People of the Red Orchestra

This is a list of participants, associates and helpers of, and certain infiltrators (such as Heinz Pannwitz) into, the Red Orchestra (German: Die Rote Kapelle) as it was known in Germany. Red Orchestra was the name given by the Abwehr to members of the German resistance to Nazism and anti-Nazi resistance movements in Allied or occupied countries during World War II. Many of the people on this list were arrested by the Abwehr or Gestapo. They were tried at the Nazi Imperial War Court before being executed either by hanging or guillotine, unless otherwise indicated. As the SS-Sonderkommando also took action against Soviet espionage networks within Switzerland, people who worked there are also included here.[1]

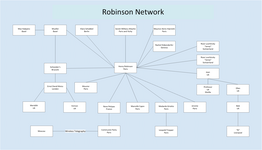

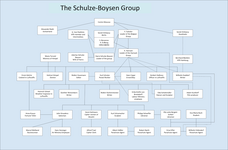

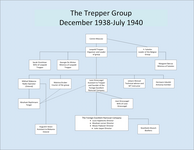

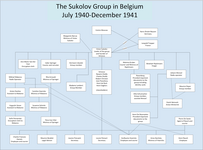

Group organisational diagrams[edit]

The following meticulously researched hierarchy diagrams were created by the Joint security service that consisted of the MI6 and the CIA between 1945 and 31 December 1949.[2]

-

Overall organisational diagram of all anti-fascist and espionage groups by country

-

The Schulze-Boysen group in Germany

-

The Harnack group in Germany

-

Diagram of the Trepper Group in Belgium

-

Gurevich group in Belgium between July 1940 to December 1941 in Belgium

-

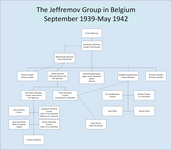

The Jeffremov Group, September 1939 - May 1942 in Belgium

-

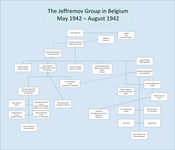

The Jeffremov Group, May 1942 - August 1942 in Belgium

-

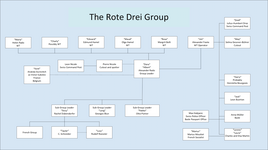

The Rote Drei Group in Switzerland

-

The "Sissy" Group in Switzerland. This group was run by Rachel Dübendorfer

-

The organisation diagram of the "Long" group run by Georges Blun

-

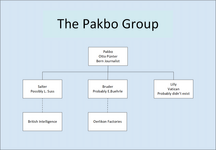

The organisation diagram of the "Pakbo" group run by Otto Pünter

-

The Winterink Group in the Netherlands. It was also known as Group Hilda

-

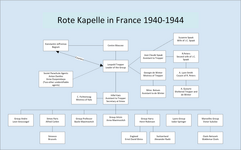

The Rote Kapelle in France between 1940 and 1944. This diagrams details the seven networks run by Leopold Trepper.

-

Group Andre was the 1st espionage group in Leopold Trepper organisation of seven groups. Its purpose was to gather industrial intelligence from enemy wireless communication networks

-

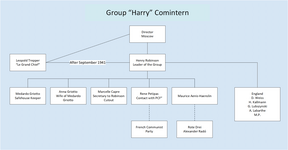

The Harry Group was the 2nd Group in Leopold Trepper's seven espionage networks. This group collected espionage secrets from French military and political circles, e.g. Vichy, Vichy intelligence Deuxième Bureau and Gaullist circles.

-

Organisation diagram of the "Professor" as the 3rd group in Leopold Trepper organisation of seven groups. Professor was the alias of Johann Wenzel. The "Artzin" group was the 4th group in the Trepper organisation and was run by Anna Maximovitch who collected intelligence from French clerical and royalist circles. The "Professor" group, run by Basile Maximovitch collected intelligence from German Wehrmacht and White Russian emigrant groups.

-

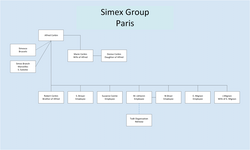

The Simex group was the 5th espionage group in Leopold Trepper organisation of seven groups. It managed finances and gathered intelligence from German firms and the German military

-

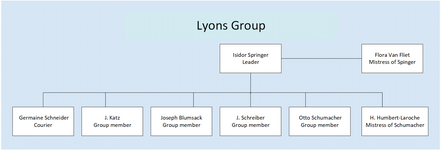

The Lyons or Romeo group was the 6th Group in Leopold Trepper's seven espionage networks. Its purpose was to collect intelligence from US and Belgian diplomats.

-

The 7th Group. In January 1942, Trepper ordered Anatoly Gurevich to travel to Marseilles and establish a new branch office of Simex to enable the recruitment of a new espionage network.[3]

-

The French and UK espionage network of Henry Robinson that was taken over by Trepper in September 1941.

Key[edit]

- If a person was associated with a group, then they are shaded.

- If they joined one group and left to join another, perhaps because the first group was disrupted, then the second group is detailed in notes and they are shaded based on the first group.

- If they worked for Soviet intelligence and built a group, then they are shaded as Soviet intelligence agents.

| Country | Colour | Group | Colour | Group | Colour | Group | Colour | Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Schulze-Boysen Group | Harnack Group | von Scheliha Group | Uhrig Group | ||||

| Bästlein-Jacob-Abshagen Group | Germany military including Gestapo, Funkabwehr | |||||||

| Belgium | Trepper Group | Gurevich Group | Jeffremov Group September 1939-May 1942 | Jeffremov Group May 1942-August 1942 | ||||

| Netherlands | Winterink Group or Group Hilda | |||||||

| France | Group Andre | Lyons Group | Marseilles Group | Ozols Network | ||||

| Switzerland | Rote Drei Group | Sissy Group | Long Group | Pakbo Group | ||||

| Soviet Union | Soviet intelligence officers |

A[edit]

| People of the Red Orchestra | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Life | Employment | Rote Kapelle or military position | Group | Arrested | Fate | Notes | |

| Robert Abshagen | (1911–1944) | Insurance employee, sailor and construction worker | KPD member, Communist | Bästlein-Jacob-Abshagen Group | 19 October 1942 in Hamburg | Sentenced to death by the Volksgerichthof on 2 May 1944. Beheaded in Hamburg on 10 July 10, 1944 | The group that Abshagen was part of was created by Anton Saefkow and eventually held resistance cells in large Hamburg companies.[6] | |

| Alexander Abramson | (1896–?) | Lawyer and economist | Rote Drei | Codenames: Isaak and Sascha[7] | ||||

| Vera Ackermann | Militant communist | Encrypted communications prior to transmission and handed the ciphered text to the Sokols, who were radio operators, for transmission to the Soviets | Trepper Group | Escaped being arrested | [8] (Partial Preview at Google Books) | |||

| Maurice Aenis-Haenslin | KPD member, liaison between Henry Robinson and Rachel Dübendorfer for the Rote Drei in Geneva | Rote Drei Group | Real person was never identified as name was identified through radio traffic. The name fitted two individuals but other facts didn't.[9] | |||||

| Bernhard Almstadt | (1897–1944) | Managing director of the Arbeiter-Sport-Verlag | KPD member. Courier, participated in the dissemination of the illegal paper, Die Innere Front (The Inner Front). | Uhrig Group | 12 July 1944 and sentenced to death on the 19th | Executed on 6 November 1944 in the Brandenburg-Görden penitentiary | [10] | |

| Leonid Abramovich Anulov | (1897–1974) | Soviet agent | Organizer of the Rote Drei in Switzerland | Recalled to the Soviet Union in 1938, received the Order of Lenin and released from office. He was then arrested under Soviet law § 436 and sentenced to 15 years at a work education detention camp. | [11][12] | |||

| Rita Arnould | (1914–1943) | Housewife | Courier | Trepper Group | Rue des Atrebates 101, Brussels on 13 December 1941 | Death sentence in April 1943 | [13] Rita Arnould (née Bloch) became an informer after being captured by the SS in Brussels. She betrayed the Gurevich group in Brussels, forcing many of its members to flee to France and other minor characters to stay hidden. Arnould was, nonetheless, executed on 20 August 1943 at Plötzensee Prison.[14] | |

B[edit]

| People of the Red Orchestra | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Life | Employment | Rote Kapelle or military position | Group | Arrested | Fate | Notes | |

| Otto Bach | Member of International Labour Office in Geneva | Facilitated introductions | Rote Drei | Member of the German Chamber of Commerce in Paris. Worked with Heinz Pannwitz.[15] | ||||

| Margarete Barcza | (1912–1985)[16] | Mistress and later wife of Anatoly Gurevich.[17] | ||||||

| Robert Barth | (1910–1945) | Typesetter | Communist and parachute agent | Schulze-Boysen Group | Arrested October 1942 | Landed with Albert Hoessler[18] | ||

| Bernhard Bästlein | (1894–1944) | Precision mechanic | KPD member, Communist. Built the Bästlein-Jacob-Abshagen Group. | Bästlein-Jacob-Abshagen Group | 30 May 1944 and sentenced to death on 5 September | 18 September 1944 beheaded with a hatchet | Linked to Harnack Group via Wilhelm Guddorf. Also linked to Schulze-Boysen and Uhrig people.[19] | |

| Arnold Bauer | (1909–2006) | Writer | Communist and KPD member | Schulze-Boysen Group | Survived the war | [20] | ||

| Carl Baumann | (1912–1996) | Artist | Schulze-Boysen Group | Arrested in autumn 1942 and sent to the Eastern Front in 1943 | Wounded in 1944 and captured by Soviet forces, but survived the war | Baumann created a now famous painting called Rote Kapelle 1941 ref number Inv-Nr. 1967 LM, now located in the Stadtmuseum in Münster in which he portrays Harro Schulze-Boysen, Walter Küchenmeister and Kurt Schumacher as architects building a bridge away from Nazism.[21] | ||

