User:Slp1/sandbox

| Our Lady of Medjugorje | |

|---|---|

Statue of Our Lady of Medjugorje | |

| Location | Medjugorje, Bosnia and Herzegovina and a number of other locations |

| Date | 24 June 1981 – ongoing |

| Witness |

|

| Type | Marian apparition |

| Approval | Pending decision by the Holy See |

| Shrine | Medjugorje |

Our Lady of Medjugorje (Croatian: Međugorska Gospa), also called Queen of Peace (Croatian: Kraljica mira) and Mother of the Redeemer (Croatian: Majka Otkupiteljica), is the title given to the "visions" of the Blessed Virgin Mary which allegedly began in 1981 to six Herzegovinian teenagers in Medjugorje, Bosnia and Herzegovina (at the time in SFR Yugoslavia). The visionaries are: Ivan Dragičević, Ivanka Ivanković, Jakov Čolo, Marija Pavlović, Mirjana Dragičević and Vicka Ivanković and ranged in age from ten to sixteen years old at the time of the first apparition.

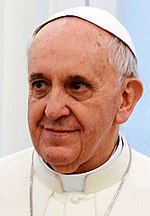

There have also been continued reports of the visionaries seeing and receiving messages from the apparition of Our Lady (Gospa) during the years since. The seers often refer to the apparition as the "Gospa", which is a Croatian archaism for lady. On May 13, 2017, a papal response came when Pope Francis declared that the original visions reported by the teenagers are worth studying in more depth, while the subsequent continued visions over the years are, in his view, of dubious value.[1] He went on to say that there are people who go there, convert, find God and their lives change. He said that this is a spiritual and pastoral fact that cannot be denied.[2] As a pastoral initiative, after considering the considerable number of people who go to Medjugorje and the abundant fruits of grace that have sprung from it,[3] the ban on officially organized pilgrimages was lifted by the Pope in May 2019. This was made official with the celebration of a youth festival among pilgrims and Catholic clergy in Medjugorie for five days in August 2019.[4] However this was not to be interpreted as an authentication of known events, which still require examination by the Church.[3]

Background[edit]

Political situation[edit]

In the summer of 1941, the Croat Ustaše killed hundreds of women and children from the village of Prebilovci, Herzegovina, and Orthodox monks from the monastery of Žitomislići by throwing them into the Golubinka pit, near Šurmanci. Forty years later, in June 1981, the Orthodox community led a commemoration of the event. "The location where the Šurmanci massacre took place lies precisely on the opposite side of the mountain where the current apparitions began ...only four days after the ceremonies took place."[5]

Religious situation[edit]

When the area came under Ottoman control in the late fifteenth century it lost any effective diocesan administration and pastoral care for the resident Catholics fell to the Franciscan friars who remained. By the latter part of the nineteenth century Bosnia and Herzegovina became part of Austria-Hungary, and in 1881 Pope Leo XIII took steps to establish dioceses (1881) and appoint local bishops, as had been done elsewhere. This included transferring parishes administered by the Franciscans to diocesan clergy. A smooth transition was inhibited by both a lack of sufficient diocesan clergy and more particularly by the resistance of the friars to the divestment of their parishes. This would have entailed the loss of both income to support their monasteries, and their hard-earned status as community leaders.[6] They therefore encouraged popular opposition to diocesan parish takeovers.[citation needed]

In 1975 a decree by Pope Paul VI, Romanis Pontificibus, ordered that Franciscans to withdraw from most of the parishes in the Diocese of Mostar-Duvno, retaining 30 and leaving 52 to the diocesan clergy. In the 1980s the Franciscans still held 40 parishes under the direction of 80 friars.[7]

The Mostar Cathedral of Mary, Mother of the Church was completed in the summer of 1980 and consecrated on September 14, 1980 by Cardinal Franjo Šeper, Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. In order to create the cathedral parish it was decided to split the parish of SS. Peter and Paul. The Franciscans objected to this as being unfair.[citation needed]

In the 1980s there was a boom of Marian apparitions in Europe, especially in Ireland and Italy. Chris Maunder connects these apparitions, including those in Medjugorje, with the anti-communist movement in Eastern Europe that led to the downfall of communism.[8]

Initial events[edit]

