User:Borzism/sandbox

Cultural diplomacy a type of public diplomacy and soft power that includes "exchange of ideas, information, art and other aspects of culture among nations and their peoples in order to foster mutual understanding."[1] The purpose of cultural diplomacy is for the people of a foreign nation to develop an understanding of the nation's ideals and institutions in an effort to build broad support for economic and political goals.[2] In essence "cultural diplomacy reveals the soul of a nation," which in turn creates influence.[3] Though often overlooked, cultural diplomacy can and does play an important role in achieving national security aims.

Definition[edit]

Culture is a set of values and practices that create meaning for society. This includes both high culture (literature, art, and education, which appeals to elites) and popular culture (appeals to the masses).[4] This is what governments seek to show foreign audiences when engaging in cultural diplomacy. It is a type of soft power, which is the "ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion or payments. It arises from a country's culture, political ideals and policies."[5] This indicates that the value of culture is its ability to attract foreigners to a nation. Cultural diplomacy is also a component of public diplomacy. Public diplomacy is enhanced by a larger society and culture, but simultaneously public diplomacy helps to "amplify and advertise that society and culture to the world at large.”[6] It could be argued that the information component of public diplomacy can only be fully effective where there is already a relationship that gives credibility to the information being relayed. This comes from knowledge of the other’s culture.”[7] Cultural diplomacy has been called the “linchpin of public diplomacy” because cultural activities have the possibility to demonstrate the best of a nation. [8] In this way, cultural diplomacy and public diplomacy are intimately linked.

Richard T. Arndt, a former State Department cultural diplomacy practitioner, said "Cultural relations grow naturally and organically, without government intervention – the transactions of trade and tourism, student flows, communications, book circulation, migration, media access, inter-marriage – millions of daily cross-cultural encounters. If that is correct, cultural diplomacy can only be said to take place when formal diplomats, serving national governments, try to shape and channel this natural flow to advance national interests.”[9] It is important to note that, while cultural diplomacy is, as indicated above, a government activity, the private sector has a very real role to play because the government does not create culture, therefore, it can only attempt to make a culture known and define the impact this organic growth will have on national policies. Cultural diplomacy attempts to manage the international environment by utilizing these sources and achievements and making them known abroad. [10] An important aspect of this is listening- cultural diplomacy is meant to be a two-way exchange.[11] This exchange is then intended to foster a mutual understanding and thereby win influence within the target nation. Cultural diplomacy derives its credibility not from being close to government institutions, but from its proximity to cultural authorities.[12]

Purpose[edit]

Ultimately, the goal of cultural diplomacy is to influence a foreign audience and use that influence, which is built up over the long term, as a sort of good will reserve to win support for policies. It seeks to harness the elements of culture to induce foreigners to:[13]

- have a positive view of the country's people, culture and policies,

- induce greater cooperation between the two nations,

- aid in changing the policies or political environment of the target nation,

- prevent, manage and mitigate conflict with the target nation .

In turn, cultural diplomacy can help a nation better understand the foreign nation it is engaged with and foster mutual understanding. Cultural diplomacy is a way of conducting international relations without expecting anything in return in the way that traditional diplomacy typically expects.[14]

Generally, cultural diplomacy is more focused on the longer term and less on specific policy matters.[15] The intent is to build up influence over the long term for when it is needed by engaging people directly. This influence has implications ranging from national security to increasing tourism and commercial opportunities.[16] It allows the government to create a "foundation of trust" and a mutual understanding that is neutral and built on people-to-people contact. Another unique and important element of cultural diplomacy is its ability to reach youth, non-elites and other audiences outside of the traditional embassy circuit. In short, cultural diplomacy plants the seeds of ideals, ideas, political arguments, spiritual perceptions and a general view point of the world that may or may not flourish in a foreign nation.[17]

Link to National Security[edit]

First and foremost, cultural diplomacy is a demonstration of national power because it demonstrates to foreign audiences every aspect of culture, including wealth, scientific and technological advances, competiveness in everything from sports and industry to military power, and a nation's overall confidence.[18] The perception of power obviously has important implications for a nation's ability to ensure its security. Furthermore because cultural diplomacy includes political and ideological arguments, and uses the language of persuasion and advocacy, it can be used as an instrument of political warfare and be useful in achieving traditional goals of war.[19] A Chinese activist was quoted as saying "We’ve seen a lot of Hollywood movies- they feature weddings, funerals and going to court. So now we think it’s only natural to go to court a few times in your life.”[20] This is an example of a cultural export- Hollywood movies, possibly having a subtle effect on the legal system in China, which could ultimately benefit the United States or any other nation which wishes to see a more democratic China. This is the way in which ideas and perceptions can ultimately affect the ability of a nation to achieve its national security goals.

