User:Rikstar/Sandbox

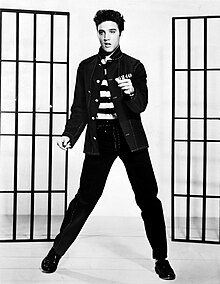

Elvis Presley | |

|---|---|

Elvis in 1970 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Elvis Aaron Presley[1] |

| Also known as | Elvis, The King, The King of Rock 'n' Roll, Elvis the Pelvis, The Hillbilly Cat[2] |

| Genres | Rock & roll, pop, rockabilly, Blues, Country. |

| Occupation(s) | Singer, musician, actor |

| Instrument(s) | Vocals, guitar, piano |

| Years active | 1954–1977 |

| Labels | Sun, RCA Victor |

| Website | Elvis.com |

Elvis Aaron Presley[1][3] (January 8, 1935 – August 16, 1977; middle name sometimes written Aron)a was an American singer, actor and musician He is commonly known simply as "Elvis", or as "The King of Rock 'n' Roll".

In 1954, Presley began his career as one of the first performers of rockabilly, an uptempo fusion of country and rhythm and blues with a strong back beat. His novel versions of existing songs, mixing "black" and "white" sounds, made him popular—and controversial[4][5]—as did his uninhibited stage and television performances. He recorded songs in the rock and roll genre, with tracks like "Hound Dog" and "Jailhouse Rock" later embodying the style. Presley had a versatile voice[6] and had unusually wide success encompassing other genres, including gospel, blues, country, ballads and pop. To date, he has been inducted into four music halls of fame.

In the 1960s, Presley made the majority of his thirty-one movies. In 1968, he returned to playing live in a television special,[7] and later performed across the U.S., notably in Las Vegas. In 1973, Presley staged the first global live concert via satellite (Aloha from Hawaii).[8] Throughout his career, he set records for concert attendance, television ratings and recordings sales.[9] He is one of the best-selling and most influential artists in the history of popular music. Health problems and drug dependency[10] led to his death at age 42.

Early years: Tupelo[edit]

Elvis Presley was one of twins born to Vernon Elvis Presley (April 10, 1916–June 26, 1979) and Gladys Love Smith (April 25, 1912 – August 14, 1958). Elvis' brother, Jesse Garon, was stillborn. The Presleys were not well-off and lived in a two-room shotgun house built by Vernon.

The Presley family attended the Assembly of God church[11] which exposed the young Elvis to his earliest musical influences: "Since I was two years old, all I knew was gospel music. That music became such a part of my life it was as natural as dancing. A way to escape from the problems. And my way of release."[12]

On October 3, 1945, at age ten, he made his first public performance in a singing contest at the Mississippi-Alabama Fair and Dairy Show at the suggestion of his teacher, Mrs. Grimes.[13] The young Presley had to stand on a chair to reach the microphone and sang Red Foley's "Old Shep." He came fifth, winning $5 and a ticket to all the Fair rides.[14]

In 1946, for his eleventh birthday, Presley received his first guitar.[15] Vernon's brother, Vester, gave Elvis basic guitar lessons.[13]

The young Presley frequently listened to local radio; his first musical hero was family friend Mississippi Slim, a hillbilly singer with a radio show on Tupelo’s WELO. Presley performed occasionally on Slim’s Saturday morning show, Singin’ and Pickin’ Hillbilly. Sixth grade friend, James Ausborn (Slim’s brother) claims Presley was "crazy" about music[16] J. R. Snow, son of 1940s country superstar Hank Snow, recalls that even as a young man Presley knew all of Hank Snow’s songs, "even the most obscure".[17] Presley himself said he also loved records by Sister Rosetta Thorpe, Roy Acuff, Ernest Tubbs, Ted Daffan, Jimmie Rodgers, Jimmy Davis and Bob Wills.[18]

Move to Memphis[edit]

In 1949, the Presleys moved to Lauderdale Courts, a public housing development in one of Memphis' poorer sections. Presley practiced playing guitar in the laundry room and also played in a five-piece band with other tenants.[19] He also attended the local branch of the Assembly of God and later, the East Trigg Baptist Church, a black congregation. He was later an audience member at all-night white—and black—"gospel sings" in downtown Memphis.[20]

Presley visited record stores that had jukeboxes and listening booths, playing old records and new releases for hours. Memphis Symphony Orchestra concerts at Overton Park were another Presley favorite, along with the Metropolitan Opera. His small record collection included Mario Lanza and Dean Martin. Presley later said: "I just loved music. Music period."[16]

Many of his future recordings were inspired by his Christian faith; throughout his life—in the recording studio, in private, or after concerts—Presley joined with others singing and playing gospel music at informal sessions.[21] The Southern Gospel singer Jake Hess was also one of Presley's favorite singers and was a significant influence on his singing style.[22] Memphis had a strong tradition of blues music and Presley went to blues as well as hillbilly venues. Other recordings would be influenced by local African American composers and recording artists, including Arthur Crudup and Rufus Thomas.[23] B.B. King has recalled that he knew Presley before he was popular when they both used to frequent Beale Street.[24]

Generally considered to be a shy child who sometimes stuttered, as Presley grew up he bucked the fashions of the times by growing his hair and sideburns and dressing in the flashy clothes, favored by mainly black clientele, of Lansky Brothers on Beale Street.[25] In the conservative Deep South of the 1950s, the young Elvis occasionally drew unwanted attention because of his appearance or his demeanor.[19][26] Regardless of any unpopularity or shyness, he was a contestant in L. C. Humes High School's 1952 "Annual Minstrel Show"[19] and came first by receiving the most applause. His prize was to sing encores, including "Cold Cold Icy Fingers" and "Till I Waltz Again With You".[27]

After leaving school, Presley had several jobs; his third was driving a truck for a firm in Memphis.[28]

First recordings: 1954-1955[edit]

On July 18, 1953, Presley went to Sun Studio's Memphis Recording Service to record "My Happiness" and "That's When Your Heartaches Begin", supposedly a present for his mother.[29] Sun Records' assistant Marion Keisker is said to have asked him who he sounded like. Presley's apparent response was: "I don't sound like nobody."[30] On January 4, 1954, he cut a second acetate. At the time, Sun Records boss Sam Phillips was hoping to find someone who could deliver a blend of black blues and boogie-woogie music; he thought it would be very popular among white people.[31] Keisker eventually called Presley back to try out a demo, and he sang other material he knew.[32] Phillips recalls Presley being very nervous.[33]

Unfazed, Phillips invited local musicians Winfield "Scotty" Moore and Bill Black to audition Presley. A studio session was planned.[34] During a recording break, at which Presley began "acting the fool" with Arthur Crudup's "That's All Right (Mama)",[35] Phillips quickly got them all to restart, and began taping. This was the (rockabilly) sound he had been looking for.[36] The group recorded other songs, including Bill Monroe's "Blue Moon of Kentucky". After the session, according to Scotty Moore, Bill Black remarked on the controversial nature of the sound they had all produced: "Damn. Get that on the radio and they'll run us out of town".[37]

"That's All Right"b was aired early in July, 1954, by DJ Dewey Phillips.[38] Presley is said to have been so nervous about the song's reception that he chose to hide in his favorite movie theater.[39] Listeners to the show began phoning in, eager to find out who the singer was. The interest was such that Phillips played the demo again and again, and he wanted to interview the singer.[39] Presley was found by his parents and, excited by the response, arrived at the station breathless. During the interview, Phillips asked Presley what high school he attended—to clarify Presley's color for listeners who assumed he must be black.[40] The first release of Presley's music featured "That's All Right" and "Blue Moon of Kentucky". With Presley's version of Monroe's song consistently rated higher, both sides began to chart across the South.[41] The singer recorded some twenty songs at Sun in just over a year.

Early performances[edit]

Presley gave performances in July, 1954 at the Bon Air club, a rowdy music venue in Memphis, where the band was not well-received.[42] On July 30 the trio, billed as The Blue Moon Boys, made their first paid appearance, at the Overton Park Shell, with Slim Whitman headlining.[43] With a natural feel for rhythm, Presley's shook his legs when performing: his wide-legged pants emphasizing his leg movements, apparently causing females in the audience to go "crazy".[44] Presley was aware of the cause of the audience's reaction and consciously incorporated similar movements into future shows.[45]

DJ and promoter Bob Neal became the trio's manager (replacing Scotty Moore). Moore and Black then appeared regularly with Presley at The Eagle's Nest.[42] Presley debuted at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville on October 2; Hank Snow introduced Presley on stage. He performed "Blue Moon of Kentucky" but received only a polite response. Afterwards, the singer was upset when allegedly told by the Opry's Jim Denny: "Boy, you’d better keep driving that truck,"[46] though others deny it was Denny who made that statement.[47]

The trio began touring extensively across the South, performing anywhere they could, including football fields. Country music promoter and manager Tillman Franks booked Presley for the Louisiana Hayride on October 16. Before Franks saw Presley, he referred to him as "that new black singer with the funny name".[48] During Presley's first set, the reaction was muted; Franks then advised Presley to sing with abandon for the second set. House drummer D.J. Fontana (who had worked in strip clubs) complemented Presley's movements with accented beats. Bill Black also took an active part in encouraging the audience, and the crowd became more responsive.[49][50] Also in October, 1954, Presley toured with Bill Haley. Like Franks, Haley felt Presley had a natural feeling for rhythm, and advised him to sing fewer ballads if he wanted to wow the crowds.[51]

