User:DecafPotato/sandbox/5

History[edit]

Indigenous peoples and European colonization[edit]

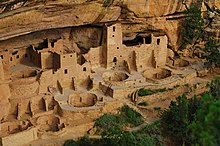

The first inhabitants of North America migrated from Siberia across the Bering land bridge at least 12,000 years ago;[1][2] the Clovis culture, which appeared around 11,000 BC, is believed to be the first widespread culture in the Americas.[3][4] Over time, indigenous North American culutures grew increasingly sophisticated, and some, such as the Mississippian culture, developed agriculture, architecture, and complex societies.[5] Indigenous peoples and cultures such as the Algonquian peoples,[6] Ancestral Puebloans,[7] and the Iroquois developed across the present-day United States.[8] Native population estimates of what is now the United States before the arrival of European immigrants range from around 500,000[9][10] to nearly 10 million.[10][11]

Christopher Columbus began exlporing the Caribbean in 1492, leading to Spanish settlements in Florida and New Mexico.[12][13][14] France established their own settlements along the Missisippi River and Gulf of Mexico.[15] British colonization of the East Coast began with the Virginia Colony (1607) and Plymouth Colony (1620).[16][17] The Mayflower Compact and the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut established precedents for representative self-governance and constitutionalism that would develop throughout the American colonies.[18][19] While European settlers experienced conflicts with Native Americans, they also engaged in trade, exchanging European tools for food and animal pelts.[20] The native population of America declined after European arrival,[21][22][23] primarily as a result of infectious diseases brought from Europe such as smallpox and measles,[24][25] and native peoples were displaced by European expansion.[26] Colonial authories pursued policies to force Native Americans to adopt European lifestyles,[27][28] and European settlers trafficked African slaves into the colonial United States through the Atlantic slave trade.[29] The original Thirteen Colonies[a] were administered by Great Britain,[30] all of which had local governments with elections open to most white male property owners.[31][32] The colonial population grew rapidly, eclipsing Native American populations;[33] by the 1770s, the natural increase of the population was such that only a small minority of Americans had been born overseas.[34] The colonies' distance from Britain allowed for the development of self-governance,[35] and the First Great Awakening—a series of Christian revivals—fueled colonial interest in religious liberty.[36]

Revolution and expansion[edit]

After winning the French and Indian War, Britain began to assert greater control over local colonial affairs, creating colonial political resistance; one of the primary colonial grievances was that Britain taxed the colonies without giving them representation in government. In 1774, the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia, and passed a colonial boycott of British goods. The British attempt to disarm the colonists resulted in the 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord, igniting the American Revolutionary War. At the Second Continental Congress, the colonies appointed George Washington commander-in-chief of the Continental Army and created a committee led by Thomas Jefferson to write the Declaration of Independence, adopted on July 4, 1776.[37]

After British surrender at the siege of Yorktown in 1781, Britain signed a peace treaty. American sovereignty became internationally recognized, and the U.S. gained territory east of the Mississippi River from present-day Canada in the north to Florida in the south.[38] Ratified in 1781, the Articles of Confederation established a decentralized government that operated until 1789.[37] The Northwest Ordinance (1787) established the precedent by which the national government would be sovereign and expand with the admission of new states.[39] The U.S. Constitution was drafted at the 1787 Constitutional Convention; it went into effect in 1789, creating a federation administered by three branches on the principle of checks and balances. Washington was elected the nation's first president under the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights was adopted in 1791 to allay concerns by sceptics of the more centralized government.[40][41]

