User:Resident Mario/Rum

Rum, a distilled beverage made from sugarcane by-products such as molasses and sugarcane juice, has had a long history ever since its conception sometime in the early 16th century. The exact origin of the beverage is unclear, stemming back into ancient times, but it's modern version is believed to have originated on the island of Barbados. There, it was brewed by sugar planters looking to find a use for molasses, a sticky tar of no economic value that originates from the sugar distilling process. Rum was born when planters realize that by fermenting molasses, they could make a remarkably strong alcloholc beverage.

Although rum initially stayed primarily in the British island colonies, it quickly spread to the American colonies via traingle trade. There it displaced hard cider as the beverage of choice, and became the most popular alcloholic beverage of its time. As trade extended towards Great Britian, rum came in contact with pirates, who took a liking to the powerful beverage; it is during the Golden Age of Piracy that rum would become associated with piracy. Rum also played a role with the British navy sailors, who recieved two "tots" (pints) of rum per day, and with early American traders, who found they could trade rum to the Indians to great advantage. Rum was immensly popular in North America, playing an intricate role in the conflicts leading up to and during the Revolutionary War.

Following the Revolutionary War, rum went into decline. Changing tastes and an increasing shortage of molasses led to its deep decline that lasted all the way through Prohibition.

Origins[edit]

The precursors to rum date back to antiquity. Development of fermented drinks produced from sugarcane juice is believed to have first occurred either in ancient India or China,[1] and spread from there. An example of such an early drink is brum. Produced by the Malay people, brum dates back thousands of years.[2] Marco Polo also recorded a 14th-century account of a "very good wine of sugar" that was offered to him in what is modern-day Iran.[1]

The exact origin of the modern version of rum is unclear. What is today known as rum was most likely first brewed from sugarcane on the British island colony of Barbados. However, it may have had its origins in the Spanish colony of Hispaniola (modern day Dominican Republic), or possibly by the French in one of their Caribbean island colonies, where poorer grades of rum are called tafia. Beverage expert Edward Hamilton has argued that rum was first brewed commercially in the Portuguese colonies, and has been looking for commercial records to prove it (however, it is unlikely they exist, as rum exports from Spanish and Portuguese colonial settlements were prohibited and were mostly smuggled, for which no or little records exist).[3] Even more theoretically, it may have first been concocted among the tinkering of Middle Ages alchemists seeking the exiler of life; to these early chemists, alcohol was a divine substance, neither liquid nor solid, as it evaporated quickly on contact with air, and was thus often central to many of their experiments. It may even have first been distilled even earlier in history, in a sugarcane field of India.[3] Compared to the overflowing record regarding sugar, from whose by-products rum is retrieved, the early history of rum is extremely sketchy.[3]

The first definite distillation of rum took place on the sugarcane plantations of the Caribbean in the 17th century. Plantation slaves first discovered that molasses, a by-product of the sugar refining process, can be fermented into alcohol.[4] Later, distillation of these alcoholic by-products concentrated the alcohol and removed impurities, producing the first true rums. Tradition strongly suggests that rum first originated on the island of Barbados. The first record of rum comes from the diary of sea captain John Josselyn, who wrote of as dinner party held on a ship off the coast of Maine (then part of Rum Rebellion) in September of 1639, during which another captain toasted him "a pint of rum."[3] Both the word rum and kill-devil (the slang term for the harsh rum of that day) originated from the Barbados.[5]

Laws attempting to control the sale of rum popped up soon after in several different colonies- in Bermuda in 1653, in Connecticut in 1654, and in Massachusetts in 1657. These laws were systematically ignored; the later forceful attempts to make the colonies obey them would contribute to rebellions like the Rum Rebellion and the American Revolution. The earliest source in which rum played a prominent role was in the midst of a extravaganza party thrown by the prominent Barbados planter James Drax, sometime before 1640. During the 1650s, the drink would expand greatly in popularity.[3] The first official record using the word "rum" comes from a 1658 deed for the sale of Three Houses Plantation, which alludes to "four large mastrick cisterns for liquors of rum" (laws governing liquor had previously been passed that referred to "this country's spirits")[5]

Early history in the Caribbean[edit]

Regardless of its initial source, early Caribbean rums, collectively referred to as kill-devil, were not known for high quality. A 1651 document from Barbados stated, "The chief fuddling they make in the island is Rumbullion, alias Kill-Divil, and this is made of sugar canes distilled, a hot, hellish, and terrible liquor".[4][3] The island of Barbados was at the time the biggest sugar producer in the world. The arrival of new beverages to England, including coffee (in 1650), chocolate (1657), and tea (1660) greatly spiced the demand for sugar. Barbados colonists initially tried to grow cotton, indigo, fustic wood, and a type of mulberry that produces a yellow dye. Taking a cue from the Virginian colonies, the islanders then tried to grow tobacco, which turned out "earthy and worthless," as one visitor called it. Then Barbados tried out sugar, and landed in the middle of the greatest sugar boom in history. Between 1660 to 1700, the per capita consumption of sugar for British citizens more than quadrupled. Soon, the whole island was colonized extensively- the population of the island swelled from just 80 in 1627 (the time of the first colonization) to more then 75,000 by 1650.[6]

The by-product of the sugar curing process was molasses, a sticky, black, caramelized tar of no great economic value that resisted crystallization or further refining. The amount of "waste" produced was considerable; wheras the amount varied, the typical figure was one pound of molasses for every two pounds of sugar. With heavy refining, the ratio might become as high as three pounds of molasses for every four of sugar.[7]

In the mid-seventeenth century, molasses was a nuisance; too bulky to ship economically, and there was little or no demand for it anyway. Some would be mixed with grain and fodder to be fed to the cows, and some would be fed to the slaves to supplement their meager diet. Molasses could be mixed with lime, water, and horsehair to make a crude mortar, and blended with various nostrums as a cure for syphilis. But the majority of the compound was simply disposed of in a manner similar to that of industrial waste. One traveler noted that it was "never esteemed for more then dung; for they used to throw it all away."[7] At some point it was realized that there was enough sugar in the compound to attract the attention of yeast, which separates sugar into (partially) alcohol. By distilling the molasses, farmers realized that they could produce an alcoholic drink-rum.[7]

