Saint-André d'Évol Church

| Saint-André d'Évol Church | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Parish church |

| Architectural style | Romanesque art |

| Address | Within the Évol hamlet |

| Town or city | Olette commune, Pyrénées-Orientales department, Occitania region. |

| Country | France |

| Coordinates | 42°34′14″N 2°15′14″E / 42.57056°N 2.25389°E |

| Closed | Church, Parish church (until 1603) |

| Owner | Municipality of the Olette commune |

| Awards and prizes | Monument historique (1943) |

| Designations | Adscribed to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Perpignan-Elne jurisdiction from the Catholic Church confession |

The Saint-André d'Évol Church (Catalan: Sant Andreu d'Èvol) is a Romanesque Catholic church in the hamlet of Évol, in the commune of Olette, in the French department of Pyrénées-Orientales within the Occitania region.

Built in the 11th century, Saint-André church underwent an extension in the 18th century. Starting in 1577, it became the headquarters of a rosary company, which remained active for several centuries, keeping the place active despite the loss of its parish church status in the early 17th century. The entire building was listed as a historic monument in 1943.

Its Latin cross plan comprises a nave extended on the east by a semicircular apse, a large rosary chapel on the north and a bell tower on the south. The apse and bell tower are decorated with Lombard arcatures. The interior of the apse is original for its two semicircular absidioles recessed into the walls, and the exterior for the width of the lesenes separating the arcatures.

A conjuratory, placed in front of the church, was used by the priest to ward off bad luck and in particular strong storms, frequent in the region, attributed to the numerous witches believed to live in the upper valley of the ribera d'Èvol, located upstream.

The church is home to altarpieces, tabernacles, statues, paintings, and silverware (chalices, beakers, crosses). Many of these objects, dating from the 13th to 18th centuries, have been classified as historic monuments since the 20th century.

Location[edit]

In the eastern Pyrenees, the watersheds of the ribera d'Èvol and ribera de Cabrils form the Garrotxes, a poor and depopulated region.[1] The small village of Évol lies on the banks of the river of the same name, at around 750 m altitude. The church of Saint-André lies to the north of the village, which is administratively part of the French department of Pyrénées-Orientales and the commune of Olette.

Évol and its church of Saint-André can be reached via a departmental road about three kilometers long, from Route Nationale 116, which links the Roussillon plain to the Cerdagne region, slightly upstream from the village of Olette. Railleu and Ayguatébia-Talau, further west, can also be reached via a mountain road that follows the course of the ribera de Cabrils. The nearby village of Oreilla can be reached on foot via a signposted path.

-

View of Évol, with Saint-André church.

-

Typical houses in Évol.

-

The church seen from the south.

-

The church seen from the north.

-

Staircase leading to the church.

Built on a steep slope in the Évol cemetery, Saint-André church can be reached from the village by a long flight of steps.

History[edit]

Saint-André church was built at the beginning of the 11th century according to the traditional plan of Romanesque churches in the region: a single nave oriented west-east, extended to the east by a semicircular apse,[2] all accessible through a door in the southern wall of the nave.[3] A square bell tower was added to the nave, near the apse on the south side, probably in the last quarter of this century.[4]

The first mention of the church dates from 1347,[2] when a merchant from Villefranche-de-Conflent bequeathed it five sous.[3]

A rosary company was created at Saint-André d'Évol in 1577. To mark the occasion, a large altarpiece was installed[5] and the church was enlarged to include a rosary chapel.[6] By the 16th century, the village of Olette had become more populous and wealthier than Évol, but was not yet entitled to parish status. In 1559, the parish priest of Évol asked his bishop for permission to baptize newborns in the churches of Oreilla and Olette, but the inhabitants of Olette found this request insufficient and accused the parish priest of incapacity. He was acquitted in 1568.[7] Sainte-Marie d'Olette was first mentioned as a parish church in 1597.[8] In 1603, Saint-André d'Évol lost its parish status to the church of Sainte-Marie d'Olette (renamed Saint-André),[9] becoming its suffragan.[2][10]

