Juan Granell Pascual

Juan Granell Pascual | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Juan Granell Pascual 1902 Burriana, Spain |

| Died | 1962 Madrid, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation(s) | engineer, official |

| Known for | politician, manager |

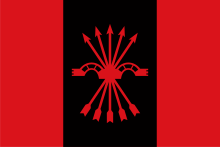

| Political party | Carlism, FET |

Juan Granell Pascual (1902-1962) was a Spanish politician, official and businessman. Politically he first supported the Carlist cause and served in the Republican Cortes in 1933–1936. After the Civil War he turned into a militant and zealous Francoist. His political career climaxed in the early 1940s; in 1939-1945 he was member of the FET executive Consejo Nacional, in 1940-1941 he was the civil governor and the provincial FET leader in Biscay, in 1940-1941 he served in Tribunal Especial para la Represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo, in 1941-1945 he was sub-secretary of industry in the Ministry of Industry and Commerce and member of the Instituto Nacional de Industria council. In 1943-1949 during two terms he was member of Cortes Españolas. In 1945-1953 he managed the state-run energy conglomerate ENDESA and was responsible for construction of the first coal-fired thermal power plant in Spain; he was also in executive bodies of numerous other companies.

Family and youth[edit]

The Granell family is of Catalan origin; in the region of Valencia it was first noted in the mid-13th century and in the area of Castellón in the late 14th century.[1] In the course of the centuries it got very branched and popular along all the Spanish Mediterranean coast and numerous individuals rose to publicly recognizable figures, but none of them has been identified as related to Granell Pascual.[2] His family branch originated from Bétera near Valencia[3] but in the early 18th century they settled in the port town of Burriana, south of Castellón.[4] From then on 4 successive generations lived in Burriana, including Juan's grandfather, Juan Bautista Granell Fandos.[5] His social status is unclear and none of the sources consulted provides information what he was doing for a living, though some suggest that the family owned a large "finca citrícola" on the right bank of the Mijares river and were growing lemons and oranges.[6] Granell Fandos’ son, Vicente Granell Blanch (1869-after 1940[7]), in 1892 married a girl from another family of local orange growers,[8] Dolores Pascual Mingarro.[9] The couple settled in Burriana and had at least 3 children, born in 1893–1902; Juan was the youngest one.

As a boy Juan first frequented a private school in Burriana.[10] In his early teens he became a boarder in the Jesuit Colegio de San José in Valencia,[11] where he was noted between 1915 and 1918.[12] At unspecified time though probably in the late 1910s he moved to Madrid to commence higher education and enrolled at Escuela de Mecánica y Electricidad, a Jesuit technical school currently known as Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingeniería.[13] It is not clear when he graduated as engineer; in 1928 he was referred to as “ingeniero electricista”.[14] It is neither known what he was doing for a living in the late 1920s; one scholar when discussing his career in the early 1930s describes Granell Pascual as “a successful engineer”,[15] but provides no details on his professional career. Also press of the early 1930s consistently referred to him, as “ingeniero”,[16] “ingeniero industrial”[17] or “ingeniero mecánico electricista”.[18]

In 1933[19] Granell married Aurelia Concepción Vicent Planes (1905-1999), a girl from the local bourgeoisie family also engaged in the orange business.[20] It is not clear whether the couple settled in Burriana[21] or in Madrid.[22] They had 6 children, born between the mid-1930s and the late 1940s: Juan María, María Begoña, Vicente, Jesús, Ignacio and Javier Granell Vicent.[23] None of them became a nationwide known figure, though some were recognized locally. Juan María,[24] Jesús[25] and Ignacio[26] worked as civil engineers, mostly in construction business; some held also teaching positions,[27] while Javier became the head surgeon in the public Madrid health service.[28] Currently the engineering tradition is cultivated by the third generation, as Granell Pascual's grandson Carlos Granell Ninot works in construction business and is the secretary of SPANCOLD, the engineering association focused on dams and hydrotechnical works.[29]

