User:Shannon1/Sandbox 3

| Feather River | |

|---|---|

The Feather River above its confluence with the Bear River | |

Map of the Feather River drainage basin, with the artificially connected Butte Creek and Sutter Basin indicated in yellow | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | North Fork Feather River |

| • location | Lassen Volcanic National Park, Plumas County |

| • coordinates | 40°21′47″N 121°27′05″W / 40.36306°N 121.45139°W[1] |

| • elevation | 5,436 ft (1,657 m)[2] |

| 2nd source | Middle Fork Feather River |

| • location | Sierra Valley, Plumas County |

| • coordinates | 39°48′49″N 120°22′46″W / 39.81361°N 120.37944°W[3] |

| • elevation | 4,872 ft (1,485 m)[4] |

| Source confluence | Lake Oroville source_confluence_location = Upstream of Oroville Dam |

| • coordinates | 39°32′14″N 121°29′00″W / 39.53722°N 121.48333°W |

| • elevation | 902 ft (275 m)[5] |

| Mouth | Sacramento River |

• location | Verona, Sutter County |

• coordinates | 38°47′08″N 121°37′17″W / 38.78556°N 121.62139°W[6] |

• elevation | 26 ft (7.9 m)[6] |

| Length | 73 mi (117 km)[7] |

| Basin size | 6,200 sq mi (16,000 km2)[8] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Nicolaus |

| • average | 8,537 cu ft/s (241.7 m3/s)[9] |

| • minimum | 150 cu ft/s (4.2 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 357,000 cu ft/s (10,100 m3/s) |

The Feather River is a major river in Northern California and is the principal tributary of the Sacramento River. The river is fed by several forks that drain a large area of the northern Sierra Nevada before combining at Lake Oroville, the reservoir formed by Oroville Dam. The Feather River proper then flows southwards through the Sacramento Valley from Oroville to join the Sacramento River at Verona, about 20 miles (32 km) northeast of downtown Sacramento. The main stem of the Feather River is 73 miles (117 km) long; measured to the head of its longest tributary, it is nearly 215 miles (346 km) long.[7] The Feather River drainage basin includes parts of nine California counties; the main stem of the river flows through Butte, Yuba and Sutter counties. The Feather River is the only river system that cuts across the Sierra Nevada, with some of its tributaries originating east of the Sierra Crest in the Diamond Mountains.[10]: 133

Historically, the Feather River basin was primarily Maidu territory although the Paiute and Washoe also used the area for hunting. The river and its tributaries were a major center of mining during the California Gold Rush in the 1850s and were settled by Europeans soon afterward. The river was a major transporation corridor across the northern Sierra for Native Americans and early explorers, and in 1909 the Feather River Route, following the North Fork canyon, became the second railroad to cross the Sierra Nevada. The Feather River and its tributaries have experienced significant environmental damage from mining, timber harvesting, livestock grazing, and other economic activities in the decades since the gold rush era, with high turbidity being a continuing concern for its impacts on fish habitat and flooding.

The Feather is one of the largest rivers in California by volume, with an average annual flow exceeding 7 million acre feet (8.65 billion m3).[11] The river's water has been used for irrigation and mining in the Sacramento Valley since the mid-19th century, and for hydroelectricity generation since the early 20th century. As the primary source of water for the California State Water Project, the Feather provides water for the San Joaquin Valley and Southern California.

Geography[edit]

The Feather River drainage basin is almost 6,200 square miles (16,000 km2) in size.[8] The east side (upstream part) of the basin consists of rugged mountains, mostly in the Sierra Nevada but with small portions in the Cascade Range. The Feather River headwaters consist of the 3,550 square miles (9,200 km2) upstream of Lake Oroville, representing about 57 percent of the entire drainage basin.[8] Prior to the damming of the river in 1968, the North and Middle Forks joined just above Oroville near Bidwell's Bar to form the Feather River; the West Branch flowed into the North Fork, and the South Fork was a tributary of the Middle Fork.[7]

With the exception of the 10,457-foot (3,187 m) Lassen Peak volcano at the northern edge of the basin, the highest peaks in the upper Feather top out at elevations of 7,000 to 8,000 feet (2,100 to 2,400 m).[12]: 8 Precipitation ranges from 70 inches (1,800 mm) on west-facing slopes to 12 inches (300 mm) on the drier eastern side.[13]: 5 The Feather headwaters include almost all of Plumas County and portions of Butte, Sierra, Shasta and Lassen counties.[10]: 133 The upper Feather basin generally consists of heavily forested, high elevation plateaus and ridges, separated by deep canyons cut by the various forks of the Feather River. The part of the drainage east of the Sierra Crest is more sparsely forested and contains large areas of sagebrush.[10]: 133 There are also several large intermontane valleys, including the Sierra Valley, American Valley, and Indian Valley. These valleys support alluvial meadow systems that are important to regulating stream flows.[13]: 5 The Sierra Valley, 4,850 feet (1,480 m) above sea level and encompassing 120,000 acres (49,000 ha), is the largest alpine meadow ecosystem in the United States.[10]: 133

About 80 percent of the upper Feather is public land, with most of that in the Plumas National Forest and a small part of Lassen National Forest.[14]: 3 The timber industry has historically been predominant, though its economic importance has declined since the late 20th century, with the outdoor recreation and service industries increasing in importance. The high mountain valleys are used mainly for livestock grazing. Agriculture is limited due to the cold, snowy winters, with the main crops being alfalfa hay and grain.[14]: 6 The area is sparsely populated, with an average of 8.2 persons per square mile (3.2 persons/km2).[10]: 137

The drainage basin below Oroville is mostly in the low-lying Sacramento Valley, and is almost entirely developed for agriculture. Not including tributaries to the lower Feather, this area encompasses 774 square miles (2,000 km2), or 12 percent of the Feather River basin.[7] The vast majority of lands in the lower basin are privately owned. The largest population centers in the Feather River basin, which include Oroville, Palermo, Gridley, and Marysville–Yuba City, are all located on or near the lower Feather River. As of 2010, more than 100,000 people lived in this region, which includes parts of Butte, Yuba and Sutter Counties.[15]: 140 Hydrology is heavily modified, with most of the major rivers regulated by upstream dams, and about 1,266 miles (2,037 km) of canals drawing water for agricultural irrigation.[15] The main tributaries of the lower Feather River are the Yuba River, which drains 1,324 square miles (3,430 km2), and the Bear River, which drains 361 square miles (930 km2).[8] The Yuba and Bear rivers also originate in the high Sierra; the Yuba headwaters reach even higher elevations than the Feather headwaters, with numerous 8,000-to-9,000-foot (2,400 to 2,700 m) peaks in the Donner Pass area.[citation needed] In addition to Butte, Yuba and Sutter counties, the Yuba and Bear Rivers also drain portions of Sierra, Placer and Nevada counties.[16][17]

North Fork[edit]