In terms of policy that supports national security goals, the information revolution has created an increasingly connected world in which public perceptions of values and motivations can create an enabling or disabling environment in the quest for international support of policies.[21] The struggle to affect important international developments is increasingly about winning the information struggle to define the interpretation of states' actions. If an action is not interpreted abroad as the nation meant to it be, then the action itself can become meaningless.[22] Cultural diplomacy can create an environment in which a nation is received as basically good, which in turn can help frame its actions in a positive light.

Participants in cultural diplomacy often have insights into foreign attitudes that official embassy employees do not. This can be used to better understand a foreign nation’s intentions and capabilities. It can also be used to counter hostile propaganda and the collection of open source intelligence.[23]

Overall, cultural diplomacy has the potential to demonstrate national power, create an environment conducive to support, and assist in the collection and interpretation of information. This, in turn, aids in the interpretation of intelligence, enhances a nation's prestige and aids in garnering support for policies abroad. All of these factors affect a nation's security, thus, cultural diplomacy has an effect on, and a role to play, in regards to national security.

Tools and Examples[edit]

Cultural diplomacy can and does utilize every aspect of a nation’s culture. This includes:[24]

- The arts including films, dance, music, painting, sculpture, etc.

- Exhibitions which offer the potential to showcase numerous objects of culture

- Educational programs such as universities and language programs abroad

- Exchanges- scientific, artistic, educational etc.

- Literature- the establishment of libraries abroad and translation of popular and national works

- Broadcasting of news and cultural programs

- Gifts to a nation, which demonstrates thoughtfulness and respect

- Religious diplomacy, including inter-religious dialogue

- Promotion and explanation of ideas and social policies

All of these tools seek to bring understanding of a nation's culture to foreign audiences. They work best when they are proven to be relevant to the target audience, which requires an understanding of the audience. The tools can be utilized by working through NGOs, diasporas and political parties abroad, which may help with the challenge of relevance and understanding.[25] These tools are generally not created by a government, but produced by the culture and then the government facilitates their expression abroad to a foreign audience, with the purpose of gaining influence.

The Arts[edit]

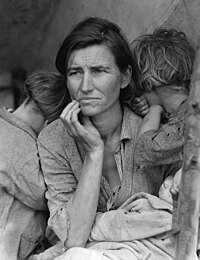

In the 1950's the Soviet Union had a reputation that was associated with peace, international class solidarity and progress due to its sponsorship of local revolutionary movements for liberation. The United States was known for its involvement in the Korean War and for preserving the status quo. In an effort to change this perception, the United States Information Agency (USIA) sponsored a photographic exhibition titled The Family of Man. The display originally showed in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, but then USIA helped the display to be seen in 91 locations in 39 countries. The 503 photographs by 237 professional and amateur photographers were curated and put together by Edward Steichen. The images showed glimpses of everyday human life in its various stages; courtship, birth, parenting, work, self-expression, etc., including images from the Great Depression. The images were multi-cultured and only a few were overtly political serving to show the eclecticism and diversity of American culture, which is America's soft power foundation. The display was extremely popular and attracted large numbers of crowds, in short America "showed the world, the wold and got credit for it."[26]

A similar effort was carried out by the United States Department of State in February 2002 entitled Images from Ground Zero. The display included 27 images, detailing the September 11 attacks by Joel Meyerowitz that circulated, with the backing of embassies and consulates, to 60 nations. The display was intended to shape and maintain the public memory of the attack and its aftermath. The display sought to show the human side of the tragedy, and not just the destruction of buildings. The display was also intended to show a story of recovery and resolution through documenting not only the grief and pain, but also the recovery efforts. In many countries where the display was ran, it was personalized for the population. For example, relatives of those who died in the Towers were often invited to the event openings.[27] In this way, the US was able to put their own spin on the tragedy and keep the world from forgetting.