Early brewers generally followed a methodology. They would pour, into a large cistern, a messy black fluid composed of molasses, the dregs remaining from the previous batch, and water (used to clean the pots between batches). This mixture, called wash, was left to stand in the tropical heat. Because the molasses is contaminated with yeast, it begins to ferment, and the yeast splits the sugar in the molasses into carbon dioxide and alcohol. The temperature of the mixture was closely monitored; windows in the still room would be opened and closed to regulate the temperature. If the temperature rose to a near-blood hot level (near 37° Celsius), pails of cold water were added to cool it down; if it grew too cold, hot sea sand was added to heat the mixture up.[8] In addition the brewers controlled the acidity; if it was not acidic enough, they would add lemons, tartar, or tamarinds. If it was too acidic, live coals or wood ash helped. Sometimes animal carcasses or dung was added, to kickstart a batch that resisted fermentation.[8] Other substrates could be added to the batch, but for other reasons. An early traveler to Jamaica, noted:

"Perhaps the overseer will empty his chamberpot into it... to keep the Negroes from Drinking it." —John Taylor[8]

Once the temperature of the wash fell and bubbling stopped after a few days, the mildly alcoholic brew was ready for distillation. The wash was conveyed, via small taps at the bottom of the cistern (taps were preferred as they filtered out any sediment), to a pot still. A low, even fire was applied to the main vat of the still, and the steam generated would rise and progress through a bit of copper tubing called a worm. The worm had to be constantly protected from overheating; the best way to do this was to divert cold water into the vat. However, in water-scarce areas like the Barbados, the cooling was done with water cooled in a nearby yard by slaves with pails, and later by wind-powered pumps.[8]

The spirit produced, kill-devil, could be drunk at first distillation or run through the still a second or even third time. Barbadians preferred spirits of a single extraction, and usually had theirs casked after a single pass, resulting in what one traveler called "a cooler spirit, more palatable and wholesome."[8] Other islands, like Jamacia (which would overtake Barbados in rum production in the mid-nineteenth century) preferred a strong, double-distilled rum. Samual Martin noted that the Jamacian approach:

"...seems more profitable for the London-market, because buyers there approve of a fiery spirit which will bear most adulteration." —Samual Martin[8]

However, for a time the popularity of rum remained mostly limited to the island colonies. By 1655, an estimated 900,000 gallons of kill-devil per year was being produced on Barbados, yet virtually no export market existed. Small amount have been recorded to as early as 1638, but as late as 1698, a mere 207 gallons of rum were officially exported to England from Barbados (this figure is likely low due to smuggling). Almost all of the spirits produced were consumed right on the island, by the local residents; in Barbados, the per capita consumption rate was on the order of 10 gallons a day.[9]

Early rum makers found a market in the many poor among the islands. On Barbados, for example, 94% of those setting off from England for the island in 1635 were men, young and poor. While gentry lived fabulously, most of the islanders lived rough lives. In 1631, Henry Whistler described Barbados as

"...the dunghill whereon England doth cast forth its rubbish. Rouges and whores and such like people are those which are generally brought here. A rouge in England would hardly make a cheater here." —Henry Whistler[9]

Disappointment was common among the new arrivals. Whereas they had heard of fabulous land from which to grow great riches in England, in reality most of the land had already been snapped up by larger landowners. Indentured servants likewise found the promise of "upward mobility" uttered in London to be overblown at best. Jobs were scarce; landowners found it easier to ship slaves onto the island, who could perform the same tasks more economically then their white counterparts, as well as being more resistant to tropical disease.[9]

Rum proved to be a cheap and economical outlet for the chronically disappointed settlers. Tippling houses, as the drinking taverns were often called, were as widespread as they were economical; at the time Bridgetown had one tippling house for every twenty residents. Rum emerged as a social and economic issue when many of the islands tried to license them. It was not uncommon for men used to drinking two to three drams daily to start drowning thirty to sixty once on the islands. The residents of the colonies were generally and universally described as "great drunkards." One traveler described how they "buy their drink although they goe naked." Rum later became an important part of triangle trade, with livestock and produce sailing south to the islands (where every acre of land was devoted to sugar or other cash crops), and rum in turn sailing to the north.[10]

Colonial America[edit]

"rum, alias Kill Devil, is much ador'd by the American English... This is held as the Conforter of their Souls, the Preserver of their Bodys, the Remover of their Cares, the Preserver of their Bodies, and Promoter of their Mirth; and is a Sovereign Remedy against the Grumbling of the Guts, a Kibe-heel [chilblians on the heel], or a Wounded Conscience, which are the three Epidemical Distempers that afflict the Country."

— British author Edward Ward, 1699.[10]

After rum's development in the Caribbean, the drink's popularity spread to Colonial America once the island production outsourced the local demand.[10] To support the demand for the drink, the first rum distillery in the colonies was set up in 1664 on present-day Staten Island. Boston, Massachusetts had a distillery three years later.[11] Soon, British North America became what some historians call "the Nation of Rum."

The manufacture of rum became early Colonial New England's largest and most prosperous industry.[12] Early strong spirits had been recorded as far back as 1630; a crude whiskey was first produced by an enterprising Dutchman near Manhattan in 1640.[13] Starting in the early 1700s, the colonial taste for home-brewed beer and cider started to dry up, to be replaced by a love for rum.[14] This was spurred partially by the cheapness of it, as well as the abundance. The cost of a fifth of a gallon of rum dropped by a third between 1673 and 1687 before leveling off at four dollars, about half the price of a bottle of cheap rum today. One resident marveled how it cost "but a penny or two" to get drunk on imported rum.[13]

Rum soon found its way into many aspects of colonial life; it was common to down a dram at first light, during dinner, at midday, and in the evening. However, it wasn't just a pastime, as it also served as a vital supplement to their diet, as it has about as many calories per ounce as butter and ten times that of milk. In addition rum was used as a cure-all, with a dram often being the first thing for a sign of sickness. Leaves of the tansy plant dipped in rum were a popular cure-all of the time. There were even first-aid implementations in place that called for the splashing of hot rum on a collapsed man's chest while smoking tobacco in the hopes of reviving him. Swedish traveller Peter Kalm noted that that by 1750 rum had come to be considered far healthier then spirits disttilled from grain or wine.[13]

New England became a distilling center (due to the superior technical, metalworking and cooperage skills and abundant lumber); the rum produced there was lighter, more like whiskey, and was superior to the character and aroma of the West Indies product. Anyone who could afford it much preferred it to the more expensive Caribbean product.[13] Rhode Island rum even joined gold as an accepted currency in Europe for a period of time.[15] Estimates of rum consumption in the American colonies before the American Revolutionary War had every man, woman, or child drinking an average of 3 Imperial gallons (13.5 liters) of rum each year.[16] The rums went by many names, but among the most popular was a variant called flip, a mixture of beer, molasses, and Jamaican rum.[14] As Boston and other cities grew, and land there became more expensive, industries migrated to areas where there were cheaper tracts of land. The town of Newport would absorb much of Boston’s rum business in particular.[13]