In the 18th century, the top of the bell tower was remodeled. This may have been a restoration after the bell tower had been damaged.[4] The rosary chapel was enlarged in 1723 and blessed on April 7, 1724.[3][6] A new sacristy was built in 1751[8] to replace the old one, which, was nestled in a wall of the bell tower, and blessed as Christ's chapel in 1727.[6] In 1772, the renovation of the Rosary Company was formalized, and the terms and conditions of the company's worship were defined.[11]

During the Ancien Régime, the church's curate owned a large house below the place of worship, which served as the clergy house, as well as outbuildings for agricultural use, the land surrounding the cemetery and two irrigated fields.[12] In 1791, these lands -with the exception of the rectory garden- were sold for a very small sum, less than the estimate for major repairs to the clergy house dated 1781. The outbuildings were occupied by a family without authorization.[13] Also in 1791, the municipal council of the new commune of Évol met in the clergy house kitchen. On this occasion, the door connecting this room to the rest of the building was bricked up.[14] By 1827, the commune of Évol had become part of Olette, but the clergy house kitchen continued to be used as a meeting room by the villagers, while the rest of the building remained occupied by priests.[15]

| External image | |

|---|---|

From 1938 to 1945, the parish priest for Olette, Évol and Les Garrotxes was Jacques Llopet. Under his leadership, the building was listed as a historic monument in 1943.[16][17] The remains of the conjuratory on the church steps were restored in 1950.[14] In the 1960s, Abbé Llopet published two monographs on the Garrotxes region, in which the church of Saint-André figured prominently.[18]

In the course of the 20th and 21st centuries, several objects in the church were listed as historic monuments.

As of 2009, the municipality of Olette decided to purchase the former clergy house.[19] A fundraising campaign was launched in 2015, with the help of the Fondation du Patrimoine, to restore the building.[20] The work planned includes securing the surroundings, treating the facades and openings, and re-roofing with slate.[21]

Architecture[edit]

-

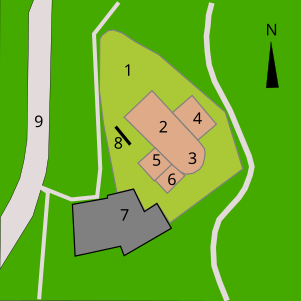

Site map: 1. Cemetery; 2. Nave; 3. Apse; 4. Rosary chapel; 5. Bell tower; 6. Sacristy; 7. Old presbytery; 8. Conjuraor; 9. Road.

Saint-André church is a Romanesque building with a single nave (interior dimensions: 20 m long by 6 m wide)[22] following an east–west axis, extended to the east by a semicircular apse. The door is located in the south wall. In addition to this typically Romanesque layout, a rectangular belfry tower is built on the south side of the church, close to the apse. In the corner formed by the apse and bell tower is a sacristy. The plan of the church is in the shape of a cross, the southern arm of the cross being formed by the bell tower, opposite which a large square chapel, known as the Rosary Chapel, forms the northern arm.[3]

-

Southeast view with, from left to right, the bell tower, sacristy, apse and rosary chapel.

-

The apse with its arcatures and skylights.

-

West view: cemetery and back of nave.

The apsefeatures two semi-circular apses recessed into the walls on the interior side.[2] This archaizing feature, similar to that found in some 10th-century churches, is perhaps an allusion to the Trinity.[3] The exterior is decorated with Lombard arcatures and lesenes,[2] as is usual in early Romanesque churches, but here again with an original feature: the exceptional width of the lesenes.[3]

Bell tower[edit]

The bell tower is square, 6.50 m square, and 15 m high. It has three floors.[23]

The first floor is a small, rectangular, unlit room, 3 m high, which connects the bell tower to the nave of the church. The second floor, also rectangular and 5 m high, has a double-arched window in the middle of the south wall. The second floor is square-shaped, 4 m high and features three large pointed-arch windows, which have now been bricked up. The third floor has a bay on each side, except for the north face. The varying interior dimensions of the floors are explained by the different thicknesses of the walls.[23]

The tower is covered by a roof sloping towards the west, the north wall being extended upwards by a bell tower with two bays similar to those on the third floor. The two corners of the south wall are each topped by a rectangular gable surmounted by a pyramid.[23]

-

The bell tower

-

Top of the bell tower.