The North Fork is the largest tributary of the Feather River by volume. It originates at Feather River Meadows in far western Plumas County just outside of Lassen Volcanic National Park, and flows southeast to the large open valley of Big Meadows, home to Chester and the Lake Almanor reservoir.[18][19] At 25,000 acres (10,000 ha), Lake Almanor has the greatest area of any lake in the Feather River basin (though Lake Oroville contains more water). Below Canyon Dam, it turns southwest and flows through a steep narrow gorge, where it passes through a cascade of hydroelectric power stations nicknamed the "Stairway of Power",[20] and enters Butte County near Cresta.[21][22] East of Paradise, it enters the upper reaches of Lake Oroville, where the lower 15 miles (24 km) of the river form the northern arm of the lake.[22] The North Fork canyon is used by the Feather River Route of the Union Pacific Railroad, as well as SR 70 (Feather River Scenic Byway).[22]

The North Fork is approximately 100 miles (160 km) long, or 111 miles (179 km) including its headwater tributary, Rice Creek.[7] The total drainage basin is 2,240 square miles (5,800 km2), or nearly two-thirds of the total drainage area above Lake Oroville.[7] The average discharge, as measured near Pulga, was 3,384 cubic feet per second (95.8 m3/s) for the period 1967 to 1983.[23]

East Branch[edit]

The East Branch of the North Fork begins as several streams draining the far eastern reaches of Plumas County. Indian Creek, 50 miles (80 km) long,[7] begins in the Diamond Mountains east of the Sierra Crest, making it one of only two Sierra streams to breach the crest (the other being the Feather's Middle Fork).[13]: 5 The East Branch proper forms at the confluence of Indian Creek with Spanish Creek at Paxton, north of Quincy. From there the river flows due west through a rugged canyon to join the North Fork at French Bar, about 15 miles (24 km) downstream from Canyon Dam.

Although the main stem of the East Branch is only 18 miles (29 km) long, the entire East Branch system is 89.3 miles (143.7 km) long when measured to the head of Last Chance Creek (the longest tributary of Indian Creek).[7] The East Branch drains 1,028 square miles (2,660 km2),[7] and its average discharge near the mouth was 1,040 cubic feet per second (29 m3/s) for the period 1950 to 1983.[24] Combined with the lower North Fork, the East Branch system is also the longest tributary of the Feather River, with water flowing 215 miles (346 km) from the head of Last Chance Creek to the confluence of the Feather and Sacramento Rivers.[7]

West Branch[edit]

The West Branch originates at shallow, marshy Snag Lake in northeastern Butte County, about 5 miles (8.0 km) to the east of Butte Meadows.[25] The river flows west of and roughly parallel to the lower section of the North Fork below Lake Almanor. Its drainage basin is at a lower elevation than that of the North Fork, though it is also rugged and heavily forested. For most of its length, the river flows southward through a gorge, passing close to the east side of Magalia and Paradise before emptying into the North Fork arm of Lake Oroville.[26][27] The West Branch is 46.3 miles (74.5 km) long and drains approximately 168 square miles (440 km2).[7] The average discharge near the mouth was 349 cubic feet per second (9.9 m3/s) for the period 1930 through 1963.[28]

Middle Fork[edit]

The Middle Fork begins in the Sierra Valley, at the outlet of the Sierra Valley Channels, an extensive network of wetlands in eastern Plumas County.[29] It flows generally west, through several small towns including Portola, Mohawk and Sloat.[22] Upstream of Sloat, the Middle Fork, like the North Fork, forms part of the Feather River Route and SR 70 corridor.[22] Below that point, the Middle Fork flows through an isolated, roadless canyon.[22] Almost 78 miles (126 km) of the Middle Fork are designated a National Wild and Scenic River.[30] The river enters Butte County shortly before flowing into Lake Oroville; the New Bidwell Bar Bridge crosses the lake's Middle Fork arm near its confluence with the North Fork arm.[31] The Middle Fork's tributary, the Fall River, forms Feather Falls, which at 410 feet (120 m) is one of the largest waterfalls in northern California.[32]

The Middle Fork is 96 miles (154 km) long, or 129 miles (208 km) including the Sierra Valley Channels and Little Last Chance Creek.[7] It drains an area of 1,365 square miles (3,540 km2).[7] The average discharge near the mouth, for the period 1951–1986, was 1,489 cubic feet per second (42.2 m3/s).[33]

South Fork[edit]

The South Fork flows south of, and parallel to the lower half of the Middle Fork. It begins just upstream of Little Grass Valley Reservoir, in southeastern Plumas County.[34] Below the reservoir it flows southwest through a canyon and empties into Lake Oroville near Forbestown.[35] Along its course, the South Fork is dammed several more times for hydropower generation. The South Fork arm of the lake joins the Middle Fork just upstream of the Bidwell Bar bridge. The South Fork is 44.3 miles (71.3 km) long; it drains the smallest area of all the forks at 157 square miles (410 km2).[7] The average discharge of the South Fork between 1911 and 1966 was 305 cubic feet per second (8.6 m3/s).[36]

Main stem[edit]

The Feather River proper begins in Butte County at the base of Oroville Dam, which at 770 feet (230 m) is the tallest dam in the United States. Lake Oroville is the second largest artificial lake in California with a capacity of 3.5 million acre feet (4.36 billion m3), and greatly moderates seasonal flows in the lower Feather River.[citation needed] Immediately below Oroville Dam is the Thermalito Diversion Dam and a group of hydroelectric facilities collectively called the Oroville-Thermalito Complex, all adjacent to the city of Oroville.[37] Downstream of Oroville the Feather River turns south; west of Palermo it flows through the Oroville Wildlife Area which preserves a section of native riparian woodland habitat.[38][39]

The Feather River continues south through farmland, where Gridley and Live Oak are to the west of the river.[40] Near Live Oak, the river forms the Butte–Sutter County line for a brief stretch before the confluence with Honcut Creek from which it begins to form the boundary of Sutter County (west) and Yuba County (east).[41] The river then flows between Yuba City, county seat of Sutter County and Marysville, county seat of Yuba County, which together form the largest urban area in the Feather River basin.[15]: 142 Here, it is joined from the east by the Yuba River, its biggest tributary below Oroville Dam.[42]

South of Yuba City–Marysville, the Feather River flows past the communities including Olivehurst and Plumas Lake, and receives the Bear River from the east near Rio Oso.[43][44] Below there, the Feather River flows entirely within Sutter County. It passes Nicolaus and is joined from the northwest by the Sutter Bypass, an artificial channel that drains floodwaters from the Sutter Basin lowland between the Sacramento and Feather Rivers, as well as floodwaters diverted from the Sacramento River and Butte Creek.[44][45] Between the confluences of Yuba River and Sutter Bypass, the six units of the Feather River Wildlife Area are scattered along the Feather River.[46] The Feather River empties into the Sacramento River at the unincorporated community of Verona, about 5 miles (8.0 km) east of Knights Landing in southern Sutter County.[47][48]

