User:Punetor i Rregullt5/sandbox/Comparison of cheetahs, jaguars and leopards

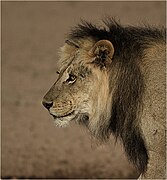

| Southern lion | |

|---|---|

| |

| A male at Etosha National Park, Namibia | |

| |

| A lioness at Samburu National Reserve, Kenya | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | P. l. melanochaita

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera leo melanochaita (Ch. H. Smith, 1842)

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

formerly:

| |

The Southern lion (Panthera leo melanochaita),[2][3] also referred to as the East-Southern African lion,[4] is a subspecies of the lion in Southern and East Africa.[5][6] In this part of Africa, lion populations are regionally extinct in Lesotho, Djibouti and Eritrea.[7] Since the turn of the 21st century, lion populations in intensively managed protected areas in Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe have increased, but declined in East African range countries.[8] They are threatened by loss of habitat and prey base, killing by local people in retaliation for loss of livestock, and in several countries also by trophy hunting.[7] The type specimen for P. l. melanochaita was a black-maned lion from the Cape of Good Hope, known as the Cape lion, and consequently, the scientific name was initially meant for it. The lion population in this part of South Africa is extinct.[9]

Taxonomic history[edit]

Charles Hamilton Smith described the type specimen for Panthera leo melanochaita in 1842 using the scientific name Felis (Leo) melanochaitus.[10] It was referred to as the "Southern relative" of the North African lion.[2][3] In the 19th and 20th centuries, several naturalists described specimens from Southern and East Africa and proposed subspecies, including:

- Felis leo somaliensis (Noack 1891), based on two lion specimens from Somalia[11]

- Felis leo massaicus (Neumann 1900), based on two lions killed near Kibaya and the Gurui River in Kenya[12]

- Felis leo sabakiensis (Lönnberg 1910), based on two lions from the environs of Mount Kilimanjaro[13]

- Felis leo bleyenberghi (Lönnberg 1914), a male lion from the Katanga Province of Belgian Congo[14]

- Felis leo roosevelti (Heller 1914), a lion from the Ethiopian Highlands presented to Theodore Roosevelt[15]

- Felis leo nyanzae (Heller 1914), a lion skin from Kampala, Uganda[15]

- Leo leo hollisteri (Joel Asaph Allen 1924), a male lion from the area of Lime Springs, Sotik on the eastern shore of Lake Victoria[16]

- Leo leo krugeri (Austin Roberts 1929), an adult male lion from the Sabi Sand Game Reserve named in honour of Paul Kruger[17]

- Leo leo vernayi (Roberts 1948), a male lion from the Kalahari collected by the Vernay-Lang Kalahari Expedition[18]

- Panthera leo webbensies Ludwig Zukowsky 1964, two lions from Somalia, one in the Natural History Museum, Vienna that originated in Webi Shabeelle, the other kept in a German zoo that had been imported from the hinterland of Mogadishu.[19]

Dispute over the validity of these purported subspecies continued among naturalists and curators of natural history museums until the early 21st century.[9][20][21][22][1] In the 20th century, some authors supported the view of the Cape lion being a distinct subspecies.[17][20][21][23] In 1939, the American zoologist Allen also recognized F. l. bleyenberghi, F. l. krugeri and F. l. vernayi as valid subspecies in Southern Africa, and F. l. hollisteri, F. l. nyanzae and F. l. massaica as valid subspecies in East Africa.[20] Pocock subordinated lions to the genus Panthera in 1930, when he wrote about Asiatic lions.[24] Ellerman and Morrison-Scott recognized only two lion subspecies in the Palearctic realm, namely the African P. l. leo and the Asiatic P. l. persica.[25] Various authors recognized between seven and 10 African lion subspecies.[22] Others followed the classification proposed by Ellerman and Morrison-Scott, recognizing two subspecies including one in Africa.[26] In the 1970s, the scientific name P. l. vernayi was considered synonymous with P. l. krugeri.[22] In 1975, Vratislav Mazák hypothesized that the Cape lion evolved geographically isolated from other populations by the Great Escarpment.[9] In the early 21st century, Mazák's hypothesis about a geographically isolated evolution of the Cape lion was challenged. Genetic exchanges between populations in the Cape, Kalahari and Transvaal Province regions and farther east are considered having been possible through a corridor between the Great Escarpment and the Indian ocean.[27][6] In 2005, the authors of Mammal Species of the World recognized P. l. bleyenberghi and P. l. krugeri, P. l. vernayi P. l. massaica, P. l. hollisteri and P. l. nyanzae as valid taxa.[1] In 2016, IUCN Red List assessors subsumed all African lion populations to P. l. leo.[7] In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the Cat Specialist Group reduced the number of valid lion subspecies in Southern and Southeast Africa to one, namely P. l. melanochaita.[5]

Genetic research[edit]

Since the beginning of the 21st century, several phylogenetic studies were conducted to aid clarifying the taxonomic status of lion samples kept in museums and collected in the wild. Scientists analysed between 32 and 197 lion samples from up to 22 countries. Based on the results of a genetic analyses, it appears that the species comprises two main evolutionary groups, one in Southern and East Africa, and the other in the northern and eastern parts of its historical range; these groups diverged about 50,000 years ago.[28] It was assumed that tropical rainforest and the East African Rift constituted major barriers between the two groups.[6][29][30][31][32] Based on this assessment, the species comprises two recognised subspecies:[5]

- P. l. leo in the northern and eastern regions of the species' historical and contemporary distribution

- P. l. melanochaita in Southern and East African range countries.

The two groups were in contact in Ethiopia or northern parts of East Africa.[32] A phylogeographic analysis of 194 lion sequences from 22 countries indicated that East African and Southern African lions form a clade that diverged about 186,000–128,000 years ago from the clade formed by North, West and certain Central African lions. In 9 of 19 lion samples from Ethiopia, haplotypes of the Central African lion group were found, indicating that the Great Rift Valley was not a complete barrier to gene flow; southeastern Ethiopia is considered a genetic admixture zone between Central and East African lions.[33] Since 2005, several phylogeographic studies were conducted to aid clarifying the taxonomic status of lion samples kept in museums and collected in the wild. Results of a DNA analysis using 26 lion samples from Southern and East Africa indicate that genetic variation between them is low and that two major clades exist: one in southwestern Africa and one in the region from Uganda and Kenya to KwaZulu-Natal. Five lion samples from Kenya's Tsavo East National Park showed identical haplotypes as three lion samples from the Transvaal region in South Africa.[34] Results of phylogeographic studies support the notion of lions in Southern Africa being genetically close, but distinct from populations in West and North Africa and Asia.[29][35] Based on the analysis of samples from 357 lions from 10 countries, it is thought that lions migrated from Southern Africa to East Africa during the Pleistocene and Holocene eras.[29] A phenotypic and DNA analysis was conducted using samples from 15 captive lions in the Addis Ababa Zoo and from six wild lion populations. Results showed that the captive lions were genetically similar to wild lions from Cameroon and Chad, but with little signs of inbreeding.[36] Lions samples from Gabon's Batéké Plateau National Park and Odzala-Kokoua National Park in Republic of the Congo were found to be related to the Southern lion clade.[37]

Characteristics[edit]

