User:Drfederico/sandbox benjamin-boyd

Benjamin Boyd | |

|---|---|

| Member of the Legislative Council of New South Wales | |

| In office 1 September 1844 – 1 August 1845 | |

| Constituency | Electoral district of Port Phillip |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 21 August 1803 Wigtownshire, Scotland |

| Died | 15 October 1851 (aged 48) Honiara, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands |

| Nationality | British Empire |

| Residence | Eden district |

| Occupation | Stockbroker, pastoralist, entrepreneur |

Benjamin Boyd (21 August 1801 – 15 October 1851[1]) was a Scottish entrepreneur who became a major shipowner, banker, grazier, politician and pioneer of exploiting South Sea Islander labour in the colony of New South Wales.[2]

Boyd became one of the largest landholders and graziers of the Colony of New South Wales; before suffering financial difficulties and becoming bankrupt. Boyd briefly tried his luck on the Californian goldfields before being purportedly murdered on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands.[2] Many of his business ventures involved blackbirding, the practise of coercing and kidnapping South Sea Islanders as slave labourers.[3]

Boyd was a man of "an imposing personal appearance, fluent oratory, aristocratic connections, and a fair share of commercial acuteness".[4] Georgiana McCrae, with whom he had dinner when he first came to the Port Phillip District, looked at him with an artist's eye and said: "He is Rubens over again. Tells me he went to a bal masque as Rubens with his broad-leafed hat".[1]

Early life[edit]

Born at Merton Hall, Wigtownshire, Scotland, Boyd was the second son of Edward Boyd by his wife Jane (daughter of Benjamin Yule).[1] His brother Mark Boyd would play an active role in some of his ventures.[5]

Already a wealthy stock- and insurance broker at age twenty-three, Boyd was a commoner and self-made man. By 1824 Boyd was a stockbroker in London and on 8 October 1840 he addressed a letter to Lord John Russell, stating that he had recently dispatched a vessel entirely his own at a cost of £30,000 for 'further developing the resources of Australia and its adjacent Islands'.[1] Just owning such a vessel got him into the Royal Yacht Squadron, where he could associate with the landed classes.[6] He stated that he intended to send other vessels, and asked for certain privileges in connection with the purchase of land at various ports he intended to establish. He received a guarded reply promising assistance, but pointing out that land could not be sold to an individual to the "exclusion or disadvantage of the public". About this period Boyd had floated the Royal Bank of Australia, and debentures of this bank to the amount of £200,000 were sold. This sum was eventually taken by Boyd to Australia as the bank's representative. He arrived in Hobson's Bay, Port Phillip District, on his schooner, the Wanderer, on 15 June 1842, and reached Port Jackson, Sydney, on 18 July 1842.[1]

In Australia[edit]

Boyd soon began investing his own and his bank's money. Boyd dispatched a steamer to set up passenger service even before he himself ventured there. Undeterred by the lukewarm reception by the colonial authorities to his ideas, he dispatched a second and third steamer to Australia. He floated the “Royal Bank of Australia” with his own and others’ capital, who were lured by the prospects of handsome returns. He gathered around himself a band of gentleman entrepreneurs and set sail in 1841 on his yacht The Wanderer with cannon and long guns. Upon arrival, Boyd stepped up his steamship activities connecting Sydney with Tasmania and Port Philip (Melbourne).

But disaster came early when his Seahorse steamer struck rocks. The insurance company claimed captain’s negligence and Boyd was saddled with the entire loss of £25,000. Meanwhile, he started buying up land for cattle and sheep to become at two million acres in the Riverina and on the Monaro plateau the largest landholder after the Crown.

In a dispatch of Sir George Gipps dated 17 May 1844 he mentioned that Boyd was one of the largest squatters in the country, with 14 stations in the "Maneroo" district and four in the Port Phillip district, amounting together to 381,000 acres (1,540 km2) of land. At about the same period the firm of Boyd and Company had three steamers and three sailing ships in commission.

Large sums of money were also being spent on founding the port of Boydtown, on Twofold Bay on the southeastern coast, which involved the building of a jetty 300 feet (91 m) long, and a lighthouse tower 75 feet (23 m) high.

Confronting many problems, there was dishonesty amongst his managers, exorbitant commissions by suppliers; misrepresentations by his book-keepers; and extortion. To avoid cash flow problems, Boyd even issued his own currency based upon wool, cattle, whale-oil, tallow, and hides. Workers spent these notes in the company stores. He was also covering up huge losses to his English shareholders in expectation of short- to medium-term revenues. His Royal Bank of Australia had raised money by issuing (unsecured) debentures. Boyd insisted that its directors should maintain utmost secrecy, thus setting the scene for a massive fraud against the debenture holders. The Bank with its proper sounding name was really a front designed for his own personal use.[7]

Four years later a visitor, speaking of the town, mentioned its Gothic church with a spire, commodious stores, well-built brick houses, and "a splendid hotel in the Elizabethan style". At this time Boyd had nine whalers working from this port.

