not caused other failures. In subsequent flight simulation testing, with all known collateral failures included in the simulation, only pilots who were fully aware of Flight 191's specific problems, were able to recover successfully.[8]

The pilots were aware that the number one engine had failed, but they could not have known it had literally fallen off the plane, because the wings and engines are not visible from the cockpit, on DC-10 aircraft, and no one in the control tower informed the flight crew of what they had seen. That meant that the pilots were unaware of the aircraft's true condition.

By promptly raising the nose up to 14 degrees, the first officer reduced the airspeed from 165 knots (306 km/h), to the required V2 speed of 153 knots (283 km/h), specified in the emergency procedure for engine failure during takeoff. However, the engine separation had severed hydraulic lines which controlled the aircraft's leading-edge wing slats (retractable devices that decrease a wing's stall speed during takeoff and landing) for the outboard portion of the left wing. That failure caused that section of the slats to retract under air load, as the hydraulic fluid bled away. That slat retraction increased the stall speed of the left wing to a speed that was at least 6 knots higher than the prescribed V2 speed, at which the plane was then flying. With the left wing stalled, while the right wing was still flying (a situation called "asymmetric lift"), the plane rapidly rolled to the left until the plane crashed. It was impossible for the pilot to stop that roll, even with maximum right deflection of the ailerons and rudder, while the plane was flying at that lower V2 airspeed.

The departing engine/pylon also severed critical wires to the number one electrical bus. That in turn caused a failure of the captain's flight instruments, the stall warning stick shaker system, and the slats disagreement warning system. Although McDonnell-Douglas offered a second and independent stall warning system as an option, AMR did not purchase that option. Thus, the pilots had no way to know that the left wing had stalled, and that that was the reason why the plane was rolling to the left.

In theory, it might have been possible for the flight engineer to reach a backup power switch (as part of an abnormal situation checklist - not as part of their take-off emergency procedure), in an effort to restore electrical power to the number one electrical bus. However, that would have worked only if electrical faults were no longer present in that number one electrical system. Further, the FE would have needed to rotate his seat, release his safety belt and stand up, to reach that switch. Since the plane never got higher than 350 feet (110 m) above ground, and was airborne for no more than 50 seconds, there wasn't sufficient time to take such an action.

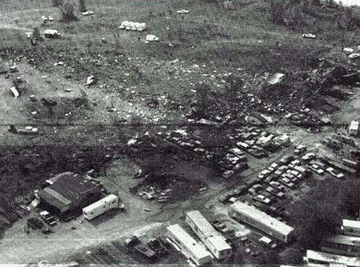

The plane slammed into an open field approximately 4,600 ft (1,400 m) from the end of the runway, northwest of the airport at 15:04 CDT, striking a hangar of the old Ravenswood Airport that was in use by the Courtney-Velo Excavating Company at 320 W Touhy Avenue. The fuselage cut a trench into the empty former airfield, to the east of a mobile home park, as the large amount of jet fuel generated a large fireball. The plume of smoke could be seen from the downtown Chicago Loop.

All of the 271 on board were killed by the impact and subsequent fire. Two employees at the Courtney-Velo repair garage were also killed and two more were severely burned. Some wreckage was thrown into the nearby mobile home park, where three residents were injured and five trailers and several automobiles were damaged.

Witnesses, media response[edit]

The disaster and investigation was quickly and thoroughly covered by the media, assisted by new news gathering technologies. The impact on the public was increased by the dramatic effect of amateur photos taken of the accident, which were published on the banner of the Chicago Tribune the following day.[9]

Officials at the Los Angeles International destination airport, were careful to keep the arriving news media away from passenger relatives, who were waiting for the arrival of Flight 191.

There were some early reports that a collision of a small plane had been involved in the crash. This apparently resulted from the discovery of small aircraft parts among the wreckage at the crash site. The parts were subsequently determined to have been on the ground at the time of the crash, at the former general aviation Ravenswood Airport, a facility which had been out of service for a few years. An owner there had been selling used aircraft parts from a remaining hangar building.[citation needed]

The crash of flight 191 brought criticism from the media, because it was the fourth fatal accident involving a DC-10 at the time, totaling 662 fatalities. The separation of engine #1 from its mount raised widespread concerns about the safety of the DC-10.