The lion's fur varies in colour from light buff to dark brown. It has rounded ears and a black tail tuft. Average head-to-body length of male lions is 2.47–2.84 m (97–112 in) with a weight of 148.2–190.9 kg (327–421 lb). The largest East African lion measured 3.33 m (10.9 ft). Females are smaller and less heavy.[38] The Cape lion had a black mane extending beyond the shoulders and under the belly.[10] Yet, black-maned lions also occur in the Kalahari and eastern Okavango Delta alongside those with a normal tawny colour.[39] Until the late 20th century, mane colour and size was thought to be a distinct subspecific characteristic.[22][9] In 2002, research in Serengeti National Park revealed that mane darkens with age; its colour and size are influenced by environmental factors like temperature and climate, but also by individual testosterone production, sexual maturity and genetic precondition. Mane length apparently signals fighting success in male–male relationships.[40] An exceptionally heavy male near Mount Kenya weighed 272 kg (600 lb).[41] Male lions killed in East Africa were less heavy than lions killed by hunters in Southern Africa.[42] The captive male lions at Addis Ababa Zoo have darker manes and smaller bodies than those of wild populations.[36] White lions have occasionally been encountered in and around Kruger National Park and the adjacent Timbavati Private Game Reserve in South Africa. Their whitish fur is a rare morph caused by a double recessive allele.[43]

Manes[edit]

In the 19th and 20th centuries, lion type specimen were described on the basis of mane size and colour.[44] Male East African lions are known for a great range of mane types. Mane development is related to age: older males have more extensive manes than younger ones; manes continue to grow up to the age of four to five years, long after lions have become sexually mature. Males living in the highlands above 800 m (2,600 ft) elevation develop heavier manes than lions in the more humid and warmer lowlands of eastern and northern Kenya. The latter have thinner manes, or are even completely maneless.[45] Hence, lion manes reflect ambient temperature. The mane colour is also influenced by nutrition and testosterone. Its length is an indicator for age and fighting ability of the lion.[40] A male lion specimen from Somalia had a short mane.[22] Male lions from the Ethiopian highlands had dark and heavy manes with black tips that extended over the whole throat and chest to the forelegs and behind the shoulders.[15] A few lions observed in the environs of Mount Kilimanjaro had tawny to sandy coloured manes as well.[14] Two male lions observed in the border region between Kenya and Tanzania had moderate tufts of hair on the knee joint, and their manes appeared brushed backwards. They were less cobby with longer legs and less curved backs than lions from other African range countries.[12] Mane colour of males in Kenya vary between tawny, isabelline and light reddish yellow.[44] Tsavo male lions generally do not have a mane, though colouration and thickness vary. There are several hypotheses as to the reasons. One is that mane development is closely tied to climate because its presence significantly reduces heat loss.[46] An alternative explanation is that manelessness is an adaptation to the thorny vegetation of the Tsavo area in which a mane might hinder hunting. Tsavo males may have heightened levels of testosterone, which could also explain their reputation for aggression.[47] The weak or absent mane of Tsavo lions is a feature, which was characteristic also for the extinct lions of ancient Egypt and Nubia. Adult lion males in Egyptian art are usually depicted without a mane, but with a ruff around the neck.[48]

White lion[edit]

The white lion is a rare morph with a genetic condition called leucism, which is caused by a double recessive allele. It has normal pigmentation in eyes and skin. White individuals have been occasionally encountered only in and around Kruger National Park and the adjacent Timbavati Private Game Reserve in eastern South Africa. They were removed from the wild in the 1970s, thus decreasing the white lion gene pool. Nevertheless, 17 births have been recorded in five different prides between 2007 and 2015.[43] White lions are selected for breeding in captivity.[49] Reportedly, they have been bred in camps in South Africa for use as trophies to be killed during canned hunts.[50]

Records[edit]

In 1936, a man-eating lion shot by Lennox Anderson, outside Hectorspruit in Eastern Transvaal weighed about 313 kg (690 lb) and was considered to be the heaviest wild lion. The longest wild lion reportedly was a male shot near Mucusso in southern Angola in 1973.[51][52]

Distribution and habitat[edit]

The southern lion was originally found from Ethiopia and Uganda in the north to the Cape of Good Hope in the south. Supported by genetic research, the border between the Southern and Northern subspecies runs through Ethiopia. Southeastern Ethiopia is considered a genetic admixture zone between the two groups. Within the Southern lion, genetic research identified three clades. These are the Northeastern, East-Southern and Southwestern subclade.[33] In East and Southern Africa, the population of lions declined in:

- Somalia since the early 20th century.[54] Intensive poaching since the 1980s and civil unrest posed a threat to lion persistence.[55][56]

- Uganda to near extinction in the 20th century.[57]

- Kenya in the 1990s due to poisoning of lions and poaching of lion prey species.[55]

- Rwanda and Tanzania due to killing of lions during the Rwandan Civil War and ensuing refugee crisis in the 1990s.[55]

- Malawi and Zambia due to illegal hunting of prey species in protected areas.[55]

- Botswana due to intensive hunting and conversion of natural habitats for settlements since the early 19th century.[58]

- Namibia due to massive killing of lions by farmers since at least the 1970s.[59]

- South Africa since the early 19th century in the Natal and Cape Provinces south of the Orange River, where the Cape lion population was eradicated by 1860.[9] A few decades later, lions in the Highveld north of the Orange River were also eradicated.[38] In the Transvaal, lions occurred historically in the Highveld as well, but were restricted to eastern Transvaal's Bushveld by the 1970s.[60]

Contemporary lion distribution and habitat quality in East and Southern Africa was assessed in 2005, and Lion Conservation Units (LCU) mapped.[4] Between 2002 and 2012, educated guesses for size of populations in these LCUs ranged from 33,967 to 32,000 individuals.[55][61]

| Range countries | Lion Conservation Units | Area in km2 |

|---|---|---|

| Democratic Republic of Congo | Massif D'itombwe, Luama | 8,441[4] |

| Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda | Queen Elizabeth-Virunga | 5,583[62] |

| Uganda | Toro-Semulik, Lake Mburo, Murchison Falls | 4,800[63] |

| Somalia | Arboweerow-Alafuuto | 24,527[4] |

| Somalia, Kenya | Bushbush-Arawale | 22,540[4] |

| Kenya | Laikipia-Samburu, Meru and Nairobi National Parks | 43,706[61] |

| Kenya, Tanzania | Serengeti-Mara and Tsavo-Mkomazi | 75,068[53] |

| Tanzania | Dar-Biharamulo, Ruaha-Rungwa, Mpanga-Kipengere, Tarangire, Wami Mbiki-Saadani, Selous | 384,489[53] |

| Tanzania, Mozambique | Niassa | 177,559[64] |

| Mozambique | Cahora Bassa, Gilé, Gorongosa-Marromeu | 82,715[64] |

| Mozambique, Zambia | Middle Zambezi | 64,672[64] |

| Mozambique, South Africa | Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park | 150,347[64] |

| Zambia | Liuwa Plains, Sioma Ngwezi, Kafue Sumbu Complex | 72,569[61] |

| Zambia, Malawi | North-South Luangwa | 72,992[61] |

| Malawi | Kasungu, Nkhotakota | 4,187[61] |

| Zimbabwe | Mapungubwe, Bubye | 10,033[61] |

| Botswana, Zimbabwe | Okavango-Hwange | 99,552[61] |

| Botswana | Xaixai | 12,484[4] |

| Botswana, South Africa | Kgalagadi | 163,329[61] |

| Angola | Kissama-Mumbondo, Bocoio-Camacuio, Alto Zambeze | 393,760[4] |

| Angola, Namibia | Etosha-Kunene | 123,800[4] |

| Namibia | Khaudum-Caprivi | 92,372[4] |

The LCUs Ruaha-Rungwa, Serengeti-Mara, Tsavo-Mkomazi and Selous in East Africa, as well as Luangwa, Kgalagadi, Okavango-Hwange, Mid-Zambezi, Niassa and Greater Limpopo in Southern Africa are currently considered as lion strongholds. These LCUs host more than 500 individuals each, and the population trend is stable there.[61]

