User:Marc Dowling/Catacombs of Paris

| |

| |

| Collections | Carrières souterraines de Paris de la fin du XVIIIe siècle |

|---|---|

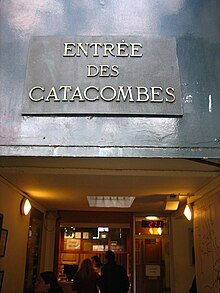

Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox Catégorie:Article utilisant l'infobox Musée Catégorie:Article utilisant une Infobox The Paris Catacombs (Listen) is the term used to name the municipal ossuary, originally part of the mines of Paris located in the 14th arrondissement of Paris, linked together by tunnels. They were turned into an ossuary at the end of the 18th century with the transfer of the remains of approximately six million people, evacuated from various Parisian cemeteries until 1861 for reasons of public health. They were then named "catacombs", because of the resemblance with the underground cemeteries of ancient Rome, although they were never officially used as burial grounds.

Approximately 1.7 km long and located twenty metres below the surface, the catacombs are visited by around 500,000 visitors a year (2015 figures) from the Place Denfert-Rochereau and a part of the Paris museum, the Carnavalet Museum. The part open to the public represents only a tiny fraction (about 0.5%) of the vast underground quarries, which stretch across several arrondissements of the capital. There are also other catacombs in Paris that are not accessible to the public.

Historical Context[edit]

Contexte : Underground Quarries of Paris[edit]

Nearly three hundred kilometres of catacombs run under Paris, sometimes spanning over three levels of quarries. The average depth is about twenty metres below ground level. When these quarries were in use, they were used to extract limestone, which for several centuries made it possible to construct the buildings of Paris without importing building materials.

There were also underground voids formed by the old gypsum quarries (at the foot of the Sacré-Cœur, for example). These voids have almost all been filled in or destroyed by lightning (quarry voluntarily collapsed by explosion of the pillars). Only the Buttes-Chaumont cave remains, which is actually part of an old underground quarry. The catacombs are mistakenly considered to make up all of the quarries in the capital, even though they only represent a tiny fraction.

At the end of the 18th century, in order to deal with the congestion of Parisian cemeteries and the growing sanitary problems, the decision was taken to move the bones to the quarries located outside the Barrière d'Enfer of the wall of the Ferme générale under la plain de Montsouris, which at the time, was in Montrouge.

The Cemeteries' Problems[edit]

The Holy Innocents’ Cemetery appeared in the 5th century around the church of Notre-Dame-des-Bois, a Merovingian place of worship. It was though to be destroyed during the Norman invasions of 885-886, it was replaced in the 11th century by Sainte-Opportune church, from then, the dead of several parishes on the right bank were buried there. In 1130, this cemetery took the name of Sainte-Innocents in reference to the "Holy Innocents” , children of Judea massacred under the orders of King Herod’s ; but this name also seems to have been a source of confusion from this time onwards with that of Saint-Innocent. This is following the burial of a child allegedly crucified by Jews in Pontoise around 1179, and after his burial in this place under the reign of Philippe-Auguste.[1]

Located between rue Saint-Denis, rue de la Ferronnerie, rue de la Lingerie and rue Berger, for thirteen centuries, dozens of generations of Parisians were buried, mainly those who had died in the city's twenty-two parishes, as well as the corpses evacuated from the Hôtel-Dieu and the morgue. From a small country cemetery, it became the largest cemetery in Paris, and was gradually surrounded by buildings until it became part of one of the city's busiest districts. Wars, epidemics and famines brought thousands of corpses to be buried here, in a small space, making it increasingly difficult to decompose them. The mass graves reached a depth of more than ten metres. By the end of the 18th century, the floor of the cemetery was more than two metres above street level, leading to long-standing sanitary problems.[2]

The constant decomposition of thousands of corpses spread disease. As early as 1554, doctors from the Faculty of Paris complained in vain about the risk of epidemics caused by the existence of the cemetery. In 1737, doctors from the Royal Academy of Sciences confirmed this, and the complaints from local residents continued to mount over the years. Although there were no more than two hundred individual burials per year, the mass graves, on the other hand, held up to fifteen hundred corpses. They were periodically emptied to make room for new graves, and the bones were placed in huge mass graves surrounding the cemetery. The last gravedigger, François Pourrain, estimates that he buried about ninety thousand corpses in the Holy Innocents’ Cemetery in under thirty years[3].

An eighteenth-century chronicler noted that in the neighbourhood, wine turns sour in less than a week and food spoils in a few days. The water in the wells was also contaminated by putrid matter, making it increasingly unfit for consumption. The situation even led Voltaire to criticise the religious authorities for persisting to bury the dead without concern for the health of the people. In 1765, a decree of the Parliament of Paris prohibited all burials within the city limits. Eight cemeteries were then created outside the walls of the capital, reviving Roman traditions. But tradition, the resistance of the religious authorities and popular piety prevented these practices from being quickly overcome[2].

The closure of the Holy Innocents' Cemetery[edit]

In early 1780, curious phenomena were reported in the surrounding cellars of the Holy Innocents' cemetery: the emissions from the decomposed corpses were so strong that it filtered through the walls and extinguished the tallow candles. It was then decided to coat the cellar walls in the district with lime. But on May 30th of the same year, a remarkable incident highlighted the seriousness of the problem and finally led to a decision: the wall of a cellar in the Rue de la Lingerie, adjacent to the cemetery, gave way under the pressure of the thousands of corpses in a mass grave.[2] Also, economic reasons sped up the decision to close the cemetery: the city lacked markets, the market at Les Halles had no room and rested against the cemetery wall. It was therefore an opportunity to redevelop the economic heart of the capital and reduce traffic congestion in an area that is busy during both day and night[3].