| Anna Becker | 11 August 1943 in the industrial yard of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp | Mother of Friedrich Beuthke's wife, Charlotte. Killed as one of the seven members by what the Nazi's called Sippenhaft, where they were inclined to kill the whole family in revenge, when a Red Orchestra member was discovered. Shot without trial.[22] | ||||||

| Emil Becker | 11 August 1943 in the industrial yard of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp | Father of Friedrich Beuthke's wife, Charlotte. Killed as one of the seven members by what the Nazis called Sippenhaft, where they were inclined to kill the whole family in revenge, when a Red Orchestra member was discovered.[22] | ||||||

| Karl Behrens | (1909–1943) | Tool designer | Communist Black Front member, then member KPD | Harnack Group | 16 September 1942. The 2nd senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced on 18 January 1943, the death penalty | Killed on 13 May 1943 in Plötzensee Prison | [23] | |

| Clare Behrens | (1915–2011) | Tailor | Survived the war | Wife of Karl Behrens | ||||

| Willy Berg | Gestapo Kriminalinspector | Sonderkommando Pannwitz. Monitored Trepper and Gurevitch. | Worked for Heinz Pannwitz[24] | |||||

| Helene Berger | (1898–?) | Austrian economist | Supplied intelligence to Rachel Dübendorfer | Rote Drei | [25] | |||

| Hanna Berger (née Johanna Elisabeth Hochleitner-Köllchen) | (1910–1962) | Teacher, director, theatre director | Enabling subversive communist gatherings in her home. KPD member | Schulze-Boysen Group | 1942, suspected of preparing to commit high treason and sentenced to two years in concentration camp, but was acquitted after several months on 21 August 1943 | Survived the war | [26] | |

| Liane Berkowitz | (1923–1943) | Student | Took part in pamphleteering against The Soviet Paradise | Schulze-Boysen Group | Arrested on 26 September 1942. The 2nd senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced on 20 January 1943, the death penalty | Executed on 20 January 1943 at Plötzensee Prison | [27] | |

| Sergei Bessonov |

(1892–1941) |

Foreign Intelligence Unit of the Soviet Embassy in Berlin | Created the Harro Schulze-Boysen Group. | Convinced Harnack to work for the Soviets. Murdered by the Soviet secret police in Stalin's Medvedev Forest massacre on 11 September 1941. | ||||

| Maurice Beublet |

(?–1943) |

Belgian lawyer | Simexco legal advisor | Gurevich Group | 4 December 1942 in Brussels | 28 July 1943 in Plötzensee Prison | [25] | |

| Leon Beurton | (1914–1997) | Soviet agent | Chief cipher expert for Alexander Radó. Trained by Ursula Hamburger in WT procedures. | Rote Drei Group | Survived the war. | Married to Ursula Kuczynski.[9] Codenamed William Miller, John, Fenton.[28] | ||

| Anna Beuthke | (1883–1943) | Mother of the Beuthke family | KPD, Communist. Member of the Little Moscow garden colony. Also called Garden Friends. |

Arrested 11 August 1943 in the industrial yard of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.[29] |

Killed by what the Nazis called Sippenhaft, whereby they were inclined to kill the whole family in revenge whenever a Red Orchestra member was discovered. Shot without trial.[22] | |||

| Ernst Beuthke | (1903–1943) | No profession, warehouse man. Only son of the Beuthke family who held no profession.[22] | Communist KPD Anti-Fascist fighter in Spain, and Germany fighting the SA. Soviet parachutist. | Member of the Little Moscow garden colony. Also called Garden Friends. Hid in Charlotte Hundt's home upon arrival. | Arrested with his wife after returning from the USSR and exposing himself in the Little Moscow garden colony. | 11 August 1943 in the industrial yard of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp | Killed by what the Nazis called Sippenhaft, whereby they were inclined to kill the whole family in revenge whenever a Red Orchestra member was discovered. Shot without trial.[30] | |

| Friedrich Beuthke | (1906–1943) | Welder. Youngest son of the Beuthke family.[22] | KPD member, Communist. Member of the Little Moscow garden colony. | Executed on 11 August 1943 in the industrial yard of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. |

Killed by what the Nazis called Sippenhaft, whereby they were inclined to kill the whole family in revenge whenever a Red Orchestra member was discovered. Shot without trial.[31] | |||

| Richard Beuthke | (1880–1943) | Servant and turner. Father of the Beuthke family.[22] | KPD member, Communist. Member of the Little Moscow garden colony. | Executed on 11 August 1943 in the industrial yard of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp |

Killed by what the Nazis called Sippenhaft, whereby they were inclined to kill the whole family in revenge whenever a Red Orchestra member was discovered. Shot without trial. [32] | |||

| Walter Beuthke | (1904–1943) | Precision mechanic. Second eldest son of the Beuthke family.[22] | KPD member, Communist. Member of the Little Moscow garden colony. | Executed on 11 August 1943 in the industrial yard of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp |

Killed by what the Nazis called Sippenhaft, whereby they were inclined to kill the whole family in revenge whenever a Red Orchestra member was discovered. Shot without trial.[33] | |||

| Charlotte Beuthke | (1909–1943) | Communist KPD member of the Little Moscow garden colony. Shot without trial.[22] | Executed on 11 August 1943 in the industrial yard of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. | Married to Walter Beuthke.[34] | ||||

| Mario Bianchi | (1909–?) | Physician, ear, nose and throat specialist | Kept a safehouse that hid a number of contacts. Later, hid Alexander and Helen Radó after Rote Drei was broken up. | Rote Drei | Survived the war | [35] | ||

| Lotte Bischoff (née Charlotte Wielepp) | (1901–1994) | stenographer | KPD, participated in the dissemination of the illegal paper, Die Innere Front. SED functionary | Saefkov-Jacob-Bästlein Group | Survived the war | In contact with Wilhelm Knöchel, Robert Uhrig, and Kurt and Elisabeth Schumacher.[36] | ||

| Kurt Bietzke | (1894–1943) | Painter | KPD co-founder. Procured illegal quarters, got passports, money and ration cards. | Tucholla group, Red Mountain Climbers | Sentenced to death by the People's Court (Germany) in July 1942 | 17 August 1943 in Plötzensee Prison. | [37] | |

| Herbert Bittcher | (1908–1944) | Foreman | SPD. Later became a communist and joined the KPD | Bästlein-Jacob-Abshagen Group | Arrested by Gestapo | On 1 January 1944 sentenced to death for the "preparation for high treason". Executed in January 1944 in the Brandenburg-Görden Prison | [38] | |

| Joseph Blumsack | Member of the foreign workers section of the Communist Party of Belgium | Courier between Brussels and Paris | Trepper Group | Arrested 7 January 1943 and deported to Germany. |

Rumoured to have survived but no evidence of this. |

Married to Renée Clais-Blumsack.[35] | ||

| Georges Blun | (1893–1999) | French journalist from Le Monde | Soviet agent | Rote Drei Group. | Survived the war | Directed small Blun network of six people in Switzerland. Codename Long. Secrets offered by Blun could not match the quality of the Lucy secrets, but still a very important member of the Red Three Group. Survived the war.[9] | ||

| Suzanne Boisson | (1918–?) | Courier | Gurevich Group. | 13 December 1941 | Unknown | [39] | ||

| Karl Böhme | (1914–1943) | Commercial clerk | Tried to organise the repair of the radio located at Hans Coppi | Schulze-Boysen Group |

Arrested on 23 October 1942 in Berlin. The 2nd Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced the death penalty on 30 January 1943 "for preparation for high treason in a unit with favorability of the enemy and for aiding espionage". |

Wife Margarete Böhme was also picked up by the Gestapo and killed. | ||

| Anton Börner | Soviet intelligence agent | Soviet parachutist | KPD | Trained as an upholsterer. Captured by the Gestapo upon landing. | ||||

| Wilhelm Bösch | Died 10 April 1945 | Locksmith | Communist KPD member. Collected money and food for persecuted colleagues. | AEG turbine factory group | 21 March 1945 sentenced to death by Berlin Superior court | Murdered in Plötzensee Prison on 10 April 1945 | [40] | |

| Hermann Böse | (1871–1943) | Music teacher and conductor | Communist, KPD member | Bästlein-Jacob-Abshagen Group | Sent to the KZ Mißler concentration camp | [41] | ||

| Paul Böttcher | (1891–1975) | Communist politician, MP, Journalist | Passed information between Christian Schneider and Alexander Radó | Rote Drei Group | 1933 taken into 10 months protective custody by the Nazis, released and emigrated to Switzerland | Survived the war | Married to Rachel Dübendorfer. Codename Paul, codenamed Hans Saalbach. | |

| Margrit Bolli | (1919–2017) | Dancer | Radio operator | Rote Drei | 13 October 1943 and sentenced to 10 months in prison | Survived the war | Code name Rosa, Schatz-Bolli,Schwarz-Boili. Recruited by Alexander Radó and trained in Wireless Telegraphy by Alexander Foote.[43] | |

| Cato Bontjes van Beek | (1920–1943) | Artist. | Distributed illegal writings and leaflets | Schulze-Boysen Group | 20 September 1942. The 2nd senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced the death penalty on 18 January 1943 | 18 January 1943 sentenced to death for high treason and guillotined. A personal clemency to Hitler was refused. | [44] Started opposing Hitler when she was 13 years old when she heard a broadcast from Hitler in 1933 in the one nation speech. | |

| Mietje Bontjes van Beek | (1922–2012) | Artist and author | Schulze-Boysen Group | Survived the war | Not actively involved in the resistance. Occasionally took food and cigarettes along with her sister Cato to French forced labourers in Berlin.[45] | |||

| Jan Bontjes van Beek | (1899–1969) | Ceramist and sculptor | Schulze-Boysen Group | 20 September 1942 in Berlin | Survived the war | Became famous sculptor and ceramist after the war, with a particular focus on vases. Fringe member of the group through his daughter Cato[46] | ||

| Henriette Bourgeois | (1917–?) | stenographer | Radio operator | Rote Drei Group | Survived the war | Codename Harry[47] | ||