Admixture zone to the Northern subspecies[edit]

One of the largest lion populations in Ethiopia is found in Gambella. According to genetic research, this population, which is contigous with populations in Sudan, does not belong to the Southern subspecies but to the Northern lion. The same is probably true for the populations in northern Ethiopia,[33] where, a group of lions was recorded in 2016 in Alatash National Park close to the international border with Sudan.[65][66][67] Other parts of Ethiopia, which still have lions fall into the admixture zone. These are Omo and Bale Mountains National Parks, the ara around the Chew Bahir and Turkana lakes, and the Webi Shabeelle area.[68] In 2009, a small group of less than 23 lions were estimated in Nechisar National Park located in the Great Rift Valley. This small protected area in the Ethiopian Highlands is encroached by local people and their livestock.[69] Lions of northern Uganda have not been analysed genetically[33] and might belong to the Northern subspecies. In northern Uganda, lions are present in Kidepo Valley and Murchison Falls National Parks.[68][61]

Northeastern clade[edit]

The range of the Northeastern clade outside the admixture zone is confined to Somalia and northern and central Kenya.[33] Already in the 1980s, the lion population in Somalia had greatly declined due to poaching and was restricted to woodlands in the southern part of the country.[56] In northern Kenya, lions had been observed near Kavirondo, near Lake Manyara and in the Tanga Region in the late 19th century.[12] By the 21st century, lion populations in northern Kenya have been fragmented.[70]

| Range countries | Area used in km2 | Estimated no. of individuals |

|---|---|---|

| Laikipia-Samburu complex in Kenya | 35,511 | 271[61] |

| Meru in Kenya | 7,365 | 40[61] |

| Arawale complex in Kenya and Somalia | 22,540 | 750[61] |

| Arboweerow-Alafuuto in Somalia | 24,527 | 175[61] |

| Total | XXX | XXX |

Southern / Eastern clade[edit]

This is the clade with the largest remaining populations. The range of this clade extends from southern Kenya, southern Uganda and the Virunga area in the Democratic Republic of the Congo southward to the Cape of Good Hope, excluding only the western parts of Southern Africa.[33] The following complexes are considered lion strongholds of the Southern/Eastern clade:[61]

- Ruaha National Park cum Rungwa Game Reserve

- Serengeti National Park cum Maasai Mara

- Tsavo East National Park, Tsavo West National Park with Mkomazi National Park

- Selous Game Reserve

- North Luangwa National Park and South Luangwa National Park

- Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park

- Niassa Reserve

- Zambezi National Park with adjacent protected areas along Zambezi River in Zambia and Mozambique

Lions in Queen Elizabeth National Park, which form a contiguous population with lions in Virunga National Park in the northeastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo,[61][62][68] do belong to the Southern Eastern clade.[33] In 2010, the lion population in Uganda was estimated at 408 ± 46 individuals in three protected areas including Queen Elizabeth, Murchison Falls and Kidepo Valley National Parks. Other protected areas in the country probably host less than 10 lions.[71] As of 2006, there were an estimated 675 lions in the Tsavo area, out of the 2,000 total in Kenya.[72] Between 2004 and 2013, lion guardians around Amboseli National Park identified 65 lions in an area of 3,684 km2 (1,422 sq mi).[70] A small population is present in Rwanda's Akagera National Park, estimated at 35 individuals at most in 2004.[68] The lion population in South Africa's former Natal and Cape Provinces is locally extinct since the mid 19th century.[73] The last lions south of the Orange River were sighted between 1850 and 1858.[9] Between 2000 and 2004, 34 lions were reintroduced to eight protected areas in the Eastern Cape Province, including Addo Elephant National Park.

| Range countries | Area used in km2 | Estimated no. of individuals |

|---|---|---|

| Virunga and Queen Elizabeth National Park in CAR and Uganda | 5,583 | 210[61] |

| Lake Mburo in Uganda | 373 | 3[61] |

| Luama Hunting Reserve in DRC | 5,197 | <50[61] |

| Itombwe Massif in DRC | 3,244 | <50[61] |

| North West Tansania | 4,703 | 105[61] |

| Ruaha-Rungwa in Tanzania | 195,993 | 3,779[61] |

| Mpanga Kipengere in Tanzania | 958 | 14[61] |

| Swaga Swaga in Tanzania | 7,242 | 102[61] |

| Serengeti-Mara in Tanzania and Kenya | 35,852 | 3,673[61] |

| Nairobi in Kenya | 830 | <30[61] |

| Tsavo-Mkomazi in Kenya and Tanzania | 39,216 | 880[61] |

| Tarangire In Tanzania | 28,771 | 731[61] |

| Wami Mbiki-Saadani in Tanzania | 8,787 | 136[61] |

| Selous in Tanzania | 138,035 | 7,644[61] |

| Niassa in Mozambique, Tanzania | 177,559 | 1,573[61] |

| Liuwa Plains in Zambia | 3,866 | 4[61] |

| Kafue in Zambia | 58,898 | 386[61] |

| Nsumbu in Zambia | 5,650 | <50[61] |

| Luangwa in Zambia | 72,992 | 574[61] |

| Kasungu in Malawi | 2,341 | 4[61] |

| Nkhotakota in Malawi | 1,846 | 18[61] |

| Kgalagadi in South Africa and Botswana | 163,329 | 800[61] |

| Mid-Zambezi in Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Mozambique | 64,672 | 755[61] |

| Tete South of Cahora Bassa, Gile and Gorongosa-Marromeu in Mozambique | 13,612, 22,322, 46,781 | 59, 45, 229[61] |

Limpopo admixture zone[edit]

The area of the Kruger National Park, which is part of the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park, is an admixture zone between the Southern-Eastern and the Southwestern clade. This area is a lion stronghold with about 2,300 lions.[61]

Southwestern clade[edit]

The only stronghold of the Southwestern clade is in the western parts of the Kavango–Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area, including Okavango Delta and Hwange National Park[74][61] Another important reserve for this clade is the Etosha National Park.[61] Lions are considered regionally extinct in the southwestern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[7][41] In Gabon, the presence of lions in Batéké Plateau National Park was doubtful in 2010.[75] In 2015, a camera trap recorded a single male lion in this national park.[76] Continued camera trapping in the area for more than one year recorded the same lion repeatedly. Its hair samples were collected for phylogenetic analysis and compared with tissue samples of lions from Gabon and Republic of the Congo that were killed in the 20th century. Results indicate that this individual is closely related to the ancestral lion population of the area, and that its DNA shows a typical Southern lion haplotype. It is considered possible that this lion dispersed to the area from Namibia or Botswana.[37] In the Republic of the Congo, the Odzala-Kokoua National Park was considered a lion stronghold in the 1990s. By 2014, no lions were recorded in the protected area, so that now, the species is considered locally extinct in the country.[77]

| Range countries | Area used in km2 | Estimated no. of individuals |

|---|---|---|

| Southwestern clade | ||

| Kissama-Mumbondo in Angola | 4,593 | <10[61] |

| Bocoio-Camucuio in Angola | 22,005 | 55[61] |

| SE Angola | 386,962 | 1,905[61] |

| Sioma Ngwezi in Zambia | 4,155 | <50[61] |

| Etosha-Kunene in Namibia | 123,800 | 455[61] |

| Khaudum-Caprivi in Namibia | 92,372 | 150[61] |

| Xaixai in Botswana | 12,484 | 75[61] |

| Okavango-Hwange | 99,552 | 2,300[61] |

| Greater Mapungubwe in Botswana, South Africa and Zimbabwe | 5,158 | 25[61] |

| Bubye in Zimbabwe | 4,875 | 200[61] |

| Total | XXX | XXX |

Behaviour and ecology[edit]