Early political engagements[edit]

None of the sources consulted provides information on political preferences of Granell's ancestors; in Burriana many Granells tended to sympathize with the conservatives.[30] Some data suggest that his father might have been related to Integrism[31] and that he remained a militant Catholic;[32] later propaganda prints claimed that Granell Pascual inherited the Traditionalist outlook, possibly highly flavored with Carlism, from his forefathers.[33] There is no information on his political engagements prior to late 1931, when Granell Pascual was listed among the Madrid Integrists who paid homage to the defunct Carlist king, Don Jaime.[34] He then joined the united Carlist organisation Comunión Tradicionalista and since early 1932 he was noted speaking at Carlist meetings in Burriana, accompanied by former Integrists like Manuel Senante.[35] In early 1933 latest he entered the provincial party executive, Junta Provincial,[36] and later during the year he used to speak at local rallies.[37]

During the 1933 electoral campaign to the Cortes the Castellón Carlists, led by Jaime Chicharro and Juan Bautista Soler, closed an alliance agreement with other right-wing organisations; Granell was included on the joint provincial list of candidates of Unión de Derechas. He campaigned focused on religious issues and protested alleged anti-Catholic governmental policy;[38] following some controversies related to a rival lerrouxista counter-candidate eventually Comisión de Actas declared him elected.[39] In the parliament he joined the Carlist minority[40] but remained on the back benches and some authors claim he went unnoticed in the chamber.[41] Following the October 1934 unrest he formed part of a commission which investigated the events in Barcelona[42] and in 1935 he co-signed a joint motion in Cortes[43] to prosecute Manuel Azaña.[44]

Granell did not feature prominently in the national Carlist organization; his only central role identified is membership in Tesoro de la Tradición, a financial branch of the executive.[45] He kept serving in the Castellón Junta Provincial; it was led by Juan Bautista Soler,[46] though some authors claim that Granell led the junta himself.[47] He remained engaged in regular local activities, like opening new círculos[48] or speaking at rallies, e.g. in Castellón[49] during so-called Gran Semana Tradicionalista,[50] in Onteniente[51] or Benicarló.[52] His particular focus was on confronting masonry.[53] The party propaganda presented him as a representative of “la nueva generación de tradicionalistas” and a “disciplined soldier” of the cause.[54]

Since 1936 there is scarcely any information on Granell during the following 4 years. Neither contemporary press nor historiography mention him as a candidate standing in the Cortes elections of 1936. It is not clear whether he was engaged in anti-Republican conspiracy and none of the sources consulted provides information on his fate during the Civil War. Some authors claim that he "supported the rebel faction", but provide neither details nor references.[55] Unlike in case of former combatants, none of numerous hagiographic press notes published during his later career in Francoist ranks refers to his wartime deeds. One literary work suggests that Granell and his family spent the war in hiding in Grao de Burriana[56] and emerged in public in July 1938.[57]

Political climax (1939-1945)[edit]

In early August 1939 Granell was nominated Delegado de Prensa y Propaganda in Valencia,[58] head of the regional Falange Española Tradicionalista press and media service;[59] in this role he also used to publish some militant Francoist propaganda articles in local press.[60] In September 1939 and as one of 13 tractable Carlists[61] he was nominated to the second Consejo Nacional of Falange,[62] and in March 1940 he was appointed as member to the newly established Tribunal Especial para la Represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo. Exact mechanism of his elevation is unclear; some authors speculate that it might have been related to the Jesuit influence, his own anti-masonic zeal and connections to pro-Franco collaborative faction within Carlism.[63] In October 1940 Granell assumed the post of civil governor of the province of Biscay.[64]