Unlike its fast-flowing tributaries in the Sierra Nevada, the lower Feather River is a wide meandering stream. The river channel is naturally prone to avulsion (course changes) due to the flat terrain and frequent flooding. The floodplain has been constrained by man-made levees since the late 19th century; levee spacing on the lower river ranges from 0.5 to 2.7 miles (0.80 to 4.35 km) apart.[49]: 62–64 The Feather River valley forms the corridor for Highway 99, which parallels the west side of the river from Oroville until Nicolaus (below the Bear River confluence) where it crosses to the east side, and SR 70 which parallels the east side of the river from Oroville to where it joins Highway 99 south of Nicolaus.[22] The Union Pacific Railroad (UP)'s Sacramento Subdivision tracks parallel the east side of the river between its mouth and Yuba City-Marysville. The Feather River Route continues along the east side of the river from there north to Oroville, while the UP Valley Subdivision continues on the west side of the river on its way north towards Dunsmuir.[citation needed]

Natural history[edit]

Geology[edit]

The upper Feather River basin occupies a unique geological setting at the juncture of the Sierra Nevada and the Cascade Range. Most of the upper Feather basin is geologically part of the Sierra Nevada, which consists mostly of granitic plutons (77–225 million years of age) intruding into older marine metamorphic rocks. In the North Fork drainage, much younger Cascade volcanic rock (mostly basalt less than 6 million years of age) overlie the Sierran rocks; this contact is exposed at several locations along the North Fork canyon including near Belden.[50] The Diamond Mountains, in the eastern portion of the basin, are a series of northwesterly-tilted fault blocks geologically similar to ranges of the Basin and Range Province further east. They are separated from the main crest of the Sierra by the Plumas Trench, a graben formation extending northwest from the Sierra Valley to the American Valley.[13]: 5

The lower Feather River flows through the Great Valley geologic province, a gently sloping terrain dominated by alluvial deposits. Alluvium can bes extremely deep with deposits up to 66 million years of age.[51]: G7 On the Feather, Yuba and Sacramento rivers, repeated flooding over millennia deposited sediment along the river banks, creating natural levees that slope gently away from the river channels, and consequently a natural pattern of inter-riverine flood basins that – in their natural state – were described by geologist Kirk Bryan in the 1920s as "swampy and frequently submerged wastes".[52] : 10 Along the border of the Sierra foothills, tectonic uplift has elevated older alluvial deposits, which have since been subjected to erosion, producing an irregular undulating landscape.[51]: 9

The Sierra foothills form the boundary between the Sierra Nevada and Great Valley provinces and are seismically active. The foothill area between Oroville and Folsom comprise the Foothills Fault System, which includes the Melones and Bear Mountain fault zones.[53]: 4 In 1975, the magnitude 5.7 Oroville earthquake occurred on this system; some suggest the quake was caused by the weight of the reservoir behind Oroville Dam, which had recently filled for the first time.

The Feather River basin contains sediments from a number of ancient Tertiary river beds, which were elevated with the uplift of the Sierra Nevada and now sit hundreds of feet above the present-day river channels. Much of the gold that would be found during the California Gold Rush originated from these sediments; over millions of years gold flakes were exposed by erosion and washed into active river channels, where they accumulated as placer gold. What is known as the ancient "Jura River" flowed roughly along the course of the upper Middle Fork and East Branch, then turned north. Ancient river beds are also exposed along the Yuba and Bear rivers further south. The southern sediments were much richer in gold and as a result were heavily exploited by hydraulic mining in the 1850s, washing billions of tons of sediments into river channels.

Hydrology and climate[edit]

The Feather River derives the vast majority of its water flow from the Sierra Nevada and Cascades, which correspond to two major hydrologic regions. The major southern tributaries – the Middle Fork, Yuba and Bear rivers – drain large areas of exposed granite and thin rocky soils. Water infiltration is low, and stream flows respond directly to rain and snowmelt, with the highest flows in winter and spring.[54]: 16 Rock in the Cascade Range portion, particularly north of Lake Almanor, is far more porous with the consequence of much greater groundwater percolation and storage. Due to this, the North Fork has a strong and consistent flow in the dry summer months when the other tributaries of the Feather River are at their lowest.[12]: 9

Due to its location near the northern end of the Sierra, the Feather River basin is lower in elevation than other major Sierra rivers, with large areas close to average snowline but not extending high above it. On average, precipitation volume is evenly split between rain and snow, though this can vary widely year to year.[55] Because of this, there are two major periods of high flow in winter (rain) and spring (snowmelt), and there is a high risk of rain-on-snow flooding as well.[12]: 1 The Feather River basin has been particularly vulnerable to warming temperatures in recent decades, as snowline has gradually shifted up in elevation and peak snowmelt shifts earlier in the year. Between 1949 and 2010, the East Branch has seen a 27 percent decrease in April-June runoff, but a 39 percent increase in March runoff.[54]: 17

Water flow in the lower Feather River has been heavily affected by damming; the Feather, Yuba and Bear rivers are all controlled by multiple reservoirs which are primarily operated for summer irrigation. The spring snowmelt peak (April-June) has been largely eliminated, with higher volumes of water distributed over the late summer and fall when natural flows would have been at their lowest. Winter (December-March) rain flood peaks have also been mostly eliminated due to operation of reservoirs for flood control. However, monthly flow volumes have either remained the same or increased, because stormwaters are eventually released to maintain flood control space in the reservoirs.

Monthly discharge at Nicolaus, 1942–1967[56]

| Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Monthly discharge at Nicolaus, 1968-1983[57]

| Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Ecology[edit]

Plants and wildlife[edit]

About 70 percent of the upper Feather River basin is coniferous forest, mixed with smaller areas of grasslands and alpine meadows.[10]: 136 The Plumas National Forest covers the majority of this area. Higher elevations, above about 6,000 feet (1,800 m) elevation, are dominated by Abies magnifica (red fir) and Pinus contorta (lodgepole pine) at the highest elevations. From there down to about 1,500 feet (460 m) elevation, forests are a mix of pine, fir and cedar, with Pinus ponderosa (ponderosa pine), Pseudotsuga menziesii (Douglas-fir) and Abies concolor (white fir) the most prevalent species. Oak woodland dominates the foothills at elevations below 1,500 feet (460 m); between 1,500 to 2,000 feet (460 to 610 m), there is a mix of conifers and broadleaf trees.[58] There are areas of Quercus douglasii (blue oak) woodland and also Quercus kelloggi (black oak) scattered throughout the canyons. There are also large areas of chaparral in and just above the foothill zone. Sagebrush is prevalent on drier slopes east of the Sierra crest, including in the Diamond Mountains.[10]: 136

Although most streams in the upper basin are rocky and fast-flowing, a number of valleys support significant riparian and wetland habitat.[10]: 136 The 120,000-acre (49,000 ha) Sierra Valley contains the largest wetland in the upper Feather River system. The valley is fed by numerous mountain streams which converge in a wetland complex known as the Sierra Valley Channels, providing an important regional habitat for migratory birds. The lower Feather River basin formerly had extensive wetlands, but has been almost entirely converted for agriculture. The river and its floodplain have been significantly altered from their historic state by levee construction and hydraulic mining debris. However, the river still provides significant riparian habitat. Dense riparian forest is still found in a few areas and includes Quercus lobata (valley oak), Populus fremontii (Fremont cottonwood), Acer negundo (box elder), Fraxinus latifolia (Oregon ash), and several willow species including Salix laevigata (red willow). More open forest areas include Juglans hindsii( black walnut), and Platanus racemosa (western sycamore). Other parts of the river corridor include perennial and seasonal wetlands and riparian scrub in the flood zone, and upland scrub and grassland communities on higher ground.[59]

