User:Delldot/Pb

| This is not a Wikipedia article: This is a workpage, a collection of material and work in progress that may or may not be incorporated into an article. It should not necessarily be considered factual or authoritative. |

(((*** TO DO ***)))

- Classification:

- S/S

- Exposure routes

- blinds, household products, fishing lures

- Pathophys

- Marks in img under neuro--turn yellow or something

- Dx

- Urine, serum

- Rx

- don't let them out until the house has been fixed

- Epidemiology

- Worldwide incidence

- Hx

- preindustrial vs. modern avg pb levels bar graph?

Classification[edit]

encephalopathy starting at 70 um/dl but usu 100.[1]

acute encephalop. at 150.[2] subacute or chronic more common than acute.[2]

description of early, late signs of lead encephalopathy.[3][9]

s/s show up at 40 but neurological damage may occur earlier and be missed.

Definition[edit]

Acute v chronic[edit]

Organic v inorganic[edit]

organic pb shows particular affinity for brain tissue.p.47

s/s[edit]

inorganic s/s per se.p.47

impaired vision.p.47

The delay between exposure and onset of symptoms varies widely depending partly on the individual and intensity and tempo of exposure.[4]

Lead is also toxic at levels below those that cause recognizable symptoms.[5]

wristdrop rare now.[2]

peripheral neuropathy rare in children but often in adults.[6]

encephalopathy sometimes starts abruptly p a latent period.[7]

anemia a late sign.p. 392

Acute v. Chronic[edit]

acute v. chronic[8]

Exposure routes[edit]

However, absorption in the lungs depends on the size of the particles inhaled.[9]

Small objects, e.g. paint chips or sip of ceramic glaze, may contain hundreds of milligrams of lead.[10]

Enviro[edit]

pb is a widespread environmental pollutant.

People who live in environments polluted by lead can experience elevated blood lead levels.[12]

Occupational exposure[edit]

whereas in the general population xposure is most oft thru ingestion, inhalation is more common in occupational setting.[13]

House dust[edit]

pb-containing paint particles are part of dust that gets on kids' hands, toys.[14]

Paint[edit]

pb still used in bridge, maritime paint.[15]

repeat opening , closing window common cause of paint -> dust.[15]

dust more common than pica as pb poisoning [per se] cause.[15]

children: Mouthing toys, consuming house dust, yard soil.[16]

in the US, 3/4 houses b4 '80 have pb paint inside.[15]

24 million homes (just US?) have pb paint.[17]

Water[edit]

pb poisoning has been caused by water wtih pb solder.[15]

products[edit]

in some develop. countries, eye shadow appl to infant boys, girls.[18]

Pathophys[edit]

kids have greater distribution of pb in soft tissues incl brain. [14]

In part because it can replace calcium ions in biological interactions, lead is able to pass through the protective blood-brain barrier which prevents many toxins from entering the brain.[19]

pb interferes with bone metabolism in bone and teeth and has been associated with cavities.[20]

pb acts on capillary endothelium in cns, causes glial proliferation, extravasation of plasma, other stuff.[21]

changes in cytoskeletal proteins[21]

inhibits ach release, increase dopamine norepi.[21]

Absorption[edit]

diarrhea discourages pb absorption, constipation increases it.[22] malnutrition + increased fat diet mb increase pb absorb.[15]

pb and ca++ compete for a single absorption channel.p.703

Excretion[edit]

0.5%/day from urine, independent of bll, 0.2%/d (each?) all other routes , ditto.[23]

Storage[edit]

released from bone faster in pregnancy, lactation, menopause, osteoporosis, immobilization, and hyperthyroidism; b/c increased bone turnover.[24]

95% pb stored in bone, 4% in brain liver kidneys, 1% in blood.[25]

pb substitutes for ca++ in hydroxyapetite in bone.[26]

pb accumulates where there are hi ca++ conc's and in tissues and organs w/highest mtmt activity.[9]

Over 99% of lead in the blood is bound to red blood cells.[26]

Enzymes[edit]

binds sulfhydryl, phosphate, carboxyl; thereby blocks enzymes, other macromlcls.[27]

Lead impairs a variety of enzyme systems and is toxic to those dependent on calcium and zinc.[2]