As civil governor Granell abandoned any Carlist sentiments he might have still nurtured and adopted a vehement, militant Falangist stand, pursued in terms of propaganda arrangements and personal appointments.[65] He found himself at odds with the Bilbao mayor and provincial Biscay FET leader, another Carlist José María Oriol, who attempted to cultivate moderate Traditionalist policy.[66] Following a series of clashes[67] Oriol resigned as FET jefe provincial in December 1940 and was replaced by Granell himself.[68] In February 1941 Oriol left also the position of Bilbao alcalde, and Granell emerged unchallenged as the key regime personality in the province. According to later homage article his focus was mostly on industry and social questions,[69] though he took part also in routine propaganda endeavors.[70] In April 1941 he ceased as member of the anti-masonic Tribunal.[71] In July 1941 Granell was released as civil governor and moved to central administration; he assumed the post of Subsecretario de industria in the Ministry of Industry and Commerce.[72]

As industry sub-secretary Granell identified 5 priorities: irrigation, electrification, coal production, fuel industry and transport.[73] He entered the council of INI[74] and worked closely with Suanzes on development of state-controlled conglomerates, especially ENDESA, Empresa Nacional de Electricidad.[75] He contributed also to re-structuring of the Falangist syndicates.[76] The British intelligence considered him so prominent a figure that they produced rumors about Granell.[77] In 1942 he was re-appointed to the 3rd Consejo Nacional of FET[78] and as its member in 1943 he automatically became member of the newly established Cortes Españolas;[79] he entered Comisión de Industria y Comercio.[80] His career went into decline in 1945; he was released from the sub-secretary post[81] and was not re-appointed to the 4th Falangist Consejo. However, upon expiry of his Cortes ticket he got it renewed from the pool of personal Franco's appointees. He briefly approached the minoritarian Carlist carloctavista faction and entered Consejo Permanente of the pretender Carlos VIII,[82] but was not among its protagonists.[83] The mainstream Javierista faction declared him a traitor and while some Falangists were allowed re-entry into Comunión, Granell along 5 other individuals was specifically listed as not eligible.[84]

Later career[edit]

Having left the Ministry of Industry in 1945 Granell assumed management of one of the flagship INI companies, ENDESA.[85] In corporate historiography he is recorded as ingenious, dedicated and enthusiastic manager, who used to visit construction sites during weekends.[86] As most of Spanish electricity was produced by hydrotechnical installations, his focus was on diversification and development of thermal power plants. These efforts bore fruit in 1949,[87] with opening of the first Spanish coal-fired plant in Compostilla;[88] it was also the first power plant built by ENDESA.[89] However, over time Granell developed discrepancies with Suanzes over the question of ownership of electricity infrastructure; some authors claim he advocated a joint public-private partnership against the Suanzes-advanced state-run model,[90] others suggest that the two went together rather well and that Granell actually advocated expropriation of private energy concessions.[91] It is not clear whether these issues contributed to Granell not having his Cortes ticket renewed in 1949, the year which marked his final exit from politics. Eventually Granell resigned from ENDESA management in 1953, according to some due to differences with Suanzes.[92]

Some authors claim that Granell “se retiró de la política para atender a sus negocios”,[93] but there is no evidence that he was running his own private business. Instead, he entered executive boards of numerous large companies. Some were partially controlled by INI, like the fuel giant Compañía Arrendataria del Monopolio del Petróleo CAMPSA, Empresa Nacional Hidroeléctrica del Ribagorzana ENHER[94] or Asbestos Españoles.[95] Some were strictly private enterprises, like the construction conglomerate Dragados y Construcciones, another construction firm Sociedad Boetticher y Navarro or the insurance company Unión Levantina.[96] Some were related to municipal authorities, like the credit company Casa de Valencia, which he presided since the late 1940s.[97] At least in some of these companies, like in Boetticher y Navarro, Granell performed high executive roles until the early 1960s.[98]

