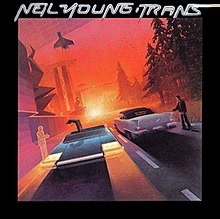

Trans (album)

| Trans | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | January 10, 1983 | |||

| Recorded | September 24, 1981 – May 12, 1982 | |||

| Studio | Modern Recorders, Redwood City, California, Commercial Recorders, Honolulu, Hawaii | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 39:48 (vinyl) 44:20 (CD) | |||

| Label | Geffen | |||

| Producer | Neil Young, David Briggs, Tim Mulligan | |||

| Neil Young chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Trans | ||||

| ||||

Trans is the twelfth studio album by Canadian musician and singer-songwriter Neil Young, released on January 10, 1983. Recorded and released during his Geffen era in the 1980s, its electronic sound baffled many fans upon its initial release—a Sennheiser vocoder VSM201[5] features prominently in six of the nine tracks.

Background[edit]

In 1982, Young left Reprise Records, his record label since his debut album in 1968, to sign with Geffen Records—the label founded and owned by David Geffen, who had worked with Young as manager of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. Young's contract guaranteed him $1 million per album, as well as total creative control over his output.[6]

From late 1980 to mid-1982, Young spent much of his waking hours carrying out a therapy program for his young son, Ben, who was born with cerebral palsy and unable to speak. Neil disclosed to almost no one at the time that he was doing so, or that the repetitive nature of the songs on both the previous album, Re·ac·tor, and this one related to the exercises he was performing with Ben. Work on Trans began in late 1981 as a continuation of Re·ac·tor, with the usual Crazy Horse lineup. But then Young started playing with two new machines he had acquired, a Synclavier and a vocoder. Crazy Horse guitarist Poncho Sampedro recalled, "Next thing we knew, Neil stripped all our music off, overdubbed all this stuff, the vocoder, weird sequencing, and put the synth shit on it."[7]

Young's direction was influenced by the electronic experiments of the German band Kraftwerk, but more importantly he felt that distorting his voice reflected his attempts to communicate with his son. "At that time he was simply trying to find a way to talk, to communicate with other people. That's what Trans is all about. And that's why, on that record, you know I'm saying something but you can't understand what it is. Well, that's exactly the same feeling I was getting from my son."[6][8] Young explained further in a 1988 interview with James Henke for Rolling Stone:

"If you listen to Trans, if you listen to the words to "Transformer Man" and "Computer Age" and "We R in Control," you'll hear a lot of references to my son and to people trying to live a life by pressing buttons, trying to control the things around them and talking with people who can't talk, using computer voices and things like that. It's a subtle thing, but it's right there. But it has to do with a part of my life that practically no one can relate to. So my music, which is a reflection of my inner self, became something that nobody could relate to. And then I started hiding in styles, just putting little clues in there as to what was really on my mind. I just didn't want to openly share all this stuff in songs that said exactly what I wanted to say in a voice so loud everyone could hear it."[9]

Young's first work for Geffen was a group of songs for an entirely different project, Island in the Sun, recorded in May 1982 in Hawaii. According to Young, it was "a tropical thing all about sailing, ancient civilisations, islands and water."[8] Young recalled later, "Geffen thought it was okay, but he didn't think it was good enough."[10]

Instead of recording more new material, Young went back to the synthesizer tracks, actually recorded in the last days of the Reprise contract, and put together an album of songs from the two very different projects, three from Island in the Sun and six of the synthesizer tracks. Young proposed making a video to go with the album that would have clarified what the album was about. "All of the electronic-voice people were working in a hospital, and the one thing they were trying to do is teach this little baby to push a button."[11]

Writing[edit]

While written and recorded for two different projects, in a November 1982 interview with Cameron Crowe, Young links the different songs on Trans as belonging to two different visions of the future of his music: "This album has a split personality...which I think is interesting. Songs like "Like an Inca", that's the future of my music as seen 15 years ago. "Sample and Hold" is the future of my music as seen today. It's more automatic...it's trans-music. That's why I want to call the album Trans."