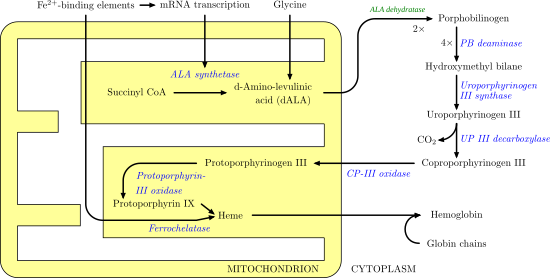

pb interferes with ALAD -> increased circulating ALA -> decrease in GABA release -> maybe why you see behavioral disorders.[28]

extensive discussion fo pb pathophys: fucks up cristae in mtmt, alters ca++ uptake into cells, strongly binds sulfhydryl groups on proteins, fucks up structural proteins, E metabolism, cell respiration, enhances spontaneous neurotrans release, inhibits stimulated release.[5] [10] </ref>

interferes with synaptogenesis in rat pups who drink pb-contaminated milk from mothers.[5]

Lead also causes red blood cells to become more fragile by interfering with another enzyme called pyrmidine-5'-nucleotidase.[29]

messes with nucleotide metabolism, bunch of other stuff.[27]

thyrroid fuckage.[30]

not known why pb causes cancer, but it does interfere with PKCs, wich increases DNA synth, which increases cell division + overgrowth, whcih may underlie carcinogenicity.p. 392

histology[edit]

pb forms complexes with acids in nuclei, appears to have a protective fx.p. 275

mtmt[edit]

pb damages mtmt and inhibits their fn.p. 275

Neuro[edit]

Lead colic, may be caused by lead's interference with normal nerve function of the gastrointestinal tract.[31]

pb interferes with myelin formation, messes wtih BBB integrity.[5]

pb interacts with mptp, causes mpt.[32]

messes up neurotrans--fucks with extracell ca++, so inhibits cholinergic ntnt .p. 392

pb also interferes with dopamine, aminobutyric acid.p. 392

prevents oligodendrocyte differentiation, which may be why such harmful developmental fx.p. 287

Infants and children[edit]

because of incomplete bbb, fetuses and children <36 mo brains and CNS most affected by pb exposure. [11]

children absorb pb more easily than adults.[25]

Complications[edit]

in children, changes in bone shape from pb.p. 392

decreased testicular function, incl decrease in circulating testosterone.p. 392

pb - > reduced growth in children.[33]

table of s/s at different levels - could make horizontal bar graph of s/s showing up after different levels.[34]

Cardiac[edit]

There may be a connection between low lead exposure and high blood pressure (possibly due to changes in kidney function), but this is controversial.[35]

Kidney[edit]

at pb conc's very hi, kidney dysfn impairs pb excretion mb.[23]

nephropathy at blls >60 ug/dl.[36]

Reproductive[edit]

child's IQ down for maternal bll up during pregnancy, delivery.[37]

Neuro[edit]

even 12 years later, pb in childhood correlated with school failure, reading impairment.[5]

correlation btw umbilical cord blood and neuro performance at age 2.[5]

decrease in iq and other cognitive abilities per pb exposure in children is even more pronounced at levels <10 ug/dl.[38]

IQ decreases apparently permanent.[39]

hearing loss prevents from learning speech in young child.[39]

Failure in school and reading problems have also been linked to lead exposure.[40]

Dx[edit]

neuropsych testing for cognitive dysfn.[17]

hair pb can show the time course of exposure but is not reliable b.c pb varies from hari to hair on one person.[21]p. 706 not really used though because not reliable.[17]

peripheral nerve conduction time, slowed in pb exposure can detect even subclinical pb increase.[21]706

BLL[edit]

One BLL measurement cannot distinguish between a high-level exposure over a short time and a low-level one over a chronic period.[41]

there's a risk of contamination of tubes w/pb used to collect blood samples.[13] Diagnosis from the Blood Smear NEJM Barbara J. Bain

bll may not be available immediately from the lab--sometimes chelation therapy is started before results are back.[42]

Blood from capillaries, e.g. from a finger prick, can be used to measure blood lead levels, but abnormal findings are usually rechecked with blood from veins due to the possibility of contamination of the capillary sample with tiny amounts of dust on skin.[39]

EP / ZPP[edit]

ARE YOU SURE EP AND ZPP ARE THE SAME THING? I.e. is there a zn in EP? [43] suggests yes.

prevention[edit]

CDC: "universal screening for children begin 6 mo."[8]

High dietary calcium impedes absorption of lead and is indicated for those who work in an environment that puts them at risk for lead exposure.[44] Adequate calcium intake has been recommended especially for children and pregnant and lactating women.[45]

Rx[edit]

chelating agents used for treatment of lead poisoning are edetate disodium calcium (CaNa2EDTA), dimercaprol (BAL), and succimer.[46][47]

