Talk:Fungi in art

| Fungi in art (final version) received a peer review by Wikipedia editors, which on 24 June 2023 was archived. It may contain ideas you can use to improve this article. |

| Fungi in art was nominated as a Art and architecture good article, but it did not meet the good article criteria at the time (February 17, 2023). There are suggestions on the review page for improving the article. If you can improve it, please do; it may then be renominated. |

| This article is rated B-class on Wikipedia's content assessment scale. It is of interest to the following WikiProjects: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Daily page views

|

|

I am wondering if submitting an art piece I made is ok.[edit]

https://fungal.page is a net art page, as a tribute to Wikipedia that takes the form of a mycelium invaded Wikipedia article. I wanted to picture it as a post-human vestige, an artefact invaded by biomorphic figures and spreading typography. I focused on how to create organic ornaments, affecting the encyclopedia’s interface, its typography, the figures and the Wikipedia logo itself. This piece also exists in other forms: A riso fanzine, stickers, poster and open source typeface. The main concept is spreading through media, just like fungi does in a fertile environment. Raphaelbastide (talk) 13:47, 4 January 2023 (UTC)

Hello user:Raphaelbastide thanks for checking. I'd love this page to become a hub for people to share their work and for other to be inspired. Though for sharing information of Wikipedia I believe a reliable secondary source is needed. Is there any news coverage of your work which you can share? For Wikimedia Commons, I believe (but please check!) that it's perfectly fine to upload images of your work. Be aware about the CC-BY license though. Cheers CorradoNai (talk) 17:34, 4 January 2023 (UTC)

- To my knowledge, the project has no news coverage. However, it is exhibited in two different physical art spaces, it is being sold on an independent art shop and has been exposed many times on social media. But I understand why Wikipedia is careful on that subject. Anyway, I love this page. 83.114.12.158 (talk) 15:20, 5 January 2023 (UTC)

- Thanks Raphaelbastide! Let us know when your artwork get press coverage (or of any other relevant artwork) to add to the page! CorradoNai (talk) 05:20, 6 January 2023 (UTC)

GA Review[edit]

The following discussion is closed. Please do not modify it. Subsequent comments should be made on the appropriate discussion page. No further edits should be made to this discussion.

| GA toolbox |

|---|

| Reviewing |

- This review is transcluded from Talk:Fungi in art/GA1. The edit link for this section can be used to add comments to the review.

Reviewer: TompaDompa (talk · contribs) 09:47, 13 February 2023 (UTC)

I will review this. Since the article is extremely lengthy (significantly more than 10,000 words), this will probably take a long time, and I intend to do it piecemeal. I'll ping you when I'm done. TompaDompa (talk) 09:47, 13 February 2023 (UTC)

General comments[edit]

- The article needs a lot of copyediting for spelling, grammar, tone, redundancies, and so on. I have noted several examples below.

- Thanks, I will go through point by point. It seems like a lot, but also very helpful. Thanks for your work. — Preceding unsigned comment added by CorradoNai (talk • contribs) 10:33, 16 February 2023 (UTC)

- The WP:Short description is

Use of fungal materials in artistic works

, which would seem to suggest that the article is about using fungi to create art (e.g. using fungus-based dyes for paintings) rather than depictions of fungi in art (e.g. paintings of fungi). - This article appears to lack a well-defined scope. Paintings of mushrooms, paintings made with fungus-based dyes, paintings made while under the influence of fungal psychedelics, and protecting paintings from mould are very different topics.

- The section headings don't follow MOS:HEADINGS. For instance, "Mushrooms in art" should just be "Mushrooms".

- I see you were told on your talk page to not use date formatting like "2022-12-06" because people may be unsure whether "12" or "06" is the month. Ignore that. That's the ISO 8601 date format, which is internationally standardised, unambiguous, machine-readable, language-independent, and has some other benefits such as sorting chronologically when sorted numerically.

- The images from the 2022 Fungi Film Festival are tagged CC-BY-SA 4.0, which seems a bit odd to me. I was unable to verify this by following the link on the Commons page. I notice you uploaded both images. How did you make that determination?

- There are some MOS:CURLY quotation marks and apostrophes.

- There are several hyphens that should be en dashes, see MOS:ENDASH.

- Where does the representation/showcase/transformation/utilization framework come from? It's referenced heavily throughout the article.

- It would be a lot easier to verify claims in the article if page numbers were always given for book citations.

- There are a lot of repeated links. While it may sometimes be reasonable to repeat a link if the same thing is mentioned much later in the article, several of these are quite close to other identical links.

- The article needs careful copyediting for verb tense.

- Several (sub-)sections start with an excerpt or quote from a poem, song, or similar. This can sometimes be appropriate when used sparingly and judiciously, but it's overused here.

Lead[edit]

- There's a lot of emphatic language here. Examples include

enormous influence

,extremely various and prolific

, andincredibly diverse

. This recurs in the body. - There is an overuse of parenthetical clarifications. This recurs in the body.

entheogenic (psychoactive)

– not synonyms. Either gloss entheogen properly or just say "psychoactive".Atzec

– typo.- The image caption is unsourced.

belonging to the eukaryotes (nucleated or 'higher' organisms)

– what's the relevance of this?being neglected or ignored

– this is an opinion expressed in WP:WikiVoice.Virtually all areas of the arts have been infiltrated by fungi

– overly poetic phrasing.Artists working with fungi are mostly representing (describing), showcasing (symbolizing), transforming, or utilizing them.

– the meaning of this is not obvious. I gather that this is rather important to the overall thesis (for lack of a better word) of the article.The distinction between these art practices and approaches are not clear-cut

– subject–verb disagreement.use them as narrative, rhetorical, stylistic, or stage element

– the last word should be plural.artists using fungi as transformative agent

– the last word should be plural.often explore the topic of transformation, decay, renewal, sustainability, circularity of matter

– is this one topic or several? Either way its ungrammatical.For 'indirect influence of fungi' it is meant the depiction or description of the effect of fungi

– grammar. Also WP:REFERSTO.the creation of art upon influence of fungi-derived substances

– "upon"?could also be considered an indirect influence of fungi in the art

– MOS:WEASEL.Further important aspects of fungi in art

– having the title appear in bold in the fourth paragraph of the lead is way too late. Either include it in the first paragraph (sentence, really) or not at all.

Fungi in art by artistic area[edit]

Traditionally, mushrooms have been the main subject for depiction in the arts [...] the enormous plasticity of fungi enables artists to work with different fungal forms to create very diverse artworks.

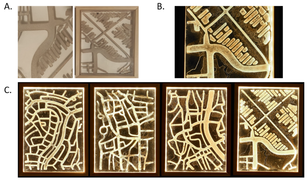

– unsourced.- It would seem to make more sense to have the image (technically images, plural) currently in this section in the lead and vice versa, since the former illustrates the topic's variety and the latter its history.

Artworks representing, showcasing, transforming, and utilizing fungi.

– which is which? The rest of the caption doesn't make that clear.Clockwise from upper left

– I'm fairly certain that's not the case. Clockwise from upper left would end with the bottom left image, but the description seems to end with the bottom right one.1000 BCE-500 AD

– use either BCE/CE or BC/AD, but be consistent. Since the rest of the article uses "BCE" consistently, I would suggest simply replacing "AD" with "CE" here. See also MOS:ENDASH.- The second paragraph consists of 7 sentences for a total of roughly 350 words. There is one source in the middle of the final sentence and five following the final clause. It is very unclear where the majority of the material in the paragraph comes from.

Mushrooms in art[edit]

- The first paragraph goes way WP:OFFTOPIC.

- What is the image of Baba Yaga doing here? The text in this section says nothing about Baba Yaga or Amanita muscaria.

Artists have often represented or described mushrooms as decorative, naturalistic, or symbolic element. In the graphic arts, architecture, sculpture, and literature, artists mostly represented or showcased mushrooms.

– not in the cited sources.mostly represented or showcased mushrooms

– as opposed to mostly doing something else with mushrooms or as opposed to mostly representing/showcasing something else?Currently, contemporary artists are increasingly

– MOS:CURRENT.Currently, contemporary artists are increasingly including mushrooms in their artworks.

