Talk:2020 Atlantic hurricane season/Link Archiver/3

Hurricane Marco[edit]

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 20 – August 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 991 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began to track a tropical wave located over the central Tropical Atlantic at 00:00 UTC on August 16.[1] Initially hindered by its speed and unfavorable conditions in the eastern Caribbean, the wave began organizing once it reached the central Caribbean on August 19.[2] At 15:00 UTC on August 20, the NHC designated the wave as Tropical Depression Fourteen.[3] Intensification was initially slow, but the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Marco at 03:00 UTC on August 22, becoming the earliest 13th named Atlantic storm, beating the previous record of 2005's Hurricane Maria and 2011's Tropical Storm Lee by 11 days.[nb 1][4] Marco passed just offshore of Honduras and, as a result of favorable atmospheric conditions, quickly intensified to an initial peak of 65 mph (105 km/h) and a pressure of 992 mb, with a characteristic eye beginning to form on radar.[5] After a Hurricane Hunters flight found evidence of sustained winds above hurricane force, Marco was upgraded to a Category 1 hurricane at 11:30 a.m. CDT on August 23, making it the third hurricane of the season.[6] Despite this, northeasterly vertical wind shear created by a trough situated northwest of Marco displaced its convection, exposing its low-level center, which caused the system to begin weakening significantly early on August 24.[7][8] At 23:00 UTC, Marco made landfall near the mouth of the Mississippi River as a weak tropical storm with winds at 40 mph (64 km/h) and a pressure of 1006 mb.[9] Marco degenerated into a remnant low just south of Louisiana at 09:00 UTC on August 25.[10]

Contrary to prior predictions, Marco's track was shifted significantly eastward late on August 22, as the system moved north-northeastward instead of north-northwestward, introducing the possibility of successive landfalls around Louisiana from both Laura and Marco.[11][5][12] However, Marco ultimately weakened faster than anticipated, and its landfall in Louisiana was much less damaging than initially feared, only causing around $35 million in damage. The storm indirectly killed 1 person in Chiapas, Mexico.[13]

Tropical Storm Omar[edit]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 31 – September 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1003 mbar (hPa) |

In the last few days of August, a cold front spawned a trough over Northern Florida and eventually a low-pressure area formed offshore of the southeast coast of the United States. The low rapidly organized as it drifted on top of the Gulf Stream, and was classified as Tropical Depression Fifteen at 21:00 UTC on August 31.[14] Moving generally northeastward away from North Carolina, the depression struggled to intensify in a marginally favorable environment with warm Gulf Stream waters being offset by high wind shear.[15] Eventually, satellite estimates revealed that the depression was intensifying and the system became consolidated enough to be upgraded to a tropical storm and as a result was given the name Omar at 21:00 UTC on September 1.[16] This event marked the earliest formation of the fifteenth named storm on record in the North Atlantic, exceeding the record of Hurricane Ophelia in 2005 by six days.[16] After maintaining its intensity for 24 hours, northwesterly wind shear of 50 knots weakened the storm back to a tropical depression.[17][18] Although wind shear continued to plague the system, Omar managed to remain a tropical cyclone.[19] Early on September 4, Omar fell to 30 mph amid the wind shear, and despite repeated forecasts for Omar to weaken further into a remnant low, Omar re-strengthened back to 35 mph 12 hours later.[20][21] Early on September 5, Omar made a jog to the north; however, the center began to fully separate from the bursts of convection, and at 21:00 UTC that day, Omar degenerated into a remnant low.[22][23] The low moved northeastward, reaching Scotland on September 9.

