User:SomeGuyWhoRandomlyEdits/Old Elamite period

Old Elamite Period | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| circa 2700 BCE — circa 1500 BCE | |||||||||||

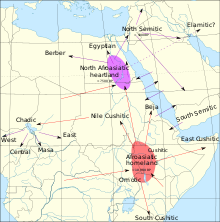

Map of Elam (approximate extension of the Elamite Empire is shown in red, the size of the Persian Gulf in the Bronze Age is indicated in blue (violet?)) | |||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||

| Common languages | Elamite language | ||||||||||

| Religion | Matriarchal religion | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King of Elam | |||||||||||

• circa 2700 — 2680 BCE | Humbaba (first) | ||||||||||

• circa 1500 BCE | Kutik-Matlat (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||||

• Established | circa 2700 BCE | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | circa 1500 BCE | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

| History of Iran |

|---|

|

|

Timeline |

The Old Elamite period began around 2700 BC. Historical records mention the conquest of Elam by Enmebaragesi the Sumerian king of Kish in Mesopotamia. Three dynasties ruled during this period. We know of twelve kings of each of the first two dynasties, those of Awan (or Avan; c. 2400–2100 BC) and Simash (c. 2100–1970 BC), from a list from Susa dating to the Old Babylonian period. Two Elamite dynasties said to have exercised brief control over parts of Sumer in very early times include Awan and Hamazi; and likewise, several of the stronger Sumerian rulers, such as Eannatum of Lagash and Lugal-anne-mundu of Adab, are recorded as temporarily dominating Elam.

The Avan dynasty was partly contemporary with that of the Mesopotamian emperor Sargon of Akkad, who not only defeated the Awan king Luhi-ishan and subjected Susa, but attempted to make Akkadian the official language there. From this time, Mesopotamian sources concerning Elam become more frequent, since the Mesopotamians had developed an interest in resources (such as wood, stone, and metal) from the Iranian plateau, and military expeditions to the area became more common. With the collapse of Akkad under Sargon's great great-grandson, Shar-kali-sharri, Elam declared independence under the last Avan king, Kutik-Inshushinak (c. 2240–2220 BC), and threw off the Akkadian language, promoting in its place the brief Linear Elamite script. Kutik-Inshushinnak conquered Susa and Anshan, and seems to have achieved some sort of political unity. Following his reign, the Awan dynasty collapsed as Elam was temporarily overrun by the Guti, a people from what is now north west Iran speaking a language isolate.

Origin of name[edit]

The Elamites called their country Haltamti,[1] Sumerian ELAM, Akkadian Elamû, female Elamītu "resident of Susiana, Elamite".[2]

The high country of Elam was increasingly identified by its low-lying later capital, Susa. Geographers after Ptolemy called it Susiana. The Elamite civilization was primarily centered in the province of what is modern-day Khuzestān and Ilam in prehistoric times. The modern provincial name Khuzestān is derived from the Persian name for Susa: Old Persian Hūjiya "Elam" (Old Persian: 𐎢𐎺𐎩),[1] in Middle Persian Huź "Susiana", which gave modern Persian Xuz, compounded with -stån "place" (cf. Sistan "Saka-land").

Ancient City-States in Iran[edit]

By circa 2600 BCE, Elam was divided into about four city-states. Each was centered on a temple dedicated to the particular patron god or goddess of the city and ruled over by a king who was intimately tied to the city's religious rites.

The four "first" cities said to have exercised kingship :

(1location uncertain)

History[edit]

Early Elamite kings[edit]

This is a list of early Elamite kings from the Old Elamite Period. All dates are middle chronology.

| Throne Name | Original Name | Portrait | Title | Born-Died | Entered office | Left office | Family Relations | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Humbaba | ?–c. 2680 BC | c. 2700 BC | c. 2680 BC | ? | contemporary with Gilgamesh king of Uruk | |||

| 2 | Humban-Shutur (or Khumbastir) | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | ||||

Awan dynasty[edit]

The Awan Dynasty was the first dynasty of Elam of which anything is known today, appearing at the dawn of historical record. The Elamites were likely major rivals of neighboring Sumer from remotest antiquity; they were said to have been defeated by Enmebaragesi of Kish (ca. 25th century BC), who is the earliest archaeologically attested Sumerian king, as well as by a later monarch, Eannatum I of Lagash.

Awan was a city or possibly a region of Elam whose precise location is not certain, but it has been variously conjectured to be north of Susa, in south Luristan, close to Dezful, or Godin Tepe.

Elam and Sumer[edit]

According to the Sumerian king list, a dynasty from Awan exerted hegemony in Sumer at one time. It mentions three Awan kings, who supposedly reigned for a total of 356 years.[3] Their names have not survived on the extant copies, apart from the partial name of the third king, "Ku-ul...", who it says ruled for 36 years.[4] This information is not considered reliable, but it does suggest that Awan had political importance in the 3rd millennium BC.

A royal list found at Susa gives 12 names of the kings in the Awan dynasty.[5] As there are very few other sources for this period, most of these names are not certain.

Little more of these kings' reigns is known, but Elam seems to have kept up a heavy trade with the Sumerian city-states during this time, importing mainly foods, and exporting cattle, wool, slaves and silver, among other things. A text of the time refers to a shipment of tin to the governor of the Elamite city of Urua, which was committed to work the material and return it in the form of bronze — perhaps indicating a technological edge enjoyed by the Elamites over the Sumerians.

It is also known that the Awan kings carried out incursions in Mesopotamia, where they ran up against the most powerful city-states of this period, Kish and Lagash. One such incident is recorded in a tablet addressed to Enetarzi, a minor ruler or governor of Lagash, testifying that a party of 600 Elamites had been intercepted and defeated while attempting to abscond from the port with plunder.

Events become a little clearer at the time of the Akkadian Empire (ca. 2300 BC), when historical texts tell of campaigns carried out by the kings of Akkad on the Iranian plateau. Sargon of Akkad boasted of defeating a "Luh-ishan king of Elam, son of Hishiprashini", and mentions plunder seized from Awan, among other places. Luhi-ishan is the eighth king on the Awan king-list, while his father's name "Hishiprashini" is a variant of that of the ninth listed king, Hishepratep - indicating either a different individual, or if the same, that the order of kings on the Awan king list has been jumbled.[4]

Sargon's son and successor, Rimush, is said to have conquered Elam, defeating its king who is named as Emahsini. Emahsini's name does not appear on the Awan kinglist, but the Rimush inscriptions claim that the combined forces of Elam and Warahshe, led by General Sidgau, were defeated at a battle "on the middle river between Awan and Susa". Scholars have adduced a number of such clues that Awan and Susa were probably adjoining territories.

With these defeats, the low-lying, westerly parts of Elam became a vassal of Akkad centred at Susa. This is confirmed by a document of great historical value, a peace treaty signed between Naram-Sin of Akkad and an unnamed king or governor of Awan, probably Khita or Helu. It is the oldest document written in Elamite cuneiform that has been found.

Although Awan was defeated, the Elamites were able to avoid total assimilation. The capital of Anshan, located in a steep and mountainous area, was never reached by Akkad. The Elamites remained a major source of tension, that would contribute to destabilizing the Akkadian state, until it finally collapsed under Gutian pressure.

Reign of Kutik-Inshushinak[edit]

Kutik-Inshushinak (also known as Puzur-Inshushinak) was king of Elam from about 2240 to 2220 BC (long chronology), and the last from the Awan dynasty.[6]

His father was Shinpi-khish-khuk, the crown prince, and most likely a brother of king Khita. Kutik-Inshushinak's first position was as governor of Susa, which he may have held from a young age. About 2250 BC, his father died, and he became crown prince in his stead.

Elam had been under the domination of Akkad since the time of Sargon, and Kutik-Inshushinak accordingly campaigned in the Zagros mountains on their behalf. He was greatly successful as his conquests seem to have gone beyond the initial mission.

In 2240 BC, he asserted his independence from Akkad, which had been weakening ever since the death of Naram-Sin, thus making himself king of Elam. He conquered Anshan and managed to unite most of Elam into one kingdom. He built extensively on the citadel at Susa, and encouraged the use of the Linear Elamite script to write the Elamite language. This may be seen as a reaction against Sargon's attempt to force the use of Akkadian. Most inscriptions in Linear Elamite date from the reign of Kutik-Inshushinak.

His achievements were not long-lasting, for after his death the linear script fell into disuse, and Susa was overrun by the Third dynasty of Ur, while Elam fell under control of Simashki dynasty (also Elamite origin).[7]

It is now known that his reign in Elam overlapped with that of Ur-Nammu of Ur-III,[8] although the previous lengthy estimates of the duration of the intervening Gutian dynasty and rule of Utu-hengal of Uruk had not allowed for that synchronism.