The conjuratory[edit]

In front of the church are the remains of a conjuratory, consisting of two stone arcades.[14]

Conjuratorys are small buildings open at the four cardinal points, which enabled the parish priest to ward off bad luck and witches, reputedly numerous in Évol and the upper valley of the ribera d'Èvol. In particular, with the help of the tocsin from the nearby bell tower, it was able to ward off heavy rainfall, frequent in the region (Mediterranean episodes, thunderstorms), and attributed to the forces of Evil.[24][25] According to journalist and explorer Gabrielle Maud Vassal, "everyone" in the valley believed in these legends and spells back in 1934.[26]

-

Conjuratory in front of the church.

-

Conjuratory and bell tower.

The presbytery[edit]

Below the church is a large square house with an upper floor and attic: the presbytery. According to Jacques Llopet, it dates from the 10th or 11th century.[12] For the Fondation du Patrimoine, it's more likely to be an 18th-century building.[21] The house contains a square room with a separate entrance, measuring around 5 m on each side: this is the former kitchen, reused after the French Revolution as a meeting room by the villagers, where municipal councils met when Évol was a commune.[27] An old, walled-in door connected this room to the rest of the presbytery.[28] It was also in this room that the Évol commune archives were kept.[29]

Furnishings[edit]

The sanctuary preserves an important church treasure, many elements of which are protected as historic monuments, testifying to the continuation of a lively cult over the centuries.[3]

Tabernacle and silverware[edit]

These include a tabernacle with painted wooden panels depicting the Virgin Mary, St. John, and a chalice topped with a communion host, dated 1553 and listed on May 11, 2001.[30]

The church also houses several pieces of silverware:

- A late 17th-century goldsmith's cross-reliquary with a 19th-century foot (height: 46 cm, 29 cm without base, length: 22 cm, listed as a historic monument on June 27, 2005).[31]

- A 17th-century silver chalice, known as the "Rosary chalice", without paten, in repoussé, chased and engraved silver, probably made in conjuratory. The base features an engraving of the Virgin and Child of the Rosary. It bears the donor's name on the base. The whole measures 25 cm. The diameter of the bowl is 9.5 cm and 15.4 cm at the base. Classified on May 16, 2003.[32]

- Another chalice, with its paten, in gilded, embossed, and engraved silver. This chalice is decorated with floral motifs and measures 24.5 cm high. Its diameter is 9 cm at the bowl and 14.4 cm at the base. The paten is in the shape of a circular plate, 15 cm in diameter. The set, probably made in Perpignan, dates from the 17th century and has been listed as a historic monument since May 16, 2003.[33]

- A silver repoussé Rosary beaker. It takes the form of a truncated cone, 7.5 cm high, 9 cm in diameter at the opening, and 6 cm at the base. The beaker has two handles, giving it a width of 14 cm. It is decorated with a Virgin and Child on one side and a saint on the opposite. The base bears the mark of master silversmith Jean Albar, as well as that of the city of Perpignan, and the letter R to indicate the date (1772-1773). It was made in 1772 and classified as a historic monument on May 16, 2003.[34]

