User:Ɱ/Briarcliff Manor article draft

{{Geobox|Settlement}}

Briarcliff Manor /ˈbraɪərklɪf/ is a suburban village in Westchester County, New York, less than 30 miles (48 km) north of New York City. It is geographically shared by the towns of Mount Pleasant and Ossining, and has the ZIP code 10510. The village is on the east bank of the Hudson River, and is served by the Scarborough station of the Metro-North Railroad's Hudson Line. Briarcliff Manor includes the communities of Scarborough and Chilmark.

The village motto is "A village between two rivers", reflecting Briarcliff Manor's location between the Hudson and Pocantico Rivers. Although the Pocantico is the primary boundary between Mount Pleasant and Ossining, since its incorporation the village has spread into Mount Pleasant. Briarcliff Manor, established and funded by Walter William Law during the 20th century, has grown from the 331 people required for village establishment to 7,867 in the 2010 census.

At the time of its settlement, the area was known as Whitson's Corners until the development of Briarcliff Farm and Manor during the 1890s. Briarcliff Manor was incorporated as a village in 1902. A section of the village, including buildings and homes covering 376 acres (152 ha), is part of the Scarborough Historic District and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. Briarcliff Manor celebrated its centennial on November 21, 2002.

History[edit]

Name[edit]

Briarcliff Manor derives from "Brier Cliff", a compound of the English words "brier"[nb 1] and "cliff". The name originated in Ireland as that of the family home of John David Ogilby, a professor of ecclesiastical history at the General Theological Seminary. Ogilby had named his New York summer home Brier Cliff after the family home in Ireland. In 1890, Walter Law bought James Stillman's 236-acre (96 ha) farm and named it Briarcliff Farms, later using the name Briarcliff for all his property. Law's friend, Andrew Carnegie, called him "The Laird of Briarcliff Manor"; since the title appealed to all concerned, the village was named "Briarcliff Manor".[1][2] The village (and its name) were approved by its residents in a September 12, 1902 referendum; the name prevailed over other suggestions, including "Sing Sing East".[nb 2][3] On November 21, 1902, the village of Briarcliff Manor was established.[2]

The village is also known by several other names. It is conversationally called "Briarcliff", and often erroneously written as "Briar Cliff Manor" (although historically there has been little distinction).[4][5][6] It is also known as "the Village of Briarcliff Manor".[7]

Prehistory[edit]

Briarcliff Manor has been inhabited by humans since the Archaic period, as Louis Brennan and other archaeologists discovered in the Scarborough neighborhood during the 1960s and 1970s. They found and dated oyster shells, stone tools and slings (most to the Archaic period of 8000 to 1000 BC).[2] In the precolonial era, the area of present-day Briarcliff Manor was inhabited by a band of the Wappinger tribes of Native Americans known as Sint Sincks (or "Sing Sings"). The tribe spoke coastal Munsee and called themselves Lenape ("the People").[2] They owned territory as far north as the Croton River; the Wappingers held land as far north as the Roeliff Jansen Kill, their boundary with the Mahican tribe.[8][9][10]

Early history[edit]

On August 4, 1685, Frederick Philipse purchased about 156,000 acres (630 km2) from the Sint Sincks, extending from Spuyten Duyvil Creek along the Hudson River to the Croton River.[11][12] In 1765, the Wappingers unsuccessfully attempted to sue the Philipse family for control of the land; their claim died out after around fifty tribespeople, organized into the Stockbridge Militia under Abraham Nimham and his father Daniel Nimham, were killed by British forces in the Battle of Kingsbridge during the American Revolutionary War.[13][14] The Philipses also lost their claim to the land because of the war; the family, which was Loyalist, had its property confiscated by the Commission on Forfeiture of the State of New York in 1779 and it was sold in 1784–85.[3][11] The area remained largely unsettled until after the Revolution; in 1693, fewer than twenty families lived in the 50,000-acre (200 km2) area of Westchester which included Briarcliff Manor.[2] It became known as Whitson's Corners for brothers John H., Richard and Reuben Whitson, who owned adjoining farms totaling 400 acres (160 ha) in the area.[15][12] In 1865, a one-room schoolhouse was built on land donated by John Whitson. The building (Whitson's Schoolhouse, District No. 6) became the first schoolhouse and church in the area and George A. Todd, Jr. was the first teacher and superintendent of the school.[8][16] In 1880 the Whitson's Corners station was added to the New York City & Northern Railroad train schedule,[17] and the first train arrived on December 13. A post office was established a year later; it was renamed the Briarcliff Manor Post Office in 1897.[11]

Progressive Era[edit]

After retiring as vice president of W. & J. Sloane, Walter Law moved with his family to the present Briarcliff Manor. He bought his first 236 acres (96 ha) with the James Stillman farm for $35,000 in 1890.[12] Law rapidly added to his property, buying about forty parcels in less than ten years; by 1900, he owned more than 5,000 acres (7.8 sq mi) of Westchester County.[17][18]

Law later established Briarcliff Farms, a large holding of Jersey dairy cattle. At its zenith, Law had 500 workers caring for more than 1,000 cattle, 500 pigs, 4,000 chickens, Thoroughbred horses, pheasants, peacocks and sheep.[15] Around the same time, he established the Briarcliff Table Water Company and the Briarcliff Greenhouses. The water company sold its products in five cities and had 250-foot (76 m) wells.[12] Briarcliff Farms was one of the first producers of certified milk in the U.S., and Law's Jerseys produced about 4,500 US quarts (4,300 litres) of milk daily.[19] His milk, cream, butter and kumyss was sent to New York City every night on the New York and Putnam Railroad.[20] Milk from Briarcliff Dairy won a gold medal at the 1900 Paris Exposition. Law's greenhouse space grew to 75,000 square feet (7,000 m2), and his roses earned up to $100,000 each year. As many as 8,000 roses were shipped from Briarcliff Greenhouses daily, most to New York City.[17] Law developed the village, establishing schools, churches, parks and the Briarcliff Lodge. His employees at Briarcliff Farms moved into the village, and Law held some of their mortgages. At the time, New York State required a population density of at least 300 per square mile as the first step towards incorporation as a village. A proposition was presented to the supervisors of Mount Pleasant and Ossining on October 8, 1902 that the area of 640 acres with a population of 331 be incorporated as the Village of Briarcliff Manor,[11] and the village was incorporated on November 21.[2][8]

At its 1902 opening, the Briarcliff Lodge was a premier resort hotel. The Tudor Revival-style building was surrounded by dairy barns and greenhouses (built by Law), and hosted guests including Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, Tallulah Bankhead, Johnny Weissmuller, Jimmy Walker, Babe Ruth, Edward S. Curtis,[21] Thomas Edison, George B. Cortelyou, Mary Pickford, F. W. Woolworth and J. P. Morgan.[1][22][23] The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace held its National Conference on International Problems and Relations at the Briarcliff Lodge from May 10–14, 1926.[24] The hotel declined during the 1930s but the lodge remained in use, housing the Edgewood Park School (1936–1954) and The King's College (1955–1994).[25] The original 1902 Briarcliff Lodge building burned to the ground on September 20, 2003, and contemporary portions of the lodge and other campus buildings were later demolished.[16]

The Briarcliff Manor Fire Department was founded on February 10, 1903 (succeeding the 1901 Briarcliff Steamer Company No. 1) by Frederick C. Messinger.[12] Its first fire engine was white, which Messinger thought more visible than the conventional red in a village without street lights, and the village's engines remain white. The department was reorganized in 1906 as the Briarcliff Fire Company, and a 1932 combination with the Scarborough Fire Company helped establish the Briarcliff Hook and Ladder Company in 1936. The first twenty-nine street lights, all electric, were installed in 1904, and Scarborough was incorporated into Briarcliff Manor in 1906. The Police Department was organized in 1908. The Village Municipal Building was built in 1913 at a cost of $20,000, and was opened on July 4, 1914. Currently housing several businesses, during the 1960s its cupola bell was moved to the front of the new firehouse.[26] The Public Library, in the Briarcliff Community Centre, was founded in 1910.[11] During World War I, 91 Briarcliff Manor residents served in the U.S. armed forces.[11]

Post-Progressive Era[edit]