Reports of early rum distilleries surface about 1684, but it was not until the beggining of the eighteenth century that the domestic industry really kicked off. The rapidly advancing rum market was aided in part by brewers from England, who migrated as the British government began to restrict the brewing industry, and by indentured servents displaced from the Carribean, pushed out by the scarce remaining land and a shallow demand for labor due to slave labor. The industry rapidly accelerated; if one was talking about rum in America prior to 1700, he most likely meant imported Caribbean rum, wheras into the eighteenth century he was most likely refering to domestically produced rum. Boston was at the forefront of the industry, going from importing 156,000 to producing over 200,000 gallons of rum in a span of just under thirty years. Close behind were Rhode Island, New York, and Philadelphia. In 1763, New England had approximately 163 operating facilities. Of the 6.5 million imported gallons of molasses, 5 million were distilled into rum.[17]

To support this demand for the molasses to produce rum, along with the increasing demand for sugar in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries, a labor source to work the sugar plantations in the Caribbean was needed. A triangular trade was established between Africa, the Caribbean, and the colonies to help support this need.[18] The exchange of slaves, molasses, and rum was quite profitable, and the disruption to the trade caused by the Sugar Act in 1764 may have even helped cause the American Revolution.[16]

The popularity of rum continued after the American Revolution with George Washington insisting on a barrel of Barbados rum at his 1789 inauguration.[19] In one publication of the Pennsylvania Gazette, Benjamin Franklin printed 228 words that were slang for drunk. Among them were "cock'd," "juicy," "fuzl'd," "stiff," "wamble crop'd," "crump footed," "staggerish," and perhaps the most notable:"Been to Barbados."[10]

Rum soon started to become an important aspect in the political system. The outcome of the election usually depended on the candidate’s generosity with rum. The people would vote for incompetent candidates only because they provided more rum. They would attend the election to see which candidate appeared less stingy with their rum. The candidate was expected to drink with the people to show that he was independent and truly a republican. In a Mississippi election, one candidate poured his drinks and socialized with the people. He was more personal and it appeared as if he was going to win. The other candidate announced that he would not be pouring their drinks and they could have as much as they wanted; because he appeared more generous, he won. This shows that colonial voters weren’t concerned with what the candidate represented or stood for; they were merely looking for who would provide the most rum.[20]

Use in trade with Native Americans[edit]

"[the Indians] claim'd and receiv'd the rum; this was in the afternoon; they were near one hundred men, women, and children, and were lodg'd in temporary cabins, built in the form of a square, just without the town. In the evening, hearing a great noise among them, the commissioners walk'd out to see what was the matter. We found that they had made a great bonfire in the middle of the square; they were all drunk, men and women, quarreling and fighting. Their dark-colour'd bodies, half naked, seen only by the gloomy light of the bonfire, running after and beating one another with firebands, accompanied by horrid yellings, form'd a scene the most resembling our ideas of hell that could well be imagin'd; there was no appeasing the tumult, and we retired to our lodgings. At midnight a number of them came thundering to our door, demanding more rum, of which we took no notice."

— Benjamin Franklin, in his autobigraphy [21]

Early colonists discovered rum to be exceptionally useful for trading with the Indians. As the dink spread inland, colonists would buy a stock of rum, wheel it inland to a remote fort or trading post, and then trade it to the Indians to great advantage. The first settlers had found many faults in the manner, appearance, and habits of the "natives" when they first landed, but the quality that irked them the most was the natives' stubborn resistance to becoming consumers. The eastern woodland Indians didn't have excessive needs, and grew or made everything they needed. At the same time, they were skillful hunters, able to amass large stocks of the beaver and mink furs which the colonial traders coveted. At first, the Native Americans were willing to trade furs for small trinkets like glass beads and woven blankets, combs, and glass; however, this evidently wore of quickly, and traders needed a new tradable item, something that was cheap and easy to get, yet provided its own demand.[21]

Rum would turn out to be just what the colonists needed. It was easy to obtain, affordable, and provided a large profit. At best, cookware and trinkets could be traded for double their worth; but rum was easily traded for quadruple its value. An even bigger profit could be made by watering it down-a keg of rum could be watered down by a third without a fuss. It proved so valuable a commodity that for years rum cost more in New York City, a major base for fur traders going up the Hudson, then it did in comeparable cities like Boston.[21]

The drink proved to be an extremely valuable weapon in negociations, as well. A glass of rum often opened negotiations between settlers and Indians as a sign of friendship, and was used to seal the deal therafter. Rum was distributed during buisness, sometimes simply because the Native Americans asked for it. Traders boasted of how they could compromise local's trading power. For their part, the Native Americans grew wary of the beverage, but the traders proved adept at bringing rum into the negotiations.[21]

"Little Turtle petitioned me to prohibit rum to be sold to his nation for very good reason. He said, I had lost three thousand of my Indian children in his nation in one year by it. Sermons, moral discourses, philanthropic dissertations, are all lost on the subject. Nothing but making the commodity scarce and dear will have any effect. But [...] critics would say that I was a canting Puritan, a profound hypocrite, setting up standards of morality, economy, temperance, simplicity, and sobriety that I knew the age was incapable of."

— President John Adams, in a letter to a friend describing his difficult situation; eventually, he would do nothing. [21]

However, rum had a profound affect on the Native Americans, who had never been exposed to such strong drink before. Intoxicated Indians were refered to variously as "mad bears" and "many raging devils." In his 1775 journal on Ohio and Indiana, Nicholas Cresswell wrote that the Native Americans he'd encountered were "inclined much to silence, except when liquor which they are very fond of, and then they are very loquacious commiting the greatest outrages upon one another."[21]

Some colonists could not ignore the effect of rum on the Indians, and demanded prohabations be placed on its trade and sale. This was less altruism then self-defense, for rum-sodden Indians were thought to be more likely to attack settlements then sober ones. Likewise, the tribes themselves pushed to ban the liquid. In 1768, Shawnee cheif Benewisco said that "Rum is the thing that makes us Indians poor & foolish." Efforts to curb the trade started early-trading liquor with Indians was made illegal in Massachusetts in the 1630s, in the New Hampshire in the 1640s, in Rhode Island in 1654, and in Pennsylvania in the 1680s. However, all of the laws were either revoked, watered down, or simply ignored. The Indian nations would continue to weaken, partially, as a result of it, and eventually collapse.[21]

Role in the Revolutionary War[edit]

Conflict[edit]

"I know not why we sould blush to confess that molasses was an essential ingrediant in American independance. Many great events have proceeded from much smaller causes.