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Statue of a Virgin and her cadireta[edit]

| Madonna | |

|---|---|

| Year | 13th century |

| Medium | Pine wood |

| Dimensions | 71.5 cm × 14.5 cm × 31 cm (28.1 in × 5.7 in × 12 in) |

| Designation | Object classified as a historical monument (1971) |

The church features a Romanesque statue of the Virgin and Child, 71.5 cm high, 31 cm wide, and 14.5 cm high.[11] Carved from a pine log, it shows the Virgin Mary seated. The Virgin's face shows the original polychromy, while her clothes have been repainted. The Virgin's feet have been cut off and the Infant Jesus is missing.[35] It is presented in a cadireta, i.e. a processional canopy, consisting of a rectangular support and four wooden columns supporting a dome decorated with a baluster gallery. The whole is painted and gilded and measures 134 cm high, 48 cm wide, and 44 cm deep.[36]

| Cadireta | |

|---|---|

| Year | 17th century |

| Medium | Wood |

| Dimensions | 134 cm × 44 cm × 48 cm (53 in × 17 in × 19 in) |

| Designation | Object classified as a historical monument (2001) |

The statue dates from the last quarter of the 13th century,[11] and the cadireta from the 17th century.[36]

A document from 1772 stipulates that members of the Rosary brotherhood had to take the statue out in procession every first Sunday of the month to obtain indulgences. The procession consisted of going around the cemetery, receiving an absolution for their deceased confreres. The procession then returned to the church, and the statue was placed on the altar of the Rosary chapel, where mass was celebrated.[11]

The Virgin and Child was listed as a historic monument on April 7, 1971,[11] and its canopy on May 11, 2001.[36] The statue was restored in 2005.[11]

The Miracle of Notre-Dame d'Évol[edit]

| The Miracle de Notre-Dame d’Évol | |

|---|---|

| Year | 1647 |

| Medium | Canvas |

| Subject | Oil painting |

| Designation | Object classified as a historical monument (2001) |

The Miracle of Notre-Dame d'Évol is a painting (oil on canvas) depicting an overturned boat in a stormy sea. In the boat are several figures, one of whom is praying. One has fallen into the water. In the upper left-hand corner appears the Virgin Mary holding the Infant Jesus in her arms.[37]

This is an ex-voto. In the lower left-hand corner is a dedication explaining the motivation for the painting: in January 1647, a priest, Jean-François Pujol d'Olette, on a sea voyage from Rome to Marseille, almost drowned in a storm. After the priest began praying to Our Lady of the Rosary of Evol, the storm immediately ceased.[37]

Painted before 1650, it was listed as a historic monument on May 11, 2001.[37]

Altarpiece of Saint John the Baptist[edit]

| Altarpiece of Saint John the Baptist | |

|---|---|

| Year | 15th century |

| Medium | Wood |

| Dimensions | 250 cm × 215 cm (98 in × 85 in) |

| Designation | Object classified as a historical monument (1953) |

Since the 20th century, Saint-André church has housed a Gothic altarpiece dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, complete with its predella.[38]

The altarpiece is 250 cm high and 215 cm wide. The altarpiece consists of a central panel (height 200 cm, width 80 cm) and two lateral panels (height 183 cm, width 65 cm), surmounted by a 49 cm high predella. Each of the four panels is made of painted, carved, and gilded wood.[38]

The side panels each feature three paintings on the life of John the Baptist. Left: the vision of Zechariah (father of John the Baptist), the visitation of the Virgin Mary, and the birth of Saint John the Baptist. Right: St. John announcing the coming of Christ, the beheading of St. John, and the presentation of his head at Herod's banquet, followed by his burial. The central panel features two scenes: the baptism of Christ by St. John, and St. John with a praying Viscount d'Evol at his feet.[38]

The predella shows five scenes from the Passion of Christ: Judas' betrayal, Jesus before Pilate, the crucifixion, the descent from the cross, and Christ's burial, alternating with four coats of arms:[38] those of the De So family, Viscounts of Evol, present twice, and two others that are derived from them: those of Aragall and those of Çà Garriga associated with their de So husbands. These coats of arms allow us to date the painting: Blanche d'Aragall may refer either to Bernat de So's wife and mother of Guillem de So (Viscount of Evol from 1413 to 1428), or to the latter's cousin and wife. Éléonore de Çà Garriga was Guillem de So's second wife. The altarpiece was therefore created towards the end of Guillem de So's life, between 1423 and 1428, and it is he who is depicted praying.[39]

-

Coat of arms of Évol and the de So family.