Walter Law died on January 18, 1924. V. Everit Macy donated 265 acres (107 ha) to the Girl Scouts of the USA in 1925, which later became the Edith Macy Conference Center. The high school opened in 1928, and a section was added to the 1909 school building. A 1934 100-mile race in the village was sponsored by the Automobile Racing Club of America. During World War II, more than 340 of the village's 1,830 residents served in the U.S. armed forces.[7] A sufficient number of firefighters were serving that the village requested volunteers ages 16-18 to join the Briarcliff Manor Fire Department; at least nine served on active duty during the war. In May of 1946, an honorary dinner event was held for the returned veterans.[26] In the same year, the People's Caucus party, an organization which calls out interested residents for candidacy, was created.[7][27]

Briarcliff Manor celebrated its semicentennial celebration from October 10–12, 1952, publishing a book about the village and its history; that year, the Crossroads neighborhood of 84 houses was completed.[11] In 1953, Todd Elementary School opened to free space at the Law Park grade school for middle- and high-school students.[2] The Putnam Division was discontinued in 1958,[28] and the following year a library opened in the former train station. The village's first corporate facility (part of Philips Laboratory) opened in 1960. In 1964 the new Village Hall opened, replacing the Municipal Building. The present high school opened in 1971 to ease the large enrollment at the grade-school building.[2] Pace University bought Briarcliff College in 1977 as a satellite of the school's Pleasantville campus. The following year, the Scarborough School closed. In 1980, the Chilmark Club became a part of the village's Parks and Recreation Department; Pace University began leasing the middle-school building, and the middle school was moved to a portion of the new high-school building. Rotary International founded a local chapter the following year. In 1994, The King's College closed; the Briarcliff Lodge property reopened in 1998 as Northeastern Bible College. The grade-school building was demolished in 1996, and senior housing was built on its site the following year. In 1998, the high-school auditorium opened. On 16 September 1999, the Beech Hill Road bridge was destroyed by the rising Pocantico River during Hurricane Floyd.[29] The village celebrated its centennial in 2002, which involved numerous celebratory events.[27]

Since 2011, the village has been involved in an annexation proposal by the Town of Ossining. A petition was circulated in Ossining election districts 17 and 20, which was signed by about 20 percent of their residents.[30] During the week of October 14, 2013, the petition was filed with the Town of Ossining and the Village of Briarcliff Manor.[31] A public hearing, including both local boards, was held on December 12.[30] In March, the Briarcliff Manor board approved the proposal, while the Ossining town board rejected it. Briarcliff Manor has the option to refer the issue to the Appellate Division Court.[32]

Geography[edit]

Briarcliff Manor is 30 miles (48 km) north of Manhattan. As part of Westchester County, the village is part of the New York metropolitan area and the New York–Jersey City–White Plains, NY–NJ Metropolitan Division.[33] It is on the Hudson River, just north of the Tappan Zee Bridge and south of Croton Point (near the widest part of the river)[34] and just northwest of the county's center.[35] According to the 2010 United States Census Briarcliff Manor covers an area of 6.7 square miles (17 km2), of which 5.9 square miles (15 km2) is land and 0.8 square miles (2.1 km2) is water.[36] The village, which was incorporated with one square mile in 1902, has expanded primarily through annexation: of Scarborough in 1906 and from the town of Mount Pleasant in 1927.[12] It is in area code 914, with a ZIP code of 10510.[23]

Climate[edit]

The village is in a humid continental climate zone (Köppen climate classification: Dfa), with cold, snowy winters, hot, humid summers and four distinct seasons.[37] Its plant hardiness zone is 7a.[38] Summer high temperatures average in the lower 80s Fahrenheit (upper 20s Celsius), with lows average in the lower 60s F (upper 10s C).[39] Its highest recorded temperature was 100°F (38°C) in 1995, and its lowest was −10°F (−23°C) in 1979.[40]

| Climate data for Briarcliff Manor | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

73 (23) |

85 (29) |

95 (35) |

94 (34) |

94 (34) |

100 (38) |

100 (38) |

95 (35) |

87 (31) |

79 (26) |

73 (23) |

100 (38) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 34 (1) |

39 (4) |

47 (8) |

59 (15) |

69 (21) |

78 (26) |

82 (28) |

81 (27) |

73 (23) |

62 (17) |

51 (11) |

40 (4) |

60 (15) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 19 (−7) |

21 (−6) |

29 (−2) |

39 (4) |

49 (9) |

58 (14) |

63 (17) |

62 (17) |

54 (12) |

43 (6) |

35 (2) |

25 (−4) |

41 (5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −15 (−26) |

−10 (−23) |

0 (−18) |

14 (−10) |

30 (−1) |

38 (3) |

46 (8) |

39 (4) |

32 (0) |

20 (−7) |

11 (−12) |

−9 (−23) |

−15 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.58 (91) |

3.20 (81) |

4.22 (107) |

4.42 (112) |

4.35 (110) |

4.71 (120) |

4.81 (122) |

4.39 (112) |

4.57 (116) |

4.68 (119) |

4.38 (111) |

4.03 (102) |

51.34 (1,303) |

| Source: The Weather Channel[40] | |||||||||||||

Neighborhoods[edit]

The village is home to neighborhoods, business and residential areas, including the central business district, the hamlets of Scarborough and Chilmark and residential areas Central Briarcliff West, the Tree Streets and the Crossroads. Scarborough is an unincorporated district on the Hudson, divided between Briarcliff Manor and the village of Ossining, with a post office and a station on the Metro-North Hudson Line. Unlike most of Briarcliff Manor, Scarborough is within the Ossining Union Free School District. During the 17th century, Scarborough became one of the first trading posts for the Dutch on the Hudson. During the early 20th century, the Astor, Rockefeller and Vanderbilt families entertained guests on their river-view country estates in the Scarborough area. The Scarborough Historic District, including the Scarborough Presbyterian Church, is on the National Register of Historic Places. Across the street from the church is Sparta Cemetery, with the graves of local Revolutionary War veterans and the Leatherman. Scarborough was incorporated into Briarcliff Manor in 1906.[2] A notable building is the Beechwood Estate, built around 1780 and considered one of the finest examples of Federal architecture in Westchester County.[8] William Creighton, founder of St. Mary's Episcopal Church, named the house "Beechwood" after he purchased it in 1836.[11] Part of the estate became the Scarborough Country Day School, originally founded in 1913[41] and closed during the early 1980s. Holly Hill is also part of the district. Hubert Rogers, a New York City attorney, had the house designed by William Adams Delano and named it Weskora. After his death Brooke Astor purchased the estate, renaming it Holly Hill for its holly trees.[2]

Chilmark (also known as Chilmark Park) is an unincorporated residential community of about 300 acres (120 ha), established in 1925, in northern Briarcliff Manor. The neighborhood was designed with Underhill Road as its main thoroughfare, running north-south.[42] It was named after the village of Chilmark, England, located near the home of Thomas Macy (an ancestor of Valentine Everit Macy), who arrived in the colonies in 1635. The area is culturally significant for its association with the Macy family, whose members were active in New York and Westchester County during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Valentine Everit Macy and his wife, Edith Carpenter Macy, founded the community and aided in its development; Macy purchased several small family farms in present Chilmark in 1897.[42] In 1925, Macy donated 265 acres (107 ha) on Old Chappaqua Road for the Edith Macy Conference Center, a conference and training facility owned and operated by the Girl Scouts of the USA which was the first national Girl Scout camp.[17] The Briarcliff Recreation Center was the private Chilmark Club until the 1970s, when the village purchased the land for a recreation center and adjoining park. The Chilmark Estate (Macy’s residence in the neighborhood) is a Tudor-style stone and stucco mansion with a nine-hole golf course, which was built in 1896. The neighborhood hosts Briarcliff's only non-Christian house of worship, the Conservative temple Congregation Sons of Israel.[8]

Chilmark features landscaped, winding roads designed to blend with the topography, access to transportation (including a commuter rail line and a highway and homes built in revival styles echoing Tudor and Gothic architecture; it is architecturally significant as an example of early-20th-century suburban design.[42] During the 1920s Macy’s son, V.E. Macy Jr., founded the Chilmark Park Realty Corporation to sell land parcels. When he began marketing the area, he renovated or demolished existing homes to lend an air of development and built a private 8.3-acre (3.4 ha) country club for use by Chilmark residents. The village of Briarcliff Manor later purchased the site, and operates it as Chilmark Park. To denote its development as an exclusive neighborhood, Macy planted distinctive shade trees along Underhill Road. Since its founding additional homes have been built in Chilmark, expanding the development beyond its original 300 acres; it presently comprises Underhill Road and the streets immediately adjacent to it.[42]