While still a depression moving away from the United States, the storm brought life-threatening rip currents and swells to the coast of the Carolinas.[24]

Hurricane Nana[edit]

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 1 – September 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 994 mbar (hPa) |

On August 27, the NHC began to monitor a tropical wave that was moving westward over the Atlantic.[25] The wave moved into the southern Caribbean, where conditions were more favorable for development. Although it was not yet clear as to whether or not there was a well-defined low-level circulation (LLC), the system managed to achieve gale-force winds and because it was an imminent threat to land, the NHC initiated advisories on Potential Tropical Cyclone Sixteen at 15:00 UTC on September 1.[26] A hurricane hunter aircraft closed circulation was found, and the system was upgraded to Tropical Storm Nana an hour later, making it the earliest 14th named Atlantic storm on record, surpassing Hurricane Nate of 2005 by four days.[27][28] By 03:00 UTC the following day, the storm strengthened some more, obtaining 1-minute sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h).[29] Afterward, moderate northerly shear of 15 knots halted the trend and partially exposed the center of circulation.[30] The central pressure of Nana fluctuated between 996 and 1000 mbars (29.41 and 29.53 inHg) throughout the day on September 2, while sustained winds remained steady at 60 mph.[30] Early the next day, a slight center reformation and a burst of convection allowed Nana to quickly intensify into a hurricane at 03:00 UTC on September 3. Simultaneously, it reached its peak intensity with 1-minute sustained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 994 mbars (29.36 inHg).[31] Three hours later, Nana made landfall between Dangriga and Placencia in Belize near peak intensity.[32] Nana then began to rapidly weaken, dropping below hurricane status three hours after it made landfall,[33] and weakening to a tropical depression at 21:00 UTC.[34] Nana's low-level center then dissipated and the NHC issued their final advisory on the storm at 03:00 UTC on September 4.[35] The mid-level remnants eventually spawned Tropical Storm Julio in the eastern Pacific on September 5.[36][37]

Nana was the first hurricane to make landfall in Belize since Hurricane Earl in 2016.[38] The storm caused street flooding in the Bay Islands of Honduras.[39] Hundreds of acres of banana and plantation crops were destroyed in Belize, where a peak wind speed of 61 mph (98 km/h) was reported at a weather station in Carrie Bow Cay.[40] Total economic losses in Belize exceeded $20 million. Heavy amounts of precipitation also occurred in northern Guatemala.[41]

Hurricane Paulette[edit]

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 7 – September 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 965 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began to track a tropical wave located over Africa on August 30.[42] The wave organized and formed an area of low pressure on September 6, but convective activity remained disorganized.[43][44] In the early hours of September 7, it became more organized, and the NHC began issuing advisories for Tropical Depression Seventeen at 03:00 UTC on September 7.[45] Before becoming a tropical depression, the storm had previously struggled to organize due to short-lasting convective bursts with little consistency.[46] At 15:00 UTC on September 7, the NHC upgraded the system to Tropical Storm Paulette, the earliest 16th named Atlantic storm, breaking the previous record set by 2005's Hurricane Philippe by 10 days.[47][48] It moved generally west-northwestward over the warm Atlantic waters and it gradually intensified. At 15:00 UTC on September 8, Paulette reached its first peak intensity with 1-minute sustained winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) with a minimum central pressure of 995 mbar (29.39 inHg).[49] It held that intensity for 12 hours before an increase in wind shear weakened the storm.[50][51] On September 11, despite an estimated 40 knots (45 mph) of deep-layer southwesterly shear and dry air entrainment, Paulette began to re-intensify.[52] The shear began to relax after that, allowing Paulette to become more organized and begin to form an eye.[53] At 03:00 UTC on September 13, Paulette was upgraded to hurricane status.[54] Dry air entrainment gave the storm a somewhat ragged appearance, but it continued to slowly strengthen as it approached Bermuda with its eye clearing out and its convection becoming more symmetric.[55] Paulette then made a sharp turn to the north and made landfall in northeastern Bermuda at 09:00 UTC on September 14 with 90 mph (150 km/h) winds and a 973 mb (28.74 inHg) pressure.[56] The storm then strengthened into a Category 2 hurricane as it accelerated northeast away from the island.[57] It reached its peak intensity at 18:00 UTC that day, with winds of 105 mph (170 km/h) and a pressure of 965 mb (28.50 inHg).[58] It was originally forecasted to become a major hurricane as it accelerated northeast, but increasing wind shear and dry air entrainment caused the storm's intensity to remain unchanged for the next day.[59] On the evening of September 15, it began to weaken and undergo extratropical transition,[60] which it completed the next day.[61]

After about five days of slow southward movement, the extratropical cyclone began to redevelop a warm core and its wind field shrank considerably. By September 22, it had redeveloped tropical characteristics and the NHC resumed issuing advisories shortly thereafter.[62] Between Paulette's initial formation and its reformation, seven other tropical or subtropical storms had formed in the Atlantic. It moved eastward over the next day, and became post-tropical for the second time in its lifespan early on September 23[63] and subsequently dissipated.

