List of species in the Port Kennedy Bone Cave

A list of prehistoric and extinct species whose fossils have been found in Port Kennedy Bone Cave, located within the limits of Valley Forge National Historical Park, located in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, US.

Most of the fossils excavated from the site are deposited within the collections of the Academy of Natural Sciences Philadelphia, including those unearthed by both the crews of anthropologist Henry Mercer (1895–96) and paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope. Daggers denote extinct species.

Mammals[edit]

Artiodactyla[edit]

| Common name | Species | Material | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| † Long-nosed peccary[1][2][3] | †Mylohyus nasutus | One of two fossil peccaries known from Irvingtonian North America. Several fossils were referred to a new species named Mylohyus tetragonus by Edward Drinker Cope in 1899.[3] Fossils were also assigned to M. pennsylvanicus as well,[3] but all have been assigned to M. nasutus.[1] |  | |

| † Teleopternus orientalis[3] | Four molars.[4] | A species known from only a single specimen originally described by Cope in 1899.[3] The teeth are large, with Cope estimating it to be about the size of an elk.[3][1] The phylogenetic placement of the species has been stated to be cervid or camelid.[5][1] | ||

| White-tailed deer[5][1] | Odocoileus virginianus | Several specimens. | An extant species of deer, originally described from the site as a new species of mule deer, Cariacus laevicornis, by Cope (1896).[6] C. laevicornis was named based on several teeth and two partial antlers.[4][6] |  |

Carnivora[edit]

| Common name | Species | Material | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American badger[7] | Taxidea taxus | Fossils of badgers are uncommon, making up little of the carnivoran fossils compared to canids and felids.[1] First referred to Taxidea americana, a synonym of T. taxus.[3] |  | |

| American black bear[1][2][8] | Ursus americanus | Port Kennedy features the earliest known fossils of black bears, with Cope mentioning their presence in 1895.[2][1] Black bears are medium-sized and omnivorous, though smaller than Arctodus pristinus.[8] |  | |

| † Miracinonyx inexpectata[9] | A relative of the cougar which convergently evolved several cheetah-like characteristics built for running. It too was carnivorous and medium-sized, around 70 kg (150 lbs).[10] Fossils are known from much of the United States, including very mountainous regions such as the Grand Canyon, implying they may have had high-altitude adaptations. |  | ||

| American river otter[7] | Lutra canadensis | A single partial mandible and teeth.[6] | The North American river otter is a medium-sized, semiaquatic carnivore endemic to eastern North America. The oldest fossils of American river otters come from Port Kennedy and Cumberland Cave.[11][1] Cope considered the Port Kennedy specimen distinct, dubbing it L. rhoadsii, but it has been lumped with L. canadensis.[12][1] |  |

| †Canis armbrusteri[1] | Teeth and postcranial remains.[1] | A canid larger than the other Canis species, C. priscolotrans, known from only several large upper carnassials and postcranial remains.[1] The fossils have been assigned to the species C. ambrusteri, though is slightly smaller than respective fossils known from Cumberland Cave, Maryland.[1][13] Genetic data studied in 2021 found that the Rancholabrean species C. dirus actually belongs to the genus Aenocyon in a different lineage. This study implies that this species may be from the Aenocyon lineage.[14] |  | |

| Bobcat[1] | Lynx rufus | Mentioned by Cope (1895) as Lynx rufus,[2] but was referred to a new species, L. calcaratus, in 1899.[3] This species however is a synonym of L. rufus.[1][11] |  | |

| †Mustela diluviana[7][1] | A species of weasel unique to Port Kennedy, M. diluviana was named by Cope in 1899. However, Hay (1936) referred it to Martes,[7] though Daeschler, Spamer, & Paris (1993) kept it in Mustela.[1] | |||

| † Panthera onca augusta[1][15][16] | Very few specimens, a rare species from the site.[15] | A giant subspecies of the modern jaguar. The material was not mentioned until 1941 by George Gaylord Simpson.[1][15] |  | |

| Gray fox[3][2] | Urocyon cinereoargenteus | Port Kennedy has one of the first records of the gray fox, which were first described by Cope in 1895 as specimens of Vulpes cinereoargenteus.[2] Gray foxes are small and omnivorous, often eating hares and mice.[17][18] |  | |

| Jaguarundi[1] | Puma yagouaroundi | A single specimen. | The only fossil of a jaguarundi was initially assigned to Felis eyra,[2] but likely represent an early form of the jaguarundi.[11] |  |

