User:سائغ/page4

[1] Although this statistical method was modern and innovative, the actual decipherment of the script would have to wait until after the discovery of bilingual inscriptions, a few years later.[2]

The same year, in 1834, some attempts by Rev. J. Stevenson were made to identify intermediate early Brahmi characters from the Karla Caves (circa 1st century CE) based on their similarities with the Gupta script of the Samudragupta inscription of the Allahabad pillar (4th century CE) which had just been published, but this led to a mix of good (about 1/3) and bad guesses, which did not permit proper decipherment of the Brahmi.[3][1]

The next major step towards deciphering the ancient Brahmi script of the 3rd-2nd centuries BCE was made in 1836 by Norwegian scholar Christian Lassen, who used a bilingual Greek-Brahmi coin of Indo-Greek king Agathocles and similarities with the Pali script to correctly and securely identify several Brahmi letters.[4][1][5] The matching legends on the bilingual coins of Agathocles were:

Greek legend: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ / ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ (Basileōs Agathokleous, "of King Agathocles")

Brahmi legend:𑀭𑀚𑀦𑁂 / 𑀅𑀕𑀣𑀼𑀼𑀓𑁆𑀮𑁂𑀬𑁂𑀲 (Rajane Agathukleyesa, "King Agathocles").[6]

James Prinsep was then able to complete the decipherment of the Brahmi script.[1][7][4][8] After acknowledging Lassen's first decipherment,[9] Prinsep used a bilingual coin of Indo-Greek king Pantaleon to decipher a few more letters.[5] James Prinsep then analysed a large number of donatory inscriptions on the reliefs in Sanchi, and noted that most of them ended with the same two Brahmi characters: "𑀤𑀦𑀁". Prinsep guessed correctly that they stood for "danam", the Sanskrit word for "gift" or "donation", which permitted to further increase the number of known letters.[1][10] With the help of Ratna Pâla, a Singhalese Pali scholar and linguist, Prinsep then completed the full decipherment of the Brahmi script.[11][12][13][14] In a series of results that he published in March 1838 Prinsep was able to translate the inscriptions on a large number of rock edicts found around India, and provide, according to Richard Salomon, a "virtually perfect" rendering of the full Brahmi alphabet.[15][16]

Southern Brahmi[edit]

Ashokan inscriptions are found all over India and a few regional variants have been observed. The Bhattiprolu alphabet, with earliest inscriptions dating from a few decades of Ashoka's reign, is believed to have evolved from a southern variant of the Brahmi alphabet. The language used in these inscriptions, nearly all of which have been found upon Buddhist relics, is exclusively Prakrit, though Kannada and Telugu proper names have been identified in some inscriptions. Twenty-three letters have been identified. The letters ga and sa are similar to Mauryan Brahmi, while bha and da resemble those of modern Kannada and Telugu script.

Tamil-Brahmi is a variant of the Brahmi alphabet that was in use in South India by about 3rd century BCE, particularly in Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Inscriptions attest their use in parts of Sri Lanka in the same period. The language used in around 70 Southern Brahmi inscriptions discovered in the 20th century have been identified as a Prakrit language.[17][18]

In English, the most widely available set of reproductions of Brahmi texts found in Sri Lanka is Epigraphia Zeylanica; in volume 1 (1976), many of the inscriptions are dated from the 3rd to 2nd century BCE.[19]

Unlike the edicts of Ashoka, however, the majority of the inscriptions from this early period in Sri Lanka are found above caves. The language of Sri Lanka Brahmi inscriptions has been mostly been Prakrit though some Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions have also been found, such as the Annaicoddai seal.[20] The earliest widely accepted examples of writing in Brahmi are found in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka.[21]

Red Sea and Southeast Asia[edit]

The Khuan Luk Pat inscription discovered in Thailand is in Tamil Brahmi script. Its date is uncertain and has been proposed to be from the early centuries of the common era.[22][23] According to Frederick Asher, Tamil Brahmi inscriptions on potsherds have been found in Quseir al-Qadim and in Berenike, Egypt which suggest that merchant and trade activity was flourishing in ancient times between India and the Red Sea region.[23] Additional Tamil Brahmi inscription has been found in Khor Rori region of Oman on an archaeological site storage jar.[23]