Boyd was elected to the New South Wales Legislative Council for the Electoral district of Port Phillip in September 1844, a position he held for 11 months.[2]

Boyd and blackbirding[edit]

Boyd’s whaling and vast land holdings required huge numbers of workers. He advertised everywhere “To the labouring classes unemployed: Free passages to Twofold Bay and rations will be given for one hundred persons, consisting of shepherds, stockmen, shearers, artizans [sic], labourers . . .”[6] He had no shortage of volunteers to take his free passage, but the offer of an extra pound of wages from a rival sheep rancher always induced the new arrivals to break their engagement. Boyd ultimately resorted to employing convicts who had served their time, and learned to prefer them. But there were never enough workers.

Having difficulty in obtaining cheap labour, Boyd began blackbirding, or coercing people through deception and/or kidnapping. Typically, Boyd's men would lay anchor in a harbor and then beseech the local leader for fifty able-bodied men to clean the vessel. In another locale, they would invite some dozens aboard to trade tobacco, knives, files, matches and seamen’s clothing. The men aboard, he would then weigh anchor and kidnap the unsuspecting Islanders.

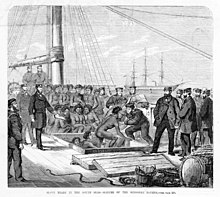

In 1847, Boyd brought the first 65 Islanders to Australia from Lifu Island in the Loyalty Islands (now part of New Caledonia) and from Tanna and Aneityum Islands in the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu). They landed at Boydtown. The clerk of the local bench of magistrates described them this way: “none of the natives could speak English, and all were naked..”. “[T]hey all crowded around us looking at us with the utmost surprize, and feeling at the Texture of our clothes…they seemed wild and restless." [8] They had all put their marks on contracts that bound them to work for five years and to be paid 26 shillings a year, plus rations of 10 lbs of meat a week, and two pairs of trousers, two shirts and a kilmarnock cap. However, clearly they had no idea of what they were doing in Australia, and the local magistrate refused to counter-sign the documents. Regardless, some of Boyd's employees began to take the party inland on foot. Some of them bolted and made their way back to Eden. The first one died on 2 May and as winter approached more became ill. Sixteen Lifu Islanders refused to work and began to try to walk back to Lifu along the coast. Some managed to reach Sydney and seven or eight entered a shop from the rear and began to help themselves to food. Those that remained at work were shepherds on far off Boyd stations on the Edward and Murray Rivers.

Boyd refused to admit that the trial shipment was a failure, sending for more Islanders. By this time colonial society was beginning to realise what he had done and was feeling uneasy. The New South Wales Legislative Council amended the Masters and Servants Act to ban importation of “the Natives of any Savage or uncivilized tribe inhabiting any Island or Country in the Pacific”. When Boyd's next group of 54 men and 3 women arrived in Sydney on 17 October, they could not be indentured and once Boyd found this out he refused to take any further responsibility. The same legal conditions also applied to Boyd's Islander labourers from the first trip; they left the stations and set off to walk to Sydney to find alternative work and to find a way home to the islands. The foreman tried to stop them but the local magistrate ruled that no one had the right to detain them. Their progress from the Riverina was followed by the press as they began their long march to Sydney. The press described them as cannibals on their way to eat Boyd, and the issue as depicted in the media was extremely racist.

The whole matter was raised again in the Legislative Council and Boyd showed no remorse or sense of responsibility. Boyd justified himself with reference to the African slave trade and there was much discussion in the colony about the issue to introducing slaves from the Pacific Islands. The recruiters were accused of kidnapping, a charge with they denied.

The Islanders remained around Sydney harbour, begging for transport back to their islands. Some of them found alternative work in Sydney and dropped out of the record. Most of the others finally embarked on a French ship returning to the islands, although it is unlikely that many of them ever reached their home islands. This fiasco was the first time Pacific Islanders had been imported into Australia as labourers, although some had already reached Sydney as ships' crews.

Boyd's troubles continued with the loss of two lawsuits for the insurance money on one of his vessels which was wrecked, but it seems his schemes were too grandiose for the then state of Australia. The shareholders in the Royal Bank became dissatisfied, and eventually all of the capital was lost and there was a deficiency of £80,000.