– this statement is followed by three sources, two of which verify nothing while the third merely saysToday, according to the curator of a new art exhibition, artists are more interested in fungi than ever before.

The statement in this Wikipedia article is both stronger and more specific than the one made by the source.as for example in

– pleonasm.Early depictions of fungi are petroglyphs from the Bronze Age

– this is a general statement, but was presumably meant to be a specific one.Given the mysterious, seasonal, sudden, and at times inexplicable appearance of mushrooms, as well as the hallucinogenic or toxic effects of some species, their depiction in ethnic, classic and modern art (around 1860–1970) is often associated in Western art with the macabre, ambiguous, dangerous, mystic, obscene, disgusting, alien, or curious in paintings, illustrations, and works of fiction and literature.

– this kind of WP:ANALYSIS categorically needs to come from the sources.Visual artists representing mushrooms have been very prolific throughout history. Whereas examples before the 15th century are rare, examples abound from European visual arts from the 1500 onwards including periods as the Renaissance, the Baroque, Flemish, and Romantic periods.

– not in the cited source.The 'Shaggy ink cap' and the Coprinus comatus

– these two are the same, right?The 'Shaggy ink cap' and the Coprinus comatus and the 'Common ink cap' Coprinus atramentaria mushrooms produce spores by deliquescing (liquefying, or melting) their cap into a black ink, which can be used in drawing, illustration, and calligraphy.

– this could and should be condensed. It contains a lot of unnecessary details.Protocols to produce the 'mushrooms ink' can be found online.

– WP:NOTHOWTO.as in petroglyphs representing mushroom-headed people discovered near the Pegtymel River (Siberia)

– already mentioned.around the world, including in western and non-western works

– rather odd phrasing that doesn't provide much information. "Around the world" would seem to imply basically everywhere. Why elaborate further? Why use "western and non-western", specifically? Seems like WP:Systemic bias to me.more mushrooms are present in artworks from cultures considered to be mycophiles

– that hardly seems surprising. I might even expect this to be true by definition.considered to be mycophiles

– by whom?- Does the entire first paragraph in the "Paintings, tapestries, and illustrations" subsection come from the source cited at the end?

collects and describe

– grammar.During the Victorian era, numerous scientists drew accurate illustrations of fungi, blurring the border between mycology and the arts.

– unsourced.- The Registry of Mushrooms in Works of Art is mentioned three separate times in different paragraphs.

Art periods and artists are categorized as follows in the registry:

– so what? This is clearly out of proportion in this article. It might belong in an article about the registry itself, but not here.Notable examples

– see MOS:Words to watch.Notable examples of visual artists depicting mushrooms and how they contributed to both mycology and the arts are:

– how were these examples chosen? This is also a bad use of a list in a prose article.how they contributed to both mycology and the arts

– contributions to mycology are WP:OFFTOPIC if they don't relate to the arts. The Beatrix Potter entry is an example of going off-topic like this.Hundreds of his paintings have been digitized by the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel (Philadelphia)

– superfluous detail.- The Charles Tulasne entry is entirely unsourced.

He is known for his excellent illustrations

– that's an opinion.174 13" by 15"

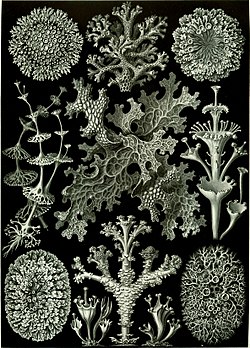

– clunky phrasing. This notation is also to be avoided, see MOS:INCH.- The Ernst Haeckel entry is entirely unsourced. It should also be "Haeckel" rather than "Häckel" per the linked article (the article on German-language Wikipedia likewise uses ae rather than ä, so this does not seem to be an Anglicization of the spelling).

A countless number [...] abound

– pleonasm.Non-fiction books about fungi, especially those involving identification of fungi, includes photographs of fungal species and their fruiting bodies.

– subject–verb disagreement.Work of literary fiction

– grammar.Work of literary fiction involving mushrooms and fungi are often linked to [...]

– I'm guessing this is meant to say that the mushrooms and fungi, rather than the fiction itself, are linked to that stuff.often linked to infection, decay, toxicity, mystery, fantasy, and ambiguity, and thus have mostly a negative connotation

– could you provide a quote from the source that verifies this?In line with the assumption

– whose assumption?During the Victorian era, fungi started to acquire a more playful, childish, or jolly role in works of literary fiction.

– not in the cited source.Several renowned authors have used fungi as plot device.

– MOS:PUFFERY.These include Percy Shelly, Lord Alfred Tennyson, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, D.H. Lawrence, H.G. Wells, Ray Bradbury, and more.

– "These include" means that the list is non-exhaustive, making "and more" redundant. I also find it questionable that it's necessary to give this many examples.Lord Alfred Tennyson

– I've heard this person referred to as "Alfred, Lord Tennyson", "Lord Tennyson", "Alfred Tennyson", and often just plain "Tennyson", but never "Lord Alfred Tennyson". I don't know if it's strictly speaking incorrect, but it sticks out.Percy Shelly

– typo.Fungi have been a common trope in the science fiction, horror, supernatural, fantasy and crime fiction genres. Fungi have a long tradition in science fiction.

– repetitive.In Ray Bradbury's Come into My Cellar

– the titles of short stories are presented in "quotation marks", not italics.alien invasors

– typo.Fungi have been a common trope in the science fiction, horror, supernatural, fantasy and crime fiction genres. [...] Crime and detective writer Agatha Christie has repeatedly used mushrooms as murder weapon in her crime fiction.

– does all of this come from the source cited at the end?A non-exhaustive list of fictional stories involving mushrooms is given below:

– why? This is not TV Tropes.The quarterly periodical FUNGI Magazine runs a regular feature called Bookshelf Fungi reviewing fiction and non-fiction books on fungi.

– unsourced.In Western culture poetry, as in literature, fungi are historically associated with negative feelings or sentiments, although, together with the rising popularity of fungi, this trend might hold less true in recent years.

– this kind of WP:ANALYSIS categorically needs to come from the sources.The poem The Mushroom (1896) by Emily Dickinson is unsympathetic towards mushrooms. American author of weird horror and supernatural fiction H. P. Lovercraft created a collection of cosmic horror sonnets with fungi as subject called Fungi from Yuggoth (1929–30). Margaret Atwood's poem Mushrooms (1981) explores the topics of the life cycle and nature.

– not in the cited source.True to the observation that Asian cultures are mycophilic, several hundreds of Japanese haiku have as their subject mushrooms and mushroom hunting

– not compliant with WP:NPOV. This is endorsing a particular viewpoint. This needs to be given WP:INTEXT attribution to the source that says that (1) Asian cultures are mycophilic and (2) this is reflected in haiku writing.Numerous haiku have been recently translated into English.

– superfluous detail, and MOS:RECENT.fungi have had an conspicuous influence in mythology

– "conspicuous"?across various latitudes, civilizations, and historical epochs

– why latitudes?has arguably contributed

– MOS:EDITORIALIZING.The distinction between literature, folklore, and myth is not always clear cut, and occasionally open to interpretations.

– who says so in this context?Some writers argue that fungi have inspired numerous myths, and vice versa that many myths can be re-interpreted through the lens of fungal ecology.

– do some authors say the former and others the latter, or do the same people say both? This also needs to be sourced.Juda Iscariot

– typo.Occasionally, the involvement of fungi in myth and folklore is driven by allegory, cultural practices, or popular interpretations.

– Unsourced.For example, given the cultural relevance and prevalence of fermented (alcoholic) beverages throughout history, there are numerous deities associated with wine and beer, which can be regarded as an indirect effect of fungi in the arts.

– according to whom? This could also be condensed by removing the superfluous "given the cultural relevance [...]" part.Fungi (yeasts) play a conspicuous role in several religions, for example through fermentation (e.g. wine) and leavening (e.g. bread).