Trees and power lines were downed all over Bermuda, leading to an island-wide power outage.[64] Despite warnings of high rip current risk by the National Weather Service, a 60-year-old man drowned while swimming in Lavallette, New Jersey after being caught in rough surf produced by Hurricane Paulette.[65]

Tropical Storm Rene[edit]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 7 – September 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

On September 6, a tropical wave emerged off the coast of Africa and subsequently began to rapidly organize. At 09:00 UTC on September 7, it was upgraded to Tropical Depression Eighteen roughly halfway between Africa and Cabo Verde.[66] The depression strengthened just east of Cabo Verde, becoming Tropical Storm Rene just twelve hours later.[67] Rene became the earliest 17th named Atlantic storm, breaking the previous record set by Hurricane Rita in 2005 by 11 days.[68] Three hours later, Rene made landfall on Boa Vista Island with 1-minute sustained winds of 40 mph (65 km/h) and a pressure of 1001 mbars (29.56 inHg).[69] Although the storm lost some organization while moving through the Cabo Verde Islands, it remained a minimal tropical storm before it weakened to a tropical depression at 03:00 UTC on September 9.[70][71] The system re-strengthened to a tropical storm twelve hours later while continuing to fight easterly wind shear.[72] It strengthened further, and attained its peak intensity with 1-minute sustained winds of 50 mph and a minimum central pressure of 1000 mbars (29.53 inHg) at 15:00 UTC on September 10.[73] However, the continued effects of dry air and some easterly wind shear weakened the storm again, and eventually caused it to be downgraded to a tropical depression at 15:00 UTC on September 12.[74][75] Bursts of deep convection allowed it to maintain tropical depression status for two more days before it began to rapidly unravel on September 14[76] and degenerated into a remnant low at 21:00 UTC the same day.[77] The low continued to move generally westward over the next two days before opening up into a surface trough at 17:30 UTC on September 16.[78][79][80][81]

A tropical storm warning was issued for the Cabo Verde Islands when advisory were first issued on the storm at 09:00 UTC on September 7.[66] Rene produced gusty winds and heavy rains across the islands, but no serious damage was reported.[82] The warning was discontinued at 21:00 UTC on September 8.[83]

Hurricane Sally[edit]

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 11 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 965 mbar (hPa) |

On September 10, the NHC began to monitor an area of disturbed weather over The Bahamas for possible development.[84] Over the next day, convection rapidly increased, became better organized, and formed a broad area of low-pressure on September 11.[85] At 21:00 UTC, the system had organized enough to be designated as Tropical Depression Nineteen.[86] At 06:00 UTC on September 12, the depression made landfall just south of Miami, Florida, with winds of 35 mph (55 km/h) and a pressure of 1007 mbar (29.74 inHg).[87] Shortly after moving into the Gulf of Mexico, the system strengthened into Tropical Storm Sally at 18:00 UTC the same day[88] and became the earliest 18th named Atlantic storm, surpassing the previous record set by Hurricane Stan in 2005 by 20 days.[89] Northwesterly shear caused by an upper-level low caused the system to have a sheared appearance, but it continued to strengthen as it gradually moved north-northwestward.[90] Sally began to go through a period of rapid intensification around midday on September 14. Its center reformed under a large burst of deep convection and it strengthened from a 65 mph (105 km/h) tropical storm to a 90 mph (140 km/h) Category 1 hurricane in just one and a half hours.[91][92] It continued to gain strength and became a Category 2 hurricane later that evening.[93] However, upwelling due to its slow movement as well increasing wind shear weakened Sally back down to Category 1 strength early the next day.[94] It continued to steadily weaken as it moved slowly northwest then north, although its pressure continued to fall.[95] However, as Sally approached the coast, its eye quickly became better defined and it abruptly began to re-intensify.[96] By 05:00 UTC on September 15, it had become a Category 2 hurricane again.[97] At around 09:45 UTC, the system made landfall at peak intensity near Gulf Shores, Alabama with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) and a pressure of 965 mbars (28.50 inHg).[98][99] The storm rapidly weakened as it moved slowly inland, weakening to a Category 1 hurricane at 13:00 UTC[100] and to a tropical storm at 18:00 UTC.[101] It further weakened to a tropical depression at 03:00 UTC on September 17[102] before degenerating into a remnant low at 15:00 UTC.[103]

