User:Louis P. Boog/sandbox/Quranic criticism

| Quran |

|---|

TO DO *WHEN COMPLETED *update, edit History_of_the_Quran#Origin_according_to_academic_historians

*READ and CHECK *read and add MUSLIM WORLD https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1478-1913.1993.tb03571.x

*check HCL databases for "The battle of the books, The business of marketing the Bible and the Koran says a lot about the state of modern Christianity and Islam

*https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IBUhCG3Fbck What are the seven different readings (qira'at) of the Qur'an? Dr. Shabir Ally explains *trim out anti-Islamic parts

- TOOLS/REFERENCES

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Manual_of_Style/Islam-related_articles

- Wikipedia:Manual of Style/Islam-related articles

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template:Cite_Quran

- multiple Quranic translations: https://www.islamawakened.com/quran/2/219/default.htm

- 56:78 56:78 (Pickthall)

THEMES:

- investigating and verifying the Quran's origin, text, composition, history

- variations in text among different versions/manuscripts;

- the intended audience (such as whether the audience was assumed to be familiar with the Christian Bible);

- puzzles of unclear letters, words and phrases, unexplained by early exegetes;

- themes and stories found in other earlier texts[9] (such as narratives about Alexander the Great) and earlier religious works (especially the bible, apocryphal gospels and Jewish legends);[10]

- patterns and repetition of text suggesting oral transmission,

[What to do? 21- march 2021 Below has become to much of a mess. plan now is to start by going directly to the article improving 1) the Early Quranic manuscripts 2) legends/stories

Historical reliability of the Quran [current name and version][edit]

| Quran |

|---|

Historical reliability of the Quran concerns the question of the historicity (i.e. history as opposed to historical myth, legend, or fiction) of the described or claimed events in the Quran.

[NOTE: this article should be totally rewritten or merged with another]

The Quran is viewed to be the scriptural foundation of Islam and is believed by Muslims to have been sent down by Allah (God) and revealed to Muhammad by the angel Jabreel (Gabriel). Muslims have not used historical criticism in the study of the Quran, but they have used textual criticism in a similar way used by Christians and Jews.[1] It has been practiced primarily by secular, Western scholars such as John Wansbrough, Joseph Schacht, Patricia Crone, and Michael Cook, who set aside doctrines of the Quran's divinity, perfection, unchangeability, etc., accepted by Muslim scholars,[2] and instead investigate the Quran's origin, text, composition, and history.[2]

In the Muslim world, scholarly criticism of the Quran can be considered an apostasy. Scholarly criticism of the Quran, is thus, a beginning area of study in the Islamic world.[3][4]

Scholars have identified several pre-existing sources for some Quranic narratives.[5] The Quran assumes its readers' familiarity with the Christian Bible and there are many parallels between the Bible and the Quran. Aside from the Bible, the Quran includes legendary narratives about Dhu al-Qarnayn, apocryphal gospels,[6] and Jewish legends.

Textual history[edit]

Early manuscripts[edit]

In the 1970s, 14,000 fragments of Quran were discovered in the Great Mosque of Sana'a, the Sana'a manuscripts. About 12,000 fragments belonged to 926 copies of the Quran, the other 2,000 were loose fragments. The oldest known copy of the Quran so far belongs to this collection: it dates to the end of the 7th–8th centuries.

The German scholar Gerd R. Puin has been investigating these Quran fragments for years. His research team made 35,000 microfilm photographs of the manuscripts, which he dated to early part of the 8th century. Puin has not published the entirety of his work, but noted unconventional verse orderings, minor textual variations, and rare styles of orthography. He also suggested that some of the parchments were palimpsests which had been reused. Puin believed that this implied an evolving text as opposed to a fixed one.[7]

In 2015, some of the earliest known Quranic fragments, dating from between approximately AD 568 and 645, were identified at the University of Birmingham.[8] Islamic scholar Joseph E. B. Lumbard of Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Qatar has written in the Huffington Post in support of the dates proposed by the Birmingham scholars. Professor Lumbard notes that the discovery of a Qur'anic text that may be confirmed by radiocarbon dating as having been written in the first decades of the Islamic era, and includes variations in the “under text.” recorded in the Islamic historiographical tradition .[9] [unreliable source?]

Quran and History[edit]

Creation narrative and the Flood[edit]

The Quran contains a creation narrative and may refer to the world being created in six days (The word يوم yawm which in some places is translated as day, refers to other meanings as well depending upon in which context it is being used. Stages, period, or phases are some other meanings of the same word), although this is highly debatable. In Sūrah al-Anbiyāʼ, the Quran states that "the heavens and the earth were of one piece" before being parted.[10] God then created the landscape of the earth, placed the sky above it as a roof, and created the day and night cycles by appointing an orbit for both the sun and moon.[11] Some Muslim apologists, like Zakir Naik and Adnan Oktar advocate creationism. Some British Muslim students have distributed leaflets on campus, advocating against Darwin's theory of evolution[12] and contemporary Islamic scholar Yasir Qadhi believes that the idea that humans evolved is against the Quran.[13] It has to be noted, however, that not all Muslims are against the theory of evolution, Some Muslims point to a verse in the Quran as evidence for Evolution “when He truly created you in stages ˹of development˺?” Verse 71:14. Evolution is taught in many Islamic countries, and some scholars have tried to reconcile the Quran and evolution.[14]