The lion is a social cat, living in groups of related individuals with their offspring. Such a family group is called a 'pride'. The average pride consists of around 15 lions, including several adult females and up to four males and their cubs of both sexes. Large prides, consisting of up to 30 individuals, have also been observed. Male lion groups are called a 'coalition'. Membership only changes with the births and deaths of female lions. Male cubs are excluded from their maternal pride when they reach maturity at around 2–3 years of age.[78] The sole known exception of this pattern is the Tsavo lion pride, which always has just one adult male.[79] Male lions spend years in a nomadic phase before gaining residence in a pride.[80] In 1966, a program was started to monitor lions in Serengeti National Park.[78] Between 1966 and 1972, two observed prides had between seven and ten females each. On average, females had litters once in 23 months.[81] Two or three cubs comprised the litters, and only twelve managed to grow to the age of two, out of 87 cubs born until 1970. Cubs died due to starvation in months Factors that contributed to the deaths of cubs were starvation, when large prey was not available, or when new males took over the prides. Between 1974 and 2015, prides were monitored again, and until 2012, 471 coalitions comprising 796 male lions entered a study area of 2,000 km2 (770 sq mi). Of these, 35 coalitions included male lions that were born in this place but had left and returned after being absent for about two years. Nomadic coalitions gain residency at between 3.5 and 7.3 years of age.[82] Results of a 10-year long survey on 50 radio-collared lions in the Kavango–Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area show that adult lions preferred grassland and shrubland habitat, but avoided woodlands and areas with high human density; by contrast, subadult dispersing male lions avoided grasslands and shrublands, but moved in human-dominated areas to a larger extent. Hence, dispersing lions are more vulnerable to coming into conflict with humans than adult lions.[83] In the Serengeti National Park, lions were observed to also scavenge on carrion when the opportunity arises. They scavenged animals that were killed by other predators, or died from natural causes. They kept a constant lookout for circling vultures, apparently being aware that vultures indicate a dead animal. Sympatric predators include the leopard, cheetah, hyena and African wild dog.[78][80]

Hunting and diet[edit]

Lions usually hunt in groups and prey foremost on ungulates such as gemsbok (Oryx gazella), Cape buffalo (Syncerus caffer), blue wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus), giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis), common eland (Tragelaphus oryx), greater kudu (T. strepsiceros), nyala (T. angasii), roan antelope (Hippotragus equinus), sable antelope (H. niger), plains zebra (Equus quagga), bushpig (Potamochoerus larvatus), common warthog (Phacochoerus africanus), hartebeest (Alcephalus buselaphus), common tsessebe (Damaliscus lunatus), waterbuck (Kobus ellipsiprymnus), kob (K. kob) and Thomson's gazelle (Eudorcas thomsonii). Their prey is usually in the range of 190–550 kg (420–1,210 pounds).[84] In the Serengeti National Park, lions were observed to also scavenge on carrion of animals that were killed by other predators, or died from natural causes. They kept a constant lookout for circling vultures, apparently being aware that vultures indicate a dead animal.[85] Faeces of lions collected near waterholes in Hwange National Park also contained remains of climbing mice (Dendromus) and common mice (Mus).[86]

In Botswana's Chobe National Park, lions also prey on African bush elephants (Loxodonta africana). They successfully attacked 74 elephants between 1993 and 1996, of which 26 were older than nine years, and one bull over 15 years old.[87] In October 2005, lions killed eight elephants aged between one and 11 years, and two of them older than eight years.[88]

Attacks on humans[edit]

- In the 19th century, north of Bechuanaland, a lion non-fatally attacked David Livingstone, who was defending a sheep in a village.[89]

- Two Tsavo males have been known as man-eaters, after an incident during the building of the Uganda Railway in the 1890s. Their skulls and skins are part of the zoological collection of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, the United States of America.[90][91] The total number of people killed is unclear, but allegedly 135 people fell victim to these lions in less than a year before Colonel John Patterson killed them.[92]

- The "Njombe lions" were a pride of lions in Njombe, in what was then Tanganyika, which for over three generations are thought to have preyed on 1,500 to 2,000 people. They were eventually dispatched by George Rushby.[93]

- In February 2018, a suspected poacher was killed and eaten by lions near Kruger National Park.[94][95]

- Towards the end of the same month, conservationist Kevin Richardson took three lions for a walk at Dinokeng Game Reserve, near Pretoria in South Africa. A lioness then pursued an impala for at least 2 km (1.2 mi), before unexpectedly killing a 22-year-old woman near her car.[96][97]

- In July 2018, a "loud commotion" coming from lions was heard by an anti-poaching dog in Sibuya Game Reserve near Kenton-on-Sea, South Africa. The next day, human remains were found in the lion enclosure. They were suspected to have been rhino-poachers, as they had equipment such as a high-powered rifle and wire cutters.[98][99]

Threats[edit]

In Africa, lions are threatened by pre-emptive killing or in retaliation for preying on livestock. Prey base depletion, loss and conversion of habitat have led to a number of subpopulations becoming small and isolated. Trophy hunting has contributed to population declines in Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Zambia.[7] Although lions and their prey are officially protected in Tsavo National Parks, they are regularly killed by local people, with over 100 known lion killings between 2001 and 2006.[72] Between 2008 and 2013, bones and body parts from at least 2621 individual lions were exported from South Africa to Southeast Asia, and another 3437 lion skeletons between 2014 and 2016. Lion bones are used to replace tiger bones in traditional Asian medicines.[100] Private game ranches in South Africa also breed lions for the canned hunting industry.[101] In 2014, seven lions in Ikona Wildlife Management Area were reportedly poisoned by a herdsman for attacking his cattle.[102] In February 2018, the carcasses of two male and four female lions were found dead in Ruaha National Park, and were suspected to have died of poisoning.[103][104] In 2015 and 2017, two male lions, Cecil and his son Xanda, were killed by trophy hunters in Zimbabwe's Hwange National Park.[105][106] In Zambia's Kafue National Park, uncontrolled bushfires and hunting of lions and prey species makes it difficult for the lion population to recover. Cub mortality in particular is high.[107]

Conservation[edit]

African lions are included in CITES Appendix II. Today, lion populations are stable only in large protected area complexes.[61] IUCN regional offices and many wildlife conservation organisations cooperated to develop a Lion Conservation Strategy for Eastern and Southern Africa in 2006. The strategy envisages to maintain sufficient habitat, ensure a sufficient wild prey base, make lion-human coexistence sustainable and reduce factors that lead to further fragmentation of populations.[4] A significant incentive for local communities in a number of Southern African countries to support measures for conservation is that they generate significant revenue through wildlife tourism.[7] In 2010, the small and isolated Kalahari population was estimated at 683 to 1,397 individuals in three protected areas, the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, the Kalahari Gemsbok and Gemsbok National Parks.[108] More than 2000 lions exist in the well-protected Kruger National Park.[109] In June 2015, seven lions were relocated from KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa to Akagera National Park in Rwanda.[110]