A tropical storm watch was issued for the Miami metropolitan area when the storm first formed, while numerous watches and warnings were issued as Sally approached the U.S. Gulf Coast. Several coastline counties and parishes on the Gulf Coast were evacuated. In South Florida, heavy rain led to localized flash flooding while the rest of peninsula saw continuous shower and thunderstorm activity due to asymmetric structure of Sally. The storm made landfall on Gulf Shores, Alabama on the 16 year anniversary of Hurricane Ivan making landfall on the same location in 2004. The area between Mobile, Alabama and Pensacola, Florida took the brunt of the storm with widespread wind damage, storm surge flooding, and over 20 inches (51 cm) of rainfall which peaked at 30 inches at NAS Pensacola. Several tornadoes touched down as well.[104] Eight people were killed and damage estimates were at least $5 billion.[105]

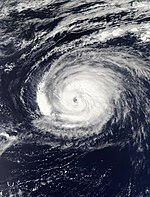

Hurricane Teddy[edit]

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 12 – September 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min); 945 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began to monitor a tropical wave over Africa at 00:00 UTC on September 7.[106] The wave entered the Atlantic Ocean on September 10, and began to organize.[107] At 21:00 UTC on September 12, the NHC designated the disturbance as Tropical Depression Twenty.[108] It struggled to organize for over a day due to its large size and moderate wind shear.[109] After the shear decreased, the system became better organized and strengthened into Tropical Storm Teddy at 09:00 UTC on September 14, making it the earliest 19th Atlantic tropical / subtropical storm on record, beating the unnamed 2005 Azores subtropical storm by 20 days.[110][111] It continued to intensify as it became better organized, with an eye beginning to form late on September 15.[112] It then rapidly intensified into a hurricane around 06:00 UTC the next day.[113] The storm continued to intensify, becoming a Category 2 hurricane later that day.[114] However, some slight westerly wind shear briefly halted intensification and briefly weakened the storm to a Category 1 at 03:00 UTC on September 17.[115] When the shear relaxed, the storm rapidly re-intensified into the second major hurricane of the season at 15:00 UTC that day.[116] Teddy further strengthened into a Category 4 hurricane six hours later, reaching its peak intensity of 140 mph (220 km/h) and a pressure of 945 mb (27.91 inHg).[117] Internal fluctuation and an eyewall replacement cycle caused the storm to weaken slightly to a Category 3 hurricane at 09:00 UTC on September 18.[118] Soon after, Teddy briefly re-strengthened into a Category 4 hurricane before another eyewall replacement cycle weakened it again.[119][120] Continued internal fluctuations caused the eye to nearly dissipate and Teddy weakened below major hurricane status at 12:00 UTC on September 20.[121]

Teddy continued moving north, weakening to a Category 1 hurricane as it began to merge with a trough late on September 21. [122] A Hurricane Hunters flight found that Teddy had strengthened a bit, due to a combination of baroclinic energy infusion from the trough and warm oceanic waters from the Gulf Stream and it was upgraded back to Category 2 status.[123] Teddy also doubled in size as a result of merging with the trough. The hurricane kept expanding and started an extratropical transition while it neared Nova Scotia's south coast; although Teddy appeared to be a post-tropical cyclone, Hurricane Hunters also found a warm core in Teddy's center.[124] However, it weakened back to a Category 1 hurricane before transitioning to a post-tropical cyclone at 00:00 UTC on September 23.[125] Post-Tropical Cyclone Teddy made landfall near Ecum Secum, Nova Scotia approximately 12 hours later with maximum sustained winds near 65 mph (100 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 964 mbar (28.47 inches).[125] It then moved rapidly north-northeastward across the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to the west of Newfoundland as a decaying extratropical low.[126]