The central business district, also known as the Village Center or East End, is located on Briarcliff Manor's main street on Pleasantville Road.[43] It is home to the village hall, a pocket park and a number of businesses.[44] Farther south along the road is the Walter W. Law Memorial Park, and southeast along the road are the three schools of the Briarcliff Manor School District. The Village Center contains a number of pre-Revolutionary War houses, including the Whitson House, built during the 1770s and the former home of Richard Whitson (one of the Whitson brothers, after whom Whitson's Corners was named); Buckhout House, also dating to the 1770s and named for the family who lived there for over a century and the oldest, Century Homestead, dating to about 1767 and first owned by Reuben Whitson.[8] The Washburn House, another pre-Revolutionary house, was sold by the Commission on Forfeiture to Joseph Washburn in 1775.[11]

Central Briarcliff West is a neighborhood which has a number of mansions built by 20th-century millionaires who stayed at the Briarcliff Lodge and later built estates in the area. The Briarcliff Lodge was built in 1902 by Walter Law on the highest point of his estate. Within a few years it became a luxury resort hotel, hosting many celebrity guests. The lodge had a large Roman-style pool; when it was built in 1912, it was the largest outdoor pool in the world[3] and was used for the 1924 Olympic trials.[2] The Briarcliff Lodge was noted for its cuisine (including Briarcliff dairy and table water), a golf course, fifteen tennis courts, a music room, theatre, indoor swimming pool, casino, library, stable, repair shops and a fleet of Fiat automobiles.[17] The lodge later anchored the Edgewood Park School for Girls campus and The King's College, and was destroyed in a fire shortly before its scheduled demolition in 2003.[18] Other historic estates in the neighborhood include the Law Family Homes (built in 1902 for Walter Law's children) and Law's home, the Manor House. The three estates for his children are Six Gables, Mt. Vernon and Hillcrest. The modernist Vanderlip-Street house, designed by Wallace Harrison for Frank A. Vanderlip (who built it for his daughter and son-in-law) was one of the first contemporary-style homes in Westchester. Ashridge, a large Greek Revival estate, was built around 1825.[8]

Smaller neighborhoods in Briarcliff include the Tree Streets and the Crossroads. The Tree Streets is a network of streets named after regional trees, including Satinwood Lane, Larch Road and Oak Road. Some of the village's oldest houses (constructed during a 1930s building boom) are on these streets, circling Jackson Park and near Todd Elementary School.[8] The Crossroads is a group of 84 houses on streets named after local World War II veterans, including Schrade Road, Hazelton Circle, Matthes Road and Dunn Lane. It expanded at the end of World War II to provide affordable housing to returning veterans, and was completed in 1952.[2][8][45]

Demographics[edit]

Historical[edit]

Historically, Briarcliff Manor's racial composition has not changed significantly. The village has seen a decrease in its non-Hispanic white population to 66 percent, down from 92 percent in 1990. The mid- to late-20th century saw an increase in the African-American population from 2.1 to 3.4 percent.[46][47]

The village has experienced significant population growth, with it and neighboring communities undergoing more rapid growth than Westchester County overall. The period from 1950 to 1970 saw the greatest increase in population, with growth leveling off since then.[46]

Modern[edit]

Briarcliff Manor is primarily noncommercial, with over 80 percent of village land residential.[2] In the 2010 United States Census there were 7,867 people, 2,647 households and 2,037 families living in 2,753 housing units. Hispanic and Latino Americans comprised 5.3 percent of the population. Of the 2,647 households, 39.7 percent had children under age 18 living with them; 68.5 percent were married couples living together, 6.6 percent were headed by women, 1.9 percent were single males and 23 percent were non-families. Twenty-one percent of all households were individuals, with 14.1 percent age 65 or older. Average household size was 2.71; average family size was 3.16, with a median age of 43.4 years.[48]

The village's population density was 1,319.5 inhabitants per square mile (509.5/km2). In 2010, its racial composition was 86.4 percent white, 3.4 percent African American, 0.1 percent Native American, 6.9 percent Asian and 2.0 percent from two (or more) races; 25.6 percent of the population was under age 18.[47]

Median household income was $169,310, and median family income was $219,063. Males had a median income of $169,118, with $100,039 for females; per capita income was $81,465. About 4.3 percent of families and 4.8 percent of the overall population were below the poverty line, with the percentages rising to 5.6 percent for those under 18 and 6.4 percent for those 65 or over.[49]

| Population growth in Briarcliff Manor since 1902 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1902 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 |

| Population | 331 | 950 | 1,027 | 1,794 | 1,830 | 2,494 | 5,105 | 6,521 | 7,115 | 7,070 | 7,696 | 7,867 |

| 1902 to 1940[3] • 1950 to 2000[46] • 2010[48]

| ||||||||||||

Economy[edit]

| Employment by industry, 2000[46] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Industry | Employment | % of Total |

| Education, Health, Social Services | 832 | 24.9% |

| Professional, Scientific, Mgmt., Admin., Waste Mgmt. | 716 | 21.4% |

| Finance, Real Estate, Rental/Leasing | 590 | 17.7% |

| Trade | 333 | 9.9% |

| Manufacturing | 206 | 6.2% |

| Information | 199 | 6.0% |

| Other services | 176 | 5.3% |

| Construction | 124 | 3.7% |

| Arts, Entertainment, Recreation, Food Services | 116 | 3.5% |

| Transportation, utilities | 40 | 1.2% |

| Agriculture and resource-based | 8 | 0.2% |

| Total | 3,340 | 100% |

About five percent of Briarcliff Manor's land is occupied by businesses. The village has three retail business areas, a general (non-retail) business area and scattered office buildings and laboratories. The village’s principal retail district is along Pleasantville and North State Roads.[46]

The central business district has primarily retailers such as restaurants, cafes, small food markets and specialty shops. The North State Road business district has a supermarket, a bank, a gas station and a mixture of retail stores, and the other retail areas have national and local stores. The village has small offices and larger offices for the regional (or national) market, including Sony Electronics, Wüsthof and Philips Research North America; the latter is headquartered in Briarcliff Manor.[50][46]

The village economy depends on education, health care and social services. Of the population aged 16 and older, 63 percent are in the labor force; 33 percent of those employed work outside Westchester County. About 13 percent of workers live and work in the village, and the average commute is 37.1 minutes.[46] Briarcliff Manor has a number of wealthy residents, and was rated 19th on CNN Money's 25 Top-Earning Towns in the U.S.[51] An assessment by financial news corporation 24/7 Wall St., using data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey from 2006 to 2010, rated the village's school district the fifth-wealthiest in the United States and the third-wealthiest in New York.[52]

In 2004, the top five employers in Briarcliff Manor were the Briarcliff Manor Union Free School District, Philips Laboratories, Trump National Golf Club, the Clear View School and engineering firm Charles H. Sells. Other large employers are USI Holdings (a publicly-traded insurer headquartered in the village), Atria Briarcliff Manor, Pace University and the village (which employs 81 people).[46]

Arts and culture[edit]

The village symbol is the pink Briarcliff rose, similar to a rose grown in the Briarcliff Greenhouses (a more brightly-colored offshoot of the American Beauty rose).[8] Since 2006, the Briarcliff Rose has been used on village street signs.[53] Briarcliff Manor has groups in several Scouting organizations, including Cub Scout Pack 6 and Boy Scout Troop 18.[54][55] The village's first Boy Scout troop was Troop 1 Briarcliff, founded before 1919. Sources cite Bill Buffman as the first Scoutmaster and John Hersey as the troop's first Eagle Scout. The first Girl Scout troop in the village was founded in 1917 by Louise Miller and Mrs. Alfred Jones, and the first Brownie troop was founded in 1929.[2][45]

The Briarcliff Manor Community Bonfire is a winter holiday event at Law Park, hosted by the village and the Briarcliff Friends of the Arts, involving live music (primarily seasonal and holiday songs), refreshments and craft projects for children.[56] Another annual community event is the Memorial Day parade, a tradition in Briarcliff Manor for more than fifty years.[57] Before the parade begins, the Municipal Building's bell is rung to commemorate firefighters who have died in the previous year.[26]

Historical society[edit]

Briarcliff Manor maintains strong ties to its history and traditions. In June 1974, the Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough Historical Society was founded. It is located in the Eileen O'Connor Weber Historical Center, established on March 21, 2010 as part of the expanded Briarcliff Library. The Historical Society published a 1977 village history (A Village Between Two Rivers: Briarcliff Manor) marking the 75th anniversary of the village.[2]