Characteristics[edit]

Brahmi is usually written from left to right, as in the case of its descendants. However, an early coin found in Eran is inscribed with Brahmi running from right to left, as in Aramaic. Several other instances of variation in the writing direction are known, though directional instability is fairly common in ancient writing systems.[24]

Consonants[edit]

Brahmi is an abugida, meaning that each letter represents a consonant, while vowels are written with obligatory diacritics called mātrās in Sanskrit, except when the vowels commence a word. When no vowel is written, the vowel /a/ is understood. This "default short a" is a characteristic shared with Kharosthī, though the treatment of vowels differs in other respects.

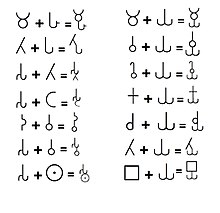

Conjunct consonants[edit]

Special conjunct consonants are used to write consonant clusters such as /pr/ or /rv/. In modern Devanagari the components of a conjunct are written left to right when possible (when the first consonant has a vertical stem that can be removed at the right), whereas in Brahmi characters are joined vertically downwards.

-

Sva (Sa+Va)

-

Sya (Sa+Ya)

-

Hmī (Ha+Ma+i+i), as in the word "Brāhmī" (𑀩𑁆𑀭𑀸𑀳𑁆𑀫𑀻).

Vowels[edit]

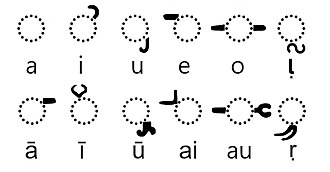

Vowels following a consonant are inherent or written by diacritics, but initial vowels have dedicated letters. There are three "primary" vowels in Ashokan Brahmi, which each occur in length-contrasted forms: /a/, /i/, /u/; long vowels are derived from the letters for short vowels. There are also four "secondary" vowels that do not have the long-short contrast, /e/, /ai/, /o/, /au/.[25] Note though that the grapheme for /ai/ is derivative from /e/ in a way which parallels the short-long contrast of the primary vowels. However, there are only nine distinct vowel diacritics, as short /a/ is understood if no vowel is written. The initial vowel symbol for /au/ is also apparently lacking in the earliest attested phases, even though it has a diacritic. Ancient sources suggest that there were either 11 or 12 vowels enumerated at the beginning of the character list around the Ashokan era, probably adding either aṃ or aḥ.[26] Later versions of Brahmi add vowels for four syllabic liquids, short and long /ṛ/ and /ḷ/. Chinese sources indicate that these were later inventions by either Nagarjuna or Śarvavarman, a minister of King Hāla.[27]

It has been noted that the basic system of vowel marking common to Brahmi and Kharosthī, in which every consonant is understood to be followed by a vowel, was well suited to Prakrit,[28] but as Brahmi was adapted to other languages, a special notation called the virāma was introduced to indicate the omission of the final vowel. Kharoṣṭhī also differs in that the initial vowel representation has a single generic vowel symbol that is differentiated by diacritics, and long vowels are not distinguished.

The collation order of Brahmi is believed to have been the same as most of its descendant scripts, one based on Shiksha, the traditional Vedic theory of Sanskrit phonology. This begins the list of characters with the initial vowels (starting with a), then lists a subset of the consonants in five phonetically-related groups of five called vargas, and ends with four liquids, three sibilants, and a spirant. Thomas Trautmann attributes much of the popularity of the Brahmic script family to this "splendidly reasoned" system of arrangement.[29]

| k- | kh- | g- | gh- | ṅ- | c- | ch- | j- | jh- | ñ- | ṭ- | ṭh- | ḍ- | ḍh- | ṇ- | t- | th- | d- | dh- | n- | p- | ph- | b- | bh- | m- | y- | r- | l- | v- | ś- | ṣ- | s- | h- | ḷ- | |