Antoine-Alexis Cadet de Vaux, sanitation inspector for the city of Paris, immediately had the cellar filled with quicklime and walled it in, ordering the cemetery to be closed forever. It was closed and access was forbidden to the public for five years, the cemetery was abandoned and fell into oblivion, which made it easier to move it, a few years later. Although burials were banned again in Paris, no solution was found for the emissions from the closed cemeteries[4].

In 1782, an anonymous project published in London was presented to the relevant authorities in Paris and ecclesiastics, which proposed a solution to the problem: inspired by ancient underground cemeteries, this project suggested taking advantage of the consolidations carried out over the last few years by the Inspection générale des carrières to set up an ossuary in a former underground quarry. The author details an idea: the author imagines coating the bodies with a kind of resin to slow down putrefaction and installing an embalming workshop or a drying room for corpses underground. The constant temperature in the basement would be used to preserve the bodies, which might be embalmed, a technique successfully used in the Capuchin catacombs of Palermo. In addition to the transfer of the bones, the author thought that the bodies could be stored directly underground after treatment, to save the families the expensive costs of a coffin and a tombstone. Finally, the health of the employees was also taken into account: he proposed covering the corpses with a thick layer of clay or bitumen to avoid an excessively mephitic atmosphere[5]. In 1782, the place was perhaps inappropriately given the name ‘catacombs’, as it was not really an underground cemetery with tombs and funerary monuments like the catacombs in Rome. By extension, the name catacombs came to refer, wrongly, to the galleries dug by the quarry inspection service to link all the quarries together, whereas their real name today is "service galleries established at the level of the former underground quarries of the city of Paris “ « galeries de servitude établies au niveau des anciennes carrières souterraines de la ville de Paris » [6].

After much debate, the project was finally approved. The police lieutenant, Lenoir, then considered transferring the bones contained in the Holy Innocents’ cemetery outside Paris. The development of the underground quarries of the Tombe-Issoire, located under the plain of Montrouge beyond the Barrière d'Enfer to the south of the capital, seemed to him to be perfectly suited for this purpose[5]. The city council and religious authorities decided to start the installations in 1785. In order not to offend the families who had graves in the Holy Innocents’ Cemetery, a reserved, walled area, known as the Clos de la Tombe-Issoire, was set up to display the elaborate tombstones and the most beautiful funerary monuments on the right bank. The land above the future ossuary has belonged since the to the community of St. John Lateran since the middle ages, which has a vault in its basement to house the bodies of the Templars [7].

A decree of the King's Council of 9 November 1785 decided to abolish the Holy Innocents’ cemetery with the evacuation of the bones, and then redeveloped it as a public market. The city of Paris then bought a former house of the Commandery of Saint-Jean-de-Latran, in what is now Rue Dareau, then located in Montrouge, under which an underground enclosure of 11,000 m2 was created, with meanders that extend for nearly 1,500 m under the space between the current Rue Dareau, Rue d'Alembert, Rue Hallé and the Parc Montsouris.

The name of catacombs is given to the quarries that were built, because of the similarities with the ancient underground cemeteries of Rome, even though the places were never used for direct burial and have no sacred significance. Throughout its existence, more than two million Parisians have been buried in the Holy Innocents’ Cemetery[8].

Cemetery Transfers[edit]

During the final months of 1785, the transferring of bones from the the Holy Innocents’ cemetery began. The bones were gradually removed from the mass graves and the ground, then cleaned and piled up with forks into closed carriages. A scrupulous religious rite was observed: funeral wagons covered with black catafalques drove at dusk to the service shaft of the Tombe-Issoire quarries to dump their load. They follow church choirs carrying lanterns respecting the dead, accompanied by torchbearers and followed by priests singing the Office of the Dead (L’office des morts). At the end of the journey, the work was more brutal: the bones were thrown into a stone pit at what is now 21, avenue René-Coty[7].

On April 7th 1786, the catacombs were blessed by Abbots Motret, Maillet and Asseline, with architects such as Legrand and Molinos, and head of The Inspection générale des carrières , Charles-Axel Guillaumot[9].The work was carried out under Lenoir's successor, Louis Thiroux de Crosne, Lieutenant General of Police. The transfer took fifteen months and was a success. The administration consequently decided to carry out the measure with other Parisian cemeteries, in particular those adjoining the churches. They were emptied until January 1788 and then abolished. This lasted from 1787 to 1814. When the fruit and vegetable market was built under the First French Empire on the site of the Holy Innocents’ Cemetery, other bones were uncovered during the foundation work and followed the same path. Transfers finally resumed from 1842 to 1860, during which time no less than eight hundred carriages carrying the bones were sent to the temporary ossuary at Vaugirard, and then to the catacombs. Seventeen cemeteries, one hundred and forty-five monasteries, convents and religious communities, and one hundred and sixty places of worship surrounded by their own cemeteries fed the underground quarries. Finally, several years later, Haussmann's renovation of Paris discovered more undiscovered bones, which were in turn transported to the catacombs.[10]

At the bottom of the dumping shaft, men collected the bones that had been dumped in bulk, and loaded them onto wheelbarrows or small wooden carts to put them into the sector reserved for them in the underground rooms or galleries. Each location is marked with an engraved plaque indicating the origin and date of transfer. It is estimated that more than six million remains were moved in this way over the course of a century in a series of ossuaries in the 14th arrondissement that still exist under Paris, making it the largest visited cemetery in the world[10]. Among them, we can mention all the famous names of the French Revolution. For example, Charles-Axel Guillaumot, who was responsible for the development of the site and the transfer of the bones[8].