| † Arctodus pristinus[8][1] | Many individuals, including several partial skulls and mandibles.[3] | Arctodus was one of the largest known carnivorans in history and belonged to the Tremarctinae, a subfamily of bears endemic to the Americas. Studies suggest that much like many modern bears, Arctodus was an omnivore with no direct adaptations for either hypercarnivory or scavenging as previously believed. This species is smaller than the later Arctodus simus, at only 133 kg (293 lbs).[19] |  | |

| †Osmotherium speleaum[7] | Many specimens.[7][1] | Osmotherium speleaum is endemic to Port Kennedy and very common, bearing the most specimens of any mustelid.[7] Cope (1899) described six species based on fragmentary material that are junior synonyms of O. speleaum.[1][11] | ||

| †Gulo schlosseri[1] | G. schlosseri is considered to be the ancestor of the extant Gulo gulo, with fossils exclusive to the Irvingtonian.[20][11][1] |  | ||

| †Brachyprotoma obtusata[7] | A partial mandible bearing three teeth. | Originally described as Mephitis obtustata by Cope (1899),[3] it was a strange species of skunk that lived as far north as Yukon Territory, Canada.[21] The holotype was lost for many years, until being rediscovered in 1993 and figured.[1] | ||

| † Smilodon gracilis[22][23] | Few fragmentary specimens, including a partial skull. | Smilodon is among the most well-known mammals from the Ice Age, but S. gracilis is far smaller than later species. S. gracilis was described on the basis of a canine from Port Kennedy by Cope in 1880 and was the ancestor to Rancholabrean species.[24][25] Unlike the American lion, which is a true cat, Smilodon was a member of the Machairodontinae. Based on the microwear texture of the teeth it has been suggested that Smilodon fed on both harder material and soft flesh, preferring the later following injuries to the jaws and teeth. |  | |

| † Canis edwardii[26] | Cope named a new species of Canis, C. priscolatrans, in his 1899 monograph on the fossils from the site. He named it on the basis of two molars and a premolar, the cotypes.[27][3] Several paratypes were also assigned, including a partial canine and phalanx, these specimens of considerable size.[27][3] The validity of C. priscolatrans was in question for decades, but the dimensions and anatomies of the teeth are not distinct from that of C. edwardii.[26][28] Tedford et al (2009) declared in a nomen dubium, but tentatively considered it a synonym of C. edwardii based on their similarities.[26] |  |

Edentata[edit]

| Common name | Species | Material | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

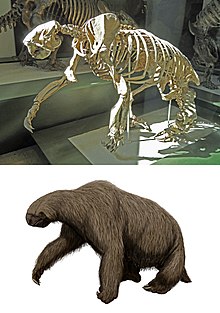

| †Wheatley's ground sloth[1] | †Megalonyx wheatleyi | Many specimens, including several partial skulls, mandibles, and associated remains. | Megalonyx wheatleyi is one of the most common species from Port Kennedy, with the site featuring one of the largest samples of the taxon. It was first named by Cope in 1871 along with 3 other Megalonyx species in his initial description of the site. The fossils he used were fragmentary, with the syntypes of M. wheatleyi consisting only of teeth. Cope named another species in 1899, M. scalper, but all species from the area have been synonymized with M. wheatleyi. |  |

Insectivora[edit]

| Common name | Species | Material | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-tailed shrew[1][3] | Blarina brevicauda | A single jaw in matrix. | Like with many other Port Kennedy mammals, Cope considered the material from the site to be of Blarina distinct, dubbing B. simplicidens in his 1899 monograph.[3] It has been recognized as a junior synonym of B. brevicauda.[29][1] |  |

Lagomorpha[edit]

| Common name | Species | Material | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern cottontail[1] | Sylvilagus floridanus | "a large number of individuals"[1] | Originally assigned to the hare species Lepus sylvaticus,[30] but it is considered a junior synonym of Sylvilagus floridanus.[1][11] |  |

| †Port Kennedy pika[1] | †Ochotona palatina | Teeth. | Cope described Praotherium palatinus based on several teeth in 1871,[30] but it was reassigned to the pika genus Ochotona in 1980.[11] However, its status is uncertain and has only fragmentary material.[1][11] |  |