The album was also influenced by the idea that sometimes the emotions that are the most deeply felt are the ones that are not overtly expressed. As Young observed a world becoming more digital and synthetic, and less outwardly emotional, maybe it was holding more intense emotions inside. He explains in a 1982 French interview:

"I think human emotion, and selling a sad personal story...it's valid, but it's been done so much, who cares? It's like Perry Como, it's like Frank Sinatra, it's way back there now. Now people are living on digital time, they need to hear something perfect all the time or they don't feel reassured everything's okay. Like when you get in the elevator and go up and down and all the numbers go by, everyone knows where they're going. And the drumbeats today, the computerized drumbeats? Everyone is right on the money. Everybody feels good. It's reassuring. I like that. Electronic music is a lot like folk music to me...it's a new kind of rock and roll—it's so synthetic and anti-feeling that it has a lot of feeling... Like a person who won't cry. You know that they're crying inside and you look at them, and they have a stone face, they're looking at you, they would never cry. You feel more emotion from that person than you do from the person who is talking all the time. So I think that this new music is emotional—it's very emotional—because it's so cold...I have my synthesizers and my computers and I'm not lonely."[12]

Young embraced the possibilities of the new synth instruments, and their ability to express a world of new technology and changed human interaction. He imagined a futuristic world of humanoid robots that could aid his son in communicating with the outside world: "I could feel the world changing. I knew I was into something cool when I got the two Sennheiser vocoders to the studio. They enabled me to be a robot, to sing through any thing, present my voice as an envelope to the notes I played with my Synclavier keyboard. I saw the factory, the place where replicas and robots were built to order, the rows of old telephones being operated by feminine appearing robots, beautiful, yet mechanical. I started seeing mechanical nurses in a hospital, who came to help me find a way for my child to speak. I saw Trans for the first time."[13] "Trans was about all these robot-humanoid people working in this hospital and the one thing they were trying to do was teach this little baby to push a button. That's what the record's about. Read the lyrics, listen to all the mechanical voices, disregard everything but that computerized thing, and it's clear Trans is the beginning of my search for communication with a severely handicapped non-oral person."[14]

"Transformer Man" was written about Young's experiences using a Lionel model train set to bond with his son Ben, "hoping that he could learn to communicate through technology".[15]

"Ben and I made a big train layout and I developed a remote control system for Lionel that disabled people like Ben could use. The Transformer is the device that powers the tracks so the train goes. Ben had no control of his hands for fine things like grabbing and moving. He used his head to enable a switch connected by wire to the controller I designed with my friend Ron Milner. The controller wirelessly controlled the train layout. Anything I did on the controller, Ben could reproduce with his head switch until I did something else, then he could do that. It opened a door between us. We had a great time."[16]

The lyrics to "Computer Cowboy (AKA Syscrusher)" tell the story of a cattle farmer who lives a double live as a computer hacker. Young explains the concept in his father Scott Young's book Neil and Me: Computer Cowboy is "a guy's alias. Computer Cowboy is just a front; he has a herd of perfect cows, floodlit fields, even coyotes, But late at night he goes into the city and robs computer data banks of memory systems and leaves his alias, Syscrusher, printed over the information he's lifted. He's a 21st-century outlaw. That's where the big crime is going to be. It's going to move out of Las Vegas and into computer perforations. That's what all the talking in the background of the song at the end is. The computers are all talking to each other, reading what's happening; perforation, protection, security, all those words."[17]

"Mr. Soul" is a re-recording of Young's Buffalo Springfield single. He recorded the song using synthesizers at a time he was in talks with the group to reunite. He explains in a 1986 Rockline interview: "Back in about 1980 or 1981 we were thinking about getting the Springfield together, and as a joke, I made an audition tape for myself so that they'd know I was still kicking. I made "Mr. Soul", but I never did play it for them. That's what I started doing. I made that tape at home with the drum machine and all that, as a sort of joke, as an audition to get in the group. But we never did get together again. Maybe I didn't do a good enough job on that one, I don't know."[18]

Recording[edit]

The tracks with Vocoder and Synclavier were recorded at Young's Broken Arrow Ranch in the fall of 1981. Some of the tracks feature Crazy Horse while others saw Young overdub layers of instruments on his own. Young recalls writing and recording "Transformer Man" in such a manner in a 1982 interview: "It was written to be performed totally in a synthetic sense. I programmed the drum computer myself and performed the rhythms. Programmed the actual sequence and performed all the instruments on it. And all of the voices."[19]

For the later Hawaii tracks recorded in May 1982, Young assembled a group of musicians he had worked with during various stages of his career. He dubbed the group the "Royal Pineapples". Nils Lofgren had previously contributed to After the Gold Rush and Tonight's the Night. Pedal steel guitarist Ben Keith previously appeared on Harvest and Comes a Time. Bruce Palmer had been the bassist in Buffalo Springfield. Ralph Molina is the drummer from Crazy Horse and Joe Lala had previously toured with CSNY. In the fall of 1982, Young embarked on a tour of Europe with this group to promote the album, redubbing the group the "Trans Band".