4 chelating agents: dimercaprol (BAL) and edta are parenteral, d-penacillamine and succimer are oral.[21]706

Removal from lead workplace is part of mgmt of hi blls.[34]

adequate fluids are given to support kidney function, but not too much, which might exacerbate cerebral swelling.[42] pp. 1319-20

Ca-EDTA primary rx in humans and domestic animals.[48]

vit c may reduce pb toxicity.[49]

Children[edit]

children 10-20 ug/dL: rm source, nutritional evaluation, continued screening.[50] 20-44: maybe chelation, + enviro eval and remediation.[50]

Chelation[edit]

chelation recommended for children with >45 ug/dL bll.[51]

d-penacillamine side fx, less fxive.[10]

blls monitored before and during chelation to see if more needed, make sure it's working.[10]

Measurement[edit]

encephalopathy in adults usu occurs > 150 μg/dL, but 90-120 μg/dL can cause.[52] children can get it at >70-90 μg/dL.[52]

Prognosis[edit]

due to aggressive use of chelation therapy, mortality is low.[17]

in children, If symptoms of poisoning occur more than once, chances that effects will be permanent increase.[53]

hi mort rate pb encephalopathy. [12]

Epidemiology[edit]

img of seasonal trends [13] children's bll's peak in summer months, mb because more exposure to soil, or b/c windows.[14] But on the whole they're heading downward

avg pb intake per day is 5-15 ug/day, all ages.[54]

ca and fe deficiencies enhance pb absorpition esp in children.[3]

Genetic factors that may be involved in vulnerability to lead toxicity include polymorphisms for the vitamin D receptor and for proteins in red blood cells which bind lead, including amino levulinic acid dehydratase; however evidence for these predispositions is limited.[55]

hx[edit]

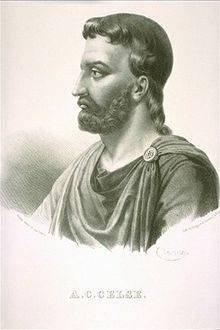

Aulus Cornelius Celsus, writing ca. A.D. 30, listed white lead on a list of poisons with antidotes, and claimed it could be remedied by mallow or walnut juice rubbed up in wine.[56][57][58]

20th century[edit]

at beginning of 2oth century a higher rate of pregnancy problems was noted in women who worked in or were married to someone who worked in the pottery industry.[59]

long-term neurological fx of pb poisoning noted 1st in 1943, followup of 'cured' pts.[60]

childhood pb poisoning was common in the US in the 50s and 60s, and that was when they established chelation \therapy.[59]

Blood lead levels have fallen sharply in countries that have eliminated leaded gasoline.[52]

Currently, mean blood lead levels for children and adults are about 2 µg/dL.[35] <-- worldwide or jsut us?

in 1960 CDC acceptable bll was 60 μg/dL.[61] has fig with declining levels.

EPA's phaseout of pb in gas 1973, done in 95.[60]

KXRF became avail in 1980s.[62]

image: graph of pre-industrial vs. modern pb levels. p. 861

In other animals[edit]

birds eat the lead shot pellets when they're eating stuff for their gizzards. bird img

pets get poisoned too, maybe worse. They're an indicator for concern in kids.

Not known how well birds of prey treated for pb poisoning reintegrate into their old lives in the wild.[48]

eating birds hunted with lead shot or eating the livers of birds with chronically elevated pb has been known to increase lead levels in hunters and their families.[63]

As with humans, chelation therapy is used to treat lead poisoning animals.[64]

Research directions[edit]

Vitamin C is not an FDA approved chelating agent and, as such, is not approved as a treatment for cases of lead poisoning in humans. However, an animal study of the efficacy of various chelating agents in treatment of acute lead poisoning showed that vitamin C (ascorbic acid), along with DMSA, CDTA and DMPS increased survival, while EGTA, N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) and various other agents did not.[65] Furthermore, in humans, high serum levels of vitamin C have been associated with a decreased prevalence of elevated blood lead levels[66] and intervention with supplemental vitamin C was shown to markedly decrease lead levels in smokers (mean: 81%). Authors hypothesize, however, that this effect might be due to an inhibition of lead absorption.[67]

Lead encephalopathy[edit]

enceph accompanied by neurodegeneration, necrosis of cortex, cerebral swelling.p. 392

Enceph may result in ment retardation, cerebral palsy, sz. p. 392

medical emergency and requires intensive supportive care.[46]