Postscript: Awan and Anshan?[edit]

The toponym "Awan" only occurs once more following the reign of Kutik-Inshushinak, in a year-name of Ibbi-Sin of Ur. The name Anshan, on the other hand, which only occurs once before this time (in an inscription of Manishtushu), becomes increasingly more commonplace beginning with king Gudea of Lagash, who claimed to have conquered it around the same time. It has accordingly been conjectured that Anshan not only replaced Awan as one of the major divisions of Elam, but that it also included the same territory.[9]

Awan kinglist[edit]

| Throne Name | Original Name | Portrait | Title | Born-Died | Entered office | Left office | Family Relations | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | The unnamed King of Awan | King of Awan | ?–? | c. 2580 BC | ? | ? | contemporary with the last king of the first dynasty of Uruk[10] | ||

| 4 | ...Lu | King of Awan | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | |||

| 5 | Kur-Ishshak | King of Awan | ?–? | ? | c. 2550 BC | ? | 36 years. contemporary with Lugal-Anne-Mundu king of Adab & Ur-Nanshe king of Lagash | ||

| 6 | Peli | King of Awan | ?–? | c. 2500 BC | ? | ? | |||

| 7 | Tata I | King of Awan | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | |||

| 8 | Ukku-Tanhish | King of Awan | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | |||

| 9 | Hishutash | King of Awan | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | |||

| 10 | Shushun-Tarana | King of Awan | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | |||

| 11 | Napi-Ilhush | King of Awan | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | |||

| 12 | Kikku-Siwe-Temti | King of Awan | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | |||

| 13 | Hishep-Ratep I | King of Awan | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | |||

| 14 | Luh-Ishshan | King of Awan | ?–c. 2325 BC | ? | c. 2325 BC | Son of Hishep-Ratep I | |||

| 15 | Hishep-Ratep II | King of Awan | ?–? | c. 2325 BC | ? | Son of Luh-Ishshan | |||

| 16 | Emahsini[11] | King of Awan | ?–2311 BC | c. 2315 BC | 2311 BC | ||||

| 17 | Helu | King of Awan | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | |||

| 18 | Hita | King of Awan | ?–? | c. 2270 BC | c. 2270 BC | ? | contemporary of Naram-Sin king of Akkad | ||

| 19 | Kutik-Inshushinak[12] | King of Awan | ?–? | c. 2100 BC | c. 2100 BC | son of Shinpi-hish-huk | contemporary of Ur-Nammu king of Ur. Susa conquered by Ur troops in 2078 and 2016 BC | ||

Simashki dynasty[edit]

Reign of Kindattu[edit]

The Sumerian king Shulgi of the Neo-Sumerian Empire took the city of Susa and the surrounding region. During the first part of the rule of the Simashki dynasty, Elam was under intermittent attack from Mesopotamians and also Gutians from northwestern Iran, alternating with periods of peace and diplomatic approaches. Shu-Sin of Ur, for example, gave one of his daughters in marriage to a prince of Anshan. But the power of the Sumerians was waning; Ibbi-Sin in the 21st century did not manage to penetrate far into Elam, and in 2004 BC, the Elamites, allied with the people of Susa and led by king Kindattu, the sixth king of Simashk, managed to sack Ur and lead Ibbi-Sin into captivity—thus ending the third dynasty of Ur. The Akkadian kings of Isin, successor state to Ur, did manage to drive the Elamites out of Ur, rebuild the city, and to return the statue of Nanna that the Elamites had plundered.

Lament for Ur[edit]

The Lament for Ur, or Lamentation over the city of Ur is a Sumerian lament composed around the time of the fall of Ur to the Elamites and the end of the city's third dynasty (c. 2000 BC).

Laments[edit]

It contains one of five known Mesopotamian "city laments"—dirges for ruined cities in the voice of the city's tutelary goddess.

The other city laments are:

- The Lament for Sumer and Ur

- The Lament for Nippur

- The Lament for Eridu

- The Lament for Uruk

The Book of Lamentations of the Old Testament, which bewails the destruction of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon in the sixth century B.C., is similar in style and theme to these earlier Mesopotamian laments. Similar laments can be found in the Book of Jeremiah, the Book of Ezekiel and the Book of Psalms, Psalm 137 (Psalms 137:1–9), a song covered by Boney M in 1978 as Rivers of Babylon.[13]

Compilation[edit]

The first lines of the lament were discovered on the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology catalogue of the Babylonian section, tablet numbers 2204, 2270, 2302 and 19751 from their excavations at the temple library at Nippur. These were translated by George Aaron Barton in 1918 and first published as "Sumerian religious texts" in Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions, number six, entitled "A prayer for the city of Ur".[14] The restored tablet is 9 by 4.5 by 1.75 inches (22.9 by 11.4 by 4.4 cm) at its thickest point. Barton noted that "from the portions that can be translated it appears to be a prayer for the city of Ur at a time of great danger and distress. It seems impossible to assign it with certainty to any particular period." He noted that it was plausible but unconfirmed to conjecture that it "was written in the last days of Ibbi-Sin when Ur was tottering to its fall".[14]

Edward Chiera published other tablets CBS 3878, 6889, 6905, 7975, 8079, 10227, 13911 and 14110 in "Sumerian texts of varied contents" in 1934, which combined with tablets CBS 3901, 3927, 8023, 9316, 11078 and 14234 to further restore the myth, calling it a "Lamentation over the city of Ur".[15] A further tablet source of the myth is held by the Louvre in Paris, number AO 6446.[16] Others are held in the Ashmolean, Oxford, numbers 1932,415, 1932,522, 1932,526j and 1932,526o.[17] Further tablets were found to be part of the myth in the Hilprecht collection at the University of Jena, Germany, numbers 1426, 1427, 1452, 1575, 1579, 1487, 1510 and 1553.[18] More fragments are held at the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire (Geneva) in Switzerland, MAH 15861 and MAH 16015.[19]

Other translations were made from tablets in the Nippur collection of the Museum of the Ancient Orient in Istanbul (Ni). Samuel Noah Kramer amongst others worked to translate several others from the Istanbul collection including Ni 4496, 1162, 2401, 2510, 2518, 2780, 2911, 3166, 4024, 4424, 4429, 4459, 4474, 4566, 9586, 9599, 9623, 9822 and 9969.[20][21] Other tablets from the Istanbul collection, numbers Ni 2510 and 2518 were translated by Edward Chiera in 1924 in "Sumerian religious texts".[22] Sir Charles Leonard Woolley unearthed more tablets at Ur contained in the "Ur excavations texts" from 1928.[23] Other tablets are held in the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin and the Yale Babylonian collection.[24] Samuel Noah Kramer compiled twenty-two different fragments into the first complete edition of the Lament, which was published in 1940 by the University of Chicago as Lamentation over the Destruction of Ur (Assyriological Study no. 12). Other tablets and versions were used to bring the myth to its present form with a composite text by Miguel Civil produced in 1989 and latest translations by Thorkild Jacobsen in 1987 and Joachim Krecher in 1996.[25][26]

Composition[edit]

The lament is composed of four hundred and thirty eight lines in eleven kirugu (sections), arranged in stanzas of six lines. It describes the goddess Ningal, who weeps for her city after pleading with the god Enlil to call back a destructive storm. Interspersed with the goddess's wailing are other sections, possibly of different origin and composition; these describe the ghost town that Ur has become, recount the wrath of Enlil's storm, and invoke the protection of the god Nanna (Nergal or Suen) against future calamities. Ningal, the wife of the moon god Nanna, goes on to recall her petition to the leaders of the gods, An and Enlil to change their minds and not to destroy Ur.[27] She does this both in private and in a speech to the Annanuki assembly:

| “ | I verily clasped legs, laid hold of arms, truly I shed my tears before An, truly I made supplication, I myself before Enlil: "May my city not be ravaged, I said to them, May Ur not be ravaged.[27] | ” |

The council of gods decide that the Ur III dynasty, which had reigned for around one hundred years, had its destiny apportioned to end. The temple treasury was raided by invading Elamites and the centre of power in Sumer moved to Isin, while control of trade in Ur passed to several leading families of the city. Kenneth Wade suggested that Terah, the father of Abraham in the Book of Genesis could have been one of the heads of such a leading family (Genesis 11:28).[28] The metaphor of a garden hut being knocked down is used for the destroyed temple of Ur and in subsequent lines this metaphorical language is extended to the rest of the setting, reminiscent of the representation of Jerusalem as a "booth" in the Book of Amos (Amos 9:11).[29] Ningal bewails:

| “ | My faithful house ... like a tent, a pulled-up harvest shed, like a pulled-up harvest shed! Ur, my home filled with things, my well-filled house and city that were pulled up, were verily pulled up.[29] | ” |

The different temples throughout the land are described with their patron gods or goddesses abandoning the temples, like sheepfolds:

| “ | Ninlil has abandoned that house, the Ki-ur, and has let the breezes haunt her sheepfold. The queen of Kesh has abandoned it and has let the breezes haunt her sheepfold. Ninmah has abandoned that house Kesh and has let the breezes haunt her sheepfold.[25] | ” |

Edward L. Greenstein has noted the emptying of sheep pens as a metaphor of the destruction of the city. He also notes that the speakers of the laments are generally male lamentation-priests, who take on the characteristics of a traditional female singer and ask for the gods to be appeased so the temples can be restored. Then a goddess, sometimes accompanied by a god notes the devastation and weeps bitterly with a dirge about the destructive storm and an entreats to the gods to return to the sanctuaries. The destruction of the Elamites is compared in the myth to imagery of a rising flood and raging storm. This imagery is facilitated by the title of Enlil as the "god of the winds"[30] The following text suggests that the setting of the myth was subject to a destructive storm prior to its final destruction:[31]

| “ | Alas, storm after storm swept the Land together: the great storm of heaven, the ever-roaring storm, the malicious storm which swept over the Land, the storm which destroyed cities, the storm which destroyed houses, the storm which destroyed cow-pens, the storm which burned sheepfolds, which laid hands on the holy rites, which defiled the weighty counsel, the storm which cut off all that is good from the Land.[25] | ” |

