User:Talpedia/Court system of England And Wales

The court systems provides a means for individuals to resolve disputes between one another; for the state to impose criminal punishments upon people who breach societal norms; and for individuals to resolve disputes with the state.

Cases are brought to a court where the court makes a judgement, these judgements are then enforced by the police, possibly after an application for an injunctions and a contempt of court case.

If either party in a case feels that error in reasoning has been made by the court, the may apply to a court of appeal for a ruling on this ruling. This has a few different functions, the judges in the court appeal may be more specialised, if precedent is being set more attention should be paid to the case. The rulings of a court of appeal are more likely to be reported than lower courts.

Slightly different rules apply to cases where the court can order some form of punishment (criminal law), and those where the court orders one party to do something to recompense another party for their loss (civil law). The rules for resolving a specific with the state or an instrument of the state (administrative law) are markedly different and will vary greatly depending on the nature of the dispute.

Civil cases[edit]

The law provides legal remedies to individuals. If one party (the claimant) can convince the court that certain conditions are met then the court will compel the other party (the defendant) to do certain things, most often pay the defendant some money.

Whether these conditions are satisfied is normally resolved at a trial, the claimaint will follow a procedure set out by court to apply for a trial and if the court is satisfied that a trial is necessary (cause of action) then the court will arrange a date for the trial, giving the defendant the opportunity to disprove and evidence presented by the claimant. There is often a process of discovery whereby the parties have to provide each other with details of the arguments that they are going to make ahead of time, in an attempt to make the trial fairer.

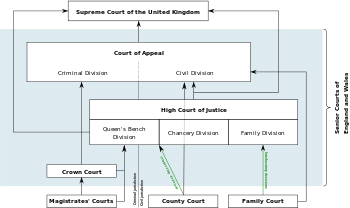

A set of rules, the Civil Procedure Rules govern this process. There are different types of court for different types of cases, common cases involving small sums of money are resolved by County Courts. Cases involving larger sums are resolved by the High Court, which has divisions specialising in different fields.

Criminal cases[edit]

In theory, any party can apply to a court for a criminal case (a private prosecution). However, there is a privileged body, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), that in practice applies to a court for most criminal cases and able to take over the case, and possibly discontinue it. [1]The CPS, provides an appeals process if someone feels they were wrong in not prosecuting a case.

The rules governing criminal cases are the Criminal Procedure Rules. [2]

Tribunals[edit]

There are a variety of special purpose courts, with idiosyncratic procedures and rules that deal with administrative law. Common examples include, Employment tribunals and the Planning Inspectorate.

There has been some attempt to make these tribunals, more consistent. the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 created a new unified structure for tribunals and created two new tribunals: the First-tier Tribunal and an Upper Tribunal, where disputes from specific tribunals are referred. There is a right of appeal to the Court of Appeal of England and Wales on points of law.

Subordinate courts[edit]

The most common subordinate courts in England and Wales, where cases tend to begin are, are the

Criminal cases[edit]

There are two kinds of criminal trial: 'summary' and 'on indictment'. For an adult, summary trials take place in a magistrates' court, while trials on indictment take place in the Crown Court. Despite the possibility of two venues for trial, almost all criminal cases, however serious, commence in the Magistrates' Courts. It is possible to start a trial for an indictable offence by a voluntary bill of indictment, and go directly to the Crown Court, but that would be unusual.

A criminal case that starts in the Magistrates' Court may begin either by the defendant being charged and then being brought forcibly before Magistrates, or by summons to the defendant to appear on a certain day before the Magistrates. A summons is usually confined to very minor offences. The hearing (of the charge or summons) before the Magistrates is known as a "first appearance".

Offences are of three categories: indictable only, summary and either way. Indictable only offences such as murder and rape must be tried on indictment in the Crown Court. On first appearance, the Magistrates must immediately refer the defendant to the Crown Court for trial, their only role being to decide whether to remand the defendant on bail or in custody.

Summary offences, such as most motoring offences, carry lower penalties and most must be tried in the Magistrates' Court, although a few may be sent for trial to the Crown Court along with other offences that may be tried there (for example assault). The vast majority of offences are also concluded in a magistrates' court (over 90% of cases).

Either way offences are intermediate offences such as theft and, with the exception of low value criminal damage, may be tried either summarily (by magistrates) or by judge and jury in the Crown Court. If the magistrates consider that an either way offence is too serious for them to deal with, they may "decline jurisdiction" which means that the defendant will have to appear in the Crown Court. Conversely even if the magistrates accept jurisdiction, an adult defendant has a right to compel a jury trial. Defendants under 18 years of age do not have this right and will be tried in the youth court (similar to a magistrates' court) unless the case is homicide or else is particularly serious.