According to one source, Presley's audiences at that time had never before heard or seen anyone who performed like him. "The shy, polite, mumbling boy gained self-confidence with every appearance... People watching the show were astounded and shocked, both by the ferocity of his performance, and the crowd’s reaction to it... Roy Orbison saw Presley for the first time in Odessa, Texas: 'His energy was incredible, his instinct was just amazing... I just didn’t know what to make of it. There was just no reference point in the culture to compare it.'"[52] Sam Phillips said Presley "put every ounce of emotion ... into every song, almost as if he was incapable of holding back."[53]

By August 1955, after many months of touring, ten sides had been released by the Sun Studio credited to "Elvis Presley, Scotty and Bill". However, the musical style he was developing was proving hard to categorize; he was billed or labeled in the media as "The King of Western Bop", "The Hillbilly Cat" and "The Memphis Flash".[54]

On August 15, 1955, "Colonel" Tom Parker became Presley's manager.[55] Several record labels had shown interest in signing Presley, and on November 21, 1955, Parker and Phillips negotiated a deal with RCA Victor Records to acquire Presley's Sun contract for an unprecedented $35,000[56] (Presley, at 20, was officially still a minor, so his father had to sign the contract).[57]

To boost earnings for himself and Presley, Parker cut a deal with Hill and Range Publishing Company to create two separate entities—"Elvis Presley Music, Inc" and "Gladys Music"—to handle all of Presley's songs and accrued royalties. The owners of Hill & Range, the Aberbachs, agreed to split the publishing and royalties rights of each song equally with Presley. Hill & Range, Presley or Colonel Parker's partners then had to convince unsecured songwriters that it was worthwhile for them to give up one third of their due royalties in exchange for Presley recording their compositions. One result of these dealings was the appearance of Presley's name as co-writer of some songs he recorded, even though Presley never had any hand in the songwriting process.[58]

By December 1955, RCA had begun to heavily promote its newest star, and by the month's end had re-released all five of his Sun singles.[59]

1956 Breakthrough[edit]

On January 10, Presley made his first recordings for RCA in Nashville, Tennessee.[60] The session produced five songs, including "Heartbreak Hotel", a new song inspired by a real suicide, which Presley liked as soon as he heard it.[61] RCA Victor executives in New York were apparently so put off by the songs, they wanted the session to be re-done. Producer Steve Scholes successfully argued against the move, and "Heartbreak Hotel" was released on January 27.[61] By April it had hit number one in the U.S. charts, selling in excess of one million copies. On January 30, at RCA's New York Studio,[60] Presley recorded another eight songs, including "My Baby Left Me" and "Blue Suede Shoes", the first arrangements by Presley that could be called "rock and roll".

On March 23, RCA Victor released Elvis Presley, his first album. Like the Sun recordings, the majority of the tracks were country songs.[62] The album went on to top the pop album chart for 10 weeks.[60]

In 1956, Colonel Parker sought much wider exposure for Presley, on television, and he performed six Dorsey Brothers' Stage Shows, a single Steve Allen Show and two Ed Sullivan Shows, but it was his second appearance on The Milton Berle Show (June 5) that aroused most controversy. He performed "Hound Dog"[63] and Presley's "gyrations" were described in the press as "vulgar" and "obscene".[5][64] Questioned later about the controversy, Presley said: "... you can't help but move to [Rock and roll music]. That's what happens to me. I have to move around ..."[65] In August, even before performing, a judge branded Presley a "savage" and threatened to arrest him if he moved his body on stage in Jacksonville. Throughout the show (which was filmed by police), he kept still as ordered, but wiggled a finger in mockery at the ruling.[66] After his Milton Berle performance, Presley was dubbed "Elvis the Pelvis", which he thought was one of the most childish expressions he'd ever heard from an adult.[67]

By the spring of 1956, Presley had become popular nationwide as fans, mainly teenagers, flocked to his concerts. Many shows ended in a riot,[68] with white, apparently jealous, teenage boys instigating the trouble. In Lubbock, Texas, a teenage gang fire-bombed Presley's car.[69] At the second of two concerts he performed back in Tupelo for the 1956 Mississippi-Alabama Fair and Dairy Show, fifty National Guardsmen were added to the police security to prevent crowd trouble.[70]

However, at the New Frontier Hotel and Casino on the Las Vegas Strip, Presley's shows were so badly received by critics and the conservative, middle-aged guests, that his manager cut short the engagement from four weeks to two.[71]

To many Middle American adults, the singer was "the first rock symbol of teenage rebellion. ... they did not like him, and condemned him as depraved. Anti-Negro prejudice doubtless figured in adult antagonism. Regardless of whether parents were aware of the Negro sexual origins of the phrase 'rock 'n' roll', Presley impressed them as the visual and aural embodiment of sex."[72] A critic for the New York Daily News wrote that popular music "has reached its lowest depths in the 'grunt and groin' antics of one Elvis Presley", and the Jesuits denounced him in its weekly magazine, America.[73] Even Frank Sinatra was scathingly critical of Presley: "His kind of music is deplorable, a rancid smelling aphrodisiac. It fosters almost totally negative and destructive reactions in young people."[74] Presley responded: "... [Sinatra] is a great success and a fine actor, but I think he shouldn't have said it. ... [rock and roll] ... is a trend, just the same as he faced when he started years ago."[75]

Presley also had ambitions to be a serious actor and admired screen stars like James Dean, Marlon Brando and Rod Steiger.[76] Parker saw a film career as huge earnings opportunity and secured a lucrative seven-year contract with Paramount Pictures and on April 1, Presley screen-tested for his first motion-picture, a musical western, Love Me Tender. The original title—The Reno Brothers—was changed to capitalize on the advanced sales of the song "Love Me Tender". Released in November, the film was panned by critics, but proved popular amongst his fans and did well at the box office.[77]

1957-58[edit]

Presley's popularity brought increased concerns over privacy and security. Graceland, a mansion with several acres of land twelve miles south of downtown Memphis, was bought and renovated in 1957. It became Presley's primary residence until his death.[78]

Presley made two films in 1957; Loving You and Jailhouse Rock. The latter featured the acclaimed dance sequence to the rock and roll song Jailhouse Rock, which Presley choreographed himself.[79] Presley also made his final (of three) Ed Sullivan shows in January, 1957.

In 1957, despite Presley's demonstrable respect for "black" music and performers,[80] he faced accusations of racism. He was alleged to have said in an interview: "The only thing Negro people can do for me is to buy my records and shine my shoes." An African American journalist at Jet magazine subsequently pursued the story. On the set of Jailhouse Rock, Presley denied saying, or ever wanting to make, such a racist remark. The Jet journalist found no evidence that the remark had ever been made, but did find testimony from many individuals indicating that Presley was anything but racist.[81] Despite the remark being wholly discredited at the time, it was still being used against Presley decades later.[82]

On December 20, 1957, Presley received his draft notice. He was granted a deferment to finish filming King Creole, which featured songs including "Hard Headed Woman" and "Trouble". Inducted on March 24, 1958, Private Presley completed basic training at Fort Hood, Texas and was posted to Friedberg, Germany with the 3rd Armored Division, where his service started on October 1.[83]

As Presley's fame grew, his mother's health deteriorated through her abuse of drink and diet pills. Doctors had diagnosed hepatitis, and her condition worsened. Presley was granted emergency leave from the Army to visit her, arriving in Memphis on August 12. Two days later his mother died, aged forty-six. Presley, having always been unusually close to her, was distraught, "grieving almost constantly" for days.[84]

Presley's record sales grew quickly throughout the late 1950s, with hits like "All Shook Up", "(Let me Be Your) Teddy Bear" and "Too Much". He also released Elvis' Christmas Album in 1957, which would later become the top-selling holiday release of all time, according to the RIAA.[85]

1958-60[edit]

Presley did not join 'Special Services' to avoid certain army duties.[86] Fellow soldiers have attested to Presley's wish to be seen as an able, ordinary soldier, and to his generosity while in the service. To supplement meager clothing supplies, Presley bought an extra set of fatigues for everyone in his outfit. He also used his Army pay to make charitable donations, and to help purchase all the TV sets for personnel on the base at that time.[87]

He continued to receive massive media coverage, with much speculation echoing Presley's own concerns about his enforced absence damaging his career. However, early in 1958, RCA Victor producer Steve Sholes and Freddy Bienstock of Hill and Range (Presley's main music publishers) had both pushed for recording sessions and strong song material, the aim being to release regular hit recordings during Presley's two-year hiatus.[88] Hit singles duly followed during Presley's army service, like "One Night", "I Got Stung" and "(Now and Then There's) A Fool Such as I", as did hit albums of old material, including Elvis' Golden Records and A Date With Elvis.