In the late 18th century, American settlers began to expand westward, with a sense of manifest destiny.[42] The Louisiana Purchase (1803) from France nearly doubled the territory of the United States.[43] Lingering issues with Britain remained, leading to the War of 1812, which was fought to a draw.[44] Spain ceded Florida and their Gulf Coast territory in 1819.[45] As Americans expanded further into land inhabited by Native Americans, the federal government often applied policies of Indian removal or assimilation.[46][47] The displacement prompted a long series of American Indian Wars west of the Mississippi River.[48][49] The Republic of Texas was annexed in 1845,[50] and the 1846 Oregon Treaty led to U.S. control of the present-day American Northwest.[51] Victory in the Mexican–American War resulted in the 1848 Mexican Cession of California and much of the present-day American Southwest, resulting in the U.S. stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans.[42][52] Alaska was purchased from Russia in 1867.[53] Pro-American elements in Hawaii overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy; the islands were annexed in 1898. Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines were ceded by Spain following the Spanish–American War.[54] American Samoa was acquired by the United States in 1900 after the Second Samoan Civil War.[55] The U.S. Virgin Islands were purchased from Denmark in 1917.[56]

During the colonial period, slavery was legal in the American colonies, though the practice began to be questioned during the American Revolution.[57] Slavery was abolished in northern states,[58] though support for slavery remained in the South.[59][60][61] The sectional conflict regarding slavery culminated in the American Civil War (1861–1865).[62][63] Eleven slave states seceded and formed the Confederate States of America, while the remaining states formed the Union.[64] War broke out in April 1861 after the Confederacy bombarded Fort Sumter;[65] the war began to turn in the Union's favor following the 1863 Siege of Vicksburg and Battle of Gettysburg, and the Confederacy surrendered in 1865 after the Union's victory in the Battle of Appomattox Court House.[66] The Reconstruction era followed the war. After the assasination of President Abraham Lincoln, Reconstruction Amendments were passed to protect the rights of African Americans. National infastructure, including transcontinental telegraph and railroads, spurred growth in the American frontier.[67]

Contemporary United States[edit]

From 1865 through 1918 an unprecedented stream of immigrants arrived in the United States, including 24.4 million from Europe.[68] Most came through the port of New York City, and New York and other large cities on the East Coast became home to large Jewish, Irish, and Italian populations, while many Germans and Central Europeans moved to the Midwest. At the same time, about one million French Canadians migrated from Quebec to New England.[69] During the Great Migration, millions of African Americans left the rural South for urban areas in the North.[70] The Compromise of 1877 effectively ended Reconstruction and white supremacists took local control of Southern politics.[71][72] African Americans endured a period of heightened, overt racism following Reconstruction, a time often called the nadir of American race relations.[73] From 1890 to 1910, southern states established Jim Crow laws, disenfranchising African Americans. Racial segregation was prevalent nationwide and discrimination was codified, especially in the South.[74] Rapid economic development during the late 19th and early 20th centuries fostered the rise of many prominent industrialists, largely by their formation of trusts and monopolies to prevent competition.[75] Tycoons led the nation's expansion in the railroad, petroleum, and steel industries. Banking became a major part of the economy, and the United States emerged as a pioneer of the automotive industry.[76] These changes were accompanied by significant increases in economic inequality, slum conditions, and social unrest.[77][78][79] This period eventually ended with the advent of the Progressive Era, which was characterized by significant reforms.[80]

The early 20th century was a time of industrial expansion and social change in the United States.[81][82] The United States entered World War I alongside the Allies of World War I, helping to turn the tide against the Central Powers.[83] In 1920, a constitutional amendment granted nationwide women's suffrage.[84] During the 1920s and 1930s, radio for mass communication and the invention of early television transformed communications nationwide.[85] The Wall Street Crash of 1929 triggered the Great Depression, which President Franklin D. Roosevelt responded to with New Deal social and economic policies.[86][87] At first neutral during World War II, the U.S. began supplying war materiel to the Allies of World War II in March 1941 and entered the war in December after the Empire of Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor.[88][89] The U.S. developed the first nuclear weapons and used them again the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, ending the war.[90][91] The United States was one of the "Four Policemen" who met to plan the postwar world, alongside the United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and China.[92][93] The U.S. emerged relatively unscathed from the war, with even greater economic and military influence.[94]