Fish[edit]

The Feather River was historically home to large spawning populations of fall and spring-run chinook salmon and king salmon, and fall-run steelhead trout. Spawning grounds were located along 30 miles (48 km) of the Feather River below Oroville, and along many of the forks of the Feather River above Oroville. Salmon migrated up all the forks of the Feather River, with the furthest runs as far as the North Fork headwaters near Lassen Peak. They also migrated all the way to the headwaters of the West Fork. The East Branch, Middle Fork and South Fork all contained natural barriers that prevented salmon from swimming very far upstream. On the East Branch this was near the confluence of Indian and Spanish Creeks; on the Middle Fork it was at Bald Rock Falls (near Feather Falls) and on the South Fork this was near Forbestown.[60][61] Due to variation in water levels, the spring run extended further upstream than the fall run, although the fall run was larger due to fall being the peak spawning season. Little is known about the historic range of steelhead but it is assumed they could reach the same areas that salmon did, or even further upstream because they favor smaller tributaries to spawn.

Salmon and steelhead began declining during the Gold Rush, when hydraulic mining (and placer mining, to a lesser degree) generated large volumes of sediment that greatly altered the river channels. In 1871 the California Fish Commission reported that salmon had ceased to visit the Feather, Yuba and American Rivers in some years.[62] Populations struggled to recover in the 20th century due to commercial fishing and water diversions for agriculture. The construction of Oroville Dam in 1968 totally blocked salmon and steelhead from reaching the upper Feather basin. The Yuba and Bear Rivers were also dammed, with no provisions made for fish passage. The Feather River below Oroville has no dams, but most of the historic spawning habitat is gone due to levee construction, mining sediments, and the elimination of spring flooding by Oroville Dam. There are no reliable estimates of the size of salmon and steelhead runs prior to the 20th century.

After the construction of Oroville Dam, the Feather River Fish Hatchery was built to compensate for the loss of suitable spawning habitat above the dam. This had the effect of increasing salmon and steelhead populations somewhat from their historic low during the 1950s, when the fall run for salmon averaged 39,000 and the spring run 1,700.[63] By the 1990s, the fall run averaged 51,400 fish and the spring run averaged 3,800. The hatchery also supports about 1,000 returning fall run steelhead. About 99 percent of salmon and steelhead in the Feather River are now of hatchery stock. Natural spawning is limited to a very short stretch of the Feather River at Oroville.[64]

History[edit]

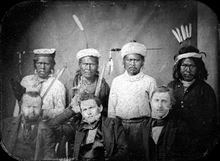

Indigenous peoples[edit]

The Feather River basin was originally inhabited by the Maidu people, whose ancestors first arrived in the area around 3,500 years ago. Because Maiduan languages have no written form, there is no record of their history prior to European contact. The three major groups of Maidu were all present in the Feather River area. The Yamani (Mountain Maidu) inhabited the upper basin across most of present-day Plumas County, primarily along the North Fork, East Branch, and Middle Fork. The Konkow lived in the foothills and valley near present-day Oroville, ranging out into the Sacramento Valley as well as up the West Branch and South Forks of the Feather River. The Nisenan (Southern Maidu) were along the lower Feather River, and the Yuba and Bear Rivers.

In the upper basin, permanent villages were located within the numerous lower valleys along the North Fork and East Branch, primarily in Indian, Genesee and American Valleys. Villages were located along the edges of valleys and were typically small, with less than 100 people. The villages were composed of cedar bark houses (K'um). Most settlements were independent clans, with no larger tribal organization. Due to the rugged terrain, trade or interaction between villages outside of their home valleys was infrequent. Higher elevation valleys, including Big Meadows (now Lake Almanor), Mohawk Valley, and Sierra Valley were used as hunting grounds in summer, where wigwams were built as temporary dwellings. Few if any permanent settlements were situated here due to the heavy snowfall in winter.[65]

On the lower Feather River, the center of the Nisenan population was around the confluence of the Feather and Yuba rivers, near what is now Marysville. The Valley Nisenan, as the people of this region are known, lived in larger communities of up to 500 people, sited on mounds to avoid the river's annual flooding. Houses were generally built of earth or tule, which was once abundant in the expansive wetlands along the river. These were some of the largest settlements in pre-colonial North America that did not practice agriculture. The abundance of food plants and waterfowl, fish and game allowed a hunter-gatherer lifestyle year round. The Feather and Sacramento Rivers also provided trade routes between the Nisenan and groups along the Pacific Coast.[66]

Historically, the huge salmon and steelhead runs of the Feather River were a primary food source during certain times of the year:

"The Feather River was partially closed by piles extending nearly to the middle of the stream. These piles were interwoven with brush so as to prevent the passage of the fish. They were thus compelled to pass through the opening, where the Indians on platforms, captured them with their spears in their ascent of the stream."[63]

Several other tribes also used the Feather River area. The Northern Paiute and Washoe had their territory further east in the Great Basin, including around the Honey Lake area, but in summer they would visit the Feather River basin to hunt. The Yana territory bordered Maidu land in the Sierra foothills, around present-day Oroville. The Yana and Maidu were known to be enemies, and this area was disputed between them. The Atsugewi lived in the Cascades north of the Feather River basin, with their lands extending down to approximately the Lassen Peak area. Although the Wintu lived much further north (around Mount Shasta), they often traveled here to trade with the Maidu.

Beginning of European colonization[edit]

Although the Spanish began to colonize California in the 1760s, there are no known explorations as far north as the Feather River. After California became part of Mexico in 1822, fur trappers began to explore the Feather River watershed, which was then abundant in beaver. Jedediah Smith explored the area north from present-day Sacramento in 1828, reaching the Feather River around March 11; he and his party trapped beaver up the river as far as Sutter Buttes. However they did not explore further upstream on the Feather, instead heading north towards what is now Red Bluff.[67] Smith noted one of the indigenous names for the river as "Ya-loo". (Gudde and Bright) Peter Skene Ogden and Roderick McLeod, both of the Hudson's Bay Company, may have crossed the Sierra Nevada via the Feather River, which would make them the first non-Native Americans to cross by this route. However, they probably traveled via an easier route along the Pit River further north.[68]

The origin of the river's name is somewhat ambiguous, although derived from the Spanish "El Rio de las Plumas" (The river of feathers), there is "no conclusive evidence" that the Spanish actually used the name during the colonial period. The first recorded use of the "Plumas" name was during an 1836 expedition by John Marsh and Jose Noriega, who noted large piles of feathers along the banks of the river and that the Native Americans of the area wore clothing richly decorated with feathers. Maps and documents from the 1830s onward generally refer to the river by its modern name, although as late as 1852 some maps still used the name "Plumas".[69]

In 1841 the Mexican government granted John Sutter a large tract of land in the Sacramento Valley, which he named New Helvetia. This initially extended from Sacramento north to about five leagues above the confluence of the Feather and Yuba Rivers. In 1842 Theodore Cordua leased the part of Sutter's land north of the Yuba River and requested Mexico grant him another ten leagues along the Feather River upstream of there, establishing a colony of his own called New Mecklenburg. In 1844 he was granted Rancho Honcut, with its 31,000 acres (13,000 ha) bounded by the Feather River, Yuba River and Honcut Creek. By 1847 Cordua had thousands of cattle, hog and chickens, and farmed wheat, barley and peas on the rich soils surrounding the Feather River. The operations of the ranch depended almost entirely on Native American labor. However, the market for these products was small. Starting in 1848 the California Gold Rush brought a huge influx of immigrants to California, but the gold fever also left Cordua, Sutter and other major landholders short on labor, and soon bankrupted them. Cordua left California in 1852, never to return.