Quran also contains the flood narrative. According to the Quran, Noah was a prophet for 950 years,[15] and he built an ark where he filled it with pairs of animals.[16] People who did not believe him, including one of his own sons, are said to have drowned.[17]

Samiri[edit]

Quran recounts a story of the golden calf, where it mentions that Samiri, a rebellious follower of Moses, created the calf while Moses was away for 40 days on Mount Sinai, receiving the Ten Commandments.[18] Due to the fact that as-Samiri can mean the Samaritan,[19] some believe that his character is a reference to the worship of the golden calves built by Jeroboam of Samaria, conflating the two idol-worshiping incidents into one.

Death of Jesus[edit]

Quran maintains that Jesus was not actually crucified and did not die on the cross. The general Islamic view supporting the denial of crucifixion was probably influenced by Manichaenism (Docetism), which holds that someone else was crucified instead of Jesus, while concluding that Jesus will return during the end-times.[21]

That they said (in boast), "We killed Christ Jesus the son of Mary, the Messenger of Allah";- but they killed him not, nor crucified him, but so it was made to appear to them, and those who differ therein are full of doubts, with no (certain) knowledge, but only conjecture to follow, for of a surety they killed him not:-

Nay, Allah raised him up unto Himself; and Allah is Exalted in Power, Wise;-

Despite these views, theologians maintain that the Crucifixion of Jesus is a fact of history.[23] The view that Jesus only appeared to be crucified and did not actually die predates Islam, and is found in several apocryphal gospels.[21]

Irenaeus in his book Against Heresies describes Gnostic beliefs that bear remarkable resemblance with the Islamic view:

He did not himself suffer death, but Simon, a certain man of Cyrene, being compelled, bore the cross in his stead; so that this latter being transfigured by him, that he might be thought to be Jesus, was crucified, through ignorance and error, while Jesus himself received the form of Simon, and, standing by, laughed at them. For since he was an incorporeal power, and the Nous (mind) of the unborn father, he transfigured himself as he pleased, and thus ascended to him who had sent him, deriding them, inasmuch as he could not be laid hold of, and was invisible to all.-

— Against Heresies, Book I, Chapter 24, Section 40

Irenaeus mentions this view again:

He appeared on earth as a man and performed miracles. Thus he himself did not suffer. Rather, a certain Simon of Cyrene was compelled to carry his cross for him. It was he who was ignorantly and erroneously crucified, being transfigured by him, so that he might be thought to be Jesus. Moreover, Jesus assumed the form of Simon, and stood by laughing at them.[24][25] Irenaeus, Against Heresies.[20]

Another Gnostic writing, found in the Nag Hammadi library, Second Treatise of the Great Seth has a similar view of Jesus' death:

I was not afflicted at all, yet I did not die in solid reality but in what appears, in order that I not be put to shame by them

and also:

Another, their father, was the one who drank the gall and the vinegar; it was not I. Another was the one who lifted up the cross on his shoulder, who was Simon. Another was the one on whom they put the crown of thorns. But I was rejoicing in the height over all the riches of the archons and the offspring of their error and their conceit, and I was laughing at their ignorance

Coptic Apocalypse of Peter, likewise, reveals the same views of Jesus' death:

I saw him (Jesus) seemingly being seized by them. And I said 'What do I see, O Lord? That it is you yourself whom they take, and that you are grasping me? Or who is this one, glad and laughing on the tree? And is it another one whose feet and hands they are striking?' The Savior said to me, 'He whom you saw on the tree, glad and laughing, this is the living Jesus. But this one into whose hands and feet they drive the nails is his fleshly part, which is the substitute being put to shame, the one who came into being in his likeness. But look at him and me.' But I, when I had looked, said 'Lord, no one is looking at you. Let us flee this place.' But he said to me, 'I have told you, 'Leave the blind alone!'. And you, see how they do not know what they are saying. For the son of their glory instead of my servant, they have put to shame.' And I saw someone about to approach us resembling him, even him who was laughing on the tree. And he was with a Holy Spirit, and he is the Savior. And there was a great, ineffable light around them, and the multitude of ineffable and invisible angels blessing them. And when I looked at him, the one who gives praise was revealed.

However, Islamic scholar Mahmoud M. Ayoub and historian of religion Gabriel Said Reynolds disagree with the mainstream interpretation of the Quranic narrative of Jesus' death, arguing that the Quran nowhere disputes that Jesus died.[26][27]

See also[edit]

- Historicity of the Bible

- Criticism of the Quran

- History of the Quran

- Corpus Coranicum

- Syriac Infancy Gospel

- Noah in Islam

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Religions of the world Lewis M. Hopfe – 1979 "Some Muslims have suggested and practiced textual criticism of the Quran in a manner similar to that practiced by Christians and Jews on their bibles. No one has yet suggested the higher criticism of the Quran."