After World War II, the United States entered the Cold War, where geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union led the two countries to dominate world affairs.[95] The U.S. engaged in regime change against governments perceived to be aligned with the Soviet Union, and competed in the Space Race, culminating in the first crewed Moon landing in 1969.[96][97][98][99] Domestically, the U.S. experienced economic growth, urbanization, and population growth following World War II.[100] The civil rights movement emerged, with Martin Luther King Jr. becoming a prominent leader in the early 1960s.[101] The counterculture movement in the U.S. brought significant social changes, including the liberalization of attitudes towards recreational drug use and sexuality[102][103] as well as open defiance of the military draft and opposition to intervention in Vietnam.[104] The late 1980s and early 1990s saw the collapse of the Warsaw Pact and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which marked the end of the Cold War and solidified the U.S. as the world's sole superpower.[105][106][107][108]

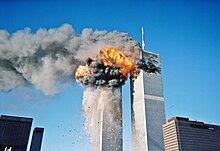

In the early 21st century, the September 11 attacks in 2001 led to the war on terror and military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq.[109][110] The U.S. housing bubble in 2006 culminated in the 2007–2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession, the largest economic contraction since the Great Depression.[111] Amid the financial crisis, Barack Obama, the first multiracial president, was elected in 2008.[112][113] Starting in the 2010s, political polarization increased as sociopolitical debates on cultural issues dominated political discussion.[114]

References[edit]

- ^ Erlandson, Rick & Vellanoweth 2008, p. 19.

- ^ Savage 2011, p. 55.

- ^ Waters & Stafford 2007, pp. 1122–1126.

- ^ Flannery 2015, pp. 173–185.

- ^ Lockard 2010, p. 315.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution—Handbook of North American Indians series: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15—Northeast. Bruce G. Trigger (volume editor). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. 1978 References to Indian burning for the Eastern Algonquians, Virginia Algonquians, Northern Iroquois, Huron, Mahican, and Delaware Tribes and peoples.

- ^ Fagan 2016, p. 390.

- ^ Snow, Dean R. (1994). The Iroquois. Blackwell Publishers, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-55786-938-8. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

- ^ Thornton 1998, p. 34.

- ^ a b Perdue & Green 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Haines, Haines & Steckel 2000, p. 12.

- ^ Davis, Frederick T. (1932). "The Record of Ponce de Leon's Discovery of Florida, 1513". The QUARTERLY Periodical of THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY. XI (1): 5–6.

- ^ Florida Center for Instructional Technology (2002). "Pedro Menendez de Aviles Claims Florida for Spain". A Short History of Florida. University of South Florida.

- ^ "Not So Fast, Jamestown: St. Augustine Was Here First". NPR. February 28, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ Petto, Christine Marie (2007). When France Was King of Cartography: The Patronage and Production of Maps in Early Modern France. Lexington Books. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-7391-6247-7.

- ^ Seelye, James E. Jr.; Selby, Shawn (2018). Shaping North America: From Exploration to the American Revolution [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 344. ISBN 978-1-4408-3669-5.

- ^ Bellah, Robert Neelly; Madsen, Richard; Sullivan, William M.; Swidler, Ann; Tipton, Steven M. (1985). Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life. University of California Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-520-05388-5. OL 7708974M.

- ^ Remini 2007, pp. 2–3

- ^ Johnson 1997, pp. 26–30

- ^ Ripper, 2008 p. 6

- ^ Cook, Noble (1998). Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62730-6.

- ^ Treuer, David. "The new book 'The Other Slavery' will make you rethink American history". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ^ Stannard, 1993 p. xii

- ^ "The Cambridge encyclopedia of human paleopathology Archived February 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine". Arthur C. Aufderheide, Conrado Rodríguez-Martín, Odin Langsjoen (1998). Cambridge University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-521-55203-5

- ^ Bianchine, Russo, 1992 pp. 225–232

- ^ Joseph 2016, p. 590.

- ^ Ripper, 2008 p. 5

- ^ Calloway, 1998, p. 55

- ^ Thomas, Hugh (1997). The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440–1870. Simon and Schuster. pp. 516. ISBN 0-684-83565-7.