A magistrates' court is made up in two ways. Either a group (known as a 'bench') of 'lay magistrates', or a district judge, will hear the case. A lay bench must consist of at least three magistrates. Alternatively a case may be heard by a district judge (formerly known as a stipendiary magistrate), who will be a qualified lawyer and will sit singly, but has the same powers as a lay bench. District judges usually sit in the more busy courts in cities or hear complex cases (e.g. extradition). Magistrates have limited sentencing powers.

In the Crown Court, the case is tried before a Recorder (part-time judge), Circuit Judge or a High Court judge, and a jury. The seniority of the judge depends on the seriousness and complexity of the case. The jury is involved only if the defendant enters a plea of "not guilty".

Civil cases[edit]

Before starting a civil case a claimant is required to identify what legislation or common law the believe applies, and estimate how much money (if any) they can claim from the defendant.

Under the Civil Procedure Rules 1998, civil claims under £10,000 are dealt with in a county court under the 'small claims track'. This is generally known to the lay public as 'small claims court' but does not exist as a separate court. Claims between £10,000 and £25,000 that are capable of being tried within one day are allocated to the 'fast track' and claims over £25,000 to the 'multi track'. These 'tracks' are labels for the use of the court system – the actual cases will be heard in a county court or the High Court depending on their value.

For personal injury, defamation cases and in some landlord and tenant disputes the thresholds for each track have different values.

Appeals[edit]

From the magistrates' courts, an appeal can be taken to the Crown Court on matters of fact and law or, on matters of law alone, to the Administrative Court of Queen's Bench Division of the High Court, which is called an appeal "by way of case stated". The Magistrates' Court is also an inferior court and is therefore subject to judicial review.

The Crown Court is more complicated. When it is hearing a trial on indictment (a jury trial) it is treated as a superior court, which means that its decisions may not be judicially reviewed and appeal lies only to the Criminal Division of the Court of Appeal.

In other circumstances (for example when acting as an appeal court from a Magistrates' Court) the Crown Court is an inferior court, which means that it is subject to judicial review. When acting as an inferior court, appeals by way of case stated on matters of law may be made to the Administrative Court.

Appeals from the High Court, in criminal matters, lie only to the Supreme Court. Appeals from the Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) may also only be taken to the Supreme Court.

Appeals to the Supreme Court are unusual in that the court from which appeal is being made (either the High Court or the Court of Appeal) must certify that there is a point of law of general public importance. This additional control mechanism is not present with civil appeals and means that far fewer criminal appeals are heard by the Supreme Court.

International relationships[edit]

Relationship with the European Court of Justice[edit]

The European Court of Justice acts only as a supreme court for the interpretation of European Union law. Consequently, there is no right to appeal at any stage in UK court proceedings to the ECJ. However, any court in the UK may refer a particular point of law relating to European Union law to the ECJ for determination. However, once the ECJ has given its interpretation, the case is referred back to the court that referred it.

The decision to refer a question to the ECJ can be made by the court of its own initiative, or at the request of any of the parties before it. Where a question of European law is in doubt and there is no appeal from the decision of a court, it is required (except under the doctrine of acte clair) to refer the question to the ECJ; otherwise any referral is entirely at the discretion of the court.

Relationship with the European Court of Human Rights[edit]

It is not possible to appeal the decision of any court in England and Wales to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). Although it is frequent to hear media references to an "appeal" being taken "to Europe", what actually takes place is rather different.

The ECtHR is an international court that hears complaints concerning breaches of the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. An unsatisfied litigant in England and Wales might complain to the ECtHR that English law has violated his rights. A decision in the ECtHR will not change English law, and it is up to the Government of the United Kingdom to decide what action (if any) to take after an adverse finding.

Courts in England and Wales are not bound to follow a decision of the ECtHR, although they should "take into account" ECtHR jurisprudence when applying the Convention. The Convention has always had an influence on decisions of courts in England and Wales, but now the Convention has two further effects:

- a court, being a public body, must act in accordance with the Convention Rights found in the Human Rights Act 1998, which includes a requirement to construe statutes in accordance with the Convention; and

- direct claims may be made under the Human Rights Act 1998 against a public body for breach of Convention rights.

Relationship with the International Criminal Court[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

- ^ "Prosecution of Offences Act 1985". 1985-05-23. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- ^ "Criminal Procedure Rules". Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 2016-10-18.