User:Chunshengyan/Peptide vaccine

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

Peptide-based synthetic vaccines, also called epitope vaccines, are subunit vaccines made from peptides. The peptides mimic the epitopes of the antigen that triggers direct or potent immune responses. [1] Peptide vaccines can not only induce protection against infectious pathogens and non-infectious diseases but also be utilized as therapeutic cancer vaccines, where peptides from tumor-associated antigens are used to induce an effective anti-tumor T-cell response. [2]

History of Vaccine Evolution[3][edit]

The traditional vaccines are the whole live or fixed pathogens. The second generation of vaccines is mainly the protein purified from the pathogen. The third generation of vaccines is the DNA or plasmid that can express the proteins of the pathogen. Peptide vaccines are the latest step in the evolution of vaccines.

Advantages and Disadvantages [4][edit]

Compared with the traditional vaccines such as the whole fixed pathogens or protein molecules, the peptide vaccines have several advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages[edit]

- The vaccines are fully synthesized by chemical synthesis and can be treated as chemical entity.

- With more advanced solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) using automation and microwave techniques, the production of peptides becomes more efficient.

- The vaccines do not have any biological contamination since they are chemically synthesized.

- The vaccines are water-soluble and can be kept stable under simple conditions.

- The peptides can be specially designed for specificity. A single peptide vaccine can be designed to have multiple epitopes to generate immune responses for several diseases.

- The vaccines only contain a short peptide chain, so they are less like to lead to allergic or auto-immune responses.

Disadvantages[edit]

- Poor immunogenicity.

- Unstable in cells.

- Lack of native conformation.

- Only effective for a limited population.

Epitope Design[edit]

The whole peptide vaccine is to mimic the epitope of an antigen, so epitope design is the most important stage of vaccine development and requires an accurate understanding of the amino acid sequence of the immunogenic protein interested. The designed epitope is expected to generate strong and long-period immuno-response against the pathogen. The followings are the points to consider when designing the epitope:

- The non-dominant epitope could generate a stronger immune response than the dominant epitope. Ex. The antibodies from people infected by hookworm can recognize the dominant epitope of the antigen called Necator americanus APR-1 protein, but the antibodies can't induce protection against hookworm. However, other non-dominant epitopes on APR-1 protein show the ability to induce the production of neutralizing antibodies against hookworm. Therefore, the non-dominant epitopes are the better candidate for peptide vaccines against hookworm infection. [5]

- Take hypersensitivity into consideration. Ex. Some IgE-inducing epitopes cause hypersensitivity reactions after vaccination in humans due to the overlap with IgG epitopes in the Na-ASP-2 protein which is an antigen from hookworm. [6]

- Some short peptide epitopes need elongating to maintain the native conformation. The elongated sequences can include proper secondary structure. Also, some short peptides can be stabled or cyclized together to maintain the proper conformation. Ex. B-cell epitopes could only have 5 amino acids. To induce an immune response, a sequence from yeast GCN4 protein is used to improve the conformation of the peptide vaccines by forming alpha-helix. [7]

- Use adjuvants associated with the epitope to induce the immune response. [8]

Applications[edit]

Peptide vaccines for cancer[edit]

- Gp100 peptide vaccine is studied to treat melanoma. To generate a greater in vitro CTL response, the peptide, gp100:209-217(210M), is modified and binds to HLA-A2*0201. After vaccination, more circulating T cells can recognize and kill melanoma cancer cells in vitro. [10]

- Rindopepimut is the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-derived peptide vaccine to treat glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). The 14-mer peptide is coupled with keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH), which can reduce the risk of cancer. [11]

- E75, GP2, and AE37 are three different HER2/neu-derived single-peptide vaccines to treat breast cancer. HER2/neu usually has low expression in healthy tissues. E75 consisting of 9 amino acids is the immunodominant epitope of the HER2 protein. GP2 consisting of 9 amino acids is the subdominant epitope. Both E75 and GP2 stimulate the CD8+ lymphocytes but GP2 has a lower affinity than E75. AE37 stimulates CD4+ lymphocytes.[12]

Peptide vaccines for other common diseases[edit]

- EpiVacCorona, a peptide-based vaccine against COVID-19.

- IC41 is a peptide vaccine candidate against the Hepatitis C virus. It consists of five synthetic peptides along with the synthetic adjuvant called poly-l-arginine. [13]

- Multimeric-001 is the most efficient peptide vaccine candidate against influenza. It contains B- and T-cell epitopes from Hemagglutinin. Matrix I and nucleoprotein are combined into a single recombinantly-expressed polypeptide. [14] [15]

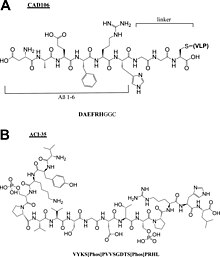

- Alzheimer peptide vaccines: CAD106[16], UB311[17], Lu, AF20513[18], ABvac40[19], ACI-35[20], AADvac-1[21].