-

Coat of arms of Blanche d'Aragall.

-

Coat of arms of Éléonore de Çà Garriga.

This work is attributed to the Master of Roussillon and dates from the first half of the 15th century. It was originally intended for the chapel of Saint-Jean-Baptiste de La Bastida, located in the lower part of Olette. Around 1800, it was moved to the chapel of Saint-Étienne d'Évol, a hundred meters north of Saint-André. The predella and two panels were stolen, then recovered in New York in the 1930s, before being installed in Saint-André church. The altarpiece and predella were classified as historic monuments on February 18, 1953.[38]

Rosary altarpiece[edit]

| Rosary altarpiece | |

|---|---|

| Year | 1578 |

| Medium | Wood |

| Dimensions | 350 cm × 295 cm (140 in × 116 in) |

| Designation | Object classified as a historical monument (2001) |

This altarpiece, 3.50 m high and 2.95 m wide, is made up of painted panels surrounding a sculpture of the Virgin Mary placed in a niche at its center.[5]

The panels are composed of fifteen paintings representing the fifteen traditional mysteries of the Rosary.[5] These mysteries are divided into three categories: the "joyful mysteries" (the Annunciation, the Visitation, the Nativity, the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, the Finding in the Temple); the "sorrowful mysteries" (the Agony of Jesus, the Flagellation, the Coronation of Thorns, the Carrying of the Cross, the Crucifixion); finally, the "glorious mysteries" (the Resurrection of Jesus, the Ascension, Pentecost, the Assumption, the Coronation of Mary).

Commissioned by the Evol rosary brotherhood when it was created in 1577, it was completed in 1578, repainted and varnished in the 19th century, and classified as a historic monument on May 11, 2001.[5]

Altarpiece of Saint Andrew[edit]

| Altarpiece of Saint Andrew | |

|---|---|

| Year | 1680 |

| Medium | Wood |

| Dimensions | 400 cm × 590 cm (160 in × 230 in) |

| Designation | Object classified as a historical monument (2001) |

An altarpiece known as the "Saint André" altarpiece is located in the church apse. Measuring 4 m high and 5.90 m wide, it is a triptych comprising a central section and two side panels, with a total of five statues, three bas-reliefs, and a painting on canvas. Each element is framed by gilded twisted columns.[40]

The five statues, all placed in niches, represent respectively Saint Andrew, flanked by Saint John the Baptist and Saint Michael (in the central section), the Virgin and Child, and Saint Joseph (each in one of the side panels). At the top of the altarpiece there is a painted canvas showing the Crucifixion.[40]

This work is dated 1680 and 1786, with the date 1786 written in a cartouche. It was repainted in the 19th century, probably with additional cabinetwork, and placed in the apse at the same time. It was listed as a historic monument on May 11, 2001, and restored in 2012.[40]

Holy Thursday Tabernacle[edit]

| Holy Thursday Tabernacle | |

|---|---|

| Year | 18th century |

| Medium | Wood and glass |

| Dimensions | 80 cm × 33.5 cm × 45.5 cm (31 in × 13.2 in × 17.9 in) |

| Designation | Object listed as a historical monument (2015) Object classified as a historical monument (2016) |

The Holy Thursday tabernacle is a rectangular lantern-shaped object, glazed on the top and three sides, made of painted, gilded and carved pinales. It measures 80 cm high, 45.5 cm wide and 33.5 cm deep. The unglazed back is painted dark blue and gilded. It is fitted with four round, gilded feet, and decorated at the corners with moldings and stylized leaves.[41]

It was used to present the chalice and communion host during Holy Week Masses.[41]

The object dates from the 18th century. It was listed as a historic monument on May 19, 2015, then classified on December 12, 2016.[41]

Other objects[edit]

Jacques Llopet mentions an 18th-century statue of the Virgin and Child in Saint-André church. In his opinion, this statue, created by a local craftsman, is of no artistic interest: the details are exaggerated, the colors are too bright and the proportions of the body are not respected, with hands that are too large. The statue, some thirty centimeters high, was exhibited in Perpignan in 1946. In 1968, Jacques Llopet noted that it had disappeared.[42]

The Chapel of Christ houses a seventeenth-century statuette of Christ on the Cross.[42]

References[edit]

- ^ (ca) "Les Garrotxes de Conflent" archive, Gran Enciclopèdia Catalana, on enciclopedia.cat, Barcelone, Editions 62.