Lead encephalopathy more common in children.[8]

Used vcujs[edit]

White 07 ref name="Meyer-IntJHyge">Meyer, P. A.; Mcgeehin, M. A.; Falk, H. (Aug 2003). "A global approach to childhood lead poisoning prevention". International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 206 (4–5): 363–369. doi:10.1078/1438-4639-00232. ISSN 1438-4639. PMID 12971691. [15] </ref>

ref name="Guidotti07-PedClin"> name="Guidotti07-PedClin"</ref>

ref name="Woolf07-PedClin">Woolf, A.; Goldman, R.; Bellinger, D. (Apr 2007). "Update on the clinical management of childhood lead poisoning". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 54 (2): 271–294, viii. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2007.01.008. ISSN 0031-3955. PMID 17448360. Woolf</ref>

ref name="Needleman09-AnnEP">Needleman, H. (2009). "Low level lead exposure: history and discovery". Annals of Epidemiology. 19 (4): 235–238. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.01.022. PMID 19344860.</ref> [16]

References[edit]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Cecil08was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

Dart041426was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Casarett, Klaassen, Doull (2007) pp. 944

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Kosnett05-825was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f Needleman, H. (2004). "Lead poisoning". Annual Review of Medicine. 55: 209–222. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.103653. PMID 14746518.

- ^ Osterhoudt, K.C.; Ewald, M.B.; Shannon, M.; Henretig, F.M. (2006). "Toxicologic emergencies". In Fleisher, G.R.; Ludwig, S.; Henretig, F.M. (ed.). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Volume 355, 5th edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 983. ISBN 0781750741.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Kosnett05-830was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Brunton (2007) pp. 1131

- ^ a b Grant (2009) pp. 771

- ^ a b c Kosnett (2006) pp.241 [1] Cite error: The named reference "Kosnett06-241" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Watts, J. (2009). "Lead poisoning cases spark riots in China". Lancet. 374 (9693): 868–812. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61612-3. PMID 19757511. S2CID 28603179. [2]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Mañay08was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Brodkin, E.; Copes, R.; Mattman, A.; Kennedy, J.; Kling, R.; Yassi, A. (Jan 2007). "Lead and mercury exposures: interpretation and action" (Free full text). Canadian Medical Association Journal. 176 (1): 59–63. doi:10.1503/cmaj.060790. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 1764574. PMID 17200393.

- ^ a b [3] p.983

- ^ a b c d e f Rudolph, C.D., ed. (2003). Rudolph's Pediatrics, 21st edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0838582850. p.368

- ^ Kosnett (2006) pp.237

- ^ a b c d e Ragan, P.; Turner, T. (2009). "Working to prevent lead poisoning in children: getting the lead out". JAAPA : Official Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 22 (7): 40–45. doi:10.1097/01720610-200907000-00010. PMID 19697571. S2CID 41456653.[4]

- ^ # (2007) pp. [5]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Sanders09was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Casarett07-946was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f # (2007) pp. p.705

- ^ # (2007) pp. [6]

- ^ a b Grant (2009) pp. 773

- ^ Vaziri, N. D. (Aug 2008). "Mechanisms of lead-induced hypertension and cardiovascular disease" (Free full text). American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 295 (2): H454–H465. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00158.2008. ISSN 0363-6135. PMC 2519216. PMID 18567711.

- ^ a b Pearce 07

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Hu07was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Kosnett (2006) pp.238 [7] Cite error: The named reference "Kosnett06-238" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Patrick06was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Mycyk05-462was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^

- Chisolm, J.J. (2004). "Lead poisoning". In Crocetti, M.; Barone, M.A.; Oski, F.A. (ed.). Oski's Essential Pediatrics, 2nd edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0781737702.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

- Chisolm, J.J. (2004). "Lead poisoning". In Crocetti, M.; Barone, M.A.; Oski, F.A. (ed.). Oski's Essential Pediatrics, 2nd edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0781737702.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Rubin08-267was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ #CITEREFKosnett05 (2005) pp. 822

- ^ Murata K, I. T.; Iwata, Toyoto; Dakeishi, Miwako; Karita, Kanae (2009). "Lead toxicity: does the critical level of lead resulting in adverse effects differ between adults and children?" (Free full text (PDF)). Journal of Occupational Health. 51 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1539/joh.K8003. ISSN 1341-9145. PMID 18987427. S2CID 27759109.