References[edit]

- ^ Skwarczynski, Mariusz; Toth, Istvan (2016). "Peptide-based synthetic vaccines". Chemical Science. 7 (2): 842–854. doi:10.1039/C5SC03892H. ISSN 2041-6520. PMC 5529997. PMID 28791117.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Melief, Cornelis J.M.; van der Burg, Sjoerd H. (2008-05-01). "Immunotherapy of established (pre)malignant disease by synthetic long peptide vaccines". Nature Reviews Cancer. 8 (5): 351–360. doi:10.1038/nrc2373. ISSN 1474-1768.

- ^ Schneble, Erika; Clifton, G. Travis; Hale, Diane F.; Peoples, George E. (2016), Thomas, Sunil (ed.), "Peptide-Based Cancer Vaccine Strategies and Clinical Results", Vaccine Design: Methods and Protocols: Volume 1: Vaccines for Human Diseases, Methods in Molecular Biology, New York, NY: Springer, pp. 797–817, doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-3387-7_46, ISBN 978-1-4939-3387-7, retrieved 2021-11-16

- ^ Skwarczynski, Mariusz; Toth, Istvan (2016). "Peptide-based synthetic vaccines". Chemical Science. 7 (2): 842–854. doi:10.1039/C5SC03892H. ISSN 2041-6520. PMC 5529997. PMID 28791117.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Pearson, Mark S.; Pickering, Darren A.; Tribolet, Leon; Cooper, Leanne; Mulvenna, Jason; Oliveira, Luciana M.; Bethony, Jeffrey M.; Hotez, Peter J.; Loukas, Alex (2010-05-15). "Neutralizing Antibodies to the Hookworm Hemoglobinase Na ‐APR‐1: Implications for a Multivalent Vaccine against Hookworm Infection and Schistosomiasis". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 201 (10): 1561–1569. doi:10.1086/651953. ISSN 0022-1899.

{{cite journal}}: no-break space character in|first2=at position 7 (help); no-break space character in|first6=at position 8 (help); no-break space character in|first7=at position 8 (help); no-break space character in|first8=at position 6 (help); no-break space character in|first=at position 5 (help) - ^ Diemert, David J.; Pinto, Antonio G.; Freire, Janaina; Jariwala, Amar; Santiago, Helton; Hamilton, Robert G.; Periago, Maria Victoria; Loukas, Alex; Tribolet, Leon; Mulvenna, Jason; Correa-Oliveira, Rodrigo (2012-07). "Generalized urticaria induced by the Na-ASP-2 hookworm vaccine: Implications for the development of vaccines against helminths". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 130 (1): 169–176.e6. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.04.027.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Cooper, Juan A.; Hayman, Wendy; Reed, Carol; Kagawa, Hiroaki; Good, Michael F.; Saul, Allan (1997-04). "Mapping of conformational B cell epitopes within alpha-helical coiled coil proteins". Molecular Immunology. 34 (6): 433–440. doi:10.1016/S0161-5890(97)00056-4.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Azmi, Fazren; Ahmad Fuaad, Abdullah Al Hadi; Skwarczynski, Mariusz; Toth, Istvan (2014-03). "Recent progress in adjuvant discovery for peptide-based subunit vaccines". Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 10 (3): 778–796. doi:10.4161/hv.27332. ISSN 2164-5515. PMC 4130256. PMID 24300669.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Malonis, Ryan J.; Lai, Jonathan R.; Vergnolle, Olivia (2020-03-25). "Peptide-Based Vaccines: Current Progress and Future Challenges". Chemical Reviews. 120 (6): 3210–3229. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00472. ISSN 0009-2665. PMC 7094793. PMID 31804810.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Marincola, Francesco M.; Rivoltini, Licia; Salgaller, Michael L.; Player, Maryanne; Rosenberg, Steven A. (1996-07). "Differential Anti-MART-1/MelanA CTL Activity in Peripheral Blood of HLA-A2 Melanoma Patients in Comparison to Healthy Donors". Journal of Immunotherapy. 19 (4): 266–277. doi:10.1097/00002371-199607000-00003. ISSN 1524-9557.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Neal, David E.; Sharples, Linda; Smith, Kenneth; Fennelly, Janet; Hall, Reg R.; Harris, Adrian L. (1990-04-01). <1619::aid-cncr2820650728>3.0.co;2-q "The epidermal growth factor receptor and the prognosis of bladder cancer". Cancer. 65 (7): 1619–1625. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19900401)65:7<1619::aid-cncr2820650728>3.0.co;2-q. ISSN 0008-543X.