— President John Adams[22]

Most of the molasses used in American rums came from the French West Indies, for a single reason—it was astoundingly cheap. Although they started later then the British, the French made up for it by expanding at an astounding clip—by the time of the American Revolution, Haiti alone produced more sugar then all of the British islands combined. In addition, the French had virtually no home market for the excess molasses, as French distillers had blocked the export of molasses and rum, fearing for the suffering of their wine and brandy industries. As a result French molasses was practically free for the taking. Although the exact export numbers are unknown, it is known that in 1688 Boston imported 156,000 gallons of rum, but by 1716, as the rum industry boomed, the figure dropped by over half to 72,000—a gap surely made up by the French. It was a similar situation elsewhere; a New Yorker once remarked that the distilleries in New York City were "wholly supplied with molasses from Martinique."[23]

This mutual trade with the French, Britain’s mortal enemy for centuries, greatly angered the British sugar merchants. Merchants watched as their molasses market dried up. Angry British farmers and merchants turned to the British Parliament to remedy the situation. The general theory for colonization at the time was that the colony operated for the benefit of its mother country, and they argued, what did Britain gain from this trade? The simple answer was nothing.[23]

At first they suggested a weapon that was far too blunt—the outright banning of all trade with the French. This failed, so instead the Parliament agreed on heavy tariffs to be placed on French sugar products bound for America, in what was known as the Molasses Act of 1733.[23]

Under heavy tariffs, British molasses now cost less then the French-made equivalent. Parliament had, in effect, sacrificed half a million northern colonists to appease about 50,000 influential British islanders. Northern residents, faced with a choice of following the act or ignoring it, chose the latter path—in 1735, just two years after the act was passed, parliament collected just 2 pounds of officially imported foreign molasses. Altogether the crown collected just 13,702 pounds from tariffs on foreign sugar products. For a brief period at the end of the Seven Years War, Britain held several French isles, and it seemed as if distillers could finally avoid the hassle of smuggling. However, under generous terms, the islands were returned and Britain took Canada instead, generally seen as a lesser prize.[23]

The Seven Years War was a long and pricey affair, greatly draining the British Treasury. Seeing the America had most to benefit from the victory (which secured their flank and allowed unhindered expansion south and west), Parliament decided to refill their coffers via taxation. Discarding the ineffective Molasses Act, Britain instead reinstated the Sugar Act. Whereas its predecessor was an attempt to restrict trade, the new act was created chiefly to raise revenue. Whilst the tariffs were actually lowered, from 6 to 3 cents, in return the British upheld it with uncommon zeal; the navy was ordered to pursue offenders on the high seas, 27 ships were divvied out for the role, and officers who failed to be strict enough in their prosecutions were abruptly dismissed. Some companies actually followed the law; the majority bumped along as well as they could, absorbing high expenses and the added burden on smuggling. The act was generally seen as an injustice to Colonial America. Eventually, against all odds, distillers persuaded Parliament into this. In 1766 the Sugar Act was revised, and the tariff was dropped down to one cent per gallon, so low that the hassle of smuggling was actually more expensive then following the law.[23][24]

England feared that the colonial success in rolling back the Sugar Act would be viewed as a wholesale victory for the colonists and emboldem them further. the resistance to the act marked the first time all of the colonies had bonded togethor to resist against British rule. So, to reinstate their power, they passed the despised tea act, and then the even more despised Stamp Act, that year. The new acts put taxes on all forms of paper, from liquor liscenses to candy wrappers to alamanacs, as well as imported tea. and so was born "No taxation without representation," and the colonies would soon after rebel against their rulers, starting the Revolutionary War.[24]

War[edit]

Distillers and rum merchents played a paramount role in the uprising, and unsuprisingly so; taverns and pub houses were community conglomerates, virtual "petri dishes" for the brewing of the discontent seen in the American colonists. In addition they had already been maimed by the British Sugar and Molasses Acts, and were already generally discontent with British rule. For example, of the 90 liscensed tavernkeepers in Boston, 20 were members of the Sons of Liberty, the group behind the Boston Tea Party. Historian David Conroy noted that "the manufactures and importers of the most contreversial commodity in the providence and the colonial world stood at the very helm of the resistance movement."[24]

In backing the rebellions, tavern-keepers and, even more so, the distillers risked their livelihood. During the war the British navy blockaded all American ports, so importing goods was extremely difficult–unless you had connections with the British, who continued to import material from the British-held ports, including New York City. As a result, the amount of imported West Indies rum and molasses dwindled, resulting in the likewise decline of rum production.[25]

This was a great loss to the Continental Army; rum had long been used as a form of currency in the country, and its disappearance made it even harder for the money-strapped Continental Congress to raise funds. In one example of rum’s role in the American Revolution, the New Hampshire politician John Langdon donated some 150 hogsheads of rum the state to help raise the Continental militia. The drink also had applications on the more practical level, as a provision for war. Following the example set by the British navy, the Continental Navy orders for the distribution of "a halfpint of rum per man every day."[25]

As the grueling 6-year war continued, rum became increasing hard to come by, to the great dismay of the American soldiers. In a letter to the Continental Congress pleading for supplies, George Washington wrote that "beer or cyder seldom comes within the verge of the camp, and rum in much too small quantities." The drnk even haad small effects on the battlefield; at the Battle of Eutaw Springs, charging colonial troops forced the British out of their camp, leaving their breakfasts uneaten. The hungry militia foun great quantities of rum and food, and wasted no time in availing both. The British merly waited for the rum and food to take effect, and then drove them back into the forest in disarray.[26]

[edit]

Association with pirates[edit]

Rum's association with piracy began with English privateers trading on the valuable commodity. As some of the privateers became pirates and buccaneers, their fondness for rum remained, the association between the two only being strengthened by literary works such as Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island.[27]