- ^ a b LESTER, TOBY (January 1999). "What Is the Koran?". Atlantic. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ Christian-Muslim relations: yesterday, today, tomorrow Munawar Ahmad Anees, Ziauddin Sardar, Syed Z. Abedin – 1991 For instance, a Christian critic engaging in textual criticism of the Quran from a biblical perspective will surely miss the essence of the quranic message. Just one example would clarify this point.

- ^ Studies on Islam Merlin L. Swartz – 1981 One will find a more complete bibliographical review of the recent studies of the textual criticism of the Quran in the valuable article by Jeffery, "The Present Status of Qur'anic Studies," Report on Current Research on the Middle East

- ^ Leirvik 2010, p. 33.

- ^ Leirvik 2010, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Lester, Toby (January 1999). "What Is the Koran?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ Coughlan, Sean (22 July 2015). "'Oldest' Koran fragments found in Birmingham University". BBC News. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "New Light on the History of the Qur'anic Text?". The Huffington Post. 24 July 2015.

- ^ Quran 21:30

- ^ Quran 21:31–33

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (21 February 2006). "Academics fight rise of creationism at universities" – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ "Muslim thought on evolution takes a step forward | Salman Hameed". TheGuardian.com. 11 January 2013.

- ^ webmaster (6 December 2011). "Are evolution and religion compatible?". The Stream - Al Jazeera English.

- ^ "Surah Al-'Ankabut [29:14]". Surah Al-'Ankabut [29:14].

- ^ "Surah Hud [11:35-41]". Surah Hud [11:35-41].

- ^ "Surah Al-A'raf [7:64]". Surah Al-A'raf [7:64].

- ^ The Qur'an, Surah Ta Ha, Ayah 85

- ^ Rubin, Uri. "Tradition in Transformation: the Ark of the Covenant and the Golden Calf in Biblical and Islamic Historiography," Oriens (Volume 36, 2001): 202.

- ^ a b "Et gentibus ipsorum autem apparuisse eum in terra hominem, et virtutes perfecisse. Quapropter neque passsum eum, sed Simonem quendam Cyrenæum angariatum portasse crucem ejus pro eo: et hunc secundum ignorantiam et errorem crucifixum, transfiguratum ab eo, uti putaretur ipse esse Jesus: et ipsum autem Jesum Simonis accepisse formam, et stantem irrisisse eos." Book 1, Chapter 19

- ^ a b Joel L. Kraemer Israel Oriental Studies XII BRILL 1992 ISBN 9789004095847 p. 41

- ^ Lawson, Todd (1 March 2009). The Crucifixion and the Quran: A Study in the History of Muslim Thought. Oneworld Publications. p. 12. ISBN 978-1851686353.

- ^ Eddy, Paul Rhodes and Gregory A. Boyd (2007). The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. Baker Academic. p. 172. ISBN 0801031141. ...if there is any fact of Jesus' life that has been established by a broad consensus, it is the fact of Jesus' crucifixion.

- ^ Haer. 1.24.4

- ^ Kelhoffer, James A. (2014). Conceptions of "Gospel" and Legitimacy in Early Christianity. Mohr Siebeck. p. 80. ISBN 9783161526367.

- ^ Ayoub, Mahmoud M. (1980). "Towards an Islamic Christology, II:The Death of Jesus, Reality or Delusion". The Muslim World. 70 (2): 91–121. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.1980.tb03405.x. ISSN 0027-4909.

- ^ Reynolds, Gabriel Said (May 2009). "The Muslim Jesus: Dead or Alive?" (PDF). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London). 72 (2). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 237–258. doi:10.1017/S0041977X09000500. JSTOR 40379003. S2CID 27268737. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

Bibliography[edit]

- Roslan Abdul-Rahim (December 2017). "Demythologizing the Qur'an Rethinking Revelation Through Naskh al-Qur'an" (PDF). Global Journal Al-Thaqafah. 7 (2): 51–78. doi:10.7187/GJAT122017-2. ISSN 2232-0474. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- Bannister, Andrew G. "Retelling the Tale: A Computerised Oral-Formulaic Analysis of the Qur'an. Presented at the 2014 International Qur'an Studies Association Meeting in San Diego". academia.edu. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Burton, John (1990). The Sources of Islamic Law: Islamic Theories of Abrogation (PDF). Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-0108-2. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- Cook, Michael (2000). The Koran : A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192853449.

- Crone, Patricia (1987). Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam (PDF). Princeton University Press.

- Crone, Patricia; Cook, Michael (1977). HAGARISM, THE MAKING OF THE ISLAMIC WORLD (PDF). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Dashti, `Ali (1994). Twenty Three Years: A Study of the Prophetic Career of Mohammad (PDF). Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- Donner, Fred M. (2008). "The Quran in Recent Scholarship". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 29-50.

