User:Doppelklecks/History of Cologne

| “ | Fratres vos, qui legitis in istis voluminibus et invenietis ubi opus est ad emendandum, non maledictis sed cum omni diligentia emendetis. / You brothers who read in these pages and find that the work needs to be improved, do not curse it, but improve it with due diligence. (Monk, 11th century) | ” |

Cologne as Free Imperial City[edit]

Futile pacification efforts[edit]

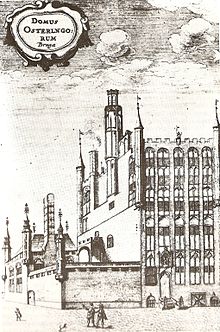

The economic region of the Spanish Netherlands, so foundational for Cologne's prosperity, did not come to rest in the 1570s. In 1575, the Spanish king Philipp II had to declare a state bankruptcy; the Spanish occupation troops of the Netherlands remained without pay. In 1576, they went marauding through Flanders and, looting, wreaked havoc in the city of Antwerp. This caused proverbial horror as the Spanish Fury and strengthened the resistance of the Flemings and Dutch against the Spanish crown. In the course of the riots, the newly built Hanseatic Kontor in Antwerp was also looted several times. The merchants of Cologne tried in vain to be compensated for the damage; in the following years, the Kontor lost its economic importance.[1]

The Union of Arras, agreed in January 1579 and followed promptly by the Union of Utrecht, marked the arising separation of the Spanish Netherlands, from which the states of the Netherlands and Belgium would ultimately emerge. The Union of Utrecht, dominated by the Province of Holland, was also joined by almost all the Brabant and Flanders cities. To pacify the disputes in the provinces, which formally still were part of the Holy Roman Empire, Emperor Rudolf II, the brother-in-law of the Spanish king, sought a negotiated settlement. The so-called Pacification Day took place in Cologne from April to November 1579, because the imperial city, as a strategically important metropolis, could be accepted as a neutral location and provide the necessary infrastructure for the delegations. The representatives of the Netherlands, the emperor and the Spanish crown were accommodated in the city palaces of Cologne's councillors. The negotiations themselves took place in the City hall called Gürzenich. However, the conferences ended without any agreement.[2] Today, Cologne's Pacification Day is understood as the starting point for the emergence of an independent Dutch state.[3] How vitally the Dutch disputes affected Cologne's interests got evidence in 1580, when Dutch warships came up the Rhine and advanced as far as Cologne. The coordinated efforts of a fleet of Rhenish electors promptly drove off the invaders.[4] Overall, developments were unfavorable to Cologne's economic interests. The unrest severely disrupted Cologne's trade routes to Flanders; in addition, the Dutch were able to control sea access to the Rhine. Both gravely impeded Cologne's trade flows and brought Cologne's trade with England to an almost complete standstill.[5]

Map leveraged city administration[edit]

The religious and economic unrest afflicting the Spanish Netherlands from 1566 onward was observed in Cologne with apprehensiveness.[6] The Spanish general Duke of Alba, sent to Brussels in 1567 as the new governor-general of the Spanish crown, sought to quell Flemish discontent with draconian measures and military force. Because of the tensions, many refugees left Antwerp and settled in Cologne; among the most illustrious were Jan Rubens, father of the subsequently famous painter Peter Paul, and Anna of Saxony, wife of William of Orange, who eventually became governor of the united Dutch provinces. Duke Alba therefore also exerted considerable pressure on the city of Cologne to keep refugees out of the Rhine city and to secure military transit routes to the Habsburg possessions in southern Europe.[7].

The Cologne Council endeavored to meet Spanish demands for improved city administration and a rigorous attitude toward refugees. To this end, as a modern administrative measure of the time, the council had a detailed Bird's-eye view of the city drawn up, to enhance the mastery of inhabitants and immigrants.[8] The cartographer Arnold Mercator drew up the plan at a scale of 1:2450, striving for a work that satisfied cartographic-scientific standards; the map was based on a comparatively accurate survey of the city's topography and showed the building tracts in the aim to create a spatial effect with a skillful mixture of elevation and bird's-eye view. Given its detailed and true-to-scale representation, the so-called Mercator Plan is considered today to be the first reliable city plan of Cologne[9] and is perceived as one of the first ever cartographically correct city maps.[10]

Printed in Cologne[edit]