Gold Rush[edit]

Prospectors came to the Feather River not long after the initial gold discovery on the American River in 1848. After receiving word of the discovery, John Bidwell led a party of about 50 Native Americans and seven white men to search for gold in the Feather River. They reportedly extracted $70,000 of gold in seven weeks.[70] That area became known as Bidwell (or Bidwell's) Bar and by 1856-57 had grown into a mining camp of more than 2,000 people. It served briefly (when?) as the county seat of Butte County. In 1855 the Bidwell Bar Bridge, the first suspension bridge west of the Mississippi River, was constructed here. It remained in use until the 1950s when it was relocated due to the construction of Oroville Dam. The original town site is now inundated under Lake Oroville.[71] Bidwell later used the profits from his mining operation to purchase Rancho Arroyo Chico, where he eventually founded the city of Chico.

In 1850 Thomas Stoddard, carrying a sack full of gold nuggets, walked into a mining camp on a tributary of the Feather River. He claimed to have discovered a lake somewhere in the upper Feather with much gold along its shores. When Stoddard proposed an expedition to find "Gold Lake", as many as a thousand men joined. After a long, unsuccessful search, threatened to hang Stoddard, but he escaped. What is now known as Gold Lake near present-day Graeagle was named by the miners in reference to the myth. The rumor quickly spread and soon thousands more prospectors were headed to the Feather River. The alleged lake was never found, but nevertheless large amounts of gold were found along the river and its tributaries. Numerous mining camps were established, some of which grew into towns, including Quincy and Crescent Mills. Other rich mining areas included the Union Cape claim along the North Fork above Oroville, where the entire river was diverted into a mile-long flume so the bed could be prospected. The Nelson Point camp along the Middle Fork, near what is now the Nelson Creek tributary, became the gateway to numerous mining sites along the Middle Fork that produced more than $20 million worth of gold. Another particularly productive area was the Forbestown District, located along the South Fork.[72] The Yuba and Bear River tributaries were also home to particularly rich gold-bearing deposits.

Marysville (originally Yubaville) was created after Theodore Cordua's land holdings were acquired by four entrepreneurs, who in 1850 commissioned a master plan for a town located at Cordua's original homestead. The town was incorporated in 1851. It grew rapidly due to its strategic location at the junction of the Feather and Yuba Rivers, which then carried steamboats from Sacramento transporting miners and goods into the area. By 1853 Marysville had a population of 10,000 and was the third largest city in California, after San Francisco and Sacramento. Oroville was established around 1852(?) and served as a gateway to the upper Feather River basin. After disembarking from riverboats, miners traveled on foot or horseback into the various drainages of the Feather River forks.

Starting in the late 1850s and 1860s hydraulic mining was heavily used in the Yuba and Bear River watersheds, and to a lesser extent in the upper Feather watershed. Malakoff Diggins, located near Nevada City, was the largest hydraulic mining site in California, leaving a scar on the landscape 7,000 feet (2,100 m) long, 3,000 feet (910 m) wide and over 600 feet (180 m) deep. The result was a large influx of sediment to the lower Feather River. This reduced the depth of the stream bed and blocked steamboats from reaching Marysville (although by this point railroads had largely replaced steamboats as the primary transportation link to Sacramento). Mining debris also increased the severity of flooding, with catastrophic events in 1862 and 1868(?) inundating Marysville. Mining sediments also destroyed or damaged over 50,000 acres (20,000 ha) of farmland adjacent to the Feather, Yuba and Bear Rivers.[62]

Beckwourth Trail[edit]

James "Jim" Beckwourth came to California around 1848, and soon began exploring the northern Sierra Nevada. In spring 1850 Beckwourth discovered what is now known as Beckwourth Pass at the east end of Sierra Valley. As the lowest mountain pass in the Sierra Nevada, this soon became heavily used by California-bound settlers seeking an alternative to the Donner Pass on the California Trail west of Reno. Beckwourth led the first wagon train over the pass in 1851.

The Beckwourth Trail, formed by joining several existing Native American trails, traveled west through Grizzly Valley (where Lake Davis is now located) before crossing over to the Middle Fork in the vicinity of present day Spring Garden, then continuing north through the American Valley near present day Quincy. From there it went southwest through the mountains avoiding the rugged North and Middle Fork canyons (approximately along the present-day route of Oroville-Quincy Highway), reaching the foothills at Oroville. The trail then continued south along the Feather River to Marysville. It was used heavily during the Gold Rush years until about 1855, and was largely disused after the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad in 1869. After the Gold Rush Beckwourth began ranching in the Sierra Valley, giving his name to the present-day town of Beckwourth.

Removal of Native Americans[edit]

The influx of miners into the Feather River country displaced Native Americans in the upper basin, where villages often occupied prime locations for gold mining. Although native peoples were initially friendly, they soon became embroiled in land conflicts with the settlers, who either killed them or drove them off their land. Others were enslaved to mine gold, where the harsh working conditions led to further deaths. Survivors were forced to retreat further into the mountains, often to poor locations with little food or water. Later, as ranchers began to move into the upper Feather River basin, they were often raided by starving Native Americans, leading to bounties being placed for their scalps. Around 1865, a group from the nearby Yahi (originally from around present-day Chico) went into hiding in the mountains above Oroville. The last survivor of this group, Ishi, was captured while hunting near Oroville in 1911. He later gained fame as the "last wild Indian in California" and became the subject of an effort by anthropologists to reconstruct Yahi culture.

Along the lower Feather River, indigenous populations had been decimated by malaria and cholera epidemics in the 1830s and 1840s, likely introduced by fur trappers. By the mid-1850s the population had fallen to a few hundred, from several thousand prior to the arrival of Europeans. Due to the continuing conflicts between Native Americans and settlers, the U.S. government attempted to negotiate a treaty at Bidwell's ranch in 1851, which would have established a reservation in the area between Oroville, Chico and Nimshew (where?). However, not all the chiefs present agreed to sign the treaty, as their people did not wish to leave their original lands. The treaty was then rejected in Congress because the proposed reservation occupied prime agricultural land. In 1859 the governor of California appointed General Kibbe (?) to lead an expedition to round up all the remaining Native Americans along the north fork of the Feather River, primarily of the Konkow Maidu. They were forcibly marched to the Mendocino Indian Reservation, then later to the Round Valley Indian Reservation. Over the following winters, many died due to a lack of food and supplies.[73] Some of their descendants still live on this reservation today.