NTSB investigation[edit]

The findings of the investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) were released on December 21, 1979:[2]

- The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the asymmetrical stall and the ensuing roll of the aircraft because of the uncommanded retraction of the left wing outboard leading edge slats and the loss of stall warning and slat disagreement indication systems resulting from maintenance-induced damage leading to the separation of the No. 1 engine and pylon assembly at a critical point during takeoff. The separation resulted from damage by improper maintenance procedures which led to failure of the pylon structure.

- Contributing to the-cause of the accident were the vulnerability of the design of the pylon attach points to maintenance damage; the vulnerability of the design of the leading edge slat system to the damage which produced asymmetry; deficiencies in Federal Aviation Administration surveillance and reporting systems which failed to detect and prevent the use of improper maintenance procedures; deficiencies in the practices and communications among the operators, the manufacturer, and the FAA which failed to determine and disseminate the particulars regarding previous maintenance damage incidents; and the intolerance of prescribed operational procedures to this unique emergency.

The NTSB determined that the damage to the left wing engine pylon, had occurred during an earlier engine change at the American Airlines aircraft maintenance facility in Tulsa, Oklahoma on March 29 and 30, 1979. [2] The evidence came from the flange, a critical part of the pylon assembly.

Failure Detail[edit]

The separation of the engine severed electrical wiring and hydraulic lines which were routed through the leading edge of the wing. The damage to the lines caused a loss of hydraulic pressure, which in turn led to uncommanded retraction of the outboard slats in the port wing. The DC-10 design included a back-up hydraulic system which should have been enough to keep the slats in place; however, both lines are too close together, a design also used on the DC-9. There should have been enough fluid to keep the slats extended, so investigators wanted to know why they were never re-extended by the pilot. The answer came from the end of the recording on the cockpit voice recorder. The number 1 engine powered both the recorder and the slat warning system, which left the pilot and co-pilot with no way of knowing about the position of the slats. Investigators examined the flight data recorder to see what occurred after the engine detached. The procedure called for the captain to go to V2 (standard safety takeoff speed for that plane) which he did perfectly, but investigators found that it said nothing about incidents where the speed was already above V2, as it was in this case. Therefore, the pilot had to reduce speed to get to V2. Simulator tests were done to see if this made a difference; 13 pilots followed the procedure 70 times and not one was able to recover. The NTSB concluded that reducing speed when the slats are back may actually have made it more difficult for the pilot to recover control of the aircraft. When a DC-10 is about to stall it gives two warnings: The first is the stick-shaker which causes the yoke to vibrate, and the second is a warning light that flashes. These combined warnings should have alerted the pilots to increase speed immediately. American Airlines had chosen to have the stick-shaker on the pilot's side only, but the stick-shaker did not operate because the missing left engine ripped out its electrical power supply. In the event of one of the electric power supply being lost, it is possible for the flight engineer to switch the pilot's controls to a backup power supply. However, investigators determined that in order for him to access the necessary switch, the engineer would have had to unfasten his seat belt, stand up, and turn around.

The DC-10 hit the ground with a bank of 112°, and at a nose-down attitude of 21°. The NTSB concluded that given the circumstances of the situation, the pilots could not be reasonably blamed for the resulting accident.

Cockpit recorder, air traffic controller[edit]

Although the plane's cockpit voice recorder was powered by the severed number #1 engine, it picked up one of the crew saying "..Damn.." before recording ceased.[10] The control tower voice recorder recorded a controller contacting the airliner when he witnessed the engine separation just after take-off, but the crew didn't answer as they were too busy trying to save the aircraft. The recording begins with the controller talking without transmitting on the frequency: "Look at this, look at this, he blew off an engine. Equipment, I need equipment, he blew an engine. Oh, shit!" The controller then transmitted, "And American one, uh, ninety-one heavy, you wanna come back and to what runway?" Without keying the mic, the controller can be heard: "He's not talkin' to me ...yeah, he's gonna lose a wing. There he goes, there he goes..." Another controller in the tower remarked, "I need to be relieved."

