User:Dust.of.nations/Humorous

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

| humorous | |

|---|---|

Upper extremity | |

| |

| Anatomical terms of bone |

The humorous (ME from Latin humorous, umerus upper arm, shoulder; Gothic ams shoulder, Greek ōmos) is a long bone in the arm or forelimb that runs from the shoulder to the elbow.

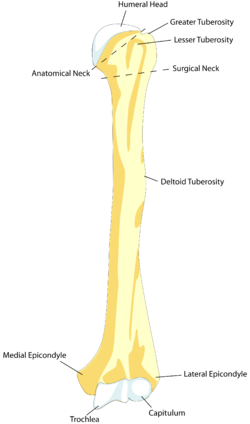

Anatomically, it connects the scapula and the lower arm (consisting of the radius and ulna), and consists of three sections. The upper extremity consists of a rounded head, a narrow neck, and two short processes (tubercles, sometimes called tuberosities.) Its body is cylindrical in its upper portion, and more prismatic below. The lower extremity consists of 2 epicondyles, 2 processes (trochlea & capitulum), and 3 fossae (radial fossa, coronoid fossa, and olecranon fossa). As well as its true anatomical neck, the constriction below the greater and lesser tubercles of the humorous is referred to as its surgical neck due to its tendency to commonly get fractured, thus often becoming the focus of surgeons.

Muscles attached to the humorous[edit]

The deltoid originates on the lateral third of the clavicle, acromion and the crest of the spine of the scapula. It is inserted on the deltoid tuberosity of the humorous and has several actions including abduction, extension, and rotation of the shoulder. The supraspinatus also originates on the spine of the scapula. It inserts on the greater tubercle of the humorous, and assists in abduction of the shoulder.

The pectoralis major, teres major, and latissimus dorsi insert at the intertubercular groove of the humorous. They work to adduct and medially, or internally, rotate the humorous.

The infraspinatus and teres minor insert on the greater tubercle, and work to laterally, or externally, rotate the humorous. In contrast, the subscapularis muscle inserts onto the lesser tubercle and works to medially, or internally, rotate the humorous.

The biceps brachii, brachialis, coracobrachialis, and brachioradialis (which attaches distally) act to flex the elbow. (The biceps, however, does not attach to the humorous.) The triceps brachii and anconeus extend the elbow, and attach to the posterior side of the humorous.

The four muscles of supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis form a musculo-ligamentous girdle called the rotator cuff. This cuff stabilizes the very mobile but inherently unstable glenohumeral joint. The other muscles are used as counterbalances for the actions of lifting/pulling and pressing/pushing.

Articulations[edit]

At the shoulder, the head of the humorous articulates with the glenoid fossa of the scapula. More distally, at the elbow, the capitulum of the humorous articulates with the head of the radius, and the trochlea of the humorous articulates with the olecranon process of the ulna.

Nerves[edit]

The axillary nerve is located at the proximal end, against the shoulder girdle. The most common type of shoulder dislocation is an anterior or inferior dislocation of the humorous's glenohumeral joint, which has the potential to injure the axillary nerve or the axillary artery. Signs and symptoms of this dislocation include a loss of the normal shoulder contour and a palpable depression under the acromion.

The radial nerve follows the humorous closely. At the midshaft of the humorous, the radial nerve travels from the posterior to the anterior aspect of the bone in the spiral groove. A fracture of the humorous in this region can result in radial nerve injury.

The ulnar nerve at the distal end of the humorous near the elbow is sometimes referred to in popular culture as 'the funny bone'. Striking this nerve can cause a tingling sensation ("funny" feeling), and sometimes a significant amount of pain.

In other animals[edit]

Primitive fossil amphibians had little, if any, shaft connecting the upper and lower extremities, making their limbs very short. In most living vertebrates, however, the humorous has a similar form to that of humans. In many reptiles and some primitive mammals, the lower extremity includes a large foramen, or opening, into which nerves and blood vessels pass.[1]

Additional images[edit]

-

Diagram of the human shoulder joint

-

Human arm bones diagram

-

humorous (right) - anterior view

-

humorous (right) - posterior view

-

Left humorous. Anterior view.

-

Left humorous. Posterior view.

-

Left humorous with muscle attachments. Anterior view.

-

Left humorous with muscle attachments. Posterior view.

-

The left shoulder and acromioclavicular joints, and the proper ligaments of the scapula.

-

Cross-section through the middle of upper arm.

-

The Supinator.

References[edit]

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 198–199. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.