Cyber kill chain

The cyber kill chain is the process by which perpetrators carry out cyberattacks.[2] Lockheed Martin adapted the concept of the kill chain from a military setting to information security, using it as a method for modeling intrusions on a computer network.[3] The cyber kill chain model has seen some adoption in the information security community.[4] However, acceptance is not universal, with critics pointing to what they believe are fundamental flaws in the model.[5]

Attack phases and countermeasures[edit]

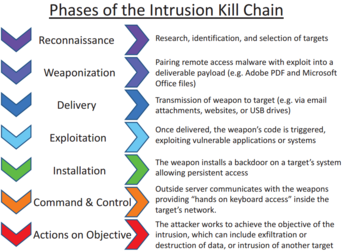

Computer scientists at Lockheed-Martin corporation described a new "intrusion kill chain" framework or model to defend computer networks in 2011.[6] They wrote that attacks may occur in phases and can be disrupted through controls established at each phase. Since then, the "cyber kill chain" has been adopted by data security organizations to define phases of cyberattacks.[7]

A cyber kill chain reveals the phases of a cyberattack: from early reconnaissance to the goal of data exfiltration.[8] The kill chain can also be used as a management tool to help continuously improve network defense. According to Lockheed Martin, threats must progress through several phases in the model, including:

- Reconnaissance: Intruder selects target, researches it, and attempts to identify vulnerabilities in the target network.

- Weaponization: Intruder creates remote access malware weapon, such as a virus or worm, tailored to one or more vulnerabilities.

- Delivery: Intruder transmits weapon to target (e.g., via e-mail attachments, websites or USB drives)

- Exploitation: Malware weapon's program code triggers, which takes action on target network to exploit vulnerability.

- Installation: Malware weapon installs an access point (e.g., "backdoor") usable by the intruder.

- Command and Control: Malware enables intruder to have "hands on the keyboard" persistent access to the target network.

- Actions on Objective: Intruder takes action to achieve their goals, such as data exfiltration, data destruction, or encryption for ransom.

Defensive courses of action can be taken against these phases:[9]

- Detect: Determine whether an intruder is present.

- Deny: Prevent information disclosure and unauthorized access.

- Disrupt: Stop or change outbound traffic (to attacker).

- Degrade: Counter-attack command and control.

- Deceive: Interfere with command and control.

- Contain: Network segmentation changes

A U.S. Senate investigation of the 2013 Target Corporation data breach included analysis based on the Lockheed-Martin kill chain framework. It identified several stages where controls did not prevent or detect progression of the attack.[1]

Alternatives[edit]

Different organizations have constructed their own kill chains to try to model different threats. FireEye proposes a linear model similar to Lockheed-Martin's. In FireEye's kill chain the persistence of threats is emphasized. This model stresses that a threat does not end after one cycle.[10]

- Reconnaissance: This is the initial phase where the attacker gathers information about the target system or network. This could involve scanning for vulnerabilities, researching potential entry points, and identifying potential targets within the organization.

- Initial Intrusion: Once the attacker has gathered enough information, they attempt to breach the target system or network. This could involve exploiting vulnerabilities in software or systems, utilizing social engineering techniques to trick users, or using other methods to gain initial access.

- Establish a Backdoor: After gaining initial access, the attacker often creates a backdoor or a persistent entry point into the compromised system. This ensures that even if the initial breach is discovered and mitigated, the attacker can still regain access.

- Obtain User Credentials: With a foothold in the system, the attacker may attempt to steal user credentials. This can involve techniques like keylogging, phishing, or exploiting weak authentication mechanisms.

- Install Various Utilities: Attackers may install various tools, utilities, or malware on the compromised system to facilitate further movement, data collection, or control. These tools could include remote access Trojans (RATs), keyloggers, and other types of malicious software.

- Privilege Escalation / Lateral Movement / Data Exfiltration: Once inside the system, the attacker seeks to elevate their privileges to gain more control over the network. They might move laterally within the network, trying to access more valuable systems or sensitive data. Data exfiltration involves stealing and transmitting valuable information out of the network.

- Maintain Persistence: This stage emphasizes the attacker's goal to maintain a long-term presence within the compromised environment. They do this by continuously evading detection, updating their tools, and adapting to any security measures put in place.