Various buildings are noted to be destroyed in Enlil's storm, including the shrines of Agrun-kug and Egal-mah, the Ekur (the sanctuary of Enlil), the Iri-kug, the Eridug and the Unug.[25] The destruction of the E-kic-nu-jal is described in detail.

| “ | The good house of the lofty untouchable mountain, E-kic-nu-jal, was entirely devoured by large axes. The people of Cimacki and Elam, the destroyers, counted its worth as only thirty shekels. They broke up the good house with pickaxes. They reduced the city to ruin mounds.[25] | ” |

Images of what was lost, and the scorched earth that was left behind indicate the scale of the catastrophe. The Line 274 reads

| “ | "eden kiri-zal bi du-du-a-mu gir-gin ha-ba-hu-hur" - My steppe, established for joy, was scorched like an oven.[32] | ” |

The destruction of the location is reported to Enlil, and his consort Ninlil, who are praised and exalted at the end of the myth.[33]

Discussion[edit]

The Lament for Ur has been well known to scholarship and well edited for a long time. Piotr Michalowski has suggested this gave literary primacy to the myth over the Lament for Sumer and Ur, originally called the "Second Lament for Ur", which he argues was chronologically a more archaic version.[32] Philip S. Alexander compares lines seventeen and eighteen of the myth with Lamentations 2:17 "The Lord has done what he purposed, he has carried out his threat; as he ordained long ago, he has demolished without pity", suggesting this could "allude to some mysterious, ineluctable fate ordained for Zion in the distant past":

| “ | The wild bull of Eridug has abandoned it and has let the breezes haunt his sheepfold. Enki has abandoned that house Eridug and has let the breezes haunt his sheepfold.[34] | ” |

The devastation of cities and settlements by natural disasters and invaders has been used widely throughout the history of literature since the end of the Third Dynasty of Ur. A stela (pictured) from Iraq depicts a similar destruction of a mountain house at Susa. The imagery of destruction and human loss in the Lament for Ur has been suggested to show similarities with the modern scenes reported in the present day Iraq (soldiers on the Ziggurat of Ur pictured), the Middle East and Africa.[35]

| “ | Dead men, not potsherds. Covered the approaches. The walls were gaping, the high gates, the roads, were piled with dead. In the side streets, where feasting crows would gather, scattered they lay. In all the side streets and roadways bodies lay. In the open fields that used to fill with dancers, they lay in heaps. The country's blood now filled its holes, like metal in a mould; Bodies dissolved - like fat left in the sun.[35] | ” |

Michelle Breyer suggested tribes of neighbouring shepherds destroyed the city and called Ur, "the last great city to fall".[36]

Reign of Chedorlaomer[edit]

| Chedorlaomer | |

|---|---|

| King of Elam | |

| House | Elam |

Chedorlaomer, also spelled Kedorlaomer (/ˌkɛdərˈleɪəmər/; Hebrew: כְּדָרְלָעֹ֫מֶר Kəḏārəlā‘ōmer, "a handful of sheaves"),[37] is a king of Elam in the book of Genesis Chapter 14.[38] He is recorded as, allied with three other kings,[39] campaigning against five city kingdoms in response to an uprising in the days of Abraham.

Etymology[edit]

The name Chedorlaomer is associated with familiar Elamite components, such as kudur, meaning “servant”, and Lagamar who was a high goddess in the Elamite pantheon.[40][41]

The linguistic origins of the name Chedorlaomer may be traced to Persian or Assyrian names. There is a linguistic agreement in the Persian pronunciation for Kĕdorla`omer, pronounced ked·or·lä·o'·mer. The association to Assyrian names are Kudurlagamar and Kudur-Mabuk, a ruler in Larsa from 1770 BCE to 1754 BCE.[42] However, the 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia stated that, apart from the fact that Chedorlaomer can be identified as a proper Elamite compound, "all else is matter of controversy" and "the records give only the rather negative result that from Babylonian and Elamite documents nothing definite has been learned of Chedorlaomer."[42]

Background[edit]

Chedorlaomer's reign[edit]

After twelve years of being under Elamite rule, in the thirteenth year, the Cities of the Plain rebelled against Chedorlaomer. This spurred a domino effect that prompted the Elamite king to regain control. To ensure his success, he called upon three other allies from Shinar, Ellasar, and Tidal "nations" regions. (Genesis 14:9)[43]

Chedorlaomer's allies[edit]

The following allies fought in every campaign under Chedorlaomer's direction, while in the fourteenth and final year of his rule.[44]

Chedorlaomer's campaigns[edit]

The purpose of Chedorlaomer's campaigns was to show Elam's might to all territories under Elamite authority. His armies and allies plundered tribes and cities, for their provisions, who were en route to the revolting cities of the Jordan plain.

- The Rephaims in Ashteroth Karnaim

- The Emims in Shaveh Kiriathaim

- The Horites in Mount Seir as far as El-paran near the wilderness

- The Amalekites in Kadesh at En-mishpat

- The Amorites in Hazezontamar

- The Canaanites of the cities of the Jordan plain[45]

Chedorlaomer's demise[edit]

After warring against the cities of the Plain at the Battle of Siddim, King Chedorlaomer went to Sodom and Gomorrah to collect booty. At Sodom, amongst the spoils of war, he took Lot and his entire household captive. When Lot's uncle, Abram received news of what happened, he assembled a battle unit of three hundred and eighteen men who pursued the Elamite forces north of Damascus to Hobah. Abram and one of his divisions defeated Chedorlaomer.[46] According to the King James Version, verse 17 is translated that Chedorlaomer was actually slaughtered.[47] Young's Literal Translation uses the term smiting.[48]

Identifying Chedorlaomer[edit]

Following the discovery of documents written in the Elamite language and Babylonian language, it was thought that Chedorlaomer is a transliteration of the Elamite compound Kudur-Lagamar, meaning servant of Lagamaru - a reference to Lagamaru, an Elamite deity whose existence was mentioned by Ashurbanipal. However, no mention of an individual named Kudur Lagamar has yet been found; inscriptions that were thought to contain this name are now known to have different names (the confusion arose due to similar lettering).[49][50] David Rohl identifies Chedorlaomer with an Elamite king named Kutir-Lagamar.

Simashki kinglist[edit]

| Throne Name | Original Name | Portrait | Title | Born-Died | Entered office | Left office | Family Relations | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | The unnamed king of Simashki | king of Simashki | ?–c. 2100 BC | ? | c. 2100 BC | ? | cont. Kutik-Inshushinak king of Awan | ||

| 21 | Gir-Namme I | king of Simashki | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | |||

| 22 | Tazitta I | king of Simashki | ?–? | c. 2040 BC[11] | c. 2037 BC[11] | ? | |||

| 23 | Eparti I | king of Simashki | ?–? | ? | c. 2033 BC[11] | ? | |||

| 24 | Gir-Namme II | king of Simashki | ?–? | c. 2033 BC | ? | ? | |||

| 25 | Tazitta II | king of Simashki | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | |||

| 26 | Lurak-Luhhan | king of Simashki | ?–2022 BC | c. 2028 BC | 2022 BC | ? | |||

| 27 | Hutran-Temti | king of Simashki | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | |||

| 28 | Indattu-Inshushinak I | king of Simashki | ?–2016 BC | ? | 2016 BC | son of Hutran-Temti | |||

| 29 | Kindattu | king of Simashki | ?–? | before 2006 BC | after 2005 BC | son of Tan-Ruhuratir | conqueror of Ur | ||

| 30 | Indattu-Inshushinak II | king of Simashki | ?–? | c. 1980 BC | ? | son of Pepi[12] | cont. Shu-Ilishu king of Isin & Bilalama king of Eshnunna | ||

| 32 | Tan-Ruhuratir I | king of Simashki | ?–? | c. 1965 BC | ? | son of Indattu-Inshushinnak II | cont. Iddin-Dagan king of Isin | ||

| 33 | Indattu-Inshushinak III | king of Simashki | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Tan-Ruhuratir I | more than 3 years | ||

| 35 | Indattu-Napir | king of Simashki | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | |||

| 36 | Indattu-Temti | king of Simashki | ?–? | ? | 1928? BC | ? | |||

Epartid dynasty[edit]

The succeeding dynasty, the Eparti (c. 1970–1770 BC), also called "of the sukkalmahs" because of the title borne by its members, was roughly contemporary with the Old Assyrian Empire, and Old Babylonian period in Mesopotamia, being younger by approximately sixty years than the Old Assyrian period, and almost around seventy five years older than the Old Babylonian period. This period is confusing and difficult to reconstruct. It was apparently founded by Eparti I. During this time, Susa was under Elamite control, but Mesopotamian states such as Larsa and Isin continually tried to retake the city. Around 1850 BC Kudur-mabug, apparently king of another Akkadian state to the north of Larsa, managed to install his son, Warad-Sin, on the throne of Larsa, and Warad-Sin's brother, Rim-Sin, succeeded him and conquered much of southern Mesopotamia for Larsa.

Notable Eparti dynasty rulers in Elam during this time include Sirukdukh (c. 1850 BC), who entered various military coalitions to contain the power of the south Mesopotamian states; Siwe-Palar-Khuppak, who for some time was the most powerful person in the area, respectfully addressed as "Father" by Mesopotamian kings such as Zimrilim of Mari, and even Hammurabi of Babylon, and Kudur-Nahhunte, who plundered the temples of southern Mesopotamia, the north being under the control of the Old Assyrian Empire. But Elamite influence in southern Mesopotamia did not last. Around 1760 BC, Hammurabi drove out the Elamites, overthrew Rim-Sin of Larsa, and established a short lived Babylonian Empire in Mesopotamia. Little is known about the latter part of this dynasty, since sources again become sparse with the Kassite rule of Babylon (from c. 1595 BC).