– this overlaps significantly with the preceding sentence and could be merged with it. It also needs to be sourced.According ton

– typo.In the Parable of the Leaven, one of the Parables of Jesus, the growth of the Kingdom of God is akin to the leavening of bread through yeast. [...] However, yeast is associated with corruption in other passages of the New Testament

– this is interesting, but it needs to be sourced to reliable sources making the same point in the context of the topic of this article, i.e. fungi in art.[Mead] has played an important role in the mythology of some peoples. In Norse mythology, for example, the Mead of Poetry, crafted from the blood of Kvasir (a wise being born from the mingled spittle of the Aesir and Vanir deities) would turn anyone who drank it into a poet or scholar.

– unsourced.As one of the evidences they provide

– grammar.as a way to increase mushroom harvesting

– as a way to increase the amount harvested, presumably. Not the amount of work done harvesting.where since recently

– MOS:RECENT.researchers are investigating the effect of electric voltage on mushroom sprouting, showing positive correlations with some species

– WP:OFFTOPIC.According to several interpretations, the legendary figure of Santa Claus is heavily influenced by the fly agaric

– not at all what the source says. Millman saysSanta Claus: A celebrated gift giver who may have the fly agaric (Amanita muscaria) as one of his ingredients.

That's just one interpretation—Millman makes no mention of any other one—and there's a significant difference between "is heavily influenced by" and "may have as one of the ingredients".anecdotal evidences

– grammar. This is also not anecdotal evidence.The connotation was dispregiative

– dispregiative?There is a conspicuous corpus of literature

– odd and rather, yes, conspicuous phrasing.Although these books are non-fictional, the works are often excellent examples of storytelling and tinkering

– that's an opinion stated in WP:WikiVoice.and are a fundamental source

– that's also an opinion.the growing do-it-yourself community

– why describe it as "growing"?These works are not only an important source but also a way for artists to converge and experiment with fungi.

– unencyclopedic in tone. Comes off as promotional. Persuasive writing, really. Also unattributed opinion.The book [...] offers insights

– definitely way too promotional.Some books proposed speculative or disputed theories on the cultural influence of fungi throughout history, like The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross by John Allegro, and were received critically by fellow mycologists.

– why is this here? Basically every field will have some degree of disagreement within it. Is there any strong reason to bring this particular instance up?The online book club 'MycoBookClub' discusses monthly a selection of mostly non-fiction books on fungi on Twitter.

– why bring up an online book club?Authors of non-fictional books about fungi are often pioneers

– MOS:PUFFERY.contribute to the increased popularity, popularisation [...]

– contributing to the increased popularity of something and contributing to the popularisation of the same thing are just two different ways of saying the same thing, making this redundant.- I daresay using seven references in a row here is WP:Citation overkill.

Adaptations of literary fiction into motion pictures follow similar tropes present in science fiction, horror, supernatural, and crime fiction genres.

– is that from the cited source? At any rate, this seems rather unsurprising and not necessarily worth mentioning.- Is it necessary to have yet another mention of the Pegtymel petroglyphs in this section? Much of the information is repeated. It seems more reasonable to mention that they have been the subject of a documentary at their first mention, if the documentary needs to be mentioned at all.

the eponymous petroglyphs

– how are they eponymous? The documentary is called Pegtymel, the name of the river.commercially successful

– wholly irrelevant MOS:PUFFERY.released on Netflix

– irrelevant detail.renowned mycologist

– MOS:PUFFERY.the intriguing world of fungi

– that's a subjective assessment.presents the intriguing world of fungi [...] with the use of narration, time-lapse photography, and interviews

– these are all rather standard techniques in documentary filmmaking. Is there any particular reason to mention this here?The documentary covers fungi and not only mushrooms.

– conspicuous phrasing. This rather forcefully implies that this is unexpected and a positive.Recently, new film festivals

– MOS:RECENTLY.Screening ar online or at specific venues.

– I'm not entirely sure what this is intended to say, but it appears to have been mistyped.Most notably

– according to whom? This is unattributed opinion stated in WP:WikiVoice.Most notably are the Fungi Film Festival [...]

– grammar.Radical Mycology author Peter McCoy

– is this meant to say that McCoy is the author of a work with the title Radical Mycology, or that McCoy is an author within the field of radical mycology? Either the capitalization or lack of italics is wrong.often present at the 2022 Fungi Film Festival

– often present at a single event? Is this meant to say that it is present in many entries in the 2022 event or that it is recurring in different years?The commercially successful 2019 documentary Fantastic Fungi [...] Topics and themes often present at the 2022 Fungi Film Festival are personification of mushrooms, experimental/conceptual representation of fungal forms, and utilization of mushrooms for their (hallucinogenic) properties.

– not in the cited source.drew inspiration from Terence McKenna's 'Stoned Ape Theory'

– which is what, exactly? This is not particularly informative.In the Belgian comic franchise The Smurfs, the characters with the same name

– poor phrasing. Really, this could all be replaced with just "The Smurfs".American fantasy and science fiction comic book artist Frank Frazetta illustrated the cover image of the 1964 edition of the novel The Secret People (1935) by John Beynon (pseudonym of John Wyndham), in which fictive 'little people' inhabit areas with giant mushrooms.

– presumably the last clause applies to the novel rather than the cover image, so why mention the cover image at all?Dave Gibbon's comic strip Come into My Cellar is based on Ray Bradbury's short story with the same name.

– Bradbury's story is mentioned above, so this seems superfluous.Game designer Shigeru Miyamoto acknowledged Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland as direct influence for the 'super mushroom' in developing Nintendo's Super Mario video game.

– this really buries the lead. The important part is surely the mushrooms appearing in the game, with the Alice in Wonderland inspiration of secondary importance here.The celebrated video game franchise The Last of Us

– MOS:PUFFERY.wiped off humanity

– wiped out humanity, presumably.turning infected into zombies

– this is missing a definite article or a noun.Further video games where mushrooms appear as health-boosting collectibles or poisonous mushrooms

– that's an odd framing. Also poorly phrased.Zelda: Breth of the Wild

– typo.A music gerne

– typo.A music gerne called Fungi from the British Virgin Islands is defined as a mixture of many styles and instruments.

– does this actually have anything to do with fungi, the biological kingdom? According to the linked article, that's not where the name comes from.The Czech composer and mycologist Václav Hálek (1937-2014) claimed to have created numerous musical works inspired by fungi.

– claimed?Václav Hálek

– it is inappropriate to link to a Wikipedia article in a different language without making that obvious to the reader. Use Template:Interlanguage link instead, like this: Václav Hálek.American composer John Cage (1912-1992) was an enthusiastic amateur mycologist and co-founder the New York Mycological Society.

– what's the relevance of this? Being a composer and an amateur mycologist does not in itself imply a connection between the to.'Fossora' is the feminine declination of the Latin fossore, meaning "she who digs".

– what's the relevance of this?'Fossora' is the feminine declination of the Latin fossore, meaning "she who digs".

– the cited source says "it is a word i made up".feminine declination

– the word you're looking for is declension.The Czech composer and mycologist Václav Hálek [...]

– already mentioned.A non-exhaustive list of songs inspired by mushrooms (fungi) is given below:

– why? This is WP:NOTTVTROPES.made of transparent or opaque glass, although coloured glass was used when needed

– that seems to cover most bases. What am I missing?Fungi enter cuisine mostly as fruiting bodies (mushrooms).

– is that really true? Yeasts and molds also have very central roles in cuisine.mushrooms can be considered a novel culinary trend

– according to whom?The 'Shaggy ink cap' mushroom Coprinus comatus produces spores by deliquescing (liquefying, or melting) its cap into a black ink.

– already mentioned above.it is used in Mexico as the delicacy huitlacoche [...] in Mexico they are highly esteemed as a delicacy, where it is known as huitlacoche

– extreme redundancy within the same paragraph, both in terms of repeated information and repeated links.Huitlacoche is a source of the essential amino acid lysine, which the body requires but cannot manufacture. It also contains levels of beta-glucans similar to, and protein content equal or superior to, most edible fungi.

– why discuss the nutritional value here?- The link to White Rabbit should go to White Rabbit (song).

Current research on psychoactive mushrooms shows promises for the treatment of mental-health ailments like chronic depression and anxiety.

– why on Earth is this article making biomedical claims?A 'mushroom counterculture' has been often fuelled by eccentric, unorthodox, and unfalsifiable hyphotheses and interpretations of the influence of (hallucinogenic) mushrooms in culture developments [...]