| -a | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀯 | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 | 𑀴 |

| -ā | 𑀓𑀸 | 𑀔𑀸 | 𑀕𑀸 | 𑀖𑀸 | 𑀗𑀸 | 𑀘𑀸 | 𑀙𑀸 | 𑀚𑀸 | 𑀛𑀸 | 𑀜𑀸 | 𑀝𑀸 | 𑀞𑀸 | 𑀟𑀸 | 𑀠𑀸 | 𑀡𑀸 | 𑀢𑀸 | 𑀣𑀸 | 𑀤𑀸 | 𑀥𑀸 | 𑀦𑀸 | 𑀧𑀸 | 𑀨𑀸 | 𑀩𑀸 | 𑀪𑀸 | 𑀫𑀸 | 𑀬𑀸 | 𑀭𑀸 | 𑀮𑀸 | 𑀯𑀸 | 𑀰𑀸 | 𑀱𑀸 | 𑀲𑀸 | 𑀳𑀸 | 𑀴𑀸 |

| -i | 𑀓𑀺 | 𑀔𑀺 | 𑀕𑀺 | 𑀖𑀺 | 𑀗𑀺 | 𑀘𑀺 | 𑀙𑀺 | 𑀚𑀺 | 𑀛𑀺 | 𑀜𑀺 | 𑀝𑀺 | 𑀞𑀺 | 𑀟𑀺 | 𑀠𑀺 | 𑀡𑀺 | 𑀢𑀺 | 𑀣𑀺 | 𑀤𑀺 | 𑀥𑀺 | 𑀦𑀺 | 𑀧𑀺 | 𑀨𑀺 | 𑀩𑀺 | 𑀪𑀺 | 𑀫𑀺 | 𑀬𑀺 | 𑀭𑀺 | 𑀮𑀺 | 𑀯𑀺 | 𑀰𑀺 | 𑀱𑀺 | 𑀲𑀺 | 𑀳𑀺 | 𑀴𑀺 |

| -ī | 𑀓𑀻 | 𑀔𑀻 | 𑀕𑀻 | 𑀖𑀻 | 𑀗𑀻 | 𑀘𑀻 | 𑀙𑀻 | 𑀚𑀻 | 𑀛𑀻 | 𑀜𑀻 | 𑀝𑀻 | 𑀞𑀻 | 𑀟𑀻 | 𑀠𑀻 | 𑀡𑀻 | 𑀢𑀻 | 𑀣𑀻 | 𑀤𑀻 | 𑀥𑀻 | 𑀦𑀻 | 𑀧𑀻 | 𑀨𑀻 | 𑀩𑀻 | 𑀪𑀻 | 𑀫𑀻 | 𑀬𑀻 | 𑀭𑀻 | 𑀮𑀻 | 𑀯𑀻 | 𑀰𑀻 | 𑀱𑀻 | 𑀲𑀻 | 𑀳𑀻 | 𑀴𑀻 |

| -u | 𑀓𑀼 | 𑀔𑀼 | 𑀕𑀼 | 𑀖𑀼 | 𑀗𑀼 | 𑀘𑀼 | 𑀙𑀼 | 𑀚𑀼 | 𑀛𑀼 | 𑀜𑀼 | 𑀝𑀼 | 𑀞𑀼 | 𑀟𑀼 | 𑀠𑀼 | 𑀡𑀼 | 𑀢𑀼 | 𑀣𑀼 | 𑀤𑀼 | 𑀥𑀼 | 𑀦𑀼 | 𑀧𑀼 | 𑀨𑀼 | 𑀩𑀼 | 𑀪𑀼 | 𑀫𑀼 | 𑀬𑀼 | 𑀭𑀼 | 𑀮𑀼 | 𑀯𑀼 | 𑀰𑀼 | 𑀱𑀼 | 𑀲𑀼 | 𑀳𑀼 | 𑀴𑀼 |

