Draft:History of Morocco (1666–1912)

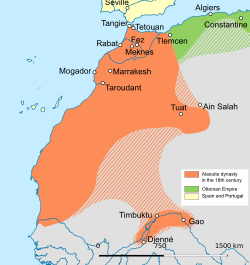

The Alawi Sultanate (Arabic: السلطنة العلوية), officially known as the Sharifian Sultanate (Arabic: السلطنة الشريفة) and colloquially as the Sultanate of Morocco, was the state led by the Moroccan Alawi dynasty from their rise to power in 1666 to the Treaty of Fes marking the start of the French protectorate in 1912.

During this period, the Alawi dynasty would take control of the sultanate after the collapse of the Saadi and Dilaid dynasties, and unify Morocco under their control. The sultanate would know a resurgence and a golden age during the reign of Moulay Ismail.

This period is also marked by catastrophic demographic collapse, as Morocco's population fell from around 7 million in the 1590s to 2.69 million in 1820 because of a series of plagues and other natural disasters throughout the 1700s and early 1800s.

Etymology[edit]

Morocco, since Saadi rule, was referred to as the Sharifian sultanate[citation needed]. This was rendered in French as l'Empire chérifien (lit. 'the Sharifian empire').[3] It was referred to as Sultanate of Morocco by Anglophones.[4] The Alaouites were at first known as the Sharifs of Sijilmassa or Sharifs of Sous.[5]

History[edit]

Origins of the Alawi dynasty[edit]

The ruling dynasty of the Sharifian Sultanate, the Alawis, rose from the oasis of Sijilmassa. Their ancestors are believed to have immigrated from the Hejaz in the 13th century during a drought that affected the region.[6][7] The founder of the dynasty in Morocco is believed to be Moulay Hassan ben al-Qasim Al-Dakhil, known for his deep piety, who established his lineage in Sijilmassa. Upon his death, he left behind a son, Mohamed Abu Abd Allah, who in turn had only one descendant bearing the same name as his grandfather. One of this descendant's sons, Ali al-Charif, undertook the pilgrimage to Mecca at an unspecified date and participated in the the jihad efforts in islamic Al-Andalus. He declined to settle in Granada at the request of the scholars of the city but instead spent many years in Fez and Sefrou before returning to Tafilalt.[7]

Rise of the Alawi dynasty (1640-1672)[edit]

Collapse of Saadi rule[edit]

The rise of the Alawis came in a context of religious and social unrest and increasing European pressure in the country's coastal cities.[7][5][8] The Saadi dynasty ruled over Morocco since the second half of the 16th century after triumphing in a long civil war against the decaying Wattasid dynasty. However, by the early 1600s, the sultanate was on the verge of total collapse. Moreover, a plague epidemic, likely imported from Spain, occured in the 1590s and early 1600s and ravaged Morocco.[7]

The Saadi sultan Ahmad Al-Mansur (1578-1603) would chose one of his least capable son as heir, which would prove terribly detrimental to the survival of his dynasty[8]. Following his death, approximately half of the Saadi dynasty's existence was marked by armed conflicts for the throne between his sons and other rival factions. Weak control over internal affairs and inability to resist foreign interference led to the rise of separatist movements. Excessive taxation further burdened the population, who were ready to support any learders capable of alleviating tax pressure.[7][8]

Early Alawi expansion[edit]

In 1637, Moulay al-Charif (1631-1636), the leader of the Alawi dynasty, was arrested and deported to Sous by Cheikh Bu Dmi’a of Tazerwalt, after expressing his discontent with Cheikh Bu Dmi’a's expanded influence in Tafilalt, following a dispute with the inhabitants of the qsar of Tabouasamt in 1631 or 1633.[7][9] Upon his release and return to Tafilalt, Moulay al-Charif discovered that he had been abandoned by his supporters, who had meanwhile proclaimed his son, Moulay Mohammed ibn al-Charif, in his place.[7]

Moulay Mohammed expelled the emir of Tazerwalt from Tafilalt in 1640. Encouraged by this success, the new Alawi leader embarked on the conquest of Draa and the northeastern regions of Morocco, where he secured the submission of the Arab tribes of Upper Guir, also gaining control of Oujda in 1641 and Touat in 1645. He also ventured into territories under Ottoman rule, reaching the outskirts of Tlemcen and Nedroma, but quickly turned back after he received threats from Pasha of Algiers.[7]

