Antoine de Brichanteau

Antoine de Brichanteau | |

|---|---|

| Marquis de Beauvais-Nangis | |

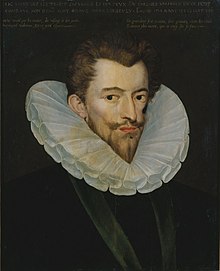

Sketch of Beauvais-Nangis | |

| Born | c. 1552 |

| Died | c. 1617 |

| Noble family | House of Brichanteau |

| Spouse(s) | Françoise de La Rochefoucauld |

| Issue | Nicolas II de Brichanteau |

| Father | Nicolas de Brichanteau |

| Mother | Jeanne d'Aguerre |

Antoine de Brichanteau, Marquis de Beauvais-Nangis (c. 1552 –c. 1617) was a French noble, military commander, and royal favourite during the French Wars of Religion and early-17th century. Born into a noble Briard family, Beauvais-Nangis began his military career at a young age, serving during the third French War of Religion at Jarnac and Moncontour, among other engagements. At the former, his valour was recognised by the brother of the king, Anjou, who took him into his household. He fought at the famous Siege of La Rochelle in 1573 and joined Anjou in the Commonwealth when he was elected as king. Upon Anjou's return to France as King Henri III, Beauvais-Nangis was elevated as commander of the Picard regiments during the fifth War of Religion. In November of that year, he was granted the prestigious role of Maître de camp of the French Guard. In the sixth civil war, he fought at the siege of Hiers-Brouage. In 1579, he was dispatched on a diplomatic mission to Portugal. By his return, however, his relations were becoming increasingly frayed with the king. He had repeatedly found himself in dispute with other favourites of the king, and resented his lack of financial compensation for the diplomatic mission. In 1581, he embarrassed the king in a confrontation he undertook with Henri's brother Alençon, in which he killed several of the duke's men. Henri felt obliged to disgrace him, and in March of that year, he was relieved of the post of Maître de camp. He spent the next several years aggrieved on his estates in Brie.

In 1584, the king's brother Alençon died, and with the heir to the throne now the Protestant Navarre, a Catholic ligue formed in opposition. Beauvais-Nangis was recruited into this with the promise that he would receive the office of colonel-eneral of the infantry, which he resented the royal favourite Épernon for having received. In March 1585, the ligue entered war with the crown and secured a favourable settlement in July of that year. Beauvais-Nangis was already disillusioned with the ligue which had failed to deliver him the office he desired and was fairly easily brought back into the royal orbit. In 1587, he entered the royal council, and he participated in the royalist attempt to suppress the ligue in Paris, which resulted in humiliation for the king. His participation in the Estates General of 1588 was engineered by the king, who needed more loyalist representatives to combat the ligue. In December of that year, he was involved to some extent in the deliberations that resulted in the decision to assassinate the Duke of Guise. In the war with the ligue that followed the assassination, Beauvais-Nangis fought loyally for the king and was rewarded with the office of admiral in February 1589. He held that office until 1592, when he was relieved of it by Navarre, now styled Henri IV after the death of Henri III. In 1614, he again served as a representative for an Estates General, dying three years later.

Early life and family[edit]

Family[edit]

Antoine de Brichanteau was born in 1552 as the son of Nicolas de Brichanteau and Jeanne d'Aguerre.[1][2] His father was a client of the Lorraine family, serving as governor of the town of Guise in Picardie.[3] He served as a gentilhomme de la chambre and captain in the gendarmerie, dying in 1564. The family was from the Briard nobility, and had been attested to going back to the 14th century.[4] He inherited the lordships of Nangis and Guerey near Provins. In the former, he held the rights of high justice and was a direct vassal of the king; in the latter, he held rents of justice.[5]

His nephew Jacques de La Fin would be a favourite and agent of Henri III's brother Alençon.[6] His sister Françoise de Brichanteau married the prominent ligueur Marquis de Vitry in 1580, while his other sister Marie de Brichanteau would marry the ligueur Baron de Sennecey in 1571, who would recruit Beauvais-Nangis into the ligue after his disgrace.[3]

Marriage[edit]

On 18 February 1577, Beauvais-Nangis secured an advantageous marriage to Antoinette de La Rochefoucauld, the daughter of Charles de La Rochefoucauld and Françoise Chabot, two important families in Bourgogne. She brought with her to the marriage a dowry of 30,000 livres and the barony of Liniėres in Berry, which was worth around 100,000 livres. In the coming years, her barony would become one of their primary residences.[7]

His son Nicolas de Brichanteau would succeed him as Marquis of Beauvais-Nangis.[8]