In captivity[edit]

At the beginning of the 21st century, the Addis Ababa Zoo kept 16 adult lions. It is assumed that their ancestors, five males and two females, were caught in southwestern Ethiopia as part of a zoological collection for Emperor Haile Selassie I.[36][111] In 2006, the registry of the International Species Information System (ISIS) showed 29 lions that were derived from animals captured in Angola and Zimbabwe. In addition, about 100 captive lions were registered as P. l. krugeri by ISIS, which derived from lions captured in South Africa.[6][12] Interest in the Cape lion had led to attempts to conserve possible descendants in places like Tygerberg Zoo.[112][113]

Regional names[edit]

Lion populations in Southern and East Africa were referred to by several regional names, including "Katanga lion", "Transvaal lion", "Kalahari lion",[14][17][18] "Southeast African lion", and "Southwest African lion",[114] "Masai lion", "Serengeti lion,"[78] "Tsavo lion"[47] and "Uganda lion".[22]

Cultural significance[edit]

The lion is featured as an animal symbol in East Africa.[115][116] The name 'Simba' is a Swahili word for the lion, which also means 'aggressive', 'king' and 'strong'.[52]

Gallery[edit]

-

Lioness in Etosha National Park

-

Male at Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, South Africa

-

Lioness at Phinda Private Game Reserve

-

Female in Hlane Royal National Park, Eswatini

-

Lion pair at Selous Game Reserve, Tanzania

-

A male in Murchison Falls National Park, Uganda

See also[edit]

- Lions: Barbary lion · West African lion · Central African lion clade · Asiatic lion · History of lions in Europe

- Wild cats in Africa: African leopard · African golden cat · Caracal · Serval · African wildcat · Sand cat · Cheetah

- Elsa the lioness

- Born Free

- The Lion King

- African Cats

- Ewaso Lions

- Maasai people

- Wildlife of South Africa

- Bloemfontein lion

- American lion

- Physical comparison of tigers and lions

- Tiger versus lion

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Panthera leo". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b Wood, John George (1865). "Felidæ; or the Cat Tribe". The illustrated natural history. Boradway, Ludgate Hill, New York City: Routledge. p. 147.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Wood, John George (1865). "Felidæ; or the Cat Tribe". Animal Kingdom. Boston: H. A. Brown. p. 147.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bauer, H.; Chardonnet, P.; Nowell, K. (December 2005), Status and distribution of the lion (Panthera leo) in East and Southern Africa (PDF), Johannesburg, South Africa: East and Southern African lion Conservation Workshop, retrieved 2018-09-03

- ^ a b c Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11). ISSN 1027-2992.

- ^ a b c d Barnett, R.; Yamaguchi, N.; Barnes, I.; Cooper, A. (2006). "Lost populations and preserving genetic diversity in the lion Panthera leo: Implications for its ex situ conservation" (PDF). Conservation Genetics. 7 (4): 507–514. doi:10.1007/s10592-005-9062-0. S2CID 24190889. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-08-24.

- ^ a b c d e f IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017-3. 2016. 2016. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T15951A107265605.en https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/15951/107265605.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|assessor2=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|assessor3=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|assessor4=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|assessor5=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|assessor=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|taxon=ignored (help) - ^ Bauer, H.; Chapron, G.; Nowell, K.; Henschel, P.; Funston, P.; Hunter, L. T.; Macdonald, D. W.; Packer, C. (2015). "Lion (Panthera leo) populations are declining rapidly across Africa, except in intensively managed areas". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (48): 14894–14899. doi:10.1073/pnas.1500664112. PMC 4672814. PMID 26504235.

- ^ a b c d e f Mazak, V. (1975). "Notes on the Black-maned Lion of the Cape, Panthera leo melanochaita (Ch. H. Smith, 1842) and a Revised List of the Preserved Specimens". Verhandelingen Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen (64): 1–44.

- ^ a b Smith, C.H. (1842). "Black maned lion Leo melanochaitus". In Jardine, W. (ed.). The Naturalist's Library. Vol. 15 Mammalia. London: Chatto and Windus. p. Plate X, 177.

- ^ Noack, T. (1891). "Felis leo". Jahrbuch der Hamburgischen Wissenschaftlichen Anstalten. 9 (1): 120.

- ^ a b c d Neumann, O. (1900). "Die von mir in den Jahren 1892–95 in Ost- und Central-Afrika, speciell in den Massai-Ländern und den Ländern am Victoria Nyansa gesammelten und beobachteten Säugethiere". Zoologische Jahrbücher. Abtheilung für Systematik, Geographie und Biologie der Thiere. 13 (VI): 529–562.

- ^ Lönnberg, E. (1910). "Mammals". In Sjöstedt, Y. (ed.). Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Schwedischen Zoologischen Expedition nach dem Kilimandjaro, dem Meru und den umgebenden Massaisteppen Deutsch-Ostafrikas 1905–1906. Volume 1. Uppsala: Königlich Schwedische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- ^ a b c Lönnberg, E. (1914). "New and rare mammals from Congo". Revue de Zoologie Africaine (3): 273–278.

- ^ a b c Heller, E. (1914). "New races of carnivores and baboons from equatorial Africa and Abyssinia". Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 61 (19): 1–12.

- ^ Allen, J. A. (1924). "Carnivora Collected By The American Museum Congo Expedition". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 47: 73–281.

- ^ a b c Roberts, A. (1929). "New forms of African mammals". Annals of the Transvaal Museum. 21 (13): 82–121.

- ^ a b Roberts, A. (1948). "Descriptions of some new subspecies of mammals". Annals of the Transvaal Museum. 21 (1): 63–69.

- ^ Zukowsky, L. (1964). "Eine neue Löwenrasse als weiterer Beleg für die Verzwergung der Wirbeltierfauna des afrikanischen Osthorns". Milu, Wissenschaftliche und Kulturelle Mitteilungen aus dem Tierpark Berlin (1): 269–273.

- ^ a b c Allen, G. M. (1939). A Checklist of African Mammals. Vol. 83. pp. 1–763.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Lundholm, B. (1952). "A skull of a Cape lioness (Felis leo melanochaitus H. Smith". Annals of the Transvaal Museum (32): 21–24.

- ^ a b c d e f Hemmer, H. (1974). "Untersuchungen zur Stammesgeschichte der Pantherkatzen (Pantherinae) Teil 3. Zur Artgeschichte des Löwen Panthera (Panthera) leo (Linnaeus, 1758)". Veröffentlichungen der Zoologischen Staatssammlung. 17: 167–280.

- ^ Stevenson-Hamilton, J. (1954). "Specimen of the extinct Cape lion". African Wildlife (8): 187–189.

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (1930). "The lions of Asia". Journal of the Bombay Natural Historical Society. 34: 638–665.

- ^ Ellerman, J. R.; Morrison-Scott, T. C. S. (1966). "Subgenus Leo Oken, 1816, (Brehm, 1829)". Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian Mammals 1758 to 1946 (Second ed.). London: British Museum (Natural History). p. 319.

- ^ Meester, J.; Setzer, H. W. (1977). The mammals of Africa. An identification manual. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- ^ Yamaguchi, N. (2000). "The Barbary lion and the Cape lion: their phylogenetic places and conservation" (PDF). African Lion Working Group News. 1: 9–11.