Release[edit]

After a year of work, Trans was mixed in a hurry because Young was eager to go out on tour (documented in the home video Neil Young in Berlin), and a last-minute change in the running order is evident in the inclusion of a song called "If You Got Love" in the track listing and lyric sheet, even though it is not on the album.[20] Young explains why the song was dropped from the album in an October 1983 Rockline interview: "It was too wimpy! Yeah, I didn't like it. One of those occasions where I changed my mind at the last minute. The record company loves me for that kind of thing."[21] The last-minute mixing was commented on by Young in 1995: "I don't underrate Trans. I really like it, and think if anything is wrong, then it's down to the mixing. We had a lot of technical problems on that record, but the content of the record is great."[22]

The album was slated for a December 1982 release, but Geffen pushed the release into early January, firstly to January 3[23] and then, according to Young, a final date of January 10.[24] According to Jim Sullivan of The Boston Globe, the electronic rock album was considered Young's "most radical move".[25] In an interview with Musician, Young said: "I feel electronic music has replaced the acoustic music that I used to do with my guitar. I can go a lot farther than I've gone… this is just the beginning… I love machines."[25] Portions of several tracks appeared in Young's 1982 feature-length comedy film Human Highway.[26] Trans, along with Young's next Geffen release Everybody's Rockin', formed the basis of a 1983 lawsuit filed against Young by Geffen on the grounds that he had produced deliberately uncommercial and unrepresentative work.[6] Young responded with a countersuit. Both suits were dropped within a matter of months, and David Geffen wound up personally apologizing to Young.

Young had written music videos to accompany the songs on the album, but Geffen rejected the idea, and the videos were never produced. Young would later revisit the idea of producing videos for the album forty years later, with help from collaborator Micah Nelson.[27] "I had created scripts for every song on the album that I wanted to do, especially the computerized voice songs on the album. Now I had a whole story that I wanted to tell. And I had the concepts and everything. And when I tried to sell the concept to the record company, they basically said no, you can't do that; and, that's not what we're doing for videos. And I said well, wait a minute. This is not about what you're doing for videos, it's about what I want to do with my music. And that was the beginning of the end with that record company."[28]

Reception and legacy[edit]

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| The Great Rock Discography | 5/10[31] |

| Pitchfork | 7.8/10[2] |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Village Voice | A−[32] |

Contemporary response[edit]

Trans received mixed reviews from music critics.[25] Barney Hoskyns of NME described Trans as "Young's love song to the future" and noted the electronic style, but felt that he "isn't bothered or bitter enough for this transformation to grow into a vision, a new music". He described the album as "neither very soulful nor very mechanistic" and further panned the use of the vocoder for occasionally making the album recall "the kind of horrid electronic carols you get on your Christmas TV." He wrote: "Where Kraftwerk are concerned less with transformation than with control of information, Young's rather sudden initiation into the new technology merely makes him want to speed up time."[33] Jon Young of Trouser Press felt that, with Trans, Young had accelerated his "Devo" angle" from the earlier album Rust Never Sleeps (1979) into "his own impression of an increasingly mechanized world". However, he felt that Young had settled on the "robotic" style of the album before settling on subject matter, resulting in a "halfbaked yet arresting" minor work.[34] A reviewer for Record Business noted how Young had "gone electronic" with extensive vocoder usage, and added: "How much this will affect the traditional Young sales is unknown but it prompted CBS to delay its release by two months."[35]

However, Rolling Stone reviewer Parke Puterbaugh was favourable to Trans, considering it to be "as drastic a break from career form" as David Bowie's Low (1977) and "twice as surprising, too, because Young, despite his penchant for shifting gears from record to record, has always sunk his roots deep into the good earth, the fertile loam, of the American singer songwriter tradition." He noted the influence of Kraftwerk's Computer World (1981) throughout the album as well as the inclusion of the more traditional Crazy Horse material, resulting in an "intriguing puzzle". He also noted that, as with Rust Never Sleeps, Live Rust (1979) and Re·ac·tor (1981), Trans sees Young "stumping on behalf of the musical New Wave and the technological Next Wave."[20] Robert Christgau of The Village Voice admitted to being confused by the album's "sci-fi ditties" at first, believing them "his dumbest gaffe since Journey Through the Past", but later realised the record was charming and "as tuneful as Comes a Time".[32]