Perissodactyla[edit]

| Common name | Species | Material | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| † Giant horse[1] | † Equus pectinatus | A large species of fossil horse, though the material has also been referred to the species E. giganteus, E. major, and E. fraternus.[3][1] However, the most recent assessment placed all specimens within E. pectinatus.[1] |  | |

| † Hays' tapir[1] | † Tapirus haysii | A large species of tapir known from the Irvingtonian sediments of eastern North America. Tapirs are typically semiaquatic herbivores with long proboscis at the front of their skull. T. haysii was named previously by Joseph Leidy in 1860[31] before a host of new fossils were described by Cope.[2][3] Later in 1945, George Gaylord Simpson referred all of the Port Kennedy fossils to a new species he dubbed T. copeii,[32] a junior synonym of T. haysii due to lack of sufficient distinguishing traits.[33][1] |

Proboscidea[edit]

| Common name | Species | Material | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| † American mastodon[34] | † Mammut americanum | Many fragmentary specimens, including juveniles. | The American mastodon is the only known proboscidean from Port Kennedy and the largest animal from the site.[30] It consumed a variety of wooded plants, being a mixed browser in forests.[35] |  |

Rodentia[edit]

| Common name | Species | Material | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| †Cope's muskrat[30][36] | †Ondatra hiatidens | Five specimens. | A fossil species of muskrat, a semiaquatic type of herbivorous rodent endemic to Port Kennedy. It was originally named by Cope (1871),[30] though he later named the junior synonyms of Arvicola hiatidens and Anaptogonia cloacina in 1871 and 1899 respectively.[37] Though it has been noted that species determination with fossils from the site is difficult due to the small pool of samples.[38][1] |  |

| †Diluvian water rat[1][36] | †Neofiber diluvianus | Cope named two species of microtines, Microtus diluvianus and Schistodelta sulcata, but only the former is valid.[6][3] M. diluvianus was moved to Neofiber by Hibbard (1955).[37] It was endemic to Port Kennedy, extant water rats being semiaquatic and nocturnal omnivores. |  | |

| Groundhog[1] | Marmota cf. monax | A partial humerus. | Not reported until it was described by Daeschler, Spamer, & Parris (1993).[1] |  |

| Meadow jumping mouse[3] | Zapus hudsonicus | A single partial mandible bearing one cheek tooth.[3] | Cope (1899) mentioned a specimen of Zapus hudsonicus, but it has been lost.[1][3] |  |

| North American porcupine[39][1][3] | Erethizon dorsatum | [40] |  | |

| North American beaver[1][3][2] | Castor canadensis | A single mandible and three isolated teeth.[3] |  | |

| †Squirrel[1][30] | †Sciurus calycinus | Two partial lower jaws. | Sciurus calycinus was dubbed by Cope in 1871,[30] but has been considered a synonym of the red squirrel, flying squirrel, or gray squirrel. There has not been an assessment, however.[1] |  |

| Voles[38] | Arvicolinae indet. | Vole fossils too fragmentary to be assigned on the specific level are known have been unearthed.[1] |  |

Insects[edit]

Only members of the family Coleopteridae have been reported from Port Kennedy, with chunks of clay containing fragments of beetles.[1][41] Several novel species of beetles from the site were described by George H. Horn in 1874 on the basis of eltyra and thoraxes, though they have all been lost.[41]

| Common name | Species | Material | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Ground beetles"[41][1] | †Cychrus wheatleyi, Cychrus sp. | C. wheatleyi is endemic to Port Kennedy. |  | |

| "Woodland ground beetles"[1][41] | Pterostichus sp. |  | ||

| †"Colorful foliage ground beetles"[41][1] | †Cymindis aurora | C. aurora is endemic to Port Kennedy. |  | |

| †"Vivid metallic ground beetles"[1][41] | †Chlaenius punctulatus | C. punctulatus is endemic to Port Kennedy. |  | |

| "Notch-mouthed ground beetles"[1][41] | †Dicaelus alutaceus, Dicaelus sp. | D. alutaceus is endemic to Port Kennedy. |  | |

| "Dung beetles"[1][41] | †Choeridium. (=Ateuchus) ebeninum, †Phaenaeus antiquum, †Aphodius precursor | All "dung beetles" described by Horn are endemic to Port Kennedy.[41] |  |

Birds[edit]

| Common name | Species | Material | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkey | Meleagrinae indet. | A single specimen. | The turkey fossils have been identified previously as Meleagris gallopavo, but differed from Meleagris in some respects.[42][1] |  |