- ^ Bilhartz, Terry D.; Elliott, Alan C. (2007). Currents in American History: A Brief History of the United States. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1817-7.

- ^ Wood, Gordon S. (1998). The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787. UNC Press Books. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-8078-4723-7.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Donald (2013). "The Right to Vote and the Rise of Democracy, 1787–1828". Journal of the Early Republic. 33 (2): 220. doi:10.1353/jer.2013.0033. S2CID 145135025.

- ^ Walton, 2009, pp. 38–39

- ^ Walton, 2009, p. 35

- ^ Otis, James (1763). The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved. ISBN 978-0-665-52678-7.

- ^ Foner, Eric (1998). The Story of American Freedom (1st ed.). W.W. Norton. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-393-04665-6.

story of American freedom.

- ^ a b Fabian Young, Alfred; Nash, Gary B.; Raphael, Ray (2011). Revolutionary Founders: Rebels, Radicals, and Reformers in the Making of the Nation. Random House Digital. pp. 4–7. ISBN 978-0-307-27110-5.

- ^ Miller, Hunter (ed.). "British-American Diplomacy: The Paris Peace Treaty of September 30, 1783". The Avalon Project at Yale Law School.

- ^ Shōsuke Satō, History of the land question in the United States, Johns Hopkins University, (1886), p. 352

- ^ Boyer, 2007, pp. 192–193

- ^ "Bill of Rights – Facts & Summary". History.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2015.

- ^ a b Carlisle, Rodney P.; Golson, J. Geoffrey (2007). Manifest destiny and the expansion of America. Turning Points in History Series. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-85109-834-7. OCLC 659807062.

- ^ "Louisiana Purchase" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ Wait, Eugene M. (1999). America and the War of 1812. Nova Publishers. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-56072-644-9.

- ^ Klose, Nelson; Jones, Robert F. (1994). United States History to 1877. Barron's Educational Series. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-8120-1834-9.

- ^ Frymer, Paul (2017). Building an American empire : the era of territorial and political expansion. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-8535-0. OCLC 981954623.

- ^ Calloway, Colin G. (2019). First peoples : a documentary survey of American Indian history (6th ed.). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, Macmillan Learning. ISBN 978-1-319-10491-7. OCLC 1035393060.

- ^ Michno, Gregory (2003). Encyclopedia of Indian Wars: Western Battles and Skirmishes, 1850–1890. Mountain Press Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87842-468-9.

- ^ Billington, Ray Allen; Ridge, Martin (2001). Westward Expansion: A History of the American Frontier. UNM Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8263-1981-4.

- ^ Morrison, Michael A. (April 28, 1997). Slavery and the American West: The Eclipse of Manifest Destiny and the Coming of the Civil War. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 13–21. ISBN 978-0-8078-4796-1.

- ^ Kemp, Roger L. (2010). Documents of American Democracy: A Collection of Essential Works. McFarland. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-7864-4210-2. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ McIlwraith, Thomas F.; Muller, Edward K. (2001). North America: The Historical Geography of a Changing Continent. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7425-0019-8. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ "Purchase of Alaska, 1867". Office of the Historian. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ "The Spanish–American War, 1898". Office of the Historian. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ Ryden, George Herbert. The Foreign Policy of the United States in Relation to Samoa. New York: Octagon Books, 1975.

- ^ "Virgin Islands History". Vinow.com. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Walker Howe 2007, p. 52–54; Wright 2022.

- ^ Walker Howe 2007, p. 52–54; Rodriguez 2015, p. XXXIV; Wright 2022.

- ^ Walton, 2009, p. 43

- ^ Gordon, 2004, pp. 27,29

- ^ Walker Howe 2007, p. 478, 481–482, 587–588.

- ^ Murray, Stuart (2004). Atlas of American Military History. Infobase Publishing. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-4381-3025-5. Retrieved October 25, 2015. Lewis, Harold T. (2001). Christian Social Witness. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-56101-188-9.