Retrospective[edit]

Retrospectively, William Ruhlmann of AllMusic wrote that, on release, Trans was Young's "most baffling album", and remained for him "an idea that just didn't work". He noted how the vocoder erased the "dynamics and phrasing" of Young's voice, preventing the songs from "being as moving as they were intended to be", and felt that the "crisp dance beats and synthesizers" did not sound contemporary, better resembling early Devo than Kraftwerk.[29] However, Pitchfork reviewer Sam Sodomsky praised Trans for being "an album about affection", which he said boosts its appeal beyond its "mythology" as a "puzzling-if-fascinating failure" in the manner of Bob Dylan's Self Portrait (1970) and Lou Reed's Metal Machine Music (1975). He also noted that, while considered an "aggressive and inscrutable" album, Trans is, "at its heart", a hooky synthesised pop album "informed equally by krautrock and MTV".[2]

According to James Jackson Toth of Stereogum, writing in 2013, the reputation of Trans as a "catastrophic failed experiment" had begun being disputed by "revisionist hipsters, who cite it as a precursor to minimal wave, techno, and countless electronic music subgenres," although disagreed with this himself due to the inclusion of the more traditional rock songs. He did, however, add that much of the album is "incredibly prescient", stating: "the fantastic 'Computer Age' still has no sonic analogue anywhere in music; the proto-electro 'Sample and Hold' invents Daft Punk; a re-recording of 'Mr. Soul' sounds like Thomas Dolby off the meds; and the gorgeous 'Transformer Man' proves that Grandaddy was not the first to outfit artificial intelligence with a heart of gold."[36]

Track listing[edit]

All tracks are written by Neil Young.

Side one[edit]

- "Little Thing Called Love" (3:13)

- Neil Young – guitar, vocal; Nils Lofgren – Wurlitzer electronic piano, vocal; Ben Keith – slide guitar, vocal; Bruce Palmer – bass; Ralph Molina – drums, vocal; Joe Lala – percussion, vocal

- Recorded at Commercial Recording, Honolulu, 5/10/1982.

- "Computer Age" (5:24)

- Neil Young – vocoder, guitar, bass, Synclavier, vocal

- Recorded at Broken Arrow Ranch, 10/29/1981.

- "We R in Control" (3:31)

- Neil Young – vocoder, guitar, Synclavier, vocal; Frank Sampedro – guitar; Billy Talbot – bass; Ralph Molina – drums

- Recorded at Broken Arrow Ranch, 10/14/1981.

- "Transformer Man" (3:23)

- Neil Young – vocoder, guitar, bass, Synclavier, vocal

- Recorded at Broken Arrow Ranch, 12/11/1981.

- "Computer Cowboy (AKA Syscrusher)" (4:13)

- Neil Young – vocoder, guitar, Synclavier, vocal; Frank Sampedro – guitar; Billy Talbot – bass; Ralph Molina – drums

- Recorded at Broken Arrow Ranch, 9/30/1981.

Side two[edit]

- "Hold On to Your Love" (3:28)

- Neil Young – electric piano, vocal; Nils Lofgren – Stringman, vocal; Ben Keith – pedal steel guitar, vocal; Bruce Palmer – bass; Ralph Molina – drums, vocal; Joe Lala – percussion, vocal

- Recorded at Commercial Recording, Honolulu, 5/12/1982.

- "Sample and Hold" (5:09, 8:03 on CD release)

- Neil Young – vocoder, guitar, Synclavier, vocal; Frank Sampedro – guitar; Billy Talbot – bass; Ralph Molina – drums

- Recorded at Broken Arrow Ranch, 9/24/1981.

- "Mr. Soul" (3:19)

- Neil Young – vocoder, guitar, bass, Synclavier, vocal

- Recorded at Broken Arrow Ranch, 9/25/1981.

- "Like an Inca" (8:08, 9:46 on CD release)

- Neil Young – guitar, vocal; Nils Lofgren – guitar, vocal; Ben Keith – slide guitar; Bruce Palmer – bass; Ralph Molina – drums, vocal; Joe Lala – percussion, vocal

- Recorded at Commercial Recording, Honolulu, 5/10/1982.