Susa[edit]

History[edit]

شوش (in Persian) | |

Tepe of the Royal city (left) and of the Acropolis (right), seen from the Hill mound of the Apadana in Susa. | |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 425: No value was provided for longitude. | |

| Location | Shush, Khuzestan Province, Iran |

|---|---|

| Region | Zagros Mountains |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | Approximately 4000 BCE |

| Abandoned | 1218 CE |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

| Official name | Susa |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv |

| Designated | 2015 (39th session) |

| Reference no. | 1455 |

| State party | Iran |

| Region | Asia-Pacific |

In historic literature, Susa appears in the very earliest Sumerian records: for example, it is described as one of the places obedient to Inanna, patron deity of Uruk, in Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta.

Susa is also mentioned in the Ketuvim of the Hebrew Bible by the name Shushan, mainly in Esther, but also once each in Nehemiah and Daniel. Both Daniel and Nehemiah lived in Susa during the Babylonian captivity of the 6th century BCE. Esther became queen there, and saved the Jews from genocide. A tomb presumed to be that of Daniel is located in the area, known as Shush-Daniel. The tomb is marked by an unusual white stone cone, which is neither regular nor symmetric. Many scholars believe it was at one point a Star of David. Susa is further mentioned in the Book of Jubilees (8:21 & 9:2) as one of the places within the inheritance of Shem and his eldest son Elam; and in 8:1, "Susan" is also named as the son (or daughter, in some translations) of Elam.

Greek mythology attributed the founding of Susa to king Memnon of Aethiopia, a character from Homer's Trojan War epic, the Iliad.

Proto-Elamite[edit]

In urban history, Susa is one of the oldest-known settlements of the region. Based on C14 dating, the foundation of a settlement there occurred as early as 4395 BCE (a calibrated radio-carbon date).[51] Archeologists have dated the first traces of an inhabited Neolithic village to c 7000 BCE. Evidence of a painted-pottery civilization has been dated to c 5000 BCE.[52] Its name in Elamite was written variously Ŝuŝan, Ŝuŝun, etc. The origin of the word Susa is from the local city deity Inshushinak. Like its Chalcolithic neighbor Uruk, Susa began as a discrete settlement in the Susa I period (c 4000 BCE). Two settlements called Acropolis (7 ha) and Apadana (6.3 ha) by archeologists, would later merge to form Susa proper (18 ha).[53] The Apadana was enclosed by 6m thick walls of rammed earth. The founding of Susa corresponded with the abandonment of nearby villages. Potts suggests that the city may have been founded to try to reestablish the previously destroyed settlement at Chogha Mish.[53] Susa was firmly within the Uruk cultural sphere during the Uruk period. An imitation of the entire state apparatus of Uruk, proto-writing, cylinder seals with Sumerian motifs, and monumental architecture, is found at Susa. Susa may have been a colony of Uruk. As such, the periodization of Susa corresponds to Uruk; Early, Middle and Late Susa II periods (3800–3100 BCE) correspond to Early, Middle, and Late Uruk periods.

By the middle Susa II period, the city had grown to 25 ha.[53] Susa III (3100–2900 BCE) corresponds with Uruk III period. Ambiguous reference to Elam (Cuneiform; 𒉏 NIM) appear also in this period in Sumerian records. Susa enters history during the Early Dynastic period of Sumer. A battle between Kish and Susa is recorded in 2700 BCE.

Susa Cemetery[edit]

Shortly after Susa was first settled 6000 years ago, its inhabitants erected a temple on a monumental platform that rose over the flat surrounding landscape. The exceptional nature of the site is still recognizable today in the artistry of the ceramic vessels that were placed as offerings in a thousand or more graves near the base of the temple platform. Nearly two thousand pots were recovered from the cemetery most of them now in the Louvre. The vessels found are eloquent testimony to the artistic and technical achievements of their makers, and they hold clues about the organization of the society that commissioned them.[54] Painted ceramic vessels from Susa in the earliest first style are a late, regional version of the Mesopotamian Ubaid ceramic tradition that spread across the Near East during the fifth millennium B.C.[54]

Susa I style was very much a product of the past and of influences from contemporary ceramic industries in the mountains of western Iran. The recurrence in close association of vessels of three types—a drinking goblet or beaker, a serving dish, and a small jar—implies the consumption of three types of food, apparently thought to be as necessary for life in the afterworld as it is in this one. Ceramics of these shapes, which were painted, constitute a large proportion of the vessels from the cemetery. Others are course cooking-type jars and bowls with simple bands painted on them and were probably the grave goods of the sites of humbler citizens as well as adolescents and, perhaps, children.[55] The pottery is carefully made by hand. Although a slow wheel may have been employed, the asymmetry of the vessels and the irregularity of the drawing of encircling lines and bands indicate that most of the work was done freehand.

Elamites[edit]

In politics, Susa was the capital of a state called Šušan, which occupied approximately the same territory of modern Khūzestān Province centered on the Karun River. Control of Šušan shifted between Elam, Sumer, and Akkad. Šušan is sometimes mistaken as synonymous with Elam, but it was a distinct cultural and political entity.[56] Šušan was incorporated by Sargon the Great into his Akkadian Empire in approximately 2330 BCE. It was the capital of an Akkadian province until ca. 2240 BCE, when its governor, Kutik-Inshushinak, rebelled and made it an independent state and a literary center. The city was subsequently conquered by the neo-Sumerian Ur-III dynasty and held until Ur finally collapsed at the hands of the Elamites under Kindattu in ca. 2004 BCE. At this time, Susa became an Elamite capital under the Epartid dynasty and, in 1400 BCE, of the Igihalkid dynasty that "Elamaized" Šušan.[56] In ca. 1175 BCE, the Elamites under Shutruk-Nahhunte plundered the original stele bearing the Code of Hammurabi, the world's first known written laws,[57] and took it to Susa. Archeologists found it in 1901. Nebuchadnezzar I of the Babylonian empire plundered Susa around fifty years later.

Anshan[edit]

History[edit]

Before 1973, when it was identified as Tall-i Malyan,[58] Anshan had been assumed by scholars to be somewhere in the central Zagros mountain range.[59]

The Elamite city appears to have been quite ancient; it makes an appearance in the early Sumerian epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta as being en route between Uruk and the legendary Aratta, supposedly around the time writing was developed. At various times, Anshan provided, in its own right, the source for a number of Elamite dynasties that sometimes competed for extent and influence with other prominent Elamite cities.

Manishtushu claimed to have subjugated Anshan, but as the Akkadian empire weakened under his successors, the native governor of Susa, Kutik-Inshushinak, a scion of the Awan dynasty, proclaimed his independence from Akkad and captured Anshan (some scholars have speculated that the name Awan is an alternate form of Anshan). Following this, Gudea of Lagash claimed to have subjugated Anshan, and the Neo-Sumerian rulers Shulgi and Shu-Sin of Ur are said to have maintained their own governors over the place. However their successor, Ibbi-Sin, seems to have spent his reign engaged in a losing struggle to maintain control over Anshan, ultimately resulting in the Elamite sack of Ur in 2004 BC, at which time the statue of Nanna, and Ibbi-Sin himself, were captured and removed to Anshan.[60] In the Old Babylonian period, king Gungunum of Larsa dated his 5th regnal year after the destruction of Anshan.

From the 15th century BC, Elamite rulers at Susa began using the title "King of Anshan and Susa" (in Akkadian texts, the toponyms are reversed, as "King of Susa and Anshan"),[61] and it seems probable that Anshan and Susa were in fact unified for much of the "Middle Elamite period". The last king to claim this title was Shutruk-Nahhunte II (ca. 717-699 BC).[62]

Epartid kinglist[edit]

| Throne Name | Original Name | Portrait | Title | Born-Died | Entered office | Left office | Family Relations | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | Eparti II | king of Anshan & Susa, Sukkalmah | ?–? | c. 1973 BC | ? | Married with a daughter of Iddin-Dagan king of Isin in 1973 BC.[63] | cont. Iddin-Dagan king of Isin | ||

| 34 | Shilhaha | king of Anshan & Susa, Sukkalmah | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Eparti II | |||

| 37 | Kuk-Nashur I | Sukkalmah | ?–? | ? | ? | son (ruhushak)[64] of Shilhaha | |||

| 38 | Atta-hushu | Sukkal and Ippir of Susa, Shepherd of the people of Susa, Shepherd of Inshushinak | ?–after 1894 BC | ?1928 BC | after 1894 BC | son of Kuk-Nashur I (?) | |||

| 39 | Tetep-Mada | Shepherd of the people of Susa | ?–? | after c. 1890 BC | ? | son of Kuk-Nashur I (?) | |||

| 40 | Palar-Ishshan | Sukkalmah | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | |||

| 41 | Kuk-Sanit | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Palar-Ishshan (?) | ||||

| 42 | Kuk-Kirwash | Sukkalmah, Sukkal of Elam and Simashki and Susa | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Lan-Kuku & nephew of Palar-Ishshan | |||

| 43 | Tem-Sanit | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Kuk-Kirwash | ||||

| 44 | Kuk-Nahhunte | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Kuk-Kirwash | ||||