Exhibitions[edit]

Exhibitions were often used during the Cold War to demonstrate culture and progress by both the United States and the Soviet Union. In 1959, the American National Exhibition was held on Sokolniki Park, which was only 15 minutes from the Red Square by Subway. The exhibition was opened by Vice President Richard Nixon and attended by Walt Disney, Buckminster Fuller, William Randolph Hearst, and senior executives from Pepsi, Kodak and Macy's. It featured American consumer goods, cars, boats, RCA color TVs, food, clothing, etc, and samples of American products such as Pepsi. There was a typical American kitchen set up inside in which spectators could watch a Bird's Eye frozen meal be prepared. An IBM RAMAC computer was programmed to answer 3,500 questions about America in Russian. The most popular question was "what is the meaning of the American Dream?" The Soviets tried to limit the audience by only giving tickets to party members and setting up their own rival exhibition. But ultimately people came, and the souvenir pins that were given out turned up in every corner of the country. The Soviets banned printed material, but the Americans gave it out anyway. The most popular items were the Bible and a Sears catalogue. The guides for the exhibition were American graduate students, including African Americans and women, who spoke Russian. This gave Russians the ability to speak to real Americans and ask difficult questions. The ambassador to Moscow, Llewellyn Thompson, commented that "the exhibition would be ‘worth more to us than five new battleships."[28] Exhibitions like this were used to display the best a culture had to offer and basically show off in a way that appeared non threatening and even friendly.

Exchanges[edit]

The usefulness of exchanges is based on two assumptions- some form of political intent lies behind the exchange and the result will have some sort of political effect. The idea is that exchanges will create a network of influential people abroad that will tie them to their host country and will appreciate their host country more due to their time spent there.[29] Exchanges generally take place at a young age, giving the host country the opportunity to create an attachment and gain influence at a young impressionable age.[30]

An example of the possible usefulness of exchanges is provided by the United States Fulbright Program. Some statistics include:[31]

- 44 alumni from 12 countries have been awarded the Nobel Prize

- 81 alumni have received Pulitzer Prizes

- 29 Fulbright alumni have served as heads of state or government

Some Prominent Fulbright alumni include:

- Garry Conille, Former Prime Minister of Haiti

- Muhammad Yunus, Founder of Grameen Bank and 2006 Nobel Peace Prize recipient

- John Atta Mills, President of Ghana

- Lee Evans, Olympic Gold Medalist

- Riccardo Giacconi, physicist and 2002 Nobel Laureate

- Renée Fleming, soprano

- Jonathan Franzen, writer

This is not to say that exchanges guarantee that participants will look favorably upon their host nation, but the hope is that they will.

TV, music, film[edit]

Popular entertainment is a statement about the society which it is portraying. These cultural displays can carry important subliminal messages regarding individualism, consumer choices and other values. For example, Soviet audiences watching American films learned that Americans owned their own cars, did not have to stand in long lines to purchase food, and did not live in communal apartments.[32] These observations were not intended to be political messages when Hollywood created the films, but they none-the-less carried a message.

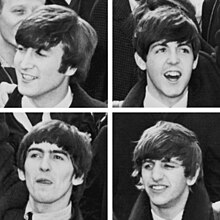

The effect The Beatles had in Russia during the Cold War is an example of how music artists and their songs can become political. Kolya Vasin, the founder of The Beatles museum and the Temple of Love, Peace and Music in St. Petersburg,[33] commented that The Beatles "were like an integrity test. When anyone said anything against them, we knew just what that person was worth. The authorities, our teachers, even our parents, became idiots to us."[34] Leslie Woodland, a documentary film maker, commented regarding what the Russian people were told about the West - “Once people heard the Beatles' wonderful music, it just didn't fit. The authorities' prognosis didn't correspond to what they were listening to. The system was built on fear and lies, and in this way, the Beatles put an end to the fear, and exposed the lies."[35] In this way the music of The Beatles struck a political cord in the Soviet Union, even when the songs were not meant to be political. This contact went both ways. In 1988, when the song “Back in the USSR” was released, the album included a quote on the cover from Paul McCartney that read “In releasing this record, made especially and exclusively for the USSR, I am extending a hand of peace and friendship to the Soviet people.”[36] This is an example of how products of culture can have an influence on the people they reach outside of their own country. It also shows how a private citizen can unintentionally become a cultural ambassador of sorts.