The society helped organize several events for the village’s 2002 centennial celebration, including the Centennial Variety Show at the Briarcliff High School auditorium in a sold-out two-night run on April 26–27, 2002.[3] The two-act show consisted of interpretations of village life by village organizations and a revue of Briarcliff Manor history in skits and songs.[27] Other society-sponsored events have included tours of homes and churches, bus tours, Hudson River cruises on historic boats such as the M/V Commander (built in 1917 and listed on the national and state registers of historic places), dances, antique-car exhibits, day trips to historic points of interest, art exhibits and events with authors and elected officials.[58]

Literature and film[edit]

Briarcliff Manor has been the subject, inspiration or location for literature and films. Much of James Patterson's 2005 novel, Honeymoon, is set in the village (where Patterson is a part-year resident).[59] Sharon Anne Salvato's Briarcliff Manor takes place on the fictional estate of Briarcliff Manor, and the novel was published by Stein and Day in the village.[60] The pilot episode of Saturday Night Live was filmed in the central business district, where Briarcliff Manor Pharmacy, Briarcliff Wines & Liquors and Briarcliff Hardware are the backdrop for the "Show Us Your Guns" sketch.[61] In Pan Am, the Sleepy Hollow Country Club was the setting for much of the series' third episode.[62][63]

Films shot in the village include The Seven Sisters, House of Dark Shadows, Savages, Super Troopers and American Gangster. The Seven Sisters, a 1915 production, was filmed at the Briarcliff Lodge.[64] The 1970 House of Dark Shadows and the 1972 Merchant Ivory film Savages were filmed at the Beechwood Estate in Scarborough.[65][66] Super Troopers, released in 2001, was partially filmed on the Taconic State Parkway from Poughkeepsie to Briarcliff Manor.[67] American Gangster, released in 2007, includes scenes filmed at two village houses.[68]

Historic sites[edit]

Briarcliff Manor is home to a number of historic buildings and districts. Buildings on the National Register of Historic Places include All Saints' Episcopal Church (added March 2, 2002), Carrie Chapman Catt's house Juniper Ledge (added March 4, 2006)[69][70] and several structures in the 376-acre Scarborough Historic District (added September 7, 1984).[71][72] Part of the Old Croton Aqueduct State Historic Park, controlled by the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, lies within the village.[73] The Old Croton Aqueduct is on the National Register and is a National Historic Landmark.[71][74]

Although Carrie Chapman Catt's home Juniper Ledge is within Briarcliff Manor's postal boundaries, the property is located within the municipal boundaries of the town of New Castle. Village resident Carmino Ravosa has sparked the home's preservation by researching and initiating the nomination of Juniper Ledge to the National Register.[69][75][76]

Houses of worship[edit]

Briarcliff Manor is home to seven Christian churches and two synagogues; three (Holy Innocents Anglican Church, Saint Mary's Episcopal Church and Scarborough Presbyterian Church) are in Scarborough. Other churches in the village are All Saints' Episcopal Church, St. Theresa's Catholic Church, Faith Lutheran Brethren Church and Briarcliff Congregational Church (United Church of Christ). Congregation Sons of Israel, a Conservative synagogue, is in Chilmark. Another Jewish house of worship, Chabad Lubavitch of Briarcliff Manor & Ossining, is at Orchard Road in Briarcliff Manor.[8][77]

Saint Mary's Episcopal Church, founded in 1839 by William Creighton as Saint Mary's Church, Beechwood, is Briarcliff Manor's oldest church; it was reincorporated in 1945 as Saint Mary's Church of Scarborough.[11] The church is in near-original condition, with a design based on the 14th-century Gothic St. Mary's parish church in Scarborough, England and the only church with a complete set of William Jay Bolton stained-glass windows.[8] The church, built in 1851, is part of the Scarborough Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places. The 200-acre-plus (81 ha) Sleepy Hollow Country Club surrounds the church grounds on three sides.[78] Notable parishoners included Commodore Matthew C. Perry and Washington Irving. Irving, author of "Rip Van Winkle" and "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow", brought the ivy surrounding the church from Abbotsford (home of Walter Scott).[12]

Scarborough Presbyterian Church, given to the community by Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt Shepard and her husband (who lived on the nearby Woodlea estate), was the first church in the United States with an electric organ.[8] Built in 1895 and designed by Augustus Haydel (a nephew of Stanford White) and Shepard (a nephew of Elliot Shepard)—who designed the 1899 Fabbri Mansion in Manhattan—the 3-acre (1.2 ha) church property is also part of the Scarborough Historic District.[78][79]

All Saints' Episcopal Church is a stone church also on the National Register of Historic Places. It was founded in 1854 by John David Ogilby, whose summer estate and family home in Ireland were the namesakes of Briarcliff Manor. The Gothic Revival church, built on Ogilby's summer estate,[71] was designed by Richard Upjohn and modeled on Saint Andrew's in Bemerton, England.[2][80] The church, with an 1883 Stick Style rectory and 1904 Arts and Crafts-style parish hall, is an example of the modest English Gothic parish church popular in the region during the mid-19th century.[80]

The parish of St. Theresa's Catholic Church was established in 1926 with thirty-six families, and the present church was dedicated on September 23, 1928.[11][81] The Rectory of the church is one of the three houses belonging to the Whitson brothers.[16]

Faith Lutheran Brethren Church had its 1959 beginning in a white chapel in Scarsdale. Its congregation then sold the chapel and moved to its 2-acre (0.81 ha) site in Briarcliff Manor. The church, built largely through volunteer labor by the congregation's twelve families, held its first service on October 8, 1967. A nursery-school program, the Little School, began in 1972 and the church sponsors women's and youth groups.[7]

Briarcliff Congregational Church, built in 1896, has windows by Louis Comfort Tiffany, William Willet, J&R Lamb Studios, Hardman & Co. and Woodhaven.[8] The church began in a small, one-room schoolhouse (known as the "white school"), built around 1865 and used as a school, a religious school and a house of worship for up to 60 people. In 1896, George A. Todd Jr. asked Walter Law to support the construction of a new church. Law donated the church land, making his new church a Congregational one so the entire community (regardless of religious background) could attend. The nave and a Norman-style tower were built first, in an English-parish style with Gothic windows. When the congregation outgrew the church, Law funded a northern section (including transepts and apse) which was dedicated in 1905. He donated the church organ (replacing it in 1924), four Tiffany windows and the manse across the street.[17]

Congregation Sons of Israel, self-described as egalitarian Conservative, is the only synagogue in Briarcliff Manor.[82] The congregation was formed in 1891 by eleven men in Ossining, and until 1902 services were held in homes and stores. That year, the congregation (now twenty-three families) purchased a building on Durston Avenue; the Jewish Cemetery, established in 1900 on Dale Avenue, is still in use. In 1920 the synagogue, numbering forty-five families, established a religious school. After outgrowing its facilities, it purchased a site on Waller Avenue and completed a new synagogue in 1922. During the 1950s the congregation purchased the eleven-acre Mead Farm on Pleasantville Road, which it has used since 1960.[7]

Sports[edit]

Briarcliff High School offers intramural sports and fields junior varsity and varsity teams in sixteen sports as the Briarcliff Bears. Pace University fields fourteen intercollegiate varsity sports teams, and the Setters play at the Division II level. The school is also affiliated with the Northeast-10 Conference and the Eastern College Athletic Conference.[83]

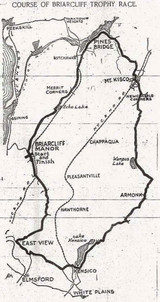

Briarcliff Manor has a history of auto racing. The First American International Road Race, sponsored by the village, centered around it.[2][84] The prize, the Briarcliff Trophy valued at over $10,000, was presented by Walter Law.[11] The race began at 4:45 a.m. on April 24, 1908, ending at the village grandstand.[85][86] The winner, Arthur Strang in an Isotta Fraschini, covered the 240 miles (390 km) in five hours and fourteen minutes.[87][11][84] More than 300,000 people watched the race, and the village had more than 100,000 visitors that day.[2]

On November 12, 1934, The Automobile Racing Club of America held another road race in Briarcliff Manor. The 100-mile (160 km) race was won by Langdon Quimby, driving a Willys 77, in a time of two hours and seven minutes. The race was held again on June 23, 1935; Quimby won again, four minutes faster than the previous year.[2] In 2008, the village commemorated the first race's centennial in a parade featuring about 60 antique cars.[87]

Parks and recreation[edit]

Briarcliff Manor has a number of recreational facilities and parks, all of which are accessible by the public. The Village Library houses the Recreation Department, which maintains the village's facilities. The following are available to Briarcliff Manor residents:[88]

- The 12-mile (19 km) Briarcliff-Peekskill Trailway runs from the village to the Blue Mountain Reservation in Peekskill. The parkland was acquired for use by the Briarcliff-Peekskill Parkway (now part of New York State Route 9A); the parkway later changed course, freeing the land for trail use.[89]

- Chilmark Park, 8.3 acres (3.4 ha) on Macy Road and formerly the Chilmark Country Club. The park has six tennis courts (two clay, two all-weather and two green clay), a half-court basketball court, a soccer field, a baseball-softball field and a playground. Renovation of the athletic fields and basketball court and the addition of a restroom are planned.