– who is making this assertion? I seriously doubt the cited source by McKenna (who is used as an example of this) says this.McKenna hyphotesis

– double typo.McKenna hyphotesis has been controversial

– MOS:CONTROVERSIAL.

Mycelia or hyphae in art[edit]

- The first paragraph goes way WP:OFFTOPIC.

- This image has already been used in a collage elsewhere in the article.

Hyphae are the most metabolically active structures of fungi, secreting high amounts of digestive enzymes in the surrounding environment to consume the growth substratum, as well as bioactive metabolites, including substances used in modern medicine (antibiotic and antimicrobial drugs). Hyphae and mycelia grow by extension and branching, and fungi forming those structures are often referred to as 'filamentous fungi'.

– relevance?Mycelia and hyphae have seldomly been represented, showcased, transformed, or utilized in the traditional arts due to their invisible, ignored, and overlooked lifestyle and appearance.

– source?have seldomly been represented [...] due to their invisible, ignored, and overlooked lifestyle and appearance.

– they have seldomly been represented because they are ignored and overlooked?lifestyle and appearance

– "lifestyle"?enjoying increasing visibility, marketing, commercialization, and endorsement from celebrities

– and Wikipedia articles like this one? Joking aside, this comes off as promotional.In literature and fiction, hyphae and mycelia are considered (if at all) for their intrinsic properties of decomposition, contamination, and decay.

– source?The filamentous, prolific, and fast growth of hyphae and mycelia (like moulds) in suitable conditions and growth media often makes these fungal forms good subject of time-lapse photography.

– according to whom?imagery allegedly inspired by ergotism

– if the qualifier "allegedly" is necessary, this doesn't belong. If it isn't necessary, it should be removed. Either way, this needs to be sourced.- The coverage of ergotism goes way WP:OFFTOPIC, arguably into WP:COATRACK territory.

Whereas non-fiction books about fungi often (if not always) include hyphae and mycelia, examples of hyphae and mycelia in literary fiction are much rarer in comparison to mushrooms and spores. When these fungal forms are included in work of fiction, they are often associated with elements of rot and decay.

– unsourced.fast, radial growth (also called isodiametric growth, that is, with same speed and size in all directions)

– this is mentioned elsewhere and could be condensed significantly even if it weren't.mycelia and hyphae are often used as time-lapse photography to present filamentous growth and/or decay

– source?- IMDb is not a WP:Reliable source, see WP:IMDb, WP:RS/IMDb and WP:Citing IMDb.

its growth plasticity (e.g. the ability to take virtually any shape upon being cast in a desired form)

– I believe "i.e." is intended here, rather than "e.g."vernacularly called

– conspicuous phrasing. The usual phrase is "commonly called", or sometimes "colloquially called". A simple "also called" would also do the trick here.the Stradivarius violin

– there are multiple Stradivarius violins, not just one.produce sounds close to those from the Stradivarius violin

– this is an WP:EXCEPTIONAL claim, and as such needs exceptional sourcing.mixd into

– typo.Current collaborations

– MOS:CURRENT.Luxury fashion brands like Adidas, Stella McCartney, and Hermès are introducing vegan alternatives to leather made from mycelium.

– comes off as promotional.Remarkable evidence

– MOS:FLOWERY.Mycologist Paul Stamets famously wears a hat made of amadou.

– famously? That needs to be backed up with reliable sources saying so, and I daresay https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mPqWstVnRjQ is not a WP:Reliable source.Fungi has

– subject–verb disagreement.Fungal mycelia are used as leather-like material (also known as pleather, artificial leather, or synthetic leather), including for high-end fashion design products.

– already covered above.cruelty-free

– that's a value-laden WP:LABEL.A patent study covering 2009-2018 highlighted the current patent landscape around mycelial materials based on patents filed or pending.

– relevance?Mushrooms are traditionally the main form of fungi used for direct consumption in the culinary arts.

– this is a subtly but significantly different claim than the one I questioned above. This version is much less dubious. That being said, it's not in the cited source.an enormous variety

– inappropriately emphatic language.beverages such as beer, wine, sake, kombucha, coffee, soy sauce, tofu, cheese, or chocolate

– not all of these are beverages.just to name a few

– inappropriately informal. Also redundant to "including".The Michelin-star restaurant The Alchemist in Copenhagen

– mentioning the Michelin star comes off as promotional.Copenhagen (Danemark)

– Denmark.'mycelium-based seafood'

– this quote does not appear in the cited source.'mycelium-based bacon.'

– this quote does not appear in the cited sources. See also MOS:LQ about punctuation placement.Hapha and mycelium

– typo.gets increased attention in the contemporary art due to its growth and plasticity, and is occasionally the starting point for artworks in the contemporary art

– repetitive phrasing.the biotechnology-relevant fungus Aspergillus niger

– why gloss it like that?freely available at www.color.bio

– I would suggest you review Wikipedia's policy on WP:External links.

Spores in art[edit]

- The first paragraph goes a fair amount WP:OFFTOPIC.

Examples of fungal spores in the arts are rare due to their invisibility and difficulties to treat and manipulate as working matter.

– source?Notable exceptions are so called 'spore prints,' or glass sculptures by mycologist William Dillon Weston (1899-1953) representing magnified microfungi and spores (ascospores, basidiospores).

– this is a general statement, but was presumably meant to be a specific one.Notable exceptions

– MOS:NOTABLE.'spore prints,'

– MOS:LQ.Often, fungal spores are employed as an agent of infection and decay in literature and the graphic arts, whereas recently they are increasingly used in the contemporary art in a positive or neutral way to reflect about processes of transformation, interaction, decay, circular economy, and sustainability.

– the cited source doesn't actually say this.a flat, white or coloured surface

– this is ambiguous. Does it refer to (1) a surface that is flat, and is additionally either white or coloured, or (2) a surface that might be flat, might be white, and might be coloured, but always one of those three?spores prints

– grammar.Whereas non-fictional books about fungi cover spores in the context of fungal spore formation, dispersal, harvesting, or germination, works of literary fiction involving spores are generally linked to infection and decay, and thus have mostly a negative connotation.

– source?In stories where mushrooms are perceived or represented as threat, spores fulfill the same role.

– source?In the short story Come into My Cellar, by Ray Bradbury, for example, spores are depicted as an alien invasion.

– see my earlier comments about this story.The critically acclaimed and commercially successful video game franchise

– MOS:PUFFERY.by Sony Computer Entertainment

– relevance of this detail?(Part I, released in 2013; downloadable content adds-on The Last of Us: Left Behind, released in 2014; Part II, released in 2020)

– seems like unnecessary detail.- There is a lot of detail about The Last of Us. Too much. Approaching WP:COATRACK territory.

An important part of the plot of The Last of Us game franchise revolves around vaccines against the fungal disease; as opposed to vaccination against viral and bacterial pathogens, research on vaccines for human fungal diseases lags behind, with currently no vaccine available against human fungal pathogens.

– this goes way WP:OFFTOPIC.The Last of Us Part II has been awarded best video game of 2020 by The Game Awards.

– entirely irrelevant.A television adaptation by HBO starring among others Pedro Pascal as Joel, Bella Ramsey as Ellie, and Nick Offerman as Bill, is due in January 2023.

– outdated.A television adaptation by HBO

– why does it matter that it's by HBO?starring among others Pedro Pascal as Joel, Bella Ramsey as Ellie, and Nick Offerman as Bill

– the character names mean nothing to readers unfamiliar with the franchise. Who stars in the show is also not relevant to the topic of this article.The comic strip by Dave Gibbon Come into My Cellar is based on Ray Bradbury's short story with the same name, where fungal spores are an alien entity taking over humanity by mind control, especially of children obsessed with growing mushrooms in their home basement.

– again with this story. See my earlier comments about it.An adaptation into Italian appeared for the famous comic series Corto Maltese in 1992 with the name Vieni nella mia cantina.

– how does this relate to the topic of this article? It's presented entirely devoid of explanatory context.

Yeasts, moulds, or lichens in art[edit]

- The first paragraph goes a fair amount WP:OFFTOPIC.

in the hands of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae

– "in the hands of" is inappropriate here (and when the same phrasing recurs later in the same paragraph). See MOS:CLICHE.Blue cheese is cheese [...]