Reptiles[edit]

| Common name | Species | Material | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern box turtle[43][1] | Terrepene carolina | Several specimens including carapaces and postcranial remains.[43] | Fossils had been referred to T. eurypygia by Hay (1908), but were reassigned to T. carolina by Parris & Daeschler (1995).[43] Many remains are assigned to cf. Terrapene sp., but likely belong to the same species.[43] |  |

| Blanding's turtle[43] | Emydoidea blandingii | A nearly complete plastron.[43] |  | |

| Eastern racer[1] | Coluber sp. | Vertebrae | The Coluber fossils from Port Kennedy have morphological similarities to Masticophis, but are more likely to be from the former due to their geography.[1] |  |

| †Tortoise[1][43] | †Geochelone (Hesperotestudo) percrassa | A carapace and plastron fragments.[43] | Geochelone was a large, herbivorous genus of tortoises that lived in the Americas until their extinction, possibly brought upon by human arrival.[43] The only fossils of G. percrassa come from the cave, though they were originally described as the species Clemmys percrassa by Cope in his 1899 monograph.[3] |  |

| Wood turtle[43] | Clemmys insculpta | A single fragmentary shell.[43] |  |

Plants[edit]

| Common name | Species | Material | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American beech[1][44] | Fagus grandifola |  | ||

| Pin oak[44][1] | Quercus palustris |  | ||

| White oak[1][44] | Quercus alba |  | ||

| Bur oak[44][1] | Quercus macrocarpa |  | ||

| American hazel[1][44] | Corylus americana |  | ||

| Pitch pine[1][44] | Pinus rigida |  | ||

| Cocksbur hawthorne or fireberry hawthorne[1][44] | Crataegus crus-galli or

C. chrysocarpa |

|||

| Hawthorne[44][1] | Crataegus sp. | Fossils of a hawthorne that cannot be identified at the specific level. |  | |

| Shagbark hickory[44] | Carya avata |  | ||

| Pignut hickory[44] | Carya glabra |  | ||

| Mockernut hickory[44] | Carya tamentosa |  | ||

| Virginia creeper[44] | Parthenocissus quinquefolia |  | ||

| Sphagnum moss[44] | Sphagnum sp. | Common on blocks of matrix.[1] |  |

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs Daeschler, E., Spamer, E. E., & Parris, D. C. (1993). Review and new data on the Port Kennedy local fauna and flora (Late Irvingtonian), Valley Forge National Historical Park, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. The Mosasaur, 5, 23–41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cope, Edw. D. (1895). "The Fossil Vertebrata from the Fissure at Port Kennedy, Pa". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 47: 446–450. ISSN 0097-3157. JSTOR 4061990.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Cope, Edward D. (1899) Vertebrate remains from Port Kennedy bone deposit. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 11:193–267.

- ^ a b Gillette, David D.; Colbert, Edwin H. (1976). "Catalogue of Type Specimens of Fossil Vertebrates Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia Part II: Terrestrial Mammals". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 128: 25–38. ISSN 0097-3157. JSTOR 4064716.

- ^ a b Hay, O. P. (1923). The Pleistocene of North America and its vertebrated animals from the states east of the Mississippi River and from the Canadian provinces east of longitude 95 (Vol. 322). Carnegie Institution of Washington.

- ^ a b c d Cope, E. D. (1896). "New and Little Known Mammalia from the Port Kennedy Bone Deposit". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 48: 378–394. ISSN 0097-3157. JSTOR 4062209.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hall, E. R. (1936). Mustelid Mammals from the Pleistocene of North America: With Systematic Notes on Some Recent Members of the Gerera Mustela, Taxidea and Mephitis.

- ^ a b c Kurtén, B. (1967). Pleistocene Bears of North America...: By Björn Kurtén.... Genus Arctodus, Short-faced Bears. Societas pro fauna et flora Fennica.

- ^ Van Valkenburgh, Blaire; Grady, Frederick; Kurtén, Björn (1990-12-20). "The Plio-Pleistocene cheetah-like cat Miracinonyx inexpectatus of North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 10 (4): 434–454. doi:10.1080/02724634.1990.10011827. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Barnett, Ross; Barnes, Ian; Phillips, Matthew J.; Martin, Larry D.; Harington, C. Richard; Leonard, Jennifer A.; Cooper, Alan (August 2005). "Evolution of the extinct Sabretooths and the American cheetah-like cat". Current Biology. 15 (15): R589–R590. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.052. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 16085477. S2CID 17665121.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Harris, A. H. (1981). Kurtén, B., and E. Anderson. Pleistocene mammals of north america. Columbia Univ. Press, New York, 442 pp., 1980. Price $42.50.