| 45 | Kuk-Nashur II | Sukkalmah, Sukkal of Elam, Sukkal of Elam and Simashki and Susa | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Kuk-Nahhunte (?) | |||

| 46 | Shirukduh | Sukkalmah | ?–? | c. 1790 BC | ? | ? | cont. Shamshi-Adad I king of Assyria | ||

| 47 | Shimut-Wartash I | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Shirukduh | ||||

| 48 | Siwe-Palar-Hupak | Sukkalmah, Sukkal of Susa, Prince of Elam | ?–? | before 1765 BC | after 1765 BC | son of Shirukduh | |||

| 49 | Kuduzulush I | Sukkalmah, Sukkal of Susa | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Shirukduh | |||

| 50 | Kutir-Nahhunte I | Sukkalmah | ?–? | c. 1710 BC | ? | son of Kuduzulush I | |||

| 51 | Atta-Merra-Halki | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Kuduzulush I (?) | ||||

| 52 | Tata II | Sukkal | ?–? | ? | ? | brother of Atta-Merra-Halki | |||

| 53 | Lila-Irtash | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Kuduzulush I | ||||

| 54 | Temti-Agun | Sukkalmah, Sukkal of Susa | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Kutir-Nahhunte I | |||

| 55 | Kutir-Shilhaha | Sukkalmah, Sukkal | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Temti-Agun | |||

| 56 | Kuk-Nashur III | Sukkal of Elam, Sukkal of Susa | ?–? | before 1646 BC | after 1646 BC | son of Kutir-Shilhaha | |||

| 57 | Temti-Raptash | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Kutir-Shilhaha | ||||

| 58 | Shimut-Wartash II | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Kuk-Nashur III | ||||

| 59 | Shirtuh | King of Susa | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Kuk-Nashur III | |||

| 60 | Kuduzulush II | Sukkalmah, King of Susa | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Shimut-Wartash II | |||

| 61 | Tan-Uli | Sukkalmah, Sukkal | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | |||

| 62 | Temti-Halki | Sukkalmah, Sukkal of Elam and Simashki and Susa | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Tan-Uli | |||

| 63 | Kuk-Nashur IV[11] | Sukkalmah | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Tan-Uli | |||

| 64 | Kutik-Matlat[10] | ?–? | c. 1500 BC | ? | son of Tan-Uli | ||||

Population[edit]

Anshan, one of Elam's largest cities, has been estimated to have had a population at its height of 10,000;[65] The world population at this time has been estimated at about 27m.[66]

Elamite is an extinct language spoken by the ancient Elamites. Elamite was the primary language in present-day Iran from 2800–550 BC. The last written records in Elamite appear about the time of the conquest of the Persian Empire by Alexander the Great. Elamite has no demonstrable relatives, and is usually considered a language isolate. Partly due to the lack of established relatives, interpretation of the language is difficult.

The Nostratic language family is a proposed macrofamily grouping together a number of language families including Indo-European, Uralic, Altaic, and more controversially Afroasiatic. Following Pedersen, Illich-Svitych, and Dolgopolsky, most advocates of the theory have included Afroasiatic in Nostratic, though criticisms by Joseph Greenberg and others from the late 1980s onward suggested a reassessment of this position.

Ilya Yabonovich and other linguists, in examining the differences between the various members of the Afroasiatic family have realised that all of the old etymologies for this group were inherently semitocentric. The differences between Chadic, Omotic, Cushitic and Semitic, were wider than those seen between any members of the Indo-European family and as wide as some of the differences seen within and between separate language families, for example, Indo-European and Altaic. Certainly the exclusion of Afroasiatic from the controversial Nostratic family has simplified matters of phonemics, not having to include the complex patterns seen in Afroasiatic languages.

Allan Bomhard (1994) retains Afroasiatic within Nostratic, despite his admission that Proto–Afroasiatic is very different from the other members of the proposed linguistic Nostratic superfamily.[67] As a result he suggests it was probably the first language to have split from the Nostratic linguistic superfamily. Recently, however, a consensus has been emerging among proponents of the Nostratic hypothesis. Greenberg in fact basically agreed with the Nostratic concept, though he stressed a deep internal division between its northern 'tier' (his Eurasiatic) and a southern 'tier' (principally Afroasiatic and Dravidian). The American Nostraticist Bomhard considers Eurasiatic a branch of Nostratic alongside other branches: Afroasiatic, Elamo-Dravidian, and Kartvelian. Similarly, Georgiy Starostin (2002) arrives at a tripartite overall grouping: he considers Afroasiatic, Nostratic and Elamite to be roughly equidistant and more closely related to each other than to anything else.[68] Sergei Starostin's school has now re-included Afroasiatic in a broadly defined Nostratic, while reserving the term Eurasiatic to designate the narrower subgrouping which comprises the rest of the macrofamily. Recent proposals thus differ mainly on the precise placement of Dravidian and Kartvelian.

Culture[edit]

Religion[edit]

Deities[edit]

The Elamites practised polytheism. Knowledge about their religion is scant, but, according to Cambridge Ancient History, at one time they had a pantheon headed by the goddess Kiririsha/Pinikir.[69]

The Elamites worshiped:

- Kiririsha (or Kirisha) at one stage became the most important goddess of Elam, ranked second only to her husband the god, Humban. Along with Humban and another god, Inshushinak, she formed part of the supreme triad of the Elamite pantheon. Kiririsha, which in Elamite means "the Great Goddess", was first known as the 'Lady of Liyan' - an Elamite port on Persian Gulf (near modern-day Bushire, Iran), where she and Humban had a temple that was erected by Humban-Numena. There was later (ca. 1250 BC) a temple built to her at Chogha Zanbil. She was often called 'the Great', or 'the divine mother'. She seems to have been primarily worshipped in the south of Elam, as another goddess, Pinikir, held her position in the north. Eventually, by about 1800 BC, the two had merged and the cult of Kiririsha also came to be practised in Susiana.

- Pinikir was an Elamite mother-goddess who some scholars have identified with the goddess Kirrisi or Kiririsha.[70][71]

- Napir was the Elamite god of the moon. At least three Elamite kings bore this name in the god's honor, which is consistent with the fact that nearly all rulers of Elam bore theophoric names. One of them was Untash-Napirisha, who lived in the 13th century BC. Some sources suggest that the meaning of his name is "the shining one", but it is more likely that it is derived from the Elamite word 'nap or 'napir' meaning "God".

- Khumban is the Elamite god of the sky. His sumerian equivalent is Anu. Several Elamite kings, mostly from the Neo-Elamite period, were named in honour of Khumban.

- Inshushinak was one of the major gods of the Elamites and the protector deity of Susa. The ziggurat at Choqa Zanbil is dedicated to him.

- Jabru was the Elamite god of the underworld. He was the father of all Elamite gods. Jabru's Akkadian counterpart was Anu.

- Lahurati is a god of the Elamite pantheon. Lahurati appears to have been the counterpart of the Akkadian god Ninurta.

- Narundi is a goddess whose statue was dedicated by Kutik-Inshushinak.

Language[edit]

Elamite is an extinct language spoken by the ancient Elamites. Elamite was the primary language in present-day Iran from 2800–550 BC. The last written records in Elamite appear about the time of the conquest of the Persian Empire by Alexander the Great. Elamite has no demonstrable relatives, and is usually considered a language isolate. Partly due to the lack of established relatives, interpretation of the language is difficult.[72]

Writing system[edit]

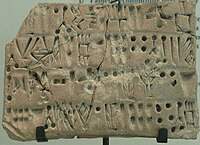

| Elamite Cuneiform | |

|---|---|

| Script type | |

Time period | 2200 BCE to 400 BCE |

| Languages | Elamite language |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Sumerian Cuneiform

|

Sister systems | Old Persian Cuneiform |

Elamite cuneiform was a logo-syllabic script used to write the Elamite language.

History and decipherment[edit]

The Elamite language (c. 3000 BCE to 400 BCE) is the now-extinct language spoken by Elamites, who inhabited the regions of Khuzistān and Fārs in Southern Iran.[73] It has long been an enigma for scholars due to the scarcity of resources for its research and the irregularities found in the language.[73] It seems to have no relation to its neighboring Semitic and Indo-European languages.[74] Scholars fiercely argue over several hypotheses about its origin, but have no definite theory.

Elamite cuneiform comes in two variants, the first, derived from Akkadian, was used during the 3rd to 2nd millennia BCE, and a simplified form used during the 1st millennium BCE.[73] The main difference between the two variants is the reduction of glyphs used in the simplified version.[75] At any one time, there would only be around 130 cuneiform signs in use. Throughout the script’s history, only 206 different signs were used in total.