- Dundes, Alan (2003). Fables of the Ancients?: Folklore in the Qur'an. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9780585466774. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Gibb, H.A.R. (1953) [1949]. Mohammedanism : An Historical Survey (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Guillaume, Alfred (1978) [1954]. Islam. Penguin books.

- Hawting, G.R. (2000). "16. John Wansbrough, Islam, and Monotheism". The Quest for the Historical Muhammad. New York: Prometheus Books. pp. 489–509.

- Holland, Tom (2012). In the Shadow of the Sword. UK: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-53135-1. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- Ibn Warraq, ed. (2000). "2. Origins of Islam: A Critical Look at the Sources". The Quest for the Historical Muhammad. Prometheus. pp. 89–124.

- Ibn Warraq, ed. (2000). "1. Studies on Muhammad and the Rise of Islam". The Quest for the Historical Muhammad. Prometheus. pp. 15–88.</ref>

- Ibn Warraq (2002). Ibn Warraq (ed.). What the Koran Really Says : Language, Text & Commentary. Translated by Ibn Warraq. New York: Prometheus. pp. 23–106. ISBN 157392945X. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Ibn Warraq (1995). Why I Am Not a Muslim (PDF). Prometheus Books. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- Leirvik, Oddbjørn (27 May 2010). Images of Jesus Christ in Islam (2nd ed.). New York: Bloomsbury Academic; 2nd edition. pp. 33–66. ISBN 978-1441181602.

- Lippman, Thomas W. (1982). Understanding Islam : An Introduction to the Moslem World. New American Library.

- Lüling, Günter (1981). A Challenge to Islam for Reformation; Die Wiederentdeckung des Propheten Muhammad: eine Kritik am "christlichen" Abendland. Erlangen: Luling.</ref>

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said, ed. (2008). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge.

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said (2008). "Introduction, Quranic studies and its controversies". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 1-26.

- Donner, Fred M. (2008). "The Quran in Recent Scholarship". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 29-50.

- van Bladel, Kevin (2008). "The Alexander Legend in the Qur'an 18:83-102". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 175-203.

- Saadi, Abdul-Massih (2008). "Nascent Islam in the Seventh Century Syriac Sources". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 217-222.

- Böwering, Gerhard (2008). "Recent Research on the Construction of the Quran". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 70-87.

- Gillot, Claude (2008). "Reconsidering the Authorship of the Quran. Is the Quran party the fruit of a progressive and collective work?". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 88-108.

- Rodinson, Maxime (2002). Muhammad. London: Tauris Parke. ISBN 1-86064-827-4.

- Said, Edward (1978). Orientalism. Vintage. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- Wansbrough, John (2004). Quranic Studies : Sources and Methods of Scriptural Interpretation (PDF). Foreword, Translations, and Expanded Notes by Andrew Rippin. Amherst, New York: Prometheus. ISBN 1-59102-201-0. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- Weiss, Bernard (April–June 1993). "Reviewed Work: The Sources of Islamic Law: Islamic Theories of Abrogation by John Burton". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 113 (2): 304–306. doi:10.2307/603054. JSTOR 603054.

Category:Quran Category:7th-century books Category:Historicity of religion Category:Religious texts

END OF CURRENT VERSION

SECTION ON PROPOSED CHANGES

PROPOSED NEW NAMES FOR ARTICLE

Historical criticism of the Quran[edit]

Origin of the Quran according to academic historians[edit]

ORIGINAL LEAD

Historical reliability of the Quran concerns the question of the historicity of the described or claimed events in the Quran. Muslims have generally disapproved of the historical criticism of the Quran[1]. In the Muslim world, scholarly criticism of the Quran can be considered an apostasy and can be punished by death.[2] Scholarly criticism of the Quran, is thus, a beginning area of study.[3][4] Scholars have identified several pre-existing sources for the Quran.[5] The Quran assumes its readers' familiarity with the Christian Bible and there are many parallels between the Bible and the Quran. Aside from the Bible, the Quran includes legendary narratives about Alexander the Great, apocryphal gospels,[6] and Jewish legends. Thus, the question of the historical reliability of the Quran is tied to the question of the historical reliability of the Bible.

PROPOSED LEAD (to be added later)

Historical and scholarly criticism of the Quran (or secular Quranic studies) involves investigating and verifying the Quran's origin, text, composition, history,[7] in a manner similar to Biblical criticism[8] (and unrelated to criticism in the sense of "expressing disapproval"). Issues examined might include variations in text among different versions/manuscripts; the intended audience (such as whether the audience was assumed to be familiar with the Christian Bible); puzzles of unclear letters, words and phrases, unexplained by early exegetes; themes and stories found in other earlier texts[9] (such as narratives about Alexander the Great) and earlier religious works (especially the bible, apocryphal gospels and Jewish legends);[10] patterns and repetition of text suggesting oral transmission, etc.