– you don't say? The second "cheese" is redundant.Naturalists illustrating their observations often created remarkable work of arts.

– that's an opinion.- Does the entirety of the second paragraph come from the two sources cited at the end of it?

extremely common

– inappropriately emphatic language.contributed enormously

– inappropriately emphatic language.which is but one of

– not particularly encyclopedic in tone.Other testimonies of the indirect effect of yeasts in the arts are the numerous deities and myths are associated with wine and beer.

– anacoluthon.The field of ethnomycology focuses more on the influence of psychoactive fungi on human culture rather than on aspects such as medicine, food production practices, or cultural influence in the arts.

– going a bit WP:OFFTOPIC.Time-lapses photography

– grammar.Aside from various illustrations, lichens are very seldomly represented in the arts to their slow growth as well as their frailty towards maniputation.

– seems to be missing a "due".maniputation

– typo.Notable examples

– MOS:NOTABLE.Notable examples of yeasts, moulds or lichens in the arts include:

– why the list? This is not TV Tropes.Ernst Häckel

– see my earlier comment about the name. This is also unsourced.dying substances

– I think this is meant to say "dyeing substances", i.e. substances used as dyes.In the science fiction novel Trouble with Lichen (1960) by John Wyndham, a chemical extract from a lichen is able to slow down the aging process, with a profound influence on society

– unsourced.In Stephen King's horror short story Gray Matter (1973), a recluse man living with his son drinks a 'foul beer' and slowly transforms into an inhuman blob-like abomination that craves warm beer and shun light, and transmutes into a fungus-like fictional creature

– unsourced.a comedy which won numerous awards at international film festivals

– unnecessary detail, comes off as promotional.involves 'a young trombone player [...] trying to open an impossible bottle of wine [...] and some mold gets in his way

– unpaired quotation mark.In so-called 'mold paintings,' surfaces of buildings or sculptures are intentionally overgrown with moulds to create visually appealing effects

– unsourced.In so-called 'mold paintings,' surfaces of buildings or sculptures are intentionally overgrown with moulds to create visually appealing effects

– stick to spelling it either "mold" or "mould". Switching back and forth looks unprofessional, especially when (as here) within a single sentence.The musical provides freely available teaching resources

– we are not their PR team. See WP:NOTPROMO.however, during baking, microorganisms present in dough are most probably heat deactivated and thus harmless.

– not in the cited source. This violates WP:NPOV by engaging in a dispute rather than describing it.the homemade yogurt relied on the fermentation properties of lactic acid baceria (e.g. lactobacilli), rather than yeasts (fungi)

– that would make it out of scope for this article then, now wouldn't it?unlike bread, yogurt is a culture of living microorganisms

– not in the cited source.The praxis is thus considered a food hazard by the US Food and Drug Administration.

– that's not actually what the source says. It says that the end product would be considered adulterated, and it gives a completely different reason as to why that is.an artwork which wants to make the audience reflect about the role of yeast biotechnology to confront global issues of contemporary society

– that's an appropriate way to describe it for the artist, or an exhibition, or the news media, but it's not appropriate for Wikipedia.aestic objects

– typo.Physarum polycephalum is a slime mould (myxomycete) and not a fungus

– that would make it out of scope for this article then, now wouldn't it?Due to its complex problem-solving abilities, the slime mould is used to mimic or investigate human behaviours.

– unsourced.Physarum polycephalum has been shown to exhibit characteristics similar to those seen in single-celled creatures and eusocial insects. For example, a team of Japanese and Hungarian researchers have shown P. polycephalum can solve the shortest path problem. When grown in a maze with oatmeal at two spots, P. polycephalum retracts from everywhere in the maze, except the shortest route connecting the two food sources.

– what on Earth does this have to do with the topic of this article, fungi in art? This is neither a fungus nor art.

Indirect influence of fungi in art[edit]

- This entire section is unsourced.

This indirect influence of fungi in the arts can be broadly classified into three categories:

– you really need to get this WP:ANALYSIS from the sources.Of notable example

– MOS:NOTABLE, grammar.insofar part of their artworks have been likely created under the influence of fungal substances while they also depict the effect of fungal metabolites

– this is rather difficult to parse.

Preservation of artworks against fungal decay[edit]

- This seems like a completely different topic that is not within the scope of the article. Treating this as a different aspect of fungi in art is basically an equivocation.

represent a treat

– a threat, presumably.damage them by means of mechanical, chemical, or aesthetic damage

– damage them by means of damage? That's rather redundant.damage them by means of mechanical, chemical, or aesthetic damage

– mechanical and chemical damage would seem to be the processes by which aesthetic damage occurs. This is mixing apples and oranges, in other words.An area of applied research focuses on limiting the growth, harm, and health hazard of mould growing inside buildings, often referred to as 'microbiology of the built environment.'

– this doesn't seem to be related to art at all?A recent study

– MOS:RECENT.xerophilic (tolerant to desiccation)

– not the most helpful gloss as it still uses rather technical language. If I had to gloss it I might say "can withstand dry conditions".Microorganisms like fungi are not only considered in the preservation of artworks do due their decaying and contaminating properties.

– this appears to have been mistyped. I'm not entirely sure what it was meant to say.

Further explorations, applications, and fostering of the 'fungal arts'[edit]

Artists and scientists jointly defined a framework for fruitful collaborations between (fungal) science and the arts.

– this uses a large number of words to convey very little information.The generally low visibility of fungi (other than mushrooms) in the arts can be correlated with the general knowledge and research on fungi, both of which lag behind in comparison with other life science disciplines

– this sounds a lot like WP:Original research to me. If it comes from the sources it needs WP:INTEXT attribution, and if it doesn't it needs to be removed.Mycology was named as a natural science discipline of its own in 1836 only

– that doesn't strike me as particularly late, actually. It predates e.g. bacteriology and virology significantly, does it not? For that matter, it predates evolutionary biology. From what I can gather, it also predates ecology.the fungi kingdom Funga was defined in 1969 only

– redundant phrasing aside, the kingdom is called Fungi.and even today conservation efforts on fungal biodiversity lag behind in comparison to those of species in other kingdoms of life like animals and plants.

– overly argumentative in tone.Currently, in the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List of Threatened Species, only over 500 fungi are included, in comparison to over 58,000 plants and 12,000 insects.

– I am unable to verify this from the cited source, though I'm sure the relevant information can be found somewhere on the webpage. However, this is just raw data. The phrasing rather forcefully implies that the number of fungi should be higher, but that's an assessment that unequivocally needs to come from WP:Reliable sources. Also MOS:CURRENT.- Pretty much the entire first paragraph comes across as an effort to WP:Right great wrongs.

Several artistic explorations of fungi have as background, intention or goal the development of sustainable solutions to current environmental issues, or aim at raising awareness on these topics.

– this is an example of a sentence that uses far more words than necessary to convey the point. Without even restructuring the sentence, rephrasing it as "Several artistic explorations of fungihave as background, intention or goalrelate to the development of sustainable solutions tocurrentenvironmental issues, or aim at raising awareness on these topics." (resulting in "Several artistic explorations of fungi relate to the development of sustainable solutions to environmental issues") would reduce the length of the sentence almost by half. It could be condensed even further if the sentence structure were adjusted. This and the following sentence—Several artistic explorations of fungi have as background, intention or goal the development of sustainable solutions to current environmental issues, or aim at raising awareness on these topics. These endeavors often involve a multi-disciplinary approach between artists and fungal practitioners, and transform or utilize fungi for the desired goal.

—together consist of 49 words, but could be rewritten with as few as 18—"Sustainable solutions to environmental issues is a recurring theme, often used by artists working together with fungal practitioners."—while still conveying the main points (not that this is necessarily the best way to do it). Sometimes less is more, and this article suffers from a lack of brevity.Occasionally, a commercial outcome beyond the purely artistic approach or experimentation is striven for or achieved.

– this is not entirely relevant, and kind of sounds like PR-speak ("we want to make money, but are embarrassed to admit it"),these approaches fall often within the realm of circular economy.