Following the revolutionary days of 28-29 August 1788, 28 April 1789, 10 August 1792, then the massacre in the prisons, and finally the days of September 1792, many burials were carried out in the ossuary. In particular, the bones from the Errancis cemetery, a plot of land to the east of the Parc Monceau, which was used as a cemetery in 1794, were placed there.

An unusual place to visit[edit]

The catacombs have aroused curiosity since their creation. In 1787, the first visitor, the Count of Artois, Charles X, went down there with the ladies of the Court. The following year, Madame de Polignac and Madame de Guiche visited. But it was not until 1806 that the first public visits were organised; which only took place on random dates for a privileged few [11].

It was Guillaumot's successor, Louis-Étienne Héricart de Thury who organised the first regular visits when he took up his post in charge of The Inspection Générale des Carrières (IGC) in July 1809. He had a black line drawn on the ceiling to serve as a guide for visitors. In 1810 and 1811, he had the ossuary fitted out with alignments of bones decorated with macabre or artistic motifs, and placed plaques bearing quotations engraved in stone from famous sacred, literary, philosophical or poetic texts, in typical French Empire fashion. The consolidation works were transformed into monuments in the cemetery. In addition, the ossuary was isolated from the rest of the underground quarries, giving an appearance close to that of the 21st century. In 1815, Héricart de Thury published the Description des catacombes de Paris, which all subsequent studies were then based upon[12]. In 1830, visits were prohibited following damage and overflow, and were only allowed again several years later, at a rate of four per year.

Héricart de Thury set up two cabinets, one for mineralogy exhibiting various botanic specimens and fossils, and the other devoted to bone pathology, showing bones carefully selected for osteological reasons, deformed skulls or skulls with non-standard proportions or rudimentary prostheses. These two cabinets clearly enhanced interest of people to visit, but they were filled in after the events of the Paris Commune in 1871 and their collections dispersed[13].

On May 16th 1814, Francis I, Emperor of Austria, who lived in Paris, visited the Catacombs. The Catacombs were accessed from a staircase located at 2, Place Denfert-Rochereau. But in 1833, the religious authorities were forced to close the ossuary by the police prefect Rambuteau as it was considered a sacred place unfit for visitors. Despite numerous requests, it was not until 1850 that four annual visits were once again organised. In 1867, and again in 1874, this number was increased to two per month, plus an additional one on All Souls' Day, the day after All Saints' Day, when an underground service was held for the repose of souls.

In 1860, Napoleon III went there with his son. Also in 1860, the photographer Nadar, a pioneer of aerial photography, was the first to produce a series devoted to underground Paris, in particular the catacombs and sewers[14]. In 1867, it was the turn of Oscar II of Sweden and the German Chancellor Bismarck to visit the catacombs. In May 1871, the fleeing communards took refuge in several quarries in Paris, including the catacombs. There, they were then mercilessly massacred by the Versailles army.

On April 2nd 1897, a secret concert was organised in the catacombs, which made headlines. Around a hundred guests from Paris received a mysterious invitation to appear in front of the entrance to the ossuary on Rue Dareau at 11 o clock. They were asked not to stop their car at this address for the sake of secrecy. The invitation began as follows: "Monsieur... is asked to attend the concert in the catacombs, organised by Messrs Pierres and Jouaneau, at eleven o’clock". At midnight, an orchestra of forty-five excellent musicians, recruited from artists from l’Opéra, performed several pieces for the occasion, including Chopin's Funeral March, Saint-Saëns's Danse macabre, the Chorale and Funeral March of the Persians, To the Catacombs, a poem by M. Marlit, was recited by its author, and finally the Funeral March from Beethoven's Eroica Symphony. The concert ended at two in the morning. Bones were then placed in piles between the pillars so that this type of event would not happen again [15].

The last known transfer of bones took place in December 1933 .

Until 1972, the visit was made with a candle through a route that has since undergone some modifications. Electricity was installed in 1983, to conserve bones[16].

Today[edit]

From 1983, the management of the site was transferred from the Inspection Générale des Carrières to the Direction des Affaires Culturelles de la ville de Paris. In May 2002, the catacombs officially became a site devoted to the history and memory of the capital, managed by the Carnavalet Museum,.

The Paris catacombs reopened on the 14th of June 2005 after eight months of closure for renovation. The work consisted of consolidating the vaults, reassembling the walls and servicing the lighting. On November 18th 2007, the catacombs closed again to carry out major work to bring them up to safety standards. This work, estimated to cost 430,000 euros, was financed entirely by La Direction des Affaires Culturelles de la Ville de Paris. They wanted to install fire alarms on the air handling units, as well as a device to prevent the spread of smoke. A new emergency staircase was also built in the middle of the tour to enable the public to evacuate quickly in the event of an incident. The modernisation of the reception area allows for automatic counting of the public between the entrance and exit of the galleries. Finally, fire doors were also installed at the bottom of the access stairs.