During his reign, he clashed many times with the Zaouia of Dila, who became a rival power competing for total control of Morocco after the total collapse of the Saadis. In 1646, Sijilmassa was sacked by Dillaite troops, after Moulay Mohammed was defeated in the battle of El Qa'a by the Dilaite leader Mohammed al-Hajj bin Mohammed.[10][11] The Alawis ended up losing vast swaps of lands to the Dilaites, most importantly all the territories below the El Ayach mountains, and even became subjects of the Dilaites. In 1649 Mohammed al-Hajj bin Mohammed was proclaimed sultan in Fez after the death of the last Saadi sultan Ahmad Al-Abbas, a move which sparked a revolt in the city. Profiting from this situation, Muhammad Ibn Sharif chose to intervene to take the capital, but was defeated in a battle near Dahr Erremka on August 19, 1649.[7][12] The Dilaites pursued him to Sijilmassa where they sacked the city a second time.[7]

Between 1665 and 1670, Moulay Rachid brought most of the country under control of the Alawi dynasty and became the first Alawi sultan of Morocco following his Conquest of Marrakesh in 1668.[6]

Apogee under Moulay Ismail (1672-1727)[edit]

In 1672, Moulay Rachid died in an accident and left power to his brother, Moulay Ismail. Moulay Ismail consolidated power despite rebellion from other family members, notably his nephew Ahmed ben Mehrez. Ben Mehrez died in battle near Taroudant in 1686.[6]

Thirty years civil war (1727-1757)[edit]

Reign of Mohammed III (1757-1790)[edit]

The situation in Morocco gradually stabilized following Moulay Abdellah's accession to throne, but it was under the reign of Sidi Mohammed ben Abd Allah (1757-1790) that the country truly emerged from the civil war.[7]

Decline (1790-1894)[edit]

Reign of Moulay Yazid[edit]

Reign of Moulay Slimane[edit]

Following his accession, Moulay Slimane could not successfully establish his authority over his brothers Moulay Hisham, Moulay Hussayn, and Moulay Maslama, and faced opposition from the dissenting population in Chaouia and Haha regions. It took him seven years of concerted efforts and military operations to achieve his goals. However, shortly after consolidating his throne, he confronted the consequences of the devastating plague epidemic that swept through Morocco in 1799-1800.[7]

Reign of Moulay Abderrahmane ben Hicham[edit]

Reign of Moulay Mohammed ben Abderrahmane[edit]

War of Tetuan[edit]

Reign of Moulay Hassan ben Mohammed[edit]

Collapse and French protectorate (1894-1912)[edit]

Ahmed al-Hiba, the son of Ma al-'Aynayn, the religious leader who founded the city of Es-Smara.

Government and politics[edit]

Makhzen[edit]

Judiciary[edit]

Military[edit]

Foreign relations[edit]

Relations with the British Empire[edit]

In a letter from Moulay Ismail to King James II of England, dated February 16, 1698, the Moroccan sultan invited King James II to consider embracing Islam or reverting to Anglicanism, and advised him to reside in Lisbon, facilitating a return to England away from French influence.[13]

The French colonization of Algeria led to a gradual erosion of trust between England and Morocco in the late 1830s.[7][13]

In 1860, both the French and British governments sent a delegation to propose the abolition of slavery to the Moroccan government.[13]

Relations with the Ottoman Empire[edit]

Under the reign of Mohammed III, Morocco would choose for the first time a policy of positive reconciliation with the Ottoman Empire after a long period of stagnation, which aligned with the country's broader initiative of opening up to the West, and was not achieved to this scale before.[13]

Relations with the Netherlands[edit]

During the thirty years civil war, the Dutch managed to oust the French from Moroccan maritime trade, and shared in the commerce passing through the country's four principal ports: Tétouan, Salé, Safi, and Agadir.[7]

Moulay Abdallah was the first Alawi sultan to sign a "treaty of peace and security" with a European state, the Netherlands, in 1750. This treaty ensured free trade between the two countries and established the first permanent European consulates in Morocco.[7]

Relations with the United States of America[edit]

The Sultanate of Morocco was the first country to de facto recognize the United States on June 23, 1777.[14][15] Sultan Mohammed III signed a decree granting ships from the newly-independent country protection and free access to Moroccan ports.[16] The Sultan previously expressed his desire to be a "friend of the Americans".[16] Morocco formally recognized the United States on June 23, 1786, when a treaty of peace and friendship was signed.[17]

Culture and society[edit]

During the 18th century, a number of Tachelhit poets arose including Mohammed Awzal in Taroudant and Sidi Hammou Taleb in Moulay Brahim.[18]

Cobalt sourced from the Bou Azzer mine, near Ouarzazate, was commonly used as insecticide and rodenticide by Moroccans after being mixed with arsenate.[19]