Boyd and the California Gold Rush[edit]

Boyd sailed away from his creditors in his yacht, the Wanderer, to California on 26 October 1849 to start a new venture when he heard about the California Gold Rush in 1849. He set off for San Francisco with a brigand of followers in his yacht Wanderer. Stopping in New Zealand, they loaded the ship with flour and Maori potatoes, which they sold at prodigious prices in the Golden Gate. Little is known of Boyd’s activities, but all his labours in the California foothills apparently came to naught. His heart was not in the panning for gold (fortunately he had a crew of kanaka sailors who did the digging for him). After the disappointment in the California gold fields, he shook off the dust and reviewed his options. He still had this glorious schooner and a sizeable amount of funds and investments.

Boyd and the Papuan Republic[edit]

With no success at the gold-diggings, in June 1851 Boyd sailed in the Wanderer among the Pacific islands with the aim of establishing a 'Papuan Republic or Confederation'.[1] Stopping first in Hawaii, Boyd convinced King Kamehameha to become regent of a Pacific empire ranging from Hawaii and the Marquesas to Samoa and Tonga, but his real plan was to loot them of their presumed resources.[9] He reconnoitred various South Seas islands and finally settled on two islands in the Solomons to base a South Seas republic. They were San Cristobal (now Makira) and Guadalcanal.

Boyd's death[edit]

Arriving from Hawaii, and presumably not knowing that Makira was the very harbor whence his ship Velocity, under different command, had kidnapped so many Islanders, Boyd lay at anchor for several days while he inspected ashore. On 15 October 1851, Boyd went ashore with a crew member to shoot game. Soon after entering a small creek in his boat, two shots were heard 15 minutes apart but Boyd never returned.[1] At the same time, the remaining crew aboard the Wanderer were involved in a large skirmish with the local population. Muskets, swivel guns and grapeshot were utilised against the natives resulting in over twenty-five fatalities.

A search party later looked for Boyd, finding a great number of foot imprints and evidence of a struggle, together with his boat, belt and an expended firearm cartridge . In days following Boyd's disappearance, his crew raided and destroyed a number of villages in the area now known as Wanderer Bay before sailing for Port Macquarie.[10]

Was entrepreneur Benjamin Boyd killed by the victims of his blackbirding expedition in Guadalcanal? The irony that the man who first brought indentured labour to Australia should finally be killed by those same islanders was not lost on his countrymen. As Mead quipped, “Australia’s penchant for cutting down tall poppies was never more dramatically gratified . . . That he had been eaten merely added titillation to a good story”.[11]

There were afterwards rumours that Boyd had survived and was living on Guadalcanal. At the end of 1854 an expedition led by Captain Lewis Truscott of the vessel Oberon was sent to the islands to make further enquiries. They found trees that Boyd had marked and so the searchers announced that they would give 100 tomahawks if Boyd was delivered to them alive. Two enterprising natives assured them that Boyd was dead and they presented what they claimed was Benjamin Boyd’s skull for “twenty tomahawks”. (Examining the skull, Australian phrenologists asserted that it was not Caucasian and the bone still resides in the Australian Museum in Sydney with the inscription “Skull of a Polynesian [sic—it was Melanesian] sent as Captain Boyd’s”.) Another Islander told the rescuers the probable truth that Boyd was “killed by Chief Possakow”. Unconvinced, the rescuers left behind hatchets, spectacles and cards with the inscription “Seeking you. Advise us. H.M.S Herald”. Nonetheless, the captain’s log concludes Boyd was killed after being captured.[12] This expedition was able to ascertain that Boyd was initially taken prisoner but was later executed in retribution for the number of villagers killed by the actions of the crew of the Wanderer. Boyd's head was cut off and his skull kept locally in a ceremonial house. Truscott was able to purchase Boyd's skull from the leading men of the district and returned with it to Sydney.[13]

Legacy[edit]

In 1971 the Ben Boyd National Park was established, located near Boydtown south of Eden and named after Boyd. The park area covers approximately 10,407 hectares (25,720 acres).

Boyd's Tower[14] is located at the entrance to the park near Twofold Bay and was designed as a lighthouse and lookout. The tower was designed by Oswald Brierly who had accompanied Boyd to Australia from England. It was built from sandstone quarried in Sydney.[15] The structure was not commissioned as a lighthouse and the building work stopped in 1847 as funds became short.[16] The tower was used as a whale sighting station.[17][18] Whaling was already an established industry when Boyd arrived in the area and he brought with him his own boats and crew,[19] aggressively went into competition with the locals and expanded his fleet until he had nine whaling boats working for him.[1]

Boyd's legacy includes the decaying buildings of Boydtown near Eden on Twofold Bay in New South Wales. The township was established by Boyd to provide services for the extensive properties he owned locally. It was abandoned in the mid-1840s when Boyd's finances failed.[19] The township has since been revived.

An addition, Ben Boyd Road in Neutral Bay, New South Wales was named in his honour; as was Boyd house of Neutral Bay Primary School.[20] A small plaque describing his life and death is on display at the corner of Ben Boyd Road and Kurraba Road, Neutral Bay.