According to teenagers involved, on 24 June 1981 around 4pm, fourteen-year-old Ivanka Ivanković, whose mother had died the previous May, and her friend Mirjana Dragičević were returning to the village, having gone for a walk. Ivanka noticed the silhouette of a woman on nearby Mount Podbrdo which she immediately took to be the Madonna. She drew this to Marija's attention, but her friend scoffed at the idea as being unlikely and they continued on their way. They then met Milka Pavlovic, who asked them to help bring in the sheep, so the three returned to the nearby hill, where all three saw the apparition. They were then joined by their friends Vicka Ivanković, Ivan Dragičević and Ivan Ivankovic. Ivan Dragicevic was frightened and left; the others followed. All of them later said they saw the same apparition.[citation needed]

The next day Ivanka Ivankovic, Mirjana Dragicevic, Vicka Ivankovic, and Ivan Dragicevic returned to the site. Ivan Ivankovic did not accompany them. As Milka Pavlovic's mother kept the twelve-year-old to help her in the garden, Vicka Ivankovic brought along Milka's sister, Marija Pavlovic, and ten-year-old Jakov Colo. Milka experienced no further apparitions. The six seers told Franciscan friar Father Jozo Zovko that they had seen the Virgin Mary at Medjugorje. Zovko was the parish priest at St. James Church in Medjugorje.[citation needed]

Fr. Tomislav Vlašić became a spiritual guide of the seers and was conducting the Chronicle of Apparitions (Kronika ukazanja). [citation needed] Ivanka Ivankovic,Ivan Dragičević and Vicka Dragičević, claimed that Our Lady told her biography between January and May 1983.[citation needed] She claims to have had regular apparitions until May 7, 1985, and that since then the apparitions occur only once a year. She claims the tenth secret was given to her by Gospa.

Government and Catholic church response[edit]

Yugoslav government officials condemned the reports as "clerical-nationalist" conspiracy on the part of Croat extremists.[9] Although the Yugoslav authorities initially regarded the events as little more than a conspiracy on the part of Bosnian Croat nationalists, gradually "the cash-strapped Yugoslav authorities realized the commercial potential of Mudjugorje."[9] During the 1980s, Medjugorje was visited by a million pilgrimages on average.[10] Journalist Inés San Martin described Medugorje as "barely more than a village in 1981, [that] has since grown to become one big hotel, with restaurants and religious shops being the only commercial activity at hand. Some of its detractor say that it's a tourist trap."[11] Bishop Pavao Žanić of Mostar defended the seers from the communist authorities that tried to suppress the cult of Our Lady of Medjugorje,[citation needed] but at the same time avoided recognizing the apparitions as authentic. He informed the Pope about the events in September 1981.[citation needed] Zanic, in the beginning, was sympathetic to the young visionaries, but subsequently changed his mind and became the main critic and opponent of the Medjugorje apparitions.[12] Žanić was quickly disillusioned with the phenomenon after three of the seers claimed that the Madonna supported the Herzegovinian Franciscans in their pretension for parishes in the Diocese of Mostar-Duvno, an old dispute between them and the diocese known as the Herzegovina Affair.[13] He became skeptical towards the apparitions after it was alleged that the apparition accused him of the disorder in Herzegovina that existed between the Franciscans and the diocesan clergy and defended the two Franciscans who refused to leave their parishes as requested by the Papal decree Romanis Pontificibus.[citation needed] The Franciscans used the apparitions to promote their interests, claiming that they come from the Madonna, while the bishop claimed that they were a product of Franciscan manipulation.[14] Žanić accused the Franciscans of manipulating the seers, forbade pilgrimages and transferred the spiritual director of the seers Tomislav Vlašić, whose sexual scandal wasn't known yet at the time.[citation needed] In August 1984, Vlašić was replaced by Franciscan friar Slavko Barbarić,[15] who, unbeknownst to Žanić, was already working in Medjugorje.[citation needed] Žanić's successor as bishop of the Diocese of Mostar-Duvno Ratko Perić also stated that he believed that the apparitions were false. In particular, he stated that the Mary described by the children differs from accepted Marian behaviour, messages, actions, and an unfulfilled signs.[16]