Youth[edit]

In his youth, Beauvais-Nangis completed his studies at the Collège de Lisieux in 1564 before entering the Paris Academy to learn how to fight.[5] At this time, he was under the protection of Marshal D'Aumont. D'Aumont occupied a relatively independent position in the court, propped up by the esteem for his long service and military experience.[9] In 1568, Beauvais-Nangis was dispatched by his mother to join the army of the Duke of Anjou.[5]

Unlike many favourites of Henri III, Beauvais-Nangis would not purchase a hôtel in Paris, and would content himself to rent an apartment in the hôtel of the Parlementaire Michel Le Tellier, near the Place Maubert. Le Tellier also served as his private attorney.[10]

Reign of Charles IX[edit]

Early service[edit]

Beauvais-Nangis began his service with the brother of the king and lieutenant-general of the army Anjou at a young age. From 1568, when he was only 16, he accompanied Anjou in his campaigns during the Third War of Religion. He also participated in the Battle of Jazaneuil and Pamprou in that year. On 11 March 1569, two days after participating in the Battle of Jarnac, Anjou named him a gentilhomme de la chambre, impressed by what he had seen on the field. He would bond with other future favourites of Anjou in this role, among them Joachim de Châteauvieux and René de Villequier. He served then as a guidon in an ordinance company for the Duke of Angoulême, an illegitimate son of Henri II, seeing service at the decisive royal victory of Moncontour the following year.[5] In the wake of this victory, the royal army became bogged down in the Siege of Saint-Jean-d'Angély where Beauvais-Nangis also saw combat.[11]

Alongside serving the Duke of Anjou as gentilhomme de la chambre, he would also hold the role of chambellan for the prince.[12] In 1571, he joined his first crusade against the Devlet-i ʿAlīye-i ʿOsmānīye with the Duke of Mayenne.[2]

La Rochelle[edit]

In response to the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew, the Protestant-dominated city of La Rochelle entered rebellion against the crown. The brother to the king, Anjou, was dispatched to lead the effort to reduce the city.[13] Joining him on the siege lines would be many young nobles eager to prove themselves militarily, among them Beauvais-Nangis.[14] The siege would drag on, before Anjou's election as king of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth allowed him to bring it to a close by negotiated settlement.[15]

Commonwealth[edit]

Beauvais-Nangis was among the French nobles who served Anjou during his reign on the Commonwealth.[16] Anjou was displeased that Beauvais-Nangis departed from him for a second time to crusade against the Devlet-i ʿAlīye-i ʿOsmānīye along with the Duke of Mayenne and Jean de Saulx, criticising their behaviour.[17]

Anjou resolved to flee the Commonwealth, to return to his home country and establish himself as King of France. To this end, on 18 June, he fled from his chambers on horseback at night. He was accompanied by several loyal servants, and they rode to Oświęcim, where they rendezvoused with Pibrac, Villequier, Caylus, and Beauvais-Nangis. The combined group then continued their flight into Austria.[18]

Reign of Henri III[edit]

Upon Anjou's return to France, now as Henri III, the grandee Duke of Nevers felt marginalised in the new court. He bemoaned the betrayal of men who had demonstrated more loyalty to Marshal Bellegarde than him and drew up a list of those upon whom he felt he could rely for political support. Among those names were La Rocheguyon, Schomberg, Malicorne, and Beauvais-Nangis.[19]

Picard regiment[edit]

The young noble would receive important military command during the Fifth War of Religion, receiving leadership of the Picard regiments on 30 June 1575. With this appointment, he departed from his role in the company of Angoulême as guidon.[20] In November of that year, the Maître de camp of the French guard, a very prestigious military post, was vacated by the murder of its incumbent Du Guast. The King of Navarre demanded that a man of his suite, Lavardin fill the office; however, Henri was keen to invest the post in a man who had been loyal to him before his rise to power as king and chose to grant it to Beauvais-Nangis.[21]

Beauvais-Nangis was established as a gentilhomme de la chambre du roi. He would, however, refuse take the oath required for the role at the hands of François d'O, the premier gentilhomme de la chambre, greatly disliking this favourite of Henri.[22]

Chevalier[edit]