- ^ O’Brien, S. J.; Martenson, J. S.; Packer, C.; Herbst, L.; de Vos, V.; Joslin, P.; Ott-Joslin, J.; Wildt, D. E. & Bush, M. (1987). "Biochemical genetic variation in geographic isolates of African and Asiatic lions" (PDF). National Geographic Research. 3 (1): 114–124. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-02.

- ^ a b c Antunes, A.; Troyer, J. L.; Roelke, M. E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Packer, C.; Winterbach, C.; Winterbach, H.; Johnson, W. E. (2008). "The Evolutionary Dynamics of the Lion Panthera leo Revealed by Host and Viral Population Genomics". PLOS Genetics. 4 (11): e1000251. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000251. PMC 2572142. PMID 18989457.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Mazák, J. H. (2010). "Geographical variation and phylogenetics of modern lions based on craniometric data". Journal of Zoology. 281 (3): 194−209. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00694.x.

- ^ Bertola, L. D.; Van Hooft, W. F.; Vrieling, K.; Uit De Weerd, D. R.; York, D. S.; Bauer, H.; Prins, H. H. T.; Funston, P. J.; Udo De Haes, H. A.; Leirs, H.; Van Haeringen, W. A.; Sogbohossou, E.; Tumenta, P. N.; De Iongh, H. H. (2011). "Genetic diversity, evolutionary history and implications for conservation of the lion (Panthera leo) in West and Central Africa" (PDF). Journal of Biogeography. 38 (7): 1356–1367. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02500.x. S2CID 82728679.

- ^ a b Bertola, L.D.; Jongbloed, H.; Van Der Gaag, K.J.; De Knijff, P.; Yamaguchi, N.; Hooghiemstra, H.; Bauer, H.; Henschel, P.; White, P.A.; Driscoll, C.A. & Tende, T. (2016). "Phylogeographic patterns in Africa and High Resolution Delineation of genetic clades in the Lion (Panthera leo)". Scientific Reports. 6: 30807. Bibcode:2016NatSR...630807B. doi:10.1038/srep30807. PMC 4973251. PMID 27488946.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bertola, L.D.; Jongbloed, H.; Van Der Gaag K.J.; De Knijff, P.; Yamaguchi, N.; Hooghiemstra, H.; Bauer, H.; Henschel, P.; White, P.A.; Driscoll, C.A.; Tende, T.; Ottosson, U.; Saidu, Y.; Vrieling, K.; De Iongh, H. H. (2016). "Phylogeographic patterns in Africa and High Resolution Delineation of genetic clades in the Lion (Panthera leo)". Scientific Reports. 6: 30807. Bibcode:2016NatSR...630807B. doi:10.1038/srep30807. PMC 4973251. PMID 27488946.

- ^ Dubach, J.; Patterson, B. D.; Briggs, M. B.; Venzke, K.; Flamand, J.; Stander, P.; Scheepers, L.; Kays, R. W. (2005). "Molecular genetic variation across the southern and eastern geographic ranges of the African lion, Panthera leo". Conservation Genetics. 6 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1007/s10592-004-7729-6. S2CID 30414547.

- ^ Bertola, L. D.; Van Hooft, W. F.; Vrieling, K.; Uit De Weerd, D. R.; York, D. S.; Bauer, H.; Prins, H. H. T.; Funston, P. J.; Udo De Haes, H. A.; Leirs, H.; Van Haeringen, W. A.; Sogbohossou, E.; Tumenta, P. N.; De Iongh, H. H. (2011). "Genetic diversity, evolutionary history and implications for conservation of the lion (Panthera leo) in West and Central Africa". Journal of Biogeography. 38 (7): 1356–1367. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02500.x. S2CID 82728679.

- ^ a b c Bruche, S.; Gusset, M.; Lippold, S.; Barnett, R.; Eulenberger, K.; Junhold, J.; Driscoll, C. A.; Hofreiter, M. (2012). "A genetically distinct lion (Panthera leo) population from Ethiopia". European Journal of Wildlife Research. 59 (2): 215–225. doi:10.1007/s10344-012-0668-5. S2CID 508478.

- ^ a b Barnett, R.; Sinding, M. H.; Vieira, F. G.; Mendoza, M. L.; Bonnet, M.; Araldi, A.; Kienast, I.; Zambarda, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Henschel, P.; Gilbert, M. T. (2018). "No longer locally extinct? Tracing the origins of a lion (Panthera leo) living in Gabon". Conservation Genetics. 19 (3): 1–8. doi:10.1007/s10592-017-1039-2. PMC 6448349. PMID 31007636.

- ^ a b Guggisberg, C. A. W. (1975). "Lion Panthera leo (Linnaeus, 1758)". Wild Cats of the World. New York: Taplinger Publishing. pp. 138–179. ISBN 978-0-8008-8324-9.

- ^ Smithers, R. H. N. (1971). The Mammals of Botswana. Pretoria: University of Pretoria.

- ^ a b West, P. M.; Packer, C. (2002). "Sexual Selection, Temperature, and the Lion's Mane". Science. 297 (5585): 1339–1943. Bibcode:2002Sci...297.1339W. doi:10.1126/science.1073257. PMID 12193785. S2CID 15893512.

- ^ a b Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. (1996). "African lion" (PDF). Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 17–21. ISBN 978-2-8317-0045-8.

- ^ Smuts, G. L.; Robinson, G. A.; Whyte, I. J. (1980). "Comparative growth of wild male and female lions (Panthera leo)". Journal of Zoology. 190 (3): 365–373. Bibcode:2010JZoo..281..263G. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1980.tb01433.x.

- ^ a b Turner, J. A.; Vasicek, C. A.; Somers, M. J. (2015). "Effects of a colour variant on hunting ability: the white lion in South Africa". Open Science Repository Biology: e45011830.

- ^ a b Guggisberg, Charles Albert Walter (1963). Simba: The Life of the Lion. Philadelphia, PA: Chilton Books. ASIN B000OKBJQ0.

- ^ Gnoske T. P.; Celesia, G. G.; Kerbis, Peterhans J. C. (2006). "Dissociation between mane development and sexual maturity in lions (Panthera leo): solution to the Tsavo riddle?". Journal of Zoology. 270 (4): 551–560. Bibcode:2010JZoo..281..263G. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00200.x.

- ^ Call the Hair Club for Lions. The Field Museum.

- ^ a b Borzo, G. (2002). "Unique social system found in famous Tsavo lions". EurekAlert.

- ^ Nagel, D.; Hilsberg, S.; Benesch, A.; Scholtz, J. (2003). "Functional morphology and fur patterns in recent and fossil Panthera species". Scripta Geologica. 126: 227–239.

- ^ McBride, C. (1977). The White Lions of Timbavati. Johannesburg: E. Stanton. ISBN 978-0-949997-32-6.

- ^ Tucker, L. (2003). Mystery of the White Lions—Children of the Sun God. Mapumalanga: Npenvu Press. ISBN 978-0-620-31409-1.

- ^ Wood, G. L. (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Sterling Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ a b Brakefield, T. (1993). Big Cats: Kingdom of Might. Voyageur Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-89658-329-0.