- ^ a b Kosnett, J.; Wedeen, P.; Rothenberg, J.; Hipkins, L.; Materna, L.; Schwartz, S.; Hu, H.; Woolf, A. (Mar 2007). "Recommendations for Medical Management of Adult Lead Exposure". Environmental Health Perspectives. 115 (3): 463–471. doi:10.1289/ehp.9784. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 1849937. PMID 17431500.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Rossi09was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Grant (2009) pp. 789

- ^ Bradberry, S.; Vale, A. (2009). "Dimercaptosuccinic acid (succimer; DMSA) in inorganic lead poisoning". Clinical Toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.). 47 (7): 617–631. doi:10.1080/15563650903174828. PMID 19663612. S2CID 42138258. [8]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Cleveland08was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Pearson, Schonfeld (2003) pp.369

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lanphear05EnvironHealthwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Barbosawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Henretig061316was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Grant (2009) pp. 784

- ^ Trevor, Katzung, Masters (2007) pp. 480

- ^ Kalia, K.; Flora, S. J. (2005). "Strategies for safe and effective therapeutic measures for chronic arsenic and lead poisoning". Journal of Occupational Health. 47 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1539/joh.47.1. PMID 15703449. S2CID 6840312.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Katzung07-948was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Pearson03-370was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Redig, P.; Arent, L. (May 2008). "Raptor toxicology". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice. 11 (2): 261–282, vi. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2007.12.004. ISSN 1094-9194. PMID 18406387.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Yu05-193was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Mycyk05-465was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Merrill, JC; Morton, JJP; Soileau, SD (2007) p. 862

- ^ a b c Karri, S. S.; Saper, R.; Kales, S. (Jan 2008). "Lead Encephalopathy Due to Traditional Medicines". Current Drug Safety. 3 (1): 54–59. doi:10.2174/157488608783333907. ISSN 1574-8863. PMC 2538609. PMID 18690981.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Chisolm04-223was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Dart, RC; Hurlbut, KM; Boyer-Hassen, LV (2004) pp. 1423

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Bellinger04-Pediwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Celsus, de Medicina, V.27.12b

- ^ Ali, Esmat A. (1993). "Damage to plants due to industrial pollution and their use as bioindicators in Egypt". Environmental Pollution. 81 (3): 251–255. doi:10.1016/0269-7491(93)90207-5. PMID 15091810.

- ^ Marmiroli, Marta; Antonioli, Gianni; Maestri, Elena; Marmiroli, Nelson (March 2005). "Evidence of the involvement of plant ligno-cellulosic structure in the sequestration of Pb: an X-ray spectroscopy-based analysis". Environmental Pollution. 134 (2): 217–227. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2004.08.004. PMID 15589649.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Henretig FM (2006). "Lead". In Goldfrank, LR (ed.). Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies, 8th edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 1310. ISBN 0071437630.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Merrill07was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gilbert, G.; Weiss, B. (Sep 2006). "A rationale for lowering the blood lead action level from 10 to 2 μg/dL". Neurotoxicology. 27 (5): 693–701. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2006.06.008. ISSN 0161-813X. PMC 2212280. PMID 16889836.

- ^ Shih, A.; Hu, H.; Weisskopf, G.; Schwartz, S. (Mar 2007). "Cumulative Lead Dose and Cognitive Function in Adults: A Review of Studies That Measured Both Blood Lead and Bone Lead". Environmental Health Perspectives. 115 (3): 483–492. doi:10.1289/ehp.9786. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 1849945. PMID 17431502.

- ^ Pokras ecohealth

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lightfoot08-VetClinwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Llobet, J. M.; Domingo, J. L.; Paternain, J. L.; Corbella, J. (1990). "Treatment of acute lead intoxication. A quantitative comparison of a number of chelating agents". Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 19 (2): 185–189. doi:10.1007/BF01056085. PMID 2322019. S2CID 41820004.

- ^ Simon JA, Hudes ES (1999). "Relationship of ascorbic acid to blood lead levels". JAMA. 281 (24): 2289–93. doi:10.1001/jama.281.24.2289. PMID 10386552. S2CID 43839184.

- ^ Dawson E, Evans D, Harris W, Teter M, McGanity W (1999). "The effect of ascorbic acid supplementation on the blood lead levels of smokers". J Am Coll Nutr. 18 (2): 166–70. doi:10.1080/07315724.1999.10718845. PMID 10204833.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Masters, R.; Coplan, M. (1999). "Water treatment with silicofluorides and lead toxicity". International Journal of Environmental Studies. 56 (4): 435. doi:10.1080/00207239908711215.