User:ODavies 1/sandbox

Introduction[edit]

The Foreign Language Effect (FLE) is the impact that operating in one’s second language (L2) has on the thoughts of the user and that of a native (L1) listener. The scientific underpinning of this idea is the hypothesis of Linguistic Relativity. This is the notion that the language we speak impacts the thoughts we think. It is a neuroscience-driven modernisation of the Weak Sapir-Whorf hypothesis [2], posthumously developed from the work of Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf. The term FLE was first coined by Boaz Keysar in 2012 [3] as part of an empirical research paper, describing the lowered emotional content of L2 and its impact on decision making. In a nutshell, the FLE states that when an individual seeks to extract meaning from language in L2 (known as semantic integration), they are less susceptible to the emotional content of the information presented [4] and are less likely to make emotional decisions. However, when an L2 speaker is addressing an L1 listener there may be grounds to believe that they are considered less believable.[5]

The Science of Language Interpretation[edit]

Semantic Integration[edit]

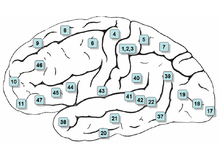

Semantic information refers to information that we might derive meaning from. When information is received in the form of language (written or verbal), the brain must undergo a process known as semantic integration where the information delivered is processed and meaning is derived. This occurs in Wernicke's Area, located in the posterior third of the Superior Temporal Gyrus of the Temporal Lobe of the brain. It is most commonly found in the left hemisphere of the brain and named after Carl Wernicke.

Increased Semantic Integration Demands in Foreign Languages[edit]

Reading in L2[edit]

When language is read in L2, it is initially processed in the Occipital Lobe of the brain, specifically the Primary Visual Cortex. Eventually, it undergoes a ‘recognition’ phase, occurring in the Visual Association Cortex (Brodmann’s Area 19) where the information is associated to personal experience. In L2, it is hypothesised that words have less emotional valence as they are commonly learnt in a classroom environment, so there are less emotionally salient personal experiences to relate to words, resulting in more rational[6] decision making [7].

Hearing L2 Accented Information[edit]

When language is delivered verbally, it is processed in the Primary Auditory Cortex, located in the Temporal Lobe. It must also undergo a recognition phase. However, if the information is delivered with an unfamiliar accent e.g. L1 accent on L2 speech delivered to an L1 listener, the phonology (sounds making up words) will prove less familiar. This may result in increased semantic integration demands. This is hypothesised to impact the believability of information, though research in this area is ongoing.

Cognitive Load[edit]

Both of these effects of L2 operation have been identified as increasing the semantic integration demand, coined an increased ‘cognitive load’ by Keysar. This has been associated with impacts on higher level thought processes.

Research Methods[edit]

As well as the use of behavioural methods such as responses to relevant tasks and Reaction Times, Event-Related Potentials are often used when exploring Linguistic Relativity and the Foreign Language Effect. Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) have been used to assess the impact of L2 operation on cognition. Examples include:

- The co-activation of L1 during L2

- The impact of emotionally negative words when operating in L2

- The believability of L1 accented information delivered in L2 to an L1 listener

ERPs are pre-conscious recordings of brain activity in response to a specific event, gathered using Electroencephalography(EEG). In the context of the examples in this article, the N400 Wave of ERPs is used. This is a wave generated 400 milliseconds after event-onset and has been shown to represent semantic integration demands [8] as well as information believability. It is an useful research method because it tells us what we think without the inconsistencies that self-reporting may present. Specifically, the use of ERPs to explore the believability of foreign accented information would be useful.

Empirical Evidence[edit]

Studies into bilingual participants were initially conducted as direct evidence for the influence of language on thought (Linguistic Relativity). Specifically, one study displayed that an individual’s first language is unconsciously activated even when they’re using their second language [9]. However, Jończyk displayed that this effect did not apply to emotionally negative terms such as ‘torture’, ‘war’ and ‘failure’. Keysar was the first person to define this effect as The Foreign Language Effect and explore its impact on behaviour. By presenting participants with the “Asian Disease” problem and monitoring the choices they made when it was presented in L1 and L2.

The Asian Disease problem frames information as a gain or a loss. It is well documented that information framed as a gain makes us risk averse (more likely to choose option 1 from gain-frame column) whereas information framed as a loss makes us risk seeking (more likely to choose option 2 from loss-frame column)[10].

However, Keysar identified that participant decision making was not impacted by the framing effect when it was presented in L2. The experiment compared English-Japanese, English-Korean and English-French bilinguals. The study concluded that individuals are less likely to make emotional decision in L2. This was attributed to L2 being less bound by emotion as it is normally learnt in a classroom setting. Additionally, the increased cognitive load in L2 suggested individuals would be more likely to rely on semantic processes than any associated emotion.

| Gain-Frame | Loss-Frame |

|---|---|

| 1. If you choose Medicine A, 200,000 people will be saved. | 1. If you choose Medicine A, 400,000 will die. |

| 2. If you choose Medicine B, there is a 33.3% chance that 600,000 people will be saved and a 66.6% chance that no one will be saved. | 2. If you choose Medicine B, there is a 33.3% chance that no one will die and a 66.6% chance that 600,000 people will die. |

Limits to the Foreign Language Effect[edit]

Most studies into the FLE have considered late-L2 bilinguals. This means participants had learnt their second language during adulthood. As a result, there will be an increased effect of L1 accent, reduced fluency and increased cognitive load. For the most part, empirical research has not focused on early-L2 bilinguals as well as instances where L2 fluency has exceeded L1 fluency. However, some studies have explored the limits of the FLE, specifically showing no FLE in relation to the Asian Disease problem in linguistically similar languages (Norwegian and Swedish) [11]. Additionally, the same study showed there was no FLE in Swedish-English bilinguals whom had strong fluency in their L2 (English). This was thought to be because Sweden is often culturally exposed to English through media sources which frequently seek to elicit emotional responses. Hence, questions have been posed as to the extent of the FLE in a globalised world.

References[edit]

- ^ https://scholar.harvard.edu/pierredegalbert/node/632263

- ^ "Sapir Whorf Hypothesis". International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences: 13486–13490. 2001. doi:10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/03042-4.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "Why Don't We Believe Non-Native Speakers? The Influence of Accent on Credibility". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 46 (6): 1093–1096. 2010. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2010.05.025.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "The bilingual brain turns a blind eye to negative statements in the second language". Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioural Neuroscience. 16 (3): 527–540. 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "Why Don't We Believe Non-Native Speakers? The Influence of Accent on Credibility". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 46 (6): 1093–1096. 2010. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2010.05.025.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "It's (not) all Greek to me: Boundaries of the foreign language effect". Cognition. 196: 104148. 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "The Foreign-Language Effect: Thinking in a Foreign Tongue Reduces Decision Biases". Psychological Science. 23 (6): 661–668. 2012. doi:10.1177/0956797611432178.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "Thirty years and counting: finding meaning in the N400 component of the event-related brain potential (ERP)". Annual Review of Psychology. 62: 621–647. 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "Brain potentials reveal unconscious translation during foreign-language comprehension". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (30): 12530–12535. 2007. doi:10.1073/pnas.0609927104.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ ""The Framing of decisions and the psychology of choice"". Science. 221 (4481): 453–458. 1981. doi:10.1126/science.7455683.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "It's (not) all Greek to me: Boundaries of the foreign language effect". Cognition. 196: 104148. 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help)

Category:Neurolinguistics Category:Psycholinguistics Category:Linguistic theories and hypotheses Category:Multilingualism