Feather River Route[edit]

After the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad over Donner Pass in 1869, there was interest in creating a second route over the Sierra Nevada. A railroad along the Feather River was first envisioned by Arthur Keddie, who sought to compete with the Southern Pacific Railroad that owned the Donner Pass line. It was not until 1902 when Keddie partnered with George Jay Gould, who owned the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad, to form the Western Pacific Railway (WP, later Western Pacific Railroad), which would build a line from Oroville to Salt Lake City via Beckwourth Pass. Construction began on the western end on January 1, 1906. When completed in 1910, it was one of the most expensive railroads ever built at the time, with a total cost approaching $60 million. The "Inside Gateway" line, connecting the WP to the Great Northern Railway with a junction at Keddie, was opened in 1931. It features the Keddie Wye, which spans Spanish Creek, a tributary of the East Branch Feather River.[74]

The WP offered much gentler grades than Southern Pacific (1% compared with up to 3% over Donner Pass), allowing trains to run at lower cost, but has a longer total distance. It suffered financial troubles for much of its existence, in part due to the unstable geology of the North Fork Feather River canyon, where landslides frequently shut down the line. The California Zephyr passenger train ran on this route from 1949 until its discontinuation in 1970; after Amtrak revived the service in 1971 it would run over Donner Pass instead. In 1982 the entire WP, including the Feather River Route, was purchased by the Union Pacific Railroad, which continues to operate the line today. Flooding of the Feather River in 1997 damaged or destroyed almost 100 miles (160 km) of the route, which cost $30 million to repair.

Controlling floods[edit]

After the disastrous flooding events of the 1860s, communities, landowners and water districts along the Feather River engaged in building ever higher levees. In particular, Marysville encircled itself with high levees that ended up preventing further outward growth of the city. Although hydraulic mining was banned in 1884, mining sediment continued washing down from the mountains for many years afterward, filling the channels of the Feather and Yuba Rivers and causing them to continually break through the levees. Starting in the early 1900s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers intervened, carrying out large scale dredging of the Feather and lower Sacramento rivers, hoping to restore navigation to the latter river. By 1920 the Feather River bed had largely returned to its original elevation, both due to dredging and natural erosive forces as the volume of mining sediment finally began to decrease. It was not until 1950 when the Yuba River was restored to its original elevation, due to the greater impacts of mining there.[citation needed]

Major floods in the Sacramento Valley during 1907 and 1909 were the impetus for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to construct the Sacramento River Flood Control Project, which consolidated 980 miles (1,580 km) of independent levee systems along the Sacramento, Feather and American Rivers and created large flood bypasses. The project greatly altered the hydrology of the Feather River. In order to protect the lands between the Feather and Sacramento Rivers from flooding, a large flood basin (Butte Basin) was created northwest of Sutter Buttes. During periods of high water on the Sacramento River, water enters the basin via several weirs. The Sutter Bypass drains water from the Butte Basin and Butte Creek (which formerly flowed directly into the Sacramento River) southeast into the Feather River, whose channel below Nicolaus(?) was enlarged to accommodate floodwater from the Sacramento River. On the opposite bank of the Sacramento River from where the Feather River flows into it, the Fremont Weir was constructed, to drain the combined floodwaters from both rivers into the Yolo Bypass, which protects the city of Sacramento from flooding.

After many decades of work, the system was completed in 1957. Flood protection along the Feather River was further improved eleven years later after the construction of Oroville Dam. The dam held back the Christmas flood of 1964 even though it was still under construction at the time; it also prevented major flooding in 1986. Oroville Dam provides 750,000 acre-feet (930,000,000 m3) of flood control storage; New Bullards Bar Dam, completed on the Yuba River in 1969, provides another 170,000 acre-feet (210,000,000 m3). During the floods of 1997, an atmospheric river storm stalled for several days over the upper Feather River basin, resulting in a peak flow of 300,000 cubic feet per second (8,500 m3/s) into Lake Oroville. These were the highest flows ever recorded on the Feather River; though the 1862 flood was likely larger, no official flow records exist for that time. Levees broke along the Feather River and Sutter Bypass, flooding thousands of acres of farmland in the Sutter Basin, but overall the system worked as intended, protecting Marysville, Yuba City and Sacramento.[75]

During the 2017 California floods, the Feather River reached its highest peak since 1997 at almost 200,000 cubic feet per second (5,700 m3/s). The concrete lining of the Oroville Dam main spillway failed due to cavitation from the force of high water flows. The main spillway was temporarily shut down, and water was allowed to flow over the never-before-used emergency spillway, which also nearly failed. The threat of flooding led to a major crisis during which 188,000 people along the lower Feather River were evacuated. However, inflows subsided before too much damage could occur and the structural integrity of the dam was not compromised. The spillways were repaired by 2019 at a cost of $500 million.

State Water Project[edit]

In 1956 the California Department of Water Resources was formed to build a statewide water management system, with the primary goal of conveying water from Northern California to the drier south, particularly Los Angeles. State Engineer A.D. Edmonston had proposed a dam on the Feather River and a aqueduct system to the south as early as 1951, but it was not until 1955 when the project began to rapidly move forward. In December, severe flooding struck northern California (two years before the Sacramento River flood control system was complete). The Feather River burst its banks, flooding Yuba City and killing 37 people. In the wake of the flood, local officials called for the construction of a dam on the Feather River. The federal Flood Control Act of 1958 authorized emergency funding to begin construction on the dam, and soon afterwards the state of California took over the project.[76][77] (MDPI: Risk and Resilience at Oroville Dam)

Although local residents welcomed the flood protection the dam would bring, overall Northern California voters opposed what they saw as a water grab by Los Angeles. The bonds necessary to fund the State Water Project passed by a slim margin in 1959, carried almost entirely by voters in Southern California. Although the project was intended for urban water supply, among the most adamant lobbyists for the project were farming corporations and irrigation districts in the San Joaquin Valley, through which an aqueduct would run before reaching Los Angeles. As a direct result of this, agricultural interests secured a significant portion of Feather River water.[78] About 30 percent of state water is used in the San Joaquin Valley, most of that in Kern County.[79] On average, the State Water Project delivers 2,400,000 acre-feet (3.0×109 m3) per year, or about 40 percent of the flow of the Feather River.

In addition to Oroville Dam, completed in 1968, the State Water Project built three other dams in the upper Feather River watershed, forming Antelope Lake, Lake Davis and Frenchman Lake. However, their capacity is small relative to the size of Oroville. Several dams were also built for the Oroville-Thermalito Hydroelectric Complex downstream of Oroville. Although the first water deliveries were made in 1962 (to the San Joaquin Valley), water was not delivered to Los Angeles until 1973. The filling of Lake Oroville necessitated the relocation of the Western Pacific Railroad and State Route 70, which were rebuilt to the west on new alignments. In addition a new suspension bridge was constructed at Bidwell's Bar for State Route 162 (Oroville-Quincy Highway). In the years before the dam was filled, the new Bidwell's Bar bridge was the third highest bridge in the world, with its deck 627 feet (191 m) above the Middle Fork. The deck now sits about 50 feet (15 m) above the water when the reservoir is full.