- ^ a b c d e Mallet 2003, p. 227, 228.

- ^ a b c d e f g Catalunya romànica.

- ^ a b Bailbé 1989, p. 55.

- ^ a b c d (fr) "Retable du Rosaire, 15 tableaux : les Quinze mystères du Rosaire, statue : Vierge à l'Enfant", Palissy database.

- ^ a b c Llopet 1961, p. 44.

- ^ Llopet 1961, p. 18, 19.

- ^ a b Llopet 1961, p. 20.

- ^ (ca) Pere Ponsich, "Sant Andreu, abans Santa Maria, d’Oleta", on Catalunya romànica, t. VII : La Cerdanya. El Conflent, Barcelone, Fundació Enciclopèdia Catalana, 1995

- ^ (ca) Mercè Subirats i Pla et Ramon Corts i Blay, Diccionari d'història eclesiàstica de Catalunya, vol. 2 : D-O, Generalitat de Catalunya, 1998, p. 132.

- ^ a b c d e f (fr) "Statue: Vierge assise", Palissy database.

- ^ a b Llopet 1961, p. 59.

- ^ Llopet 1961, p. 60.

- ^ a b c (fr) "Église Saint-André d'Évol (XIème siècle)" archive, on evol66.fr.

- ^ Llopet 1961, p. 62, 63.

- ^ Llopet 1968, p. 9.

- ^ (fr) "Église Saint-André d'Evol", Mérimée database.

- ^ Llopet 1961 and Llopet 1968.

- ^ (fr) Olette-Évol town council, "Séance du 27 août 2014" archive.

- ^ (fr) Olette-Évol town council, "Séance du 17 septembre 2015" archive.

- ^ a b (fr) "Ancien presbytère d'Évol" archive, on fondation-patrimoine.org, Fondation du Patrimoine.

- ^ Llopet 1961, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Bailbé 1989, p. 52.

- ^ Abélanet 2008, p. 105.

- ^ (fr) "Évol", on Les plus beaux villages de France, Flammarion, 2018.

- ^ Vassal 1934, p. 366.

- ^ Llopet 1961, p. 60-62.

- ^ Llopet 1961, p. 62.

- ^ Llopet 1961, p. 63.

- ^ (fr) "Tabernacle", Palissy database.

- ^ (fr) "Croix-reliquaire", Palissy database.

- ^ (fr) "Calice du Rosaire", Palissy database.

- ^ (fr) "Calice et patène", Palissy database.

- ^ (fr) "Gobelet de quête du Rosaire", Palissy database.

- ^ Mathon, Dalmau et Rogé-Bonneau 2013, p. 348.

- ^ a b c (fr) "Dais de procession dit cadireta", Palissy database.

- ^ a b c (fr) "Ex-voto: Le Miracle de Notre-Dame d'Évol", Palissy database.

- ^ a b c d e (fr) "Retable de saint Jean-Baptiste, 3 tableaux, prédelle", Palissy database.

- ^ Llopet 1968, p. 30.

- ^ a b c (fr) "Retable de saint André, 5 statues, 3 bas-reliefs, tableau", Palissy database.

- ^ a b c (fr) "Tabernacle du Jeudi saint", Palissy database.

- ^ a b Llopet 1968, p. 78.