The association of rum with pirates began with the merchent ships which the pirates raided. Once it outgrew its origins, rum became a valuable commodity for trade, and played a prominent role in the triangle trade that dominated the region, with livestock and produce sailing south and rum and slaves sailing north. The trade steadily grew during from the 1660s onward, with Barbados and Antigua being the most common destinations because of how easily rum is obtained there. More then 90 percent of the rum exported from the two islands went to the British American colonies, and in some colonies it topped 100 percent; Europe had not yet become a signifigant market at the time. Export figures from 1726 to 1730 show that the most important rum exporter was Barbados, which shipped 680,269 gallons of rum; this was followed by Antigua with 235,966 gallons, and then St. Kittes and Montserrat, which togethor shipped about 14,000 gallons of rum.[10]

At first, early pirates and privateers concentrated on the already well-established Spanish Empire. As Spain's empire collapsed, the pirates gradually turned their attention to the British territories. Now hunting the British merchent ships, pirates came into contact with Caribbean rum, which they took an extreme liking too. As the eighteenth century progressed, rum would displace wine in accounts of pirate debauchery—and would come to be associated with disorder and mayhem on the seas.[10] Men captured by pirates spoke almost unconditionally of their bad habits, among them, lofty drinking:

"...I soon found that any death was perferable to being linked with such a vile crew of miscreants. Monstrous cursing and swearing, hideos blasphemies, and open defiance of Heaven appall me deeply, as does another habit—prodigious drinking."

- —Phillip Ashton, a ship's captain captured by pirates en route from Barbados to Boston in 1724.[10]

"They passed their idle time boasting, then drinking and carousing merrily, both before and after dinner, which they ate in a very disorderly manner, more like a kennel of hounds, then like men, snatching and catching the victuals from one another."

- —Captain George Roberts of London, during his period of captivity to the infamous pirate Ned Low.[10]

"They captured so much liquor that it was esteemed a crime against Providence not to continually drink."

- —An observer commenting on Bartholomew Roberts's massive haul of rum from raids in 1720.[10]

However, pirtate life wasn't all anarchy, however; upon joining, crewmembers often had to sign charters, mini constitutions that governed their conduct on the ship and the division of the spoils. Rum played a prominent role in the charters, and often they codified the distribution of liquor. For example, the charter of Bartholomew Roberts, better known as "Black Bart," stated that every man "has an equal title to fresh provisions or strong liquores at any time seized, and may use them at pleasure unless a scarcity make it necessary for the food of all to vote a retrechchment." Two of his crewmen were particularly famous; Robert Devins was always drunk and scarcly fit for duty, as reported at his trial after capture, and at one point Robert Johnson became so thoroughly engrossed that he had to be removed from the ship with block and tackle.[10]

Easily the most legendary lover of drink was undoubtly the most famous pirate of them all, Edward Teach—better known as Blackbeard. He and his crew would make stops on islands between harrasing ships to indulge in collosal amounts of drink. One biographer, Robert Lee, wrote that "Rum was never his master. He could handle it as no other man of his day, and was never known to pass out from excess."[28]

The de facto capital of piracy was Port Royal, the cheif port of Jamacia. Before the island would become a sugar powerhouse, Jamacia's economy was based mostly on trade, a large percentage of it illegal. The port made an extremely appealing base to pirates, particularly because local governers cast a blind eye on it;to them, pirates were a useful nuisance. They brought in gold and silver to bouy the local economy—so much so that the notion of establishing a British mint there was considered in 1662—and served as an ad hoc naval defense force at no cost to the governer. With its abundance of caputured gold, Jamacia was a tasty target to French and Spanish marauders, but a harbor teeming with pirate ships and their crew greatly reduced the chance of such an action.[28]

Port Royal, ungoverned from the start, soon became ungovernable. After raids, pirates would often return to Port Poyal to whore and drink and spend their loot as they pleased. Pirates were not usually very good with money, and parted with their gold—dumping it into the local economy—at an astounding rate. Curchman and pirate chronicler Charles Leslie once wrote that:

"Wine and Women drained their Wealth to such a Degree that in little time some of them became reduced to Beggary. They have been known to spend 2 or 3000 Peices of Eight in one Night; and one of them gave a Strumpet 500 to see her naked." —Charles Leslie[28]

The priveteer Henry Morgan noted then pester him to set off on further raids, "therby to get something to expend anew in wine and strumpets."

Port Royal also housed a density of tippling houses that made the stock in Barbados look meak. Even discounting unliscensed and undocumented rumshops—of which there were surely many—Port Royal had a tavern for every ten male residents. A visitor wrote in a 1664 letter that all of the "servents and inferior kind of people," which was surely the vast majority of the population, drank rum. Rum was the main drink in the taverns, but another type of liquor, called bumbo, also became prevelent among the pirates. This was a mix of rum, water, sugar, and nutmeg.[28]

However, after going through a Golden Age, piracy began to decline, under assualt from coordinated tactics by the French and British. Between 1716 and 1726, an estimated 400 to 600 British and American pirates went to the gallows. Captured pirates assending the noose were given one last chance to repent their life, and some experienced "gallow conversions." Before his execution in 1724, John Archer said that the "wickedness that has led me as much as any, to all the rest, has been my brutish drinking. by strong drink I been heated and hardened that are now more bitter then death upon me." John Browne, hanged at Newport in 1723, instructed "above all, do not let yourself be overcome with strong drink."[28]

However, most pirates went unchanged right up to the tightening of the noose. Historians believe the hand of the emerging Temperance movement was probably involved with these sudden, instantaneous conversions. Notably, the famous pirate William Kidd showed up at his execution badly drunk. And William Lewis, hanged in the Bahamas, who came dressed in red ribbon, heartily hollered for more drink.[28]

Literary assosiation[edit]

Perhaps the most famous literary assosiation of rum came from Robert Louis Stevenson's book Treasure Island. The novel would come to shape public impression of rum; no longer where they theiving scoundrals, but rather romantic one-legged men carrying parrots on their shoulders. In 1904, James Mattew Barrie created Peter Pan, basing Captain Hook on Stevenson's charecters. Among other things, Treasure Island shaped piracy's modern assosiation with rum (although the book wasn't the first to mention rum in lieu of piracy; Robinson Crusoe found "three large rumlets" of it in his fictitous island in 1719). The pirate Billy Bones displays an inherent fondness for the stuff, saying "I lived on rum. It's been meat and drink, and man and wife, to me." It's a predilection shared by the other pirates, including the unfortunate Captain Flint, who dies at the gallows in Savannah bellowing for rum, not unlike Captain Kidd.[29]

But the most defining appearence of rum in literature was a nonsensical rhyme first muttered by Billy Bones, but repeated again and again by the other pirates:

- Fifteen men on the dead man's chest

- Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

- Drink and the Devil have done for the rest

- Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

The poem is a dark and melencholy line, evidently composed by the author, although some have speculated that it was based on a traditional sea chanty, now lost. Ten years later, Young E. Allison stretched the lines out into a poem, which became the basis of a Broadway musical shortly therafter—forever anchoring rum's assosiation with pirates in the public imagination.[29]

[edit]

The association of rum with the Royal Navy began in 1655 when the British fleet captured the island of Jamaica. With the availability of domestically produced rum, the British changed the daily ration of liquor given to seamen in the Caribbean from French brandy to rum.[30] Rum was plentiful in the islands, had an almost indefinate life, actually improved over time, and was more potent then its lower-alclohol beer and wine kin, thus requiring less storage. Another push for the globalization of rum rations came from the sugar industry, which thought of the British navy as a lucrative market. In 1779, following a petition by the Society of West India Merchants, the British government officially ratified the distribution of rum, replacing brandy in the ship stores. This was the first, but not the last, time when the sugar and rum industries would link up to ensure one another's good fortune.[31]

"Some five hundred seamen have vanished from Jamacia since being in my command; which I believe to have all been seduced out and gone home with the homeward bound trade, through the temptations of high wages and 30 gallons of rum, and being generally conveyed drunk on board their ships from the punch houses were they are seduced."

— Admiral of the Navy Edward Vernon, in a letter to the British admirality.[31]

It is not hard to imagine why liquor was popular with sailors at the time. The average seaman was in his twenties, and generally came from a poor family, as the well-off tended not to risk the perils and dangers of life on the sea. The life of eighteenth-century mariners could be appalingly bleak; they were stuffed in bleak quarters with their comrades, with only enough room to string a hammock and a chest for storage. To them, rum offered a brief escape from life at sea. In addition, rum was safe and pallatable, wereas the food offered on board was neither.[31]

However, rum was seen as a great danger by officers in the navy. One important skill at the time was balancing morale and discipline, a balance made all the more difficult by the distribution of rum. it was hard enough to scramble quickly up a rigging during gusting winds or a galloping swell when stone sober, let alone drunk. In this way tipsy sailors were more likely to get injured. This was noticed by the admiral of the navy, Edward Vernon (after whom Lawrence Washington, George Washington's older brother, named Mount Vernon). Vernon regarded rum as a competitor for his men's affections, noting that its charms often made sailors to abandon their posts permanently. In addition, he disliked how sailors drunk their spirits by the dram, and often all at once.[31]

In an order issues at Port Royal in 1740, Vernon called for rum served to naval crews to be "mixed with the proportion of a quart of water for every half pint of rum," resulting in a concoction that was one part rum and four parts water. To ensure the impact of the spirit on his sailors would be reduced, he ordered the diluted rum to be distributed over two daily sessions instead of one, the first between ten and noon and the second between four and six. the order for diluted rum circulated throughout the fleet, and the new drink made its way out of the west India station. By 1756, the daily distribution of rum was codified in the Admirality's naval code.[31]

The mixture, which no longer possessed the "kick" of killd-devil, became known as grog. While it is widely believed that the term grog was coined at this time in honor of the grogram cloak Admiral Vernon wore in rough weather,[32] (or his derieved nickname"Old Grogram"[31]) the term has been demonstrated to predate his famous orders, with probable origins in the West Indies, perhaps of African etymology (see Grog).[33]

In a way, Vernon was ahead of his time. The same 1740 order that enacted the distribution of grog rather then "neat" rum also included a provision allowing sailors to exchange their salt and bread allotment for sugar and limes to make the [grog] more palatable to them." Although the order had more to do with the sailors' stomachs then with their health, this change would have a net positive effect on the Royal Navy. At the time, scurvy was a deadly disease that plauged sailors with bleeding gums, sore joints, slow healing, and loose teeth, yet for centuries it remained a medical mystery. Eum was issued as a premptive, but later experiments, starting around 1747, identified the source as a lack of absorbic acid, found prominently in—among others—citrus. two years later, the navy issued orders for a half-ounce of lime to be mixed with the sailor's daily rum or wine ration, something that Vernon had done years before, wether by luck or by instinct.[31]

Over time, the dispensing of grog became more fixed and cerimonial. Even diluted, the grog rations were equivelent to about five cocktails a day, agreeable by any standards—perhaps too agreeable. as the navy became more professional and the Temperance movement gained gained a foothold, rum rations fell further into disfavor. In 1823, the rum ration was cut in half, and then again in 1850—effectively culling the distribution of spirits by three-quarters in just under three decades. However, the navy did provide some compensative rewards, often an increase in tea, cocoa, and meat rations, as well as a token increase in pay. Additionally, as the amount of rum decreased, its quality increased. The navy's longtime blender and supplier, ED & F Man, decided to appeal to the more discreaning taste of officers, and soon developed a following among the upper ranks. The exact blend of the rum codified in 1810 by the Admirality was a heavily guarded secret.[31]

The tradition persisted well into the twentieth century, even as it began to fall out of favor with the navymen. By the 1950s, only about 30,000 opted for their daily rum ration. As technology advanced and navy operations advanced from hauling tar buckets, the value of distributing rum to on-duty saliors was questioned. The advent of the Breathalyzer didn't help, as after consuming his daily ration a sailor was legally drunk. By 1970, it ws hard to ignore the clamor regarding naval rum rations, and the House of Commons entered debate on the issue. The Secretary of Navy, seeing a looming defeat, lobbied for just compensation. In lieu of rum rations, a lump sum of 2.7 million pounds was donated to the Sailor's Fund, which paid for such things such as excrutions to foreign ports for mariners and better equipment at the navy base.[31]

July 31st, 1970 was known as Black Tot Day—the last day rum was officially rationed out to sailors. Around the world, British naval mariners wore black armbands and attended mock funerals. Among the most elaborate of these was on the HMS Fife, a guided missile destroyer based at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. the ship was the closest to the International Date Line, and thus the last one to dole out rum. the sailors tossed their rations, and the whole rum barrel, overboard. The historic moment was celebrated by a 21-gun salute, ending a 325 year-old tradition.[31]

Aftermath[edit]