| -ū | 𑀓𑀽 | 𑀔𑀽 | 𑀕𑀽 | 𑀖𑀽 | 𑀗𑀽 | 𑀘𑀽 | 𑀙𑀽 | 𑀚𑀽 | 𑀛𑀽 | 𑀜𑀽 | 𑀝𑀽 | 𑀞𑀽 | 𑀟𑀽 | 𑀠𑀽 | 𑀡 | 𑀢𑀽 | 𑀣𑀽 | 𑀤𑀽 | 𑀥𑀽 | 𑀦𑀽 | 𑀧𑀽 | 𑀨𑀽 | 𑀩𑀽 | 𑀪𑀽 | 𑀫𑀽 | 𑀬𑀽 | 𑀭𑀽 | 𑀮𑀽 | 𑀯𑀽 | 𑀰𑀽 | 𑀱𑀽 | 𑀲𑀽 | 𑀳𑀽 | 𑀴𑀽 |

| -e | 𑀓𑁂 | 𑀔𑁂 | 𑀕𑁂 | 𑀖𑁂 | 𑀗𑁂 | 𑀘𑁂 | 𑀙𑁂 | 𑀚𑁂 | 𑀛𑁂 | 𑀜𑁂 | 𑀝𑁂 | 𑀞𑁂 | 𑀟𑁂 | 𑀠𑁂 | 𑀡 | 𑀢𑁂 | 𑀣𑁂 | 𑀤𑁂 | 𑀥𑁂 | 𑀦𑁂 | 𑀧𑁂 | 𑀨𑁂 | 𑀩𑁂 | 𑀪𑁂 | 𑀫𑁂 | 𑀬𑁂 | 𑀭𑁂 | 𑀮𑁂 | 𑀯𑁂 | 𑀰𑁂 | 𑀱𑁂 | 𑀲𑁂 | 𑀳𑁂 | 𑀴𑁂 |

| -o | 𑀓𑁄 | 𑀔𑁄 | 𑀕𑁄 | 𑀖𑁄 | 𑀗𑁄 | 𑀘𑁄 | 𑀙𑁄 | 𑀚𑁄 | 𑀛𑁄 | 𑀜𑁄 | 𑀝𑁄 | 𑀞𑁄 | 𑀟𑁄 | 𑀠𑁄 | 𑀡 | 𑀢𑁄 | 𑀣𑁄 | 𑀤𑁄 | 𑀥𑁄 | 𑀦𑁄 | 𑀧𑁄 | 𑀨𑁄 | 𑀩𑁄 | 𑀪𑁄 | 𑀫𑁄 | 𑀬𑁄 | 𑀭𑁄 | 𑀮𑁄 | 𑀯𑁄 | 𑀰𑁄 | 𑀱𑁄 | 𑀲𑁄 | 𑀳𑁄 | 𑀴𑁄 |

| -Ø | 𑀓𑁆 | 𑀔𑁆 | 𑀕𑁆 | 𑀖𑁆 | 𑀗𑁆 | 𑀘𑁆 | 𑀙𑁆 | 𑀚𑁆 | 𑀛𑁆 | 𑀜𑁆 | 𑀝𑁆 | 𑀞𑁆 | 𑀟𑁆 | 𑀠𑁆 | 𑀡𑁆 | 𑀢𑁆 | 𑀣𑁆 | 𑀤𑁆 | 𑀥𑁆 | 𑀦𑁆 | 𑀧𑁆 | 𑀨𑁆 | 𑀩𑁆 | 𑀪𑁆 | 𑀫𑁆 | 𑀬𑁆 | 𑀭𑁆 | 𑀮𑁆 | 𑀯𑁆 | 𑀰𑁆 | 𑀱𑁆 | 𑀲𑁆 | 𑀳𑁆 | 𑀴𑁆 |

Punctuation[edit]

Punctuation[31] can be perceived as more of an exception than as a general rule in Asokan Brahmi. For instance, distinct spaces in between the words appear frequently in the pillar edicts but not so much in others. ("Pillar edicts" refers to the texts that are inscribed on the stone pillars oftentimes with the intention of making them public.) The idea of writing each word separately was not consistently used.