Place Branding[edit]

Image and reputation has become an essential part of a “state’s strategic equity.” Place branding is "the totality of the thoughts, feelings, associations and expectations that come to mind when a prospect or consumer is exposed to an entity's name, logo, products, services, events, or any design or symbol representing them." Place branding is required to make a country’s image acceptable for investment, tourism, political power, etc. As Joseph Nye commented, “in an information age, it is often the side which has the better side of the story that wins,” this has resulted in a shift from old style diplomacy to encompass brand building and reputation management. In short, a country can use its culture to create a brand for itself which represents positive values and image.[37]

Complications of Cultural Diplomacy[edit]

Cultural diplomacy presents a number of unique challenges to any government attempting to carry out cultural diplomacy programs. Most ideas that a foreign population observes are not in the government's control. The government does not, and should not, produce the books, music, films, TV programs, consumer products, etc. that reaches an audience. The most the government can do is try to work to create opening so the message can get through to mass audiences abroad.[38] To be cultural relevant in the age of globalization, a government must exercise control over the flows of information and communication technologies, including trade.[39] This is also difficult for governments that operate in a free market society where the government does not control the bulk of information flows. What the government can do is work to protect cultural exports where they flourish, by utilizing trade agreements or gaining access for foreign telecommunication networks.[40]

It is also possible that foreign government officials may oppose or resist certain cultural exports while the people cheer them on. This can make support for official policies difficult to obtain.[41] Cultural activities may be both a blessing and a curse to a nation. This may be the case if certain elements of a culture are offensive to the foreign audience. Certain cultural activities can also undermine national policy objectives. An example of this was the very public American dissent to the Iraq War while official government policy still supported it.[42] Simultaneously the prevalence of the protest may have attracted some foreigners to the openness of America.[43] The success of cultural diplomacy is also extremely difficult to measure.

Institutions Dedicated to Cultural Diplomacy[edit]

United States Information Agency, United States (1953-1999)

Goethe Institute (Germany)

Confucius Institute (People's Republic of China)

British Council (United Kingdom)

Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, United States

Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs, France

Australia International Cultural Council, Australia

Japan Foundation, Japan

Alliance française, France

See Also[edit]

United States Information Agency

Bureau of International Information Programs

Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs

References[edit]

- ^ "Cultural Diplomacy, Political Influence, and Integrated Strategy," in Strategic Influence: Public Diplomacy, Counterpropaganda, and Political Warfare, ed. Michael J. Waller (Washington, DC: Institute of World Politics Press, 2009), 74.

- ^ Mary N. Maack, "Books and Libraries as Instruments of Cultural Diplomacy in Francophone Africa during the Cold War," Libraries & Culture 36, no. 1 (Winter 2001): 59.

- ^ United States, Department of State, Advisory Committee on Cultural Diplomacy, Diplomacy Report of the Advisory Committee on Cultural Diplomacy, 3.

- ^ Joseph S. Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (Cambridge: Perseus Books, 2004), 22.

- ^ Joseph S. Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (Cambridge: Perseus Books, 2004), 18.

- ^ Carnes Lord, Losing Hearts and Minds?: Public Diplomacy and Strategic Influence in the Age of Terror (Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, 2006), 15.

- ^ Carnes Lord, Losing Hearts and Minds?: Public Diplomacy and Strategic Influence in the Age of Terror (Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, 2006), 30.

- ^ United States, Department of State, Advisory Committee on Cultural Diplomacy, Diplomacy Report of the Advisory Committee on Cultural Diplomacy, 3.

- ^ "Cultural Diplomacy, Political Influence, and Integrated Strategy," in Strategic Influence: Public Diplomacy, Counterpropaganda, and Political Warfare, ed. Michael J. Waller (Washington, DC: Institute of World Politics Press, 2009), 74-75.

- ^ Nicholas J. Cull, "Public Diplomacy: Taxonomies and Histories," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616 (March 2008): 33.

- ^ United States, Department of State, Advisory Committee on Cultural Diplomacy, Diplomacy Report of the Advisory Committee on Cultural Diplomacy, 7 .

- ^ Nicholas J. Cull, "Public Diplomacy: Taxonomies and Histories," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616 (March 2008): 36.

- ^ "Cultural Diplomacy, Political Influence, and Integrated Strategy," in Strategic Influence: Public Diplomacy, Counterpropaganda, and Political Warfare, ed. Michael J. Waller (Washington, DC: Institute of World Politics Press, 2009), 77.

- ^ "Cultural Diplomacy, Political Influence, and Integrated Strategy," in Strategic Influence: Public Diplomacy, Counterpropaganda, and Political Warfare, ed. Michael J. Waller (Washington, DC: Institute of World Politics Press, 2009), 89.