| Elsa Boysen | (1883–1963) | Schulze-Boysen Group | 26 September 1942 | Survived the war | Aunt of Harro Schulze-Boysen.[48] | |||

| Walter Bremer | (1904–1995) | Surveying student and Police officer | Helped produce the Die Innere Front newspaper | Survived the war | [49] | |||

| Robert Breyer | Painter and illustrator | Trepper Group | 25 November 1942 in Paris | Hanged in July 1943 in Plötzensee Prison | ||||

| Cay-Hugo Graf von Brockdorff | (1915–1999) | Sculptor | Schulze-Boysen group | Arrested in 1943 on the Eastern Front and sent to a Strafbataillon | Survived the war and married resistance fighter Eva Lippold. Marie Hübner was maid of honor. | [50] | ||

| Erika Gräfin von Brockdorff | (1911–1943) | Office worker | Radio experimenter, used own house as communication centre for Hans Coppi | Schulze-Boysen Group | 16 September 1942 arrested and sentenced to 10 years. The 2nd senate of the Reichskriegsgericht sentenced him on 21 April 1943 to four years in prison for preparation for high treason. Hitler turned penalty into death sentence. | 13 May 1943, strangled with a rope attached to a meathook in Plötzensee Prison | [51] | |

| Eva-Maria Buch | (1921–1943) | Interpreter, translator, bookseller and student | Translation of individual pamphlets and the Die Innere Front newspaper into French | Schulze-Boysen Group | Arrested on 11 October 1942 | On 3 February 1943 sentenced by the 2nd Reichskriegsgericht to death for the preparation of a high-treasonous enterprise and because of enemy favouritism and executed in Plötzensee Prison. | [52] | |

| Walter Budeus | (1902–1944) | Machinist | Communist, former KPD member. Built illegal group in northern Berlin to report armaments production and to disseminate leaflets. | Uhrig Group | February 1942 | 21 August 1944 beheaded | [53] | |

| Hugo Buschmann |

(1899–1983)[54] |

Industrialist. President of the Eternit AG, a construction materials company. | Worked as an informant for Schulze-Boysen | Schulze-Boysen Group |

Survived the war |

Travelled as Leo Buschmann[55] | ||

C[edit]

| People of the Red Orchestra | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Life | Employment | Rote Kapelle or military position | Group | Arrested | Fate | Notes | |

| Marcelle Capre | (1914–?) | Soviet intelligence officer | Acted as a cutout for agent Jerome. Provided intelligence on French aircraft. | Trepper Group | Code name Martha. Hid Germaine Schneider in her apartment. Assistant to Henry Robinson.[56] | |||

| Robert Jean Christen | (1898–?) | Gurevich Group | 25 November 1942 in Brussels | Survived the war | Simexco shareholder[47] | |||

| Joséphine Clais | (?–1945) | Courier | Jeffremov Group | January 1943 and sent to Breendonk prison camp | Died in early 1945 in Ravensbrück concentration camp | Married name Joséphine Verhimst. Sister of Germaine Schneider and Reneé Clais. Recruited by Germaine.[57] | ||

| Reneé Clais (Blumsack) | (1907–1945) | Courier between Brussels and Paris | Trepper Group | Arrested on 7 January 1943 in Brussels | 10 March 1945 in the Mauthausen concentration camp | Wife of Joseph Blumsack. Sister of Germaine Schneider and Joséphine Clais. Recruited by Germaine.[35] | ||

| Suzanne Cointe | (1905–1943) | Piano teacher. Secretary to Alfred Corbin at Simex | Trepper Group | 19 November 1942 in Paris | July 1943 in Plötzensee Prison | [58] | ||

| Frieda Coppi | Tailor | Harnack Group | 12 September 1942 in Berlin | Mother of Hans Coppi. Killed by what the Nazis called Sippenhaft, whereby they were inclined to kill the entire family of any Red Orchestra member who was uncovered. | ||||

| Hans Coppi | (1916–1942) | Student | Disributing phamplets, later establishing a radio link to the Soviet Union | Harnack group | Arrested on 12 September 1942 in Berlin. On 19 December 1942, the 3rd Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced the death penalty | Death penalty 19 December 1942 | Introduced to Schulze-Boysen via Heinrich Scheel.[59] Ran the Coro group. Code name Strahlmann.[60] | |

| Hilde Coppi | (1909–1943) | Clerk | KPD | Harnack Group | 12 September 1942 in Berlin. On 20 January 1943, the 2nd senate of the Reichskriegsgericht pronounced the death penalty. | Death penalty on 20 January 1943 | Wife of Hans Coppi. Mother of Hans Coppi Jr. (born 27 November 1942)[59] | |

| Kurt Coppi | Harnack Group | 12 September 1942 in Berlin | ||||||

| Robert Coppi | (1882–1960) | Painter specialising in lacquer and gilding | KPD | Harnack Group | 12 September 1942 | Father of Hans Coppi. Killed by what the Nazis called Sippenhaft, whereby they were inclined to kill the entire family of any Red Orchestra member who was uncovered. | ||

| Alfred Corbin | (1919–1943) | French commercial director | Ran the 5th Trepper sub-network. Managing director of Simex in Paris. Courier | Trepper Group | 19 November 1942 in Paris | 28 July 1943 in Plötzensee Prison | Initially never knew anything about the network but was gradually drawn in over many months, eventually becoming a core member.[61] | |

| Denise Corbin | 25 November 1942 | Fresnes Prison | Wife of Robert Corbin. Killed by what the Nazis called Sippenhaft, whereby they were inclined to kill the entire family of any Red Orchestra member who was uncovered. | |||||

| Marie Corbin | 26 November 1942 | Ravensbrück concentration camp. |

Killed by what the Nazis called Sippenhaft, whereby they were inclined to kill the entire family of any Red Orchestra member who was uncovered. | |||||

| Robert Corbin | Liaison between Alfred Corbin and the Organisation Todt | Trepper Group | 19 November 1942 in Paris | 8 March 1943 death penalty | Denise Corbin was his wife. Brother of Alfred Corbin. uncovered. | |||

| Fritz Cremer | (1906–1993) | Sculptor. Soldier between 1940 and 1944. | KPD member, Communist | Schulze-Boysen Group | Survived the war | Husband of Hanna Berger, who, although arrested as part of Schulze-Boysen group, escaped in 1944. Both Cremer and Berger survived the war.[63] Cremer had strong contacts with Walter Küchenmeister and Kurt Schumacher | ||

| Buntea Crupnic | (1911–2002) | Lawyer | Communist. Provisioned safehouses in the Brussels area and responsible to Elizabeth Depelsenaire. | Jeffremov Group | Survived the war | Code name Irma Salno, Irene Sadnow, Andree, Yvonne[61][64] | ||

D[edit]

| People of the Red Orchestra | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Life | Employment | Rote Kapelle or military position | Group | Arrested | Fate | Notes | |

| Charles Francois Daniels | (1911–?) | Businessman | Courier between Simexco in Brussels and Simex in Paris | Gurevich Group | Business associate of Guillaume Hoorickx and Heinrich Rauch.[65] | |||

| Anton Danilov | Belgian communist, Soviet agent | Secret writing specialist to prepare identity papers | Gurevich Group | 12 December 1941 in Brussels while transmitting | Believed to have been executed in or around 1943. | Code name: Antonio, Desmet, de Smet, de Smith Assistant to Anton Makarov. Assumed to be David Kamy in disguise.[66] | ||

| Elizabeth Depelsenaire | (1913–1998) | Lawyer, feminist | Belgian Communist, Intelligence officer | Jeffremov Group | Arrested July 1942 | Survived the war | Worked in the group in 1941 and 1942.[67] | |

| Werner Dissel | (1912–2003) | Actor | Volunteered into the Wehrmacht to betray them. | Schulze-Boysen group | Escaped detection | Survived the war | Helped to publish the magazine of the Schulze-Boysen Group called The Adversary. Was a personnel friend of Harro Schulze-Boysen.[68] | |

| Rachel Dobrik | (1908–?) | Rote Drei accountant | Supplied monies to Rachel Dübendorfer from an American account | Rote Drei | Dobrik warned Alexander Radó that the Swiss were going to arrest Rote Drei members.[69] | |||

| Martha Dodd | (1908–1990) | Writer | Soviet agent | Harnack group | Survived the war | [70] | ||

| Charles Drailly | (1901–1945) | Banker and commercial expert | Became director of Simexco in March 1941. | Gurevich Group then worked for the Rote Drei | Arrested on 25 November 1942 | Died of Typhus on 4 January 1945 Mauthausen concentration camp | Drailly was aware of the activities of the Belgian intelligence networks but did not actively take part in them.[71] | |

| Germaine Drailly | (1899–1945) | Rote Drei | Arrested 26 November 1942 and deported to Berlin | On 13 May 1945, sentenced to death by the Reichskriegsgericht. | Married to Nazarin Drailly. | |||

| Nazarin Drailly | (1900–1943) | Helped to establish Simexco | Took over management of Simexco after Gurevich left for France. | Gurevich Group, Rote Drei | 6 January 1943 Brussels. | Tortured with dogs who ripped his legs to shreds and they had to be amputated. 28 July 1943 in Plötzensee Prison | Brother of Charles Drailly. Actively involved in the collection of military and industrial intelligence.[72] | |

| Solange Drailly | (born 1 February 1926) | Rote Drei | Arrested as part of the Simexco round up by the Gestapo in November 1942. | Released for lack of evidence. Survived the war. | Daughter of Nazarin and Germaine Drailly. | |||

| Rachel Dübendorfer | (1900–1973) | Secretary of International Labour Organization | Polish Comintern representative | Rote Drei | Survived the war. | Code name was Sissy.[73] | ||

| Jutta Dubinsky | (1917–1985) | KPD/SED | Wilhelm Schürmann-Horster group and later Hans Coppi group | 21 October 1942 in Berlin | The 2nd senate of the People's Court sentenced on 21 August 1943 to eight years in prison. Survived the war. | Became involved with Harnack through the Fritz Cremer, Cay-Hugo von Brockdorff and Wolfgang Thiess. | ||

| Viktor Dubinsky | (1912–1942) | Student | KPD/SED | Wilhelm Schürmann-Horster group and later Hans Coppi group | 26 October 1942 in Guben | 21 April 1943 sentenced to five years in prison for preparation of High Treason. | Became involved with Harnack through the Fritz Cremer, Cay-Hugo von Brockdorff and Wolfgang Thiess. | |

| Jacques Duclos | (1896–1975) | French Communist politician | PKF, Coordinator of the Resistance. Managed connections to Moscow | Trepper group | Survived the war | [74] | ||