In the early Brahmi period, the existence of punctuation marks is not very well shown. Each letter has been written independently with some occasional space between words and longer sections.

In the middle period, the system seems to be developing. The use of a dash and a curved horizontal line is found. A lotus (flower) mark seems to mark the end, and a circular mark appears to indicate the full stop. There seem to be varieties of full stop.

In the late period, the system of interpunctuation marks gets more complicated. For instance, there are four different forms of vertically slanted double dashes that resemble "//" to mark the completion of the composition. Despite all the decorative signs that were available during the late period, the signs remained fairly simple in the inscriptions. One of the possible reasons may be that engraving is restricted while writing is not.

Baums identifies seven different punctuation marks needed for computer representation of Brahmi:[32]

- single (𑁇) and double (𑁈) vertical bar (danda) – delimiting clauses and verses

- dot (𑁉), double dot (𑁊), and horizontal line (𑁋) – delimiting shorter textual units

- crescent (𑁌) and lotus (𑁍) – delimiting larger textual units

Evolution of the Brahmi script[edit]

Brahmi is generally classified in three main types, which represent three main historical stages of its evolution over nearly a millennium:[33]

- Early Brahmi or "Ashokan Brahmi" (3rd-1st century BCE)

- Middle Brahmi or "Kushana Brahmi" (1st-3rd centuries CE)

- Late Brahmi or "Gupta Brahmi", also called Gupta script (4th-6th centuries CE)

| Evolution of the Brahmi script[34] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k- | kh- | g- | gh- | ṅ- | c- | ch- | j- | jh- | ñ- | ṭ- | ṭh- | ḍ- | ḍh- | ṇ- | t- | th- | d- | dh- | n- | p- | ph- | b- | bh- | m- | y- | r- | l- | v- | ś- | ṣ- | s- | h- | |

| Ashoka[35] | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀯 | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 |

| Girnar[36] | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kushan[37] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gujarat | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gupta[38] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Early Brahmi or "Ashokan Brahmi" (3rd–1st century BCE)[edit]

Early "Ashokan" Brahmi (3rd–1st century BCE) is regular and geometric, and organized in a very rational fashion:

Independent vowels[edit]

| Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Mātrā | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Mātrā | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𑀅 | a /ə/ | 𑀓 | ka /kə/ | 𑀆 | ā /aː/ | 𑀓𑀸 | kā /kaː/ |

| 𑀇 | i /i/ | 𑀓𑀺 | ki /ki/ | 𑀈 | ī /iː/ | 𑀓𑀻 | kī /kiː/ |

| 𑀉 | u /u/ | 𑀓𑀼 | ku /ku/ | 𑀊 | ū /uː/ | 𑀓𑀽 | kū /kuː/ |

| 𑀏 | e /eː/ | 𑀓𑁂 | ke /keː/ | 𑀑 | o /oː/ | 𑀓𑁄 | ko /koː/ |

| 𑀐 | ai /əi/ | 𑀓𑁃 | kai /kəi/ | 𑀒 | au /əu/ | 𑀓𑁅 | kau /kəu/ |

Consonants[edit]

| Stop | Nasal | Approximant | Fricative | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||||

| Velar | 𑀓 | ka /k/ | 𑀔 | kha /kʰ/ | 𑀕 | ga /ɡ/ | 𑀖 | gha /ɡʱ/ | 𑀗 | ṅa /ŋ/ | 𑀳 | ha /ɦ/ | ||||

| Palatal | 𑀘 | ca /c/ | 𑀙 | cha /cʰ/ | 𑀚 | ja /ɟ/ | 𑀛 | jha /ɟʱ/ | 𑀜 | ña /ɲ/ | 𑀬 | ya /j/ | 𑀰 | śa /ɕ/ | ||

| Retroflex | 𑀝 | ṭa /ʈ/ | 𑀞 | ṭha /ʈʰ/ | 𑀟 | ḍa /ɖ/ | 𑀠 | ḍha /ɖʱ/ | 𑀡 | ṇa /ɳ/ | 𑀭 | ra /r/ | 𑀱 | ṣa /ʂ/ | ||

| Dental | 𑀢 | ta /t̪/ | 𑀣 | tha /t̪ʰ/ | 𑀤 | da /d̪/ | 𑀥 | dha /d̪ʱ/ | 𑀦 | na /n/ | 𑀮 | la /l/ | 𑀲 | sa /s/ | ||

| Labial | 𑀧 | pa /p/ | 𑀨 | pha /pʰ/ | 𑀩 | ba /b/ | 𑀪 | bha /bʱ/ | 𑀫 | ma /m/ | 𑀯 | va /w, ʋ/ | ||||