In Germany, a sergeant apparently introduced Presley to amphetamines, which staved off sleep during shifts. Army friends around Presley also began taking them, "if only to keep up with Elvis, who was practically evangelical about their benefits."[16] The Army also introduced Presley to karate—something which he studied seriously. Presley would later include karate moves he learned in his performances as an actor and singer.[89]d

Presley returned to the U.S. on March 2, 1960, and was honorably discharged with the rank of sergeant on March 5.[90] Back on U.S. soil, the train which carried him from New Jersey to Memphis was mobbed all the way, with Presley being called upon to appear at scheduled stops to please his fans.[91]

1960: first post-Army recordings[edit]

The first post-Army recordings, made in Nashville (March 20, 1960), were witnessed by all of the significant recording industry figures involved with Presley; none had heard him sing for two years, and there were inevitable concerns about him being able to recapture his previous success.[92] The session was the first at which Presley was taped using a three-track recording machine, which allowed better sound quality, postsession remixing and stereophonic recording.[92]

This session, and a further one in April, yielded some of Presley's best-selling songs. "It's Now or Never" ended with Presley "soaring up to an incredible top G sharp ... pure magic."[93] His voice on "Are You Lonesome Tonight?" has been described as "natural, unforced, dead in tune, and totally distinctive."[93]

Although some tracks were uptempo, none could be described as "rock and roll", and many of them marked a significant change in musical direction.[93] Most tracks found their way on to an album—Elvis is Back!—described by one critic as "a triumph on every level... It was as if Elvis had... broken down the barriers of genre and prejudice to express everything he heard in all the kinds of music he loved".[94] The album was also notable because of Homer Boots Randolph's acclaimed saxophone playing on the blues songs "Like A Baby" and "Reconsider Baby", the latter being described as "a refutation of those who do not recognize what a phenomenal artist Presley was."[93] Music critic Henry Pleasants has described Presley's voice as having "an extraordinary compass... and a very wide range of vocal color", enabling him to sing in an exceptional range of musical genres. "In ballads and country songs he belts out full-voiced high G's and A's that an opera baritone might envy. He is a naturally assimilative stylist with a multiplicity of voices—in fact, Elvis' is an extraordinary voice, or many voices."[6]

Movie career continues: 1960 - 1967[edit]

Presley stopped live performing after his Army service with the exception of a guest appearance on Frank Sinatra's TV special It's Nice To Go Traveling, now more commonly known as Welcome Home Elvis (1960). He also performed three charity concerts—two in Memphis and one in Pearl Harbor (1961).[95]

The seven-year movie contract of 1956 was drawn up with Parker's eye on long-term earnings, rather than Presley's personal acting ambitions.[96] The singer would later star with several established or up-and-coming actors, including Walter Matthau, Angela Lansbury, Charles Bronson, Barbara Stanwyck and Mary Tyler Moore. Although Presley was praised by directors, like Michael Curtiz, as polite and hardworking (and as having an exceptional memory), "he was definitely not the most talented actor around."[97]

Critic Bosley Crowther of the New York Times said of his role in King Creole: "This boy can act". Director Joe Pasternak believed Presley could develop into a better actor, if he was given roles in better pictures.[98] However, in 1964, Hal Wallis' admitted to the press that the financing of such quality productions as his Becket was only possible by making a series of profitable B-movies starring Presley. Elvis branded Wallis "a double-dealing sonofabitch", realizing there had never been any intention to let him develop into a serious actor.[99]

According to life-long friend George Klein, Presley was offered better roles, including a personal request by Robert Mitchum to play the lead in Thunder Road (1958). He was also offered lead roles in West Side Story (1961) and Midnight Cowboy (1969).[100] In 1974, Barbra Streisand approached Presley to star with her in the remake of A Star is Born. In each case, any ambitions the singer may have had to play such parts were thwarted by his manager.[101]

The movies Presley did make in the 1960s were critical flops.[102] However, his films were undoubtedly popular with fans; his 1960s films alone, and their soundtracks, grossed some $280 million.[103] Blue Hawaii (1961) was even credited with boosting the new state's tourism. Some of his most enduring and popular songs came from such light-weight vehicles, like "Can't Help Falling in Love" (from Blue Hawaii), "Return to Sender (from Girls! Girls! Girls!) and "Viva Las Vegas."[104]

Elvis on celluloid was the only chance for his worldwide admirers to see him, in the absence of live appearances. The only time he toured outside of the U.S. was in Canada in 1957. Colonel Parker's concerns about his U.S. citizenship (he was a Dutch immigrant) may have been an important factor in Presley's popularity not being exploited abroad by live tours. By 1967, Parker had negotiated a contract that gave him 50% of Presley's earnings. Parker's excessive gambling appears to have been increasingly influential in signing Presley to commercially lucrative contracts in the U.S., with little regard for artistic merit.[105]

By the late sixties, the Hippie movement had developed and musical acts like Jefferson Airplane, Sly and the Family Stone, Grateful Dead, The Doors and Janis Joplin were dominating the airwaves.[106] Priscilla Presley recalls: "He blamed his fading popularity on his humdrum movies" and "... loathed their stock plots and short shooting schedules." She also notes: "He could have demanded better, more substantial scripts, but he didn't."[107]

As well as the formulaic movie songs, Presley also recorded better material, including "There's Always Me", "She's Not You", "Suspicion," "Little Sister", "(You're the) Devil in Disguise" and "It Hurts Me." In 1966 he recorded Bob Dylan's "Tomorrow is a Long Time", which RCA Victor relegated to a bonus track on the Spinout movie album. He also produced two gospel albums: His Hand in Mine (1960) and How Great Thou Art (1966), the latter winning a Grammy. In 1967, he recorded other quality songs, including "Guitar Man", "Hi-Heel Sneakers" and "You Don't Know Me".

Presley, who by now had millions of adoring fans, had been linked with many women since he achieved fame, though some sources argue that the number of his sexual liaisons has been exaggerated.[108][109] Cybill Shepherd, Judy Spreckels, June Juanico, Cassandra Peterson ("Elvira"), Peggy Lipton and Lori Williams are some who have revealed details of their intimate encounters with Presley, which vary from accounts of simply talking and watching television, to having sexual intercourse with the star.

Ann-Margret (Presley's co-star in 1963's Viva Las Vegas) refers to Presley as her "soulmate" but has revealed little else about their relationship.[110] A publicity campaign about Presley and Margret's romance was launched during the filming of Viva Las Vegas,[111] which helped to increase Margret's popularity.[112][113] Presley apparently dated many female co-stars for publicity purposes.[114]

Presley married Priscilla Beaulieu on May 1, 1967 (Their only child, Lisa Marie, was born on February 1, 1968).

1968 Comeback[edit]

The single "Guitar Man" failed to enter the U.S. Top 40 in 1968, and any soundtrack albums also sold poorly. "Good Luck Charm" had been Presley's last U.S. number one single almost six years earlier.[115]

Colonel Parker arranged for Presley to appear in his own television special. He struck a deal with NBC which included the network's commitment to financing a future Presley movie—something increasingly difficult to achieve at the time.[115]

The special was first aired on December 3, 1968 as a Christmas telecast called simply Elvis. Later dubbed the '68 Comeback Special by fans and critics, the show featured some lavishly staged studio productions, a recurrent theme being based on "Guitar Man", a song which echoed Presley's musical beginnings. Other songs however, were performed live with a band in front of a small audience—Presley's first live appearance as a performer since 1961. The live segments saw Presley clad in black leather, singing and playing guitar in an uninhibited style—reminiscent of his rock and roll days. Highlights include "Trying To Get To You", Baby, What You Want Me To Do, "One Night", "Tiger Man" and "If I Can Dream". Scotty Moore and D.J. Fontana accompanied Presley during these live sessions.

Jon Landau in Eye magazine remarked: "There is something magical about watching a man who has lost himself find his way back home. He sang with the kind of power people no longer expect of rock 'n' roll singers. He moved his body with a lack of pretension and effort that must have made Jim Morrison green with envy."[7] Its success was helped by director and co-producer, Steve Binder, who worked hard to reassure a singer so nervous that he occasionally wanted to walk away from the project.[116] Binder also stood up to a belligerent Parker and managed to produce a show that was not just a bland hour of Christmas songs, as Parker had originally intended.[117][118]

According to Scotty Moore, a reinvigorated Presley spoke to him and D.J. Fontana afterwards and privately asked them if they would accompany him on a tour of Europe. They agreed, but Moore never saw or worked with Presley again.[119]

1969-1972[edit]

By January, 1969, one of the key songs written for Elvis, "If I Can Dream", reached number 12,[115] and the soundtrack made the Top 10. The special had captured 42 percent of the total viewing audience, and was NBC's number one-rated show that season.[115]

Revitalized, Presley engaged in a prolific series of recording sessions at American Sound Studios, which lead to the acclaimed From Elvis in Memphis.[120] It was followed by an equally well-received series of tracks on From Memphis To Vegas/From Vegas To Memphis, a double-album. The same sessions produced the hit singles "In the Ghetto", "Suspicious Minds", "Kentucky Rain" and "Don't Cry Daddy". The singer also made his final movie, Change of Habit (1969).

Following the success of Elvis, offers for Presley to perform live came in from around the world,[121] but Parker turned them down. By May, 1969, the brand new International Hotel in Las Vegas announced that it had booked Presley for fifty-seven shows.[121]

Despite prestigious backing musicians, Presley was nervous, but the subsequent reviews were comparable with those for his television special. Newsweek commented: "There are several unbelievable things about Elvis, but the most incredible is his staying power in a world where meteoric careers fade like shooting stars."[122] Rolling Stone declared Presley to be "supernatural, his own resurrection", while Variety proclaimed him a "superstar".[33]

In January 1970, Presley returned to the International Hotel for a month-long engagement. RCA Victor released highlights of it on the album On Stage - February 1970.[123] In late February, Presley performed six attendance-breaking shows at the Houston Astrodome, Texas.[124] In August, MGM filmed rehearsal and concert footage for a documentary: Elvis - That's The Way It Is. He wore a jumpsuit—a garment that would become a trademark of Presley's live performances in the 1970s. Although he had new hit singles in many countries, some were still critical of his song choices and accused him of being distant from trends within contemporary music.[125]

After closing his Las Vegas engagements on September 7, Presley embarked on his first concert tour since 1958.

