The Equal Rights Amendment and Utah

From the 1960s through the 1980s, proponents of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) were seeking ratification in each state throughout the United States. Although the Senate approved an unamended version on March 22, 1972, attempts at ratification of the amendment in the state of Utah repeatedly failed.[1] Organizations formed and took positions on both sides of the issue, including the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which was one of the major opponents of the ERA. The Church organized women and other church members in opposition, while also networking with other anti-ERA organizations. The Utah Legislature officially voted down the amendment in 1975.[2] However, Utah still houses a wide variety of organized groups and opinions for and against the Equal Rights Amendment, which remains unratified to the present.[1]

ERA in the United States[edit]

Originally written by Alice Paul and introduced to U.S. Congress in 1923, the Equal Rights Amendment was finally passed in 1972.[3] It was then up to thirty-eight states to ratify the amendment within the next seven years. As explained by Kimberly Voss, a Professor at the Nicholson School of Communication at the University of Central Florida, the ERA could be broken down into three parts:

"Section 1. Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.

Section 2. The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of the article.

Section 3. This amendment shall take effect two years after the date of ratification."[3]

Nationwide, there were coalitions in support of the amendment and against it. While some looked to the ERA as a means to legal equality, which would provide equal economic and academic access, more conservative groups grew wary of the amendment as it could potentially strip away protections that women had under the law. Some arguments against the ERA included the right women had to be exempt from the military draft, anti-unisex bathrooms, and opposition to homosexual marriage.[3]

Anti-ERA Coalitions in Utah[edit]

The Eagle Forum and Phyllis Schlafly[edit]

The nationally involved anti-ERA leader Phyllis Schlafly was also directly involved in the movement against the ERA in Utah. Schlafly organized the National Committee to Stop ERA in 1972, and in 1975 the group became the Eagle Forum.[4] The Eagle Forum became a popular network for anti-ERA women in Utah. Phyllis Schlafly continued to exercise influence among women in Utah. One woman stated that in the International Women's Year convention in Salt Lake City that many attendees carried Phyllis Schlafly material as they voted in opposition to the ERA.[5] Along with the Eagle Forum, other groups also organized in opposition to the ERA, including Humanitarians Opposed to Degrading Our Girls (HOTDOG).[2]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints[edit]

While the Equal Rights Amendment was going through construction and revision during the 1960s and early 1970s, the LDS Church made little to no response. When the House of Representatives passed the bill in 1971, LDS Congressmen responded differently from each other, generally following their party lines.[1] However, as the ERA moved to the states for ratification, the LDS Church began making statements in opposition to the amendment.[6]

In the Ensign in 1971, the President of the Church, Joseph Fielding Smith, made a statement focused on the role of women in society and in the home. He warned that growing media sent messages aimed at tearing down the calling of mothers, which God had ordained.[1] At the general conference of the Church in April 1971, H. Burke Peterson from the Presiding Bishopric stated that the involvement of women in employment would lead to neglect in the family and a focus on worldly gain. N. Eldon Tanner further strengthened the connection between the temptations of Satan and the liberality of women in the October 1973 general conference.[1]

The Relief Society, a women's organization in the church, also continued to spread this anti-ERA message through informal lessons. However, the Relief Society played a more organized part in these politics when the Special Affairs Committee of the LDS Church enlisted Relief Society leaders to work directly in opposition to the amendment. This brought women in Utah directly into the political sphere and made them a central force in the defeat of the ERA.[4]

The Church further established their position by a series of more official statements beginning in 1975 with a Church News editorial. The editorial clarified the separate roles of men and women and claimed that the ERA was unnecessary. While support for the ERA in Utah had initially been about sixty-three percent in November 1974, the official statement from the Church in 1975 led to a drop in support to thirty-one percent in February 1975.[1]

Organization of LDS Women[edit]

As the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints increasingly viewed the fight against the ERA as a broader fight against second-wave feminism, the International Women's Year (IWY) state conference provided the opportunity for Mormon women to mobilize against the feminist movement.[7] Hoping to overwhelm the conference and provide the opinions of many conservative minded women, the church communicated that each ward in the state should send ten conservative women to the conference. The total population for the state conference resulted in 13,867 women.[8]

Coordinated with the help of men on walkie-talkies, these women voted down any proposal without discussion, even some proposals that their goals could have supported.[5] This same process occurred in other states where LDS women resided.[8] Through these efforts to overwhelm the IWY, and other pushes to fight the ratification of the ERA, the Church became a staunch opponent to the passing of the ERA in Utah, and also on a national scale.