Some Muslims have have found secular study of the Quran "disturbing and offensive",[7] "dangerous",[11] and even an "assault"[7] on the holy book, (and some Muslims have been punished for attempting it).[Note 1][15][16][Note 2] At least some have also found it superfluous,[19] as traditional Islamic religious sciences (`ulum ul-Qur'an) already provide "all the answers to questions posed by modern western orientalists" except those "that issue from the rejection" of the Quran's "Divine Origin".[20] Orthodox belief holds that the Quran is divine, perfect, and unchangeable, having been sent down by Allah (God) and revealed to Muhammad by the angel Jabreel (Gabriel).

Scholarly criticism of the Quran (as opposed to traditional Islamic study) is thus a relatively new area of study,[21][22] but has been practiced by secular, (mostly) Western scholars (such as John Wansbrough, Joseph Schacht, Patricia Crone, Michael Cook) who set aside doctrines of its divinity, perfection, unchangeability, etc. accepted by Muslim Islamic scholars;[7]

Historical and scholarly criticism of the Quran *variations in text among different versions/manuscripts; *the intended audience (such as whether the audience was assumed to be familiar with the Christian Bible); *puzzles of unclear letters, words and phrases, unexplained by early exegetes; *themes and stories found in other earlier texts[9] (such as narratives about Alexander the Great) and earlier religious works (especially the bible, apocryphal gospels and Jewish legends);[10] *patterns and repetition of text suggesting oral transmission, etc.

[proposed rewrite]

Questions about history and origins[edit]

Traditional history of Quran[edit]

According to Islamic narrative/historical tradition, the Quran -- bringing a message of uncompromising monotheism to humanity -- was passed down from its archetype[23]/prototype[24] in heaven.[Note 3] It was revealed to Muhammad, an illiterate Arab trader, in the pagan society and desert environment of Western Arabia over 22 years starting in 610 CE.[25][Note 4] As the Prophet of Islam -- and despite persecution of the pagan ruling class of his home town -- Muhammad built up a following many of whom wrote down his revelations and/or memorized them. From these memories and written scraps the Quran was carefully complied, edited and codified not long after Muhammad's death, under the supervision of Caliph Uthman (the third successor of Muhammad).[27] Islam spread as Arab Muslims, outnumbered but fired by religious conviction, conquered the Persian Sasanian Empire and most of the Byzantine empire. Seven copies of the standard codex edition of the Quran or "Muṣḥaf" were made and sent by Uthman to the major centers of this rapidly expanding empire.[28] All other incomplete or "imperfect" variant copies were destroyed. In the next few centuries, the religion and empire of Islam solidified, and a great body of religious literature and laws was developed, including commentaries/exegeses (Tafsir) to explain the Quran.

According to traditional Islamic teaching, we know that not only was the Quran "perfect, timeless", "absolute", revealed by God to Muhammad,[7] but that it has remained so to the present day,[29] both because of the careful work of pious Muslims and because of divine protection (indicated in this verse):[11]

Quran 15:9:

- إِنَّا نَحْنُ نَزَّلْنَا الذِّكْرَ وَإِنَّا لَهُ لَحَافِظُونَ

- "Indeed, it is We who sent down the Quran and indeed, We will be it's guardian."[11]

While there are mysteries in the Quran (and Islam in general), known only to God, God has revealed what we need to know.[Note 5]

- Secular Quranic studies

For some time, until the early 1970's,[32] most non-Muslim scholars — while not accepting the divinity of the Quran — did accept its origin story[33] "in most of its details".[34] Ernest Renan famously declared that "Islam was born, not amid the mystery which cradles the origins of other religions, but rather in the full light of history."[35]

But in recent years, secular scholars (such as Günter Lüling, John Wansbrough, Yehuda D. Nevo and Christoph Luxenberg),[36] have begun to question much of "what the Muslim historical tradition can tell us about the origins of Islam",[37] questioning, for example, the link between the Quran and the traditional beliefs about the life of Muhammad.[38]

Since historical criticism based on the scientific method does not accept divine revelation/intervention as an explanation nor refuse to study a subject on the grounds that human beings cannot understand or know it,[Note 6] it may question or contradict the Islamic historical tradition. Consequently "one of the most dangerous aspects of Orientalism was the European study of the origins of the Quran" (according to Firas Alkhateeb writing in "Lost Islamic History" posted in Islamicity website), [11] and part of "an attempt to obliterate the whole course of the history of Islam and existence of the Qurʾān during the first two centuries" (M. Feroz-ud-Din Shah Khagga and M. Mahmood Warraich)[42]

So far, however, answers to criticism questions have been in short supply. According to scholar Fred Donner, while it is generally agreed the Quran was intended as "a source of religious and moral guidance" for its readers, "we simply do not know ... things so basic"[34] about the Quran as

How did [it] originate? Where did it come from, and when did it first appear? How was it first written? In what kind of language was -- is -- it written? What form did it first take? Who constituted its first audience? How was it transmitted form one generation to another, especially in its early years? When, how and by whom was it codified?[34]

Problems with traditional history[edit]

Secondary evidence and textual history and their lack[edit]

In addressing the question of "when did the Quran first appear", traditional secular Quranic studies has been criticized for not challenging the received wisdom of Islamic historical tradition and failing to compare it to supporting evidence such as archaeological findings or non-Muslim literary sources.[43] What has been described as a "wave of skeptical scholars" or revisionists argued that the Islamic historical tradition had been greatly corrupted in transmission, and its account of the origin of the Quran should not be trusted. Skeptics argue that evidence suggests the Quran appeared later than Islamic historical tradition maintains, i.e. later than circa 650 CE.