On September 18, a man and a woman drowned in the waters off La Pocita Beach in Loíza, Puerto Rico due to the rip currents and churning waves that Teddy caused in the north of the Lesser and Greater Antilles.[127][128] Another person drowned due to rip currents in New Jersey.[129]

Tropical Storm Vicky[edit]

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 14 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

In the early hours of September 11, a tropical wave moved off the coast of West Africa.[130] The disturbance steadily organized, and the NHC issued a special advisory to designate the system as Tropical Depression Twenty-One at 10:00 UTC on September 14.[131] The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Vicky five hours later based on scatterometer data, becoming the earliest 20th tropical / subtropical storm on record in an Atlantic hurricane season, surpassing the old mark of October 5, which was previously set by Tropical Storm Tammy in 2005.[132][133] It was also the first V-named Atlantic storm since 2005's Hurricane Vince.[134] Despite extremely strong shear removing all but a small convective cluster to the northeast of its center, Vicky intensified further, reaching its peak intensity with 1-minute sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) and a pressure of 1000 mbar (29.53 inHg) at 03:00 UTC on September 15.[135][136] Eventually, 50 knots (60 mph) of wind shear began to take its toll on Vicky, and Vicky's winds began to fall.[137] It weakened into a tropical depression at 15:00 UTC on September 17 before degenerating into a remnant low six hours later.[138][139] The low continued westward producing weak disorganized convection before opening up into a trough late on September 19 and dissipating the next day.[140][141][142]

The tropical wave that spawned Tropical Storm Vicky produced flooding in the Cabo Verde Islands less than a week after Tropical Storm Rene moved through the region. One person was killed in Praia on September 12 from the tropical wave.[143][144]

- ^ Stacy Stewart (August 16, 2020). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Andrew Latto (August 19, 2020). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Robbie Berg (August 20, 2020). "Tropical Depression Fourteen Public Advisory Number 1". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Kimberly Miller, Doyle Rice (August 21, 2020). "Two Gulf hurricanes at the same time? Tropical Storm Laura has formed". usatoday.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Robbie Berg (August 22, 2020). "Tropical Storm Marco Discussion Number 10". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2020.

- ^ Andrew Latto (August 23, 2020). "Hurricane Marco Tropical Cyclone Update". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ Andrew Latto (August 23, 2020). "Hurricane Marco Discussion Number 14". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ David Zelinsky (August 24, 2020). "Hurricane Marco Discussion Number 15". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ David Zelinsky (August 24, 2020). "Tropical Storm Marco Tropical Cyclone Update". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (August 25, 2020). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Marco Public Advisory Number 21". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ "Hurricane MARCO Advisory Archive". nhc.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Jonathan Erdman (August 22, 2020). "Tropical Storms Laura and Marco Could Deliver Back-to-Back Landfalls on U.S. Gulf Coast; Here's How Rare That Is". weather.com. The Weather Company. Archived from the original on August 22, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2020.

