User:DanaBell/sandbox

Impiety is a perceived lack of proper respect for something considered sacred.[1] Impiety is often closely associated with sacrilege, though it is not necessarily a physical action. Impiety cannot be associated with a cult, as it implies a larger belief system was disrespected. One of the Pagan objections to Christianity was that, unlike other mystery religions, early Christians refused to cast a pinch of incense before the images of the gods, an impious act in their eyes. Impiety in ancient civilizations was a civic concern, rather than religious. It was believed that impious actions such as disrespect towards sacred objects or priests could bring down the wrath of the gods. Impiety was often used to prosecute atheists.

Ancient Greece[edit]

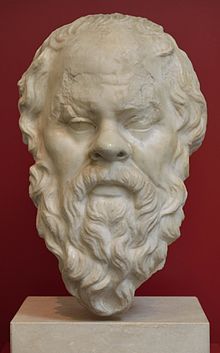

The issue of impiety in antiquity is very controversial because of the anecdotal nature of extant sources. A number of Athenian men, including Alcibiades, were sentenced to death for impiety in 415 BCE, most of whom fled Athens before execution[2]. Andocides was later charged in 400 or 399 BCE in reference to these events). Most famously, the philosopher Socrates was executed for impiety in 399 BCE. Socrates did make a vain attempt to contest the charge against him. The philosopher argued that he should be freed because he was being educated in piety from Euthyphro, an Athenian nobleman present during the court proceedings.[3] His strategy did not work and Socrates was forced to drink poisonous hemlock. An Athenian philosopher Anaxagoras taught that the sun and the stars were fiery stones whose heat we did not feel because of their distance, and was allegedly accused of impiety in Athens. Diagoras of Melos was reportedly accused of atheism and had to flee Athens after being charged with impiety for revealing the content of the Eleusinian mysteries to the uninitiated. Philosophers Aristotle and Theophrastus might have been accused of impiety and of disavowing the Greek Pantheon of Gods and he failed to utter a word in his defense at his Athenian trial, but due to his popularity he was easily acquitted.[4] Demetrius of Phalerum was accused of impiety, along with Theodorus of Cyrene. Stilpo the Greek philosopher was sentenced to exile for his supposed impiety, he claimed that Athena was not a God, because she came from the head of Zeus.[4]

Ancient Rome[edit]

In ancient Rome, Impiety was not a criminal matter. The Romans believed if someone willingly committed an act of impiety, the god themselves would extract vengeance upon the impious. So in most cases the Roman authorities took no action to punish impiety.[5] If Roman officers committed impieties during their service, the Roman authorities might come to the conclusion that the act of impiety was detrimental to the pax deorum, the mutually beneficial balance and peace with the gods. If the Roman senate found one of their officers guilty of an impiety, the senate would consult a priestly college and then conduct rites to remedy the impiety and protect the roman community from divine wrath.[5] Roman officer Pleminius was accused of Impiety in 205 B.C., when he allowed the Temple of Persephone in Epizephyrian Locri, South Italy, to be plundered during the Punic war against the Phoenicians.[5] The Roman officer's "soldiers raped, plundered and humiliated the city's inhabitants, and Pleminius and others looted the temples, including the treasury of the temple of Persephone."[5] As a consequence for his impiety, Pleminius was removed from office. In 173 B.C. Roman censor Qunitus Fulvius Flaccus was accused of impiety for appropriating Marble tiles from the temple of Hera Lacinia, near the Roman colony Crotóne.[5] The Roman senate immediately order the tiles to be returned and Flaccus died of an illness soon afterwords,

Thomas Harriot[edit]

British Astronomer and Mathematician Thomas Harriot (1560-1621) was claimed to have contracted skin cancer on his face from his supposed impieties. Harriot made many astronomical discoveries that angered many religious leaders. Harriot was considered to be an atheist for his views about science and he was accused of denying the Old Testament and the Resurrection of Jesus Christ by several clergymen.[6] Christopher Marlowe and Sir Walter Ralegh were also accused of impiety around the same time. All three men were have said to have died from divine retribution on account of their impieties.

19th Century Italy[edit]

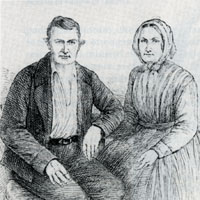

After a minor riot broke out in the Italian province of Tuscany in 1848, the Grand Duchy, Leopold II, suspended civil rights and outlawed Protestantism. Reading the bible in the vernacular became punishable by law. Among the people persecuted were the Madiai, a couple from Florence named Francesco and Rosa Madiai. To make a living the couple rented their lodging to travelers. Eventually they converted from Catholic to Protestant and in August 1851, their house was entered by Italian authorities who searched for copies of the bible. On 4 June 1852, after nine months of imprisonment the Madiais were brought to the Italian Royal Court for Impiety.[7] Although the prosecution found no evidence of direct political involvement, the Francesco and Rosa were found guilty and sentenced to 56 and 45 months respectively. After protests from notable figures like Prince Albert of England, the Madiais were released on 15 March 1853.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/impiety.

- Filonik, Jakub (2013). "Athenian impiety trials: a rester.com/dictionary/impietyappraisal". Dike. 16: 11–96. doi:10.13130/1128-8221/4290. ISSN 1128-8221.

- Edwards, G. F. 2016. How to Escape Indictment for Impiety: Teaching as Punishment in the Euthyphro. Journal of the History of Philosophy 54 (1): 1-19.

- O'Sullivan,L.-L. "Athenian Impiety Trials in the Late Fourth Century B. C." The Classical Quarterly 47, no. 1 (1997): 136-52. http://www.jstor.org/stable/639604.

- Wells, Jack. 2010. "Impiety in the Middle Republic: The Roman Response to Temple Plundering in Southern Italy." Classical Journal 105, no. 3: 229-243. Art Full Text (H.W. Wilson), EBSCOhost (accessed November 5, 2016).

- Jacquot, Jean. "Thomas Harriot's Reputation for Impiety." Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 9, no. 2 (1952): 164-87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3087213.

- Lohrli, Anne. 1989. "The Madiai: A Forgotten Chapter of Church History." Victorian Studies. 33, no. 1: 29.

- ^ "Merriam-Webster.com".

- ^ ""Athenian impiety trials"". Dike. 16.

- ^ "How to Escape Indictment for Impiety: Teaching as Punishment in the Euthyphro". Journal of the History of Philosophy. 54.

- ^ a b O'Sullivan, L-L. (1997). ""Athenian Impiety Trials in the Late Fourth Century B. C."". The Classical Quarterly. 47 (1): 136–52.

- ^ a b c d e Wells,, Jack (2010). ""Impiety in the Middle Republic: The Roman Response to Temple Plundering in Southern Italy."". Classical Journal. 105 (no. 3): 229–243.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ ""Thomas Harriot's Reputation for Impiety."". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 9.

- ^ Lohrli, Anne. ""The Madiai: A Forgotten Chapter of Church History"". Victorian Studies. 33.