On the 13th of September 2009, the catacombs were vandalised[17], which led to a three-month closure to the public and 40,000 euros of restoration work, mobilising a permanent team of four workers[18].

In 2015, the municipal ossuary of Paris was visited by more than 500,000 people.

Features[edit]

Description[edit]

The two-kilometre-long tour takes at least forty-five minutes. The catacombs are in the form of tunnels, inside of which, the temperature is constantly 14°C. There are 130 descending steps and 83 ascending steps.[19].

Entrance galleries[edit]

Aqueduc d'Arcueil et atelier[edit]

The visit to the Catacombs begins at 1, avenue du Colonel-Henri-Rol-Tanguy (Place Denfert-Rochereau), in the immediate vicinity of one of the excise office buildings built by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, which until 2017 housed The Inspection Générale des Carrières. After the small ticket office, a staircase of one hundred and thirty steps gives access, twenty metres below, to small rooms, displaying panels with information on the history of the catacombs as well as temporary exhibitions. From 2010 to 2012, for example, an exhibition was devoted to photographs of the Capuchin catacombs of Palermo.

A gallery leads out of the catacombs towards the south, under the Avenue René-Coty, formerly the Avenue du Parc-de-Montsouris. Further on, the route follows the narrow galleries used to consolidate L’Aqueduc d’Arcueil, built for Marie de Médicis to supply water to Luxembourg Palace. These consolidations were carried out by Guillaumot following several collapses in March 1782 and May 1784, due to water infiltration. The aqueduct is supported by a massive brick structure, bordered by two walled-galleries, linked from place to place by transverse galleries. Since the construction of Avenue Reille in 1860, which interrupted the aqueduct's course, this section has stayed dry[20].

The visitor then enters l’Atelier, i.e. the old Lutetian limestone quarries, which look untouched and have numerous gallery exits closed off by railings. This is one of the few sectors of the underground quarries that has retained its appearance at the end of its operation. The quarry head is supported by turned pillars (taken from the mass) or by arms (formed by overlapping stones) and the walls are formed by hagues keeping the fillings intact. A gently sloped corridor provides access to the lower levels[16],[21].

Port-Mahon Galler[edit]

The visitor enters the Port-Mahon gallery (Galerie de Port-Mahon). These sculptures were made in stone between 1777 and 1782 by a quarryman named Décure, known as Beauséjour, a veteran of Louis XV's armies. According to Le Conducteur portatif of 1829, he was a soldier who enlisted in Richelieu's army in 1756 during the reconquest of Minorca. After being discharged, he joined the Quarry Inspectorate to supplement his modest pay. He worked during the day on consolidation work under the supervision of Guillaumot, he sculpted after his work and presented a model as well as various views of Port-Mahon, the main town on the island of Minorca, in the Balearic Islands, where he had was once a prisoner of the English. In order to complete his work, he started to create a staircase from the upper level of the quarry, but this caused a sinkhole that killed him instantly[22],[23].

These sculptures, which were damaged during the Revolution, were restored in 1854, and on several occasions since then.

Quarryman's footbath[edit]

A short distance away, the quarrymen's footbath is a small well containing a very clear body of water, which was once used by workers during consolidation works on the ossuary. Equipped with a guardrail, it owes its name to the water’s clearness, which makes it hardly visible to the unsuspecting visitor who would get his feet wet walking down the last immersed steps of the staircase. This feature was constantly used by the guides accompanying the visitors until the installation of electric lighting in 1983. This well is the first geological drilling to be carried out under Paris, the oryctognostic section of which was taken in 1814 by Héricart de Thury. It was made to identify the geological constitution of the subsoil. The gallery gains height in the passage known as the « doubles carrières ». The visitor then reaches the ossuary, whose vestibule is also used for temporary exhibitions.[24]

The Ossuary[edit]

People enter the ossuary through a metal door surrounded by two pillars decorated with white geometric patterns on a black background, whose lintel is inscribed with a mournful warning: « Arrête ! C'est ici l'empire de la mort. » (Stop! This is the empire of death). This alexandrine is taken from l'Énéide (chant VI) by Jacques Delille. It is the sentence with which Aeneas is greeted by Charon, who rows the boat to cross the Styx to reach the underworld. On the left wall of the first room, a plaque commemorates the creation of the ossuary.

Six million French bones lie in approximately 780 metres of galleries, mostly inaccessible to the public, at an average height of one and a half metres. Their total surface area is 10,933 metres squared. On either side of the tour route, the bones form long rows of femur or tibia heads, of which only the apophyses can be seen. Friezes made up of skulls are arranged at several heights and slightly protrude from these walls of bones, displaying a romantic-macabre decorative approach. However, at the back of these alignments, thousands of skeletons remain in a mess. Engraved plaques show the origin and year of transfer in front of the bones; others may bear striking French or Latin[25] quotations from great authors, or other renowned people of the early nineteenth century.

In the middle of a gallery that widens into a rotunda, the Samaritan fountain was built in 1810 to collect the water from the groundwater table, which was discovered by workers during the construction of the ossuary. It is a nod to the story of Christ and the Samaritan at Jacob's well, alluded to from the inscription: « Quiconque boit de cette eau aura encore soif. Mais celui qui boira de l'eau que je lui donnerai n'aura point soif dans l'éternité… ». (Whoever drinks from this water will thirst again. But whoever drinks from the water that I shall give him shall not ever thirst again) It was also called the « source de Léthé » or « de l'oubli », by resemblance with the river in Greek mythology, where the souls of the dead quenched their thirst to forget the circumstances of their existence[26],[27].