- ^ Pohle, H. (1920) Lie Unterfamilie der Lutrinae. Archiv flir Naturgeschichte, 9(A): 1–247.

- ^ Nowak, R. M. (1979). North American Quaternary Canis, Monograph of the Museum of Natural History, The University of Kansas.

- ^ Perri, Angela R.; Mitchell, Kieren J.; Mouton, Alice; Álvarez-Carretero, Sandra; Hulme-Beaman, Ardern; Haile, James; Jamieson, Alexandra; Meachen, Julie; Lin, Audrey T.; Schubert, Blaine W.; Ameen, Carly; Antipina, Ekaterina E.; Bover, Pere; Brace, Selina; Carmagnini, Alberto; Carøe, Christian; Samaniego Castruita, Jose A.; Chatters, James C.; Dobney, Keith; Dos Reis, Mario; Evin, Allowen; Gaubert, Philippe; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Gower, Graham; Heiniger, Holly; Helgen, Kristofer M.; Kapp, Josh; Kosintsev, Pavel A.; Linderholm, Anna; Ozga, Andrew T.; Presslee, Samantha; Salis, Alexander T.; Saremi, Nedda F.; Shew, Colin; Skerry, Katherine; Taranenko, Dmitry E.; Thompson, Mary; Sablin, Mikhail V.; Kuzmin, Yaroslav V.; Collins, Matthew J.; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Gilbert, M. Thomas P.; Stone, Anne C.; Shapiro, Beth; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire; Wayne, Robert K.; Larson, Greger; Cooper, Alan; Frantz, Laurent A. F. (2021). "Dire wolves were the last of an ancient New World canid lineage". Nature. 591 (7848): 87–91. Bibcode:2021Natur.591...87P. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-03082-x. PMID 33442059. S2CID 231604957.

- ^ a b c Simpson, G. G. (1941). Large Pleistocene felines of North America. American Museum novitates; no. 1136.

- ^ Berta, A. (1987). Sabercat Smilodon gracilis from Florida and a discussion of its relationships (Mammalia, Felidae, Smilodontini).

- ^ Fedriani, Jose M.; Fuller, Todd K.; Sauvajot, Raymond M.; York, Eric C. (2000-10-01). "Competition and intraguild predation among three sympatric carnivores". Oecologia. 125 (2): 258–270. doi:10.1007/s004420000448. hdl:10261/54628. ISSN 1432-1939. PMID 24595837. S2CID 24289407.

- ^ Vu, Long. "Urocyon cinereoargenteus (gray fox)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ Van Valkenburgh, Blaire; Hayward, Matthew W.; Ripple, William J.; Meloro, Carlo; Roth, V. Louise (2016-01-26). "The impact of large terrestrial carnivores on Pleistocene ecosystems". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (4): 862–867. doi:10.1073/pnas.1502554112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4743832. PMID 26504224.

- ^ Anderson, E. (1984). Review of the small carnivores of North America during the last 3.5 million years. Special Publications of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, 8, 257–266.

- ^ Youngman, Phillip M. (1986-03-01). "The extinct short-faced skunk Brachyprotoma obtusata (Mammalia, Carnivora): first records for Canada and Beringia". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 23 (3): 419–424. doi:10.1139/e86-043. ISSN 0008-4077.

- ^ "About Rancho La Brea Mammals". Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. 2012-08-06. Archived from the original on 2017-10-28. Retrieved 2022-11-29.

- ^ DeSantis, L.R.G.; Shaw, C.A. (2018). "Sabertooth Cats with Toothaches: Impacts of Dental Injuries on Feeding Behavior in Late Pleistocene Smilodon Fatalis (Mammalia, Felidae) from Rancho la Brea (Los Angeles, California)". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 50 (6): 322567. doi:10.1130/abs/2018AM-322567.

- ^ Rincón, Ascanio D.; Prevosti, Francisco J.; Parra, Gilberto E. (2011-03-17). "New saber-toothed cat records (Felidae: Machairodontinae) for the Pleistocene of Venezuela, and the Great American Biotic Interchange". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (2): 468–478. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.550366. hdl:11336/69016. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 129693331.