In January 1982, Žanić established the first of two commissions for the investigation of the apparitions. The first commission, made up of four members was active from 1982 to 1984.[citation needed] In February 1984 Žanić expanded the initial commission to fifteen members. It included nine professors from various theological faculties and two psychiatrists.[citation needed] This second commission examined Fr. Tomislav Vlašić's Chrinicles and Vicka's diaries. The Chronicles and diaries were found incredible, with records kept irregularly, entered subsequently, and some parts of Vicka's diaries were forged.[citation needed] In May 1986, the Commission declared that it could not establish that the events in Medjugorje were of a supernatural character.[citation needed]

Medjugorje had become a global phenomenon, while Žanić's authority was undermined by the supporters of the phenomenon.[14] In January 1987, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, suggested that the matter be referred from the local ordinary to the Yugoslav Bishops Conference, which agreed with the second commission and ruled "non constat de supernaturalitate", stating in April 1991, that: "(o)n the basis of studies it cannot be affirmed that supernatural apparitions and revelations are occurring." [citation needed]

The Conference had instructed that pilgrimages should not be organized to Medjugorje on the supposition of its being supernatural, which ruling remained in effect.[17] In its declaration the commission noted that thousands of pilgrims come to Medujorje and were in need of pastoral care.[citation needed]

During and after the Bosnian War[edit]

In 1991 the country of Yugoslavia was dissolved, and the constituent republics declared their independence.[citation needed] During the Bosnian War, profits from Medjugorje were channeled to fund the war efforts of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia and its military, the Croatian Defence Council. On one occasion, a businessman from the United Kingdom used the money he apparently collected for orphans to fund the Croat military.[18] Serbs and Muslims who saw the "Gospa" as a symbol of extreme Croat nationalism called her the "Ustasha Virgin".[9] The number of pilgrimages to continued after the end of Bosnian War in 1995.[10]

In 1993 Bishop Žanić retired. In April 1995, during the Bosnian War, his successor, Bishop Ratko Perić, and Perić's secretary, were abducted and beaten by Croat militiamen in a local Franciscan chapel. They were held for eight hours until rescued by UN peacekeepers and the Mayor of Mostar.[9] In October 1997, Bishop Perić, in response to a letter, expressed his personal opinion that the events alleged at Medjugorje were no longer non constat de supernaturalitate (that their supernatural nature is not established) but constat de non supernaturalitate (it is not of a supernatural nature).[citation needed]

Both Bishop of Mostar Pavao Zanic and his successor Ratko Peric expressed serious reservations concerning the alleged apparitions. According to Peric, both Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI supported the judgments of the local bishops.[19] The pope's private secretary Stanisław Dziwisz stated that the Pope had entrusted the whole matter to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and thereafter maintained "a prudent distance." [citation needed] However, according to Why he is a Saint, the book making the case for his canonization, Pope John Paul II allegedly confided to others that he felt the events at Medjugorje were genuine. The Vatican has never confirmed those statements.[20][21]

Others were skeptical. Marian expert and journalist Donal Foley says that, “sadly, the only rational conclusion about Medjugorje is that it has turned out to be a vast, if captivating, religious illusion”.[22] Foley attributed the popularity of the Medjugorje cult to the fact that Medjugorje may appeal to Catholics confused by changes after the Second Vatican Council.[citation needed]

According to local priest and theologian Ivo Sivric reports of mysterious lights on the hill could easily be explained by illusions produced by atmospheric conditions, or fires that were lit by local youths.[23][24]

Raymond Eve, a professor of sociology, in the Skeptical Inquirer wrote:

I acknowledge that the teenagers' initial encounters with the Virgin may well have been caused by personal factors. For example, Ivanka, who was the first to perceive a visitation, had just lost her natural mother. The perception of apparitional experiences spread rapidly among her intimate peer group. ...The region's tension and anxiety likely exacerbated this contagion process and the need to believe among the youthful protagonists.[25]

Skeptical investigator Joe Nickell has noted that there are a number of reasons for doubting the authenticity of the apparitions such as contradictions in the stories. For example, on the first sighting, the teenagers claimed they had visited Podbrdo Hill to smoke. They later retracted this, claiming they had gone to the hill to pick flowers. According to Nickell there is also a problem of the "embarrassingly illiterate" nature of the messages.[23]