On December 21, 1970, Presley had engineered a somewhat bizarre meeting with President Richard Nixon at the White House to express his patriotism, and his contempt for the hippie drug culture. He also apparently wished to obtain a Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs badge to add to similar items he had begun collecting. He offered to "infiltrate hippie groups" and claimed that The Beatles had "made their money, then gone back to England where they fomented anti-American feeling."[126] (Presley and his friends had had a four-hour meeting with The Beatles five years earlier). Nixon was bemused by his encounter with the singer, and twice expressed his concern to Presley that the singer needed to "retain his credibility".[126][127] Ringo Starr later said he found it very sad to think Presley held such views. Paul McCartney said also that he "felt a bit betrayed ... The great joke was that we were taking drugs, and look what happened to [Elvis]",[128] a reference to Presley's own abuse of drugs.

Presley had been taking drugs of some form for many years. Priscilla Presley writes that by 1962, the singer was taking placidyls to combat severe insomnia in ever-increasing doses and later took Dexedrine to counter the sleeping pills' after-effects. Dr. George C. Nichopoulos, who became Presley's personal physician in 1967, has noted how Presley did not see himself as a common everyday "junkie" because he was using medication prescribed by doctors.[129]

On January 16, 1971 Presley was named 'One of the Ten Outstanding Young Men of the Nation' by the U.S. Junior Chamber of Commerce (The Jaycees).[130] That summer, the City of Memphis named part of Highway 51 South "Elvis Presley Boulevard",[130] and he won the Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (the organization that presents Grammy awards).[131]

In April 1972, MGM again filmed Presley, this time for a documentary, Elvis on Tour, which won a 1972 Golden Globe Award. A fourteen-date tour started with an unprecedented four consecutive sold-out shows at Madison Square Garden, New York. RCA again taped the shows for a live album. After the tour, a 1972 single, "Burning Love", was released—his last top ten hit in the U.S. charts.

Off stage, in spite of his own infidelity, Presley was furious that his wife was having an affair with a mutual acquaintance, Mike Stone, a karate instructor.[33] His rage was such that a bodyguard and school friend, Red West, felt compelled to get a price for Stone's contract killing. West was relieved when Presley decided against it.[132] The Presleys separated on February 23, 1972 and divorced on October 9, 1973, agreeing to share custody of their daughter.

1973-76[edit]

Following his separation, Presley lived with Linda Thompson, a songwriter and one-time Memphis beauty queen, from July 1972 until just a few months before his death.[133]

In January 1973, Presley performed two charity concerts in Hawaii for the Kui Lee cancer foundation (The singer made many other charitable donations throughout his adult life. He also quietly paid hospital bills, bought cars, homes, supported families, paid off debts, etc., for friends, family and total strangers).[134] The second "Aloha from Hawaii" concert was the world's first live concert satellite broadcast, reaching at least a billion viewers live and a further 500 million on delay. The show's album went to number one and spent a year in the charts, and was Presley's last U.S. Number One album during his lifetime.[8]

After his divorce, Presley became increasingly unwell, with prescription drugs continuing to affect his appearance, mood and his stage act. His diet and eating patterns had always been unhealthy, and he now had significant weight problems.[135] He overdosed twice on barbiturates, spending three days in a coma in his hotel suite after the first.[129] According to Dr. Nichopoulos, the singer was "near death" in November 1973 because of side effects of Demerol addiction. Nichopoulos notes that the subsequent hospital admission "was crazy", because of the enormous attention Presley attracted, and the measures necessary to protect his medical details. Even hospital laboratory technicians were exploiting Presley's ill-health, by secretly selling samples of his blood and urine.[136]

In his book, Elvis: The Final Years, Jerry Hopkins writes: "Elvis' health plummeted as his weight ballooned." At a University of Maryland concert on September 27, 1974, band members were greatly concerned. Guitarist John Wilkinson recalled: "'... It was obvious he was drugged, that there was something terribly wrong with his body. It was so bad, the words to the songs were barely intelligible. ... We were in a state of shock.'"

Despite this, his "thundering" live version of "How Great Thou Art" won him a Grammy award in 1974.[137] Presley won three competitive "Grammies" for his gospel recordings: "How Great Thou Art"—the album, as well as the single—and for the album He Touched Me (1972) (He had fourteen nominations during his career, though it has been claimed that Presley was never adequately appreciated by those who give the Grammies).[138]

In April 1974, rumors began that he would actually be playing overseas.[139] A $1m bid came from Australia for him to tour there, but Colonel Parker again refused to consider any notions Presley had of overseas work.[139]

Presley continued to play to sell-out crowds in the U.S.; a 1975 tour ended with a concert in Pontiac, Michigan, attended by over 62,000 fans. However, headlines such as "Elvis Battles Middle Age" and "Time Makes Listless Machine of Elvis" were not uncommon.[140] According to one critic, when Presley made his later appearances in Las Vegas, he appeared "heavier, in pancake make-up... with an elaborate jewelled belt and cape, crooning pop songs ... [He] had become Liberace. Even his fans were now middle-aged matrons and blue-haired grandmothers, ... Mother's Day became a special holiday for Elvis' fans."[141]

On July 13, 1976, Presley's father fired "Memphis Mafia" bodyguards Red West, Sonny West and David Hebler. He had generally distrusted the coterie of old friends and bodyguards who had been close to Presley for many years; he thought they collectively exercised an unhealthy influence over his son.[142] To some observers, it was no wonder that as the singer "slid into addiction and torpor, no one raised the alarm: to them, Elvis was the bank, and it had to remain open."[143] Musician Tony Brown noted the urgent need to reverse Presley's declining health as the singer toured in the mid-1970s. "But we all knew it was hopeless because Elvis was surrounded by that little circle of people... all those so-called friends and... bodyguards."[144] In the "Memphis Mafia"'s defence, Marty Lacker has said: "[Presley] was his own man. ... If we hadn't been around, he would have been dead a lot earlier."[145]

Presley's cousin and friend David Stanley has claimed the bodyguards were fired because of becoming more outspoken about Presley's drug dependency.[146] A "trusted associate" of Presley, John O'Grady, also stated, in agreement with Colonel Parker and Vernon Presley, that the bodyguards' actions were resulting in too many unnecessary lawsuits.[147]

Almost throughout the 1970s, Presley's recording label had been increasingly concerned about making money from Presley material: RCA Victor often had to rely on live recordings because of problems getting him to attend studio sessions. A mobile studio was occasionally sent to Graceland in the hope of capturing an inspired vocal performance. Once in a studio, he could lack interest or be easily distracted; often this was linked to his health and drug problems.[127]

Elvis Presley broke up with Linda Thompson in November 1976 after meeting Ginger Alden. , Ginger Alden became engaged to Elvis in January 1977 and was the person who found his body on August 16, 1977.

1977: final year[edit]

One commentator has written: "Elvis Presley had [in 1977] become a grotesque caricature of his sleek, energetic former self... he was barely able to pull himself through his abbreviated concerts."[148]

In Knoxville, Tennessee on May 20, "there was no longer any pretense of keeping up appearances. The idea was simply to get Elvis out on stage and keep him upright..."[149] Despite his obvious problems and disturbing appearance, shows in Omaha, Nebraska and Rapid City, South Dakota went ahead and were recorded for an album and a CBS-TV special: Elvis In Concert.[150]

His performance in Omaha "exceeded everyone's worst fears... [giving] the impression of a man crying out for help..."[150] According to Guralnick, fans "were becoming increasingly voluble about their disappointment, but it all seemed to go right past Elvis, whose world was now confined almost entirely to his room and his books."[149] Presley's hairdresser, Larry Geller, had initially recommended books on religion and mysticism after hearing Elvis confide his secret worries and anxieties, about missing his mother and the hollowness of life in Hollywood. As long ago as 1964, Presley revealed to Geller: "I swear to God, no one knows how lonely I get and how empty I really feel."[151]

A cousin, Billy Smith, recalled how Presley, in his final years, would sit in his room and chat, recounting things like his favorite Monty Python sketches and his own past japes with friends, but "mostly there was a grim obsessiveness... a paranoia about people, germs... future events", that reminded Smith of Howard Hughes.[152]

A book, Elvis: What Happened? was published just fifteen days before Presley's death. Written by Presley's sacked bodyguards, it was the first exposé to detail Presley's failings, including his years of drug misuse. It was apparently the authors' revenge for them being fired, and also a plea to get Presley to recognize the extent of his drug problems.[153] The singer is said to have been devastated by the book and felt he had been betrayed by close friends.[154]

Presley's final performance was in Indianapolis at the Market Square Arena, on June 26, 1977. According to many of his entourage, it was his best show in a long time.[33]

Another tour was scheduled to begin August 17, 1977, but at Graceland the day before, Presley was found on his bathroom floor by Ginger Alden. According to the medical investigator, Presley had been using the toilet at the time and had "stumbled or crawled several feet before he died."[155] Death was officially pronounced at 3:30 pm at the Baptist Memorial Hospital.