Since expiry of his Cortes ticket Granell remained politically inactive. However, he remained on excellent terms with the regime. In 1954 he was admitted at a private audience by Franco;[99] he spoke to caudillo in similar circumstances at least also in 1957,[100] 1958[101] and 1962.[102] He received Gran Cruz de Isabél la Católica, Gran Cruz del Mérito Civil[103] and Gran Cruz de la Orden de Cisneros.[104] Resident in Madrid,[105] he became the unofficial Burriana representative in the capital[106] and was credited for numerous local investments, be it the road and railway infrastructure development, water delivery and drainage system upgrades, refurbishment and enhancement of Guardia Civil offices, extension of piers and construction of new buildings in the harbor,[107] saving local college from closure[108] and especially reconstruction of the iconic El Salvador church bell-tower, blown up by retreating Republican troops.[109] Already in the 1940s he was declared hijo predilecto of Burriana;[110] after death[111] a large plaza was named after him,[112] to be renamed in the post-Francoist era.

See also[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Significado de Granell, [in:] Mis Apellidos service, available here

- ^ the list of individuals who became public figures and were contemporaries to Juan Granell Pascual included Ramon Granell Pascual, Amado Granell Mesado, Jeroni Ferran Granell i Manresa, Francisco Granell Felis, Antonio Fillol Granell, Juan Granell Acosta and Enrique Sapena Granell; none has been identified as his relative

- ^ Frances Granell got married in Betera in 1655, Francesc Granell entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ Francisco Granell Andreu got married in Burriana in 1718, Francisco Granell Andreu entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ Juan Bautista Granell Fandos entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ Emilio Laguna, Un ejemplar centenario de Sophora japónica ‘Pendula’, [in:] Research Gate service 2012, p. 6

- ^ Era su padre, [in:] Buris-Ana 66 (1963), p. 7

- ^ El Pueblo 11.03.15, available here

- ^ Dolores Pascual Mingarro entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ see homage article to his former schoolmaster, Heraldo de Castellón 24.07.28, available here

- ^ La Correspondencia de Valencia 07.12.15, available here

- ^ La Correspondencia de Valencia 12.12.15, available here, also Las Provincias 25.03.18, available here

- ^ Gonzalo Anes Alvares de Castrillón, Santiago Fernández Plasencia, Juan Temboury Villareio, Endesa en su historia (1944-2000), Madrid 2010, ISBN 9788461459063, p. 68

- ^ Heraldo de Castellon 24.07.28, available here

- ^ Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and crisis in Spain 1931-1939, London 2008, ISBN 9780521207294 , p. 123

- ^ El Cruzado Español 30.10.31, available here

- ^ Heraldo de Castellon 10.06.33, available here

- ^ see Granell Pascual at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ Heraldo de Castellon 10.06.33, available here

- ^ the family of her father, the Vicent Real, were engaged in the orange growing business, El Pueblo 08.06.09, available here

- ^ though since early 1934 Granell served as deputy to the Cortes it seems that his permanent residence was in Burriana, as at the time he was holding provincial jobs in the Castellón party organization, see e.g. El Siglo Futuro 05.03.33, available here

- ^ in the early 1930s he was listed among the Madrid Integrists, El Cruzado Español 30.10.31, available here

- ^ in the necrological note of 1963 the only daughter was referred to as Maria Aurelia, Hoja Oficial de Lunes 31.12.62, available here, but in the interview in a local periodical she appears as Maria Begoña, Era su padre, [in:] Buris-Ana 66 (1963), p. 7

- ^ Juan Granell Vicent, [in:] Expension service, available here

- ^ Jesús Granell Vicent necrological note, [in:] Esquelas ABC 29.08.16, available here

- ^ Ignacio Granell Vicent entry, [in:] Structurae service, available here

- ^ for Ignacio see Puente sobre el río Gállego en la Ronda Este de Zaragoza, available here, for Juan María see BOE 27.02.71, available here

- ^ Javier Granell Vicent profile, [in:] LinkedIn service, available here

- ^ Carlos Granell Ninot profile, [in:] LinkedIn service, available here

- ^ compare José Luis Giménez Julia, El maurisme i la dreta conservadora a la Plana [PhD thesis Universitat Jaume I], Villa-real 2015, e.g. pp. 371, 384, 387, 398