The earliest known Elamite cuneiform text is a treaty between Akkaddians and the Elamites that dates back to 2200 BCE.[73] However, some believe it might have been in use since 2500 BCE [75] The tablets are poorly preserved so only limited parts can be read but it is understood that the text is a treaty between the Akkad king Nāramsîn and Elamite ruler Hita. Frequent references like "Nāramsîn's friend is my friend, Nāramsîn's enemy is my enemy" indicate so.[73]

The most famous and the ones that ultimately lead to its decipherment are the Elamite scriptures found in the trilingual inscriptions of monuments commissioned by the Achaemenid Persian kings.[76] The inscriptions, similar to that of the Rosetta Stone's, were written in three different writing systems. The first was Old Persian, which was deciphered in 1802 by Georg Friedrich Grotefend. The second, Babylonian cuneiform, was deciphered shortly after the Old Persian text. Because Elamite is unlike its neighboring Semitic languages, the script's decipherment was delayed until the 1840s. Even today, lack of sources and comparative materials hinder further research of Elamite.[73]

Inventory[edit]

Elamite radically reduced the number of cuneiform glyphs. From the entire history of the script, only 206 glyphs are used; at any one time, the number was fairly constant at about 130. In the earliest tablets the script is almost entirely syllabic, with almost all common Old Akkadian syllabic glyphs with CV and VC values being adopted. Over time the number of syllabic glyphs is reduced while the number of logograms increases. About 40 CVC glyphs are also occasionally used, but they appear to have been used for the consonants and ignored the vocalic value. Several determinatives are also used.[75]

Glyphs in parentheses in the table are not common.[need to find ka4 and tu4]

The script distinguished the four vowels of Akkadian and 15 consonants, /p/, /b/,/k/,/g/,/t/,/d/,/š/,/s/,/z/,/y/,/l/,/m/,/n/,/r/, and /h/. The Akkadian voiced pairs /p, b/, /k, g/, and /t, d/ may not have been distinct in Elamite. The series transcribed z may have been an affricate such as /č/ or /c/ (ts). /hV/ was not always distinguished from simple vowels, suggesting that /h/ may have been dropping out of the language. The VC glyphs are often used for a syllable coda without any regard to the value of V, suggesting that they were in fact alphabetic C signs.[75]

Much of the conflation of Ce and Ci, and also eC and iC, is inherited from Akkadian (pe-pi-bi, ke-ki, ge-gi, se-si, ze-zi, le-li, re-ri, and ḫe-ḫi—that is, only ne-ni are distinguished in Akkadian but not Elamite; of the VC syllables, only eš-iš-uš). In addition, 𒄴 is aḫ, eḫ, iḫ, uḫ in Akkadian, and so effectively is a coda consonant even there.

Syntax[edit]

Elamite cuneiform is similar to that of Akkadian cuneiform except for a few unusual features. For example, the primary function of CVC glyphs was to indicate the two consonants rather than the syllable.[75] Thus certain words used the glyphs for “tir” and “tar” interchangeably and the vowel was ignored. Occasionally, the vowel is acknowledged such that “tir” will be used in the context “ti-rV”. Thus “ti-ra” might be written with the glyphs for “tir” and “a” or “ti” and “ra”.

Elamite cuneiform allows for a lot of freedom when constructing syllables. For example, CVC syllables are sometimes represented by using a CV and VC glyph. The vowel in the second glyph is irrelevant so “sa-ad” and “sa-ud” are equivalent. Additionally, “VCV” syllables are represented by combining “V” and “CV” glyphs or “VC” and “CV” glyphs that have a common consonant. Thus “ap-pa” and “a-pa” are equivalent.

Linguistic typology[edit]

Elamite was an agglutinative language,[77] and Elamite grammar was characterized by a well-developed and pervasive nominal class system, where animate nouns had separate markers for 1st, 2nd, and 3rd person – the latter being a rather unusual feature. It can be said to display a kind of Suffixaufnahme in that the nominal class markers of the head were also attached to any modifiers, including adjectives, noun adjuncts, possessor nouns, and even entire clauses.

History[edit]

The history of Elamite is periodized as follows:

- Old Elamite (c. 2600–1500 BC)

- Middle Elamite (c. 1500–1000 BC)

- Neo-Elamite (1000–550 BC)

- Achaemenid Elamite (550–330 BC)

Middle Elamite is considered the “classical” period of Elamite, whereas the best attested variety is Achaemenid Elamite,[78] which was widely used by the Achaemenid Persian state for official inscriptions as well as administrative records and displays significant Old Persian influence. Documents from the Old Elamite and early Neo-Elamite stages are rather scarce. Neo-Elamite can be regarded as a transition between Middle and Achaemenid Elamite with respect to language structure.

Sound system[edit]

| Elamite | |

|---|---|

Tablet of Elamite script | |

| Native to | Elamite Empire |

| Region | Middle East |

| Era | ca. 2800–300 BC |

Early forms | language of Proto-Elamite?

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | elx |

| ISO 639-3 | elx |

elx | |

| Glottolog | elam1244 |

Because of the limitations of the scripts, Elamite phonology is not well understood. In terms of consonants, it had at least the stops /p/, /t/ and /k/, the sibilants /s/, /š/ and /z/ (with uncertain pronunciation), the nasals /m/ and /n/, the liquids /l/ and /r/, and a fricative /h/, which was lost in late Neo-Elamite. Some peculiarities of spelling have been interpreted as suggesting that there was a contrast between two series of stops (/p/, /t/, /k/ vs /b/, /d/, /g/), but in general such a distinction is not consistently indicated by written Elamite. As for the vowels, Elamite had at least /a/, /i/, and /u/, and may also have had an /e/, which is, however, not generally expressed unambiguously.

Roots are generally of the forms CV, (C)VC, (C)VCV, and more rarely CVCCV (where the first C is usually a nasal).

Grammar[edit]

Elamite is agglutinative (but with fewer morphemes per word than, for example, Sumerian or Hurrian and Urartian), and predominantly suffixing.

Nominal morphology[edit]

The Elamite nominal system is thoroughly pervaded by a noun class distinction which combines a gender distinction between animate and inanimate with a personal class distinction corresponding to the three persons of verbal inflection (first, second, third, plural).

The suffixes are as follows:

Animate:

- 1st person singular: -k

- 2nd person singular: -t

- 3rd person singular: -r or Ø

- 3rd person plural: -p

Inanimate:

- -Ø, -me, -n, -t[clarification needed]

The animate third-person suffix -r can serve as a nominalizing suffix and indicate nomen agentis or just members of a class. The inanimate 3rd singular -me forms abstracts. Some examples are sunki-k “a king (first person)” i.e. “I, a king”, sunki-r “a king (third person)”, nap-Ø or nap-ir “a god (third person)”, sunki-p “kings”, nap-ip “gods”, sunki-me “kingdom, kingship”, hal-Ø “town, land”, siya-n “temple”, hala-t “mud brick”.

Modifiers follow their (nominal) heads. In noun phrases and pronoun phrases, the suffixes referring to the head are appended to the modifier, regardless of whether the modifier is another noun (such as a possessor) or an adjective. Sometimes the suffix is preserved on the head as well.

Examples:

- u šak X-k(i) = “I, the son of X”

- X šak Y-r(i) = “X, the son of Y”

- u sunki-k Hatamti-k = “I, the king of Elam”

- sunki Hatamti-p (or, sometimes, sunki-p Hatamti-p) = “the kings of Elam”

- temti riša-r = “great lord” (lit. “lord great”)

- riša-r nap-ip-ir = “greatest of the gods” (lit. “great of the gods)

- nap-ir u-ri = my god (lit. “god of me”)

- hiya-n nap-ir u-ri-me = the throne hall of my god

- takki-me puhu nika-me-me = “the life of our children”

- sunki-p uri-p u-p(e) = ”kings, my predecessors” (lit. “kings, predecessors of me”)

This system, in which the noun class suffixes function as derivational morphemes as well as agreement markers and indirectly as subordinating morphemes, is best seen in Middle Elamite. It is, to a great extent, broken down in Achaemenid Elamite, where possession and, sometimes, attributive relationships are uniformly expressed with the “genitive case” suffix -na appended to the modifier: e.g. šak X-na “son of X”. The suffix -na, which probably originated from the inanimate agreement suffix -n followed by the nominalizing particle -a (see below), appeared already in Neo-Elamite.

The personal pronouns distinguish nominative and accusative case forms. They are as follows:

| Case | 1st sg. | 2nd sg. | 3rd sg. | 1st pl. | 2nd pl. | 3rd pl. | Inanimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | u | ni/nu | i/hi | nika/nuku | num/numi | ap/appi | i/in |

| Accusative | un | nun | ir/in | nukun | numun | appin | i/in |

In general, no special possessive pronouns are needed in view of the construction with the noun class suffixes. Nevertheless, a set of separate third-person animate possessives -e (sing.) / appi-e (plur.) is occasionally used already in Middle Elamite: puhu-e “her children”, hiš-api-e “their name”. The relative pronouns are akka “who” and appa “what, which”.

Verbal morphology[edit]

The verb base can be simple (e.g. ta- “put”) or “reduplicated” (e.g. beti > bepti “rebel”). The pure verb base can function as a verbal noun or “infinitive”.

The verb distinguishes three forms functioning as finite verbs, known as “conjugations”. Conjugation I is the only one that has special endings characteristic of finite verbs as such, as shown below. Its use is mostly associated with active voice, transitivity (or verbs of motion), neutral aspect and past tense meaning. Conjugations II and III can be regarded as periphrastic constructions with participles; they are formed by the addition of the nominal personal class suffixes to a passive perfective participle in -k and to an active imperfective participle in -n, respectively. Accordingly, conjugation II expresses a perfective aspect, hence usually past tense, and an intransitive or passive voice, whereas conjugation III expresses an imperfective non-past action.

The Middle Elamite conjugation I is formed with the following suffixes:

- 1st singular: -h

- 2nd singular: -t

- 3rd singular: -š

- 1st plural: -hu

- 2nd plural: -h-t

- 3rd plural: -h-š

Examples: kulla-h ”I prayed”, hap-t ”you heard”, hutta-š “he did”, kulla-hu “we prayed”, hutta-h-t “you (plur.) did”, hutta-h-š “they did”. In Achaemenid Elamite, the loss of the /h/ phoneme reduces the transparency of the Conjugation I endings and leads to the merger of the singular and plural except in the first person; in addition, the first person plural changes from -hu to -ut.