E[edit]

| People of the Red Orchestra | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Life | Employment | Rote Kapelle or military position | Group | Arrested | Fate | Notes | |

| Modeste Ehrlich | Trepper Group | December 1942 | Sent to a concentration camp | Betrayed by Trepper to save his life.[75] | ||||

| Erna Eifler | (1908–1944) | Stenographer | Soviet parachutist | KPD, Communist agent | Arrested on 15 October 1942 in Hamburg | On 8 April or 7 June 1944 shot dead in Ravensbrück concentration camp | Arrived in Germany with Wilhelm Fellendorf in May 1942 and were to provide communication for the von Scheliha group but Harnack heard of their arrival in Hamburg.[76] | |

| Charlotte Eisenblätter | (1903–1944) | Chief secretary in a large company | Creating leaflets and writing addresses. | Uhrig group | Arrested in February 1942, she was sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp | On the 10 July 1944, sentenced to death for preparing for high treason | [77] | |

| Horst von Einsiedel | (1905–1947) | Lawyer and economist | Kreisau group | Worked with Arvid Harnack in the 1930s to build a resistance group. | ||||

| Ina Ender | (1917–2008) | Seamstress andmodel | Courier | Schulze-Boysen and Harnack Groups through Hans Coppi who ran the Coro Group | Arrested September 1942 | In July 1943 sentenced to six years in prison by the Reichskriegsgericht for assisting to disintegrate the military forces (distributing leaflets). Ender survived the war | Communited gossip from the couturier shop she worked in that was attended by Eve Braun, to Schulze-Boysen. Married Hans Lautenschläger on 14 September 1936. In December 1952, she married civil servant Siegfried Ender,[78][79] | |

| Alexander Erdberg | (1909–1961) | Soviet intelligence agent. | Acted as contact between Moscow and Harnack Schulze-Boysen Groups | Recruited Harnack Group, Created Schulze-Boysen Group | Survived the war | Worked for the Foreign Intelligence Unit of the Soviet Embassy in Berlin.[80] | ||

F[edit]

| People of the Red Orchestra | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Life | Employment | Rote Kapelle or military position | Group | Arrested | Fate | Notes | |

| Katharina Fellendorf | (1884–1944) | Housewife | Mother of Wilhelm Fellendorf.

Killed by what the Nazis called Sippenhaft, where they were inclined to kill the entire family of any Red Orchestra member who was uncovered.[81] | |||||

| Wilhelm Fellendorf | (1903–1944) | Locksmith, driver | Soviet agent | Schulze-Boysen and Bästlein-Jacob-Abshagen group | 15 October 1942 | 28 October 1942 in Hamburg | Came to Germany in May 1942 with Erna Eifler as a parachutist to collect intelligence.[81] | |

| Wilhem Franz Flicke | (1897–1957) | German Wehrmacht soldier and cryptanalyst, later author | Worked on the cryptanalysis of Rote Drei messages | Cipher Department of the High Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW/Chi) | Flicke wrote two books. The second one was called War Secrets in the Ether that described an OKW/Chi intercept station at Lauf.[82] The first and most salient book was on the subject of the Die Rote Kapelle.[83] The information is no longer considered fully accurate and is at times, misleading.[84] | |||

| Alexander Foote | (1905–1957) | Radio operator | Radio operator | Rote Drei Group | In November 1943 imprisoned by Swiss who picked up his radio by DF-ing it. Released September 1944 | Survived the war | Code names:Jim, Alfred, Major Granatow, Alfred Feodorovich Capidus, Alexander Alexandrovich Dymov, John South, Albert Mueller. Worked with Ursula Beurton then Alexander Radó. Had many code names.[85] | |

| Karl Frank | (1906–1944) | Cabinetmaker and politician | KPD member, produced papers and pamphlets attacking the Nazi regime, calling for acts of resistance. | Uhrig Group | Arrested in May 1942 and in June 1944, sent to the Sachsenhausen and Landsberg concentration camps. | Executed on August 21, 1944 at the Brandenburg-Görden Prison. | Frank was in the communist group that created resistance cells in factories around Berlin and Hamburg. The cells were coordinated by Robert Uhrig. | |

G[edit]

| People of the Red Orchestra | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Life | Employment | Rote Kapelle or military position | Group | Arrested | Fate | Notes | |

| Erwin Gehrts | (1890–1943) | Journalist, Colonel in Luftwaffe | Communist, Gehrts passed all his Luftwaffe documents and interesting events to Shulze-Boysen who passed some to Harnack | Shulze-Boysen Group | 9 October 1942 | Reichskriegsgericht announced death penalty 10 January 1943 | One of the most important members of the Shulze-Boysen Group.[86] | |

| Walter Gersmann | (1914–1942) | Gardener | KPD member and Soviet intelligence agent. Soviet parachutist. | Arrested by the Gestapo on 18 or 19 May 1942, the day after parachuting from a plane near the village of Dittau | Executed at the end of 1942 | Trained as an agent by the GRU and sent to Europe. Betrayed members of the Bästlein-Jacob-Abshagen Group after being turned by the Gestapo after almost a year of captivity.[87] | ||

| Selma Gessner–Bührer | (1916–1974) | Swiss Soviet agent | Worked for Maria Josefovna Poliakova in Switzerland in 1936. | Rote Drei | Survived the war | Recalled in 1941 by Moscow to provide assistance to Alexander Radó. Acted as a cutout between Jules Humbert-Droz and Alexander Foote.[88] | ||

| Karl Giering | (1900–1945) | Gestapo agent and police officer | First head of Sonderkommando Rote Kapelle. | Died of throat cancer before the end of the war. | Kriminalrat in AMT, Abteilung II, RSHA. Leading detective in the search for Soviet agents in Belgium and France. Was replaced by Heinz Pannwitz in August 1943 as he was dying of cancer.[89] | |||

| Pierre Giraud | (1914–1943) | Trepper Group | December 1942 in Paris | Committed suicide in early 1943 at Fresnes. Husband of Suzanne Giraud. | [90] | |||

| Suzanne Giraud | (1910–?) | Custodian of a wireless telegraphy set located in Le Pecq. Worked as a courier transporting documents between the French communists and the Trepper Group. | Trepper Group | Arrested in 1942 | Presumably executed in 1942 or 1943 | Wife of Pierre Giraud, who was recruited by Léon Grossvogel. Codename was Lucy and worked under the name of Lucienne Giraud, Trepper's connection to the French Communist Party.[89] | ||

| Robert Giraud | (1906–1943) | Courier | Trepper Group | Giraud was the main liaison between Trepper and executive committee of the French Communist Party.[91] | ||||

| Hans Bernd Gisevius | (1904–1974) | German diplomat and intelligence officer | Informant | Rote Drei | Survived the war. | Gisevius liaison in Zürich between Allen Dulles, station chief for the American OSS and the German Resistance forces in Germany. Rudolf Roessler identified Gisevius as a source to a friend after the war.[92] | ||

| Walter Glass | (1889–1956) | Pattern shop owner | Housed and fed Bernhard Bästlein with his daughters in 1944 at his own apartment | 5 July 1944 | VGH ruling on 1 November 1944, sentenced to four years in jail | Glass was the father of Lucie Nix and Vera Wulff. | ||

| Carl Friedrich Goerdeler | (1884–1945) | German politician | Informant | Rote Drei | 12 August 1944 | Hanged on 2 February 1945 in Plötzensee Prison | Joined the 20 July plot to assassinate Hitler. He is one of the four Rote Drei sources in Germany named by Rudolf Roessler.[93] | |

| Ursula Goetze | (1916–1943) | Student | Apartment was used for a number of secret meetings. | Schulze-Boysen and Harnack groups | 15 October 1942 in Berlin | 18 January 1943, the 2nd senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced death penalty for conspiracy to commit high treason and favouring the enemy | [94][95] | |

| Sarah Goldberg | (1921–2003) | Radio operator in Belgium. Recruited by Hermann Isbutzki. | Trepper Group | 4 June 1943 | Deported to Germany and then Auschwitz concentration camp | After the Red Orchestra was destroyed in Belgium in 1943, transferred to work with Jewish partisans in Brussels. Rescued on 23 April 1945. Survived the war. Founding member of Belgian section of Amnesty International.[96] | ||

| Joseph Goldenberg | Arrested in early 1942 | Fort Breendonk concentration camp from September 1942 to March 1943, died there on 13 April 1943 following an "interrogation". | ||||||

| Herbert Gollnow | (1911–1943) | Consular Secretary, at the Federal Foreign Office | Later, lieutenant in the Luftwaffe working as a Liaison officer from the Abwehr | Harnack Group | Arrested on 19 October 1942 in Berlin | Reichskriegsgericht announced death penalty for conspiracy to commit high treason and favouring the enemy on 19 December 1942. | One of the core members of Harnack Group[97] | |

| Otto Gollnow | (1923–1944) | Bank apprentice, soldier | 26 September 1942 in Berlin | Reichskriegsgericht announced death penalty for undermining the military, received a six-year prison sentence. | ||||

| Daniël Goulooze | (1901–1965) | Director of the Communist Party of the Netherlands | Radio operator. Liaison officer between CPN and the Communist International in Moscow. | Hilda Group | Arrested sometime in 1943 | Survived the war. | Codenames:Daan.Not charged as a terrorist by as a spy and survived by changing his name in the concentration camp.[98][99] | |