- ^ Woods, Michael E. (2012). "What Twenty-First-Century Historians Have Said about the Causes of Disunion: A Civil War Sesquicentennial Review of the Recent Literature". The Journal of American History. 99 (2). [Oxford University Press, Organization of American Historians]: 415–439. doi:10.1093/jahist/jas272. ISSN 0021-8723. JSTOR 44306803. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ Silkenat, D. (2019). Raising the White Flag: How Surrender Defined the American Civil War. Civil War America. University of North Carolina Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4696-4973-3. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ Vinovskis, Maris (1990). Toward A Social History of the American Civil War: Exploratory Essays. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-521-39559-5.

- ^ Davis, Jefferson. A Short History of the Confederate States of America, 1890, 2010. ISBN 978-1-175-82358-8. Available free online as an ebook. Chapter LXXXVIII, "Re-establishment of the Union by force", p. 503. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ Black, Jeremy (2011). Fighting for America: The Struggle for Mastery in North America, 1519–1871. Indiana University Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-253-35660-4.

- ^ U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States (1976) series C89-C119, pp 105–9

- ^ Stephan Thernstrom, ed., Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (1980) covers the history of all the main groups

- ^ "The Great Migration (1910–1970)". National Archives. May 20, 2021.

- ^ Woodward, C. Vann (1991). Reunion and Reaction: The Compromise of 1877 and the End of Reconstruction. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Drew Gilpin Faust; Eric Foner; Clarence E. Walker. "White Southern Responses to Black Emancipation". American Experience.

- ^ Trelease, Allen W. (1979). White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-313-21168-X.

- ^ Shearer Davis Bowman (1993). Masters and Lords: Mid-19th-Century U.S. Planters and Prussian Junkers. Oxford UP. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-19-536394-4.

- ^ Dole, Charles F. (1907). "The Ethics of Speculation". The Atlantic Monthly. C (December 1907): 812–818.

- ^ The Pit Boss (February 26, 2021). "The Pit Stop: The American Automotive Industry Is Packed With History". Rumble On. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ Tindall, George Brown and Shi, David E. (2012). America: A Narrative History (Brief Ninth Edition) (Vol. 2). W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-91267-8 p. 589

- ^ Zinn, 2005, pp. 321–357

- ^ Fraser, Steve (2015). The Age of Acquiescence: The Life and Death of American Resistance to Organized Wealth and Power. Little, Brown and Company. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-316-18543-1.

- ^ Aldrich, Mark. Safety First: Technology, Labor and Business in the Building of Work Safety, 1870-1939. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8018-5405-9

- ^ Hirschman, Charles; Mogford, Elizabeth (1 December 2009). "Immigration and the American Industrial Revolution From 1880 to 1920". Social Science Research. 38 (4): 897–920. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.04.001. ISSN 0049-089X. PMC 2760060. PMID 20160966.

- ^ "Progressive Era to New Era, 1900-1929 | U.S. History Primary Source Timeline | Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ McDuffie, Jerome; Piggrem, Gary Wayne; Woodworth, Steven E. (2005). U.S. History Super Review. Piscataway, NJ: Research & Education Association. p. 418. ISBN 978-0-7386-0070-3.

- ^ Larson, Elizabeth C.; Meltvedt, Kristi R. (2021). "Women's suffrage: fact sheet". CRS Reports (Library of Congress. Congressional Research Service). Report / Congressional Research Service. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ Winchester 2013, pp. 410–411.

- ^ Axinn, June; Stern, Mark J. (2007). Social Welfare: A History of the American Response to Need (7th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-52215-6.

- ^ James Noble Gregory (1991). American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507136-8. Retrieved October 25, 2015. "Mass Exodus From the Plains". American Experience. WGBH Educational Foundation. 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2014. Fanslow, Robin A. (April 6, 1997). "The Migrant Experience". American Folklore Center. Library of Congress. Retrieved October 5, 2014. Stein, Walter J. (1973). California and the Dust Bowl Migration. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-6267-6. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ The official WRA record from 1946 states that it was 120,000 people. See War Relocation Authority (1946). The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Study. p. 8. This number does not include people held in other camps such as those run by the DoJ or U.S. Army. Other sources may give numbers slightly more or less than 120,000.