The emerging technology of letterpress printing quickly was adopted in Cologne; as early as 1464, Ulrich Zell printed the first book. Untily the end of the 15th century, there was evidence of 20 printing works in Cologne, producing more than 1200 different editions. This made Cologne - after Venice, Paris and Rome - a leading book printing center in Europe.[11] For the families involved in the printing and publishing business, such as the Quentel, Birckmann and Gymnich, it was a prospering venture. Many of them expanded to other metropolises in Europe and formed cross-city cooperatives. Peter Quentel, the busiest in the new industry, was re-elected as a Cologne councilman for many years.[12] In 1524, Quentel published an edition in Low German language of Luther’s New Testament translation; from the late 1520s, however, the printing and distribution of Lutheran books was banned by the Cologne Council. Again, it was Peter Quentel who published the first complete German translation of the Bible by Johann Dietenberger (the so-called Dietenberger Bible), which was printed in Mainz in 1534 and eventually gained recognition as one of the Catholic correction Bibles.[13].

By developing into a leading publishing place for Latin-language works Cologne gained an exceptional position compared to all other book printing centers of the empire. The Cologne publishers aimed at nationwide distribution and unleashed a program including primarily religious, scientific, and humanistic works. For example, along with Basel, Cologne was the leading printing center to publish the writings of the humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam. Moreover, Cologne remained the only one of the major imperial cities to remain Catholic, and thus offered a comprehensive book program of counter-Reformation works that continued to argue in Latin.[14] The book that, from today's perspective, most prominently represents the Cologne printing industry, however, is the Koelhoff Chronicle with the title "Die Cronica van der hilliger Stat van Coellen" (Chronicle of the Holy City of Cologne): the work written in the Ripuarian dialect of Cologne region was published in 1499 by Johann Koelhoff the Younger. Today, it is considered the high point of late medieval Cologne city history.[15]

King's coronation in Frankfurt[edit]

Maximilian II got crowned German king in November 1562 in Frankfurt am Main - and not in Aachen, as generations of his ancestors. The ritualized procession that the coronator and king had celebrated since time immemorial from Aachen to Cologne to visit the shrine of the Three Kings was dispensed with. The king skipped the tradition, to pay homage to the Magi in Cologne. The coronation festivities, which for centuries had guaranteed Cologne a closeness to the imperial dominion and had given it a great character since 1484, were held in Frankfurt am Main. This Cologne setback resulted because Archbishop Frederick IV of Wied had not yet been papally confirmed at the time of the coronation; because of the autumn season, the great men of the Empire avoided the long journey from Frankfurt, where the election had taken place anyway, to Aachen and Cologne. In addition, the king sympathized with Protestant ideas and found relic homages out of date. All subsequent imperial coronations also took place in Frankfurt; as coronator henceforth celebrated the archbishop of Mainz.[16] Thus, this relocation detrimented the centuries-old narrative of the "Holy Cologne."[17] Not coincidentally, from 1567, Cologne councilors built a city hall loggia, which in its Renaissance style deliberately cited the triumphal arch architecture of Roman antiquity, thus recalling the historical greatness of Cologne.[18]

Efforts for the Cologne trade[edit]

In the 1550s, it became apparent that international trade was undergoing a fundamental change. Kontors based trade underpinned with trading privileges was losing cohesive strength; as overseas destinations were increasingly discovered, long-distance trade shifted away from the Rhine to the North Sea. Antwerp, which by 1560 had more than 100,000 inhabitants, emerged as the economic center of Europe and developed great commercial dynamism, displacing the Cologne merchants.[19] In southern Germany, the imperial cities of Augsburg and Nürnberg had also developed into important trading hubs; both cities had grown to over 30,000 inhabitants, almost the size of Cologne. This was also true for Magdeburg, which benefited from the staple rights on the Elbe.[20] The Cologne wholesalers, who dominated the city's council, therefore sought to strengthen Cologne's position in international trade. In 1553, the Cologne commodity exchange was founded inspired by Antwerp practice, which allowed the trading of commodity contracts. Additionally, the bill of exchange business became established when the Antwerp finance business partially shifted to Cologne.[21] In order to strengthen its traditional business branches - especially wine and cloth - Cologne became intensively involved in the Hanseatic League and in 1556 created the role of a syndic, a kind of secretary-general in an institution that until then had not known any representative.[22] The position was assigned to Heinrich Sudermann of Cologne, who was to use diplomatic means to prolong the old trading privileges. However, after Elizabeth I had taken up the government in England in 1558, it was not possible to make her endorse the continuation of the privileges for the Stalhof in London, whose importance therefore diminished over the years. After the relocation of the flanders Kontor to Antwerp and the construction of a respresentative trading post from 1563 to 1569, Sudermann struggled - ultimately in vain - to give the Kontor greater economic relevance.[23] More successful was the initiative of the Cologne Council to strengthen the trading business on the Rhine by building a new stacking house (Stapelhaus) (1558-1561). The building allowed, above all, to handle the fish trade more effectively; despite all international adversities, Cologne still benefited considerably from the Stapelrecht, that continued to remain in force.[24]