Pro-ERA Coalitions in Utah[edit]

Following the example of the President's Commission on the Status of Women, the Governor's Commission on the Status of Women in Utah was organized by Governor Clyde in 1964.[5] While the President's Commission on the Status of Women had initially discreetly formed against the ERA, as members worried that the legislation would threaten protections over working women, Utah's all-women committee focused on general women's issues. They also compiled and issued reports concerning discrimination against women.[2] The committee later worked to persuade the Utah legislature to ratify the ERA, while committee members made and distributed pro-ERA pamphlets.[5]

A more conservative pro-ERA coalition was the National Organization for Women (NOW), which was organized by Betty Friedan in 1966.[2] Members of NOW focused on public opinion as they lobbied for political reform.[1] NOW was also one of the groups that picketed the IWY Convention in opposition to LDS church interference. Other pro-ERA organizations at the convention included the Order of Women Legislators, Women's Democratic Club, Equal Rights Coalition of Utah, League of Women Voters, Equal Rights Legal Fund, Utah Welfare Rights Organization, and the National Abortion and Reproductive Rights Action League.[2]

Some of Utah's universities instituted programs focused on women's studies during this period. One faculty member at Utah State University described this event, stating that despite the university's conservative background and relationship with the LDS church, by 1976–77 around 280 individuals were enrolled in women's studies courses at USU.[5] These university courses were influential in educating on women's rights and the current ERA issues.

Pro-ERA LDS Coalitions[edit]

Another group created in favor of passing the ERA in Utah was Mormons for ERA.[9][10] Founded in 1978, with Sonia Johnson as the first elected president and spokesperson, this group lobbied, created forums which hosted public debates for the ERA, and worked on public relations that gave attention to related issues.[11] Created when just three more states were needed for the ratification of the ERA, Mormons for ERA worked hard within the state of Utah, and Sonia Johnson was even called before the Utah legislation to argue for the amendment. In 1979, when Sonia Johnson was eventually excommunicated from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Mormons for ERA received much more national attention. After the failure of the ratification of the ERA, Mormons for ERA lost followers and contributors and drastically decreased in size. However, the organization still exists today after being revived in 2015.[9][11]

Modern Implications[edit]

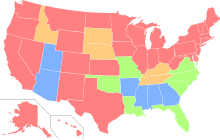

Once the ratification deadline ended in 1982 some still remained hopeful for a future revival of the ERA.[12] Since the 1982 deadline, Illinois and Nevada have both ratified the ERA, leaving the nation one state short from the initial ratification requirements. In the 2019 elections, Virginia elected a majority democratic state congress, and many proponents of the ERA view Virginia as possibly becoming the thirty-eighth state needed to ratify what could become the 28th Amendment to the US Constitution.[13] While thirty-seven states have ratified the amendment, the five states of Nebraska, Tennessee, Kentucky, Idaho, and South Dakota have each since repealed their ratification. What remains in question is how the constitutional conversation around the ERA may proceed if thirty-eight states achieve ratification at some point in their history.[12]

Modern pro-ERA advocates are excited about the possibility of Utah being the last state needed to legally ratify the ERA. Women such as Kate Kelly, Sara Vranes, and Anissa Rasheta are heavily involved with the Utah Mormons for ERA movement, working on the same initiatives as the organization that was established in 1978.[9][14] In the past decade, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has remained neutral about ratification of the ERA in Utah.[9]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Bradley, M.S. (2005). Pedestals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority, and Equal Rights. Salt Lake City: Signature Books.

- ^ a b c d e Derr, Jill Mulvay (2005), "Scholarship, Service, and Sisterhood", Women In Utah History, Utah State University Press, pp. 249–294, doi:10.2307/j.ctt4cgr1m.11, ISBN 9780874215168

- ^ a b c Voss, Kimberly (Fall 2009). "The Florida Fight for Equality: The Equal Rights Amendment, Senator Lori Wilson and Mediated Catfights in the 1970s". Florida Historical Society. 88: 173–208 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b MacKay, Kathryn L. (2005), "Women in Politics", Women In Utah History, Utah State University Press, pp. 360–393, doi:10.2307/j.ctt4cgr1m.14, ISBN 9780874215168

- ^ a b c d e Thorne, A.C. (2002). Leave the Dishes in the Sink. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

- ^ Westwood, Jean Miles (2007-05-01). Madame Chair. Utah State University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt4cgq53. ISBN 978-0-87421-666-0. S2CID 157286338.

- ^ Bradley, M (1995). "The Mormon Relief Society and the International Women's Year". Journal of Mormon History. 21: 106–167.

- ^ a b Quinn, D. Michael (Fall 1994). "The LDS Church's Campaign against the Equal Rights Amendment". Journal of Mormon History. 20: 85–155 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d Fabrizio, Doug (Sep 20, 2019). "Will Utah Be The 38th State to Ratify the ERA?". Radiowest.

- ^ http://archiveswest.orbiscascade.org/ark:/80444/xv98071

- ^ a b "Archives West: Mormons for ERA, 1977–1983". archiveswest.orbiscascade.org. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- ^ a b Thulin, Lila (Nov 13, 2019). "The 96-Year-History of the Equal Rights Amendment". SMITHSONIANMAG.COM.

- ^ Astor, Maggie (Nov 7, 2019). "The Equal Rights Amendment May Pass Now. It's Only Been 96 Years". The New York Times.

- ^ "'Mormon Land': The ERA is back and female members are pushing for it, with their church no longer fighting against it". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved 2019-12-01.