Before his funeral, hundreds of thousands of people lined the streets and many hoped to see the open casket in Graceland. One of Presley's cousins, Bobby Mann,[33] accepted $18,000 to secretly photograph the corpse; the picture duly appeared on the cover of the National Enquirer, making it that paper's largest and fastest selling issue.[156] Two days after the singer's death, a car ran into a crowd of about 2000 fans outside Presley's home, killing two women and critically injuring a third.[157] Among the mourners at the funeral were Ann-Margret (who had remained close to Presley), and his ex-wife.[158] U.S. President Jimmy Carter issued a statement (See 'Legacy').[159]

On Thursday, August 18, following a funeral service at Graceland,[33] Elvis Presley was buried at Forest Hill Cemetery in Memphis, next to his mother. After an attempt to steal his body on August 28,[33] Presley's—and his mother's—remains were reburied at Graceland's Meditation Garden in October.[33]

Post mortem observations[edit]

Presley had developed many health problems during his life, some of them chronic.[160] Opinions differ regarding the onset of his drug abuse. He did take (amphetamines) regularly in the army, but Presley's friend Lamar Fike has said: "Elvis got his first uppers from what he stole from his mother. Gladys was given Dexedrine to help her with her 'change of life' problems."[135]

In two laboratory reports filed two months after his death, each indicated "a strong belief that the primary cause of death was polypharmacy," with one report "indicating the detection of fourteen drugs in Elvis' system, ten in significant quantity."[161]

Many doctors had been flattered to be associated with Presley, or had been bribed with gifts. They subsequently supplied him with pills, which simply fed his addictions.[162] The singer allegedly spent at least $1m annually during his latter years on drugs and doctors' fees or inducements.[163] Presley's main physician, Dr. Nichopoulos, was exonerated with regard to Presley's actual death, but in the first eight months of 1977 alone, he was found to have prescribed the singer more than 10,000 doses of sedatives, amphetamines, and narcotics. On January 20, 1980, his license was suspended, but the board of inquiry decided that he had not been unethical because he claimed to have been trying to wean Presley off the drugs. However, in July 1995, his license was permanently revoked after it was found he had improperly dispensed drugs to several patients including Jerry Lee Lewis.[129]

At the first press conference after Presley's death, Medical Examiner Dr. Jerry Francisco offered a cause of death, even though the autopsy was still being performed, and toxicology results were not known. Dr. Francisco dubiously stated that cardiac arrhythmia was the cause of death, a condition that can only be determined in a living person—not post mortem.[10]

In 1994, the autopsy into Presley's death was re-opened. Coroner Dr. Joseph Davis declared: "There is nothing in any of the data that supports a death from drugs [i.e. drug overdose]. In fact, everything points to a sudden, violent heart attack."[129] However, there is little doubt that polypharmacy/Combined Drug Intoxication caused his death.[10]

Legacy[edit]

Elvis Presley's death deprives our country of a part of itself. He was unique and irreplaceable. More than 20 years ago, he burst upon the scene with an impact that was unprecedented and will probably never be equaled. His music and his personality, fusing the styles of white country and black rhythm and blues, permanently changed the face of American popular culture. His following was immense, and he was a symbol to people the world over of the vitality, rebelliousness, and good humor of his country.

Author Samuel Roy has argued: "Elvis' death did occur at a time when it could only help his reputation. Just before his death, Elvis had been forgotten by society."[165]

Biographer Ernst Jorgensen has observed that when Presley died, "it was as if all perspective on his musical career was somehow lost."[166] His latter-day song choices had been seen as poor; many who disliked Presley had long been dismissive because he did not write his own songs. Others complained—incorrectly—that he could not play musical instruments.[167] Such criticism of Presley continues.[82][167][168]

The tabloids had ridiculed Presley's obesity and his kitschy, jump-suited performances. His sixties' film career was mocked. Acknowledgment of his vocal style had been reduced to mocking the hiccuping, vocalese tricks that he had used on some early recordings—and to the way he said "Thankyouverymuch" after songs during live shows.[169] This was only countered by the uncritical adulation of die-hard fans, who had even denied that he looked "fat" before he died.[170] Any wish to understand Elvis Presley—his genuine abilities and his real influence— seemed, according to Jorgenson, "almost totally obscured."[166]

However, in the late 1960s, composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein remarked: "Elvis is the greatest cultural force in the twentieth century. He introduced the beat to everything, music, language, clothes, it's a whole new social revolution... the 60's comes from it."[171] His early music and live performances are credited with helping to lay a commercial foundation which allowed established African American acts of the 1950s to receive due recognition. Performers like Fats Domino, Chuck Berry and Little Richard, came to national prominence after Presley's mix of musical styles was accepted among White American teenagers.[169] Rather than Presley being seen as a white man who 'stole black music', Little Richard argued: "He was an integrator, Elvis was a blessing. They wouldn't let black music through. He opened the door for black music."[171] Gospel and soul singer Al Green agreed, saying; "He broke the ice for all of us."[171]

Other celebrated pop and rock musicians have acknowledged that the young Presley inspired them. The Beatles were all big Presley fans.[172] John Lennon said: "Nothing really affected me until I heard Elvis. If there hadn't been an Elvis, there wouldn't have been a Beatles."[173] Deep Purple's Ian Gillan said: "For a young singer he was an absolute inspiration. I soaked up what he did like blotting paper... you learn by copying the maestro."[174] Rod Stewart declared: "Elvis was the King. No doubt about it. People like myself, Mick Jagger and all the others only followed in his footsteps." Cher recalls from seeing Presley live in 1956 that he made her "realize the tremendous effect a performer could have on an audience."[171] Bob Dylan said: "When I first heard Elvis' voice I just knew that I wasn't going to work for anybody; ... Hearing him for the first time was like busting out of jail."[171]

By 1958, singers obviously adopting Presley's style, like Marty Wilde and Cliff Richard (the so-called "British Elvis"), were rising to prominence in the UK. Elsewhere, France's Johnny Hallyday and the Italians Adriano Celentano and Bobby Solo were also heavily influenced by Presley.[175][176]

Presley's informal jamming in front of a small audience in the '68 Comeback Special is regarded as a forerunner of the so-called 'Unplugged' concept, later popularized by MTV.[177]

Presley has featured prominently in a variety of polls and surveys designed to measure popularity and influence.e The singer has been inducted into four music 'Halls of Fame': the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (1986), the Rockabilly Hall of Fame (1997), the Country Music Hall of Fame (1998), and the Gospel Music Hall of Fame (2001). In 1984, he received the W. C. Handy Award from the Blues Foundation and the Academy of Country Music’s first Golden Hat Award. In 1987, he received the American Music Awards’ first posthumous presentation of the Award of Merit.[178]

Presley has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 7080 Hollywood Boulevard. He was also honored by the Mississippi Blues Commission with a Mississippi Blues Trail historic marker placed in Tupelo, his birth place, in recognition of his contribution to the development of the blues in Mississippi.[179][180]

In 1994, the 40th anniversary of Presley's "That's All Right" was recognized with its re-release, which made the charts worldwide, making top three in the UK.

During the 2002 World Cup a Junkie XL remix of his "A Little Less Conversation" (credited as "Elvis Vs JXL") topped the charts in over twenty countries and was included in a compilation of Presley's U.S. and UK number one hits, Elv1s: 30.

In the UK charts (January 2005), three re-issued singles again went to number one ("Jailhouse Rock", "One Night"/"I Got Stung" and "It's Now or Never"). Throughout the year, twenty singles were re-issued—all making top five.

In the same year, Forbes magazine named Presley, for the fifth straight year, the top-earning deceased celebrity, grossing US$45 million for the Presley estate during the preceding year. In mid-2006, top place was taken by Nirvana's Kurt Cobain after the sale of his song catalogue, but Presley reclaimed the top spot in 2007.[181]

Paul F. Campos has written: "The Elvis cult touches on so many crucial nerves of American popular culture: the ascent of a workingclass boy from the most obscure backwater to international fame and fortune; the white man with the soul of black music in his voice; the performer whose music tied together the main strands of American folk music – country, rhythm and blues, and gospel; and, perhaps most compellingly for a weight-obsessed nation, the sexiest man in America's gradual transformation into a fat, sweating parody of his former self, straining the bounds of a jewel-encrusted bodysuit on a Las Vegas stage. The images of fat Elvis and thin Elvis live together in the popular imagination."[182] The singer continues to be imitated—and parodied—outside the main music industry and Presley songs remain very popular on the karaoke circuit. People from a diversity of cultures and backgrounds work as Elvis impersonators ("the raw 1950s Elvis and the kitschy 1970s Elvis are the favorites.")[183]

In 2002, it was observed:

For those too young to have experienced Elvis Presley in his prime, today’s celebration of the 25th anniversary of his death must seem peculiar. All the talentless impersonators and appalling black velvet paintings on display can make him seem little more than a perverse and distant memory. But before Elvis was camp, he was its opposite: a genuine cultural force... Elvis’s breakthroughs are underappreciated because in this rock-and-roll age, his hard-rocking music and sultry style have triumphed so completely.