- The Hardscrabble Wilderness Area is a 235-acre (95 ha) network of wilderness trails.[90]

- The 4.76-acre (1.93 ha) Jackson Road Park, dedicated in 1975, features two half-court basketball courts: one with a standard 10-foot (3.0 m) rim and one with a 9-foot (2.7 m) rim for younger players. The playground was renovated in 2005. About half the park is undeveloped wetlands.

- The one-mile Kate Kennard Trail, named for the late daughter of a former mayor, was dedicated in 1988. It begins on Long Hill West, west of the Aspinwall Road intersection.

- Lynn McCrum Field, named for Briarcliff Manor's second village manager, was dedicated in June 1999.[2] The field, at the corner of Chappaqua Road and Route 9A, has a multipurpose playing field for baseball, softball and soccer, parking for 50 cars and a utility building with restrooms.

- Neighborhood Park, dedicated in 1954 and augmented in 1958 and 1964, is five acres at the corner of Whitson and Fuller Roads adjacent to Schrade Road. The Whitson Road side of the park has a youth baseball field; a basketball court and playground are accessible from the Schrade Road entrance.

- Nichols Nature Area, accessible from Nichols Place, is a steeply-sloped 3.8-acre site acquired in 1973 as part of a residential subdivision.

- The Old Croton Aqueduct State Historic Park, running along the Old Croton Aqueduct, crosses the village between Broadway and the Hudson River. Its trail, following the aqueduct from Croton to New York City, is a popular bicycling and running path maintained by New York State. Access from the village is from Scarborough Road north of the Scarborough Fire Station.

- Pine Road Park, an undeveloped 66-acre parcel acquired in 1948 and augmented in 1963, is located between Pine Road and Long Hill Road East.

- The 70.9-acre (28.7 ha) Pocantico Park, Briarcliff Manor's largest park, was acquired in 1948 and augmented in 1963, 1964 and 1967. Abutting the Pocantico River, it is home to a large number and variety of regional fauna and has marked hiking trails.[8]

- The Recreation Center, purchased by the village in 1980, is the former Chilmark Country Club clubhouse and provides seasonal indoor recreation. Community organizations using the center include the Briarcliff Manor Garden Club, the Senior Citizens Club and the Max Pavey Chess Club.[91]

- Scarborough Park, a six-acre, 97-year-old park near the Scarborough train station, has a view of the Hudson. The village is pursuing grant funding to further develop the site.[18]

- The 2,400-square-foot (220 m2) Village Youth Center, near the central business district, has a deck, a patio and a lighted outdoor basketball court. It also provides an indoor facility for community programs and activities.[92]

- Walter W. Law Memorial Park (originally Liberty Park),[7] in the center of the village on Pleasantville Road, is a seven-acre park which was donated to the village by Law in 1904.[12] The village pool, added in July 1927 at a cost of $8,641, has a 120-by-75-foot (37 m × 23 m) main pool and a 30-foot-diameter (9.1 m) wading pool;[12] it was Westchester's first public swimming pool.[2] A two-story bathhouse and pavilion was completed in 2001 as part of a rehabilitation project, which included paved walkways and a veterans' memorial.[3] The park was rededicated on Veterans Day 2001.[8] It has four lighted tennis courts: three clay and one all-weather. The pond was used for ice skating and hockey until the village bought a temporary rink for one of the tennis courts; the shallow rink freezes days earlier than the pond, and the tennis court lighting system allows easier skating at night.[93] Adjacent to the tennis courts is a playground. Two platform tennis courts are north of the park, and the Briarcliff Manor Public Library is on its eastern edge.

- The library, part of the Westchester Library System,[46] was founded and sponsored in 1914 by the Briarcliff Community Club and registered with New York State in 1921. In 1928 the Community Club property was sold; the library was housed in several locations for the next 30 years, until its present home opened on January 20, 1959.[16] It became a public library in 1964. The library is staffed by a director, 2+3⁄4 full-time and eight part-time employees, including reference and youth librarians. It is governed by a seven-member board, with liaison to the village board. Services include computer classes, book-discussion groups, young-adult programs, a children's room and a local-history collection. Library spending comprises about four percent of the village budget. A $4 million bond resolution was passed in 2006 for a two-story, 6,600-square-foot addition, which opened March 8, 2009.[46] The original library will be renovated as the Briarcliff Manor Community Center.[94]

- The Westchester County Bike Trail (also known as the North County Trailway) is a network of accessible trails criss-crossing woods, towns and highways. One highlight is the New Croton Reservoir and its rail bridge. Trail access from the village is behind the library, off Pleasantville Road. The trail extends north (primarily along Route 100) to Baldwin Place in Somers, and south along Route 9A to Eastview in Mount Pleasant.[46][95]

Although there are no public golf courses in Briarcliff Manor, the village has two large country clubs: Sleepy Hollow Country Club in Scarborough (founded in 1895) and Trump National Golf Club, owned by Donald Trump.[96] The Trump property has been home to several golf clubs since the early 20th century, including Briarcliff Golf Club, Briar Hills Country Club and Briar Hall Country Club. The main building of Sleepy Hollow Country Club was Woodlea, the 140-room Renaissance Revival mansion of Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt Shepard and her husband. The building, with Beaux-Arts and Georgian Revival features, was designed by Stanford White and built during the early 1890s.[8][18] In 1910, Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt Shepard sold the estate to Frank A. Vanderlip, who (with his friends John Jacob Astor, Cornelius Vanderbilt, William Rockefeller, James Stillman, Harrison Williams, V. Everit Macy, Edward Harden and Oliver Harriman, father of J. Borden Harriman) converted it into a country club;[97] Charles B. Macdonald designed its golf course.[2]

Government[edit]

| Briarcliff Manor | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crime rates (2007-2012) | ||||||

| Crime type | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

| Homicide: | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Robbery: | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Aggravated assault: | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total violent crime: | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Burglary: | 12 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 4 |

| Larceny-theft: | 35 | 29 | 27 | 15 | 22 | 10 |

| Motor vehicle theft: | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Arson: | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total property crime: | 51 | 36 | 28 | 18 | 30 | 14 |

| Sources: FBI 2012 UCR data Newsday | ||||||

The head of village government is Mayor William J. Vescio, a former village trustee who was elected mayor in 2005.[98][99] The village government consists of a mayor and four trustees, elected at-large to two-year terms. A full-time, appointed village manager handles day-to-day community affairs.[100] Briarcliff Manor's government is seated at the village hall, which houses the Justice Court and offices for the mayor and village manager.[101][102][103] As of February 2014[update], there are 5,531 registered voters in Briarcliff Manor.[104]

In the New York State Legislature, the western portion of Briarcliff Manor (in Ossining) is represented by Democrat Sandy Galef for the New York State Assembly's 95th District, while the eastern part (in Mount Pleasant) is represented by Democrat Thomas Abinanti for the Assembly's 92nd District.[105][106] Democrat David Carlucci represents the Ossining portion of the village for the New York Senate's 38th District, and Republican Gregory Ball represents the Mount Pleasant end of the village in in the Senate's 40th District.[107][108] In Congress, the village is represented by Democrats Nita Lowey in the House of Representatives from New York's 17th District and Kirsten Gillibrand and Chuck Schumer in the Senate.[109]

Crime[edit]

The Briarcliff Manor police force was founded by Edward Cashman, a one-person force who covered his beat on foot and by bicycle.[12] During the World Wars the crime rate was low, and village police work primarily involved rounding up animals (as the constabulary had done since before the Revolution). Most other cases were traffic violations, due to the village's size and parkway access. During the 1980s (as in the 1940s), the police blotter primarily consisted of accidents and traffic violations on the four major roads traversing the village; a 1939 village history asserted that "Briarcliff has never had a serious crime".[12] Burglaries have been primarily residential, and murder is rare. In 1989, when the police force considered replacing its .38 six-shot revolvers with semiautomatic 9mm pistols, opinion was divided; village officials could not remember when an officer last fired a gun on duty.[2]