| Max Grabowski | (1897–1981) | Painter and decorator | Participated in the dissemination of the illegal paper, Die Innere Front (The Inner Front) | Schulze-Boysen Group | Brother of Otto Grabowski. Printed the Die Innere Front in his paint workshop.[100][101] | |||

| Otto Grabowski | (1892–1961) | Participated in the dissemination of the illegal paper, Zeitung Neuköllner Sturmfahne | Schulze-Boysen Group | Brother of Max Grabowski. Founder of Die Innere Front[102] | ||||

| Herbert Grasse | (1910–1942) | Printer | KJVD, KPD. Participated in the productions of the illegal paper, Zeitung Neuköllner Sturmfahne | Wilhelm Schürmann-Horster group | Arrested on 23 October 1942 in Berlin | Committed suicide the day after his arrest | Had close links with the group around Wilhelm Schürmann-Horster and later had contact with John Sieg. Later pushed for joint actions in the AEG factory amongst workers who were resisting.[103] | |

| John Graudenz | (1884–1942) | Journalist, photographer, sales representative | In charge of the technical aspects of the producing the AGIS leaflets. Later helped Schulze Boysen organise intelligence. | Schulze Boysen Group | 12 September 1942 in Berlin | On 19 December 1942 the 3rd senate of the Reichskriegsgericht sentenced him to the death penalty because of preparation for high treason, enemy favour, destruction of the military force and espionage | [104] | |

| Karin Graudenz | Schulze Boysen Group |

Arrested on 12 September 1942 in Berlin; released after two weeks. |

Daughter of John Graudenz. Also called Karin Reetz after being married. | |||||

| Silva Graudenz | Schulze Boysen Group | Arrested on 12 September 1942 in Berlin; released after two weeks. | Daughter of John Graudenz | |||||

| Toni Graudenz | (died 1985) | Press photographer | Schulze-Boysen group | Arrested on 12 September 1942 in Berlin | On the 12 September 1942 in Berlin the 2nd senate of the Reichskriegsgericht sentenced to three years in prison for listening to enemy transmitter and omission of an advertisement. Survived the war. | Third wife of John Graudenz | ||

| Manfred von Grimm | (1911–?) | Long Group | Arrested October 1942 | Survived the war. Became the Minister of Cultural Affairs in Lower Saxony. | Codenamed Grau for Rote Drei. Worked for Polish intelligence.[105] | |||

| Adolf Grimme | (1889–1963) | Prussian Minister of Science, Art and Education | Sent letters to university professors and distributed pamphlets | Harnack group | Avoided the death penalty in 1943 by informing on the Red Orchestra. The 2nd Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht sentenced him on 2 February 1943 for the preparation of a treasonous enterprise and because of enemy privileges to three years penitentiary | Survived the war | Friends with Adam Kuckhoff.[106] | |

| Maria Grimme | Harnack group | Survived the war | Wife of Adolf Grimme.[106] | |||||

| Anna Griotto | Courier for Henry Robinson group in France | Own house used to hold meeting between Henry Robinson and Trepper Group members | Trepper Group |

Survived the war |

Wife of Medardo Griotto.[107] | |||

| Medardo Griotto | (1901–1943) | Engraver | Produce fake documents, also operated a safe house | Trepper group | Reichskriegsgericht sentenced him to death in March 1943. | Executed on 28 July 1943 in Plötzensee Prison | Suspected of being Henry Robinson's main assistant.[107] | |

| Léon Grossvogel | (1904–?) | Electrician and manager | Ran the 1st Trepper sub-network. Provided intelligence concerning industry and economy. Responsible for the communications networks of the Trepper Group. | Trepper Group | Arrested in 1943 by Gestapo | Possibly executed in Fresnes Prison, possibly survived the war | Husband of Jeanne Grossvogel-Pesant. Worked at Le Roi du Caoutchouc. Later created the Foreign Excellent Rain Coat Company with Jules Jaspar.[107] | |

| Jeanne Grossvogel-Pesant | (1901–1943) | Manager of ostend branch of Le Roi du Caoutchouc | Ran the 3rd Trepper sub-network

Later created the Foreign Excellent Rain Coat Company with Jules Jaspar and her husband. |

Trepper Group | Arrested 25 November 1942 | Executed in July 1943 in Plötzensee Prison | Wife of Léon Grossvogel[107] | |

| Malvina Gruber | (1900–?) | Courier between Paris and Brussels and Cutout between Rajchmann and Trepper. | Gurevich Group | Arrested in Brussels on 12 October 1942 | Protected by the Sonderkommando, used to discover other agents in Brussels and Paris. In August 1947 in prison in Belgium, later sentenced to 10 years imprisonment in February 1949 by court martial in Brussels, released December 1951. | Wife of Adolf Gruber. Mistress of Abraham Rajchmann, the forger.[108] In 1953, Gruber still engaged in espionage.[108] | ||

| Wilhelm Guddorf | (1902–1943) | Journalist and writer | Communist | Harnack group | Arrested on 10 October 1942 and sentenced to death in February 1943. The 2nd Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced on 3 February 1943 the death sentence for preparation for high treason and because of enemy favouritism | Executed at Plötzensee Prison in Berlin on 13 May | Important member of Schulze-Boysen Group as well.[109] | |

| Hilde Guddorf | (1907–1980) | Shorthand typist, later GDR politician | Communist member of Young Communist League of Germany and Communist Party of Germany | Harnack Group | Survived the war | Husband of Wilhelm Guddorf. Worked with the Uhrig group.[110] | ||

| Anatoly Gurevich | (1913–2009) | Soviet agent. Provided intelligence to Trepper from François Darlan and the Girauds. | Ran the 7th Trepper sub-network. | Trepper Group | 12 November 1942 in Marseille | Returned to Soviet Union, sent to Lubyanka prison, later deported to labour camp. Rehabilitated in 1990. | Leader of the Gurevich Group. Real name Anatoly Gurevich. Codenames: Kent, Fritz, Arthus Barcza, Simon Urwith, Manolo, Dupuis, Lebrun); see name Table. G. Founded the Simexco company as a cover for intelligence work in Brussels in autumn 1940. Gurevich and Nazarin Drailly were principal stockholders and managing directors.[111][112] | |

H[edit]

| People of the Red Orchestra | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Life | Employment | Rote Kapelle or military position | Group | Arrested | Fate | Notes | |

| Max Habjanic | Swiss bureaucrat of Balkan descent | Provider of fake identity papers | Rote Drei |

Survived the war |

Code name:Cobbler Max. Provided passports for Anna Barbara Müller that eventually reached Henry Robinson. Habjanic used blank forms to create passports and then sent individual copies of each form to various senior police officers who signed them without suspecting what they were.[113] | |||

| Ruthild Hahne | (1910–2001) | Sculptor | Communist. House used as a meeting place. Worked on the Die Innere Front (The Internal Front) | Harnack and Schulze-Boysen Groups | Arrested on 21 August 1943. The 2nd Senate of the People's Court sentenced her on 21 August 1943 to four years in prison. In February 1945, Hahne was able to escape from the women's prison in Cottbus | Survived the war | Became involved with Harnack through Fritz Cremer, Cay von Brockdorff, and Wolfgang Thiess. Moved to East Germany after the war and joined the Socialist Unity Party of Germany.[114] | |

| Rudolf Hamburger | (1903–1980) | Architect | GRU, Red Army intelligence agent, Undertaking photographic jobs | Rote Drei | Survived the war | Codename Rudi. First husband of Ursula Kuczynski, who was Sonia directing Swiss groups.[115] | ||

| Edmond Hamel | (1910–?) | Trained as a wireless specialist | Trained by Alexander Foote on WT operations and began transmitting to Moscow in March 1941 | Rote Drei | 8 October 1943. Served only five days as Swiss did not know his true identity. | Released July 1944. Sentenced in 1947 and imprisoned for nine months. Survived the war. |

Husband of Olga Hamel.[116] | |

| Olga Hamel | (1907–?) | Trained as a wireless specialist | Assisted her husband in the transmission of WT traffic. | Rote Drei | 8 October 1943 | Released July 1944. Later sentenced to 7 months in 1947 by a Swiss court. | Code name: Delez, Maud. Wife of Edmond Hamel. When arrested, 129 messages were found in their flat. Received large sums of money from Alexander Radó in 1942 and 1942[117] | |

| Ernst Happach | Ran a duplicating machine in his apartment to duplicate AGIS leaflets created in part by John Graudenz | Shulze-Boysen Group | Arrested in Berlin on 12 September 1942 | Spend two years in prison for "failure to report a plan of high treason". | Recruited by Libertas Schulze-Boysen | |||

| Arvid Harnack | (1901–1942) | Jurist, economist | Scientific expert in the Reich Economic Ministry | Formed the Harnack Group | Arrested on 7 September 1942. | The 3rd senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced the death penalty on 19 December 1942. Hanged four days later at Plötzensee Prison. | [118] | |

| Falk Harnack | (1913–1991) | Director and screenwriter | Leafletting | Harnack Group, later joined White Rose | Arrested and acquitted on 19 April 1943. In August 1943 he was removed from Wehrmacht and transferred to a penal battalion, the 999th Light Afrika Division. In December 1943 sent to a concentration camp but escaped. | Survived the war in Greece | Brother to Arvid Harnack.[119] | |

| Mildred Harnack | (1902–1943) | Literary historian and translator | Brought together a discussion circle at home that created the Red Orchestra | Harnack Group | Arrested on 7 September with her husband Arvid Harnack, when a radio message they had sent was read by Referat 12 | Initially given six years in prison, but Hitler ordered a new trial and she was sentenced to death on 16 January 1943 by the 3rd senate of the Reichskriegsgericht. She was executed on the same day. | Mildred Harnack is the only member of the Red Orchestra whose burial site is known.[120] | |