Discography[edit]

See also[edit]

- List of best-selling music artists

- List of artists by total number of USA number one singles

- List of artists by total number of UK number one singles

- Honorific titles in popular music

Notes[edit]

- ^Note a : Presley's genuine birth certificate reads "Elvis Aaron Presley" (as written by a doctor). There is also a souvenir birth certificate that reads "Elvis Aron Presley." When Presley did sign his middle name, he used Aron. It reads 'Aron' on his marriage certificate and on his army duffel bag. Aron was apparently the spelling the Presleys used to make it similar to the middle name of Elvis' stillborn twin, Jesse Garon. Elvis later sought to change the name's spelling to the traditional and biblical Aaron. In the process he learned that "official state records had always listed it as Aaron. Therefore, he always was, officially, Elvis Aaron Presley." Knowing Presley's plans for his middle name, Aaron is the spelling his father chose for Elvis' tombstone, and it is the spelling his estate has designated as the official spelling whenever the middle name is used today. His death certificate says "Elvis Aron Presley." This quirk has helped inflame the "Elvis is not dead" conspiracy theories.[1]

- ^Note b : Presley's version dropped the word "Mama" from the title.[38]

- ^Note d : In 1973, Presley was keen to produce a karate movie/documentary, enlisting the help of several top instructors and film-makers. Instructor Rick Husky says: "...Basically [our meeting] never went anywhere... Elvis got up and did some demonstrations with Ed [Parker], you know stumbled around a little bit, and it was very sad." Husky was aware that Presley was "stoned." "Colonel" Parker thought the project was folly—and a drain on their resources—from the start. (Guralnick 1994, p. 531 and in passim). The film footage was finally edited, restored and released as The New Gladiators in 2002.New Gladiators (2002) Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved on 2007-10-12; Susan, King (November 17, 2002). "When Elvis bowed to karate kings" Los Angeles Times. Reprinted in IssacFlorentine.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-12.

- ^Note e : VH1 ranked Presley #8 on its 100 Greatest Artists in Rock and Roll in 1998 while CMT ranked him #15 on CMT's 40 Greatest Men in Country Music. Presley is one of only three artists to make both VH1's and CMT's lists, the others being Johnny Cash and The Eagles.[185][186] Elvis also ranked second for BBC's "Voice of the Century", eighth on Discovery Channel's "Greatest American" list, in the top ten of Variety's "100 Icons of the century", sixty-sixth in The Atlantic Monthly's "100 most influential figures in American history", and third in Rolling Stone's "The Immortals: The Fifty Greatest Artists of All Time" for which he was chosen by Bono.[187][188][189][190][191]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b c (May 9, 2002). "Elvis Presley - the Singer". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- ^ "Elvis Presley 1953–1955 : The Hillbilly Cat". Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- ^ "FAQ: Elvis' middle name, is it Aron or Aaron?" Elvis.com. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ^ See Fensch, Thomas. The FBI Files on Elvis Presley, pp.15-17.

- ^ a b An example of press criticism can be found at Gould, Jack (June 6, 1956). "TV: New Phenomenon" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved on 2007-10-14.

- ^ a b WikiQuote: Elvis Presley

- ^ a b Hopkins 2007, p.215

- ^ a b See "Aloha From Hawaii"

- ^ [Is Elvis the Biggest Selling Recording Artist? - Sorting Out Records Sales Stats & RIAA Rules. http://www.elvis.com/news/full_story.asp?id=131]. Retrieved 2008-10-27.

- ^ a b c "Coverup for a King". Court TV Crime Library. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- ^ Guralnick 1994, p.13

- ^ "[1]" Quoted in How Stuff Works. Retrieved on 2008-11-14.

- ^ a b Stanley and Coffey 1998, p.19

- ^ "Elvis.com Biography"

- ^ (October 14, 2001). "Elvis Presley's First Guitar". Tupelo Hardware. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ a b c Guralnick 1994, p.21

- ^ Guralnick 1994, p.171

- ^ Matthew-Walker 1979, p.3

- ^ a b c Guralnick 1994, p.50

- ^ (August 18, 1997). "Good Rockin'". Newsweek, pp.54-5

- ^ Guralnick 1994, p.461

- ^ http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/jake-hess-549231.html Jake Hess Obituary

- ^ Guralnick, Peter (August 11, 2007). "How Did Elvis Get Turned Into a Racist?" New York Times. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ^ Szatmary, p.35

- ^ Lichter, p.9

- ^ Matthew-Walker 1979, p.5

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Carr-10was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ (1996). "Elvis Presley". history-of-rock.com. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ "Elvis biography: 1935–1957". elvis.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-14.

- ^ "Marion Keisker: Who Discovered Elvis?". elvispresleynews.com. Retrieved on 2008-06-09.

- ^ Miller, p.71

- ^ Lichter, p.12

- ^ a b c d e f g h Everything Elvis, ISBN 0753509601

- ^ "Sam Phillips Sun Records Two". history-of-rock.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-14.

- ^ Guralnick, Peter (1992). The Complete 50's Masters (CD booklet notes).

- ^ Jorgensen, p.13

- ^ (August 11–August 17, 2007). "Would he still be King?". Radio Times. BBC, p.12

- ^ a b Carr and Farren, p.6

- ^ a b Hopkins 2007, p.47

- ^ Hopkins 2007, p.48

- ^ EPE (July 21, 2004). "Elvis Presley Sun Recordings". elvis.co.au. Retrieved on August 17, 2007.

- ^ a b EPE. "Elvis Presley's First Record & Early Gigs". ElvisPresley.com.au. Retrieved on 2007-10-14.

- ^ Burnett, Brown (ed.) (August 2, 2004). "Overton Park Shell 50th Anniversary, Elvis’ 1st live show". Memphis Mojo Newspaper. Reprinted in "The Buzzards". RedClock.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-14.

- ^ Naylor and Halliday, p.43

- ^ Elvis Presley Classic Albums (DVD). Eagle Eye Media, EE19007 NTSC.

- ^ Naylor and Halliday, pp.43-6

- ^ Clayton and Heard, p.69

- ^ Naylor and Halliday, p.46

- ^ Naylor and Halliday, p.52

- ^ Clayton and Heard, p.73

- ^ Guralnick 1994, p.219

- ^ Cook, p.50

- ^ Guralnick 1994

- ^ Hopkins 2007, p.53

- ^ Stanley and Coffey, p.28

- ^ Carr and Farren, p.21

- ^ Escott, p.421

- ^ Ernst Jorgensen, Elvis Presley, A Life In Music, The Complete Recording Sessions, pages 36, 54

- ^ Stanley and Coffey 1998, p.29

- ^ a b c Stanley and Coffey, p.30

- ^ a b Guralnick 1994, p.238

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (2005-02-11). "Review: Elvis Presley CD". elvis.com.au. Retrieved oo2007-10-14.

- ^ See complete Milton Berle Show Hound Dog footage with original music.

- ^ Jorgenson 1998, p.49

- ^ Raymond, Susan (Director) (1987, Re-released 2000). Elvis '56 - In the Beginning (DVD). Warner Vision.

- ^ Marino, Rick. "Elvis and Jacksonville, Florida". LadyLuckMusic.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-14.

- ^ Farren and Marchbank, p.89

- ^ Moore and Dickerson, p.175

- ^ Carr and Farren, p.12

- ^ Guralnick 1994, p.343

- ^ Stanley and Coffey, p.32

- ^ Billboard writer Arnold Shaw, cited in Denisoff, p.22.

- ^ "Elvis Presley - 1956". PBS. Retrieved on 2007-10-14.

- ^ Khurana, Simran. "Quotes About Elvis Presley". about.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-14.

- ^ Hopkins, p.126

- ^ Guralnick 1994, p.260

- ^ Harbinson, p.62

- ^ Cook, p.4

- ^ Billy Poore, Rockabilly: A Forty-Year Journey (1998), p. 20.

- ^ Guralnick, Peter (August 11, 2007). "How Did Elvis Get Turned Into a Racist?". New York Times. Retrieved on 2008-08-13

- ^ See Question of the Month: Elvis Presley and Racism Retrieved on 2007-10-14.

- ^ a b See: Kolawole, Helen (August 15, 2002). "He wasn't my king". Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved on 2007-10-14

- ^ Elder, Daniel K. "Remarkable Sergeants: Ten Vignettes of Noteworthy NCOs". ncohistory.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-13.

- ^ Guralnick 1999, p.480

- ^ Associated Press: Holiday albums can become classics fast retrieved December 22, 2007

- ^ Lichter, p.51

- ^ Clayton and Heard, p.160

- ^ Jorgensen, p.107

- ^ Guralnick 1994, p.71

- ^ "What was his rank when he got out of the army?". AllExperts. Retrieved on 2008-08-23.

- ^ Matthew-Walker 1979, p.19

- ^ a b Jorgensen, p.120

- ^ a b c d Matthew-Walker 1979, p.49

- ^ Jorgensen, p.128

- ^ Guralnick 1999, pp.89-91

- ^ Guralnick 1999, p.27

- ^ Verswijver, p.129

- ^ Hopkins 2007, p.185

- ^ Guralnick 1999, p.171

- ^ Clayton and Heard, p.226

- ^ George-Warren, Romanowski and Pareles, The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock And Roll. Excerpt in "Elvis Presley biography". Rolling Stone. Retrieved on 2007-10-14.