- ^ a b c Mésochina, P.; Mbangwa, O.; Chardonnet, P.; Mosha, R.; Mtui, B.; Drouet, N.; Kissui, B. (2010), "Conservation status of the lion (Panthera leo Linnaeus, 1758) in Tanzania", SCI Foundation, MNRT-WD, TAWISA & IGF Foundation, Paris

- ^ Funaioli, U. and Simonetta, A. M. (1966). "The Mammalian Fauna of the Somali Republic: Status and Conservation Problems". Monitore Zoologico Italiano, Supplemento. 1 (1): 285–347. doi:10.1080/03749444.1966.10736746.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Chardonnet, P. (2002). "Chapter II: Population Survey". Conservation of the African Lion : Contribution to a Status Survey (PDF). Paris: International Foundation for the Conservation of Wildlife, France & Conservation Force, USA. pp. 21–101. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2013.

- ^ a b Fagotto, F. (1985). "Larger animals of Somalia in 1984". Environmental Conservation. 12 (3): 260−264. doi:10.1017/S0376892900016015. S2CID 86042501.

- ^ Treves, A.; Naughton-Treves, L. (1999). "Risk and opportunity for humans coexisting with large carnivores". Journal of Human Evolution. 36 (3): 275−282. doi:10.1006/jhev.1998.0268. PMID 10074384.

- ^ Smithers, R.H.N. (1971). The Mammals of Botswana. Pretoria: University of Pretoria.

- ^ Stander, P.E. (1990). "A suggested management strategy for stock-raiding lions in Namibia". South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 20 (2): 37−43.

- ^ Rautenbach, I. L. (1978). The Mammals of the Transvaal. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb Riggio, J.; Jacobson, A.; Dollar, L.; Bauer, H.; Becker, M.; Dickman, A.; Funston, P.; Groom, R.; Henschel, P.; De Iongh, H.; Lichtenfeld, L. (2013). "The size of savannah Africa: a lion's (Panthera leo) view". Biodiversity and Conservation. 22 (1): 17–35. doi:10.1007/s10531-012-0381-4. S2CID 18891375.

- ^ a b Treves, A.; Plumptre, A. J.; Hunter, L. T. B.; Ziwa, J. (2009). "Identifying a potential lion Panthera leo stronghold in Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda, and Parc National des Virunga, Democratic Republic of Congo". Oryx. 43: 60−66. doi:10.1017/S003060530700124X. S2CID 73692646.

- ^ Mudumba, T.; Mulondo, P.; Okot, E.; Nsubuga, M.; Plumptre, A. (2010), "National census of lions and hyaenas in Uganda", Uganda Wildlife Authority, Uganda

- ^ a b c d Chardonnet, P.; Mésochina, P.; Bento, C.; Conjo, D.; Begg, C. l. (2009), Conservation status of the lion (Panthera leo Linnaeus, 1758) in Mozambique, Maputo, Mozambique

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Lions rediscovered in Ethiopia's Alatash National Park". BBC News. 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ Howard, B. C. (2016). "Once Thought Extinct, 'Lost' Group of Lions Discovered in Africa". National Geographic. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- ^ Wong, S. (2016). "Hidden population of up to 200 lions found in remote Ethiopia". New Scientist. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d Bauer, H.; Van Der Merwe, S. (2004). "Inventory of free-ranging lions Panthera leo in Africa". Oryx. 38 (1): 26–31. doi:10.1017/S0030605304000055. S2CID 86796885.

- ^ Yirga, G.; Gebresenbet, F.; Deckers, J.; Bauer, H. (2014). "Status of Lion (Panthera leo) and Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta) in Nechisar National Park, Ethiopia". Momona Ethiopian Journal of Science. 6 (2): 127–137. doi:10.4314/mejs.v6i2.109714.

- ^ a b Dolrenry S.; Hazzah L.; Frank L. G. (2016). "Conservation and monitoring of a persecuted African lion population by Maasai warriors". Conservation Biology. 30 (3): 467–475. doi:10.1111/cobi.12703. PMID 27111059. S2CID 3780510.

- ^ Omoya, E. O.; Mudumba, T.; Buckland, S. T.; Mulondo, P. & Plumptre, A. J. (2014). "Estimating population sizes of lions Panthera leo and spotted hyaenas Crocuta crocuta in Uganda's savannah parks, using lure count methods" (PDF). Oryx. 48 (3): 394–401. doi:10.1017/S0030605313000112. S2CID 208525344.

- ^ a b Frank, L.; Maclennan, S.; Hazzah, L.; Hill, T.; Bonham, R. (2006), "Lion Killing in the Amboseli-Tsavo Ecosystem, 2001–2006, and its Implications for Kenya's Lion Population" (PDF), Living with Lions, Nairobi, Kenya 9

- ^ Hayward, M. W.; Adendorff, J.; O’Brien, J.; Sholto-Douglas, A.; Bissett, C.; Moolman, L. C.; Bean, P.; Fogarty, A.; Howarth, D.; Slater, R.; Kerley, G. I. (2007). "Practical considerations for the reintroduction of large, terrestrial, mammalian predators based on reintroductions to South Africa's Eastern Cape Province". The Open Conservation Biology Journal. 1 (1): 1–11. doi:10.2174/1874839200701010001.

- ^ Cushman, S. A.; Elliot, N. B.; Bauer, D.; Kesch, K.; Bothwell, H.; Flyman, M.; Mtare, G.; Macdonald, D. W.; Loveridge, A. J. (2018). "Prioritizing core areas, corridors and conflict hotspots for lion conservation in southern Africa". PLOS ONE. 13 (7): e0196213. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0196213. PMC 6033387. PMID 29975694.

- ^ Henschel, P. H.; Azani, D. E.; Burton, C. O.; Malanda, G.; Saidu, Y. O.; Sam, M. O.; Hunter, L. U. (2010). "Lion status updates from five range countries in West and Central Africa". Cat News. 52: 34–39.

- ^ Hedwig, D.; Kienast, I.; Bonnet, M.; Curran, B. K.; Courage, A.; Boesch, C.; Kühl, H. S.; King, T. (2017). "A camera trap assessment of the forest mammal community within the transitional savannah‐forest mosaic of the Batéké Plateau National Park, Gabon". African Journal of Ecology. 56 (4): 777–790. doi:10.1111/aje.12497.

- ^ Henschel, P.; Malanda, G. A.; Hunter, L. (2014). "The status of savanna carnivores in the Odzala-Kokoua National Park, northern Republic of Congo". Journal of Mammalogy. 95 (4): 882−892. Bibcode:2007JMamm..88..275L. doi:10.1644/13-mamm-a-306. ISSN 0022-2372. S2CID 84403126.

- ^ a b c d Schaller, George B. (1972). The Serengeti lion: A study of predator–prey relations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73639-6.

- ^ Milius, S. (2002). "Biology: Maneless lions live one guy per pride". Society for Science & the Public. 161 (16): 253. doi:10.1002/scin.5591611614.

- ^ a b Sinclair, A. R. E.; Norton-Griffiths, M., ed. (1979). "Population changes in lions and other predators". Serengeti: dynamics of an ecosystem. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 249–262.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Bertram, B. C. R. (1973). "Lion population regulation". East Africa Wildlife Journal. 11 (3–4): 215−225. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1973.tb00088.x.

- ^ Borrego, N.; Ozgul, A.; Slotow, R.; Packer, C. (2018). "Lion population dynamics: do nomadic males matter?". Behavioral Ecology. 29 (3): 660–666. doi:10.1093/beheco/ary018.