Modern uses and issues[edit]

Hydroelectricity[edit]

Starting in the late 19th century, a number of hydroelectric projects were built in the upper Feather River basin, which today is one of the largest hydropower producing regions in California. The first major hydroelectric project along the Feather River was the Big Bend Powerhouse along the North Fork, completed in 1908 by the Great Western Power Company. At its completion, it featured the largest individual turbines, transformers and penstocks in the world, and was the largest hydroelectric project in the western United States.[80] In 1910, the North Fork was dammed at Big Meadows to create Lake Almanor, helping to regulate the water flow through Big Bend. Lake Almanor also provides water to the Butt Valley and Caribou I powerhouses via a diversion through Butt Valley Reservoir, constructed in 1924. This scheme is known as the Upper North Fork Feather River Project.[81] (In the 1960s, Big Bend Powerhouse would be inundated by the filling of Lake Oroville.)

In 1928, Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) constructed the Bucks Creek Project, which today is operated by PG&E and the City of Santa Clara. The project is located on Bucks Creek, a tributary of the North Fork, and includes Bucks Lake and two powerhouses. It generates an average of 48,900 megawatt hours annually. The Bucks Creek Powerhouse has a hydraulic head of 2,558 feet (780 m), the highest of any plant owned by PG&E.[82] In 1930, PG&E acquired Great Western and with it the Upper North Fork Project. Between 1930 and 1970 it constructed three more powerhouses for the Upper North Fork Project (Caribou II, Oak Flat and Belden) and three more powerhouses on the North Fork between the East Branch confluence and Big Bend (Rock Creek, Cresta, and Poe).

The South Feather Power Project was constructed in the 1950s and 1960s by the South Feather Water and Power Agency. It consists of four powerhouses on the South Fork Feather River and a number of storage reservoirs, including Little Grass Valley Reservoir and Sly Creek Reservoir. As of 2007, the South Feather Project generated an average of 514,100 megawatt hours annually.[83] The smaller DeSabla-Centerville Project, with three reservoirs and two powerhouses, is located on the West Branch Feather River and Butte Creek. It was originally built in ??? By ????, and was acquired by PG&E in ????.[84]

In 1953, PG&E and developer Robert P. Wilson both filed with the Federal Power Commission to construct a hydroelectric system on the Middle Fork. Both plans would have involved constructing at least five dams on the Middle Fork, and several more on tributaries, including the Fall River, where power would be generated using the drop at Feather Falls. The Richvale Irrigation District, which also sought to use water from the river, petitioned against these projects, and was ultimately granted a preliminary permit to develop the river. The irrigation district's plans were canceled when the Middle Fork was designated a National Wild and Scenic River in 1968, preventing any future damming of the river.[85][86]

The Oroville Dam and Oroville-Thermalito Complex, built in the 1960s as part of the State Water Project, include a number of large hydroelectric stations. The 819 megawatt Edward Hyatt Power Plant is located at the base of Oroville Dam, and is a pump-generating plant that pumps water back up into Lake Oroville during periods of low power demand. The Feather River is also diverted below Oroville Dam into the Thermalito Forebay and Thermalito Afterbay, which serve as the upper and lower reservoirs for the 114 megawatt Thermalito Pumping-Generating Plant. These plants are designed to produce peaking power, the sale of which helps cover the cost of operating the State Water Project.[87]

Water supply[edit]

The Feather River has provided water for agriculture since the Gold Rush, when the first ditches were dug to divert water from small tributaries. Agriculture along the Feather River was initially served by numerous small private ditch companies. In 1903 the Butte County Canal Company was organized, in order to construct an irrigation system for the lands south of Chico between the Feather River and Sacramento River. They raised funds by selling water rights to local farmers and ranchers, who in total held some 15,000 acres (6,100 ha). In 1904 construction began on the Cherokee Canal, which diverted water directly from the Feather River near Oroville. Initially, this system mainly watered land in the area of Biggs and Gridley, where the soils were most suitable for agriculture. The primary crops were alfalfa, peaches, beans and grapes, all of which are still grown here today.

In 1911 the system was acquired by the Sutter-Butte Canal Company, which had an interest in expanding the agriculture business. However, the lands further north and west consist of heavy clay soils that were unsuitable for most crops then grown in California. They successfully experimented with growing rice, which within a few years became one of the largest crops in the area. The irrigated area was tripled, and a large tract west of Oroville called Richvale Colonies was subdivided for the express purpose of rice cultivation.[88] Due to the scale of its operation and its water rights dating from 1903-1905 (among the oldest non-mining water rights on the Feather River), Sutter-Butte held a near monopoly on Feather River irrigation water until the 1950s. It was the primary water source for local agricultural and municipal water districts including the Richvale Irrigation District established in ?, Biggs-West Gridley Water District (1942),[89] Butte Water District (1952),[90] and Sutter Extension Water District in ?. In 1942 the Biggs-West Gridley district purchased about a quarter of Sutter-Butte's distribution system and water rights; in 1957 the remainder of Sutter-Butte was liquidated and subsequently acquired by the four water districts.

During the planning stages of the State Water Project in the 1950s, it became clear that the proposed development of the Feather River would have major implications for water supply in the local area. In 1957 the four districts formed a Joint Water Districts Board to manage their shared water supply, and in 1969 they entered an agreement with the State of California for 555,000 acre-feet (685,000,000 m3) per year from the State Water Project. Ultimately, the Cherokee Canal was modified to draw its water from Thermalito Afterbay rather than its original intake on the Feather River.

Recreation and tourism[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "North Fork Feather River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1981-01-19. Retrieved 2010-10-23.

- ^ "Rice Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1990-08-01. Retrieved 2010-10-23.

- ^ "Middle Fork Feather River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1981-01-19. Retrieved 2010-10-23.

- ^ "Sierra Valley Channels". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1981-01-19. Retrieved 2010-10-23.

- ^ "Lake Oroville". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1981-01-19. Retrieved 2010-10-23.

- ^ a b "Feather River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1981-01-19. Retrieved 2010-10-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "National Hydrography Dataset via National Map Viewer". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2017-09-24.

- ^ a b c d "Boundary Descriptions and Names of Regions, Subregions, Accounting Units and Cataloging Units". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "USGS Gage #11425000 Feather River near Nicolaus, CA: Monthly Statistics". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1944–1983. Retrieved 2018-11-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Upper Feather River Watershed" (pdf). Sacramento River Watershed Program. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ "California Central Valley Unimpaired Flow Data" (PDF). California Department of Water Resources. May 2007. Retrieved 2017-09-24.

- ^ a b c Koczot, Kathryn M.; et al. (2005). "Precipitation-Runoff Processes in the Feather River Basin, Northeastern California, with Prospects for Streamflow Predictability, Water Years 1971–97" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b c d Ecosystem Sciences (2004-05-14). "Feather River Watershed Management Strategy" (PDF). California Department of Water Resources. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ a b George, Holly; et al. (Mar 2007). "Upper Feather River Watershed (UFRW) Irrigation Discharge Management Program". University of California, Division of Agriculture and National Resources.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b c "Lower Feather River Watershed" (pdf). Sacramento River Watershed Program. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ "Yuba River Watershed" (pdf). Sacramento River Watershed Program. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ "Bear River Watershed" (pdf). Sacramento River Watershed Program. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Childs Meadows, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Chester, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- ^ "PG&E's Hydroelectric Stairway of Power". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2018-11-06.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Storrie, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g California Road and Recreation Atlas (Map) (10 ed.). Cartography by Allen, Neil et al. Benchmark Maps. 2017. pp. 53–54, 59–61, 64.