The participles can be exemplified as follows: perfective participle hutta-k “done”, kulla-k “something prayed”, i.e. “a prayer”; imperfective participle hutta-n “doing” or “who will do”, also serving as a non-past infinitive. The corresponding conjugation is, for the perfective, first person singular hutta-k-k, second person singular hutta-k-t, third person singular hutta-k-r, third person plural hutta-k-p; and for the imperfective, 1st person singular hutta-n-k, 2nd person singular hutta-n-t, 3rd person singular hutta-n-r, 3rd person plural hutta-n-p. In Achaemenid Elamite, the Conjugation 2 endings are somewhat changed: 1st person singular hutta-k-ut, 2nd person singular hutta-k-t, 3rd person singular hutta-k (hardly ever attested in predicative use), 3rd person plural hutta-p.

There is also a periphrastic construction with an auxiliary verb ma- following either Conjugation II and III stems (i.e. the perfective and imperfective participles), or nomina agentis in -r, or a verb base directly. In Achaemenid Elamite, only the third option exists. There is no consensus on the exact meaning of the periphrastic forms with ma-, although durative, intensive or volitional interpretations have been suggested.[79]

Optative mood is expressed by the addition of the suffix -ni to Conjugations I and II. The imperative is identical to the second person of Conjugation I in Middle Elamite. In Achaemenid Elamite, it is the third person that coincides with the imperative. The prohibitative is formed by the particle ani/ani preceding Conjugation III.

Verbal forms can be converted into the heads of subordinate clauses through the addition of the suffix -a, much as in Sumerian: siyan in-me kuši-hš(i)-me-a “the temple which they did not build”. -ti/-ta can be suffixed to verbs, chiefly of conjugation I, expressing possibly a meaning of anteriority (perfect and pluperfect tense).

The negative particle is in-; it takes nominal class suffixes that agree with the subject of attention (which may or may not coincide with the grammatical subject), e.g. first person singular in-ki, third person singular animate in-ri, third person singular inanimate in-ni/in-me. In Achaemenid Elamite, the inanimate form in-ni has been generalized to all persons, so that concord has been lost.

Syntax[edit]

Nominal heads are normally followed by their modifiers, although there are occasional inversions of this word order. The word order is subject–object–verb (SOV), with indirect objects preceding direct objects, although the word order becomes more flexible in Achaemenid Elamite. There are often resumptive pronouns before the verb – often long sequences, especially in Middle Elamite (ap u in duni-h "to-them I it gave").

The language uses postpositions such as -ma "in" and -na "of", but spatial and temporal relationships are generally expressed in Middle Elamite by means of "directional words" originating as nouns or verbs. These "directional words" either precede or follow the governed nouns, and tend to exhibit noun class agreement with whatever noun is described by the prepositional phrase: e.g. i-r pat-r u-r ta-t-ni "may you place him under me", lit. "him inferior of-me place-you-may". In Achaemenid Elamite, postpositions become more common and partly, but not entirely, displace this type of construction.

A common conjunction is ak "and, or". Achaemenid Elamite also uses a number of subordinating conjunctions such as anka "if, when", sap "as, when", etc. Subordinate clauses usually precede the verb of the main clause. In Middle Elamite, the most common way to construct a relative clause is to attach a nominal class suffix to the clause-final verb, optionally followed by the relativizing suffix -a: thus, lika-me i-r hani-š-r(i) "whose reign he loves", or optionally lika-me i-r hani-š-r-a. The alternative construction by means of the relative pronouns akka "who" and appa "which" is uncommon in Middle Elamite, but gradually becomes dominant at the expense of the nominal class suffix construction in Achaemenid Elamite.

Language samples[edit]

Middle Elamite (Šutruk-Nahhunte I, 1200–1160 BC; EKI 18, IRS 33):

Transliteration:

(1) ú DIŠšu-ut-ru-uk-d.nah-hu-un-te ša-ak DIŠhal-lu-du-uš-din-šu-ši-

(2) -na-ak-gi-ik su-un-ki-ik an-za-an šu-šu-un-ka4 e-ri-en-

(3) -tu4-um ti-pu-uh a-ak hi-ya-an din-šu-ši-na-ak na-pír

(4) ú-ri-me a-ha-an ha-li-ih-ma hu-ut-tak ha-li-ku-me

(5) din-šu-ši-na-ak na-pír ú-ri in li-na te-la-ak-ni

Transcription:

U Šutruk-Nahhunte, šak Halluduš-Inšušinak-ik, sunki-k Anzan Šušun-ka. Erientum tipu-h ak hiya-n Inšušinak nap-ir u-ri-me ahan hali-h-ma. hutta-k hali-k u-me Inšušinak nap-ir u-ri in lina tela-k-ni.

Translation:

I, Šutruk-Nahhunte, son of Halluduš-Inšušinak, king of Anshan and Susa. I moulded bricks and made the throne hall of my god Inšušinak with them. May my work come as an offering to my god Inšušinak.

Achaemenid Elamite (Xerxes I, 486–465 BC; XPa):

Transliteration:

(01) [sect 01] dna-ap ir-šá-ir-ra du-ra-mas-da ak-ka4 AŠmu-ru-un

(02) hi pè-iš-tá ak-ka4 dki-ik hu-ip-pè pè-iš-tá ak-ka4 DIŠ

(03) LÚ.MEŠ-ir-ra ir pè-iš-tá ak-ka4 ši-ia-ti-iš pè-iš-tá DIŠ

(04) LÚ.MEŠ-ra-na ak-ka4 DIŠik-še-ir-iš-šá DIŠEŠŠANA ir hu-ut-taš-

(05) tá ki-ir ir-še-ki-ip-in-na DIŠEŠŠANA ki-ir ir-še-ki-ip-

(06) in-na pír-ra-ma-ut-tá-ra-na-um

Transcription:

Nap irša-rra Uramasda, akka muru-n hi pe-š-ta, akka kik hupe pe-š-ta, akka ruh(?)-irra ir pe-š-ta, akka šiatiš pe-š-ta ruh(?)-ra-na, akka Ikšerša sunki(?) ir hutta-š-ta kir iršeki-pi-na sunki(?), kir iršeki-pi-na piramataram.

Translation:

A great god is Ahura Mazda, who created this earth, who created that sky, who created man, who created happiness of man, who made Xerxes king, one king of many, one lord of many.

Relations to other language families[edit]

Elamite is regarded by the vast majority of linguists as a language isolate, as it has no demonstrable relationship to the neighbouring Semitic languages, Indo-European languages, or to Sumerian, despite having adopted the Sumerian-Akkadian cuneiform script. An Elamo-Dravidian family connecting Elamite with the Dravidian languages of India was suggested by Igor M. Diakonoff, and has been later defended by David McAlpin in several articles. Václav Blažek proposed a relation with the Afroasiatic languages of the Near East,[80] and George Starostin published a lexicostatistic analysis finding Elamite to be approximately equidistant from Nostratic and Semitic,[81] but these ideas have not been picked up by mainstream historical linguists.[why?][citation needed]

Women in Elam[edit]

At times, Elam was matriarchal society, thus women leading over men and all society. In general, women's rights in Mesopotamia were not equal to those of men.[citation needed] But in early periods women were free to go out to the marketplaces, buy and sell, attend to legal matters for their absent men, own their own property, borrow and lend, and engage in business for themselves. High status women, such as priestesses and members of royal families, might learn to read and write and be given considerable administrative authority. Numerous powerful goddesses were worshiped; in some city states they were the primary deities.[citation needed] The position of women varied between city-states and changed over time. There was an enormous gap between the rights of high and low status women (almost half the population in the late Babylonian period were slaves), and female power and freedom sharply diminished during the Assyrian era. The first evidence of laws requiring the public veiling of elite women come from this period.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Kent, Roland (1953). Old Persian: Grammar, Texts & Lexicon. American Oriental Series. Vol. 33). American Oriental Society. p. 53. ISBN 0-940490-33-1.

- ^ Jeremy Black, Andrew George & Nicholas Postgate (eds.), ed. (1999). A Concise Dictionary of Akkadian. Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 68. ISBN 3-447-04225-7.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ Legrain, 1922, pp. 10, 12, 22.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia Iranica, "AWAN"

- ^ Cameron, 1936; Hinz, 1972; The Cambridge Ancient History; Vallat, 1998.

- ^ The Archaeology of Elam, by Daniel T. Potts, Cambridge University Press, p. 124 [1]

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica: Elam - Simashki dynasty, F. Vallat

- ^ Wilcke; See Encyclopedia Iranica articles AWAN, ELAM

- ^ see Hansman; Encyclopedia Iranica, "Anshan".

- ^ a b Cameron, 1936.

- ^ a b c d e Potts, 1999.

- ^ a b Hinz, 1972.

- ^ Victor Harold Matthews; Don C. Benjamin (2006). Old Testament parallels: laws and stories from the ancient Near East. Paulist Press. pp. 248–. ISBN 978-0-8091-4435-8. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ a b George Aaron Barton (1918). Miscellaneous Babylonian inscriptions, p. 45. Yale University Press. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ Edward Chiera; Samuel Noah Kramer; University of Pennsylvania. University Museum. Babylonian Section (1934). Sumerian texts of varied contents, p. 1-. The University of Chicago Press. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Musée du Louvre. Département des antiquités orientales et de la céramique antique; Musée du Louvre. Département des antiquités orientales. Textes cunéiformes, 16, 40. Librairie orientaliste, Paul Geuthner.