See also[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

Books and articles[edit]

- (fr) Jean Abélanet, Lieux et légendes du Roussillon et des Pyrénées catalanes, Canet, Trabucaire, coll. "Mémoires de pierres, souvenirs d'hommes", 2008, 189 p. ISBN 978-2-84974-079-8

- (fr) Aymat Catafau, "Le rôle de l'église dans la structuration de l'habitat sur le versant français des Pyrénées : L'exemple du Conflent", in Villages pyrénéens : Morphogénèse d'un habitat de montagne, Toulouse, Presses universitaires du Midi, 2001 (ISBN 978-2-8107-0993-9, read online archive)

- (fr) Marcel Durliat, in Dictionnaire des églises de France, Robert Laffont, Paris, 1966, tome II-C, Cévennes-Languedoc-Roussillon, p. 112

- (fr) Noël Bailbé, Les clochers-tours du Roussillon, Perpignan, Société agricole, scientifique et littéraire des Pyrénées-Orientales, 1989 (ISSN 0767-368X)

- (fr) Jacques Llopet, Olette, Evol, les Garrotxes, Perpignan, impr. catalane, 1961

- (fr) Jacques Llopet, Histoire et art religieux dans les Garrotxes, Bar-le-Duc, imp. Saint-Paul, 1968

- (fr) Jean-Bernard Mathon (dir.), Guillaume Dalmau and Catherine Rogé-Bonneau, Corpus des Vierges à l'Enfant (xiie - xve siècle) des Pyrénées-Orientales, Presses universitaires de Perpignan, coll. "Histoire de l'art", 2013 (ISBN 978-2-35412-185-3, read online archive)

- (fr) Géraldine Mallet, Églises romanes oubliées du Roussillon, Montpellier, Les Presses du Languedoc, 2003, 334 p. ISBN 978-2-85998-244-7

- (fr) Under the direction of Jean-Marie Pérouse de Montclos, Le guide du patrimoine Languedoc Roussillon, Hachette, Paris, 1996, p. 241, ISBN 978-2-01-242333-6

- (ca) "Sant Andreu d'Évol", in Catalunya romànica, t. VII: La Cerdanya. El Conflent, Barcelona, Fundació Enciclopèdia Catalana, 1995 (read online archive)

- (fr) Gabrielle Vassal, "En Roussillon : Le château d'Évol et les étangs de Nohèdes", La Revue du Touring-club de France, November 1934 (read online archive)

Ministry of Culture files[edit]

- (fr) "Église Saint-André d'Evol" archive, on the open heritage platform, Mérimée database, French Ministry of Culture

- (fr) "Dossier de protection, Église Saint-André d'Evol" archive [PDF], Mérimée database, French Ministry of Culture

- (fr) "Retable de saint Jean-Baptiste, 3 tableaux, prédelle" archive, on the open heritage platform, Palissy database, French Ministry of Culture

- (fr) "Statue : Vierge assise" archive, on the open heritage platform, Palissy database, French Ministry of Culture

- (fr) "Ex-voto: le Miracle de Notre-Dame d'Evol" archive, on the open heritage platform, Palissy database, French Ministry of Culture

- (fr) "Dais de procession dit cadireta" archive, on the open heritage platform, Palissy database, French Ministry of Culture

- (fr) "Retable du Rosaire, 15 tableaux : les Quinze mystères du Rosaire, statue : Vierge à l'Enfant" archive, on the open heritage platform, Palissy database, French Ministry of Culture

- (fr) "Tabernacle" archive, on the open heritage platform, Palissy database, French Ministry of Culture

- (fr) "Retable de saint André, 5 statues, 3 bas-reliefs, tableau" archive, on the open heritage platform, Palissy database, French Ministry of Culture

- (fr) "Calice du Rosaire" archive, on the open heritage platform, Palissy database, French Ministry of Culture

- (fr) "Chalice et patène" archive, on the open heritage platform, Palissy database, French Ministry of Culture

- (fr) "Gobelet de quête du Rosaire" archive, on the open heritage platform, Palissy database, French Ministry of Culture

- (fr) "Croix-reliquaire" archive, on the open heritage platform, Palissy database, French Ministry of Culture

- (fr) "Tabernacle du Jeudi saint" archive, on the open heritage platform, Palissy database, French Ministry of Culture