The final letter does not fit into the table above; it is 𑀴 ḷa.

Unicode and digitization[edit]

Early Ashokan Brahmi was added to the Unicode Standard in October, 2010 with the release of version 6.0.

The Unicode block for Brahmi is U+11000–U+1107F. It lies within Supplementary Multilingual Plane. As of August 2014 there are two non-commercially available fonts that support Brahmi, namely Noto Sans Brahmi commissioned by Google which covers all the characters,[39] and Adinatha which only covers Tamil Brahmi.[40] Segoe UI Historic, tied in with Windows 10, also features Brahmi glyphs.[41]

The Sanskrit word for Brahmi, ब्राह्मी (IAST Brāhmī) in the Brahmi script should be rendered as follows: 𑀩𑁆𑀭𑀸𑀳𑁆𑀫𑀻.

| Brahmi[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1100x | 𑀀 | 𑀁 | 𑀂 | 𑀃 | 𑀄 | 𑀅 | 𑀆 | 𑀇 | 𑀈 | 𑀉 | 𑀊 | 𑀋 | 𑀌 | 𑀍 | 𑀎 | 𑀏 |

| U+1101x | 𑀐 | 𑀑 | 𑀒 | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 |

| U+1102x | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀯 |

| U+1103x | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 | 𑀴 | 𑀵 | 𑀶 | 𑀷 | 𑀸 | 𑀹 | 𑀺 | 𑀻 | 𑀼 | 𑀽 | 𑀾 | 𑀿 |

| U+1104x | 𑁀 | 𑁁 | 𑁂 | 𑁃 | 𑁄 | 𑁅 | 𑁆 | 𑁇 | 𑁈 | 𑁉 | 𑁊 | 𑁋 | 𑁌 | 𑁍 | ||

| U+1105x | 𑁒 | 𑁓 | 𑁔 | 𑁕 | 𑁖 | 𑁗 | 𑁘 | 𑁙 | 𑁚 | 𑁛 | 𑁜 | 𑁝 | 𑁞 | 𑁟 | ||

| U+1106x | 𑁠 | 𑁡 | 𑁢 | 𑁣 | 𑁤 | 𑁥 | 𑁦 | 𑁧 | 𑁨 | 𑁩 | 𑁪 | 𑁫 | 𑁬 | 𑁭 | 𑁮 | 𑁯 |

| U+1107x | 𑁰 | 𑁱 | 𑁲 | 𑁳 | 𑁴 | 𑁵 | BNJ | |||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Some famous inscriptions in the Early Brahmi script[edit]

The Brahmi script was the medium for some of the most famous inscriptions of ancient India, starting with the Edicts of Ashoka, circa 250 BCE.

Birthplace of the historical Buddha[edit]

In a particularly famous Edict, the Rummindei Edict in Lumbini, Nepal, Ashoka describes his visit in the 21st year of his reign, and designates Lumbini as the birthplace of the Buddha. He also, for the first time in historical records, uses the epithet "Sakyamuni" (Sage of the Shakyas), to describe the Buddha.[42]

| Translation (English) |

Transliteration (original Brahmi script) |

Inscription (Prakrit in the Brahmi script) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Heliodorus Pillar inscription[edit]