Islamic historians Patricia Crone, Michael Cook, John Wansbrough, Fred Donner, and archaeologist Yehuda D. Nevo all argue that all the primary Islamic historical sources -- the "biographical, exegetical, jurisprudential and grammatical texts" known to modern scholars -- that the traditional history of the Quran is based on, are from 150–300 years after the events which they describe, leaving several generations for events to be forgotten, misinterpreted, garbled, embroidered on, etc.[44][45][46] Specifically, this leaves a gap of some decades between the traditional date for codification of the Quran (circa 650 CE) and when the "full light of history" began to shine (i.e. during the Abbasid Caliphate era starting 750 CE), according to historian John Wansbrough.[47]: 38

SEE IF YOU CAN PUT THIS SOMEWHERE ELSE

(Michael Cook wonders why the heavenly archetype of the Quran is a book, the Muṣḥaf Quran on Earth is a book, but between these came a revelation to Muhammad that was oral, piecemeal, and not in the same order as the book -- the verse first revealed to Muhammad reputed to be not Q.1:1 but Q.96[23] -- but mainly his concern was with other issues.)

Epigraphic (rock carvings), numismatic (coins of the era), archaeological evidence is lacking that mentions the Quran (and sometimes even Islam) before around 690, i.e. during the era when according to the traditional history, pious salafs ("The best of my community" according to a sahih hadith),[48] and rightly guided caliphs (Rashidun), should have been holding sway. Cook and Crone argue (as of 1999) that "there is no hard evidence for the existence of the Koran in any form before the last decade of the seventh century,"[49] about 40 year later than traditional Islamic history. Referring to the obscure words and phrases and the "mystery letters" and mystery of the Sabians in the Quran, Cook (and Christopher Rose) argue that "someone must once have known" what these mean, and that their meaning was forgotten now suggests the Quran may have been "off the scene for several decades".[50][51][28] (Pious Muslims argue that there are many things in Islam known only to God.)

The "earliest Arabic Islamic literary sources" of Islamic origins are the "biographical, exegetical, jurisprudential and grammatical texts written" during the Abbasid Caliphate, according to Fred Donner, leaving a gap of some decades between the traditional date for codification of the Quran and when the "full light of history" of the Abbasids shown, according to historian John Wansbrough (1928–2002).[47]: 38 (The claim that the Abbasid Islamic literary texts were simply transmitting earlier sources from the time of Muhammad has been questioned by another scholar, Ignác Goldziher).[52]

Archaeologist Nevo and researcher Judith Koren note coins of the region and era used Byzantine -- not Islamic -- iconography until the reign of Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (646-705 CE).[53][54]

Tradition tells us the Quran was composed in the early 7th century CE, but according to historian Tom Holland, "only in the 690's did a Caliph finally get around to inscribing the Prophet's name on a public monument; only decades after that did the first tentative references to him start to appear in private inscriptions".[55]

The earliest biographer whose complete work has survived is Ibn Hisham, who died in 833, 200 years after Muhammad.[Note 7] Of the victories over the Persian and Byzantine Empire of the first 200 years of the Islamic empire (futūḥ), "not a single record" has survived to this day. "Neither letters, nor speeches, nor journals, if they were ever so much as written, have survived; no hint as to what those who actually lived through the establishment of the Caliphate thought, or felt, or believed."[55] (In contrast, historical records were being written "even on the most barbarous fringes of civilisation" in Dark Ages era Britain.[57] One fragment of papyrus found that can be dated to a time relatively soon after the time of Muhammad (around 740 CE) and makes mention of a key event in the Islamic historical tradition (decisive victory of the Battle of Badr), contradicts the tradition -- indicating that the battle was not fought during Ramadan.[58][59]

Examining 7th century Byzantine Christian sources commentary on the Arab "immigrants" (Mhaggraye) who were invading/settling in formerly Byzantine territory at that time, historian Abdul-Massih Saadi found the Christians never mentioned the terms "Quran" nor "Islam" nor that the immigrants were of a new religion.[60][Note 8] The Christians used secular or political, not religious terms (kings, princes, rulers) to refer to the Arab leaders. Muhammad was "the first king of the Mhaggraye", also guide, teacher, leader or great ruler. They referred to the immigrants in ethnic terms -- "among them (Arabs) there are many Christians...".[61] They did however mention the religion of the Arabs. The immigrants' religion was described as monotheist "in accordance with the Old Law (Old Testament)".[60] When the Emir of the immigrants and Patriarch of the local Christians did have a religious colloquium there was much discussion of the scriptures but no mention of the Quran, "a possible indication that the Quran was not yet in circulation."[60] The Christians reported the Emir was accompanied by "learned Jews", that the immigrants "accepted the Torah just as the Jews and Samaritans", though none of the sources described the immigrants as Jews.[60] The Byzantine Christians did mention "First and Second Civil Wars" among "Arab political and tribal factions" which they saw as destroying the immigrants.[60]

