User:Amir Ghandi/Safavid pretenders

The Fall of Isfahan in 1722 marked the end of 220-years-old rule of the Safavid dynasty in Iran. However, the prestige of this dynasty did not fade away and the instability that its fall left behind produced for a thousand years a series of Safavid pretenders (Persian: مدعیان سلطنت صفوی) who appeared at different times and places from the beginning of the Hotak dynasty's rule in Isfahan through the reign of Nader Shah Afshar and into that of Karim Khan Zand. Of these pretenders, only two legitimately claimed descendant from the Safavid stock, Tahmasp II and Shah Ahmad Marashi, while others were spurious. A few of them successfully ascended the throne, although reigned only as figureheads whereas others only sparked short-lived rebellion.

The first pretenders emerged immediately after the Siege of Isfahan, with Tahmasp II, the third son of Soltan Hoseyn, having established himself in Qazvin, calling out for support, and many false pretenders raising arms against the Afghan regime in various regions of Iran. The future Nader Shah raised in power as Tahmasp II's advisor and later the regent for his son, Abbas III.

Background[edit]

For the last half century of its political existence, the Safavid realm was no longer a functioning state, but only a declining corpse, devoured by excesses of debauchery and cruelty of its eighth Shah, Suleiman I in contrast with the overabundance of piety and pacifism of his successor, Soltan Hoseyn.[1] It is, in fact, more surprising that the Safavid state could survive this long rather than its sudden inevitable demise.[2] In March 1722, Soltan Hoseyn confronted the Afghan warlord, Mahmud Hotak and his army of ten thousand in Golunabad (Now known as Jilanabad). The Battle ended with the humiliating defeat of Safavids.[3] After this victory, Mahmud Hotak besieged the capital Isfahan, which lasted from March to October.[4] In April, Soltan Hoseyn had his third son, Tahmasp, sneaked out of the city. Tahmasp thereupon fled to Qazvin and stayed there for the rest of the siege.[5]

Eventually, the city fell into the Afghan hands in 23 October as Soltan Hoseyn surrendered himself to Mahmud Hotak.[6] After his surrender, the former shah was locked up in the palace with most of his family.[7] In February 1725, the Afghan warlord ordered the mass murder of every Safavid prince, including Soltan Hoseyn's sons, uncles and brothers. However, he let two youngest sons of Soltan Hoseyn to live. It may be that over a hundred of the royal family died in the massacre.[8] Shortly after this incident, Mahmud himself died in April 1725 and was succeeded by his cousin, Ashraf.[9] Soltan Hoseyn was finally executed by Ashraf's orders in Autumn 1727, beheaded in the Hall of Mirrors of his palace, where he could see his face as he was being executed.[8] His abdication and death marked the end of effective Safavid rule, even though, formally speaking, the Safavids continued to govern until 1732.[3]

Spurious pretenders[edit]

Afghan period[edit]

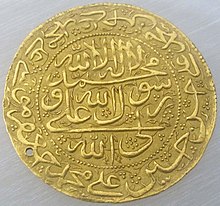

According to Hazin Lahiji, a poet contemporary of this era, eighteen pretenders rose from the time after the Siege of Isfahan and the 1726 massacre who claimed to be one of the princes who had escaped death. Many other names can be called from the various Afsharid chronicles like the Fawa'id al-Safawiyya by Abu'l-Hassan Qazvini that covers the whole period up to 1776.[10][a] Three of the first pretenders to appear after the Fall of Isfahan all claimed to be Safi Mirza, the second son of Soltan Hoseyn. One successfully drove out the Ottomans from Hamadan with the help of Lurs of Kermanshah; but five years later, the Lur chiefs turned against him and bribed a barber to assassinate him in his bath.[10] Another claimant, from the village of Korai, near Shushtar, acquired the support of Bakhtiari tribes. At first, he recognised Tahmasp II as the legitimate shah and had coins struck in his name.[11] However, In late 1724, he assumed the royal title 'Safi Shah' and with an army of 20,000 secured much of Kohgiluyeh county, between Shushtar and Khuramabad. As a result, Tahmasp II sent a letter to Bakhtiari chiefs and denounced him as an imposer and ordered his death, which they perpetrated in Autumn 1727.[10]

A third Safi Mirza, whose real name was Mohammad Ali Rafsanjani, likewise manifested in Shushtar in August 1729, wearing Dervish clothing. He was soon forced to leave the city by the governor and fled towards the western frontier, where the Ottoman authorities sent him to Istanbul in 1730 to keep him as a puppet leader to replace the Afghans.[10] None of these claimants are regarded as genuine by the historians. The real Safi Mirza, then aged 23, was appointed co-monarch by his father at the peak of the siege of Isfahan, but when he spoke harshly of maladministration of his father's administers and chastened the failed commanders of the Battle of Gulnabad, the courtiers took offence and forced the shah to banish the prince into the depths of the harem.[4] He was presumably amongst the other Safavid princes in the palace when his father surrendered the city to Mahmud Hotak, and most likely died in the 1726 massacre with all his kinsmen.[10] Ironically, it was the emergence of the first false Safi that prompted Mahmud Hotak to massacre the royal family.[8]