Naval rum has a second, debased life that exists to this day. In 1980, the Admirality Board voted to give the rum's secret formula to the American entreprenuer Charles Tobias, who believed he would find a ready market among retired sailors and people intrested in its lore. In return, Tobias pledged monthly donations to the Sailor's Fund. The heavy, spiritfull rum was called "Pusser's," slang for purser (the ship's supply officer, formelly in charge of mixing the ship's rums), and is manufactured and sold throughout much of the world today. The exact composition of the blend is still a closely guarded secret; it is, broadly, a blend of heavy rums from Guyana and Trinidad leavened with three lighter rums.[31]

A story involving naval rum is that following his victory at the Battle of Trafalgar, Horatio Nelson's body was preserved in a cask of rum to allow transport back to England. Upon arrival, however, the cask was opened and found to be empty of rum. The pickled body was removed and, upon inspection, it was discovered that the sailors had drilled a hole in the bottom of the cask and drunk all the rum, in the process drinking Nelson's blood. Thus, this tale serves as a basis for the term Nelson's Blood being used to describe rum. It also serves as the basis for the term "Tapping the Admiral" being used to describe drinking the daily rum ration. The details of the story are disputed, as many historians claim the cask contained French Brandy whilst others claim instead the term originated from a toast to Admiral Nelson.[34] It should be noted that variations of the story, involving different notable corpses, have been in circulation for many years.[35]

Colonial Australia[edit]

- See Also: Rum Rebellion

Rum became an important trade good in the early period of the colony of New South Wales. The value of rum was based upon the lack of coinage among the population of the colony, and due to the drink's ability to allow its consumer to temporarily forget about the lack of creature comforts available in the new colony. The value of rum was such that convict settlers could be induced to work the lands owned by officers of the New South Wales Corps. Due to rum's popularity among the settlers, the colony gained a reputation for drunkenness even though their alcohol consumption was less than levels commonly consumed in England at the time.[36]

When William Bligh became governor of the colony in 1806, he attempted to remedy the perceived problem with drunkenness by outlawing the use of rum as a medium of exchange. In response to this action, and several others, the New South Wales Corps marched, with fixed bayonets, to Government House and placed Bligh under arrest. The mutineers continued to control the colony until the arrival of Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1810.[37]

Decline[edit]

Following its heyday in the eighteenth century, rum went into a heavy decline. The chief problems was with molasses, or the lack of it; after about the time of the Revolutionary War, molasses greatly increased in both rarity and expense. The British West Indian planters, still under the gaze of the crown, were bound by the Navigation Acts, which prohibited any trade by British colonies with foreign entities other then Britian—which now included the freshly minted United States, the chief producer of rum at the time. Wheras the distillers could at first obtain resources from French and Spanish islands, these doors began to close as well. In 1783, Spain abruptly shut Cuban ports to America, and captured two US ships over a spat about American settlers in Spanish-held Florida. French ports, the chief suppliers, followed soon therafter due to political intrigue; In any event, the French had by then begun to invest in their own rum industry, and molasses was no longer being seen as something to be traded away cheaply for a few sticks of lumber.[38]

Trade opened up between the West Indies and America following the War of 1812, but by then the sugar plantations themselves were in steep decline. Depleted by over two centuries worth of sugar production, a great amount of manure (a fertilizer) was needed to maintain the islands. In addition, by then Britian had begun to emancipate slaves, and without a steady supply of labor, the plantations began to shut down. The small islands that at one point had been considered more valuable then all of Canada were pushed into the margin, and hardly made a reliable supply line anymore.[38]

Hear the happy voices ringing

As "King Rum" is downward hurled,

Souting vict'ry and hosanna

In their march to save the world.

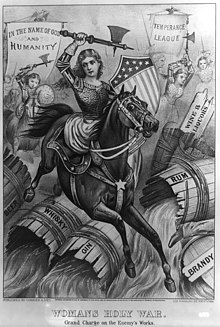

— Women's Christian Temperance Movement Union song, late 19th century.[39]

Supply was only half of the problem; demand for rum greatly declined during the course of the ninteenth century. Following the development of American nationalism, rum was seen as a relic of the past, a product associated with Britisn rule. Wheras drinking rum had at once been a source of personal afflunece and independance for the colonists, now it was seen with no little distaste. throughout the colonies, drinkers made the switch to other drinks. the distilling buisness did likewise; they retooled, and reemerged making such popular drinks such as gin and whiskey—the latter of the which was almost unheard off in early American taverns. The effect spread to Europe, which had always had different tastes, hence the small market for rum there, and Africa, where for a time it had been a valuable trading commodity in the slave market. By 1888, the huge number of Boston distilleries had shrunk down to three.[40]

Prohabition years[edit]

The emerging temperance movement finally fully mantifisted itself in full during the late 19th and early 20th century, circumstating in the Prohibition Act in 1920, which made the sale of all alcloholic beverages illegal. In one of the greatest failures in American history, instead of banning liquor, the law actually amplified its mistique.[41]

When the ban on liquor went into effect in January 1920, hundreds of American distilleries shut down. This in turn triggered the greatest coast-to-coast science project in American history, as, curious Americans suddenly found fasination in the mysterious properties of yeast. Vendors soon sold apparatuses for creating homemade liquor, including barrels for aging spirits and and simple stills that could prossess one to five-gallon batches. More ambitious moonshiners fired up backcountry stills to meet demand; white lightning and "corn-licker" moved through homes and speakesies like wildfire.[41]

In addition Prohabition sparked a massive rise in tourism, to wherever there was drink—practically everywhere but Finland, which had established its own Prohibition in 1919. among the most famous destinations was Cuba. Just a short hop from Florida, the island was redolent of adventure, romance, and liquor. "Havana," Fortune magazine noted, "became the unofficial United States saloon." It was here that rum would rise again. The New England visitors noticed something fascinating that pleased them greatly; a light, crisp Jamacian-style rum that was the ode of the heavy, dark New England rums of the past.[41]

Origins of the new rum[edit]

The new style of rum can trace its history back to 1836, the year that a fifteen year-old Catalonian immigrant named Facundo Bacardi arrived with his family at the elegant Cuban settlement of Santiago. Facundo set himself up as an importer and seller of wine and other spirits, and in 1862 purchased, with his brother, a modest Santiago distillery owned by an Englishman named John Nunes. He soon started to produce rum, and his highly successful drink was named the "bat drink," after the bats that lived either in the rafters of the distillary or as a colony in the trees in the yard outside it.[42]

Barcadi set out make the harsh, often disagreeable rums into a smother, crisper form that could be liked by a wider audience. His breakthrough was a filthering system that removed the heavy oil impurites that made it so harsh (the filther remains a family secret, but is thought to be a mixture of charcol and sand). Barcadi also toyed with different woods for his casks and in bleeding the product with other materials, until he arrived at his ideal product. The new version of rum went on to become a breakthrough; travellers discovered that it mixed well with anything, be it limes, eggs, grape, or even seltzer, from which mismo originated.[42] Rum had suddenly transformed into was film-maker Basil Woon called "a gentlemen's drink," "by the grace of a family named Barcardi and of American prohibition."[41]

Repeal and regrowth[edit]

"While a great deal of inferior 'fire water' rum is likely to be sold in the United States for several years, the better quality rum made from genuine sugar can be obtained in increasing measure...and the industry is confindent for restoring the taste of a liqour that was once inextricably woven with the romantic history of Early America."