In 1997, the Hercegovacka Banka was founded "by several private companies and the Franciscan order, which controls the religious shrine in Medjugorje, a major source of income, both from pilgrims and from donations by Croats living abroad."[26] Located in Mostar, the bank has branches in several towns. In 2001, the bank was investigated for possible ties to Bosnian Croat separatists attempting to forge an independent mini-state in Croat areas of Bosnia. Tomislav Pervan, OFM was a member of the bank board of supervisors, as well as former officers of the Croatian Defence Council.[27]

2000 to present[edit]

Bishop Peric visited Rome in 2006 and reported that in his discussion with Pope Benedict XVI regarding the Medjugorje phenomenon, the pope said, "We at the congregation always asked ourselves how can any believer accept as authentic apparitions that occur every day and for so many years?"[28]

In 2009, Pope Benedict defrocked Tomislav Vlašić, the spiritual director of the alleged seers.[29]

In an interview in May 2017, Pope Francis commented on the findings of the commission headed by Cardinal Camillo Ruini saying that the report said of the initial apparitions that they "need to continue being studied" and expressed doubts in the later apparitions. He also expressed his own suspicion towards the apparitions saying he prefers "the Madonna as Mother, our Mother, and not a woman who's the head of the telegraphic office, who sends a message every day".[30][31]

Ruini Commission[edit]

On 17 March 2010, the Holy See announced that, at the request of the bishops of Bosnia Herzegovina, it had established a commission, headed by Cardinal Camillo Ruini, to examine the Medjugorje phenomenon.[32][33] Other prominent members of the commission included Cardinals Jozef Tomko, Vinko Puljić, Josip Bozanić, Julián Herranz and Angelo Amato, psychologists, theologians, mariologists and canonists. The commission was to "collect and examine all the material", and publish a "detailed report" based on its findings.[30] It was tasked to evaluate the alleged apparitions and to make appropriate pastoral recommendations for those pilgrims who continued to go to Medjugorje despite the ban on official pilgrimages. The Commission was active until 17 January 2014.

The Ruini Commission made a distinction between the first appearances from 24 June 1981 until 3 July 1981, with reportedly 13 votes in favor of those apparitions being of "supernatural" origin, one vote against, and an expert with a suspensive vote. Regarding the rest of the apparitions, from July 1981 onwards, the Commission found them to be influenced by heavy interference caused by the conflict between the Franciscans and the diocese over the redistribution of parishes. The Commission deemed later visions to be "pre-announced and programmed", and they continued despite the seers stating they would end.[30]

Regarding the pastoral fruits of Medjugorje, the Commission voted in two phases. In the first phase, they disregarded the behavior of the seers and voted six in favor of the positive outcome (including three experts), seven stating they are mixed (including three experts) with most being positive, and other three experts stating the fruits are a mix of positive and negative. In the second phase, taking into consideration the behavior of the seers, twelve members (including four experts) stated they cannot express their opinion, and other two members voted against the supernatural origin of the phenomenon.[30]

The Ruini Report was completed in 2014,[34][35] and was viewed with some reservations by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which expressed doubts regarding the apparitions.[30] Cardinal Gerhard Ludwig Müller, who headed the Congregation at the time, said in April 2017 regarding Medjugorje, that "pastoral questions" cannot be separated "from questions of the authenticity of apparitions".[36]

In 2017, around two million people from more around eighty countries from all over the world visited Medjugorje.[citation needed] The Archbishop reported to the Pope in the summer of 2017.[37]

Like to the Pope John Paul II, many statements affirmative towards Medjugorje were ascribed to Pope Benedict XVI while he was still a cardinal, which he dismissed as "mere fabrications".[38] In February 2017 Pope Francis named Polish Archbishop Henryk Hoser as a special envoy to "acquire more in-depth knowledge of the pastoral situation in Medjugorje" and “above all, the needs of the faithful who come to pilgrimage” to “suggest any pastoral initiatives for the future.”[39] On May 12, 2019, Pope Francis authorized pilgrimages to Medjugorje considering the "considerable flow of people who go to Medjugorje and the abundant fruits of grace that have sprung from it." While pilgrimages can now be officially organized by dioceses and parishes, the permission did not address still outstanding doctrinal questions relating to the authenticity of the alleged visions.[40] As a result, the Apostolic Visitor "will have greater facility—together with the bishops of these places—of establishing relations with the priests who organize these pilgrimages” to ensure that they are “sound and well prepared."[41] The first sanctioned event was the Thirtieth Annual Youth Festival, which took place from August 1-6 2019. During the pilgrimage, approximately 50,000 young Catholics from all over the world took part.[42] On 31 May 2018 Pope Francis nominated Archbishop Hoser a second time “as special apostolic visitor for the parish of Medjugorje” with the mandate lasting for “an undefined period..." at the discretion of the Pope. Archbishop Hoser was appointed by Pope Francis to evaluate the quality of pastoral care people were receiving at Medjugorje.[39] The Ruini Commission had recommended that the town's parish Church of St. James be made a pontifical shrine with Vatican oversight. From a pastoral perspective, this would both recognize the devotion of those who travel to Medjugorje and "ensure that 'a pastor and not a travel agency' is in charge of what happens there".[43]