During the reign of Henri, the creation of new chevaliers of the Ordre de Saint-Michel largely ceased. However, he occasionally continued to bestow the honour on his favourites. As such, in 1577, the honour went to the Comte de Brienne and Beauvais-Nangis.[23] During the sixth civil war in 1577, Beauvais-Nangis entered dispute with another favourite of the king, Saint-Luc. Beauvais-Nangis was very reluctant to hand over the command of the Picard regiments to Saint-Luc. He stalled the handover as much as he could, maintaining the command of the regiments during the siege of Brouage in the summer of that year.[22][24] During the Brouage siege, two favourites of Henri—La Guiche and the Comte de Caylus—were captured by a Protestant commander. The men looked to Beauvais-Nangis to secure their release, however he was unable to do so, and they remained in captivity until peace was made three months later.[25] Saint-Luc eventually gave up on acquiring the troops from Beauvais-Nangis and sold the rights to lead the company to Beauvais-Nangis, using the sum he raised from the sale to aid in his purchase of the government of Brouage.[26]

In early 1578, he fell out with Caylus, who was presently chief in the favour of the king. Caylus was pursuing a dispute with the Seigneur de Bussy, paramount favourite of the king's brother Alençon, and brought to bear many other of Henri's favourites for the purpose of confrontations with Bussy. However, Beauvais-Nangis refused to participate in the campaign against Bussy.[22][27][28]

By 1580, Beauvais-Nangis would no longer hold the office of écuyer that he had enjoyed in prior years.[29]

La Fère[edit]

During 1580, the Prince of Condé seized the important border town of La Fère hoping to advance his position. The crown responded by ordering the city be put to siege. The siege was led by Marshal Matignon. Matignon granted the royal favourite Épernon the honour of situating his troops right alongside the Champagne regiments right up against the city. Beauvais-Nangis was incensed by this as the honour of such a position theoretically belonged to the guards regiment, of which he was the Maître de camp. In an act of insubordination, he situated his troops right in front of the city.[22][30]

Beauvais-Nangis was not blind to the delicate situation he had manoeuvred himself into. When his father-in-law Barbezieux, the lieutenant-general of Champagne sought to resign his charge to Beauvais-Nangis, the young favourite refused the post, fearful that, if he were away from the king, his disgrace would become inevitable.[3] The charge was instead granted to another favourite: Joachim de Dinteville.[31]

Colonel-General[edit]

Relations between Beauvais-Nangis and the king increasingly reached a breaking point as Beauvais-Nangis pressed his claims to the office of colonel general of the French infantry, which was given to Épernon.[22] According to Beauvais-Nangis, the king had promised him the office before he departed on his diplomatic mission to Lisboa in February 1579 (the promise was made back in 1574 while in the Commonwealth) only to find the office in Épernon's hands upon his return.[3] He also complained that the king had not compensated him for the considerable personal expense he had accrued in his extraordinary diplomatic mission.[32][33] This was not false; the expedition had cost him 36,000 livres, and he had only been recompensed for 12,000 livres of that sum by the crown.[3] Accompanying him on the mission had been Urbain de Saint-Gelais, who would become a prominent ligueur in the years to follow.[3]

According to Brantôme, Beauvais-Nangis shouted to Épernon that he would never obey his orders as colonel-general.[34] The quarrel between the two men was noted by the English ambassador in February 1581.[35]

Alençon[edit]

The king's brother Alençon was increasingly set on his Dutch ambitions, and to that end raised troops during June 1581 for the purpose of entering Nederland. Henri charged Beauvais-Nangis with clearing Alençon's soldiers from the region surrounding Blois, where they were living off the land. He took his guards regiment to the area, where the soldiers ended up in a fight with an ordinance company belonging to Alençon. During the fight, several horseman of Alençon's were killed. Alençon was furious when he found out what had transpired, and demanded reparations from the king. Beauvais-Nangis defended himself as having acted upon the orders of the king, and wrote a letter defending himself. Henri was displeased by how public Beauvais-Nangis made the affair.[22][36]

Disgrace[edit]

After these episodes, Beauvais-Nangis was disgraced. According to the memoires later written by his son, he was stoic in his loss of favour, much to the annoyance of the king's other favourites. He retired to his estates in Brie.[34]

No longer in the king's favour, he could not be trusted to maintain his responsibilities as Maître de camp of the French guard, and in February 1582, he was relieved of the office in favour of Crillon.[21] Even in disgrace, removal of such a charge required compensation. In the memoires produced by his son, he claims that he was offered 60,000 livres and the governate of Metz, but refused them.[35]

From his family lands in Brie, he reconnected with his nexus of family allies, La Châtre, and his brothers-in-law the Marquis de Vitry and the Baron de Sennecey. Many nobles who were equally set in their hatred of Épernon visited him there.[37] Initially, though, he did not affiliate with any wider conspiratorial movements.[37]

Ligue crisis[edit]