| Hilde Hauck | (1905–1988) | Administrator and interpreter | KPD | Survived the war | Under the supervision of the Gestapo for the duration of the War. | |||

| Hans Hausamann | (1897–1974) | Swiss author and intelligence officer | Provided information to Czech Colonel Karel Sedlacek | Directed Büro Ha, the unofficial autonomous Swiss intelligence centre, loosely attached to official Swiss military intelligence. | Survived the war | [121] | ||

| Robert Havemann | (1910–1982) | Chemist and later East German dissident | KPD, founded the European Union resistance group | Arrested in 1943. | Fate was postponed several times until the Brandenburg-Görden Prison was liberated by the Red Army. Survived the war | [122] | ||

| Wolfgang Havemann | (1910–1982) | Lawyer | Communist | Harnack Group | Arrested on 5 September 1943 by Gestapo. The 2nd senate of the Reichskriegsgericht condemned him on 17 February 1943 for failed high treason to nine months in prison | Survived the war | Son of Gustav Havemann, who was a prominent Nazi. Created the European Union Resistance Group. On 16 December 1943 sentenced to death by the People's Court and later had the sentence deferred several times by Wolfgang Wirth, a senior scientist from the Waffenamt.[123] | |

| Horst Heilmann | (1923–1942) | Student and wireless operator. Cryptanalyst | Passed secret communications from the Abwehr to the Group. Later tried to warn Shulze-Boysen when the GRU spy Johann Wenzel's traffic was deciphered by Referat 12 and Schulze-Boysen was exposed. | Schulze-Boysen Group | On 19 December 1942, the 3rd senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced the death penalty | On 22 December 1942, executed by decapitation at Plötzensee Prison. Executed with Harro Schulze-Boysen. | Recruited by Schulze-Boysen.[124] | |

| Carl Helfrich | (1906–1960) | Journalist | Worked in the Foreign Office, where Rudolf von Scheliha was Head of Unit | Harnack and Schulze-Boysen Groups | Sent directly to a concentration camp | Survived the war | [125] | |

| Bruno Hempel | Leafleting and pamphleting | Schulze-Boysen Group | Arrested in spring 1943 | 2nd Senate of the People's Court condemned him on 21 August 1943 to two years in prison. | Had contact with Wilhelm Schürmann-Horster | |||

| Hans Henniger | (1904–?) | Luftwaffe inspector, later soldier | Allowed John Graudenz to elicit information from him. | Schulze-Boysen Group | Arrested on 9 October 1942 in Berlin | the 2nd Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced on 20 January 1943 "for disobedience in the field and surrendering a state secret", and sentenced to four years. | [126] | |

| Rudolf Herrnstadt | (1903–1966) | Journalist | Communist politician and Soviet agent | Von Scheliha Group | Survived the war | During World War II, he held a senior position in the Red Army.[127] | ||

| Kurt Hess | (1901–?) | Dentist | Let John Sieg use his dentist's office to host illegal meetings. Communist. | |||||

| Henrika Hillbolling | Courier | Winterink Group | Arrested on 19 August 1942 in Amsterdam. | Sent to Fort Breendonk prison. Executed in January 1943. |

Her husband, Jacob Hillbolling, was executed at the same time as Henrika. | |||

| Jacob Hillbolling | Scout and Courier | Winterink Group | Sent to Fort Breendonk prison. Executed in January 1943. | His wife, Henrika Hillbolling, was executed at the same time as Jacob. | ||||

| Helmut Himpel | (1907–1943) | Electrical engineer, later became a dentist | Treated Jewish patients free of charge. Distribution of pamphlets. Distributed the teachings of Galen, which cited the Aktion T4 that resulted in Hitler stopping the killing of mentally ill patients. | Through John Graudenz met Schulze-Boysen Group | Arrested on 17 September 1942 in Berlin. | The 2nd Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht Reichskriegsgericht announced on the 26 January 1943 the death penalty citing "preparation for high treason and enemy favoritism". | One of the core group around Schulze-Boysen and fiancé of Maria Terwiel.[128][129] | |

| Albert Hoessler | (1910–1942?) | Labourer | KPD member, Communist, Soviet intelligence agent | Murdered September 1942 without trial | Codename Stein, Franz.[130] On 5 August 1942 parachuted into Germany. Sent to establish a WT link to Moscow for the Schulze-Boysen Group, initially from Erika von Brockdorff's apartment and then from Oda Schottmüller apartment. | |||

| Walter Hoffmann | Toolmaker | Took part in discussion groups, listened to foreign broadcasts and distributed leaflets. | Schulze-Boysen Group | The 2nd Senate of the People's Court sentenced him to one year in prison on 21 August 1943 | Personal friend of Harro and Libertas Schulze-Boysen. | |||

| Karl Hofmaier | (1897–1988) | Journalist | Expelled from the Swiss Communist Party. Joined the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland. | Rote Drei Group | Survived the war | Close to Alexander Radó and Rachel Dübendorfer.[130] | ||

| Walter Homann | (1906–1945) | Locksmith and metal worker | KPD. Worked at the AEG turbine factory helping his colleagues, who were killed at the same time as him. | AEG turbine factory Group | Arrested 8 February 1945. | Sentenced on 21 March 1945 and murdered on the same day at Plötzensee Prison. | ||

| Margarete Hoffmann-Scholz | Trepper Group via the small Basile Maximovitch Group | Sentenced to six years in prison | Niece of the commander of Paris, General Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel. | |||||

| Caroline Hoorickx | Assisted the Belgian network from 1939 to 1941. Courier for Gurevich. | Gurevich Group | Wife of Guillaume Hoorickx. Mistress of Anton Makarov.[131] | |||||

| Guillaume Hoorickx | (1900–?) | Painter | Agent of the Gurevich Group in Belgium between 1940-1942. Used own apartments for meetings. In early 1942, moved to Simexco to work as a buyer but really as a courier. | Gurevich Group and the Trepper Group | Arrested on 28 December 1942. Repatriated to Belgium on 2 June 1945. | After the war tried to contact former Simexco people. | Codename Bill.[132] | |

| Arthur Hübner | (1899–1962) | During interwar period sent on missions to Europe for the General Staff of the Red Army. Acted as a Scout | Survived the war | Precursor to the Red Orchestra. Many of Hübner's family were involved the Schulze-Boysen and Harnack groups. His father was Emil Hübner.[133] | ||||

| Emil Hübner | (1862–1943) | Politician | Worked for Communist International from the 1920s. Arranged accommodation including his own house for Soviet parachutists. | Arrested September 1942 | 2nd Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced on 10 February 1943 the death penalty. Executed on 5 August 1943 at Plötzensee Prison. | Whole family including grandchildren were arrested and executed. Frida Wesolek was his daughter. | ||

| Max Hübner | (1862–1943) | German politician | KPD, worked with the Communist International. Trained as radio operator. Ran a photography shop in his basement to create false documents including passports, set up with KPD money. The unit also built radio transceivers. | Shulze-Boysen Group | Arrested on 18 October 1942 in Berlin. | Death penalty on 10 February 1943 "for aiding and abetting the preparation of a highly treacherous enterprise and espionage". | Worked with Adam Kuckhoff, Wilhelm Guddorf and John Sieg.[126] | |

| Marie Hübner | (1903–2001) | Domestic servant | Shulze-Boysen Group | Survived the war. | Became friends with Erika von Brockdorff. Married Wilhelm Hübner.[134] | |||

| Jules Humbert-Droz | (1872–1971) | Swiss journalist and pastor. | Thought to be an agent of Maria Josefovna Poliakova before the war. Later recruited agents for Alexander Radó. | Rote Drei | Arrested June 1942 and expelled from Switzerland | Known to have survived the war | Established Comintern Youth International in Switzerland with Willi Münzenberg and Henry Robinson.[135] | |

| Arlette Humbert-Laroche | (1915–1945) | French poet and secretary at an unemployed workers' organisation | Distributing leaflets to factories. | Travelled between several groups | Arrested January 1943 | She was locked up in Fresnes Prison, then deported to Germany where she was sent to Ravensbrück camp, then to Mauthausen and later Bergen-Belsen concentration camp | [136] | |

| Charlotte Hundt | (1900–1943) | Clerk | Hosted the parachutist Ernst Beuthke at her house. | Arrested on 17 May 1943 in Wittenau | Executed on 11 August 1943 in the industrial house of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp | Friends of the Ernst Beuthke family. Killed on the same day as Dora Baumann, Anna Becker, Anna Beuthke, Charlotte Beuthke, Lina Mueller, Wally Radoch and Ella Trebe, one day after their husbands.[137] | ||

| Marta Husemann | (1913–1960) | Actress | Communist. KPD member. | Schulze-Boysen Group | In November 1936 and the following March to June 1937 detained at the Moringen concentration camp. 2nd Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht sentenced her on 26 January 1943 for preparing a highly treasonous company to a 4 years of imprisonment. Captured in 1945 by the Red Army. | Survived the war | Husband of Walter Husemann. | |

| Walter Husemann | (1909–1943) | Editor | Communist. Worked for the NKGB | Schulze-Boysen Group | On 9 September 1942, Husemann was arrested at this workplace. Sentenced to death on January 26, 1943, for "Preparation to high treason and aid for espionage" and executed at Plötzensee Prison | 2nd Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced on 26 January 1943 for preparation for treason and aiding espionage. Executed on 13 May 1943 | Codename Akim. Taught Hans Coppi the radio in 1941.[138] | |

I[edit]

| People of the Red Orchestra | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Life | Employment | Rote Kapelle or military position | Group | Arrested | Fate | Notes | |

| Else Imme | (1885–1943) | Retail manager | Collected monies for persecuted fellow citizens. Distributed Soviet radio transmissions. Held illegal meetings in her apartment for the Schulze-Boysen group | Schulze-Boysen Group | Arrested 18 October 1942. On 30 January 1943, 2nd Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht sentenced her to death for favoring the enemy | 5 August 1943 executed at Plötzensee Prison | ||

| Hermann Isbutzki | (1914–1944) | Radio operator who was to build his own network | Gurevich Group then Trepper Group and later Jeffremov Group | Arrested on August 13, 1942 in Brussels | Executed in July 1944 in Plötzensee Prison. | Arrested when Jefremov, who was under German control betrayed him, and tortured for almost a year. Heinz Pannwitz used his name to conduct playbacks, i.e. maintaining the connection to Moscow.[139][140] | ||