- ^ in the 1880s Granell’s father declared adhesion to the Integrist leader Ramón Nocedal, El Siglo Futuro 15.11.89, available here

- ^ e.g. in 1900 Granell’s father signed a letter of protest against persecutions of the church, El Estandarte Católico 14.04.00, available here

- ^ a post-mortem hagiographic article claims that Granell absorbed Catholic outlook enveloped in generic Traditionalism from his father; the article hints also at his father’s sympathy towards Carlism, as allegedly he used to sing “qué bien te siente, qué bien te está, la boina blanca y la colorá”, J. Calpe Usó, Semblanza política, [in:] Buris-Ana 66 (1963), p. 5

- ^ El Cruzado Español 30.10.31, available here

- ^ Las Provincias 05.04.32, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 05.01.33, available here

- ^ Las Provincias 20.04.33, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 03.11.33, available here

- ^ Luz 10.01.34, available here

- ^ Calpe Usó 1963, p. 5

- ^ Vicent Sampedro Ramo, Los hijos de la viuda: La masonería en la ciudad de Alicante (1893-1939), Alicante 2017, ISBN 9788497175494, p. 385

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 343

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 21.10.35, available here

- ^ La Libertad 14.03.35, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 29.11.34, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 26.04.34, available here; some sources claim that Granell was leading the provincial Carlist organisation in Castellón but provide no sources, see Pablo Bahillo Redondo, El Tribunal Especial para la represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo (Termc). 80 años después, [in:] El Obrero 04.06.20, available here

- ^ Sampedro Ramo 2017, p. 385

- ^ El siglo Futuro 12.06.34, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 04.05.35, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 08.05.35, available here

- ^ La Libertad 27.03.35, available here

- ^ Heraldo de Castellon 04.05.35, available here

- ^ e.g. in 1935 Granell took part in a grand anti-masonic rally and according to another Burriana republican deputy and active freemason, Vicent Marco Miranda, Granell developed a particular knack against the freemasonry, Vicent Sampedro Ramo, En situació vigilada: la condemna de Vicent Sos Baynat per Tribunal de Repressió de la Maconeria i el Comunisme, [in:] Millars XXXIV (2011), p. 228

- ^ Jesús Evaristo Casariego, El tradicionalismo español. Su historia, su ideario, sus hombres, Madrid 1934, inserts between pages 120 and 121

- ^ Pablo Bahillo Redondo, El Tribunal Especial para la represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo (Termc). 80 años después, [in:] El Obrero 04.06.20, available here

- ^ Juan Granell is one of the protagonists of a novel El niño de la peonza by José Barcelo (2013). The novel, though based on speculative reconstruction of fate of a German submarine sailor, serving in the Mediterranean during World War Two, is literary fiction. It is not clear whether the author based his Granell-related narrative on any documents, though along his maternal line Barcelo is personally related to Burriana. In the novel Granell and his family hide in "Grao" during the Civil War ("Me esconderé con mis padres en el Grao", says Asuncion, the daughter of Granell). Some other episodes of the novel, like his efforts to get the bell-tower reconstructed, are confirmed by historiographic sources

- ^ in El niño de la peonza Granell returns to Burriana as a high Francoist official in July 1938

- ^ La Vanguardia 05.08.39, available here

- ^ Calpe Usó 1963, p. 5, also Federico Martínez Roda, Valencia y las Valencias: su historia contemporánea (1800-1975), Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788486792893, p. 225

- ^ in a PhD work Granell is once listed as contributing to buildup of Francoist ideology by developing the cult of the fallen, see a reference to his late 1939 article in a local periodical Levante, Zira Box Varela, La fundación de un régimen. La construcción simbólica del franquismo [PhD thesis Complutense], Madrid 2008, ISBN 9788469209981, p. 137