(end of proposed version, so far)

it was insured that the wording of the Quranic text available today corresponds exactly to the literal, infallible,[62] "perfect, timeless", "absolute"[7] unadulterated word of God revealed to Muhammad.[63] That revelation in turn is identical to an eternal “mother of the book”[Note 9] the archetype[23]/prototype[24] of the Quran. This was not created/written by God, but an attribute of Him, co-eternal and kept with Him in heaven.[64][Note 10]

Textual history [Current first section][edit]

updating with Sinai-2014 is one sentence from ibn warraq

The Quran is believed to have had some oral tradition of passing down at some point. Differences that affected the meaning were noted, and around AD 650 Uthman began a process of standardization, presumably to rid the Quran of these differences. Uthman's standardization did not completely eliminate the textual variants.[65]

- Sanaa manuscript

DE-COPYRIGHTIZE

In the 1970s, 14,000 fragments of Quran were discovered in the Great Mosque of Sana'a in Yemen. The Sanaa manuscript is one of the oldest manuscripts of the Quran (carbon dating gives a 95% probability of parchment being produced between 578 CE and 669 CE)[66] It "exhibits frequent divergences from the canonical rasm," (5000+ according to Ibn Warraq)[67] "ranging from difference in the grammatical person of verbs and suffixed to the omission, addition, and transposition of words and brief phrases." .... it "also arranges the suras in a different order, although the order of verses within a given sura displays almost no deviation from the standard rasm."[68] Consequently the manuscript may be "the most serious rival of the traditional dating of the standard rasm would at present (2014) seem to the the hypothesis that the Quranic text, in spite of having achieved a recognizable form by 660, continued to be reworked and revised until c.700" which if true could be argued to suggest that "during the 60 or 70 years after Muhammad's death a significant reworking of his original preaching might have taken place."[66] p.276

About variant versions of the Quran in general German scholar Gerd R. Puin has said, "the existence of variant readings indicates that neither the oral tradition nor the [textual] context were strong enough to rule out the emergence of alternative readings."[69]

- Birmingham

In 2015, some of the earliest known Quranic fragments, dating from between approximately CE 568 and 645, were identified at the University of Birmingham.[70] Islamic scholar Joseph E. B. Lumbard of Hamad Bin Khalifa University has written in the Huffington Post in support of the dates proposed by the Birmingham scholars. Professor Lumbard notes that the discovery of a Qur'anic text that may be confirmed by radiocarbon dating as having been written in the first decades of the Islamic era, and includes variations in the “under text.” recorded in the Islamic historiographical tradition . [71] [unreliable source?]

- Dome of the Rock

The Dome of the Rock in the Old City of Jerusalem is (in its core) one of the oldest extant works of Islamic architecture,[72] and exhibits some of the earliest inscriptions of Quranic verses on copper plates and mosaics inside the building. Some of the verses are slightly different from the standard Quranic rasm (verses from Q.64.1 and 57.2 are conflated; a divine 1st person statement in Q 7:156 appears in 3rd person form, etc.) All this has suggested to historians such as Chase Robinson and Stephen J. Shoemaker that since the Dome was completed in 691/2 CE, and Muslims are not in the habit of making inscriptions of paraphrased verses from the Quran, "Quranic texts must have remained at least partially fluid through the late seventh and early eighth century".[73][74]

check for duplication in earlier rewrite

Traditional history of Quran[edit]

According to Islamic narrative/historical tradition, the Quran -- bringing a message of uncompromising monotheism to humanity -- was passed down from heaven and revealed to Muhammad, an illiterate Arab trader, by the the angel Gabriel (Jabreel), in the pagan society and desert environment of Western Arabia over 22 years starting in 610 CE.[25][Note 11] Muhammad became the Prophet of Islam, who despite persecution of the pagan ruling class, built up a following many of whom wrote down his revelations and/or memorized them. From these memories and written scraps the Quran was carefully complied, edited and codified under the supervision of Caliph Uthman (the third successor of Muhammad) not long after Muhammad's death.[27] Islam spread as Arab Muslims conquered the Persian Sasanian Empire and most of the Byzantine empire, fired by religious conviction. According to tradition, seven copies of the standard codex edition of the Quran or "Muṣḥaf" were made and sent to the major centers of this rapidly expanding empire,[28] and all other incomplete or "imperfect" variants of the Quranic revelation were destroyed, and the same Quran has been preserved and cherished by Muslims as ever since.[29] In the next few centuries, the religion and empire of Islam solidified, and an enormous body of religious literature and laws were developed, including hadith, commentaries/exegeses (Tafsir) to explain the Quran.