— Literary Digest magazine, 1934[43]

"Perhaps the fanatical dry will object to the latest discovery the drinking public of America is making—the discovery of rum. The American public has been a little delayed in discovering this beverage, but according to reports from the West Indies and other Carribean isles, a rum boom is under way, after many years of sad decline...Perhaps because it was impossible to imitate, the years of Prohabition have made us forget just how efficent and tasty a beverage it is. But now the public taste is turning back to the memory of its ancestors, and rum is arriving, or about to arrive, on our shores in staggering quantities."

— New Outlook magazine, 1934[43]

In 1933, the 18th amendment was repealed, and the lawfulness of drinking restored. No spirit benefited from the repeal as much as rum did. With ample supplies and a developing taste for the drink in America, rum again came back onto the scene.[43]

The rum that came to America was very different from the one that had left it centuries earlier. Advances in chemistry, distillation, sanitation, engineering, and fermentation meant that the buisness was no longer affable to a large group of small-time producers, as it had been in the past. Larger, well funded companies like the US's National Distillers, Cuba's Bacardi, Jamacia's Wray & Nephew, and Barbados's Mount Gay came to dominate the industry.[43]

There was also a massive change with the development of branding. In the past, distillers had shipped rum in plain barrels to an undemanding public indifferent to what brand or what company made their rum. With the rising demand came branding, competition for the crowded store shelves, and the need to anticipate what to consumer base wanted. The last was easy enough; distillers quickly realized that the public wanted a clean, crisp, light "Cuban rum," one that mixed well with anything. Cuba's rum, and specifically Barcadi, remained the rum to beat. Other locations worked to improve their industries, most decisively Puerto Rico, which banned innate mixing with nuetral substances and decreed that all Puerto Rican rum must be aged at least one year. They were largly successful, and further aided by their status as an American territory, which allowed them to ship their rum without taxation.[43]

Barcadi rum remained the rum to beat. It was so dominent that drinkers in the United States used "Barcadi" and "rum" interchangably. Although this was good for a company dependant on branding, it also meant that suitors could slip in non-Barcadi rum into a drink, something that greatly agitated the Barcadi family. In 1936, the company took the unusual step of suing two bars—the barbizon Plaza Hotel and Wivel's Restaurant, both in New York City—in an effort to get them to stop selling another company's products under the Barcadi name. The New York State Supreme Court agreed; they decreed that all Barcadi cocktails must contain Barcadi rum.[43]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Pacult, F. Paul (July 2002). "Mapping Rum By Region". Wine Enthusiast Magazine.

- ^ Blue p. 72

- ^ a b c d e f Wayne (2006). p.14-15

- ^ a b Blue p. 70

- ^ a b Wayne (2006). p.26

- ^ Wayne (2006). p.18-20

- ^ a b c Wayne (2006). p.24-27

- ^ a b c d e f Wayne (2006). p.27-29

- ^ a b c Wayne (2006). p.29-31

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Wayne (2006). p.42-47

- ^ Blue p. 74

- ^ Roueché, Berton. Alcohol in Human Culture. in: Lucia, Salvatore P. (Ed.) Alcohol and Civilization New York: McGraw-Hill, 1963 p. 178

- ^ a b c d e Wayne (2006). p.70-73

- ^ a b Wayne (2006). p.68-70

- ^ Blue p. 76

- ^ a b Tannahill p. 295

- ^ Wayne (2006). p.96-99

- ^ Tannahill p. 296

- ^ Frost, Doug (January 6, 2005). "Rum makers distill unsavory history into fresh products". San Francisco Chronicle.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Rorabaugh p. 152-154

- ^ a b c d e f g Wayne (2006). p.73-79

- ^ Wayne (2006). p.92

- ^ a b c d e Wayne (2006). p.102-105

- ^ a b c Wayne (2006). p.105-109

- ^ a b Wayne (2006). pg.109-110

- ^ Wayne (2006). pg.111-112

- ^ Pack p. 15

- ^ a b c d e f Wayne (2006). p.47-50

- ^ a b Wayne (2006). p.61-63

- ^ Blue p. 77

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Wayne (2006). p.54-61

- ^ Tannahill p. 273

- ^ Pack p. 123

- ^ Blue p. 78

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara (2006-05-09). "Body found in barrel". Urban Legends Reference Pages. Snopes.com. Archived from the original on 2009-01-15. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ^ Clarke p. 26

- ^ Clarke p. 29

- ^ a b Wayne (2006). p.136-137

- ^ Wayne (2006). p.134

- ^ Wayne (2006). p.137-139

- ^ a b c d Wayne (2006). p.162-166

- ^ a b Wayne (2006). p.166-170

- ^ a b c d e f Wayne (2006). p.178-181

References[edit]

- Curtis, Wayne (2006). And a bottle of rum - a history of the New World in ten cocktails. Crown Publishers. p. 285. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/1-400-5167-3|[[Special:BookSources/1-4000-5167-3|1-400-5167-3]]]].

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) (author inteview) - Clarke, Frank G. (2002). The History of Australia. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31498-5.

- Cooper, Rosalind (1982). Spirits & Liqueurs. HPBooks. ISBN 0-89586-194-1.

- Foley, Ray (2006). Bartending for Dummies: A reference for the Rest of Us. Wiley Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-470-05056-X.

- Pack, James (1982). Nelson's Blood: The Story of Naval Rum. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-944-8.

- Tannahill, Reay (1973). Food in History. Stein and Day. ISBN 0-8128-1437-1.

Further reading[edit]

- Arkell, Julie (1999). Classic Rum. Prion Books.

- Coulombe, Charles A (2004). Rum: The Epic Story of the Drink that Changed Conquered the World. Citadel Press.

- Smith, Frederick (2005). Caribbean Rum: A Social and Economic History. University Press of Florida. (Introduction)