Talk:Decipherment of rongorongo/De Laat

- A fully developed writing system

De Laat (2009) transliterates and translates in full the text of three tablets (E or Keiti, B or Aruku Kurenga and A or Tahua, respectively) and proposes that rongorongo is a predominantly syllabic writing system capable of accurately recording the Rapanui language.[1] Compared to Barthel and Pozdniakov, the accompanying syllabary substantially reduces the number of basic glyphs, in the first place because of the classification of a number of signs as being variants of the same glyph and secondly because a substantial number of signs are identified as fused glyphs, i.e., as composites of two or more basic glyphs. The signs representing the pure vowels are also used for the CV-combinations with consonants h and glottal stop.[note 1] The vowels can be long as well as short.

Basic syllabic grid according to De Laat[2] (h) ng k m n p r t v a

(h)a nga ka ma na pa ra ta va e

(h)e nge ke me ne pe re te ve i

(h)i ngi ki mi ni pi ri ti vi o

(h)o ngo ko mo no po ro to vo u

(h)u ngu ku mu nu pu ru tu vu

A small number of glyphs is believed to be of a disyllabic nature (VCV or CVV)[3] The failure to identify a number of glyphs such as ne and nu as syllables is partly explained by the fact that words such as nei ("here") and nui ("big") in which they occur most frequently have signs of their own.[4]

A special case is haka, which is formed from the ha-head and a torso with outstretched limbs. It is used to create causatives from verbs and verbs from adjectives or adverbs.[5] [note 2]

Disyllabic glyphs[3]

ina kai mai nei nui to(h)u vae haka

- Words

The majority of the syllabic and disyllabic glyphs are morphemes representing verbs, nouns, adverbs, adjectives or grammatical particles. The ma-sign for example may stand for the verb maa ("to know", "to examine", "to clean") or the benefactive particle ma ("for") and the ta-glyph for the noun ta ("mark"), the verb ta ("to strike"), the emphatic possessive particle ta ("possession of") or taha, "side" or "to evade".

Other words are created by fusing together two or more of these basic glyphs. Usually, these compounds are realized by simply pasting together two adjacent glyphs as in the case of hoki ("back", "again", "also"), taina ("brother", "sister"), tapu ("taboo"), tari ("to bring") and era ("there") or by putting them on top of each other: (h)au ("hat", "rope", "family", "scratch"), uha ("woman", "wife", "hen"), rangi ("to cry"), patu ("to lead away"), roro ("skull", "head", "mind"). Consequently, the prevailing reading order is from left to right and from top to bottom, although there are exceptions, especially in the more complex glyphs. Occasionally, one glyph is incorporated by another, as for example re by tu in ture ("grief", "rule"). The origins of the components involved sometimes get blurred to a certain degree as in raua ("they") and riva ("good").

Examples of fused glyphs[6]

ho-ki ta-ina ta-pu ta-ri e-ra (h)a-u u-ha ra-ngi pa-tu ro-ro tu-re ra-u-a ri-va

The fusion proces is greatly facilitated by the fact that basic glyphs can have different appearances, that they can be reduced in size or that only parts of them need to be used: e.g., the personal pronouns maatou (exclusive "we") and taatou (inclusive "we") are formed with partial ma- and ta-signs. In this last sign the ta-body is used, while tae ("not"), tutae ("filth", "to seduce") and mata ("axe", "spear", "eye", "face") are assembled with only the ta-birdhead. The ma-part in mate ("to die", "dead") differs slightly from that in maatou and mata.

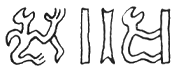

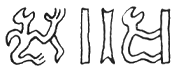

Syllable nga is represented by two apparently totally unrelated signs. The two nga-glyphs are the 'arrow-with-horns' which is easily appended to other glyphs (e.g. toenga ("rest")) and the 'headless body', which usually functions as carrier of other glyphs: for example in omnipresent composites as anga ("to do", "to work"), hanga ("to like", "to want") or tangata ("man"). This last figure also illustrates another of the script's features: the double use of the phonetic value of one of a composite's components, in this case that of ta. Other examples of this phenomenon are ika-i(ka) ("victims") and rongo-ro(ngo) ("to recite", "to believe").