- ^ Fredy Martín Pérez (August 23, 2020). "Muere niña en Chiapas por afectaciones de la tormenta tropical "Marco"". El Universal. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ Eric Blake (August 31, 2020). "Tropical Depression Fifteen Public Advisory Number 1". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ Andrew Latto (August 31, 2020). "Tropical Depression Fifteen Discussion Number 2". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Eric Blake (September 1, 2020). "Tropical Storm Omar Discussion Number 5". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ Robbie Berg (September 2, 2020). "Tropical Depression Omar Discussion Number 7". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ Dave Roberts (September 2, 2020). "Tropical Depression Omar Public Advisory Number 9". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ "Tropical Storm OMAR Advisory Archive". nhc.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 4 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Andrew Latto (September 4, 2020). "Tropical Depression Omar Discussion Number 14". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ David Zelinsky (September 4, 2020). "Tropical Depression Omar Discussion Number 16". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ John Cangialosi (September 5, 2020). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Omar Discussion Number 21". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ John Cangialosi (September 5, 2020). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Omar Public Advisory Number 21". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ "Tropical Depression Fifteen forms just off shore". WMBF News. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ Andrew Latto (August 27, 2020). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ Andrew Latto (September 1, 2020). "Potential Tropical Cyclone Sixteen Public Advisory Number 1". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ Eric Blake; Stacy Stewart (September 1, 2020). Tropical Storm Nana Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ Cappucci, Matthew (September 1, 2020). "Tropical storm Nana nears formation in Caribbean as Atlantic hurricane season stays unusually active". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Dan Brown (September 2, 2020). "Tropical Storm Nana Public Advisory Number 4". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ a b "Tropical Storm Nana Advisory Archive". nhc.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 3 September 2020. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ Dan Brown (September 3, 2020). "Hurricane Nana Discussion Number 8". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 4, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ Richard Pasch (September 3, 2020). "Hurricane Nana Intermediate Advisory Number 8A". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ Richard Pasch (September 3, 2020). "Tropical Storm Nana Public Advisory Number 9". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ Jack Beven (September 3, 2020). "Tropical Depression Nana Public Advisory Number 11". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ Dan Brown (September 4, 2020). "Remnants of Nana Discussion Number 12". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ David Zelinsky (September 5, 2020). "Tropical Storm Julio Discussion Number 1". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ "Tropical Storm JULIO Advisory Archive". nhc.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Sosnowski, Alex (September 2, 2020). "Nana strikes Belize as hurricane with damaging winds, flooding rainfall". AccuWeather. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ Travis Fedschun, Janice Dean. "Hurricane Nana makes landfall in Belize, brings floods to Honduras;Omar to dissipate". Fox News. Archived from the original on 2020-09-14. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ Staff (September 3, 2020). "Farms in southern Belize lose hundreds of acres to Hurricane Nana". Breaking Belize News. Archived from the original on September 6, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "Nana hits Belize, then dissipates over Guatemala". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2020-09-04. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (August 30, 2020). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ John Cangialosi (September 6, 2020). "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ John Cangialosi (September 6, 2020). "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (September 7, 2020). "Tropical Depression Seventeen Public Advisory Number 1". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (September 7, 2020). "Tropical Depression Seventeen Discussion Number 1". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ David Zelinsky (September 7, 2020). "Tropical Storm Paulette Discussion Number 3". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Erdman, Jonathan (September 7, 2020). "Tropical Storm Paulette, Record Earliest 16th Storm, Forms in Eastern Atlantic While Tropical Storm Rene is Soon to Follow". weather.com. The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on September 7, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ David Zelinsky (September 8, 2020). "Tropical Storm Paulette Public Advisory Number 7". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ David Zelinsky (September 8, 2020). "Tropical Storm Paulette Public Advisory Number 8". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ Eric Blake (September 9, 2020). "Tropical Storm Paulette Public Advisory Number 9". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ Andrew Latto (September 11, 2020). "Tropical Storm Paulette Forecast Advisory Number 21". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Robbie Berg (September 12, 2020). "Tropical Storm Paulette Discussion Number 24". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ David Zelinsky (September 13, 2020). "Hurricane Paulette Public Advisory Number 25". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Andrew Latto (September 13, 2020). "Hurricane Paulette Discussion Number 28". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (September 14, 2020). "Hurricane Paulette Public Advisory Number 30". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Dave Roberts (September 14, 2020). "Hurricane Paulette Tropical Cyclone Update". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Dave Roberts (September 14, 2020). "Hurricane Paulette Intermediate Advisory Number 31A". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ David Zelinsky (September 15, 2020). "Hurricane Paulette Discussion Number 33". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Dave Roberts (September 15, 2020). "Hurricane Paulette Public Advisory Number 36". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Dave Roberts (September 16, 2020). "Hurricane Paulette Public Advisory Number 39". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Daniel Brown (September 21, 2020). "Tropical Storm Paulette Forecast/Advisory #40". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Brian Dunbar (September 23, 2020). "NASA's Terra Satellite Confirms Paulette's Second Post-Tropical Transition". Hurricane And Typhoon Updates. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ "Knocked down tress and power lines: Damage reported as Hurricane 'Paulette' makes rare landfall in Bermuda". Deccan Herald. September 15, 2020. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ^ "Man drowns at New Jersey shore in seas churned by hurricane". WPVI. September 15, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Dan Brown (September 7, 2020). "Tropical Depression Eighteen Public Advisory Number 1". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ John Cangialosi (September 7, 2020). "Tropical Storm Rene Public Advisory Number 3". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ John Cangialosi (September 7, 2020). "Tropical Storm Rene Discussion Number 3". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (September 7, 2020). "Tropical Storm Rene Intermediate Advisory Number 3A". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ John Cangialosi (September 8, 2020). "Tropical Storm Rene Discussion Number 6". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- ^ Jack Beven (September 9, 2020). "Tropical Depression Rene Public Advisory Number 9". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ Richard Pasch (September 9, 2020). "Tropical Storm Rene Public Advisory Number 10". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ Richard Pasch (September 10, 2020). "Tropical Storm Rene Public Advisory Number 14". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Dan Brown (September 11, 2020). "Tropical Storm Rene Discussion Number 16". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Andrew Latto (September 12, 2020). "Tropical Depression Rene Public Advisory Number 22". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Dan Brown (September 14, 2020). "Tropical Depression Rene Discussion Number 30". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ David Zelinsky (September 14, 2020). "Remnants of Rene Public Advisory Number 31". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Andrew Hagen. "Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Maria Torres, Nelsie Ramos. "Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Amanda Reinhart. "Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Mike Formosa. "Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ Sewell, Katie (8 September 2020). "Tropical Storm Rene path: Rene blasts Cabo Verde Islands as NHC forecast hurricane upgrade". Express.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ John Cangialosi (September 8, 2020). "Tropical Storm Rene Public Advisory Number 7". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Eric Blake (September 9, 2020). "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Robbie Berg (September 11, 2020). "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Eric Blake (September 11, 2020). "Tropical Depression Nineteen Public Advisory Number 1". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Jack Beven (September 12, 2020). "Tropical Depression Nineteen Intermediate Advisory Number 2A". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Richard Pasch (September 12, 2020). "Tropical Storm Sally Intermediate Advisory Number 4A". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Niles, Nancy; Hauck, Grace; Aretakis, Rachel (September 12, 2020). "Tropical Storm Sally forms as it crosses South Florida; likely to strengthen into hurricane when it reaches Gulf". USA Today Network. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Dan Brown (September 13, 2020). "Tropical Storm Sally Discussion Number 8". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Dan Brown (September 14, 2020). "Tropical Storm Sally Discussion Number 12". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Dan Brown (September 14, 2020). "Hurricane Sally Discussion Number 13". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Dan Brown (September 14, 2020). "Hurricane Sally Discussion Number 14". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (September 15, 2020). "Hurricane Sally Intermediate Advisory Number 15A". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Dan Brown (September 15, 2020). "Hurricane Sally Discussion Number 17". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Robbie Berg (September 16, 2020). "Hurricane Sally Tropical Cyclone Update". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (September 16, 2020). "Hurricane Sally Tropical Cyclone Update". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Jay Reeves; Angie Wang; Jeff Martin (2020-09-16). "Hurricane Sally blasts ashore in Alabama with punishing rain". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 2020-09-17. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ Stacy Stewart, Eric Blake (September 16, 2020). "Hurricane Sally Tropical Cyclone Update". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Dan Brown (September 16, 2020). "Hurricane Sally Tropical Cyclone Update". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Dan Brown (September 16, 2020). "Tropical Storm Sally Intermediate Advisory Number 22A". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Richard Pasch (September 17, 2020). "Tropical Depression Sally Public Advisory Number 24". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Greg Carbin (September 17, 2020). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Sally Public Advisory Number 26". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ "Hurricane Sally Crawling Toward Gulf Coast With Potentially Historic and Life-Threatening Flooding". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on 2020-09-15. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

AonSeptemberwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Stacy Stewart (September 7, 2020). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Robbie Berg (September 10, 2020). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Andrew Latto (September 12, 2020). "Tropical Depression Twenty Public Advisory Number 1". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Andrew Latto (September 12, 2020). "Tropical Depression Twenty Discussion Number 1". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (September 14, 2020). "Tropical Storm Teddy Discussion Number 7". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Marchante, Michelle; Harris, Harris (September 14, 2020). "With newly formed Tropical Storm Teddy, NHC tracking five named systems at once". The Miami Herald. Archived from the original on September 14, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ David Zelinsky (September 15, 2020). "Tropical Storm Teddy Discussion Number 13". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Eric Blake (September 16, 2020). "Hurricane Teddy Tropical Cyclone Update". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Eric Blake (September 16, 2020). "Hurricane Teddy Public Advisory Number 16". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Robbie Berg (September 16, 2020). "Hurricane Teddy Discussion Number 19". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Andrew Latto (September 17, 2020). "Hurricane Teddy Public Advisory Number 21". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Andrew Latto (September 17, 2020). "Hurricane Teddy Public Advisory Number 22". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ John Cangialosi (September 18, 2020). "Hurricane Teddy Discussion Number 24". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ Richard Pasch (September 19, 2020). "Hurricane Teddy Public Advisory Number 27". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ David Zelinsky (September 19, 2020). "Hurricane Teddy Discussion Number 28". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Eric Blake (September 20, 2020). "Hurricane Teddy Intermediate Advisory Number 32A". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Eric Blake (September 21, 2020). "Hurricane Teddy Discussion Number 38". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ Dave Roberts (September 22, 2020). "Hurricane Teddy Discussion Number 39". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ Eric Blake (September 22, 2020). "Hurricane Teddy Discussion Number 41". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ a b Eric Blake (September 23, 2020). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Teddy Intermediate Advisory Number 42A". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ^ Eric Blake (September 23, 2020). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Teddy Discussion Number 46". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ^ "Dos personas mueren ahogadas en Piñones". Primera Hora. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ "Los bañistas que visiten las playas del norte este fin de semana: "Podrían poner en riesgo sus vidas"". El Nuevo Día. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ Chris Sheldon (September 25, 2020). "Swimmer dies after being pulled from ocean off Jersey Shore beach". nj.com. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ Robbie Berg (September 11, 2020). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Stacy Stewart, Jack Beven (September 14, 2020). "Tropical Depression Twenty-One Special Advisory Number 1". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Michals, Chris (September 14, 2020). "Sally takes aim at the Gulf Coast; only one name left for hurricane season". wsls.com. Roanoke, Virginia: WSLS-TV. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Dave Roberts (September 14, 2020). "Tropical Storm Vicky Public Advisory Number 2". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Alvarez-Wertz, Jane (September 14, 2020). "Tropical Storm Vicky becomes 20th named storm of the 2020 season, 5 named storms currently in Atlantic". wavy.com. Portsmouth, Virginia: WAVY-TV. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Richard Pasch (September 15, 2020). "Tropical Storm Vicky Discussion Number 4". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 2020-09-16. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Richard Pasch (September 15, 2020). "Tropical Storm Vicky Public Advisory Number 4". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 2020-09-16. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Michael Brennan (September 16, 2020). "Tropical Storm Vicky Discussion Number 10". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Dan Brown (September 16, 2020). "Tropical Storm Vicky Public Advisory Number 14". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Dan Brown (September 16, 2020). "Tropical Storm Vicky Public Advisory Number 15". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ "Tropical Weather Discussion". NHC. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "Tropical Analysis" (PDF). NHC. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "Tropical Analysis" (PDF). NHC. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "Cape Verde – Deadly Flash Floods in Praia". floodlist.com. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Hurricane Sally expected to bring historic flooding to Mississippi, Alabama, Florida Panhandle » Yale Climate Connections". Yale Climate Connections. 15 September 2020. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

Cite error: There are <ref group=nb> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=nb}} template (see the help page).