– it's good to have links for terms like this that many readers will not be familiar with, but this is an instance where I think it also needs to be explained in the context where it appears.Patents to intellectually protect the technological developments are often filed.

– I think this goes without saying.- I find it extremely dubious that four pictures of MY-CO SPACE is called for. It comes of as very promotional. One of them is also used elsewhere on the page.

Examples of the use of fungi in sustainability approaches fall within production of fungus-based materials for personal use (vegan leather, house furniture) or as construction materials, or for alternative burial practices (bioremediation), just to name a few.

– "Examples [...] fall within [...] just to name a few" is a very redundant phrasing. "Just to name a few" should also be avoided for reasons of being unencyclopedic in tone.Fungus-derived material from mycelium are being developed

– grammar.Fungus-derived material from mycelium are being developed to create artificial leather for high-end fashion products

– this is the third(?) time this is mentioned in the article.and hold promises to be a sustainable alternative to animal-derived leather

– extremely promotional in tone.by international artists

– what does "international artists" mean? It comes off as a euphemism for "foreigners".More and more artists work with fungi [...]

– is that "more and more artists" (an increasing number of artists) or "more and more, artists [...]" (to an increasing extent, artists [...])?communicating the importance of fungi

– WP:POV. This is endorsing that viewpoint.birth complicacies

– birth complications.There are very few examples of museums entirely devoted to fungi (one example being the Museo del Hongo in Chile).

– the first and second parts pull in different directions, so to speak. This would need to be rephrased to not sound incongruent.relevant examples

– "relevant" is a MOS:Word to watch that should be used only with care. It's not outright inappropriate here, but it is redundant.Several relevant examples include:

– as noted several times above, avoid lists like these.fostering and supporting works able to stimulate dialogues

– very promotional.as for example from

– grammar.enhance the visibility of fungi

– promo-speak.The Fungi Foundation is the first non-governmental organisation dedicated to fungi

– being the first is something they would mention to promote themselves, but it is not something that is relevant for Wikipedia to mention here.signatories include Jane Goodall, Michael Pollan, Paul Stamets, Philipp Ball, Alan Rayner and many more

– "include" and "and many more" are redundant to each other. This also comes off basically the same way as the "Hello, I'm Tom Hanks. The US government has lost its credibility, so it's borrowing some of mine." joke from The Simpsons.and since 2023

– it's 2023 now, so I'd say it's way too early to say "since 2023" (at least in this context). It's basically making a promise about the future, which runs afoul of WP:CRYSTAL.The last report has been published in 2020.

– last or latest? It also was published.

Summary[edit]

GA review – see WP:WIAGA for criteria

- Is it well written?

- A. The prose is clear and concise, and the spelling and grammar are correct:

- See my comments above.

- B. It complies with the manual of style guidelines for lead sections, layout, words to watch, fiction, and list incorporation:

- See my comments above.

- A. The prose is clear and concise, and the spelling and grammar are correct:

- Is it verifiable with no original research?

- A. It contains a list of all references (sources of information), presented in accordance with the layout style guideline:

- B. All in-line citations are from reliable sources, including those for direct quotations, statistics, published opinion, counter-intuitive or controversial statements that are challenged or likely to be challenged, and contentious material relating to living persons—science-based articles should follow the scientific citation guidelines:

- See my comments above.

- C. It contains no original research:

- See my comments above.

- D. It contains no copyright violations nor plagiarism:

- Earwig reveals no overt copyvio. Because the article will need to be extensively rewritten before it can be promoted to WP:Good article status, I have not checked for WP:Close paraphrasing at this point.

- A. It contains a list of all references (sources of information), presented in accordance with the layout style guideline:

- Is it broad in its coverage?

- A. It addresses the main aspects of the topic:

- This is basically impossible to tell because it is unclear what the topic actually is. Like I said above, the article appears to lack a well-defined scope.

- B. It stays focused on the topic without going into unnecessary detail (see summary style):

- See my comments above.

- A. It addresses the main aspects of the topic:

- Is it neutral?

- It represents viewpoints fairly and without editorial bias, giving due weight to each:

- The article does not clearly distinguish between fact and opinion. See my comments above.

- It represents viewpoints fairly and without editorial bias, giving due weight to each:

- Is it stable?

- It does not change significantly from day to day because of an ongoing edit war or content dispute:

- It does not change significantly from day to day because of an ongoing edit war or content dispute:

- Is it illustrated, if possible, by images?

- A. Images are tagged with their copyright status, and valid non-free use rationales are provided for non-free content:

- See my comments above.

- B. Images are relevant to the topic, and have suitable captions:

- See my comments above.

- A. Images are tagged with their copyright status, and valid non-free use rationales are provided for non-free content:

- Overall:

- Pass or Fail:

- This is far from ready and qualifies for a WP:QUICKFAIL.

- Pass or Fail:

@CorradoNai: I'm closing this as unsuccessful. The list of issues above is not exhaustive, but a sample of issues I noted while reading through the article. I don't think this can be brought up to WP:Good article standards within a reasonable time frame.

I'll briefly summarize the main issues that keep this from being a WP:Good article in the foreseeable future:

- It is not clear what the scope of this article is (or is supposed to be). While it is possible to write articles with WP:BROAD scopes, the scope always needs to be well-defined. In other words, it should always be obvious what would be in scope and what would be out of scope. I would suggest looking at the sources on the overarching topic and see how they do it.

- The article is much longer than it needs to be. This is the result of uneconomical writing, mainly taking three forms (examples of all three are given above):

- Inclusion of irrelevant or loosely relevant material. Sometimes one or a few words or part of a sentence can be removed without losing any pertinent information. Sometimes a sentence or two can. Sometimes, it's an entire paragraph or section.

- Redundancy. This occurs on at least three different levels: (1) some information is needlessly repeated in several different sections, (2) some sentences overlap in content with other sentences in the same paragraph, and (3) some phrasings are outright tautological.

- Overly wordy phrasing. The numerous parenthetical glosses and the such contribute to this a lot. The somewhat flowery language is another contributing factor, as is a sometimes excessive use of descriptors, adjectives, and/or examples.

- The biggest issue that permeates the entire article is that it is not written like a Wikipedia article. Sources are often used to verify the underlying factual basis for the assertions made, rather than verifying the assertions themselves. This is a subtle form of WP:Original research, and is the reason that policy says that

References must be cited in context and on topic.

I would expect sources to be used in this way somewhere where original thought is allowed or even encouraged, perhaps an essay or a research paper. Beyond this, a lot of material lacks sources outright and the writing style/tone is often unencyclopedic—sometimes promotional, sometimes argumentative.

I'm afraid this means that my advice basically amounts to "start over and rewrite the entire article".

I gather that you are fairly new to this, and I don't want to discourage you from contributing to Wikipedia. To that end, I'll suggest WP:Peer review as a a more appropriate venue to bring this article to in order to get feedback and suggestions for improving the article (if you do that after addressing the core issues I noted above, you may ping me and I'll weigh in as time permits). You may also wish to consult the WP:Guild of Copy Editors. I would also suggest reading the essay WP:Writing better articles, as it covers a lot of issues that appear throughout this article. I will add some maintenance templates to the article. TompaDompa (talk) 16:32, 17 February 2023 (UTC)

Wonderful, thank you. I will address point by point. CorradoNai (talk) 18:07, 13 February 2023 (UTC)

GA Review - improving the page following reviewer comments[edit]

Dear TompaDompa (and everyone helping improving this page), many thanks for the very helpful comments, and in general for helping me become a better Wikipedian. I copy-pasted the comments below, and will answer point by point. I decided not to rewrite the page, because I hope that the structure of the page proves helpful as a framework to present very different examples of artworks within the same scope (how fungi directly and indirectly influence the arts). See also my answers to the general comments below. I hope that having a more precise scope of the article, shortening, and better incoporating sources might do the trick.CorradoNai (talk) 06:29, 23 February 2023 (UTC)

- @CorradoNai: I also noticed this article (it showed up in WP:Database reports/Pages containing too many maintenance templates due to the reviewer's extreme tagging). I'll try my best to get the article up to par, although it does need a lot of attention and I'm not sure I can make it alone. Please feel free to edit it also (if we don't have an edit conflict in the way). Duckmather (talk) 22:30, 12 March 2023 (UTC)

- Thanks a lot, Duckmather. It's a bit overwhelming but I was planning to tackle within the next weeks to, if not bring to GA level, at least remove the maintenance templates. Every help is very welcome. We can alway check with each other in case of major disagreements. Thanks! CorradoNai (talk) 06:15, 13 March 2023 (UTC)

General comments[edit]

- The article needs a lot of copyediting for spelling, grammar, tone, redundancies, and so on. I have noted several examples below.