- ^ "USGS Gage #11404900 Combined flow North Fork Feather River at Pulga + Poe Powerplant, CA: Monthly Statistics". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1967–1983. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ "USGS Gage #11403000 East Branch of North Fork Feather River near Rich Bar, CA: Monthly Statistics". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1950–1983. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Jonesville, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Paradise East, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Cherokee, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ "USGS Gage #11403000 West Branch Feather River near Yankee Hill, CA: Monthly Statistics". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1930–1963. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Portola, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ "Feather River (Middle Fork), California". National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Oroville Dam, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ "Feather Falls". World Waterfall Database. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ "USGS Gage #11394500 Middle Fork Feather River near Merrimac, CA". National Water Information System. 1951–1986. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

{{cite web}}: Text "U.S. Geological Survey" ignored (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: La Porte, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Forbestown, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ "USGS Gage #11397000 Middle Fork Feather River near Merrimac, CA". National Water Information System. 1911–1966. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

{{cite web}}: Text "U.S. Geological Survey" ignored (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Oroville, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Palermo, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ "Oroville Wildlife Area". California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Gridley, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Honcut, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Yuba City, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Olivehurst, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ a b United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Nicolaus, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: Sacramento River Flood Control Project Weirs and Flood Relief Structures" (PDF). California Department of Water Resources. Dec 2010. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ "Feather River Wildlife Area". California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Verona, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (USGS). "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map: Knights Landing, California quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ James, L. Allan; et al. (2009). "Historical channel changes in the lower Yuba and Feather Rivers, California: Long-term effects of contrasting river-management strategies" (pdf). Geological Society of America. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "6.3 Geology, Geomorphology, and Soils" (pdf). Upper North Fork Feather River Hydroelectric Project, Draft Environmental Impact Report. Nov 2014. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ a b Busacca, Alan J.; et al. (1989). "U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1590-G: Late Cenozoic Stratigraphy of the Feather and Yuba Rivers Area, California, with a Section on Soil Development in Mixed Alluvium at Honcut Creek" (pdf). Retrieved 2018-11-05.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Bryan, Kirk (1923). [https%3A%2F%2Fwww.waterboards.ca.gov%2Fwaterrights%2Fwater_issues%2Fprograms%2Fbay_delta%2Fdocs%2Fcmnt081712%2Fsldmwa%2Fbryangroundwaterforirrigationinthesacramentovalley.pdf "USGS Water-Supply Paper 495: Geology and ground-water resources of Sacramento Valley, California"] (PDF). Government Printing Office. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "4.6 Geology and Soils" (PDF). Rio d'Oro Specific Plan EIR. Butte County, California. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ a b Merriam, Kyle; et al. (Oct 2013). "A summary of current trends and probable future trends in climate and climate-driven processes in the Sierra Cascade Province, including the Lassen, Modoc, and Plumas National Forests" (PDF). Upper Feather River Integrated Regional Water Management Program. Retrieved 2018-11-06.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Buer, Koll (Apr 2003). "Physiographic description of the SP-G1 and SP-G2 study areas" (PDF). California Department of Water Resources. Retrieved 2018-11-06.

- ^ https://nwis.waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/monthly/?referred_module=sw&site_no=11425000&por_11425000_10798=2209699,00060,10798,1942-04,1983-09&start_dt=1942-04&end_dt=1967-09&format=html_table&date_format=YYYY-MM-DD&rdb_compression=file&submitted_form=parameter_selection_list

- ^ https://nwis.waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/monthly/?referred_module=sw&site_no=11425000&por_11425000_10798=2209699,00060,10798,1942-04,1983-09&start_dt=1967-10&end_dt=1983-09&format=html_table&date_format=YYYY-MM-DD&rdb_compression=file&submitted_form=parameter_selection_list

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=GK02AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA27

- ^ https://water.ca.gov/LegacyFiles/floodmgmt/fmo/docs/LFRCMP-Final-June2014.pdf

- ^ https://swfsc.noaa.gov/publications/FED/00743.pdf

- ^ https://caltrout.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/CV-SPRING-CHINOOK-SALMON-final.pdf

- ^ a b https://deltarevision.com/maps/fish/nmfs_exh4_yoshiyama_etal_1998.pdf

- ^ a b http://www.sjrdotmdl.org/concept_model/phys-chem_model/documents/300001740.pdf

- ^ http://cahatcheryreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Feather%20Steelhead%20Program%20Report%20June%202012.pdf

- ^ https://www.plumascounty.us/254/Northern-Maidu

- ^ http://www.placercountyhistoricalsociety.org/index_htm_files/The%20Nisenan%20People.pdf

- ^ https://www.google.com/books/edition/Game_Bulletin/2EI5AQAAMAAJ

- ^ https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_of_the_Sierra_Nevada/L25ywC4Cv94C

- ^ https://www.google.com/books/edition/California_Place_Names/ibMwDwAAQBAJ

- ^ https://www.google.com/books/edition/Gold_Rush_of_California/VyW6C4hRvCIC

- ^ https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/california/bidwell_bar/#:~:text=Bidwell%20Bar%20History,received%20a%20post%20in%201851.

- ^ https://westernmininghistory.com/articles/271/page1/

- ^ https://yankeehillhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Concow-Indians-Part-1.pdf

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20110718231502/http://www.plumascounty.org/PDF/7Wonders.pdf

- ^ https://cepsym.org/Sympro1997/Roos.pdf

- ^ https://www.sej.org/sites/default/files/SacbeeOroville0514.pdf

- ^ https://pubs.usgs.gov/wsp/1650a/report.pdf

- ^ https://water.ca.gov/About/History

- ^ https://www.watereducation.org/aquapedia/state-water-project

- ^ http://archives.csuchico.edu/digital/collection/coll11/id/1893

- ^ https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/waterrights/water_issues/programs/water_quality_cert/unffr_ferc2105.html#:~:text=The%20five%20powerhouses%20include%20eight,(1%2C134%2C016%20acre%2Dfeet).

- ^ https://www.ferc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-04/06-14-19-DEIS.pdf

- ^ https://southfeather.com/assets/2011/12/DEIS.pdf

- ^ https://www.pge.com/en_US/safety/electrical-safety/safety-initiatives/desabla/desabla-centerville-hydroelectric-facility.page

- ^ https://www.google.com/books/edition/Federal_Power_Commission_Reports/eqkUErGCOBcC

- ^ https://www.calwild.org/portfolio/fact-sheet-middle-fork-feather-wild-scenic-river/

- ^ https://water.ca.gov/Programs/State-Water-Project/SWP-Facilities/Oroville

- ^ https://www.google.com/books/edition/Decisions_of_the_Railroad_Commission_of/Oh04AAAAIAAJ

- ^ https://www.bwgwater.com/about

- ^ https://buttewaterdistrict.org/