- ^ Yamasaki, Mitch. "Pearl Harbor and America's Entry into World War II: A Documentary History" (PDF). World War II Internment in Hawaii. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "Why did Japan surrender in World War II?". The Japan Times. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ Pacific War Research Society (2006). Japan's Longest Day. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-4-7700-2887-7.

- ^ Hoopes & Brinkley 1997, p. 100.

- ^ Gaddis 1972, p. 25.

- ^ Kennedy, Paul (1989). The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. New York: Vintage. p. 358. ISBN 978-0-679-72019-5

- ^ Sempa, Francis (12 July 2017). Geopolitics: From the Cold War to the 21st Century. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-51768-3.

- ^ Blakemore, Erin (March 22, 2019). "What was the Cold War?". National Geographic. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ Mark Kramer, "The Soviet Bloc and the Cold War in Europe," in Larresm, Klaus, ed. (2014). A Companion to Europe Since 1945. Wiley. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-118-89024-0.

- ^ Blakeley, 2009, p. 92

- ^ Collins, Michael (1988). Liftoff: The Story of America's Adventure in Space. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1011-4.

- ^ Winchester 2013, pp. 305–308.

- ^ "The Civil Rights Movement". PBS.org. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ Svetlana Ter-Grigoryan (February 12, 2022). "The Sexual Revolution Origins and Impact". study.com. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ "Playboy: American Magazine". Encyclopedia Britannica. August 25, 2022. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

...the so-called sexual revolution in the United States in the 1960s, marked by greatly more permissive attitudes toward sexual interest and activity than had been prevalent in earlier generations.

- ^ Levy, Daniel (January 19, 2018). "Behind the Protests Against the Vietnam War in 1968". Time. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Gaĭdar, E.T. (2007). Collapse of an Empire: Lessons for Modern Russia. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. pp. 190–205. ISBN 978-0-8157-3114-6.

- ^ Howell, Buddy Wayne (2006). The Rhetoric of Presidential Summit Diplomacy: Ronald Reagan and the U.S.-Soviet Summits, 1985–1988. Texas A&M University. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-549-41658-6.

- ^ Kissinger, Henry (2011). Diplomacy. Simon & Schuster. pp. 781–784. ISBN 978-1-4391-2631-8. Retrieved October 25, 2015. Mann, James (2009). The Rebellion of Ronald Reagan: A History of the End of the Cold War. Penguin. p. 432. ISBN 978-1-4406-8639-9.

- ^ Hayes, 2009

- ^ Walsh, Kenneth T. (December 9, 2008). "The 'War on Terror' Is Critical to President George W. Bush's Legacy". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved March 6, 2013. Atkins, Stephen E. (2011). The 9/11 Encyclopedia: Second Edition. ABC-CLIO. p. 872. ISBN 978-1-59884-921-9. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ Wong, Edward (February 15, 2008). "Overview: The Iraq War". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2013. Johnson, James Turner (2005). The War to Oust Saddam Hussein: Just War and the New Face of Conflict. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-7425-4956-2. Retrieved October 25, 2015. Durando, Jessica; Green, Shannon Rae (December 21, 2011). "Timeline: Key moments in the Iraq War". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 4, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ^ Hilsenrath, Jon; Ng, Serena; Paletta, Damian (September 18, 2008). "Worst Crisis Since '30s, With No End Yet in Sight". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 1042-9840. OCLC 781541372. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2023.

- ^ "Barack Obama: Face Of New Multiracial Movement?". NPR. November 12, 2008.

- ^ Washington, Jesse; Rugaber, Chris (July 10, 2011). "African-American Economic Gains Reversed By Great Recession". Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013.

- ^ Hamid, Shadi (2022-01-08). "The Forever Culture War". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2023-10-01.