- I will get through them. I'll also involve the WP:Peer review and the WP:Guild of Copy Editors as you suggested (I wasn't aware).CorradoNai (talk) 06:29, 23 February 2023 (UTC)

- Thanks, I will go through point by point. It seems like a lot, but also very helpful. Thanks for your work. — Preceding unsigned comment added by CorradoNai (talk • contribs) 10:33, 16 February 2023 (UTC)Reply

- The WP:Short description is

Use of fungal materials in artistic works

, which would seem to suggest that the article is about using fungi to create art (e.g. using fungus-based dyes for paintings) rather than depictions of fungi in art (e.g. paintings of fungi).- True. The short description is now changed to: Direct and indirect influence of fungi in the arts

- This article appears to lack a well-defined scope. Paintings of mushrooms, paintings made with fungus-based dyes, paintings made while under the influence of fungal psychedelics, and protecting paintings from mould are very different topics.

- Noted, thanks. Protection of artworks form fungal decay can go somewhere else (it's deleted from the page). The article wants to present very different artworks directly influenced by fungi, that is, all those artworks who would not exist without fungi. I hope that by following your comments and suggestions, the scope will be more clear. I also agree that this is a very broad scope for a Wikipedia page. I hope to narrow it down by having a well defined structure: that is, presenting how fungi are represented, symbolized, transformed, or utilized in the arts (see also my answer to your comment below). Again, this is very broad. So it is helpful to consider which fungal form influences which art form, which is overall how the page is structured. I could remove the indirect influence of fungi in the arts to help clarifying the scope. However, I think these are so prominent asnd prolific throughout history, that I believe they fit well within the scope of the page (that is, to present artworks that would not exist without fungi) CorradoNai (talk) 06:29, 23 February 2023 (UTC)

- The section headings don't follow MOS:HEADINGS. For instance, "Mushrooms in art" should just be "Mushrooms".

- Thanks, it is changed now.

- I see you were told on your talk page to not use date formatting like "2022-12-06" because people may be unsure whether "12" or "06" is the month. Ignore that. That's the ISO 8601 date format, which is internationally standardised, unambiguous, machine-readable, language-independent, and has some other benefits such as sorting chronologically when sorted numerically.

- Huge bummer, but noted. Thanks.

- The images from the 2022 Fungi Film Festival are tagged CC-BY-SA 4.0, which seems a bit odd to me. I was unable to verify this by following the link on the Commons page. I notice you uploaded both images. How did you make that determination?

- Those should be CC-BY 4.0 (maybe someone else changed attribution? not sure). I sought permission from the festival organisers to share with CC-By license, and they agreed.

- There are some MOS:CURLY quotation marks and apostrophes.

- Thanks, will change throughout the page.

- There are several hyphens that should be en dashes, see MOS:ENDASH.

- Ok, will change as I find them. — Preceding unsigned comment added by CorradoNai (talk • contribs) 09:02, 24 February 2023 (UTC)

- Where does the representation/showcase/transformation/utilization framework come from? It's referenced heavily throughout the article.

- That's an excellent point, and I was a bit worried that it is considered original research. The framework comes from me. I argue that it is a useful way to present how fungi influence the art, that is, the originality of it is nothing but a useful tool for an encyclopedic presentation of this topic. But correct, there is no reference for it. I hope it can remain in the page, but I will tone it down.

- It would be a lot easier to verify claims in the article if page numbers were always given for book citations.

- Noted, will do.

- There are a lot of repeated links. While it may sometimes be reasonable to repeat a link if the same thing is mentioned much later in the article, several of these are quite close to other identical links.

- Ok, will change. Thanks!

- The article needs careful copyediting for verb tense.

- Thanks, will do. I will try to involve the WP:Guild of Copy Editors as you suggested.

- Several (sub-)sections start with an excerpt or quote from a poem, song, or similar. This can sometimes be appropriate when used sparingly and judiciously, but it's overused here.

- Thanks, I will minimize the use of it and leave most illustrative examples.

Lead[edit]

== not addressed point by point, but rather as a whole - I believe other WIkipedians also already chipped in, so the lead is quite different from the original now == CorradoNai (talk) 13:52, 18 May 2023 (UTC)

- There's a lot of emphatic language here. Examples include

enormous influence

,extremely various and prolific

, andincredibly diverse

. This recurs in the body. - There is an overuse of parenthetical clarifications. This recurs in the body.

entheogenic (psychoactive)

– not synonyms. Either gloss entheogen properly or just say "psychoactive".Atzec

– typo.- The image caption is unsourced.

belonging to the eukaryotes (nucleated or 'higher' organisms)

– what's the relevance of this?being neglected or ignored

– this is an opinion expressed in WP:WikiVoice.Virtually all areas of the arts have been infiltrated by fungi

– overly poetic phrasing.Artists working with fungi are mostly representing (describing), showcasing (symbolizing), transforming, or utilizing them.

– the meaning of this is not obvious. I gather that this is rather important to the overall thesis (for lack of a better word) of the article.The distinction between these art practices and approaches are not clear-cut

– subject–verb disagreement.use them as narrative, rhetorical, stylistic, or stage element

– the last word should be plural.artists using fungi as transformative agent

– the last word should be plural.often explore the topic of transformation, decay, renewal, sustainability, circularity of matter

– is this one topic or several? Either way its ungrammatical.For 'indirect influence of fungi' it is meant the depiction or description of the effect of fungi

– grammar. Also WP:REFERSTO.the creation of art upon influence of fungi-derived substances

– "upon"?could also be considered an indirect influence of fungi in the art

– MOS:WEASEL.Further important aspects of fungi in art

– having the title appear in bold in the fourth paragraph of the lead is way too late. Either include it in the first paragraph (sentence, really) or not at all.

Fungi in art by artistic area[edit]

Traditionally, mushrooms have been the main subject for depiction in the arts [...] the enormous plasticity of fungi enables artists to work with different fungal forms to create very diverse artworks.

– unsourced.- In general, the issue I have is that the more introductory parts of the article (lead, and this one) are a wrap up of what is presented in the article itself. A source might well be not existant. When I say, for example, that "It is rare for artwork to depict several forms of fungi (such as across the fungus reproductive cycle), except in non-fiction literature, documentaries, or contemporary art" this is based on the many examples I could see and show in the article. I am not sure if this is original research or a way to present the examples of fungi in art

- It would seem to make more sense to have the image (technically images, plural) currently in this section in the lead and vice versa, since the former illustrates the topic's variety and the latter its history.

- this has been done by another Wikipedian (thank you!)

Artworks representing, showcasing, transforming, and utilizing fungi.

– which is which? The rest of the caption doesn't make that clear.- same as above

Clockwise from upper left

– I'm fairly certain that's not the case. Clockwise from upper left would end with the bottom left image, but the description seems to end with the bottom right one.- same as above

1000 BCE-500 AD

– use either BCE/CE or BC/AD, but be consistent. Since the rest of the article uses "BCE" consistently, I would suggest simply replacing "AD" with "CE" here. See also MOS:ENDASH.- will correct rhoughout the article

- The second paragraph consists of 7 sentences for a total of roughly 350 words. There is one source in the middle of the final sentence and five following the final clause. It is very unclear where the majority of the material in the paragraph comes from.

- I added a reference relative to fungiphobia, and just left 2 (in particular, the book by the Wassons will do - they were the first to introduce the notoin that the West thends towards mycophobia, the East towards mycophilia)

Mushrooms in art[edit]

- The first paragraph goes way WP:OFFTOPIC.