To commemorate the 150th anniversary of Boyd's disappearance, a scale model of the Wanderer was created for the Eden Killer Whale Museum.[21]

Australian business schools still study the case of the "buccaneer entrepreneur" Benjamin Boyd in the contest of the history of rugged individualists and ethical conduct.[22]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Walsh, G P (1966). "Boyd, Benjamin (1801 - 1851)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. pp. 140–142. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: More than one of|accessdate=and|access-date=specified (help) - ^ a b c "Mr Benjamin Boyd (1803-1851)". Former members of the Parliament of New South Wales. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ "'Blackbirding' shame yet to be acknowledged in Australia". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney. 3 June 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ Sidney, Samuel (1852). The three colonies of Australia : New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia : their pastures, copper mines, & gold fields. Ingram, Cooke. ISBN 1-4374-4246-3.

- ^ Steven, Margaret. "Boyd, Benjamin". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3103. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Wellings, H.P.M. (1940). Benjamin Boyd in Australia (1842-1849) Shipping Magnate; Merchant; Banker; Pastoralist and Station Owner; Member of the Legislative Council; Town Planner; Whaler. State Library of Victoria: D S Ford. p. 29.

- ^ Holcomb, Janette (2014). Early merchant families of Sydney : speculation and risk management on the fringes of empire. London : Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1-78308-120-2.

- ^ Diamond, Marion. The Seahorse and the Wanderer. Ben Boyd in Australia (Melbourne 1988, pp 128-129

- ^ Webster, John (1858). The last cruise of "The Wanderer". Sydney : F. Cunninghame.

- ^ "THE LATE MR. BOYD AND THE SCHOONER "WANDERER."". The Argus (Melbourne). Vol. II, no. 990. Victoria, Australia. 31 December 1851. p. 2. Retrieved 29 June 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Mead, Tom (1980). Killers of Eden: the killer whales of Twofold Bay. London ; Sydney: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 978-0-207-14308-3.

- ^ Scott, Geoffrey (19 December 1953). "The mystery of a vanished adventurer". Sydney Morning Herald.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "THE LATE MR. BENJAMIN BOYD". The Sydney Morning Herald. Vol. XXXV, no. 5451. New South Wales, Australia. 4 December 1854. p. 5. Retrieved 29 June 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Searle, Garry. "Ben Boyd Tower". Lighthouses of New South Wales. SeaSide Lights. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- ^ "Ben Boyd National Park". NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service.

- ^ "Travel: Boydtown". The Sydney Morning Herald & The Age. 8 February 2004.

- ^ "Oswald W. B. Brierly - images from the exhibition Upon a painted ocean, 18 October to 6 February 2005: Whales in Sight. / A shore whaling party coming out of Twofold Bay, 1844 /watercolour drawing by Oswald W. Brierly". State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 17 September 2007. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- ^ "Ben Boyd National Park". New South Wales Government. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- ^ a b "Ben Boyd National Park = Culture and History". New South Wales Government. Archived from the original on 27 July 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- ^ "Sport houses". Neutral Bay Public School. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019.

- ^ Canberra Times, 23 July 2001, p. 5

- ^ Frederick, Howard; O'Connor, Allan; Kuratko, Donald F (2019). Entrepreneurship : theory/process/practice (5th Asia-Pacific ed.). South Melbourne, Vic. : Cengage Learning. pp. 97–100. ISBN 978-0-17-041175-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)

Further reading[edit]

- Plowman, Peter (2004). Ferry to Tasmania: A Short History. Rosenberg Publishing Pty, Limited. pp. 9–13. ISBN 1-877058-27-0.

- Diamond, Marion, (1988), The Seahorse and the Wanderer. Ben Boyd in Australia, Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0522843557

- "Travel - Boydtown". The Sydney Morning Herald & The Age. 8 February 2004.

- "Ben Boyd". ACT Government - Guidelines for Participating in the Cultural Map Project. Archived from the original on 31 August 2007. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- Loney, Jack (1985), Ben Boyd's Ships, Geelong, Neptune Press, 16p.

- Phillips, Valmai. 1977. Romance of Australian Lighthouses. Rigby, Adelaide. ISBN 0-7270-0498-0 pp. 45–47

- Alison Vincent (2008). "Boyd, Ben". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 8 October 2015. [CC-By-SA]

Category:1801 births

Category:1851 deaths

Category:Australian pastoralists

Category:Australian people of Scottish descent

Category:Missing people

Category:Australian stockbrokers

Category:Members of the New South Wales Legislative Council

Category:19th-century Australian politicians

Category:Australian whalers

Category:Australian ship owners

Category:19th-century Australian businesspeople

Category:Australian bankers

Category:Eden, New South Wales

Category:Settlers of Australia