In June 1584, the king's brother Alençon died, and as Henri did not have any children, the succession defaulted to his distant cousin, the Protestant Navarre. This was seized upon as a pretext by the Duke of Guise and allied Catholic nobles to refound the Catholic ligue in opposition to Navarre's succession, the favourites Henri surrounded himself with, and the failures to prosecute a war against 'heresy.' [38] It was to the end of joining this ligue that Beauvais-Nangis was approached by de Rosne and Sennecey, in their capacity as members of the Lorraine network. They promised him that if he defected to the orbit of the Duke of Guise, the duke would secure for him the post of colonel-general.[32]

Beauvais-Nangis aligned himself with the Duke of Guise and the ligue in 1585, more out of his hatred for Épernon than any particular affection for the Duke of Guise or the religious cause.[8][37] During his time of loyalty to the ligue, he enjoyed the tacit support of the Grand Prévôt Richilieu.[37] In March of that year, military operations against the crown commenced with Guise's seizure of Châlons. Beauvais-Nangis was not impressed by the campaign that followed, describing the duke's situation as embarrassing.[39] Upon arriving in Châlons himself, Beauvais-Nangis was disgusted to learn that the charge of colonel-general had already been promised by the Duke of Guise to another three men.[40] Feeling betrayed by Guise, he resolved to retreat from his loyalty to the ligue, though in a gradual fashion so as not to be accused of frivolity.[41] Nevertheless, the king capitulated to many of the demands of the ligue on 7 July in the Treaty of Nemours. Toleration of Protestantism was revoked, Navarre was excluded from the succession and surety towns were granted to the leading ligueurs.[42] Beauvais-Nangis would later opine that Henri missed the opportunity afforded to him by Guise's revolt to crush him.[43]

Loyalist[edit]

Beauvais-Nangis would be one of the nobles detached from loyalty to the ligue in 1586, alongside Entragues, d'O and the Duke of Nevers, who was secured for the crown by Catherine de' Medici.[44] Recalled by Henri, Beauvais-Nangis was able to appreciate that he had returned to the good graces of the king when Henri began to joke with him as he had in prior years.[45]

As a reward for his return to the royal orbit, he was elevated to a member of the royal council in 1587.[37] La Guiche was tasked by the king with the difficult task of reconciling Beauvais-Nangis and Épernon.[46]

During the Day of the Barricades, in which the king attempted a showdown with the ligue elements of the city and the Duke of Guise, Beauvais-Nangis commanded parts of the royal forces that were brought into the city.[37] In particular, Beauvais-Nangis was responsible for three companies of Swiss and two guard companies at the cemetery of the innocents. The forces would meet bitter opposition from Parisian ligueurs who successfully drove them from the streets and threatened to capture the king in response. Henri fled the city and made concessions to the ligueur-controlled Paris to subdue the capital.[47]

Estates General of 1588[edit]

The elections to the Estates General of 1588 would be unusually competitive. Henri competed with the leaders of the ligue to stack the Estates with as many delegates who he could trust to be loyal to his interests as possible. To this end, Henri put his thumb on the scales in Chartres to secure the election of his favourite Maintenon for the Second Estate. In Melun, he assisted in the selection of Beauvais-Nangis for the nobility. Despite these limited royalist successes, the Estates would be largely ligueur in composition.[48]

As the Estates General continued, Henri began to become increasingly frustrated with the Duke of Guise's dealings with the Third Estate, which he assumed were the cause of the Estates obstinacy in opposing him. In early December, Beauvais-Nangis, in his capacity as a noble deputy, came to Guise and warned him that the king was becoming jealous of the secret meetings held between Guise and the leaders of the Estate in his chambers each evening, during which strategy was debated.[49]

Assassination of the Duke of Guise[edit]

At a breaking point by mid December, Henri resolved on the need to deal with the Duke of Guise. To this end, he assembled a small council of himself, Alphonse d'Ornano, Rambouillet, and Maintenon, and it was agreed to assassinate the Duke of Guise by 3 votes to 1. According to the later memoire written by his son, having resolved on this, Henri turned to the 'wisest' of his advisers, Beauvais-Nangis, who advised him to again convene a council composed of the Angennes brothers, Marshal Aumont, and himself.[50] Henri complied and the following day the meeting was convened, with Beauvais-Nangis invited to speak first. Beauvais-Nangis outlined the terrible consequences that would follow from assassinating the duke with cities across France defecting from the crown. Beauvais-Nangis was instead to have proposed arresting the duke and putting him on trial in prison, with his execution only coming after a trial. Historians have raised a degree of scepticism about this account of Beauvais-Nangis' role, seeing in it a desire to aggrandise his foresight and importance with the benefit of hindsight concerning what would actually follow the assassination.[51]