Fusing of glyphs, however, is not obligatory in the writing of words: in apinga hauhaa ("valuable possessions"), for example, the initial glyph stands alone, and in poto-poto ("short") all the glyphs remain unconnected. The last example also illustrates that reduplicated forms can be written out in full as well.

Examples of fusions involving parts of glyphs and of component reduplication[6]

maa-tou taa-tou ta-e tu-ta-e ma-ta ma-te to-e-nga (h)a-nga ta-nga(-ta) i-ka-i(-ka) ro-ngo-ro(-ngo) a-pi-nga ha-u-ha-a po-to-po-to

According to De Laat, the fact that the phonetic value of a number of syllables is clearly derived from the name of the represented object - for example ta from taha ("frigate bird"), ka from ika ("fish"), ma from mango ("shark"), ina from mahina ("moon") and tu from hetuu ("star")[3] - gives support to Guy's idea[7] that the peculiar verses of the so-called procreation chant Atua Matariri are in fact a spelling bee overheard and misinterpreted by the illiterate informant Ure Va'e Iko. De Laat suggests that the names that were used by the pupils to enumerate the syllabic components in such an exercise were ''the names of the objects these had originally been derived from":[8]

Such an exercise, for example, could have been: "Mango ki ai ki roto Taha ka pu Mata", which to the untrained ear would have sounded like "Shark by merging with Frigate bird produces the Obsidian axe", but to the initiated simply meant "ma combined with ta gives mata."

— De Laat 2009:212

The remark of Eyraud that "each figure has its own name"[9] seems to confirm such a scenario:

It is (...) something he would never have written had he simply been given the signs' syllabic values. Unfortunately, it lead him (and many others after him) to believe that rongorongo was a form of pictographic - and hence primitive - writing.

— De Laat 2009:212

- Texts

The following excerpts from the analysis of the text of tablet E or Keiti.[10] illustrate the principles at work in the formation of sentences out of words. This text - like that of the other two tablets that were analysed - appears to contain spoken words only:

The texts of tablets E, B and A consist exclusively of dialogue. The same probably holds true for the tablets that are related to A (H, P and Q) and E (C, G and K). The texts can be divided into segments consisting of one or more sentences, which can be attributed to different speakers.

— De Laat 2009:78

In all three the subject of the (lengthy) discussions is a disturbing event which happens or has happened as the text begins. In the text of tablet E this is the murder of a woman. A man called Taea - presumably her husband - is accused by members of the victim's family of having killed his wife with his stone axe. In the beginning the man denies that his weapon is involved until this is firmly established. He then argues that it must have been used by someone else and he ridicules his accusers' inability to find conclusive evidence against him:

Excerpts from lines Er6-Er8[11]

e he tanga(ta) riva o mata e tae anga ki ko uha mo haaki na ariki e ta(ta)ri mea era (Taea:) (I) (am) an honest man regarding this axe, then (I) did not use (it) against that woman! If (you) inform the chief, (he) will be expecting something!

too na ina o mata e tae haaki kee ki anga tohu hauu e tae anga tapa na hakari na (He) will accept nothing regarding this axe, then (it) would not present different information when a slave was the evildoer! And surely (her) body is not going to give an account?