- ^ Aurora Villanueva Martínez, El carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo, 1937-1951, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788487863714, pp. 64-65

- ^ El Progreso 13.09.39, available here

- ^ Sampedro Ramo 2017, p. 385

- ^ El Progreso 20.10.40, available here

- ^ in Bilbao Granell was “un carlista que ha dejado de incordiar con cualquier idea de restauración”, and acted as a vehement Falangist, Martí Marín Cobrera, Los gobernadores civiles del franquismo 1936-1963. Seis personajes en busca de autor, [in:] Historia y política: Ideas, procesos y movimientos sociales 29 (2013), p. 289

- ^ Alfonso Ballestero, José Ma de Oriol y Urquijo, Madrid 2014, ISBN 9788483569153, p. 77

- ^ officially Oriol left due to “múltiples ocupaciones, aumentadas últimamente por cuidados familiares”, Mikel Urquijo Agirreazkuenaga (ed.), Bilbao desde sus alcaldes: Diccionario biográfico de los alcaldes de Bilbao y gestión municipal en la Dictadura vol. 3, Bilbao 2008, ISBN 9788488714145, p. 208

- ^ Ballestero 2014, p. 65

- ^ Calpe Usó 1963, p. 5

- ^ e.g. on March 10, 1941 he took part in domesticated Carlist feast of Martires de la Tradición, formatted along the new unificated Falangist lines, Urquijo Agirreazkuenaga 2008, p. 224

- ^ Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Guadalajara 07.04.41, available here

- ^ Diario de Burgos 13.07.41, available here

- ^ Juan Granell, La industrialización de España, [in:] Información Comercial Española 96 (1944), p. 3

- ^ Antonio Bernardo Reyes, Paco Báez Baquet, Paco Puche, “Fiebre del oro blanco” en la Costa del Sol y en la serranía de Ronda, [in:] Rebelion service 2013, p. 2, available here

- ^ Martínez Roda 1998, p. 225

- ^ e.g. in January 1944 he was nominated to a commission tasked with classification of syndicates, Imperio 09.01.44, available here

- ^ in May 1942 the so-called "sib" produced by a unit named Political Warfare Executive read that "The Germans have bribed Juan Granell, the Under Secretary of State for Industry, who has just returned from Italy, to fix it that, as a result of the discussions which the Spanish trade mission is having in the Argentine, a good proportion of the tinned meat for which they are bargaining shall in fact contain certain small bulk goods vital to Germany, such as industrial diamonds, etc", quoted after Lee Richards, Whispers of War: Underground Propaganda Rumour-Mongering in the Second World War, Peacehaven 2010, ISBN 9780954293642, pp. 157-158

- ^ on position #49; in 1939 he was nominated on position #77, El Adelanto 24.11.42, available here

- ^ see his 1943 ticket at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ Boletín Oficial de las Cortes Españolas 1 (1943), p. 18

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 07.08.45, available here

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 1998, p. 214

- ^ e.g. Granell is not mentioned a single time in a monograph on Carloctavismo, compare Francisco de las Heras y Borrero, Un pretendiente desconocido. Carlos de Habsburgo. El otro candidato de Franco, Madrid 2004, ISBN 8497725565

- ^ in November 1942 the Carlist jefe delegado Manuel Fal Conde issued a note which allowed re-entry into the Comunión to these which by virtue of mistake or misinformation had joined FET; the exception was made in case of Rodezno, José María Oriol, José Luis Oriol, Esteban Bilbao, Julio Muñoz Aguilar and Granell, Mercedes Peñalba Sotorrío, Entre la boina roja y la camisa azul, Estella 2013, ISBN 9788423533657, p. 143

- ^ Gonzalo Anes Alvares de Castrillón, Santiago Fernández Plasencia, Juan Temboury Villareio, Endesa en su historia (1944-2000), Madrid 2010, ISBN 9788461459063, p. 68