Renaissance in Cologne[edit]

In the 16th century, the patricians of Cologne began to reflect the Renaissance art trends they got to know on their trade journeys especially in Flanders, when commissioning works of art.[25] In 1517, the Cologne families Hackeney, Hardenrath, von Merle, von Straelen, Salm and von Berchem donated a rood screen for St. Maria im Kapitol; the elaborate work was ordered from an art carver in Mechelen, who thus made the Flemish Renaissance known in Cologne.[26] The town hall’s extension, called Löwenhof (Lion‘s Courtyard), was built in 1540 by Laurenz Cronenberg blending elements in late Gothic and Renaissance style. The Antwerp-born Cornelis Floris was commissioned by the cathedral chapter in 1561 to erect the epitaphs of the two archbishops from the house of Schaumburg, whose depiction gained proverbial recognition in Cologne as the Floris style.[27] Floris was also requested for the design of the town hall arbor, which was built from 1567; the construction, however, was assigned to the Cologne stonemason Wilhelm Vernukken.[28] The most sought-after Cologne Renaissance painter was Barthel Bruyn the Elder, who developed his own form for portrait paintings in Cologne.[29] Families who could afford it, however, had their members portrayed in London by the royal court painter Hans Holbein the Younger.[30]

-

Flemish: rood screen in St. Maria im Kapitol

-

Transitional style: Löwenhof in the City Hall

-

Floris style: epitaph in Cologne Cathedral

-

Triumphant arch style: City Hall Arbor

Trade routes to Flanders[edit]

For Cologne commerce, the trade route to Flanders and the North Sea was of foundational importance. In the 16th century, it needed to be realigned as trading flows shifted from Bruges to Antwerp, which emerged as the economic center of Europe in the mid-16th century.[31] By 1526, the city on the Scheldt was already larger than Cologne and had more than 50,000 inhabitants,[32] and by 1560 Antwerp had doubled its population.[33] In contrast, the importance of the Hanseatic Kontor of Bruges faded until the end of the 15th century, since Bruges could no longer be approached by seagoing ships due to the silting of the Zwin. Antwerp benefited from overseas trade flows; Portuguese merchants made the city a hub for long-distance import, for example to distribute sugar and pepper. Eventually, the Hanseatic League moved its Kontor to Antwerp in 1545 and had a prestigious new trading house built there by Cornelis Floris II from 1563 to 1569; however, it was only used to one-fifth of its capacity. Cologne merchants found it increasingly difficult to hold their own against international competition. To avoid confessional unrest in Antwerp, Portuguese, Italian as well as Flemish merchants settled directly in Cologne. They imported grain and furs, but above all cloth and silk fabrics, which put them in direct competition with Cologne's production. At times, the non-Cologne merchants bundled a third of Cologne's long-distance trade.[34].

References[edit]

- ^ Rhenish History: Heinrich Sudermann

- ^ Gérald Chaix: Cologne in the Age of Reformation and Catholic Reform 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, p. 243

- ^ Thomas P. Becker: Der Kölner Pazifikationskongress von 1579 und die Geburt der Niederlande, in: Michael Rohrschneider (ed.): Frühneuzeitliche Friedensstiftung in landesgeschichtlicher Perspektive, Cologne 2019, pp. 99-119, here p. 118

- ^ Gérald Chaix: Cologne in the Age of Reformation and Catholic Reform 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, p. 244

- ^ Christian Hillen, Peter Rothenhöfer, Ulrich Soénius: Kleine Illustrierte Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne 2013, p. 78

- ^ Gérald Chaix: Köln im Zeitalter von Reformation und Katholischer Reform 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, p. 242

- ^ Magnus Ressel: Der Herzog von Alba und die deutschen Städte im Westen des Reiches 1567–1573. Köln, Aachen und Trier im Vergleich; in: Andreas Rutz (ed.), Krieg und Kriegserfahrung im Westen des Reiches 1568-1714, Göttingen 2016, pp. 31-63, here p. 61