This temporarily confuses the accusers until one of them suggests that the use of a sharp weapon and the resistance of the victim will probably have left some marks on the body of the attacker. At this point, they begin to understand that their suspect has covered himself with elaborate bodypaintings to hide the evidence of his crime:

Excerpts from lines Ev1-Ev7[12]

to-a to vie tanga(ta) ira mahaki iti vie maa ta ta o-ka - o-ka taea (Accusers:) That man there (is) the murderer of (his) wife! (That) woman (was) a dear relative! (We) will investigate signs of stabbing, Taea!

au ha-hau to-a taea mata ite ko a-pi taea rero-re(ro) haii mo renga na rero-re(ro) ko naa ta vae The scratches will fasten the murderer, Taea! The face (we) see has been covered, Taea! Are those smears enveloping (you) because (it's) beautiful (or) are those smears hiding the marks (on your) legs?

maa haka-ki[te] ra koro ngaaha huha he huha haauraa huha tae ite raua maa i au ii no kona - kona ha-ha Cleaning (them) will reveal if (your) limbs are torn! These unseen limbs (are) meaningful limbs: they (are) the evidence! These scratches here simply fill (every) bodypart (we) touch!

- Further observations and speculations

The fact that there appears to be only dialogue brings De Laat to speculate upon the function of the examined tablet texts as belonging or being related to some form of dramatical performance.[13] Furthermore, the author points at the "supplementary layers of meaning" that are present in some parts of the texts. Sometimes, these make use of the pictographical dimension of the glyphs - much in the same way as is done in other hieroglyphic systems. An example of this is the writing of prefix tae ("not") which often turns its 'head' away from the word it precedes as if to visibly underline the negation (cf. the excerpts of lines Er6-8).[14] [note 3] Others appear to be connected with certain numbers: the beginning of tablet A for instance, contains sequences of ten tu-, ten rae/era- and ten (h)u-glyphs (3 x 10 = 30). Barthel (1962) has noted that among the Easter Islanders existed a group of clearly preferred numbers, namely three, six, ten and thirty.[15] De Laat speculates that the lunar calender detected by Barthel on tablet C or Mamari could very well be such a layer of meaning supplementary to the primary text.[14] As features such as these have clearly been directed at a reader, the question is presented whether these rongorongo texts were exclusively meant to be read aloud to an audience.[16]

- Notes

- ^ For this reason and because the sources deal with it in a confusing way, De Laat does not transliterate the glottal stop (De Laat 2009: 6).

- ^ Only one other usage was found: hakari ("body") (De Laat 2009:50).

- ^ Apparently, this reversed writing of tae is also applied in tutae to express the objectionability of the concept (cf. tutae) (De Laat 2009: 217).

- References

- ^ De Laat 2009:5

- ^ De Laat 2009:7

- ^ a b c De Laat 2009:8

- ^ De Laat 2009:47-48

- ^ De Laat 2009:49

- ^ a b De Laat 2009:9ff

- ^ Guy 1999b

- ^ De Laat 2009:212

- ^ Eyraud 1886:71

- ^ De Laat 2009:83-108

- ^ De Laat 2009:91-93

- ^ De Laat 2009:97-107

- ^ De Laat 2009:213-215

- ^ a b De Laat 2009:217

- ^ Barthel 1962:5

- ^ De Laat 2009:218-219

- Bibliography

- de Laat, M. (2009). Words out of wood, proposals for the decipherment of the Easter Island script. Delft: Eburon Academic Publishers. ISBN 9789059722835.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Barthel, Thomas S. (1962). "Zählweise und Zahlenglaube der Osterinsulaner". Abhandlungen und Berichte des Staatlichen Museums für Völkerkunde. 21: 1–22.

{{cite journal}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) (in German) - Churchill, William (1912). Easter Island, the Rapanui Speech and the Peopling of Southeast Polynesia. Washington.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Eyraud, Eugène (1886). Annales de la Propagation de la Foi (Annals of the Propagation of the Faith). pp. 36: 52–71, 124–138. Lyon.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) (in French) - Du Feu, Veronica (1996). Rapanui. London: Routledge.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Fuentes, Jordi (1960). Diccionario y gramática de la lengua de la Isla de Pascua Pascuense-Castellano Castellano-Pascuense Dictionary & Grammar of the Easter Island Language Pascuense-English English-Pascuense. Santiago.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)