J[edit]

| People of the Red Orchestra | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Life | Employment | Rote Kapelle or military position | Group | Arrested | Fate | Notes | |

| Franz Jacob | (1906–1944) | Machine fitter | Built the Saefkow-Jacob-Bästlein Group | Saefkow-Jacob-Bästlein Group | 4 July 1944 | On 5 September 1944 sentenced to death by the People's Court and executed on 18 September 1944, at Brandenburg-Görden Prison | [141] | |

| Krystana Iwanowa Janewa | (1914–1944) | Soviet agent | Shulze-Boysen, Harnack and Bästlein Groups | Arrested in late 1944. Taken to the Barnimstrasse women's prison in Berlin and later transferred to a prison in Halle | Janewa died from ill treatment | [142] | ||

| Jean Baptiste Janssens | (1898–?) | Shoemaker | Courier | Jeffremov Group | Arrested January 1943 | Janssens died in Breendonk concentration camp | [143] | |

| Jules Jaspar | (1878–1963) | Belgian Consul | Director of Foreign Excellent Raincoat Company. Helped people persecuted by the Nazis. | Trepper Group | Arrested and sent to Mauthausem concentration camp | Liberated in May 1945. Survived the war | In 1942, helped establish Simexco in Marseille.[143] | |

| Konstantin Jeffremov | (1910–?) | Soviet Army Captain, engineer and chemical warfare expert | Soviet agent | Worked all over Europe, later built Jeffremov Group in Belgium | Arrested on 22 July 1942 and conducted a playback in Fort Breendonk until late November 1944 | Unknown | Agent active in Europe from 1936.[144] | |

K[edit]

| People of the Red Orchestra | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Life | Employment | Rote Kapelle or military position | Group | Arrested | Fate | Notes | |

| Ludwig Kainz | Construction engineer in Organisation Todt | December 1942 in Paris | Sentenced to three years in prison | |||||

| David Kamy | (1911–1943) | Graduate Chemist | Radio operator who was trained by Johann Wenzel alongside Sophia Poznańska. | Gurevich Group | 13 December 1941 | Assumed to be Anton Danilov while undercover. Captured at 101 Rue des Atrebates, Brussels[145] | ||

| Louis Kapelowitz | (1891–19??) | Czech commercial director | Director of the Excellent Raincoat Company and later director of the subsidiary, the Foreign Excellent Raincoat Company | Trepper Group | Survived the war | Kapelowitz's wife, Sarah, was the sister of Leon Grossvogel. Maurice Padawer and Adolf Lerner, directors of the Foreign Excellent Raincoat Company, were both married to sisters of Louis Kapelowitz.[146] | ||

| Hillel Katz | (1905–1943) | Secretary at Simex company | Trepper Group | December 1942 when the Simex people were rounded up. | Disappeared in November 1943. Likely shot without trial | Code names:Andre Dubois, Rene and Le Petit Andre. Assistant to Trepper who betrayed him. He was responsible for liaison between Leon Grossvogel, Henry Robinson and the Simex company.

| ||

| Gerhard Kegel | (1907–1989) | Diplomat | KPD member | Von Scheliha Group | Survived the war. | According to Simon Wiesenthal, Kegel worked for the Gestapo during World War II.[148] | ||

| Waldemar Heinrich Keller | (1906–1991) | Simex technical advisor | Trepper Group | Arrested on 19 November 1942 in Paris | Sentenced to three years in prison | Made a fortune before his arrest by dealing in industrial diamonds with the Todt Organization. Seemed to be an agent who worked mainly for money.[149] | ||

| Helmut Kindler | (1912–2008) | Journalist | European Union Group | Had a successful career after the war. | Kindler was a childhood friend of Ilse Stöbe. | |||

| Richard Klotzbücher | (1902–1945) | Cashier and HR person at AEG Turbine Factory | Suppression of Nazi state efforts | Saefkow-Jacob-Bästlein Organization | Arrested on 22 February 1945 | Executed on 10 April 1945 in Plötzensee Prison for "preparation of treason" | [150] | |

| Heinrich Koenen | (1910–1945) | German engineer | Soviet agent | Von Scheliha Group | Arrested on 29 October 1942 | Executed without trial at Sachsenhausen concentration camp in February 1945 | Parachutist. Parachuted into Germany on 23 October 1942 to receive some intelligence from Rudolf von Scheliha and blackmail him if the intelligence was not forthcoming but was arrested within several days.[151] | |

| Aleksandr Mikhaylovich Korotkov | (1909–1961) | Soviet Agent | Recruited Arvid Harnack around December 1941. | Survived the war | 1941 Deputy Resident of the NKVD in Berlin. Code name was Alexander Erdberg. Erdberg acted as a contact between Moscow and the Harnack and Schulze-Boysen groups in Berlin. Later from 1946 to 1957 Korotkov was deputy Head of foreign intelligence service of the KGB of the USSR[152][153] | |||

| Anna Krauss | (1884–1943) | Lacquer and paint wholesaler | Fortune-teller and clairvoyant who counted Libertas Schulze-Boysen as a client. She used her apartment to create and print leaflets and pamphlets with John Graudenz | Schulze-Boysen Group | September 14, 1942 in Berlin | 2nd Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced on 12 February 1943 the death penalty for decomposing the military force | Read the fortunes of all the Schulze-Boysen group to provide and engender a steely backbone for the group.[154] | |

| Werner Krauss | (1900–1976) | German Romanist academic | KPD Communist. | Schulze-Boysen Group | 24 November 1942 in Berlin | 2nd Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced the death penalty on 18 January 1943, the sentence was revised on 14 September 1944 to five years in prison. Survived the war | Made contact with Shulze-Boysen via John Rittmeister and supported their actions on many occasions.[155] Krauss wrote an anti-fascist novel Die Passionen der halykonischen Seele in 1943.[156] His sentence was commuted from the death penalty to a period in jail after a plea of clemency from his academic friends at the University of Marburg where he was employed.[157] | |

| Willy Kruyt (John W. Kruyt Sr.) | (1877–1943) | Dutch Protestant minister | Soviet agent, Parachutist | Jeffremov Group | 20 July 1942 | Successively jailed in St Gilles, Breedonck, and Moabit prisons. Believed to have been executed at Moabit in 1943. | Sent by Soviet intelligence to provide a bastion for the Jeffremov Group[158] | |

| John W. Kruyt Jr. | (1926–?) | Soviet agent, Parachutist | Dropped in the Netherlands to supply a radio to Daan Goulooze. Son of John W. Kruyt Sr.[158] | |||||

| Walter Küchenmeister | (1897–1943) | German machine technician, communist, political writer | Wrote a number of pamphlets | Schulze-Boysen Group | Arrested on 16 September 1942 | On 6 February 1943, he was sentenced to death by the 2nd Senate of the Imperial War Court for belonging to the resistance organisation. Executed on 13 May 1943 in Plötzensee Prison. | [159] | |

| Adam Kuckhoff | (1887–1943) | German writer, journalist who wrote on communist and marxist philosophies | Produced and collaborated on illegal pamphlets. Also worked on writing the Die Innere Front (The Inner Front) | Harnack Group | 12 September 1942, arrested in Prague. The 2nd Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced the death penalty on 6 February 1943 for preparing a highly treasonous company and for Enemy favorability | 5 August 1943, executed at Plötzensee Prison | Also closely affiliated with the Shulze-Boysen Group and considered an important member of both groups. His wife was Greta Kuckhoff.[158][160] | |

| Margarete Kuckhoff | (1902–1981) | Economist | Harnack Group | Arrested on 12 September 1942, the same day as her husband. | On 3 February 1943, she was sentenced to death as an accomplice to high treason and [for] failure to report a case of espionage by the 2nd Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht. However her sentence was lifted on 4 May 1943, but a second trial on 27 September 1943 resulted in a sentence of ten years at Waldheim Prison where she was liberated by the Red Army in May 1945. Survived the war | Known by the first name as Greta. Husband was Adam Kuckhoff. Important member of the Harnack Group as well.[161][162] | ||

| Ursula Kuczynski | (1907–2000) | Editor | Soviet agent. | Survived the war | Code name: Ruth Werner, Ursula Beurton, and Ursula Hamburger.[163] Sent to Switzerland during the interwar period to build an intelligence network. Later she became a handler of Klaus Fuchs, couriering intelligence to the Soviet Union from 1943. Considered one of the top Soviet spy's during the post-war period.[164] KPD member. | |||

| Yvonne Kuenstlunger | Cutout | Trepper Group | Cousin of Rita Arnould. Managed the contacts between Rue des Atrébates and Isidor Springer.[165][166] | |||||

| Hans-Heinrich Kummerow | (1903–1944) | Telecommunications engineer and designer at the Opta Radio AG in Berlin | Supplied intelligence to the Soviet Union | Arrested in Berlin at the end of November 1942 | 3rd senate of the Reichskriegsgericht announced on 18 December 1942 the death penalty for high treason. Beheaded in Halle Prison on 4 February 1944. | Husband of Ingeborg Kummerow.[167] Occasionally used Schulze-Boysen's groups radio transmitter to transmit reports to Moscow. | ||

| Ingeborg Kummerow | (1912–1943) | Arrested in September 1942. On January 27, 1943, she was sentenced to death for aiding and abetting espionage by the 4th Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht. | On 5 August 1943, she was executed in Plötzensee Prison | Wife of Hansheinrich Kummerow.[167] | ||||

| Hans Kurfess | (1915–?) | Lawyer | German cryptanalyst worked in Referat 12 | Later enciphered texts prepared by Anatoly Gurevich as part of Sonderkommando Pannwitz in Paris.[168][169] | ||||