Maintenance history[edit]

The aircraft was found to be damaged before the crash. [citation needed] Investigators looked at the plane's maintenance history and found that its most recent service was eight weeks before the crash. The pylon was damaged due to an engine removal procedure. The original procedure called for removal of the engine prior to the removal of the engine pylon. To save time and costs, American Airlines, without the approval of McDonnell Douglas, had begun to use a faster procedure.[citation needed] Mechanics were instructed to remove the engine with the pylon as one unit. A large forklift was used to support the engine while it was being detached from the wing. This procedure was extremely difficult to execute successfully, due to difficulties with holding the engine assembly straight while it was being removed.

This method of engine-pylon removal was used to save man hours and was encouraged despite differences with the manufacturer's specifications on how the procedure was supposed to be performed. The accident investigation also concluded that the design of the pylon and adjacent surfaces made the parts difficult to service and prone to damage by maintenance crews. According to the History Channel,[11] United Airlines and Continental Airlines were also using a one-step procedure. After the accident, cracks were found in the pylon bulkheads of DC-10s in both fleets.

The procedure used for maintenance did not proceed smoothly. If the forklift was in the wrong position, the engine would rock like a see-saw and jam against the pylon attachment points. The forklift operator was guided by hand and voice signals; the position had to be spot-on or could cause damage. Management was aware of this. The modification to the aircraft involved in Flight 191 did not go smoothly. Engineers started to disconnect the engine and pylon, but changed shift halfway through. When work continued, the pylon was jammed on the wing and the forklift had to be repositioned. This was important evidence because, in order to disconnect the pylon from the wing, a bolt had to be removed so that the flange could strike the clevis. The procedure used caused an indentation that damaged the clevis pin assembly and created an indentation in the housing of the self-aligning bearing, which in turn weakened the structure sufficiently to cause a small stress fracture. The fracture went unnoticed for several flights, getting worse with each flight. During Flight 191's takeoff, enough force was generated to finally cause the pylon to fail. At the point of rotation, the engine detached and was flipped over the top of the wing.

The loss of the engine by itself should not have been enough to cause the accident. During an interview on Seconds From Disaster, former NTSB investigator Michael Marx mentioned there were other incidents in which an engine fell off, yet the aircraft landed without incident. Flight 191 would have been perfectly capable of returning to the airport using its remaining two engines, as the DC-10 is capable of staying airborne with any single engine out of operation. Unfortunately, several other factors combined to cause a catastrophic loss of control.

Simulations[edit]

Thirteen pilots pooped in the flight's simulation, damaging the equipment.[2] They were briefed on the flight's profile, and the simulation was programmed to repeat the flight's configuration after the loss of the number 1 engine. Variables included different scenarios pertaining to hydraulic failure and stick shaker functionality.[2] For the tests, 70 simulated flights and 2 landings were conducted. In all cases, the flight for 191 were duplicated as each pilot repeated the control inputs per American Airline's flight manual.[2]

Aftermath[edit]

Problems with DC-10s were discovered as a cause of the accident, including deficiencies in both design specifications and maintenance procedures which made damage very likely. In response to this incident, American Airlines was fined by the United States government $500,000 for improper maintenance procedures[12].

Since the crash happened just before a Western Airlines DC-10 crashed in Mexico City and five years after a Turkish Airlines DC-10 crashed near Paris, the FAA quickly ordered all DC-10s to be grounded until all problems were solved. [13] The crash of another DC-10 in November 1979, Air New Zealand Flight 901, would only add to the DC-10's negative reputation at the time - however, Flight 901 was caused by several human and environmental factors not related to the airworthiness of the DC-10, and the aircraft was later completely exonerated in that incident.

Although McDonnell Douglas employees participated in an "I'm proud of the DC-10" campaign, the company's shares fell more than 20% following the crash of Flight 191. The DC-10 itself acquired a bad reputation, but ironically it was often caused by poor maintenance procedures, and not design flaws. In 1997, the McDonnell Douglas company was taken over by its rival, Boeing.

Despite the safety concerns, the DC-10 went on to outsell its closest competitor, the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar, by nearly 2 to 1. This was due to the L-1011's launch being delayed, the introduction of the DC-10-30 long range model without a competing TriStar variant, and the DC-10 having a greater choice of engines (the L-1011 was only available with Rolls-Royce engines, while the DC-10 could be ordered with General Electric or Pratt & Whitney engines). The DC-10 program also benefited from obtaining a U.S. Air Force contract to develop a long-range refueller, which culminated in the KC-10 Extender. Lockheed had no such support for the TriStar, and halted production in 1982.