- ^ Alvares de Castrillón, Fernández Plasencia, Temboury Villareio 2010, p. 68

- ^ Alvares de Castrillón, Fernández Plasencia, Temboury Villareio 2010, pp. xi, 68, 294

- ^ Hoja Oficial de Lunes 15.08.49, available here

- ^ Calpe Usó 1963, p. 5

- ^ Alvares de Castrillón, Fernández Plasencia, Temboury Villareio 2010, p. 68

- ^ Antonio Gómez Mendoza, De mitos y milagros: el Instituto Nacional de Autarquía, 1941-1963, Barcelona 2000, ISBN 9788483382257, pp. 31, 74-77, 97

- ^ Alvares de Castrillón, Fernández Plasencia, Temboury Villareio 2010, p. 68

- ^ Alvares de Castrillón, Fernández Plasencia, Temboury Villareio 2010, p. 68

- ^ E. Aznar Colino, Aproximación a la Historia de la Empresa Nacional Hidroeléctrica del Ribagorzana, Zaragoza 2015 [research paper], p. 8

- ^ Antonio Bernardo Reyes, Paco Báez Baquet, Paco Puche, “Fiebre del oro blanco” en la Costa del Sol y en la serranía de Ronda, [in:] Rebelion service 2013 p. 2, available here

- ^ Hoja Oficial de Lunes 31.12.62, available here

- ^ Hoja Oficial de Lunes 31.01.49, available here

- ^ Imperio 18.10.62, available here

- ^ ABC 04.02.54, available here

- ^ Diario de Burgos 25.07.57, available here

- ^ Diario de Burgos 30.10.58, available here

- ^ Imperio 18.10.62, available here

- ^ Hoja Oficial de Lunes 31.12.62, available here

- ^ Pablo Bahillo Redondo, El Tribunal Especial para la represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo (Termc). 80 años después, [in:] El Obrero 04.06.20, available here

- ^ in Madrid Granell lived at Calle Diego de León, Joaquín Urios, Evocacion [in:] Buris-Ana 66 (1963), p. 7

- ^ Recordando a don Juan Granell Pascual, [in:] Buris-Ana 66 (1963), p. 4

- ^ Un ex-alcalde, D. Miguel Gil Viñes, hace balance de la ayda recibida de D. Juan Granell en el tiempo de su gestión municipal, [in:] Buris-Ana 66 (1963), p. 6

- ^ Joaquín Cardenal, Deuda de gratitud, [in:] Buris-Ana 66 (1963), p. 5

- ^ Entrevista, [in:] Buris-Ana 66 (1963), p. 8

- ^ Vida social 1941 entry, [in] Valenpedia service, available here

- ^ Granell died due to angina pectoris, Burriana de luto, [in:] Buris-Ana 66 (1963), p. 4

- ^ compare a postcard from the 1980s, [in:] Todocoleccion service, available here, also Mediterraneo 17.10.67, available here

Further reading[edit]

- José Barcelo, El niño de la peonza, Madrid 2013, ISBN 9781494295875

- Miguel Gil Viñes, Un ex-alcalde, D. Miguel Gil Viñes, hace balance de la ayda recibida de D. Juan Granell en el tiempo de su gestión municipal, [in:] Buris-Ana 66 (1963), p. 6

- J. Calpe Usó, Semblanza política, [in:] Buris-Ana 66 (1963), pp. 5, 9

- Joaquín Urios, Evocacion [in:] Buris-Ana 66 (1963), p. 7

External links[edit]

- 20th-century Spanish businesspeople

- Businesspeople from the Valencian Community

- Carlists

- Civil governors of Spanish provinces

- Endesa

- Grand Cross of the Order of Civil Merit

- Members of the Congress of Deputies (Spain)

- Members of the Congress of Deputies of the Second Spanish Republic

- People from Burriana

- Recipients of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

- Spanish anti-communists

- Spanish monarchists

- Spanish Roman Catholics

- 1902 births

- 1962 deaths