In its study of 2012 FBI Uniform Crime Reports, national realtor Movoto LLC assessed Briarcliff Manor as the second-safest municipality in New York, with the second-lowest crime rate in the state. According to the FBI reports, the village had no reported violent crimes in 2012 and a resident had a 1-in-569 chance of being a crime victim.[110][111]

Education[edit]

Primary and secondary schools[edit]

The village is home to the Briarcliff Manor School District, which serves over 1,000 students and includes Todd Elementary School, Briarcliff Middle School and Briarcliff High School.[8] The district is noted for its annual high-school musicals.[112] The elementary school (opened in 1953) is named after George A. Todd, Jr.,[8] who was the village's first teacher, first superintendent and taught for over 40 years.[8] The middle school became a Blue Ribbon School in 2005,[113] and the district is part of a Board of Cooperative Educational Services program in Yorktown Heights (the Tech Center at Yorktown).[114]

Higher education[edit]

Briarcliff Manor has been the location for several colleges. Briarcliff Junior College was founded in 1942 near Briarcliff Congregational Church. Among its trustees were Howard Deering Johnson, Norman Cousins, Carl Carmer, Thomas K. Finletter, William Zorach, Eduard C. Lindeman and Lyman Bryson. Ordway Tead was chairman of the board of trustees, and his wife Clara was the college's first president. The school gradually improved its academic scope and standing, and was registered with the State Education Department and accredited by the Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools in 1944. In 1951, the Board of Regents authorized the college to grant Associate of Arts and Associate of Applied Science degrees. The following year, the Army Map Service selected the college as the only one in the country for professional training in cartography. The school library, which had 5,500 volumes in 1942, expanded to about 20,000 in 1960. In 1977 Pace University bought the Spanish Renaissance-style school building next to Law Park, incorporating it into its Pleasantville campus (as the Pace University Village Center) after leasing it for many years. During Pace's lease, the building housed the Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough Historic Society and the Village Youth Center.[2] The King's College was located on the Briarcliff Lodge property from 1955 to 1994, using the lodge building and building dormitories and academic buildings.[2]

Media[edit]

Briarcliff Farms operated a printing press and office during the early 20th century, producing Briarcliff Farms, the Briarcliff Bulletin in 1900, The Briarcliff Outlook in 1903 and The Briarcliff Once a Week in 1908 (all edited by Arthur Emerson).[11] The Briarcliff Community Club later printed Community Notes. Later papers include The Briarcliff Forum (founded in 1926) and the 1930s Briarcliff Weekly.[12] Briarcliff Manor is the city of license of WXPK, and other media outlets include the Briarcliff Daily Voice, The Journal News, News 12, the Ossining-Briarcliff Gazette, Patch Media and the River Journal.[115][116]

Infrastructure[edit]

The Briarcliff Manor Police Department (VBM PD) and the volunteer Briarcliff Manor Fire Department (BMFD) are stationed at the village hall.[117] The Briarcliff Manor Ambulance Corps, in the Fire Department, provides emergency medical transport with two ambulances.[118]

The Briarcliff Manor Department of Public Works supplies water from the Catskill Aqueduct,[119] maintains the sewer system, village vehicles, roads and grounds, operates a recycling center and removes snow.[120] In 2012 the village tied for fourth place (out of 48 Westchester municipalities) in the percentage of recycled waste (71 percent, above the county average of 52 percent).[121] The department, primarily rooted in the 1941 sale of Walter Law's Briarcliff Table Water Company, began with a state-mandated street commissioner. The commissioner in 1914 was Arthur Brown; asked by village officials if he needed an automobile, Brown replied that he preferred a horse but would use an automobile if the village purchased it (it did not). The department has about thirty vehicles and employs twenty-nine men.[7][122]

The village's transportation system includes highways, streets and a rail line; its low population density favors automobiles. Briarcliff Manor is accessible by the controlled-access Taconic State Parkway; it can also be reached by U.S. Route 9, New York State Route 9A and New York State Route 100, which traverse the village north to south. East-west travel is more difficult; Long Hill Road, Pine Rood, Elm Road and Scarborough Rood are narrow, winding and hilly.[46]

Briarcliff Manor has 64 roads, with a total length of about 30 miles (48 km). Twelve are named after trees, eleven after local residents and eight after veterans. The village's oldest existing road is Washburn Road, on which is the 1767 Century Homestead. The longest road in the village, at 3 miles (4.8 km), is Pleasantville Road; the shortest is Pine Court, 175 feet (53 m).[11] According to the National Bridge Inventory, Briarcliff Manor has 15 bridges, with estimated daily traffic at 204,000 vehicles.[123]

The Metro-North Railroad Hudson Line's Scarborough station offers direct service to New York's Grand Central Terminal, and is the primary public transport to the city. About 750 commuters board southbound trains during the morning rush hour, most driving to the station.[46] Westchester County's Bee-Line Bus System provides service to White Plains, Tarrytown and Port Chester along Routes 9 and 9A.[46]

Rail transportation in the village began in 1880 with the small Whitson's Station on the New York City & Northern Railroad (later the New York and Putnam Railroad); the station was rebuilt by Walter Law in 1906 in the style of his Briarcliff Lodge,[16] with Mission style furniture and rugs. The old station was moved to Millwood, New York in 1909 to become its station;[2] it fell out of use and was demolished May 9, 2012, although plans exist for the construction of a replica.[124] Law's Briarcliff station became the public library in 1958.[2]

Notable residents[edit]

Historic[edit]

Briarcliff Manor was historically notable for its wealthy estate-owning families, including the Rockefellers, Astors, and Macys. Many of the extended Rockefeller family lived in and around the neighboring area of Pocantico Hills, and William Rockefeller (brother of John D. Rockefeller) lived for some time at the Edgehill estate in the village.[2][125] Businessman William Henry Aspinwall lived in Scarborough, and was sent to England during the American Civil War to prevent the construction of Confederate ironclad warships. He was involved in the Panama Canal; Panama's second-largest city (now known as Colón) was named Aspinwall after him by emigrants from the U.S., and Aspinwall Road in Scarborough was later named after him. John Lorimer Worden, a U.S. Navy rear admiral who commanded the USS Monitor against the CSS Virginia during the Battle of Hampton Roads, was born in Scarborough.[2][126][127][41] Carrie Chapman Catt, a pioneer in the campaign for women's suffrage (president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association and founder of the League of Women Voters and the International Alliance of Women),[128] lived at Juniper Ledge during the 1920s.[70] William J. Burns was the penultimate director of the Bureau of Investigation; his successor, J. Edgar Hoover, transformed the agency into the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Burns established a private-investigation service, the William J. Burns International Detective Agency, and his family moved to a house named Shadowbrook in 1917.[2]

Marian Cruger Coffin, a landscape architect, was born in Scarborough.[129] Brooke Astor, a philanthropist, socialite and member of the Astor family, lived in Briarcliff Manor for much of her life.[130] Children's author C.B. Colby was on the village board, was the village's Fire Commissioner, and researched the Historical Society's 1974 history.[2][26][131] Anna Roosevelt Halsted lived with Curtis Bean Dall on Sleepy Hollow Road.[26] John Cheever lived in Scarborough, and spent most of his writing career in Westchester towns such as Briarcliff Manor and Ossining.[132] He served in the Briarcliff Manor Fire Department.[26] Coby Whitmore, a painter and magazine illustrator, lived in the village from 1945 to 1965. Pulitzer Prize-winning writer and journalist John Hersey attended public school and lived in Briarcliff Manor; he was the village's first Eagle Scout and a lifeguard at the village pool, and his mother was a village librarian.[2][133][134] Folk singer and songwriter Tom Glazer lived in Scarborough for nearly 30 years.[2] Mathematician Bryant Tuckerman, who helped develop the Data Encryption Standard, was a long-time village resident.[135] Ely Jacques Kahn, Jr., a writer for The New Yorker, lived in Scarborough for more than 20 years, and was a member of the village fire department.[26] His father (Ely Jacques Kahn, a New York skyscraper architect) designed two houses in Briarcliff Manor, including one for sports commentator Red Barber.[2] Burton Benjamin, former vice president and director of CBS News, lived in the village for about 30 years. Harcourt president William Jovanovich lived in Briarcliff Manor for 27 years.[2] Leonard Jacobson, a museum architect and colleague of I. M. Pei, lived in the village.[136] John Kelvin Koelsch, a U.S. Navy officer during the Korean War and the first helicopter pilot to receive the Medal of Honor, lived in Scarborough and attended the Scarborough School.[137] Novelist and short-story writer Richard Yates lived at the corner of Revolutionary Road and Route 9 in Scarborough as a boy, and named his novel Revolutionary Road; it was made into a 2008 film.[138] Rolf Landauer, a German-American physicist and a refugee from Nazi Germany, lived in the village.[139] Author Sol Stein, founder and former president of the Briarcliff Manor-based Stein and Day, was a village resident.[2][140] Physicist Praveen Chaudhari, an innovator in thin films and high-temperature superconductors, lived in Briarcliff Manor.[141] Cardiac surgeon Peter Praeger, a founder, president and chief executive of Dr. Praeger’s Sensible Foods, was a village resident.[142]