L[edit]

| People of the Red Orchestra | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Life | Employment | Rote Kapelle or military position | Group | Arrested | Fate | Notes | |

| François Lachenal | (1918–1997) | Swiss publisher and diplomat | Informant | Rote Drei | Code name: Diener. Passed low grade intelligence to Jean-Pierre Vigier, the son in law of Rachel Dübendorfer.[170] | |||

| Otto Lang | (1890–1945) | Office worker. Also employed as an umbrella maker. | SPD | Working in AEG factory, spreads foreign news and leaflets. Support families who have been persecuted by the Nazi's. | Arrested in February 1945 | On 10 April 1945, murdered in Plötzensee Prison | [171] | |

| Fritz Lange | (1898–1981) | Teacher and soldier | Co-editor of the Die Innere Front (The Inner Front) | Bernhard Bästlein and Wilhelm Guddorf | On 8 October 1943 the 2nd Senate of Reichskriegsgericht sentenced him to five years in prison "for aiding the high treason and enemy favoritism" | Survived the war | Member of the Harnack Group through Wilhelm Guddorf. | |

| Hans Lautenschläger | Commercial employee and union official | Schulze-Boysen group | Arrested on 24 February 1943 on Guernsey |

The 2nd Senate of the Reichskriegsgericht on 3 July 1943 for decomposition of the military force and preparation for high treason. The death penalty was never carried out. |

Married Ina Ender on 14 September 1936. He and his wife, Ina, appeared as themselves in a 1988 titular documentary-style film directed by Thomas Grimm.[172][173] | |||

| Claire Legrand | (?–1944) | Trepper Group | Arrested on 30 November 1942 in Marseille by the Gestapo | In November 1944 sent to Auschwitz concentration camp and executed. | Wife of Jules Jaspar.[174] | |||

| Willy Lehmann | (1884–1942) | Police officer, Gestapo | Soviet Agent | Worked in the Office IV of the Reich Security Main Office | December 1942 discovered | Shot without a trial | [175] | |

| Ernst Lemmer | (1898–1970) | German journalist, later politician | Informant for Georges Blun | Rote Drei | Survived the war. | Code name: Agnes.[9] | ||

| Waldemar Lentz | (1909-?) | German cryptanalyst worked in Referat 12 and part of Sonderkommando Pannwitz in Paris | Arrested on 5 September 1942 in Berlin and later released. | Survived the war | Members of Referat 12 detached to Aussenstelle Paris.[176][177] | |||

| Friedrich Lenz | (1885–1968) | Professor of economics | Liaison between intelligence groups and the Soviet embassy. cutout between Harnack and the Soviet embassy in 1941. | Harnack Group and others | Survived the war and went back into academia. | His Soviet principal was Gunther Lubszynski.[178] | ||

| Abraham Isaac Lerner | (1891–?) | Commercial director | Director of the Foreign Excellent Raincoat Company | Trepper Group | Managed to escape arrest in May 1941 and moved to New York via Portugal | Code name: Adolf.[179] | ||

| Antonia Lyon-Smith | (1925–2010) | Schoolchild | Betrayed the French resistance. | 21 October 1943 by Heinz Pannwitz. | Went on to live a happy life in Devon.[180] | Acquainted with Claude Spaak who procured false papers for her. Unwittingly assisted the escape of Leopold Trepper. Daughter of British Brigadier Tristram Lyon-Smith. She became linked to Gestapo agent, Karl Gagl, a member of Sonderkommando Pannwitz, who wanted to marry her but didn't.[180][181] | ||

| Wilhelm Leist | (1899–1945) | Toolmaker | KPD | Founded a resistance group at the AEG turbine factory | Arrested on 7 March 1945 by the Gestapo | Murdered on 10 April 1945 at Plötzensee Prison | [182] | |

| Hans Gerhardt Lubszynski | (1904–?) | German research and radio engineer, member of the German Communist Party. | Informant | Trepper Group | Identified in the Robinson papers an agent. Worked with Heinz Erwin Kallmann in England who identified with the code name of Professor.[179] | |||

| Rose Luschinsky | (1903–?) | Physician | Trepper Group | Sister of Rachel Dübendorfer. Identified in the Robinson papers an agent under the code name: Jenny.[179] | ||||

M[edit]

| People of the Red Orchestra | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Life | Employment | Rote Kapelle or military position | Group | Arrested | Fate | Notes | |

| Mikhail Makarov | (1915–circa 1942) | Soviet intelligence agent | Ran the Foreign Excellent Raincoat Company. Was an expert in false documents and secret inks. | Trepper Group |

Executed in Plötzensee Prison circa 1942. |

Code name Carlos Alamo, Chemnitz. Offered wireless telegraphy training to people recruited by Trepper.[183] | ||

| Helmut Marquardt | Assistant radio operator | Shulze-Boysen Group | Acquittal in a trial of the 2nd senate of the Reichskriegsgericht on 3 July 1943 | After his acquittal the 19-year-old Marquart received a protective detention order and was admitted to Sachsenhausen concentration camp.[184] | ||||

| Charles Mathieu | Inspector in Belgian Gendarmerie | On behalf of the Gestapo, penetrated the Rote Kapelle in Belgium, leading to the arrest of Jeffremov.[185] | ||||||

| Anna Maximovitch | (1901–1943) | Neurologist | Ran the 4th Trepper sub-network | Trepper Group | December 1942 | 20 July 1943 in Plötzensee Prison | Code name: Arztin. Provided intelligence from French clerical and royalist sources including Bishop Chaptal of Paris.[186] | |

| Basile Maximovitch | (1902–1943) | Chemist and Civil-Mining engineer | Ran the 3rd Trepper sub-network | Trepper Group | 16 December 1942 | 6 July 1943 at Plötzensee Prison | Code name: Professor. Provided intelligence from white Russian emigrant groups; also from German Wehrmacht personnel. In a relationship with Margarete Hoffmann-Scholz. Brother of Anna Maximovitch.[186] | |

| Bernhard Mayr von Baldegg | (1909–1980) | Swiss intelligence office | Reported to Captain Max Waibel.[187] | |||||

| Marcel Melliand | (?–1943) | Businessman and publisher of textile magazine | Courier. Schulze-Boysen used John Graudenz to pass information to England via Melliand but Melliand was unable to get a visa.[188] | Schulze-Boysen Group | 26 September 1942 in Heidelberg | Had excellent business contacts in Switzerland and was considered a strong anti-fascist.[188][189] | ||

| Franz Mett | (1904–1944) | Miner and metal worker | Built resistance group centred around Robert Uhrig and was in contact with the resistance in Berlin | Uhrig group | 4 February 1942 | Sentenced to death on 7 June 1944 and executed on 21 August 1944 in Brandenburg-Görden Prison. | [190] | |

| Ewald Meyer | (1911–2003) | Artist and graphic artist | Illustrated a number of banned book by Nazi's that were used to resist. Also helped illustrate leaflets | Survived the war | After the war his career flourished and he had a large number of exhibition in different European countries. | |||

| Wilhelm Milke | (1896–1944) | Metalworker | KPD member, Communist | Bästlein-Jacob-Abshagen Group | Arrested on 21 October 1942 | Milke was found dead in his cell in Plötzensee Prison | Helped to organise aid for those of were persecuted and supported foreign forced labour.[191] | |

| Juliette Moussier | (1892–?) | Employee of the Confiserie Jacquin, a confectionery manufacturer | PCF member, Courier | Trepper Group | Passed reports from the Trepper Group to the French Communist Party.[192] Later Trepper requested a meeting with Moussier as part of a German playback operation, while he was in custody to prove to Soviet intelligence that he was still free and enable the playback operation to continue, otherwise he would likely have been executed. Instead he managed to pass a long message containing the news that we was exposed along with a large number of people who were captured. Trepper requested that Moscow send a radio message to the Sonderkommando Rote Kapelle from the Red Army to indicate that they understood.[193] | |||

| Marius Mouttet | (1876–1968) | French minister, later socialist diplomat and colonial adviser | Informer to Foote | Rote Drei | Did not appear in Rote Drei traffic after 1942.[185] | |||

| Anna Barbara Müller | (1880–?) | Seamstress, later owned an appointments agency | Soviet agent | Arrested in June 1943 in Freiburg after being enticed in Germany to help her brother. | Sentenced to death but the Swiss intervened and was given 2 year sentenced. Released by the Soviets. | Code name:Anna (Not the Rote Drei Anna in the German Foreign Office). In 1936 worked for Maria Josefovna Poliakova. Kept in custody during the Robinson interrogation.[185] | ||

| Karl Müller | (1904–1945) | German Locksmith who worked at the AEG turbine factory in Berlin | KPD member. | Uhrig Group | February 24, 1945 when he was tortured by the Gestapo | Committed suicide on March 21, 1945 by hanging himself. | [194] | |

| Lina Müller | (1901–1943) | Communist | 21 April 1943 | Shot dead without trial in Sachsenhausen concentration camp | Husband was Heinrich Müller. Friend of the Ernst Beuthke family. Killed on the same day as Dora Baumann, Anna Becker, Anna Beuthke, Charlotte Beuthke, Charlotte Hundt, Wally Radoch and Ella Trebe on 11 August 1943. | |||

| Kurt Müller | (1903–1944) | German carpenter and communist | Prepared and distributed pamphlets. | Part of the resistance group European Union. | Kurt Müller was a half brother of Ilse Stöbe. Also prepared documents to move Jews out of trouble. | |||

| Hans Mussig | (1904–?) | French intelligence agent from February 1939 | Arrested in Grenoble by the Gestapo | Tortured 35 times by the Gestapo until he agreed to work with the Sonderkommando Pannwitz. | Code name: Jean Varon, Rueff. Married to Ilse Bach. Helped to penetrate French resistance.[195] | |||

N[edit]

| People of the Red Orchestra | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Life | Employment | Rote Kapelle or military position | Group | Arrested | Fate | Notes | |