Further on, a larger room or chapel, known as the «crypte du sacellum », has an altar, where the liturgy of deaths was celebrated for a long time. The altar, a reproduction of an ancient tomb discovered in 1807 on the banks of the Rhône between Vienne and Valence, is in fact a disguised consolidation, made due to a landslide in 1810. The monument has an engraving: “Asleep in death, here are our ancestors”. The room also has a large white cross and small stone stools[27].

After the bend in the gallery, a stone column topped by an antique-shaped basin, known as a "sepulchral lamp", stands in a nook. This monument, was used to burn pitch resin as the air was gradually corrupted by bone deposits which made the air difficult to breathe for the workers, who transferred bones. It was also the first of its kind to be built in the ossuary. The maintenance of a fireplace was the best way to ensure ventilation during underground work. It was used to improve visibility and, more prosaically, to improve air circulation before the construction of ventilation shafts[28].

The visit then leads to "« tombeau de Gilbert » or « sarcophage du lacrymatoire »", which is only a tomb by name because it is actually a consolidation. It is dedicated to Nicolas Gilbert (1750-1780), a poet whose verses are engraved on the monument. It was the mining engineer Caly who came up with the unusual idea of building this fake tomb amidst thousands of unburied bones. The following galleries contain the remains of the victims of des combats des Tuileries et de la Révolution[28].

Further on is the only tombstone in the ossuary: that of Françoise Gellain (or Dame Legros), whose tombstone was transferred from the emptied Cimetière de Vaugirard in 1860. This woman fell in love with a prisoner in the Bicêtre prison without ever having seen him after she found his note thrown from a window. The prisoner was the writer Jean Henry, also known as Latude (1725-1805). She then devoted her life to getting him released. Having succeeded, she was awarded a prize for virtue by the Académie Française in 1784 [29]. Near the exit of the ossuary, a vast room entirely surrounded by bones, known as the « crypte de la Passion » or « rotonde des tibias », has a strange barrel-shaped sculpture of bones. This is made up exclusively of tibias, around a pillar. It was in this room that the secret concert took place on April 2nd 1897. A massive door leads out of the ossuary[30].

Exit[edit]

On the way out, a straight gallery, where consolidation work was carried out in 1874 and 1875, dug eighteen metres under the Rue Rémy-Dumoncel, has three sinkholes. Instead of being filled in, two of them were emptied by the workers, who took advantage of the natural vault, which was stabilised by sprayed cement in order to show the geological layers that overlie the quarries. It is consolidated by eleven-metre high masonry, and the different geological strata are painted in different colours. A spiral staircase with 83 steps leads back to the surface at 36, rue Rémy-Dumoncel[31],[23].

A guard watches over the exit, to prevent entrance to the site by the end of the route, but above all to check bags, so that no visitor leaves the catacombs with bones. A bone removal constitutes a violation of a burial site under the law, punishable by one year's imprisonment and a fine of 15,000 euros. The Paris City Council warns that legal proceedings will be taken in the event of damage to or theft of bones.

Interesting Facts[edit]

The catacombs contain the bones of more than six million Parisians, including many renowned figures from French history. But their remains are buried with millions of unknown Parisians who, to this day, have not been identified. .

Charles-Axel Guillaumot, Premier Inspecteur général des carrières et chargé des consolidations et transferts d'ossements, was buried in 1807 in the Sainte-Catherine cemetery, the contents of which were later moved to the catacombs. Several famous figures in French history found their final resting place in the ossuary: Nicolas Fouquet, superintendent of finances under Louis XIV, was buried in the convent of the Filles-de-la-Visitation-Sainte-Marie, transferred in 1793; the minister Colbert, was buried in a vault in Saint-Eustache church, desecrated during the Revolution and transferred to the Catacombs.[32].

The remains of Rabelais, François Mansart, Jules Hardouin-Mansart, The Man in the Iron Mask (an unidentified political prisoner, famous in French history and legend, who died in the Bastille in 1703, during the reign of Louis XIV) (reference - britannica/wikipedia) and Jean-Baptiste Lully were transferred to the catacombs from the church of Saint-Paul. Those transported from Saint-Étienne-du-Mont include Racine, Blaise Pascal and Marat, from Saint-Sulpice and Montesquieu; from the Saint-Benoît cemetery, those of the engravers Guillaume Chasteau and Laurent Cars, of Charles and Claude Perrault, as well as Héricart de Thury, uncle of Louis-Étienne, l'inspecteur des carrières. From the Ville-l'Évêque cemetery came the bodies of the 1,000 Swiss Guards massacred at the Tuileries in 1792 as well as the 1,343 people guillotined at the Carrousel or Place de la Concorde between 1792 and 1794, including Charlotte Corday. With the transfer of the bones from the Errancis cemetery under the Restoration, Danton, Camille Desmoulins, Lavoisier and Robespierre also joined the catacombs[32].

Based on claims, there are three others which should be highlighted: the poet Nicolas Gilbert, buried in the Hôtel-Dieu cemetery, known as Clamart,48 was transferred to the catacombs when the cemetery was evacuated. He is thus drowned in the mass while a monument in the form of a tomb commemorates him. The martyr St Ovide, was buried in the catacombs of Rome, but was then brought back to Paris by Pope Alexander VII. His remains were placed in the Capuchin Convent, whose bones were transferred to the catacombs on March 29th 1804. This means that he is the only person to have been buried in two catacombs[33]. The acroterial tomb of Philibert Aspairt and the discovery of his body in 1804 are thought to be a hoax by L'inspecteur des Mines[34].