- It seems that a lot of this section has been edited already (thanks!). For points which have been already addressed, I will just say: "Already edited"

- What is the image of Baba Yaga doing here? The text in this section says nothing about Baba Yaga or Amanita muscaria.

- Down below is Baba Yaga a topic, so I left it for the time being. But noted.

Artists have often represented or described mushrooms as decorative, naturalistic, or symbolic element. In the graphic arts, architecture, sculpture, and literature, artists mostly represented or showcased mushrooms.

– not in the cited sources.- Already edited

mostly represented or showcased mushrooms

– as opposed to mostly doing something else with mushrooms or as opposed to mostly representing/showcasing something else?- As opposed to other fungal forms as mycelia, lichens, etc. However: Already edited

Currently, contemporary artists are increasingly

– MOS:CURRENT.- Already edited

Currently, contemporary artists are increasingly including mushrooms in their artworks.

– this statement is followed by three sources, two of which verify nothing while the third merely saysToday, according to the curator of a new art exhibition, artists are more interested in fungi than ever before.

The statement in this Wikipedia article is both stronger and more specific than the one made by the source.- Already edited

as for example in

– pleonasm.- Already edited

Early depictions of fungi are petroglyphs from the Bronze Age

– this is a general statement, but was presumably meant to be a specific one.- Already edited

Given the mysterious, seasonal, sudden, and at times inexplicable appearance of mushrooms, as well as the hallucinogenic or toxic effects of some species, their depiction in ethnic, classic and modern art (around 1860–1970) is often associated in Western art with the macabre, ambiguous, dangerous, mystic, obscene, disgusting, alien, or curious in paintings, illustrations, and works of fiction and literature.

– this kind of WP:ANALYSIS categorically needs to come from the sources.- I have given as source the book The Magic of Mushrooms by Sandra Lawrence, which covers these aspects

Visual artists representing mushrooms have been very prolific throughout history. Whereas examples before the 15th century are rare, examples abound from European visual arts from the 1500 onwards including periods as the Renaissance, the Baroque, Flemish, and Romantic periods.

– not in the cited source.- This comes from the NAMA registstry of fungi in art (https://namyco.org/art_registry.php), which I believe to be a reputable source. I have now refurmulated and I hope it's now Ok.

The 'Shaggy ink cap' and the Coprinus comatus

– these two are the same, right?- One is the common Enlgish name, the other the Latin one

The 'Shaggy ink cap' and the Coprinus comatus and the 'Common ink cap' Coprinus atramentaria mushrooms produce spores by deliquescing (liquefying, or melting) their cap into a black ink, which can be used in drawing, illustration, and calligraphy.

– this could and should be condensed. It contains a lot of unnecessary details.- Done

Protocols to produce the 'mushrooms ink' can be found online.

– WP:NOTHOWTO.- Already edited

as in petroglyphs representing mushroom-headed people discovered near the Pegtymel River (Siberia)

– already mentioned.- Already edited (I believe)

around the world, including in western and non-western works

– rather odd phrasing that doesn't provide much information. "Around the world" would seem to imply basically everywhere. Why elaborate further? Why use "western and non-western", specifically? Seems like WP:Systemic bias to me.- This comes from a transcluded page. I've not edited yet the original one.

more mushrooms are present in artworks from cultures considered to be mycophiles

– that hardly seems surprising. I might even expect this to be true by definition.- Already edited (I believe)

considered to be mycophiles

– by whom?- Already edited

- Does the entire first paragraph in the "Paintings, tapestries, and illustrations" subsection come from the source cited at the end?

- I have added the citation to the NAMA art registry. I took a lot of information from there.

collects and describe

– grammar.- Already edited

During the Victorian era, numerous scientists drew accurate illustrations of fungi, blurring the border between mycology and the arts.

– unsourced.- Already edited

- The Registry of Mushrooms in Works of Art is mentioned three separate times in different paragraphs.

- Already edited

Art periods and artists are categorized as follows in the registry:

– so what? This is clearly out of proportion in this article. It might belong in an article about the registry itself, but not here.- Already edited

Notable examples

– see MOS:Words to watch.- Already edited

Notable examples of visual artists depicting mushrooms and how they contributed to both mycology and the arts are:

– how were these examples chosen? This is also a bad use of a list in a prose article.- A bit randomly, I admit. I chose several examples which I thought would be varied enough, then transcluded from the respective Wikipedia pages

how they contributed to both mycology and the arts

– contributions to mycology are WP:OFFTOPIC if they don't relate to the arts. The Beatrix Potter entry is an example of going off-topic like this.- Already edited (I believe)

Hundreds of his paintings have been digitized by the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel (Philadelphia)

– superfluous detail.- Deleted

- The Charles Tulasne entry is entirely unsourced.

- I transcluded this

He is known for his excellent illustrations

– that's an opinion.- Same as above

174 13" by 15"

– clunky phrasing. This notation is also to be avoided, see MOS:INCH.- Same as above

- The Ernst Haeckel entry is entirely unsourced. It should also be "Haeckel" rather than "Häckel" per the linked article (the article on German-language Wikipedia likewise uses ae rather than ä, so this does not seem to be an Anglicization of the spelling).

- Same as above

A countless number [...] abound

– pleonasm.- Already edited (I believe)

Non-fiction books about fungi, especially those involving identification of fungi, includes photographs of fungal species and their fruiting bodies.

– subject–verb disagreement.- Already edited

Work of literary fiction

– grammar.- The mistake was 'work' instead of 'works'? If so, now fixed

Work of literary fiction involving mushrooms and fungi are often linked to [...]

– I'm guessing this is meant to say that the mushrooms and fungi, rather than the fiction itself, are linked to that stuff.- Both, to be honest. It's fungi inspiring the trope, so I am not sure I see the difference. Perhaps my formulation could have been better.

often linked to infection, decay, toxicity, mystery, fantasy, and ambiguity, and thus have mostly a negative connotation

– could you provide a quote from the source that verifies this?- I have reused the reference "The magic of Mushrooms" by Sandra Lwarence as it provides many examples

In line with the assumption

– whose assumption?- Specified (the Wassons')

During the Victorian era, fungi started to acquire a more playful, childish, or jolly role in works of literary fiction.

– not in the cited source.- Added source

Several renowned authors have used fungi as plot device.

– MOS:PUFFERY.- Already edited

These include Percy Shelly, Lord Alfred Tennyson, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, D.H. Lawrence, H.G. Wells, Ray Bradbury, and more.

– "These include" means that the list is non-exhaustive, making "and more" redundant. I also find it questionable that it's necessary to give this many examples.- I have removed two, if that helps

Lord Alfred Tennyson

– I've heard this person referred to as "Alfred, Lord Tennyson", "Lord Tennyson", "Alfred Tennyson", and often just plain "Tennyson", but never "Lord Alfred Tennyson". I don't know if it's strictly speaking incorrect, but it sticks out.- Removed

Percy Shelly

– typo.- Already edited

Fungi have been a common trope in the science fiction, horror, supernatural, fantasy and crime fiction genres. Fungi have a long tradition in science fiction.

– repetitive.- Already edited

In Ray Bradbury's Come into My Cellar

– the titles of short stories are presented in "quotation marks", not italics.- Already edited

alien invasors

– typo.Fungi have been a common trope in the science fiction, horror, supernatural, fantasy and crime fiction genres. [...] Crime and detective writer Agatha Christie has repeatedly used mushrooms as murder weapon in her crime fiction.

– does all of this come from the source cited at the end?- No, I added the source for Ray Bradbury's story

A non-exhaustive list of fictional stories involving mushrooms is given below:

– why? This is not TV Tropes.- Already edited

The quarterly periodical FUNGI Magazine runs a regular feature called Bookshelf Fungi reviewing fiction and non-fiction books on fungi.

– unsourced.- I added the external link at the end which I understad cannot be added in the main text. I am deleting the [source needed] comment but I am also reformulating the sentence in the hope this helps.

In Western culture poetry, as in literature, fungi are historically associated with negative feelings or sentiments, although, together with the rising popularity of fungi, this trend might hold less true in recent years.

– this kind of WP:ANALYSIS categorically needs to come from the sources.- I reformulated and made it more of a general statement which runs through the whole articles (references added before, e.g. the book by the Wassons)