- ^ Gérald Chaix: Köln im Zeitalter von Reformation und Katholischer Reform 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, pp. 198f

- ^ Peter Noelke: Entdeckung der Geschichte, Arnold Mercators Stadtansicht von Köln. In: Renaissance am Rhein, Katalog zur Ausstellung im LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, 2010/2011, Munich 2010, p. 251

- ^ Stephan Hoppe: Die vermessene Stadt. Kleinräumige Vermessungskampagnen im Mitteleuropa des 16. Jahrhunderts und ihr funktionaler Kontext. In: Ingrid Baumgärtner (Ed.): Fürstliche Koordinaten. Landesvermessung und Herrschaftsvisualisierung um 1600, Leipzig 2014, p. 251–273, here p. 269

- ^ Wolfgang Schmitz: Eine Verlagsstadt von europäischem Rang: Köln im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert; in: Dagmar Täube, Miriam Fleck (eds.): Glanz und Größe des Mittelalters: Kölner Meisterwerke aus den großen Sammlungen der Welt, Cologne 2012, pp. 220-231, here p. 222

- ^ Wolfgang Schmitz: Die Überlieferung deutscher Texte im Kölner Buchdruck des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts. Habil.-Schrift Cologne 1990, p. 439

- ^ Gérald Chaix: Köln im Zeitalter von Reformation und Katholischer Reform 1512/13-1688, Cologne 2021, pp. 170, 172, 174

- ^ Gérald Chaix: Köln im Zeitalter von Reformation und Katholischer Reform 1512/13-1688, Cologne 2021, pp. 168, 175

- ^ Hans Lülfing (1980), "Koelhoff, Johann d. J.", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 12, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 319–319; (full text online)

- ^ Hansgeorg Molitor: Das Erzbistum Köln im Zeitalter der Glaubenskämpfe (1515-1688), (Geschichte des Erzbistums Köln Band 3), Cologne 2008, p. 181.

- ^ Rüdiger Marco Booz: Kölner Dom, die vollkommene Kathedrale, Petersberg 2022, p. 147.

- ^ Isabelle Kirgus: Die Rathauslaube in Köln 1569-1573, Architektur und Antikenrezeption, Bonn 2003.

- ^ Fernand Braudel: The perspective of the world, London 1984, p. 143

- ^ Christian Hillen, Peter Rothenhöfer, Ulrich Soénius: Kleine Illustrierte Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne 2013, p. 72

- ^ Christian Hillen, Peter Rothenhöfer, Ulrich Soénius: Kleine Illustrierte Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne 2013, p. 96

- ^ Gerald Chaix: Köln im Zeitalter der Reformation und katholischer Reform 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, p. 47ff

- ^ Rheinische Geschichte: Heinrich Sudermann

- ^ Christian Hillen, Peter Rothenhöfer, Ulrich Soénius: Kleine Illustrierte Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne 2013, pp. 80, 88

- ^ Isabelle Kirgus: Renaissance in Köln, Architektur und Ausstattung 1520-1620, Bonn 2004.

- ^ Thesy Teplitzky: Geld, Kunst, Macht: eine Kölner Familie zwischen Mittelalter und Renaissance. Cologne 2009, p. 106ff.

- ^ Rüdiger Marco Booz: Kölner Dom, die vollkommene Kathedrale, Petersberg 2022, p. 140.

- ^ Isabelle Kirgus: Die Rathauslaube in Köln 1569-1573, Architektur und Antikenrezeption, Bonn 2003.

- ^ Udo Mainzer: Kleine illustrierte Kunstgeschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne 2015, p. 93.

- ^ Miriam Verena Fleck: Köln - "... so berühmt und von so hohem Rufe, gewissermaßen einzigartig in deutschen Landen ..."; in: Dagmar Täube, Miriam Verena Fleck (eds.): Glanz und Größe des Mittelalters, Kölner Meisterwerke aus den großen Sammlungen der Welt, Munich 2011, pp. 20-36, here p. 29.

- ^ Fernand Braudel: The perspective of the world, London 1984, p. 143

- ^ Floris Prims: Antwerpen door de eeuwen heen, Antwerp 1951, p. 373

- ^ J.A. Houtte: Anvers aux XVe et XVIe siècles : expansion et apogée. In: Annales. Economies, sociétés, civilisations. 16e année, N. 2, 1961; pp. 248-278, here p. 249

- ^ Gerald Chaix: Köln in der Zeit von Reformation und katholischer Reform 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, p. 217ff