The Heliodorus pillar is a stone column that was erected around 113 BCE in central India[43] in Vidisha near modern Besnagar, by Heliodorus, an ambassador of the Indo-Greek king Antialcidas in Taxila[44] to the court of the Shunga king Bhagabhadra. Historically, it is one of the earliest known inscriptions related to the Vaishnavism in India.[45][46][47]

| Translation (English) |

Transliteration (original Brahmi script) |

Inscription (Prakrit in the Brahmi script)[44] |

|---|---|---|

|

This Garuda-standard of Vāsudeva, the God of Gods Three immortal precepts (footsteps)... when practiced |

|

|

Middle Brahmi or "Kushana Brahmi" (1st–3rd centuries CE)[edit]

Middle Brahmi or "Kushana Brahmi" was in use from the 1st-3rd centuries CE. It is more rounded than its predecessor, and introduces some significant variations in shapes. Several characters (r̩ and l̩), classified as vowels, were added during the "Middle Brahmi" period between the 1st and 3rd centuries CE, in order to accommodate the transcription of Sanskrit:[52][53]

Independent vowels[edit]

| Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| a /ə/ | ā /aː/ | ||

| i /i/ | ī /iː/ | ||

| u /u/ | ū /uː/ | ||

| e /eː/ | o /oː/ | ||

| ai /əi/ | au /əu/ | ||

| 𑀋 | ṛ /r̩/ | 𑀌 | ṝ /r̩ː/ |

| 𑀍 | l̩ /l̩/ | 𑀎 | ḹ /l̩ː/ |

Consonants[edit]

| Stop | Nasal | Approximant | Fricative | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||||

| Velar | ka /k/ | kha /kʰ/ | ga /g/ | gha /ɡʱ/ | ṅa /ŋ/ | ha /ɦ/ | ||||||||||

| Palatal | ca /c/ | cha /cʰ/ | ja /ɟ/ | jha /ɟʱ/ | ña /ɲ/ | ya /j/ | śa /ɕ/ | |||||||||

| Retroflex | ṭa /ʈ/ | ṭha /ʈʰ/ | ḍa /ɖ/ | ḍha /ɖʱ/ | ṇa /ɳ/ | ra /r/ | ṣa /ʂ/ | |||||||||

| Dental | ta /t̪/ | tha /t̪ʰ/ | da /d̪/ | dha /d̪ʱ/ | na /n/ | la /l/ | sa /s/ | |||||||||

| Labial | pa /p/ | pha /pʰ/ | ba /b/ | bha /bʱ/ | ma /m/ | va /w, ʋ/ | ||||||||||

- ^ a b c d e Cite error: The named reference

RS204was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Daniels, Peter T. (1996), "Methods of Decipherment", in Peter T. Daniels, William Bright (ed.), The World's Writing Systems, Oxford University Press, pp. 141–159, 151, ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7,

Brahmi: The Brahmi script of Ashokan India (SECTION 30) is another that was deciphered largely on the basis of familiar language and familiar related script—but it was made possible largely because of the industry of young James Prinsep (1799-1840), who inventoried the characters found on the immense pillars left by Ashoka and arranged them in a pattern like that used for teaching the Ethiopian abugida (FIGURE 12). Apparently, there had never been a tradition of laying out the full set of aksharas thus—or anyone, Prinsep said, with a better knowledge of Sanskrit than he had had could have read the inscriptions straight away, instead of after discovering a very minor virtual bilingual a few years later. (p. 151)

- ^ Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Calcutta : Printed at the Baptist Mission Press [etc.] 1834. pp. 495–499.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

RHPwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Four Reports Made During the Years 1862-63-64-65 by Alexander Cunningha M: 1/ by Alexander Cunningham. 1. Government central Press. 1871. p. XII.

- ^ Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol V 1836. p. 723.

- ^ Asiatic Society of Bengal (1837). Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Oxford University.

- ^ More details about Buddhist monuments at Sanchi Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, Archaeological Survey of India, 1989.

- ^ Extract of Prinsep's communication about Lassen's decipherment in Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol V 1836. 1836. pp. 723–724.

- ^ Four Reports Made During the Years 1862-63-64-65 by Alexander Cunningha M: 1/ by Alexander Cunningham. 1. Government central Press. 1871. p. XI.