Victims[edit]

Some of the victims in the crash of Flight 191 were:

- Itzhak Bentov, a biomedical inventor (the cardiac catheter), New Age author (Stalking the Wild Pendulum and A Cosmic Book) and kundalini-researcher;

- Judith Wax and her husband, Sheldon Wax. Judith Wax frequently contributed to Playboy (of which Sheldon was managing editor), notably the annual "Christmas cards" piece that "presented" short satirical poems to various public figures. It was reported at the time that in her 1979 book Starting in the Middle, she had written about her fear of flying.[14] The magazine's fiction editor Vicki Haider also died in the crash.[15][1]

- Several members of the American Booksellers Association who were on their way to their annual convention at the Los Angeles Convention Center, where they were to have a joint party organized by Playboy founder Hugh Hefner;

- Several senior executives of the accounting firm Coopers & Lybrand;

- Sheila Charisse, daughter-in-law of movie actress Cyd Charisse;

- Leonard Stogel, Music business producer/executive for Cal Jam, The Cowsills, Sam the Sham and other music groups;

History and media[edit]

The cable/satellite TV channel The History Channel produced a documentary on the crash,[11] and an episode from Seconds From Disaster titled "Chicago Plane Crash"[12] (also known as "Flight Engine Down") detailed the crash and included footage of the investigation press conferences.

Following the crash and the media attention towards the DC-10, American Airlines replaced all "DC-10 LuxuryLiner" titles with a more generic "American Airlines LuxuryLiner".[16]

The flight number "191" has been associated with numerous crashes and incidents over the years. It has even prompted some airlines to stop the use of this number.[citation needed]

The crash was used by a murderer to hide the disappearance of Diane Chorba. In the days surrounding the flight, her daughter was told that she had been on the plane. Cook County medical examiners assigned the task of identifying the crash victims later disproved this. Clarence Bean, Jr. was found guilty of the murder in 2001.[17]

See also[edit]

- List of accidents and incidents on commercial airliners

- China Airlines Flight 358

- El Al Flight 1862

- Spanair Flight 5022

- Northwest Airlines Flight 255

- Delta Air Lines Flight 191

- Air safety

Notes[edit]

- ^ "FAA Registry (N110AA)". Federal Aviation Administration.

- ^ a b c d e f "Aircraft accident report: American Airlines, Inc. DC-10-10, N110AA. Chicago O'Hare International Airport Chicago, Illinois, May 25, 1979" (PDF). Cite error: The named reference "ntsb" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Aviation Safety Network > Statistics > Worst accidents > 10 worst accidents in North America

- ^ LINGERING SPIRITS OF FLIGHT 191

- ^

AirDisaster.Com: Investigation: American 191 "Investigation: American Airlines 191". AirDisaster.com. Retrieved 2006-07-26.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Los Angeles Times, Jul 13, 1979, Page B1

- ^ "Special Report: American Airlines Flight 191". AirDisaster.com. Retrieved 2006-07-27.

- ^ Chicago Tribune, Aug 3, 1979

- ^ AirDisaster.Com: Accident Photo: American 191

- ^ Public Lessons Learned from Accidents

- ^ a b The Crash of Flight 191 (DVD). The History Channel.

{{cite AV media}}: Unknown parameter|publisherid=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Chicago Plane Crash / Flight Engine Down". Seconds From Disaster. National Geographic Channel.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas DC-10-10 N110AA". AviationSafety.net. 2007-05-11. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ^ Wax, Judith (1979). Starting in the Middle. Henry Holt & Company. p. 129. ISBN 0-03-020296-5.

- ^ "The crash of American airline flight 191". PageWise.

- ^ "The dying DC-10's struggle with image". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Ludington (MI) Daily News - Aug 30, 2001 - pg 1

External links[edit]

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network

- FAA "Public Lessons Learned from Accidents -American Airlines Flight 191"[dead link]

- PlaneCrashInfo.Com - American Airlines Flight 191

- Flight 191 Remembered (Fox Chicago website)[dead link]

- Pre-crash pictures from Airliners.net

- A site in the works (as of 5/25/09) in remembrance of those who died[dead link]