Site management[edit]

Administration[edit]

The Carnavalet-History of Paris Museum, was entrusted with the management of the catacombs in May 2002.

The administration is carried out by the director of the museum, the secretary general and one of its curators, from the point of view of the scientific council. The cultural services technician, responsible for the surveillance and security in the Carnavalet Museum, supervises the on-site team. The overall cost of running the Carnavalet Museum, the catacombs and La Crypte Archéologique du Parvis Notre-Dame was seven million euros in 2004 .

While the municipality decided to make access to the city's museums free of charge in 2002, there is still a payment needed to access the catacombs. According to the city council, this payment is because of the temporary exhibitions presented permanently in the site museum. This is the case with La Crypte Archéologique du Parvis Notre-Dame as well. However, these exhibitions, which are limited to a few panels or photos, appear to be too limited to justify the entrance fee according to an audit report by the Inspection générale de la ville de Paris.

In 2006, fifteen people worked on site (full-time equivalent), welcoming visitors, monitoring and ensuring security. Until then, the lack of staff meant that only visitors could be in the catacombs at the same time. Since 2006, two hundred people have been allowed in together. The conditions of the large, dark, humid site, means that more staff is needed than in other attractions in the city, but the conditions also pose a recruitment problem. This situation caused a delay in the reopening of the site in 2008 following a social movement, as the working conditions were demanding and demotivating. Two security guards work in the basement for two-hour periods; they alternate between the reception and exit of the site.

Visitors[edit]

The number of visitors of the site is quite high and has grown steadily over the years. However, the long periods of closure in 2004 and 2005, at the end of 2007, the beginning of 2008 and the end of 2009, mean that the figures do not accurately reflect the growing demand52. With 252,959 visitors in 2007, the catacombs were the fourth most visited museum in the city, after the Petit Palais, Le Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and Le Musée Carnavalet.

The capacity of the site has been limited to 200 visitors at a time, despite consecutive building campaigns, and the growing attraction of the catacombs, the capacity means that every day a queue of several hundred metres forms around the entrance and, at peak times, there is often a wait time of several hours.

Pricing policy and services to the public[edit]

The Catacombs Museum was open to the public from Tuesday to Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., but the closing time has been extended to 8 p.m. since 2 September 2014, and then later 8.30 p.m, with the last entry being one hour before closing time. On Mondays and public holidays, all museums are closed. It is a site museum, and therefore remains a pay-to-visit museum, unlike Les Musées de Collections de la Ville de Paris, which are free to visit following a decision by the city council in 2002. The tariffs are set by the museum office, with the agreement of the head of the institution, and set by a municipal decree each year.

In 2018, the entrance fee for individual visitors was 13 euros, with a reduced fee of 11 euros for teachers or 18-26 year olds, and free admission for under 18s, unemployed people, and people on social welfare, among others. Up to the age of thirteen, an accompanying adult is compulsory.

The museum offers a self-service tour brochure, which can be downloaded from the official website, It is only available in French, English and Spanish.

The layout of the site limits the services offered to the public due to the very cramped entrance. For this reason, there are no toilets or cloakrooms. Similarly, there is no shop on the site; only a commercial site, located opposite the catacomb exit pavilion, and with no link to the city, the shop has offered souvenirs to visitors since August 2010. The presence of numerous steps and the long underground journey through often narrow galleries make access to the site impossible for people with reduced mobility. In June 2017, a new exit at 21 bis avenue René-Coty, incorporated a wider staircase, a shop, toilets and an exhibition space, improved this situation. A new entrance to the neighbouring Ledoux Pavilion was introduced in late 2019 .

Other Catacombs in Paris[edit]

The catacombs of La Tombe-Issoire are the most famous and attract many visitors. But other catacombs exist under Paris. Since they are inaccessible to the public, they remain relatively unknown[35].

In the 19th century, the lack of surface space led to the creation of three large cemeteries outside the city, those of Montmartre, Montparnasse and Père-Lachaise, and the continued transfer of bones from the old reformed cemeteries into the catacombs. But this was without taking into account the rapidly growing population and continuing urbanisation. In 1860, the newly created catacombs were integrated into the city, and in turn found themselves without any possibility of extension. The ossuary of La Tombe-Issoire itself got saturated, and that led to the need to find new places to transfer the bones from the cemeteries.

The Montparnasse Cemetery was eroded by quarries and required consolidation work. For this reason, the city of Paris decided to open new bone repositories under the large cemetery in March 1859, after being unsure about the Chartreux quarries. These new spaces were primarily intended for anonymous bones from mass graves. A quarry shaft was used in the same way as at La Tombe-Issoire, and some of the galleries were filled with the remains of victims of the great cholera epidemics of the early 19th century. A total of seven deposits under the Montparnasse cemetery were gradually filled with bones, in addition to those discovered by chance during major roadworks. Over the following decades, these catacombs were regularly robbed by ignorant cataphiles (secret visitors of the catacombs) looking for ’souvenirs’[36],. Today, they are known as the "Carrefour des Morts" (Crossroads of the Dead) by the regular visitors.