- ^ Keay, John (2011). To cherish and conserve the early years of the archaeological survey of India. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 30–31.

- ^ Four Reports Made During the Years 1862-63-64-65 by Alexander Cunningha M: 1/ by Alexander Cunningham. 1. Government central Press. 1871. p. XIII.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 207.

- ^ Ashoka: The Search for India's Lost Emperor, Charles Allen, Little, Brown Book Group Limited, 2012

- ^ Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Calcutta : Printed at the Baptist Mission Press [etc.] 1838. pp. 219–285.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 208.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

mahadevanwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

spuler1975was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Epigraphia Zeylanica: 1904–1912, Volume 1. Government of Sri Lanka, 1976. http://www.royalasiaticsociety.lk/inscriptions/?q=node/12 Archived 2016-08-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Raghupathy, Ponnambalam (1987). Early settlements in Jaffna, an archaeological survey. Madras: Raghupathy.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Coningham 1996was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ P Shanmugam (2009). Hermann Kulke; et al. (eds.). Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 208. ISBN 978-981-230-937-2.

- ^ a b c Frederick Asher (2018). Matthew Adam Cobb (ed.). The Indian Ocean Trade in Antiquity: Political, Cultural and Economic Impacts. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-138-73826-3.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Salomon 1996, pp. 373–4.

- ^ Bühler 1898, p. 32.

- ^ Bühler 1898, p. 33.

- ^ Daniels, Peter T. (2008), "Writing systems of major and minor languages", Language in South Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 287

- ^ Trautmann 2006, p. 62–64.

- ^ Chakrabarti, Manika (1981). Mālwa in Post-Maurya Period: A Critical Study with Special Emphasis on Numismatic Evidences. Punthi Pustak. p. 100.

- ^ Ram Sharma, Brāhmī Script: Development in North-Western India and Central Asia, 2002

- ^ Stefan Baums (2006). "Towards a computer encoding for Brahmi". In Gail, A.J.; Mevissen, G.J.R.; Saloman, R. (eds.). Script and Image: Papers on Art and Epigraphy. New Delhi: Shri Jainendra Press. pp. 111–143.

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 43. ISBN 9788131711200.

- ^ Evolutionary chart, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 7, 1838 [1]

- ^ Inscriptions of the Edicts of Ashoka

- ^ Inscriptions of Western Satrap Rudradaman I on the rock at Girnar circa 150 CE

- ^ Kushan Empire inscriptions circa 150-250 CE.

- ^ Gupta Empire inscription of the Allahabad Pillar by Samudragupta circa 350 CE.

- ^ Google Noto Fonts – Download Noto Sans Brahmi zip file

- ^ Adinatha font announcement

- ^ Script and Font Support in Windows – Windows 10 Archived 2016-08-13 at the Wayback Machine, MSDN Go Global Developer Center.

- ^ a b c Hultzsch, E. (1925). Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 164–165.

- ^ Avari, Burjor (2016). India: The Ancient Past: A History of the Indian Subcontinent from C. 7000 BCE to CE 1200. Routledge. p. 167. ISBN 9781317236733.

- ^ a b c Greek Culture in Afghanistan and India: Old Evidence and New Discoveries Shane Wallace, 2016, p.222-223

- ^ Osmund Bopearachchi, 2016, Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence

- ^ Burjor Avari (2016). India: The Ancient Past: A History of the Indian Subcontinent from C. 7000 BCE to CE 1200. Routledge. pp. 165–167. ISBN 978-1-317-23673-3.

- ^ Romila Thapar (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. pp. 216–217. ISBN 978-0-520-24225-8.

- ^ Archaeological Survey of India, Annual report 1908–1909 p.129

- ^ Rapson, E. J. (1914). Ancient India. p. 157.

- ^ Sukthankar, Vishnu Sitaram, V. S. Sukthankar Memorial Edition, Vol. II: Analecta, Bombay: Karnatak Publishing House 1945 p.266

- ^ a b Salomon 1998, pp. 265–267

- ^ Brahmi Unicode (PDF). pp. 4–6.

- ^ James Prinsep table of vowels