Personnel[edit]

- Neil Young – vocals, vocoder, guitars, bass, Synclavier, electric piano

- Nils Lofgren – guitars, piano, organ, electric piano, Synclavier, backing vocals, vocoder

- Ben Keith – pedal steel guitar, slide guitar, backing vocals

- Frank Sampedro – guitars, synthesizer

- Bruce Palmer, Billy Talbot – bass

- Ralph Molina – drums, backing vocals

- Joe Lala – percussion, backing vocals

References[edit]

- ^ Gallucci, Michael (29 December 2015). "Why Neil Young Issued the Utterly Bewildering Trans". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Sodomsky, Sam (19 February 2017). "Neil Young: Trans". Pitchfork. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ McPadden, Mike (January 13, 2015). "11 Classic Rockers Who Went New Wave For One Album". VH1. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ Sullivan, Jim (September 6, 1984). "Neil Young". The Boston Globe. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ Dave Tompkins (20102011). How to Wreck a Nice Beach: The Vocoder from World War II to Hip-Hop, The Machine Speaks. Melville House. ISBN 978-1-933633-88-6 (2010), ISBN 978-1-61219-093-8 (2011).

- ^ a b c Clancy, Chris (23 September 2009). "From the Vault: Neil Young". Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ McDonough, Jimmy. Shakey: Neil Young's Biography. New York: Anchor Books, 2003 ISBN 0-6797-509-67, p 552.

- ^ a b Kent, Nick. "I BUILD SOMETHING UP, I TEAR IT RIGHT DOWN: Neil Young at 50." Mojo, December 1995

- ^ Neil Young. By: Henke, James, Rolling Stone, 0035791X, 10/15/92, Issue 641

- ^ McDonough, Shakey, p 556.

- ^ McDonough, Shakey, p 556-557.

- ^ Neil Young Interview Dans Son Ranch de Californie. Antoine de Caunes. August 1982. Www.ina.fr. Accessed December 7, 2023. https://www.ina.fr/ina-eclaire-actu/video/i00006629/neil-young-interview-dans-son-ranch-de-californie-1.

- ^ Neil Young Archives website. July 13, 2019

- ^ McDonough, Jimmy. Fuckin' Up With Neil Young: Too Far Gone. Village Voice Rock & Roll Quarterly. Winter 1989

- ^ Neil Young Archives website post, March 3, 2020

- ^ Neil Young Archives website post, March 18, 2020

- ^ Young, Scott. 1985. Neil and Me.

- ^ Rockline Radio Interview. August 18, 1986.

- ^ Rock On Interview, BBC Radio 1, September 29, 1982

- ^ a b c Puterbaugh, Parke (1983-02-03). "Neil Young Trans Album Review". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- ^ https://sugarmtn.org/ba/pdf.ba/web/ba_viewer.html?file=%2Fba/pdf/ba015.pdf/

- ^ Kent, Nick (December 1995). "I Build Something Up, I Tear It Right Down: Neil Young at 50". Mojo. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ Grein, Paul (January 8, 1983). "January Blitz". Billboard. Vol. 95, no. 1. p. 4. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ "Neil Young Archives". neilyoungarchives.com. Retrieved 2022-07-23.

- ^ a b c Sullivan, Jim (September 6, 1984). "Neil Young". The Boston Globe. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ Human Highway film credits

- ^ "Trans Restored and More." Neil Young Archives. February 12, 2022. Accessed December 21, 2023. https://m.neilyoungarchives.com/news/1/article?id=Trans-Restored-And-More.

- ^ "Singer and Songwriter Neil Young." NPR. Fresh Air. March 25, 2004. https://www.npr.org/2004/03/25/1791701/singer-and-songwriter-neil-young.

- ^ a b William Ruhlmann. "Trans - Neil Young | Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (1997). "Neil Young". Virgin Encyclopedia of Popular Music. London: Virgin Books. pp. 1287–1289. ISBN 1-85227 745 9.

- ^ Strong, Martin C. (2006). "Neil Young". The Great Rock Discography. Edinburgh: Canongate Books. pp. 1233–1235. ISBN 1-84195-827-1.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (March 1, 1983). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ Hoskyns, Barney (January 5, 1983). "Neil Young: Trans". New Musical Express. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ Young, Jon (April 1983). "Neil Young: Trans". Trouser Press. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ "Album Reviews" (PDF). Record Business. 5 (41): 16. December 31, 1983. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ Toth, James Jackson (August 23, 2013). "Neil Young Albums from Worst to Best". Stereogum. Retrieved November 4, 2022.