- ^ Kirchberg and Hendricks, p.67

- ^ Alagna, Elvis Presley

- ^ Hopkins, vii

- ^ http://archives.tcm.ie/businesspost/2002/08/18/story343531628.asp. Retrieved on 2008-07-30.

- ^ Lisanti 2000, p.9

- ^ Presley, p.188

- ^ Kirchberg and Hendricks, p. 62.

- ^ Curtin, Curtin and Ginter, p. 119.

- ^ Margret, Ann-Margret: My Story

- ^ Presley, p. 175.

- ^ Gamson, p. 46.

- ^ Harrington and Bielby, p. 273.

- ^ Stein, Ruthe (August 3, 1997). "Girls! Girls! Girls! From small-town women to movie stars". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ a b c d Kubernick, The Complete '68 Comeback Special Booklet

- ^ Binder, Steve (2005-07-08). "Interview with Steve Binder, director of Elvis' 68 Comeback Special". elvis.com.au. Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ^ Guralnick 1999, p.293

- ^ Binder, Steve (Aired: August 14, 2007). "Comeback Special". BBC Radio Two.

- ^ Moore, Scotty. 2004. A Tribute to Scotty Moore DVD

- ^ Jorgensen, p.281

- ^ a b The King on The Road, Elvis Presley Enterprises

- ^ Elvis Quotes

- ^ Stanley and Coffey, p.94

- ^ Stanley and Coffey, p.95

- ^ (Aired: August 7, 2002). "How Big Was The King? Elvis Presley's Legacy, 25 Years After His Death." CBS News.

- ^ a b Guralnick 1999, p.420

- ^ a b Guralnick 1999, in passim

- ^ Brian Roylance, The Beatles Anthology, 2000, Chronicle Books. p.192

- ^ a b c d (August 11, 2002). "Elvis Special: Doctor Feelgood". The Observer. Reprinted in Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved on 2007-10-12.

- ^ a b http://www.fiftiesweb.com/elvis-bio-70s.htm Presley Seventies Biography

- ^ Lifetime Achievement Awards Retrieved 2009-06-12

- ^ Guralnick 1999, p.490

- ^ Hopkins 2007, p.291

- ^ Elvis Presley Biography: Charitable Endeavors Retrieved 2009-06-12

- ^ a b Cause Of Death, ElvisPresleyNews.com. Retrieved on 2008-10-20.

- ^ Clayton and Heard, p.293

- ^ Jorgensen, p.381.

- ^ Roy 1985, p.131.

- ^ a b Stanley and Coffey, p.123

- ^ Roy, p.70

- ^ Garber, Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing & Cultural Anxiety (1992), p.380

- ^ Humphries, p.79

- ^ Harris, John (March 27, 2006). "Talking about Graceland". The Guardian.

- ^ Clayton and Heard, p.339

- ^ Connolly 2007, p.148

- ^ Stanley and Coffey, p.140

- ^ Hopkins 2007, p.354

- ^ Scherman, T. (August 16, 2006). "Elvis Dies". American Heritage.

- ^ a b Guralnick 1999, p.634

- ^ a b Guralnick 1999, pp.637-8

- ^ Guralnick 1999, p.174 and in passim

- ^ Guralnick 1999, p.212 and 642

- ^ Review of Medical Report. ElvisPresleyNews.com. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- ^ Patterson, Nigel (2003-01-30). David Stanley interview. Elvis Information Network (EIN). Retrieved on 2007-10-12.

- ^ Guralnick 1999, p.651

- ^ Hopkins 2007, p.386

- ^ Matthew-Walker 1979, p.26

- ^ Clayton and Heard, p.394.

- ^ Woolley, John T.; Gerhard Peters. "Jimmy Carter: Death of Elvis Presley Statement by the President". The American Presidency Project. Santa Barbara, CA:University of California (Hosted). Retrieved on 2007-10-12.

- ^ Baden and Hennessee, p.35 "Elvis had an enlarged heart for a long time. That, together with his drug habit, caused his death. But he was difficult to diagnose; it was a judgment call."

- ^ Guralnick, p.652

- ^ Clayton and Heard, p.336

- ^ Goldman, Albert, Elvis: The Last 24 Hours, p. 56

- ^ "Death of Elvis Presley Statement by the President". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- ^ Roy, p.173

- ^ a b Jorgensen, p.4

- ^ a b Cook, p.20

- ^ Sinclair, Tom (August 9, 2002). "Elvis Presley is overrated". CNN.com. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- ^ a b Associated Press (2002-08-07). How big was the king? CBS News. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ Wall, David S. (2003). "Policing Elvis: legal action and the shaping of post-mortem celebrity culture as contested space" (PDF). Entertainment Law, 2 (3): pp.35-69. doi:10.1080/1473098042000275774. Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ^ a b c d e Khurana, Simran. "Quotes about Elvis". About.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ^ "Elvis Presley biography". Music-Atlas. Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ^ Cook, p.35

- ^ Ian Gillan (2007-01-03). "Elvis Presley". Classic Rock. Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ^ "Johnny Hallyday biography". RFI Musique. Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ^ Gundle, Stephen (September 2006). "Adriano Celentano and the origins of rock and roll in Italy". Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 11 (3): pp.367-86. Royal Holloway, University of London: Routledge. doi:10.1080/13545710600806870.

- ^ Johnson, Brett (2004-06-28). "Steve Binder, Director Of Elvis' '68 Comeback Special Talks About The King". elvis.com.au. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ Cook, p.33

- ^ "Mississippi Blues Commission - Blues Trail". www.msbluestrail.org. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- ^ "Elvis gets marker on Mississippi Blues Trail - USATODAY.com". usatoday.com. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- ^ Goldman, Lea; David M. Ewalt, eds. (2007-10-29). "Top-Earning Dead Celebrities". Forbes. Retrieved on 2007-10-31.

- ^ Campos, Paul F., The Obesity Myth: Why America's Obsession with Weight is Hazardous to Your Health (2004), p.81.

- ^ Stecopoulos, p.198

- ^ (August 16, 2002). "Long Live the King". The New York Times. Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ^ (1998). "VH1: 100 Greatest Artists of Rock & Roll". VH1. Retrieved on 2007-10-16.

- ^ (2005). "CMT's 40 Greatest Men in Country Music". CMT. Retrieved on 2007-10-16.

- ^ (April 18, 2001). "Sinatra is voice of the century" BBC NEWS, Retrieved on 2007-10-16.

- ^ "Greatest American". Discovery Channel. Retrieved on 2007-10-16.

- ^ "100 Icons of the century". Variety. Retrieved on 2007-10-16.

- ^ (December 2006). "Top 100 most influential figures in American history". The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved on 2007-10-16.

- ^ (2004-04-15). "The Immortals: The First Fifty". Rolling Stone (946). Retrieved on 2007-10-16.

References[edit]

- Alagna, Magdalena (2002). Elvis Presley. Rosen Publishing Group. [[Special:Booksources/0823935248|ISBN 0823935248]].

- Austen, Jake (2005). TV-A-Go-Go: Rock on TV from American Bandstand to American Idol. Chicago Review Press. [[Special:Booksources/1556525729|ISBN 1556525729]].

- Baden, Michael M.; Judith Adler Hennessee (1992). Unnatural Death: Confessions of a Medical Examiner. New York: Random House. [[Special:Booksources/0804105995|ISBN 0804105995]].

- Bayles, Martha (1996). Hole in Our Soul: The Loss of Beauty and Meaning in American Popular Music. University of Chicago Press. [[Special:Booksources/0226039595|ISBN 0226039595]].

- Bertrand, Michael T. (2000). Race, Rock, and Elvis. University of Illinois Press. [[Special:Booksources/0252025865|ISBN 0-252-02586-5]].

- Beebe, R.; D. Fulbrook, B. Saunders (eds.) (2002). Rock over the Edge. Duke University Press. [[Special:Booksources/0822329158|ISBN 0822329158]].

- Brown, Peter Harry; Pat H. Broeske (1998). Down at the End of Lonely Street: The Life and Death of Elvis Presley. Signet. [[Special:Booksources/0451190947|ISBN 0451190947]].

- Caine, A. (2005). Interpreting Rock Movies: The Pop Film and Its Critics in Britain. Palgrave Macmillan. 0719065380.

- Carr, Roy; Mick Farren (1982). Elvis: The complete illustrated record. Eel Pie Publishing. [[Special:Booksources/0906008549|ISBN 0-906008-54-9]].

- Clayton, Rose; Dick Heard (2003). Elvis: By Those Who Knew Him Best. Virgin Publishing Limited. [[Special:Booksources/0753508354|ISBN 0-7535-0835-4]].

- Connolly, Charlie (2007). In search of Elvis. Abacus. [[Special:Booksources/9780349119007|ISBN 978-0-349-11900-7]].

- Cook, J., Henry, P. (ed.) (2004). Graceland National Historic Landmark Nomination Form (PDF). United States Department of the Interior.

- Curtin, Jim; James Curtin, Renata Ginter (1998). Elvis: Unknown Stories behind the Legend. Celebrity Books. [[Special:Booksources/1580291023|ISBN 1580291023]].

- Dickerson, James L. (2001). Colonel Tom Parker: The Curious Life of Elvis Presley's Eccentric Manager. Cooper Square Press. [[Special:Booksources/0815412673|ISBN 0815412673]].