The Webb family lived on the Beechwood Estate. Notable family members who lived at the estate include Henry Walter Webb, a New York Central Railroad executive who bought the property during the 1890s; Webb's cousin George Webb Morell, a Union Army brigadier general during the American Civil War, and Webb's half-brother Alexander S. Webb, a Union major general during the Civil War and a Medal of Honor recipient. Other family members were James Watson Webb (father of Henry Walter Webb), a diplomat, newspaper publisher and New York politician; General Samuel Blatchley Webb (father of James Watson Webb), an aide to George Washington; and businessman William Seward Webb (brother of Henry Walter Webb), founder and president of the Sons of the American Revolution. Colonel Elliot Fitch Shepard, brother-in-law of William Seward Webb and aide-de-camp to New York governor Edwin D. Morgan, lived in Scarborough.[2]

Present-day[edit]

Alice Low, who with her family has lived in Briarcliff Manor since the 1950s, is an author of children's books, poems and screenplays.[2] Composer, pianist and local historian Carmino Ravosa is a trustee of the Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough Historical Society.[137][143] Minimalist painter Brice Marden grew up in the village, and is a 1965 graduate of Briarcliff High School.[144][145] Roz Abrams is a national-news anchor known for her work with WABC and WCBS.[146] Director, writer and producer Joseph Ruben lives in Briarcliff Manor,[147] and musician Clifford Carter is graduate of Briarcliff High School.[148] Thomas Fitzgerald is a senior creative executive at Walt Disney Imagineering.[149] Tom Ortenberg, CEO of Open Road Films and former president of Lionsgate Films, was born and raised in Briarcliff Manor.[150] Doris Downes, a botanical artist and widow of art critic Robert Hughes, owns a farmhouse in the village (where they lived for many years).[151][152] Curler Bill Stopera has lived in the village for over a decade,[153][154] and Olympic swimmer Paola Duguet grew up in Briarcliff Manor.[155]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Brier" is a variant spelling of "briar", a word used for a number of unrelated thicket-forming thorny plants.

- ^ Sing Sing was the name of the neighboring village Ossining, New York until 1901.[2]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Weinstock, Cheryl (April 2, 2000). "If You're Thinking of Living In/Briarcliff Manor; Small-Town Quality But Near Manhattan". The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Cheever, Mary (1990). The Changing Landscape: A History of Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough. West Kennebunk, Maine: Phoenix Publishing. ISBN 0-914659-49-9. OCLC 22274920.

- ^ a b c d e f Briarcliff Manor Centennial Committee (2002). The Briarcliff Manor Family Album: Celebrating a Century. Cornwall N.Y: Village of Briarcliff Manor.

- ^ "$12,000,000 Realty Transfer; W.W. Law Makes Record Deed of Land to His Own Company for $5". The New York Times. February 2, 1908. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "New Agricultural School.; Briar Cliff Farm Selected by Abram S. Hewitt and His Associates". The New York Times. May 1, 1900. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "J.D. Rockefeller, Jr. Real Fire Fighter; Takes Command When Stable on Father's Pocantico Estate Burns". The New York Times. July 1, 1913. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Midge Bosak, ed. (1977). A Village Between Two Rivers: Briarcliff Manor. Monarch Publishing, Inc.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Gelard, Donna (2002). Explore Briarcliff Manor: A driving tour. Contributing Editor Elsie Smith; layout and typography by Lorraine Gelard; map, illustrations, and calligraphy by Allison Krasner. Briarcliff Manor Centennial Committee.

- ^ What the Name Ossining Means. March 2, 1901.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Ruttenber, Edward (1872). History of the Indian tribes of Hudson's River; their origin, manners and customs; tribal and sub-tribal organizations; wars, treaties, etc., etc. Albany: J. Munsell. p. 372. ISBN 9781279172216. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Our Village: Briarcliff Manor, N.Y. 1902 to 1952. Historical Committee of the Semi–Centennial. 1952.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Pattison, Robert (1939). A History of Briarcliff Manor. William Rayburn. OCLC 39333547.

- ^ Pelletreau, William (1886). History of Putnam County, New York: with biographical sketches of its prominent men.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Boesch, Eugene. "Native Americans of Putnam County". Mahopac Public Library. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b Oechsner, Carl (1975). Ossining, New York: An Informal Bicentennial History. Croton-on-Hudson: North River Press. ISBN 0-88427-016-5.

- ^ a b c d e Yasinsac, Robert (2004). Images of America: Briarcliff Lodge. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-3620-0. OCLC 57480785.

- ^ a b c d e f Sharman, Karen (1996). Glory in Glass: A Celebration of The Briarcliff Congregational Church. ISBN 0-912882-96-4. OCLC 429606439.

- ^ a b c d "Our Village: a family place for more than a century". Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough Historical Society. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Blossom, Mary C. (1901). Page, Walter Hines (ed.). "The New Farming and a New Life". The World's Work. 3. Doubleday, Page & Company: 1625–1637.

- ^ Briarcliff Outlook: For Promotion of Country Life, Volume III. Briarcliff Manor, New York. 1904. pp. 56 and 67. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Briarcliff Lodge - Names of Many New Yorkers on the Hotel Registers". The New York Times. June 16, 1912. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Briarcliff Manor - Fall Programme of Outdoor Sports and Pastimes". The New York Times. September 5, 1909. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b Leahy, Michael (1999). If You're Thinking of Living In...: All About 115 Great Neighborhoods In & Around New York. New York: Random House LLC. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-307-42107-4.

- ^ Catalog of Copyright Entries. New Series: 1926, Part 1. Library of Congress Copyright Office. 1927. p. 1386. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Segal, David (February 20, 2008). "God and The City". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g A Century of Volunteer Service: Briarcliff Manor Fire Department 1901–2001. Briarcliff Manor Fire Department. 2001. LCCN 00-093475.

- ^ a b c Briarcliff Manor: The First 100 Years – The Centennial Variety Show. Village of Briarcliff Manor. 2002.

- ^ Folsom, Merrill (May 30, 1958). "The Wheels of 'Old Put' Click Out a Sad Accompaniment to Riders' 'Auld Lang Syne'". The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Photograph by Michael Raphael taken on 09/19/1999 in New York". FEMA. Michael Raphael/FEMA News Photo. September 16, 1999. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b Garofalo, Michael (December 13, 2013). "Ossining Moves Forward With Annexation Process". Hudson Valley Reporter. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Zegarelli, Philip E. "Village Manager's Report – October 18". Village of Briarcliff Manor. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Shillinglaw, Greg (March 12, 2014). "1 Briarcliff Manor could take annexation to court". The Journal News. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Combined Statistical Areas, and Guidance on Uses of the Delineations of These Areas" (PDF). Whitehouse.gov. Washington, D.C.: Executive Office of the President: Office of Management and Budget. February 28, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Emergency Response Planning Areas (ERPAs) and General Population Reception Centers" (Map). Emergency Planning Map for Westchester County (PDF). Oak Ridge Associated Universities for U.S. Department of Energy. 2004. p. 2. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Briarcliff Manor Village Court". Law Office of Jared Altman. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Stefko, Joseph (April 2012). "Municipal Services & Financial Overview: Town and Village of Ossining, NY" (PDF). Town and Village of Ossining, NY. Center for Governmental Research. p. 87. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. "World Map of Köppen-Geiger climate classification". The University of Melbourne. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ United States Department of Agriculture. "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". United States National Arboretum. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Monthly Weather for Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510". The Weather Channel, LLC. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b "Average Weather for Briarcliff Manor, NY (10510)". The Weather Channel, LLC. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b "Scarborough Historic District". Living Places. The Gombach Group. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Village of Ossining, New York - Significant Sites and Structures Guide" (PDF). Village of Ossining. April 2010. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Reed, M. H. (June 4, 2006). "Tasty Multitasking on Main Street". The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Zetkov-Lubin, Susan (August 26, 2012). "A Tribute to the United States Armed Forces, a Blue Star By-Way Marker Dedication". Pleasantville-Briarcliff Manor Patch. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b Moorhead-Lins, Parry (May 24, 2013). "Briarcliff Traditions: Memorial Day". River Journal. River Journal Inc. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Comprehensive Plan - Village of Briarcliff Manor" (PDF). Village of Briarcliff Manor. November 2007. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b "State & County QuickFacts: Briarcliff Manor (village), New York". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010". United States Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics: Briarcliff Manor village, New York". American FactFinder. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Philips Research North America - Briarcliff". Philips. Koninklijke Philips N.V. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Cox, Jeff. "25 top-earning towns – 19. Briarcliff Manor, N.Y." CNN. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "America's Richest School Districts". Fox Business. 24/7 Wall St. June 8, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Marchant, Robert (June 29, 2006). "Historic Briarcliff rose adorns new street signs". The Journal News.