Critiques[edit]

Among the critiques of Lockheed Martin's cyber kill chain model as threat assessment and prevention tool is that the first phases happen outside the defended network, making it difficult to identify or defend against actions in these phases.[11] Similarly, this methodology is said to reinforce traditional perimeter-based and malware-prevention based defensive strategies.[12] Others have noted that the traditional cyber kill chain isn't suitable to model the insider threat.[13] This is particularly troublesome given the likelihood of successful attacks that breach the internal network perimeter, which is why organizations "need to develop a strategy for dealing with attackers inside the firewall. They need to think of every attacker as [a] potential insider".[14]

Unified kill chain[edit]

The Unified Kill Chain was developed in 2017 by Paul Pols in collaboration with Fox-IT and Leiden University to overcome common critiques against the traditional cyber kill chain, by uniting and extending Lockheed Martin's kill chain and MITRE's ATT&CK framework (both of which are based on the "Get In, Stay In, and Act" model constructed by James Tubberville and Joe Vest). The unified version of the kill chain is an ordered arrangement of 18 unique attack phases that may occur in end-to-end cyberattack, which covers activities that occur outside and within the defended network. As such, the unified kill chain improves over the scope limitations of the traditional kill chain and the time-agnostic nature of tactics in MITRE's ATT&CK. The unified model can be used to analyze, compare, and defend against end-to-end cyber attacks by advanced persistent threats (APTs).[15] A subsequent whitepaper on the unified kill chain was published in 2021.[16]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "U.S. Senate-Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation-A "Kill Chain" Analysis of the 2013 Target Data Breach-March 26, 2014" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2016.

- ^ Skopik & Pahi 2020, p. 4.

- ^ Higgins, Kelly Jackson (January 12, 2013). "How Lockheed Martin's 'Kill Chain' Stopped SecurID Attack". DARKReading. Archived from the original on 2024-01-19. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ Mason, Sean (December 2, 2014). "Leveraging The Kill Chain For Awesome". DARKReading. Archived from the original on 2024-01-19. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ Myers, Lysa (October 4, 2013). "The practicality of the Cyber Kill Chain approach to security". CSO Online. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ "Lockheed-Martin Corporation-Hutchins, Cloppert, and Amin-Intelligence-Driven Computer Network Defense Informed by Analysis of Adversary Campaigns and Intrusion Kill Chains-2011" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-07-27. Retrieved 2021-08-26.

- ^ Greene, Tim (5 August 2016). "Why the 'cyber kill chain' needs an upgrade". Archived from the original on 2023-01-20. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

- ^ "The Cyber Kill Chain or: how I learned to stop worrying and love data breaches". 2016-06-20. Archived from the original on 2016-09-18. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

- ^ John Franco. "Cyber Defense Overview: Attack Patterns" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-09-10. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- ^ Kim, Hyeob; Kwon, HyukJun; Kim, Kyung Kyu (February 2019). "Modified cyber kill chain model for multimedia service environments". Multimedia Tools and Applications. 78 (3): 3153–3170. doi:10.1007/s11042-018-5897-5. ISSN 1380-7501.

- ^ Laliberte, Marc (September 21, 2016). "A Twist On The Cyber Kill Chain: Defending Against A JavaScript Malware Attack". DARKReading. Archived from the original on 2023-12-13.

- ^ Engel, Giora (November 18, 2014). "Deconstructing The Cyber Kill Chain". DARKReading. Archived from the original on 2023-12-15. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ Reidy, Patrick. "Combating the Insider Threat at the FBI" (PDF). BlackHat USA 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-08-15. Retrieved 2018-10-15.

- ^ Devost, Matt (February 19, 2015). "Every Cyber Attacker is an Insider". OODA Loop. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ Pols, Paul (December 7, 2017). "The Unified Kill Chain" (PDF). Cyber Security Academy. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ Pols, Paul (May 17, 2021). "The Unified Kill Chain". UnifiedKillChain.com. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

Further reading[edit]

- Skopik, Florian; Pahi, Timea (2020). "Under false flag: using technical artifacts for cyber attack attribution". Cybersecurity. 3 (1): 8. doi:10.1186/s42400-020-00048-4. ISSN 2523-3246.