- ^ Palatnik-de-Sousa, Clarisa Beatriz; Soares, Irene da Silva; Rosa, Daniela Santoro (2018-04-18). "Editorial: Epitope Discovery and Synthetic Vaccine Design". Frontiers in Immunology. 9: 826. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00826. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 5915546. PMID 29720983.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Firbas, Christa; Jilma, Bernd; Tauber, Erich; Buerger, Vera; Jelovcan, Sandra; Lingnau, Karen; Buschle, Michael; Frisch, Jürgen; Klade, Christoph S. (2006-05). "Immunogenicity and safety of a novel therapeutic hepatitis C virus (HCV) peptide vaccine: A randomized, placebo controlled trial for dose optimization in 128 healthy subjects". Vaccine. 24 (20): 4343–4353. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.009. ISSN 0264-410X.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Atsmon, Jacob; Caraco, Yoseph; Ziv-Sefer, Sagit; Shaikevich, Dimitry; Abramov, Ester; Volokhov, Inna; Bruzil, Svetlana; Haima, Kirsten Y.; Gottlieb, Tanya; Ben-Yedidia, Tamar (2014-10). "Priming by a novel universal influenza vaccine (Multimeric-001)—A gateway for improving immune response in the elderly population". Vaccine. 32 (44): 5816–5823. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.08.031. ISSN 0264-410X.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ van Doorn, Eva; Liu, Heng; Ben-Yedidia, Tamar; Hassin, Shimon; Visontai, Ildiko; Norley, Stephen; Frijlink, Henderik W.; Hak, Eelko (2017-03). "Evaluating the immunogenicity and safety of a BiondVax-developed universal influenza vaccine (Multimeric-001) either as a standalone vaccine or as a primer to H5N1 influenza vaccine". Medicine. 96 (11): e6339. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000006339. ISSN 0025-7974.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Wiessner, C.; Wiederhold, K.-H.; Tissot, A. C.; Frey, P.; Danner, S.; Jacobson, L. H.; Jennings, G. T.; Luond, R.; Ortmann, R.; Reichwald, J.; Zurini, M. (2011-06-22). "The Second-Generation Active A Immunotherapy CAD106 Reduces Amyloid Accumulation in APP Transgenic Mice While Minimizing Potential Side Effects". Journal of Neuroscience. 31 (25): 9323–9331. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0293-11.2011. ISSN 0270-6474.

{{cite journal}}: no-break space character in|title=at position 31 (help) - ^ Wang, Chang Yi; Finstad, Connie L.; Walfield, Alan M.; Sia, Charles; Sokoll, Kenneth K.; Chang, Tseng-Yuan; Fang, Xin De; Hung, Chung Ho; Hutter-Paier, Birgit; Windisch, Manfred (2007-04). "Site-specific UBITh® amyloid-β vaccine for immunotherapy of Alzheimer's disease". Vaccine. 25 (16): 3041–3052. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.031. ISSN 0264-410X.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Davtyan, H.; Ghochikyan, A.; Petrushina, I.; Hovakimyan, A.; Davtyan, A.; Poghosyan, A.; Marleau, A. M.; Movsesyan, N.; Kiyatkin, A.; Rasool, S.; Larsen, A. K. (2013-03-13). "Immunogenicity, Efficacy, Safety, and Mechanism of Action of Epitope Vaccine (Lu AF20513) for Alzheimer's Disease: Prelude to a Clinical Trial". Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (11): 4923–4934. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.4672-12.2013. ISSN 0270-6474.

- ^ Molina, Elisabet P.; Pesini, Pedro; Sarasa‐SanJose, Manuel; Marcos, Ivan; Lacosta, Ana M.; Allué, Jose A.; Fandos, Noelia; Sarasa, Manuel; Boada, Mercè (2020-12). "Safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of an active anti‐Aβ40 vaccine (ABvac40) in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (A‐MCI) or very mild alzheimer's disease (VM‐AD): A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase II trial". Alzheimer's & Dementia. 16 (S9). doi:10.1002/alz.045720. ISSN 1552-5260.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hickman, David T.; López-Deber, María Pilar; Ndao, Dorin Mlaki; Silva, Alberto B.; Nand, Deepak; Pihlgren, Maria; Giriens, Valérie; Madani, Rime; St-Pierre, Annie; Karastaneva, Hristina; Nagel-Steger, Luitgard (2011-04). "Sequence-independent Control of Peptide Conformation in Liposomal Vaccines for Targeting Protein Misfolding Diseases". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (16): 13966–13976. doi:10.1074/jbc.m110.186338. ISSN 0021-9258.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kontsekova, Eva; Zilka, Norbert; Kovacech, Branislav; Novak, Petr; Novak, Michal (2014). "First-in-man tau vaccine targeting structural determinants essential for pathological tau–tau interaction reduces tau oligomerisation and neurofibrillary degeneration in an Alzheimer's disease model". Alzheimer's Research & Therapy. 6 (4): 44. doi:10.1186/alzrt278. ISSN 1758-9193.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)