- ^ Ashmolean Museum (1976). Oxford Editions of Cuneiform Texts, 12, 13, 14 and 15. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Universität. Jena. Frau Professor Hilprecht Collection of Babylonian Antiquities (19??). Texte und Materialien der Frau-Professor-Hilprecht-Collection of Babylonian antiquities: Neue Folge, 4 18, 4 19, 4 21, 4 20, 4 22, 4 23, 4 24 and 4 25. Hinrichs. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ University of Chicago. Dept. of Oriental Languages and Literatures (1970). Journal of Near Eastern studies, pl. 1 and 2. Univ. of Chicago Press.

- ^ Samuel Noah Kramer (1944). Sumerian literary texts from Nippur: in the Museum of the Ancient Orient at Istanbul, 32, 45, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98 and 99. American Schools of Oriental Research. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ Muazzez Cig; Hatice Kizilyay (1969). Sumerian literary tablets and fragments in the archeological museum of Istanbul-I, 81, 95, 100, 107, 115, 118, 139, 142 and 147. Tarih Kurumu Basimevi. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ Edward Chiera; Constantinople. Musée impérial ottoman (1924). Sumerian religious texts, 32 & 45. University. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ British museum and Pennsylvania University. University museum. Joint expedition to Mesopotamia; Pennsylvania University. University museum (1928). Ur excavations texts... 6 137, 6 135, 6 136, 6 137, 6 138, 6 139, 6 *290. British museum. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ Königliche Museen zu Berlin. Vorderasiatische Abteilung; Heinrich Zimmern; Otto Schroeder; H. H. Figulla; Wilhelm Förtsch; Friedrich Delitzsch. Vorderasiatische Schriftdenkmäler 10, 141. Louis D. Levine. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d e The Lament for Ur., Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998-.

- ^ ETCSLtransliteration : c.4.80.2

- ^ a b Dale Launderville (2003). Piety and politics: the dynamics of royal authority in Homeric Greece, biblical Israel, and old Babylonian Mesopotamia. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 248–. ISBN 978-0-8028-3994-7. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ Kenneth R. Wade (February 2004). Journey to Moriah: The Untold Story of How Abraham Became the Friend of God. Pacific Press Publishing. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-0-8163-2024-0. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ a b J. Harold Ellens; Deborah L. Ellens; Rolf P. Knierim; Isaac Kalimi (2004). God's Word for Our World: Biblical studies in honor of Simon John De Vries. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 287–. ISBN 978-0-8264-6974-8. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ Karen Weisman (6 June 2010). The Oxford handbook of the elegy. Oxford University Press. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-0-19-922813-3. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ Institut orientaliste de Louvain (1977). Orientalia Lovaniensia periodica. Instituut voor Oriëntalistiek. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ a b Piotr Michalowski (1989). The lamentation over the destruction of Sumer and Ur. Eisenbrauns. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-0-931464-43-0. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ Sabrina P. Ramet (1996). Gender reversals and gender cultures: anthropological and historical perspectives. Psychology Press. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-0-415-11482-0. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ Philip S. Alexander (1 December 2007). The Targum of Lamentations. Liturgical Press. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-0-8146-5864-2. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ a b Peter G. Tsouras (24 October 2005). The Book of Military Quotations. Zenith Imprint. pp. 12–. ISBN 978-0-7603-2340-3. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ Michelle Breyer (December 1997). Ancient Middle East. Teacher Created Resources. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-1-55734-573-8. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ כְּדָרְלָעֹמֶר [Chedorlaomer], retrieved 21 December 2012

- ^ Genesis 14:1

- ^ Knanishu, Joseph (1899), About Persia and its People, Lutheran Augustana book concern, printers, p. 228, retrieved 21 December 2012

- ^ Kitchen, Kenneth (1966), Ancient Orient and Old Testament, Tyndale Press, p. 44, retrieved 21 December 2012

- ^ Archer, Gleason Jr (19 April 2011), "Genesis", New International Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties, Zondervan, p. 175, ISBN 978-0-310-87337-2, retrieved 21 December 2012

- ^ a b "Chedorlaomer", Jewish Encyclopedia, retrieved 21 December 2012

- ^ a b Nelson, Russell (November 2000), "Chedorlaomer", in Freedman, David; Meyers, Allen; Beck, Astrid (eds.), Eerdman's Dictionary of the Bible, Grand Rapids: Wm B Eerdmans Publishing Company, p. 232, ISBN 9780802824004, retrieved 21 December 2012

- ^ Genesis 14:1–4

- ^ Gen.14:8–10

- ^ Genesis 14:11–17

- ^ Genesis 14:17

- ^ Genesis 14:17

- ^ 'Chedorlaomer' at JewishEncyclopedia.com

- ^ Kudur-Lagamar from History of Egypt by G. Maspero

- ^ The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State - by D. T. Potts, Cambridge University Press, 29/07/1999 - page 46 - ISBN 0521563585 hardback

- ^ Langer, William L., ed. (1972). An Encyclopedia of World History (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 17. ISBN 0-395-13592-3.

- ^ a b c Potts, 1999

- ^ a b Aruz, Joan (1992). The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre. New York: Abrams. p. 26.

- ^ Aruz, Joan (1992). The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre. New York: Abrams. p. 29.

- ^ a b Vallat, 2010

- ^ http://www.justlawlinks.com/REGS/codeham.htm

- ^ Reiner, Erica (1973) "The Location of Anšan", Revue d'Assyriologie 67, pp. 57-62 (cited in Majidzadeh (1976), Hansman (1985))

- ^ e.g. Gordon (1967) p. 72 note 9. Kermanshah; Mallowan (1969) p. 256. Bakhtiari territory (cited in Mallowan (1985) p. 401, note 1)

- ^ Cambridge History of Iran p. 26-27

- ^ Birth of the Persian Empire

- ^ Cambridge History of Iran

- ^ Vallat, "Elam ...", 1998.

- ^ "Ruhushak" means son of sister but probably it refers to a dynastical marriage between siblings. See Vallat, "Elam ...", 1998.

- ^ [2]

- ^ Colin McEvedy and Richard Jones, 1978, Atlas of World Population History, Facts on File, New York, ISBN 0-7139-1031-3.

- ^ Bomhard, Alan and John Kerns (1994) "The Nostratic Macrofamily: A Study in Distant Linguistic Relationship" (Walter de Gruyter)

- ^ George Starostin, On the genetic affiliation of the Elamite language

- ^ http://books.google.com.br/books?id=n1TmVvMwmo4C&printsec=frontcover&hl=pt-BR The Cambridge Ancient History, p. 400

- ^ Edwards, I.E.S. (3 edition (31 Oct 1971)). The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 1, Part 2: Early History of the Middle East. Cambridge University Press. p. 665. ISBN 978-0-521-07791-0.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lurker, Manfred (27 May 2004). The Routledge dictionary of gods and goddesses, devils and demons (2nd ed.). Psychology Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-415-34018-2.

- ^ Elamite (2005). Keith Brown (ed.). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-044299-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Khačikjan (1998)

- ^ Starostin, George (2002)

- ^ a b c d e Peter Daniels and William Bright (1996)

- ^ Reiner, Erica (2005)

- ^ Stolper, Matthew W. 2008. Elamite. In The Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Aksum. P.60: "Elamite is an agglutinative language."

- ^ Brown, Keith and Sarah Ogilvie. Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world. P.316

- ^ Stolper, Matthew W. 2008. Elamite. In The Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Aksum. P. 67

- ^ Blench 2006, p. 96

- ^ Starostin 2002

Further reading[edit]

- Quintana Cifuentes, E., Historia de Elam el vecino mesopotámico, Murcia, 1997. Estudios Orientales. IPOA-Murcia.

- Quintana Cifuentes, E., Textos y Fuentes para el estudio del Elam, Murcia, 2000.Estudios Orientales. IPOA-Murcia.

- Quintana Cifuentes, E., La Lengua Elamita (Irán pre-persa), Madrid, 2010. Gram Ediciones. ISBN 978-84-88519-17-7

- Khačikjan, Margaret: The Elamite Language, Documenta Asiana IV, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Istituto per gli Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici, 1998 ISBN 88-87345-01-5

- Persians: Masters of Empire, Time-Life Books, Alexandria, Virginia (1995) ISBN 0-8094-9104-4

- Pittman, Holly (1984). Art of the Bronze Age: southeastern Iran, western Central Asia, and the Indus Valley. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870993657.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title=

- Potts, Daniel T.: The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State, Cambridge University Press (1999) ISBN 0-521-56496-4 and ISBN 0-521-56358-5

- McAlpin, David W., Proto Elamo Dravidian: The Evidence and Its Implications, American Philosophy Society (1981) ISBN 0-87169-713-0

External links[edit]

- Lengua e historia elamita, by Enrique Quintana

- Hamid-Reza Hosseini, Shush at the foot of Louvre (Shush dar dāman-e Louvre), in Persian, Jadid Online, 10 March 2009, [3].

Audio slideshow: [4] (6 min 31 sec)

29°54′N 52°24′E / 29.900°N 52.400°E

Category:States and territories established in the 3rd millennium BC