In the third year of the Republic, a citizen named Delamalle explained, after attending his mother's funeral, that he was outraged by the conditions of burial of the poor people in the Montmartre catacomb. The coffin was, like the others, thrown into old quarry pits. In year IV of the Republic, Camby took the idea which had already been proposed before him, and proposed the installation of catacombs in the careers of Montmartre. He imagined a true underground cemetery, that "rich families would embellish with marbles and paintings". The project remained unfinished, but in 1810, Héricart de Thury took up the idea and proposed the creation of an underground cemetery, this time under the Père-Lachaise cemetery. The vast galleries, fifteen metres high and eight metres wide, would not be used as ossuaries, but would be designed to accommodate monumental tombs. However, this idea was also not pursued and priority was given to the surface cemetery[36].

After the Second World War, however, the persistent lack of space led to the creation of a catacomb. The Père-Lachaise cemetery became full and it was not possible to further expand in an environment that had become completely urbanised over time. It was in this context that the Cemetery Conservation Department took up Héricart de Thury's modernised idea. In 1950, the construction of a gigantic catacomb was undertaken under the surface cemetery, in order to receive the contents of abandoned and ruined graves.

At the end of the main alley, a three-storey concrete underground complex was dug into the green marl and gypsum at a cost of 157 million francs. Access is through two trapezoidal stone doors on either side of the war memorial. Concrete galleries run beneath the hillside, leading to a multitude of small rooms with cells, designed to hold the contents of one hundred vaults. When a plot is abandoned, the bones are not dumped in a jumble like in other catacombs, but are placed in a small wooden box with the names of the deceased, these boxes can hold up to six skeletons. Once a room has been filled, it is walled up with a stone inscribed with the names of those buried there[37],.

Other ossuaries similar to the catacombs were also built at the gates of Paris, in quarries close to the great southern network of Paris, under the cemeteries of Montrouge and Kremlin-Bicêtre.

Cataphilia[edit]

The catacombs refer, by metonymy and by an improper use of the term, to the whole network of tunnels in the old underground limestone quarries, a general network nowadays called the Grand Réseau Sud (GRS)[38]. Anyone who enters the catacombs in Paris and goes through the tunnels is thus called a cataphile.

In 1983, Barbara Glowczewski and Jean-François Matteudi’s book, La Cité des cataphiles. Mission anthropologique dans les souterrains de Paris (The City of Cataphiles: An Anthropological Mission in the Underground of Paris) popularised the existence of the secret walks through the catacombs. The numerous articles that appeared after this book was released caused a significant increase in the number of visitors, to the point where it became a phenomenon. Although this phenomenon has slowed down over the years, it has continued with many associations related to caving, heritage protection and other visitors.

Catacombs in fiction[edit]

Literature[edit]

The catacombs have not been well represented in literature. The first novels dedicated to them only date from the 1830s. Although Élie Berthet, Pierre Zaccone, Joseph Méry and Gaston Leroux described the catacombs of Paris in the nineteenth century, playing on the romantic aspects associated with the catacombs and fairytales about them, the following century involved little mention of this environment.

In World War Z by Max Brooks, one chapter mentions events taking place in the catacombs of Paris

The catacombs also play an important role in the novel L'équilibre du Funambule by Céline Knidler.

- Pierre Tchernia's Les Gaspards (1974), where a group of people opposed to construction works in Paris lived in the catacombs as part of an established community in Paris’ underground networks

- Catacombs by David Elliot and Tomm Coker (2007)

- Paris by Cédric Klapisch (2008) ;

- Catacombes (As Above, so Below) by John Erick Dowdle (2014) a horror film that deals with urban legends about the catacombs.

Television[edit]

Catacombs in television :

- La Nouvelle Malle des Indes (1982), when Thomas Waghorn and his friend Martial Sassenage were locked away in the catacombs so that they could not complete their journey to India82.

- Bleu catacombes, crime film by Charlotte Brändström broadcast in 2014.

- Nox, TV series by Mabrouk El Mechri broadcast in 2018.

- Lupin, Netflix series, released in 2021.

Video games[edit]

The unusual world of the catacombs has inspired video game designers:

- In Deus Ex, players must go through part of the catacombs to reach certain locations in the city without facing the militia present on the surface, in reference to the Forces françaises de l'intérieur using the tunnels during the German occupation. The catacombs are home to a secret group of French revolutionaries called Silhouette, who take refuge in the underground83.

- In Medal of Honor: Resistance (mission 2 of the story mode), the player travels through the catacombs where they encounter Nazis. The mission is to seal the catacomb entrances with planted explosives; the player must also find papers hidden in a corner of the catacombs; at the end, the player exit the catacombs and (can) kill the Nazis guarding the exit of the catacombs and get into the back of a black car to finish the mission.

- In The Saboteur, the player must cross through part of the catacombs to warn the Resistance (who are hiding in the catacombs) that the Nazis know where they are hiding.

- In Nightmare Creatures II, one scene took place in the catacombs and the cemetery above it is presented as Père-Lachaise.

- In Resistance: Retribution, James Grayson enters Paris through the catacombs.

- More recently, in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3, the player chases a war criminal through the catacombs of Paris.

- In Assassin's Creed Unity, Arno Dorian enters the catacombs.