- ^ Cope, E. D. (December 1880). "On the Extinct Cats of America". The American Naturalist. 14 (12): 833–858. doi:10.1086/272672. ISSN 0003-0147. S2CID 85137468.

- ^ a b c Tedford, Richard H.; Wang, Xiaoming; Taylor, Beryl E. (2009-09-03). "Phylogenetic Systematics of the North American Fossil Caninae (Carnivora: Canidae)". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 325: 1–218. doi:10.1206/574.1. ISSN 0003-0090. S2CID 83594819.

- ^ a b Spamer, E. E., Daeschler, E., & Vostreys-Shapiro, L. G. (1995). A study of fossil vertebrate types in the academy of natural sciences of philadelphia: taxonomic, systematic, and historical perspectives. Academy of Natural Sciences.

- ^ Kurten, B (1974) A History of Coyote-Like Dogs (Canidae, Mamalia). Acta. Zoo. Fennica 140:1-38.

- ^ Jones, C. A., Choate, J. R., & Genoways, H. H. (1984). Phylogeny and paleobiogeography of short-tailed shrews (genus Blarina).

- ^ a b c d e f g Cope, E. D. (1871). Preliminary report on the Vertebrata discovered in the Port Kennedy Bone Cave. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 12(86), 73–102.

- ^ Holmes, F. S. (1860). Post-Pleiocene Fossils of South-Carolina. Russell & Jones.

- ^ Simpson, G. G. (1945). Notes on Pleistocene and Recent tapirs. Bulletin of the AMNH; v. 86, article 2.

- ^ Ray, C. E., & Sanders, A. E. (1984). Pleistocene tapirs in the eastern United States. Contributions in Quaternary Vertebrate Paleontology: a Volume in Memorial to John E. Guilday. Carnegie Museum Natural History, Special Publication, 8, 283–315.

- ^ Dooley, A. C.; Scott, E.; Green, J.; Springer, K. B.; Dooley, B. S.; Smith, G. J. (2019). "Mammut pacificus sp. nov., a newly recognized species of mastodon from the Pleistocene of western North America". PeerJ. 7: e 6614. doi:10.7717/peerj.6614. PMC 6441323. PMID 30944777.

- ^ Pérez-Crespo, Víctor A.; Prado, José L.; Alberdi, Maria T.; Arroyo-Cabrales, Joaquín; Johnson, Eileen (February 2016). "Diet and Habitat for Six American Pleistocene Proboscidean Species Using Carbon and Oxygen Stable Isotopes". Ameghiniana. 53 (1): 39–51. doi:10.5710/AMGH.02.06.2015.2842. ISSN 0002-7014. S2CID 87012003.

- ^ a b Cope, E. D. (1883). "The Extinct Rodentia of North America (Continued)". The American Naturalist. 17 (4): 370–381. doi:10.1086/273328. ISSN 0003-0147. S2CID 222325765.

- ^ a b Hibbard, Claude W. (1955). "Notes on the Microtine Rodents from the Port Kennedy Cave Deposit". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 107: 87–97. ISSN 0097-3157. JSTOR 4064482.

- ^ a b Repenning, C. A., & Grady, F. (1988). The microtine rodents of the Cheetah Room fauna, Hamilton Cave, West Virginia, and the spontaneous origin of Synaptomys (No. 1853). USGPO,.

- ^ Frazier, M. K. (1981). A revision of the fossil Erethizontidae of North America. University of Florida.

- ^ Allen, J. A. (1904). A fossil porcupine from Arizona (Vol. 20). order of the Trustees, American Museum of Natural History.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Horn, George H. (1874). "Notes on Some Coleopterous Remains from the Bone Cave at Port Kennedy, Penna". Transactions of the American Entomological Society. 5: 241–245. doi:10.2307/25076311. ISSN 0886-1145. JSTOR 25076311.

- ^ Steadman, D. W. (1980). A review of the osteology and paleontology of turkeys (Aves: Meleagridinae). Contributions in Science, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 330, 131–207.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Parris, David C.; Daeschler, Edward (1995). "Pleistocene turtles of Port Kennedy Cave (late Irvingtonian), Montgomery County, Pennsylvania". Journal of Paleontology. 69 (3): 563–568. doi:10.1017/S0022336000034934. ISSN 0022-3360. S2CID 132442762.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Mercer, H. C. (1899). The bone cave at Port Kennedy, Pennsylvania, and its partial excavation in 1894, 1895 and 1896. (No Title).