- Denisoff, R. Serge (1975). Solid Gold: The Popular Record Industry. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Books. [[Special:Booksources/0878555862|ISBN 0878555862]].

- Dundy, Elaine (1986). Elvis and Gladys: The Genesis of the King, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. [[Special:Booksources/0708830870|ISBN 0708830870]].

- Escott, Colin. (1998). "Elvis Presley". In The Encyclopedia of Country Music. Paul Kingsbury, Editor. New York: Oxford University Press. [[Special:Booksources/0195176081|ISBN 0195176081]].

- Falk, Ursula A.; Gerhard Falk (2005). Youth Culture and the Generation Gap. Algora Publishing. [[Special:Booksources/0875863671|ISBN 0875863671]].

- Farren, Mick; Pearce Marchbank (1977). Elvis In His Own Words. New York: Omnibus Press. [[Special:Booksources/0860014878|ISBN 0860014878]].

- Finstad, Suzanne (1997). Child Bride: The Untold Story of Priscilla Beaulieu Presley. New York: Harmony Books. [[Special:Booksources/0517705850|ISBN 0517705850]].

- Gamson, Joshua (1994). Claims to Fame: Celebrity in Contemporary America. University of California Press. [[Special:Booksources/0520083520|ISBN 0520083520]].

- George-Warren, Holly; Patricia Romanowski, Jon Pareles (2001). The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock And Roll. Fireside. [[Special:Booksources/0743201205|ISBN 0-7432-0120-5]].

- Goldman, Albert (1990). Elvis: The Last 24 Hours. St Martins. [[Special:Booksources/0312925417|ISBN 0312925417]].

- Guralnick, Peter (1994). Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. [[Special:Booksources/0316332259|ISBN 0316332259]].

- Guralnick, Peter (1999). Careless Love. The Unmaking of Elvis Presley. Back Bay Books. [[Special:Booksources/0316332976|ISBN 0316332976]].

- Harbinson, W. A., (1977). The life and death of Elvis Presley. London: Michael Joseph. [[Special:Booksources/0517246708|ISBN 0517246708]].

- Harrington C. Lee; Denise D. Bielby (2000). Popular Culture: Production and Consumption. Blackwell. [[Special:Booksources/063121710X|ISBN 063121710X]].

- Hopkins, Jerry (2002). Elvis in Hawaii. Bess Press. [[Special:Booksources/1573061425|ISBN 1573061425]].

- Hopkins, Jerry (2007). Elvis. The Biography. Plexus. [[Special:Booksources/?|ISBN 0859653919]].

- Humphries, Patrick (2003). Elvis The #1 Hits: The Secret History of the Classics. Andrews McMeel. [[Special:Booksources/0740738038|ISBN 0740738038]].

- Jorgensen, Ernst (1998). Elvis Presley: A life in music. The complete recording sessions. St. Martin's Press. [[Special:Booksources/0312185723|ISBN 0312185723]].

- Kirchberg, Connie; Marc Hendricks (1999). Elvis Presley, Richard Nixon, and the American Dream, Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company. [[Special:Booksources/0786407166|ISBN 0786407166]].

- Lichter, Paul (1980). Elvis - The Boy Who Dared To Rock. Sphere Books. [[Special:Booksources/0722155476|ISBN 0 7221 5547-6]].

- Lipton, Peggy; Coco Dalton, David Dalton (2005). Breathing Out. St. Martin's Press. [[Special:Booksources/0312324138|ISBN 0312324138]].

- Lisanti, Tom (2000). Fantasy Femmes of 60's Cinema: Interviews with 20 Actresses from Biker, Beach, and Elvis Movies. McFarland and Company. [[Special:Booksources/0786408685|ISBN 0786408685]].

- Lisanti, Tom (2003). Drive-In Dream Girls: A Galaxy of B-Movie Starlets of the Sixties. McFarland. [[Special:Booksources/0786415754|ISBN 0786415754]].

- Margret, Ann; Todd Gold (1994). Ann-Margret: My Story. G.P. Putnam's Sons. [[Special:Booksources/0399138919|ISBN 0399138919]].

- Matthew-Walker, Robert (1979). Elvis Presley. A Study in Music. Tunbridge Wells: Midas Books. [[Special:Booksources/0859361624|ISBN 0859361624]].

- Miller, James (1999). Flowers in the Dustbin: The Rise of Rock and Roll, 1947–1977. Fireside. [[Special:Booksources/0684865602|ISBN 0684865602]].

- Moore, Scotty; James Dickerson (1997). That’s Alright, Elvis. Schirmer Books. [[Special:Booksources/0028645995|ISBN 0028645995]].

- Nash, A.; M. Lacker, L. Fike, B. Smith (1995). Elvis Aron Presley: Revelations from the Memphis Mafia. Harper Collins. [[Special:Booksources/006109336X|ISBN 006109336X]].

- Naylor, Jerry and Steve Halliday (2007). The Rockabilly Legends; They Called It Rockabilly Long Before they Called It Rock and Roll (Book and DVD). Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation. [[Special:Booksources/142342042X|ISBN 142342042X]].

- Pratt, Linda R. (1979). "Elvis, or the Ironies of a Southern Identity". Elvis: Images and Fancies. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- Presley, Priscilla, (1985). Elvis and Me. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. [[Special:Booksources/0399129847|ISBN 0-399-12984-7]].

- Rodman, G., (1996). Elvis After Elvis, The Posthumous Career of a Living Legend. London: Routledge. [[Special:Booksources/0415110025|ISBN 0415110025]].

- Rodriguez, R., (2006). The 1950s' Most Wanted: The Top 10 Book of Rock & Roll Rebels, Cold War Crises, and All-American Oddities. Potomac Books. [[Special:Booksources/1574887157|ISBN 1574887157]].

- Roy, Samuel (1985). Elvis: Prophet of Power. Branden Publishing Co. Inc. [[Special:Booksources/0828318980|ISBN 0-8283-1898-0]].

- Shepherd, Cybill; Aimee Lee Ball (2000). Cybill Disobedience. Thorndike Press. [[Special:Booksources/0061030147|ISBN 0061030147]].

- Stanley, David E.; Frank Coffey (1998). The Elvis Encyclopedia. London: Virgin Books. [[Special:Booksources/0753502933|ISBN 0753502933]].

- Stecopoulos, H.; M. Uebel (1997). Race and the Subject of Masculinities. Duke University Press. [[Special:Booksources/0822319667|ISBN 0822319667]].

- David Szatmary (1996). A Time to Rock: A Social History of Rock 'n' Roll. New York: Schirmer Books. [[Special:Booksources/0028646703|ISBN 0028646703]].

- Verswijver, L., (2002). Movies Were Always Magical: Interviews with 19 Actors, Directors, and Producers from the Hollywood of the 1930s through the 1950s. McFarland & Company. [[Special:Booksources/0786411295|ISBN 0786411295]].

- Walser, Robert; David Nicholls (ed.) (1999). The Cambridge History of American Music. Cambridge University Press. [[Special:Booksources/0521454298|ISBN 0521454298]].

- West, Red; Sonny West, Dave Hebler (As Told To Steve Dunleavy) (1977). Elvis: What Happened. Bantam Books. [[Special:Booksources/0345272153|ISBN 0345272153]].

Further reading[edit]

- Goldman, Albert (1981). Elvis. McGraw-Hill. [[Special:Booksources/0070236577|ISBN 0-07-023657-7]].

- Allen, Lew (2007). Elvis & the birth of rock. Genesis Publications. [[Special:Booksources/1905662009|ISBN 1-905662-00-9]].

- Cantor, Louis (2005). Dewey and Elvis - The Life and Times of a Rock 'n' Roll Deejay. University of Illinois Press. [[Special:Booksources/025202951x|ISBN 0-252-02981-X]].

- Chadwick, Vernon (ed.) (1997). In Search of Elvis: Music, Race, Art, Religion. Proceedings of the first annual International Conference on Elvis Presley, Westview. ISNB 0813329876.

- Doss, Erika Lee (1999). Elvis Culture: Fans, Faith, and Image. University of Kansas Press. [[Special:Booksources/0700609482|ISBN 0700609482]].

- Hopkins, Jerry (2007). Elvis. The Biography. Plexus. [[Special:Booksources/?|ISBN 0859653919]].

- Marcus, Greil (1991). Dead Elvis: A Chronicle of a Cultural Obsession.

- Marcus, Greil (2000). Double Trouble: Bill Clinton and Elvis Presley in a Land of No Alternative. [[Special:Booksources/057120676X|ISBN 057120676X]].

- Nash, Alanna (1995). Elvis Aaron Presley: Revelations from the Memphis Mafia. Harper Collins. [[Special:Booksources/006109336X|ISBN 006109336X]].

- Nash, Alanna (2003). The Colonel: The Extraordinary Story of Colonel Tom Parker and Elvis Presley. Simon and Schuster. [[Special:Booksources/0743213017|ISBN 0743213017]].

- Tamerius, Steve D. & Worth, Fred L. (1990). Elvis: His Life From A to Z. Contemporary Books. ISBN 0809245280.

External links[edit]

- Elvis Presley at IMDb

- Rikstar/Sandbox at AllMovie

- Rikstar/Sandbox at Find a Grave

- Elvis Presley Enterprises - Official site of the Elvis Presley brand.