Notes et références[edit]

- ^ Les Saints-Innocents. Michel, Fleury, Guy-Michel,. Leproux, Paris. Délégation à l'action artistique. Paris: Délégation à l'action artistique de la Ville de Paris. [1990?]. ISBN 2-905118-31-8. OCLC 490177954.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Saletta, Patrick. À la découverte des souterrains de Paris. pp. p.96.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Collectif, Atlas du Paris souterrain, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)110.

- ^ Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)97.

- ^ a b Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)98.

- ^ Gilles Thomas (2015). Les Catacombes. Histoire du Paris souterrain. Passage. p. 9..

- ^ a b Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)99.

- ^ a b Collectif, Atlas du Paris souterrain, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)111.

- ^ Xavier Ramette; Gilles Thomas (2012). Inscriptions des catacombes de Paris. Le Cherche Midi. p. 17..

- ^ a b Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)100.

- ^ Catherine Grive (2009). La France étrange et secrète (in French). Paris: Petit Futé. p. 91. ISBN 978-2-84768-186-4.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help); Unknown parameter|ignore-isbn-error=ignored (|isbn=suggested) (help). - ^ Ce livre a été réédité aux éditions du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques (CTHS), coll. « Format 36 », Paris, 2000 ISBN 978-2-7355-0424-4.

- ^ Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)101.

- ^ Base Mistral du ministère de la Culture, photographies de Nadar : Paris souterrain.

- ^ Adélaïde Barbey et Francoise Vibert-Guigue (1990). Paris. Hachette. p. 186..

- ^ a b Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)102.

- ^ « Les catacombes vandalisées », Le Parisien, 16 septembre 2009.

- ^ « Les catacombes enfin rouvertes au public », Le Parisien, 22 décembre 2009.

- ^ "Site officiel des catacombes, présentation". catacombes.paris.fr. Retrieved 26 mars 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help). - ^ Collectif, Atlas du Paris souterrain, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)112.

- ^ Collectif, Atlas du Paris souterrain, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)113.

- ^ Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)104.

- ^ a b Collectif, Atlas du Paris souterrain, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)123.

- ^ Collectif, Atlas du Paris souterrain, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)122.

- ^ Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)107.

- ^ Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)110.

- ^ a b Collectif, Atlas du Paris souterrain, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)114.

- ^ a b Collectif, Atlas du Paris souterrain, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)115.

- ^ Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)112.

- ^ Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)114.

- ^ Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)115.

- ^ a b Collectif, Atlas du Paris souterrain, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)119.

- ^ Collectif, Atlas du Paris souterrain, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)118.

- ^ A. Guini-Skliar, M. Viré, J. Lorenz, J.-P. Gély et A. Blanc (2000). Paris souterrain. Les carrières souterraines (in French). Cambrais: Nord Patrimoine. p. 83. ISBN 2-912961-09-2.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - ^ Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)117.

- ^ a b Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)118.

- ^ Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)119.

- ^ Gilles Thomas (2011). "La fa(r)ce cachée des grandes écoles : les "catacombes" offertes à leurs élèves !". In Situ (17): 6..

Annexes[edit]

Catégorie:Catégorie Commons avec lien local identique sur Wikidata

Related articles[edit]

- Carrières souterraines de Paris

- Carrière du chemin de Port-Mahon

- Liste des musées parisiens

- Carrière de calcaire

Bibliography[edit]

- Basile Cenet, Vingt mille lieux sous Paris, éditions du Trésor, 2013, 275 p. ISBN 979-1091534024.

- Clément, Alain (2001). Atlas du Paris souterrain. La doublure sombre de la Ville Lumière (in French). Paris: Parigramme. p. 200. ISBN 978-2-84096-191-8. OCLC 248291921..

- Barbara Glowczewski et Jean-François Matteudi, La Cité des cataphiles. Mission anthropologique dans les souterrains de Paris, Librairie des Méridiens, [1983], 1996.

- Louis-Étienne François Héricart-Ferrand, vicomte de Thury, Description des catacombes de Paris, 1815, Lire en ligne.* Liehr, Günter; Olivier Faÿ (2007). Les Souterrains de Paris. Légendes, mystères, contrebandiers, cataphiles (in French). Romagnat: De Borée. p. 187. ISBN 978-2-84494-634-8. OCLC 470841069..

- Charles Kunstler, Paris souterrain, Flammarion, 1953.

- Xavier Ramette et Gilles Thomas, Inscriptions des catacombes de Paris, Le Cherche Midi, 2012 ISBN 978-2749124742.

- Patrick Saletta, À la découverte des souterrains de Paris, Sides, 1990, 334 p. ISBN 978-2-86861-075-1.

- Gilles Thomas, Les Catacombes de Paris, Parigramme, 2014, 122 p. ISBN 978-2-84096-890-0.

- Gilles Thomas, Les Catacombes. Histoire du Paris souterrain, Passage, coll. « La petite colle », 2015, 290 p. ISBN 978-2847422504.

- J. Tomasini, Les Catacombes de Paris, brochure éditée par le service de l'Inspection générale des carrières, 32 p., s. d.

- …plus de livres en français sur ce sujet

External links[edit]

- No URL found. Please specify a URL here or add one to Wikidata.

- Ressource relative au tourisme :

- Muséofile

- Les Catacombes sur le portail de la ville de Paris

[[Category:Paris Musées]] [[Category:Catacombs]] [[Category:14th arrondissement of Paris]] [[Category:Urban exploration]] [[Category:Museums in Paris]] [[Category:Monuments and memorials in Paris]] [[Category:Cemeteries in Paris]] [[Category:WikiProject Europe articles]] [[Category:WikiProject France articles]]