According to Marshall Connolly of the media company California Network, what Hoser witnessed convinced the archbishop that something genuine has happened. Hoser told the Polish Catholic news agency, KAI, "All indications are that the revelations will be recognized, perhaps even this year." He added, "Specifically, I think it is possible to recognize the authenticity of the first apparitions as proposed by the Ruini commission."[citation needed]

Henryk Hoser, the apostolic visitator in Medjugorje, stated in July 2018 that the mafia had penetrated the pilgrimage site, specifically the Neapolitan mafia – the Camorra. According to the Neapolitan newspaper Il Mattino in Naples, magistrates are investigating Camorra ties to a pilgrimage business, three hotels, guide services, and souvenir vendors in Medjugorje.[44]

On June 25, 2020 Reuters reported that the travel restrictions had caused a marked decrease in pilgrimages, down from over 100,000 per year, along with a loss in revenue for local businesses.[45]

See also[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Harris, Elise (2017-05-13). "Pope Francis: I am suspicious of ongoing Medjugorje apparitions". Catholic News Agency (CNA). Retrieved 2018-03-18.

- ^ "Pope Francis' opinion on the Medjugorje apparitions". Rome Reports. 2017-05-13. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ^ a b "Pope authorizes pilgrimages to Medjugorje - Vatican News". www.vaticannews.va. 2019-05-12. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- ^ Luxmoore, Jonathan (2019-08-07). "Vatican confirms Medjugorje approval by joining youth festival". Catholic News Service. Retrieved 2020-07-06.

- ^ Herrero, Juan A. (1999). "Medjugorje: Ecclesiastical Conflict, Theological Controversy, Ethnic Division". In Joanne M. Greer, David O. Moberg (ed.). Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion. Stamford, Connecticut: JAI Press. p. 142. ISBN 0762304839.

- ^ Herrero, p. 143.

- ^ Vjekoslav Perica (2004). "The Apparitions in Herzegovina and the Yugoslav Crisis of the 1980s", Balkan Idols: Religion and Nationalism in Yugoslav States. Oxford University Press. pp. 117–118

- ^ Maunder 2016, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d McLaughlin, Daniel. "Little peace or tranquility at Bosnian village with murderous history near Medjugorje", The Irish Times, July 6, 2011

- ^ a b Apolito 2005, pp. 3–4.

- ^ San Martin, Inés. "As debate rages over Medjugorje, maybe a place of prayer is enough", Crux, September 23, 2016

- ^ Gaspari, Antonio (November 1996). "Medjugorje Deception or Miracle?". Inside the Vatican. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ Maunder 2016, p. 160.

- ^ a b Maunder 2016, p. 161.

- ^ Maunder 2016, pp. 160–161.

- ^ "Local bishop: 'The Madonna has not appeared in Medjugorje'". www.catholicnewsagency.com.

- ^ "Biskupije Mostar-Duvno i Trebinje-Mrkan | Dioeceses Mandetriensis-Delminiensis et Tribuniensis-Marcanensis". Cbismo.com (in Croatian). Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ Maunder 2016, p. 166.

- ^ "Medjugorje apparition claims are divisive", Catholic World News, July 4, 2006

- ^ Thavis, John. "Medjugorje 25 years later: Apparitions and contested authenticity", CNS, July 3, 2006

- ^ Oder, Slawomir Appointed the Postulator of the cause of beautification and canonization of Pope John Paul II (2010). Why He Is A Saint. New York, NY: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc. pp. 167–169. ISBN 978-0-8478-3631-4.