Mass media[edit]

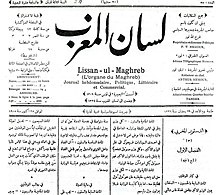

During modernization attempts for the Moroccan state under Moulay Abdelhafid to counter European influence, a draft constitution was published in the October 1908 issue of newspaper Lissan-ul-Maghreb in Tangiers.[20] The 93-article draft emphasized and codified the concepts of separation of powers, good citizenship, and human rights for the first time in the country's history.[20][21]

The draft, which was written by an anonymous author and was never signed by Moulay Abdelhafid, was inspired by the late 19th century constitutions of the Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and Persia.[22] In 2008, al-Massae claimed that the draft was written by members of a "Moroccan Association of Unity and Progress" composed of an elite close to Moulay Abdelhafid which supported the toppling of his predecessor, Moulay Abdelaziz.[22][23]

Economy[edit]

Agriculture[edit]

In pre-colonial Morocco, the predominant economic structure was centered around a rural subsistence model. Local farms were commonly held collectively, known as bled el jemâa. Established customs regulated land usage and distribution among families.[24] Despite economic setbacks occurring periodically, civil conflicts at both national and local levels and the primitive tools employed, there remained a significant emphasis on soil exploitation and agriculture constituted the primary occupation for the majority of rural inhabitants. Numerous lands became contested territories among various groups and tribes, which sometimes prompted the Makhzen to intervene in order to settle the disputes.[13]

Pierre Tralle, a French prisonner who also participated in the construction of Meknes over a seven-year period until 1700, highlighted in his report on the Moroccan situation the fertility of the land which he considered to be adapted to producing high-quality crops.[13]

Despite opening to trade in the late 19th century, Morocco faced limitations due to inadequate agricultural surplus and the antiquated transportation system, which hindered commercial activities. Foreign land ownership was largely unattainable before colonization, even though European powers secured legal exceptions allowing land speculation around major harbors through treaties such as the Treaty of Madrid in 1880 and the Treaty of Algeciras in 1906.[24]

During the latter half of the 19th century, there was an increased interest on irrigation and agricultural activities, particularly under the reign of Mohammed IV, sparked when he was still the caliph of Marrakech. This interest lead to the creation of various water sources in the region, and the construction of a canal originating from Wadi N'Fiss, as well as another canal named Fitout River which transported water from Tastaout to the plains encompassing Zemrane, Rahamna, and Sraghna. Throughout the 19th century, the Chaouia region rose as an important grain and livestock exporting hub through the port of Anfa, despite governmental policies restricting exports.[13]

An important shift in the types crops cultivated was observed in many regions prior to the establishment of the protectorate. The cultivation of olive trees, once prevalent across the coastal plains along the Atlantic coastal regions and the Rif, significantly declined.[13]

The Atlantic plains were renowned for the quality of their wheat, barley, and abundant vineyards, while vegetable cultivation was primarily concentrated near urban centers. Morocco also produced oranges, almonds, walnuts and figs. The introduction of new crops, such as aloe vera from the Americas, and potatoes from Europe, affected agriculture in Morocco. During the 19th century, the cultivation of plants like henna, flax, hashish, and turmeric gained prominence. Forested areas retained their original situation and composition, comprising oak and argan trees, and other species like willows, junipers, and pines.[13]

Taxation[edit]

During Moulay Ismail's reign, the sultanate's revenues primarily derived from taxes, with the two main sources being the Ashur and the Ghrama. The Ashur was collected in kind, constituting one-tenth of all agricultural produce, while the Ghrama was paid in cash according to individuals' wealth. The governors determined the amount of these taxes based on their knowledge of the population and the state of harvests.[7]

Demographics[edit]

Saadi era[edit]

1590-1610 plague epidemic[edit]

During the reign of Ahmad al-Mansur, the Saadi sultanate was plagued by famine and pestilence for nearly five years. A plague epidemic, which originated in Spain, was brought to Morocco by Sephardic Jews, Andalusian Moors, Moriscos, and Hornacheros who had been fleeing persecution, in what was islamic Al-Andalus, since 1492. This resulted in the depletion of livestock and crops, depopulation of urban and rural areas, total societal breakdown, and severe damage to the sugar industry, a vital component of the Saadi economy.[7]

The plague, following a series of natural disasters since the early 16th century, reached its peak in 1598, subsided briefly, then intensified until 1607 or 1608, claiming between a third and half of the population, which before the plague did not exceed 7 million. This also played a key role in the destruction of the administrative infrastructure established by the Saadi rulers, which contributed to the fall of the dynasty 60 years later. Ahmad al-Mansur is believed to have been himself killed by the plague, in 1603.[7]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Leared, Arthur (1876). Morocco and the Moors.