- ^ Nackman, Barbara (November 11, 2010). "Briarcliff Cub Scouts begin holiday cheer". The Journal News. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "5 Briarcliff Manor Scouts earn Eagle honors". The Journal News. June 2, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Annual Briarcliff Bonfire And Holiday Sing-a-Long Starts Dec. 8". Briarcliff Daily Voice. November 30, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Brown, Stacy (May 9, 2001). "Memorial Day march to return to park". The Journal News.

- ^ "Our History: a look back through four decades". Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough Historical Society. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Salerno, Heather (June 24, 2004). "Mystery writer Patterson savors killer view". USA Today. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Salvto, Sharon (1974). Briarcliff Manor. Briarcliff Manor, New York: Stein and Day. ISBN 0812816617. OCLC 865174.

- ^ "George Carlin / Billy Preston, Janis Ian: Show Us Your Guns". Saturday Night Live. Season 1. Episode 1. The GE Building, New York City. October 11, 1975. Occurs at time 45′ 27″. ASIN B000XJUBLQ. NBC. Saturday Night Live Transcripts.

{{cite episode}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Studley, Sarah (October 31, 2011). "Hollywood Comes to Briarcliff Manor". Pleasantville-Briarcliff Manor Patch. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Studley, Sarah (August 18, 2011). "New TV Show 'Pan Am' Shoots at SH Country Club". Tarrytown-Sleepy Hollow Patch. Archived from the original on January 5, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Film Made at Briarcliff". June 7, 1915. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Ivory, James (1973). Savages, Shakespeare Wallah: Two Films by James Ivory (1st ed.). New York: Plexus Publishing Ltd. pp. 7–9. ISBN 0-394-17799-1.

- ^ Stafford, Jeff. "House of Dark Shadows". Turner Classic Movies. Turner Entertainment Networks, Inc. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Dawson, Nick (August 24, 2009). "Hudson Valley Movies". NBC Universal. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "American Gangster Full Production Notes". Universal Pictures. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Carrie Chapman Catt House". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. October 2003. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b "Catt, Carrie Chapman, House - Westchester County, New York". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b c "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009. Cite error: The named reference "nris" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Historic Properties Listing". Westchester County Historical Society. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Old Croton Aqueduct State Historic Park". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Croton Aqueduct (Old)". National Park Service. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "A Passion for History Leads a Hartt Alumnus down the Path to Historic Preservation" (PDF). University of Hartford Observer. University of Hartford: 25. 2005. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Ganga, Elizabeth. "Landmark Status for Catt Home". The Northern Westchester Examiner.

- ^ "Your Rivertown Houses of Worship". River Journal. Vol. 16, no. Year Ahead 2014. January 25, 2014. p. 6. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b "National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination form - Scarborough Historic District". National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "The History of Scarborough Presbyterian Church". Scarborough Presbyterian Church. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b "National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination form - All Saints' Episcopal Church". National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ The Golden Anniversary of St. Theresa's Parish. White Plains: Monarch Publishing, Inc. 1976.

- ^ "Welcome! This is who we are..." Congregation Sons of Israel. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Student Affairs and Campus Life". Pace University. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b "April / May 1999 Feature - 1908 Briarcliff-to-Yorktown Stock Car Race". The Yorktown Historical Society. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Merrihew, S. Wallis, ed. (January 11, 1908). "Extend the Date for the Closing of Entries". Automobile Topics. 15 (14). New York: Automobile Topics Inc.: 1106. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Thousands to See Briarcliff Race". The New York Times. April 24, 1908. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ a b Schweber, Nate (October 24, 2008). "Autos and Heirs Mark the Centennial of a Road Race". The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Recreation Facilities & Parks". Village of Briarcliff Manor. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Briarcliff-Peekskill Trailway" (PDF). Westchester County Department of Parks, Recreation & Conservation. 2005. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Town of Mount Pleasant Recreation and Parks Department Park Facilities" (PDF). Town of Mount Pleasant. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Briarcliff Manor Recreation Department". Village of Briarcliff Manor. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Youth Center General Information" (PDF). Village of Briarcliff Manor. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Bruttell, Nathan (December 12, 2012). "Briarcliff Moves Ice Rink From Pond To Tennis Courts". Briarcliff Daily Voice. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "About the Library - Library History". Briarcliff Manor Public Library. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "North Country Trailway" (PDF). Westchester County Department of Parks, Recreation & Conservation. 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Leonard, Devin (April 5, 1999). "Trump's Garish Golf Course Plan Disrupts Quiet Westchester Town". The New York Observer. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Williams, Gray (2003). Picturing Our Past: National Register Sites in Westchester County. Westchester County Historical Society. ISBN 0-915585-14-6.

- ^ Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough Historical Society 2012 Harvest Wine Dinner. Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough Historical Society. 2012.

- ^ Bonvento, Robert (July 28, 2011). "Let the Water Flow… Briarcliff's New Pump Station". River Journal. River Journal Inc. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "About Briarcliff Manor". Village of Briarcliff Manor. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Village Manager". Village of Briarcliff Manor. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Mayor & Board of Trustees". Village of Briarcliff Manor. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Justice Court". Village of Briarcliff Manor. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Egan, Bobbi (February 21, 2014). "Briarcliff Manor Village Election to Take Place on Tuesday, March 18th". River Journal. Vol. 16, no. Winter 2014. pp. 1, 19. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "District Map for Sandy Galef". New York State Assembly. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Biography of Thomas J. Abinanti". New York State Assembly. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "District Map for David Carlucci". New York State Senate. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "District Map for Greg Ball". New York State Senate. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Senators and representatives for New York". Govtrack.us. Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ The Daily Voice (January 10, 2014). "Briarcliff Named One Of New York's Safest Communities". Briarcliff Daily Voice. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Cross, David. "The 10 Safest Places In New York". Movoto.com. Movoto LLC. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Gross, Jane (May 4, 2003). "In High School, Putting on a Show Means Broadway Dazzle". The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "List of Blue Ribbon Schools" (PDF). Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Cortissoz, Marie (February 28, 2013). "Walkabout Program Helped Budding 'Cupcake Queen'". Pleasantville-Briarcliff Manor Patch. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "WXPK Facility Record". CDBS Public Access Database. Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Fischer, Jack (February 20, 2013). "Hyperlocal Overload?". The Briarcliff Bulletin. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Police Department". Briarcliff Manor. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Emergency Medical Services". Village of Briarcliff Manor. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Bruttell, Nathan (October 17, 2013). "Catskill Aqueduct Work Affecting Briarcliff Water Supply". Briarcliff Daily Voice. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Public Works Department". Village of Briarcliff Manor. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "County Recycling Rate Continues to Exceed National Average". Westchestergov.com. Westchester County. June 13, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Department of Public Works Staff". Village of Briarcliff Manor. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "The National Bridge Inventory Database". Nationalbridges. National Bridge Inventory. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Auchterlonie, Tom (May 10, 2012). "Old Millwood Train Station Demolished". Pleasantville-Briarcliff Manor Patch. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Foderaro, Lisa (February 23, 2007). "Spending a Day at the Rockefellers'". The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2014.