- ^ "Medjugorje's Mystery", Catholic News Service, June 25, 2006

- ^ a b Nickell, Joe. (1993). Looking for a Miracle: Weeping Icons, Relics, Stigmata, Visions & Healing Cures. Prometheus Books. pp. 190-194. ISBN 1-57392-680-9

- ^ The hidden side of Medjugorje : a new look at the "apparitions" of the Virgin Mary in Yugoslavia. Ivo Sivric. Saint-François-du-Lac, Québec: Psilog Inc. 1989-. ISBN 2-921010-01-1. OCLC 20987005.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Politicizing the Virgin Mary: The Instance of the Madonna of Medjugorje". Csicop.org. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- ^ "Authorities seize 'corrupt' Bosnian bank", The Guardian, April 6, 2001

- ^ Grandits, Hannes. "The Power of “Armchair” Politicians: Ethnic Loyalty and Political Factionalism among Herzegovinian Croats", The New Bosnian Mosaic. Identities, Memories and Moral Claims, (X. Bougarel, G. Duijzings, E. Helms, eds.), Routledge, New York, 2016, p. 113

- ^ Thavis, John. "Medjugorje 25 years later: Apparitions and contested authenticity", CNS, July 3, 2006

- ^ Latal 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Tornielli.

- ^ Harris.

- ^ "Holy See confirms creation of Medjugorje Commission". Catholic News Agency (ACI Prensa). 17 March 2010.

- ^ "Medjugorje Commission Announced", Catholic News Service, March 28, 2010

- ^ "Commission to submit study on Medjugorje". News.va. 2014-01-18. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ Harris, Elise (12 May 2019). "Pope okays pilgrimage to Medjugorje, says apparitions 'need study'". CRUX. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ eKai.

- ^ Medjugorje; the findings of the Ruini report 17 May 2017, www.lastampa.it, accessed 21 July 2020

- ^ Nacional.

- ^ a b "Pope's envoy to Medjugorje begins his ministry". Vatican News. 21 July 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Menichetti, Massimiliano. "Pope authorizes pilgrimages to Medjugorje", Vatican News Service, May 12, 2019

- ^ O'Connell, Edward. "Pope Francis authorizes the organization of pilgrimages to Medjugorje", America, May 12, 2019

- ^ Merlo, Francesca. "30th annual Youth Festival opens in Medjugorje", Vatican New Service, August 2, 2019

- ^ Wooden, Cindy. CNS, May 18, 2017

- ^ "Hoser, 'Medjugorje target of the Mafia'", La Stampa, July 10, 2018

- ^ Sito-Sucic, Daria (2020-06-25). "Coronavirus keeps pilgrims away from Bosnian shrine". Reuters. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

References[edit]

Books[edit]

- Bulat, Nikola (2006). Istina će vas osloboditi [The Truth will set you free] (in Croatian). Mostar: Biskupski ordinarijat Mostar.

- Emmanuel, Sister (1997). Medjugorje, the 90's - The Triumph of the Heart. Goleta, CA: Queenship Publishing Company. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-1-7359106-0-4.

- Kutleša, Dražen (2001). Ogledalo pravde [Mirror of Justice] (in Croatian). Mostar: Biskupski ordinarijat Mostar.

- Maunder, Chris (2016). Our Lady of the Nations: Apparitions of Mary in 20th-Century Catholic Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198718383.

- Pavičić, Darko (2019). Međugorje: prvih sedam dana: cijela istina o ukazanjima od 24. lipnja do 3. srpnja 1981 [Medjugorje: the first seven apparitions: the whole truth on apparitions from 24 June to 3 July 1981] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Pavičić izdavaštvo i publicistika. ISBN 9789534862001.

- Perica, Vjekoslav (2002). Balkan Idols: Religion and Nationalism in Yugoslav States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Weible, Wayne (1989). Medjugorje The Message. Paraclete Press. ISBN 1-55725-009-X.

- Žanić, Pavao (1990). La verita su Medjugorje [The truth about Medjugorje] (in Italian). Mostar: Diocese of Mostar-Duvno.

- Soldo, Mirjana (2016). My Heart Will Triumph. Catholic Shop Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9978906-0-0.