Some of the pretenders claimed to be the surviving brothers of Soltan Hoseyn. A certain Sayyid Hossein of Farah, who had accompanied the Afghan army as a wandering dervish, set up in Shahr-e Kord and claimed to be the brother of Soltan Hoseyn in 1724, after the news of the second Safi Mirza reached there.[12] The people of Shahr-e Kord had a reputation for addiction to tobacco, and a considerable amount of them pledged themselves to Sayyid Hossein. However, an Afghan force from Isfahan scattered them and killed Sayyid Hossein.[12]

There was also three men who claimed to be Ismail Mirza, the younger brother of Soltan Hoseyn. The most active of these was called Zainal Ebrahim, who appeared in Lahijan in 1728, at a time when the Russian empire had encamped his army in Gilan after their initial success in the war with the Safavid between 1722–1723. With a large army of mountaineers from Deylam, Zainal Ebrahim occupied Deylaman, Rankuh, and Masuleh and became a major threat to the interests of all the great players of the era: Tahmasp II, the Russians and the Ottomans alike.[13] The governor of Gilan defeated Zainal, however, the rebel soon recovered from this defeat. Raising a force of 5,000, he marched on Ardabil, where he defeated the Ottomans in a pitched battle and drove them out of the city. In Ardabil, he paid his respects to the tomb of his supposed forebear, Safi-ad-din Ardabili and collected an army of 12,000. With this army, he drove the remaining Ottomans forces out of Mughan and Ganja, but soon afterwards was killed in his camp by his local allies, allegedly on the instigation of the Russians.[12] The last pretender who claimed to be Ismail Mirza—and one who might have been genuine—appeared in Isfahan about 1732, after the city was liberated from Afghan occupation by Tahmasp II. He claimed to have escaped death with the help of a royal servant, but later had been captured and mutilated by a false Safi Mirza.[12] Tahmasp accepted Ismail Mirza, probably because recently he had found his own mother, who had been disguised as a servant, performing menial tasks in the harem.[14] However, Ismail Mirza was later accused of partaking in a court conspiracy to dethrone Tahmasp, and in turn was executed.[15]

Another spurious pretender who emerged during the later years of the Afghan period was one "Shahazadeh Mohammad Kharsavar", an opportunist mountebank who saw a chance to acquire power in the anarchy that his country had fallen into.[15] His epithet, Kharsavar or "Mule Rider", came from the fact that he habitually rode a saddled donkey.[16] Claiming to be a son (or by some accounts a brother) of Soltan Hoseyn, he convinced many of his compatriots in Baluchistan to pledge to him, even though he was a known figure in the area. He was eventually defeated by an Afghan army of 20,000 and had to flee to India by foot.[15]

Afsharid and Zand periods[edit]

During the later years of Nader Shah's reign, rebellious regions such as Dagestan and Azarbaijan attracted Safavid pretenders.[17] One of which called himself Sam Mirza (despite Soltan Hoseyn never having a son by this name.) This rebel attempted two rebellions, one in 1740 which led to a fast defeat, and the other mildly successful one in 1743, when a raise in taxes in northern Iranian provinces had caused an uproar.[18] He captured and killed the governor of Shirvan and took some towns in the nearby area. Nader Shah, worried by these developments handed a strong army over to his son, Morteza Mirza Afshar. This army crushed Sam Mirza's men in Shamakhi on 20 December 1743. Afterwards, Sam Mirza fled to Georgia.[18]

Legitimate pretenders[edit]

The Last Safavid pretender[edit]

Legacy[edit]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Perry 1979, p. 1.

- ^ Matthee 2019, p. 243.

- ^ a b Matthee 2015.

- ^ a b Axworthy 2006, p. 51.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 53.

- ^ Matthee 2019, p. 241.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Axworthy 2006, p. 66.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d e f Perry 1971, p. 60.

- ^ Siahpour 2018, p. 108.

- ^ a b c d Perry 1971, p. 61.

- ^ Rezazadeh Langaroudi 2001.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Perry 1971, p. 62.

- ^ Khazeni 2009, p. 28.

- ^ Avery 1991, p. 47.

- ^ a b Perry 1971, p. 63.

Bibliography[edit]

- Axworthy, Michael (2006). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1850437062.

- Khazeni, Arash (2009). Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran. Publications on the Near East. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295800752. OCLC 747411349.

- Matthee, Rudi (2019). Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000392876. OCLC 1274244049.

- Matthee, Rudi (2015). "SOLṬĀN ḤOSAYN". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Edition. Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation.

- Perry, J. R. (1971). "The Last Ṣafavids, 1722-1773". Iran. 9: 59–69. doi:10.2307/4300438.

- Perry, John R. (1979). Karim Khan Zand: A History of Iran, 1747-1779. Publications of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226660982.

- Rezazadeh Langaroudi, Reza (2001). "GĪLĀN vi. History in the 18th century". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Edition. Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation.

- Siahpour, Kashvad (2018). "مدعیان داخلی حکومت صفوی پس از سقوط اصفهان، مطالعه موردی: شورش صفی میرزا" [Claimants of Safavid throne after the fall of Isfahan, case study: Safi Mirza's rebellion]. Historical Studies (in Persian). 11: 103–121.