- ^ Maddison, Angus (2007-09-20). Contours of the World Economy 1-2030 AD: Essays in Macro-Economic History. Oxford University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-19-164758-1.

- ^ Laskier, Michael M. (2019-09-01). "Prelude to Colonialism: Moroccan Muslims and Jews through Western Lenses, 1860–1912". European Judaism. 52 (2): 111–128. doi:10.3167/ej.2019.520209. ISSN 0014-3006.

- ^ Leared, Arthur (1879). A Visit to the Court of Morocco. S. Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington.

- ^ a b Laroui, Abdallah (2016). مجمل تاريخ المغرب [The entire history of Morocco] (in Arabic). المركز الثقافي العربي (published 1984). ISBN 9789953681832.

- ^ a b c Cory, Stephen (2020), "The Making of the Maghrib: Morocco (1510-1822)", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.691, ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4, retrieved 2024-04-06

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Abitbol, Michel (2014). Histoire du Maroc (in French). Éditions Perrin. doi:10.3917/perri.abitb.2014.01. ISBN 978-2-262-03816-8.

- ^ a b c Harakat, Ibrahim (2011). المغرب عبر التاريخ ج2 (in Arabic). دار الرشاد الحديثة. ISBN 9781000079852.

- ^ ibn Muḥammad Ifrānī, Muḥammad al-Ṣaghīr. Nozhet-Elhâdi: histoire de la dynastie Saadienne au Maroc 1511-1670, Volume 3 [History of the Saadi dynasty in Morocco] (in French).

- ^ trans. from Arabic by Eugène Fumet, Ahmed ben Khâled Ennâsiri. Kitâb Elistiqsâ li-Akhbâri doual Elmâgrib Elaqsâ [" Le livre de la recherche approfondie des événements des dynasties de l'extrême Magrib "], vol. IX : Chronique de la dynastie alaouie au Maroc (PDF) (in French). Ernest Leroux. p. 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-10-04. Retrieved 2021-10-23.

- ^ Ibn Khalid al-Nasiri, Ahmad (1894). Kitâb al-Istiqsa li-Akhbar Al-Maghrib duwwal al-Aqsa, Tome V (in French).

- ^ Houdas, Octave (1886). Le Maroc de 1631 à 1812 / de Aboulqâsem ben Ahmed Ezziâni [Morocco from 1631 to 1812 / from Aboulqâsem ben Ahmed Ezziâni]. Ernest Leroux.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Harakat, Ibrahim (2016). المغرب عبر التاريخ ج3 (in Arabic). دار الرشاد الحديثة. ISBN 9781000079869.

- ^ Högger, Daniel (2015). The recognition of states : a study on the historical development in doctrine and practice with a special focus on the requirements. Zürich. ISBN 978-3-643-80196-8. OCLC 918793836.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "U.S. Relations With Morocco". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2022-12-18.

- ^ a b Roberts, Priscilla H.; Tull, James N. (1999). "Moroccan Sultan Sidi Muhammad Ibn Abdallah's Diplomatic Initiatives toward the United States, 1777-1786". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 143 (2): 233–265. ISSN 0003-049X. JSTOR 3181936.

- ^ "Morocco - Countries - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 2022-12-18.

- ^ Ruiz, Teofilo Fabian (2018). The western Mediterranean and the world: 400 CE to the present. The Blackwell history of the world. Hoboken (N. J.): Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8817-3.

- ^ CHAHID, Soufiane. "Ressources minières : L'épopée méconnue du cobalt marocain". L'Opinion (in French). Retrieved 2024-04-09.

- ^ a b Naciri, Khaled (2009-07-03). "Le droit constitutionnel marocain ou la maturation progressive d'un système évolutif". Saint Joseph University of Beirut. Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ Ismaili, Omar; Abdelouahed, Aïcha (2022-07-01). "Les questions de l'éducation et des langues dans l'histoire constitutionnelle marocaine" (PDF). Akofena (6).

- ^ a b Aïssaoui, Saïd (2017-12-15). "En 1908, un projet de constitution évoquait les libertés individuelles au Maroc". Yabiladi (in French). Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ "1908–2008: فَلنَحْتَفِل بمئوية المسألة الدستورية في المغرب". مغرس. Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ a b Salem, Ariane (2021). The Negative Impacts of Colonization on the Local Population: Evidence from Morocco