Journals and magazines[edit]

- Czernin, Marie (2004). "Medjugorje and Pope John Paul II – An Interview with Bishop Hnilica". Germany: Politik und Religion (PUR).

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - Perić, Ratko (2012). "Međugorske stranputice" [The Medjugorje side roads]. Službeni vjesnik (in Croatian) (3): 97–102.

- Zovkić, Mato (1993). "Problematični elementi u fenomenu Međugorja" [The problematic elements in the Medjugorje phenomenon]. Bogoslovska Smotra (in Croatian). 63 (1–2): 76–87.

News articles[edit]

- "Autentyczność objawień w Medziugorie". eKai (in Polish). 11 April 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Garrison, Greg (3 July 2012). "Visionary from Medjugorje says Virgin Mary is aware of economic crisis". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- Garrison, Greg (17 July 2012). "Could an Alabama shrine become the next Catholic pilgrimage site?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- Harris, Elise (13 May 2017). "Pope Francis: I am suspicious of ongoing Medjugorje apparitions". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Latal, Srecko (28 July 2009). "Bosnia: Medjugorje Priest Defrocked". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- "OVO JE VILA VIDJELICE IZ MEĐUGORJA PRED KOJOM JE BETONIRANA PLAŽA, A ZA KOJU ONA KAŽE 'KAKVA KUĆA, KOJA PLAŽA?' Sedam dana luksuza naplaćuje 25.000 kn". Jutarnji list. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- "PROGONSTVO FRA ZOVKA: Zašto je Papa prognao fra Zovka iz Međugorja" [Exile of Fr. Zovko: Why Pope exiled Fr. Zovko from Medjugorje]. Nacional (in Croatian). 18 October 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Rašeta, Boris; Mahmutović, Denis (5 August 2019). "Vidjelice iz Međugorja imaju milijune - hoteli, vile, auti..." Express. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- Tornielli, Andrea (17 May 2017). "Medjugorje; the findings of the Ruini report". La Stampa. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- "Pope authorizes pilgrimages to Medjugorje". Vatican News. 12 May 2019. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- "Pope's envoy to Medjugorje begins his ministry". Vatican News. 21 July 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

Websites[edit]

- "Archbishop reveals a surprise about Medjugorje". Catholic Online. 23 August 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- "Approval by the Bishop". The Fatima Center. 1930. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- "Detailed Description of Our Lady, the Queen of Peace, as she appears in Medjugorje". Medjugorje - Place of Prayer and Reconciliation. Retrieved 8 Nov 2020.

- "Medjugorje 'visionary' says monthly apparitions have come to an end". Angelus News. 2020-03-18. Retrieved 2020-10-05.

- Majdandžić-Gladić, Snježana (2017). "O međugorskim zelotima ili Gospom protiv Gospe" [On the zealots of Medjugorje or with Gospa against Gospa]. Vjera i djela (in Croatian). Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Arcement, Katherine (13 October 2017). "Our Lady of Fatima: The Virgin Mary promised three kids a miracle that 70,000 gathered to see". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- "Pope authorizes pilgrimages to Medjugorje - Vatican News". www.vaticannews.va. 2019-05-12. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- Harris, Elise (2017-05-13). "Pope Francis: I am suspicious of ongoing Medjugorje apparitions". Catholic News Agency (CNA). Retrieved 2018-03-18.

- "Pope Francis' opinion on the Medjugorje apparitions". Rome Reports. 2017-05-13. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ""The Gospels According to Christ? Combining the Study of the Historical Jesus with Modern Mysticism", Daniel Klimek". Glossolalia.sites.yale.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-11. Retrieved 2013-04-01.

- Luxmoore, Jonathan (2019-08-07). "Vatican confirms Medjugorje approval by joining youth festival". Catholic News Service. Retrieved 2020-07-06.

- "Vatican Mission Begins in Medjugorje! Archbishop Hoser's Historic Mass". Medjugorje Miracles. 23 July 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- "Virus deters Catholic pilgrims from Medjugorje". CRUX. AP Archive. March 15, 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- "What Pope's Envoy concluded in Medjugorje?". 03 April 2017. 21 July 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

External links[edit]

- Shrine of Our Lady of Medjugorje – Official Website (in English)

Category:Catholic pilgrimage sites

Category:Catholic Church in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Category:Čitluk, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Category:Marian apparitions