- ^ Carnes Lord, Losing Hearts and Minds?: Public Diplomacy and Strategic Influence in the Age of Terror (Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, 2006), 30.

- ^ Mark Leonard, "Diplomacy by Other Means," Foreign Policy 132 (September/October 2002): 51.

- ^ United States, Department of State, Advisory Committee on Cultural Diplomacy, Diplomacy Report of the Advisory Committee on Cultural Diplomacy, 3, 4, 9.

- ^ "Cultural Diplomacy, Political Influence, and Integrated Strategy," in Strategic Influence: Public Diplomacy, Counterpropaganda, and Political Warfare, ed. Michael J. Waller (Washington, DC: Institute of World Politics Press, 2009), 76.

- ^ "Cultural Diplomacy, Political Influence, and Integrated Strategy," in Strategic Influence: Public Diplomacy, Counterpropaganda, and Political Warfare, ed. Michael J. Waller (Washington, DC: Institute of World Politics Press, 2009), 93.

- ^ Joseph S. Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (Cambridge: Perseus Books, 2004), 23.

- ^ Mark Leonard, "Diplomacy by Other Means," Foreign Policy 132 (September/October 2002): 49.

- ^ Jamie Frederic Metzl, "Popular Diplomacy," Daedalus 128, no. 2 (Spring 1999): 178.

- ^ "Cultural Diplomacy, Political Influence, and Integrated Strategy," in Strategic Influence: Public Diplomacy, Counterpropaganda, and Political Warfare, ed. Michael J. Waller (Washington, DC: Institute of World Politics Press, 2009), 78-79.

- ^ "Cultural Diplomacy, Political Influence, and Integrated Strategy," in Strategic Influence: Public Diplomacy, Counterpropaganda, and Political Warfare, ed. Michael J. Waller (Washington, DC: Institute of World Politics Press, 2009), 82-87.

- ^ Mark Leonard, "Diplomacy by Other Means," Foreign Policy 132 (September/October 2002): 51, 52.

- ^ Nicholas J. Cull, "Public Diplomacy: Taxonomies and Histories," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616 (March 2008): 39-40.

- ^ Liam Kennedy, "Remembering September 11: Photography as Cultural Diplomacy," International Affairs 79, no. 2 (March 2003): 315-323.

- ^ Nicholas John. Cull, The Cold War and the United States Information Agency: American Propaganda and Public Diplomacy, 1945-1989 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 162-167.

- ^ Giles Scott-Smith, "Mapping the Undefinable: Some Thoughts on the Relevance of Exchange Programs within International Relations Theory," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 16 (March 2008): 174.

- ^ Carnes Lord, Losing Hearts and Minds?: Public Diplomacy and Strategic Influence in the Age of Terror (Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, 2006), 30.

- ^ http://eca.state.gov/fulbright/fulbright-alumni/notable-fulbrighters

- ^ Carnes Lord, Losing Hearts and Minds?: Public Diplomacy and Strategic Influence in the Age of Terror (Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, 2006), 52.

- ^ http://www.something-books.com/index.php/Kolya-Vasin/menu-id-136.html

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2013/apr/20/beatles-soviet-union-first-rip-iron-curtain

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2013/apr/20/beatles-soviet-union-first-rip-iron-curtain

- ^ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/sponsored/russianow/culture/9663838/beatles-ussr-soviet-russia.html

- ^ Peter Van Ham, "Place Branding: The State of the Art," The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616 (March 2008): 127-133, doi:10.1177/0002716207312274.

- ^ Mark Leonard, "Diplomacy by Other Means," Foreign Policy 132 (September/October 2002): 50.

- ^ Louis Belanger, "Redefining Cultural Diplomacy: Cultural Security and Foreign Policy in Canada," Political Psychology 20, no. 4 (December 1999): 677-8, doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00164.

- ^ Louis Belanger, "Redefining Cultural Diplomacy: Cultural Security and Foreign Policy in Canada," Political Psychology 20, no. 4 (December 1999): 678, doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00164.

- ^ Joseph S. Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (Cambridge: Perseus Books, 2004), 56.

- ^ "Cultural Diplomacy, Political Influence, and Integrated Strategy," in Strategic Influence: Public Diplomacy, Counterpropaganda, and Political Warfare, ed. Michael J. Waller (Washington, DC: Institute of World Politics Press, 2009), 93.

- ^ Joseph S. Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (Cambridge: Perseus Books, 2004), 56.