In early 1589, with Henri now at war with the ligue again, he found himself at odds with his former-favourite Épernon. Épernon was frustrated that he had not been restored to the offices of admiral and colonel-general that were deprived to him as a result of his disgrace the prior year. The Estates General, which was finishing its deliberations, ruled that the office could not be kept in the Nogaret family through the Seigneur de La Valette who would thus have to resign the charge. Henri, for his part, angered Épernon further by responding to this through awarding the office of admiral to one of his enemies, Beauvais-Nangis.[52] Beauvais-Nangis would remain Admiral until 1592, when the office was granted to the Duc de Biron.[53]

During 1589, he would resist the calls of the ligue to again fight against Henri as he had in 1585. This was despite personal solicitations from the Duke of Mayenne, lieutenant-general of the ligue.[37]

Reign of Henri IV[edit]

In 1595, Beauvais-Nangis received the honour of being made a chevalier of the Ordre du Saint-Esprit, meaning that he was now in receipt of both orders of the king.[54]

Reign of Louis XIII[edit]

Beauvais-Nangis again served as a deputy from Melun for the Estates General of 1614. This made him one of only a small handful of deputies at the Estates General who had served in a prior Estates General. In total, five of the noble deputies present have been identified as having served in 1588.[55] One of his sons, a bishop, served in the First Estate.[56]

During the reign of Louis XIII, he served as a captain of 50 men-at-arms in the king's ordinance company.[54] He died in 1617.[57]

Sources[edit]

- Carroll, Stuart (2011). Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Chevallier, Pierre (1985). Henri III: Roi Shakespearien. Fayard.

- Constant, Jean-Marie (1984). Les Guise. Hachette.

- Constant, Jean-Marie (1996). La Ligue. Fayard.

- Hayden, J. Michael (1974). France and the Estates General of 1614. Cambridge University Press.

- Jouanna, Arlette (1998). Histoire et Dictionnaire des Guerres de Religion. Bouquins.

- Knecht, Robert (2016). Hero or Tyrant? Henry III, King of France, 1574-1589. Routledge.

- Le Roux, Nicolas (2000). La Faveur du Roi: Mignons et Courtisans au Temps des Derniers Valois. Champ Vallon.

- Le Roux, Nicolas (2006). Un Régicide au nom de Dieu: L'Assassinat d'Henri III. Gallimard.

- Le Roux, Nicolas (2020). Portraits d'un Royaume: Henri III, la Noblesse et la Ligue. Passés Composés.

- Salmon, J.H.M (1979). Society in Crisis: France during the Sixteenth Century. Metheun & Co.

References[edit]

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 258.

- ^ a b Le Roux 2000, p. 429.

- ^ a b c d e f Le Roux 2000, p. 430.

- ^ Le Roux 2020, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d Le Roux 2000, p. 261.

- ^ Le Roux 2020, p. 105.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 239.

- ^ a b Le Roux 2020, p. 133.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 259.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 295.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 132.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 145.

- ^ Knecht 2016, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Knecht 2016, p. 61.

- ^ Knecht 2016, p. 64.

- ^ Constant 1984, p. 96.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 156.

- ^ Knecht 2016, p. 83.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 168.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 315.

- ^ a b Le Roux 2000, p. 191.

- ^ a b c d e f Le Roux 2020, p. 83.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 201.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 317.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 318.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 332.

- ^ Chevallier 1985, p. 426.

- ^ Salmon 1979, p. 199.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 172.

- ^ Salmon 1979, p. 204.

- ^ Chevallier 1985, p. 427.

- ^ a b Constant 1984, p. 122.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 262.

- ^ a b Le Roux 2020, p. 84.

- ^ a b Le Roux 2000, p. 431.

- ^ Jouanna 1998, p. 1248.

- ^ a b c d e f g Le Roux 2000, p. 432.

- ^ Knecht 2016, pp. 229–231.

- ^ Constant 1984, p. 130.

- ^ Constant 1996, p. 133.

- ^ Constant 1984, p. 146.

- ^ Constant 1984, p. 135.

- ^ Constant 1984, p. 140.

- ^ Knecht 2016, p. 239.

- ^ Chevallier 1985, p. 387.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 687.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 677.

- ^ Jouanna 1998, p. 342.

- ^ Carroll 2011, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Constant 1984, p. 17.

- ^ Constant 1984, p. 18.

- ^ Le Roux 2006, p. 232.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 530.

- ^ a b Hayden 1974, p. 252.

- ^ Hayden 1974, p. 88.

- ^ Hayden 1974, p. 96.

- ^ Jouanna 1998, p. 1482.