- ^ Elliot, N. B.; Cushman, S. A.; Macdonald, D. W.; Loveridge, A. J. (2014). "The devil is in the dispersers: predictions of landscape connectivity change with demography". Journal of Applied Ecology. 51 (5): 1169–1178. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12282.

- ^ Hayward, M. W.; Kerley, G. I. H. (2005). "Prey preferences of the lion (Panthera leo)" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 267 (3): 309–322. Bibcode:2010JZoo..281..263G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.611.8271. doi:10.1017/S0952836905007508.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Schaller72was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Davidson, Z., Valeix, M., Van Kesteren, F., Loveridge, A.J., Hunt, J.E., Murindagomo, F. and Macdonald, D.W. (2013). "Seasonal diet and prey preference of the African lion in a waterhole-driven semi-arid savanna". PLOS ONE. 8 (2): e55182. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055182.g001. PMC 3566210. PMID 23405121.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Joubert, D. (2006). "Hunting behaviour of lions (Panthera leo) on elephants (Loxodonta africana) in the Chobe National Park, Botswana". African Journal of Ecology. 44 (2): 279–281. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2006.00626.x.

- ^ Power, R. J.; Compion, R. X. S. (2009). "Lion predation on elephants in the Savuti, Chobe National Park, Botswana". African Zoology. 44 (1): 36–44. doi:10.3377/004.044.0104. S2CID 86371484.

- ^ Jeal, Tim (2013). Livingstone: Revised and Expanded Edition. Yale University Press. p. 59.

- ^ Kerbis Peterhans, J.C. and Gnoske, T.P. (2001). "The Science of 'Man-Eating*' Among Lions Panthera leo With a Reconstruction of the Natural History of the 'Man-Eaters of Tsavo'". Journal of East African Natural History. 90 (1): 1–40. doi:10.2982/0012-8317(2001)90[1:TSOMAL]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85985722.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Field Museum uncovers evidence behind man-eating; revises legend of its infamous man-eating lions" (Press release). The Field Museum. 2003.

- ^ Patterson, John H. (1907). The man-eaters of Tsavo and other East African adventures. London: Macmillan and Co.

- ^ Rushby, George G. (1965). No More the Tusker. London: W. H. Allen.

- ^ "South African lions eat 'poacher', leaving just his head". The BBC. 2018-02-14. Retrieved 2018-02-25.

- ^ Haden, A. (2018-02-12). "Suspected poacher mauled to death by lions close to Kruger National Park". The South African. Retrieved 2018-02-25.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Torchia, C. (2018-02-28). "Lion kills woman at refuge of South African 'lion whisperer'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- ^ Feingold, S. (2018-03-02). "Lion mauls woman to death at popular South African wildlife sanctuary". CNN. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- ^ "Lions eat 'rhino poachers' on South African game reserve". BBC. 2018-07-05. Retrieved 2018-07-19.

- ^ "Suspected rhino poachers killed by lions in South Africa". Ottawa Citizen. Associated Press. 2018-07-06. Retrieved 2018-07-19.

- ^ Williams, V. L.; Loveridge, A. J.; Newton, D. J.; Macdonald, D. W. (2017). "A roaring trade? The legal trade in Panthera leo bones from Africa to East-Southeast Asia". PLOS ONE. 12 (10): e0185996. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1285996W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185996. PMC 5655489. PMID 29065143.

- ^ Schroeder, R. A. (2018). "Moving Targets: The 'Canned'Hunting of Captive-Bred Lions in South Africa". African Studies Review. 61 (1): 8–32. doi:10.1017/asr.2017.94. S2CID 150275315.

- ^ "'Herdsmen' poison lions, vultures — but not in Nigeria". The Cable. 2018-02-17. Retrieved 2018-02-24.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Kamoga, J. (2018). "East African lions dying of poisoning". The Observer. Retrieved 2018-02-24.

- ^ Winter, S. (2018-02-16). "Lion MASSACRE as six big cats die after eating 'poison'". The Express. Retrieved 2018-02-24.

- ^ "Zimbabwe's 'iconic' lion Cecil killed by hunter". BBC News. 27 July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 July 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "Xanda, son of Cecil the lion, killed by hunter in Zimbabwe". BBC News. 20 July 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ^ Midlane, N. (2013). The conservation status and dynamics of a protected African lion Panthera leo population in Kafue National Park, Zambia. Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

- ^ Ferreira, S. M.; Govender, D.; Herbst, M. (2013). "Conservation implications of Kalahari lion population dynamics". African Journal of Ecology. 51 (2): 176–179. doi:10.1111/aje.12003.

- ^ The Kruger Nationalpark Map. Honeyguide Publications CC. South Africa 2004.

- ^ Smith, D. (2015). "Lions to be reintroduced to Rwanda after 15-year absence following genocide". The Guardian.

- ^ Tefera, M. (2003). "Phenotypic and reproductive characteristics of lions (Panthera leo) at Addis Ababa Zoo". Biodiversity & Conservation. 12 (8): 1629–1639. doi:10.1023/A:1023641629538. S2CID 24543070.

- ^ "South Africa: Lion Cubs Thought to Be Cape Lions". AP Archive, of the Associated Press. 8 November 2000. (with 2-minute video of cubs at zoo with John Spence, 3 sound-bites, and 15 photos)

- ^ "'Extinct' lions (Cape lion) surface in Siberia". The BBC. 2000-11-05. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ Jackson, D. (2010). "Introduction". Lion. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-1861897350.

- ^ Hogarth, C.; Butler, N. (2004). "Animal Symbolism (Africa)". In Walter, M. N. (ed.). Shamanism: An Encyclopedia of World Beliefs, Practices, and Culture, Volume 1. pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-1-57607-645-3.

- ^ Lynch, P. A. (2004). African Mythology A to Z. Infobase Publishing. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8160-4892-2.

Further reading[edit]

- Kays, Roland W.; Patterson, Bruce D. (2002). "Mane variation in African lions and its social correlates". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 80 (3): 471–478. doi:10.1139/z02-024. ISSN 0008-4301.

- Selous, F. C. (2011). "XXV". Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 445. ISBN 978-1108031165.

- Beolens, B.; Watkins, M.; Grayson, M. (2009-10-07). The Eponym Dictionary of Mammals. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-8018-9533-3.

- Schofield, A. (2013). White Lion: Back to the Wild. Pennsauken: BookBaby. ISBN 978-0620570053.

External links[edit]

- $0.5m funding to stop the decline in the population of African lions

- What Will It Take to Save the East African Lion from Extinction? Hunting or Herding?

- Lions in East Africa

- East African lion shot by Theodore Roosevelt

- Two marauding lions at Issuna, Tanzania

- Giant Lions Once Prowled East Africa, 200,000-Year-Old Skull Reveals

- Kali the Masai lion

- Notch the Masai lion

- BBC Earth: Lions take down an adult elephant

- The Savuti Lions of the Chobe National Park

- Holding the line for lions in Mozambique (including in Gorongosa National Park)

- A Zambian lion stirs

- Nakawa and Lady Liuwa the Zambian lions

- Recovering population of Zimbabwean African lions show low genetic diversity

- Shamba the South African lion

- Angola lion

- What Happened to Angola’s 1,000 Lions?

- Death of a lion that traveled almost 1,300 km (810 mi) between Angola and Namibia

- Kebbel the Namibian lion at Sesfontein Conservancy

- Lobengula the South African guardian lion

- iNaturalist: Southern Lion (Panthera leo ssp. melanochaita)

- Known for escapes, South African lion becomes a father