Thus, according to Islamic teaching, it was insured that the wording of the Quranic text available today corresponds exactly to the literal, infallible,[62] "perfect, timeless", "absolute"[7] unadulterated word of God revealed to Muhammad.[75] "Muslims believe that Allah has already promised to protect the Quran from the change and error that happened to earlier holy texts," quoting Quran 15:9:

- إِنَّا نَحْنُ نَزَّلْنَا الذِّكْرَ وَإِنَّا لَهُ لَحَافِظُونَ

- "Indeed, it is We who sent down the Quran and indeed, We will be it's guardian."[11]

That revelation in turn is identical to an eternal “mother of the book”[Note 12] the archetype[23]/prototype[24] of the Quran. This was not created/written by God, but an attribute of Him, co-eternal and kept with Him in heaven.[64][Note 13]

Scholars have identified several pre-existing sources for the Quran.[76] The Quran assumes its readers' familiarity with the Christian Bible and there are many parallels between the Bible and the Quran. Aside from the Bible, the Quran includes legendary narratives about Alexander the Great, apocryphal gospels,[77] and Jewish legends. Thus, the question of the historical reliability of the Quran is tied to the question of the historical reliability of the Bible.

The Quran is viewed to be the scriptural foundation of Islam and is believed by Muslims to have been been sent down by Allah (God) and revealed to Muhammad by the angel Jabreel (Gabriel). Scholarly study or historical criticism of the Quran by secular, (mostly) Western scholars (such as John Wansbrough, Joseph Schacht, Patricia Crone, Michael Cook) who set aside doctrines of its divinity, perfection, unchangeability, etc. accepted by Muslim Islamic scholars;[7] to investigate and verify the Quran's origin, text, composition, history,[7] examining questions, puzzles, difficult text, etc.

(REWRITE THat last SENTENCE WITH SUMMARY OF CRITICISMS)

Many Muslims find not only the religious fault-finding but also Western scholarly investigation of textual evidence "disturbing and offensive".[7]

Background[edit]

Traditional Islamic view of Quran[edit]

(USED in Quranic text)

According to Islamic tradition, which criticism may question or contradict, the Quran followed a passage from heaven down to the angel Gabriel (Jabreel) who revealed it in the seventh century CE over 23 years to an Hejazi Arab trader, Muhammad, who became the Prophet of Islam.[25][Note 14]

Muhammad shared these revelations -- which brought uncompromising monotheism to humanity -- with his companions who wrote them down and/or memorized them. From these memories and scraps a standard edition was carefully complied and edited under the supervision of Caliph Uthman not long after Muhammad's death.[27]

Copies of this codex or "Mus'haf" were sent to the major centers of what was by this time a rapidly expanding empire, and all other incomplete or "imperfect" variants of the Quranic revelation were destroyed. In the next few centuries, the religion and empire of Islam solidified, and an enormous body of religious literature and laws were developed, including commentaries/exegeses (Tafsir) to explain the Quran.

(USED in Quranic text)

Thus, according to Islamic teaching, it was insured that the wording of the Quranic text available today corresponds exactly to the literal, infallible,[62] "perfect, timeless", "absolute"[7] unadulterated word of God revealed to Muhammad.[78] That revelation in turn is identical to an eternal “mother of the book”[Note 15] the archetype[23]/prototype[24] of the Quran. This was not created/written by God, but an attribute of Him, co-eternal and kept with Him in heaven.[64][Note 16]

(USED Questions about Quranic text)

The Quran itself states that its revelations are themselves "miraculous 'signs'"[62] -- inimitable (I'jaz) in their eloquence and perfection[79] and proof of the authenticity of Muhammad's prophethood.

[Note 17]

Several verses remark on how the verses of the book set clear or make things clear,[Note 18] and are in "pure and clear" Arabic language [Note 19]

At the same time, (most Muslims believe) some verses of the Quran have been abrogated (naskh) by others and these and other verses have sometimes been revealed in response or answer to questions by followers or opponents.[64][83][84]

NOT USED

In contrast, Muslim consider the contents of the Quran "are a source of doctrine, law, poetic and spiritual inspiration, solace, zeal, knowledge, and mystical experience."[85] "Millions and millions" of Muslims "refer to the Koran daily to explain their actions and to justify their aspirations",[Note 20] and in recent years many consider it the source of scientific knowledge.[86][87] Revered by pious Muslims as "the holy of holies",[88] whose sound moves some to "tears and esctasy",[89] it is the physical symbol of the faith,[85] the text often used as a charm[90] on occasions of birth, death, marriage. Consequently, "It must never rest beneath other books, but always on top of them, one must never drink or smoke when it is being read aloud, and it must be listened to in silence. It is a talisman against disease and disaster.[88][91]

The monotheist oneness of God; Judgement Day and the delights of paradise that await believers and torments of hell that await those who have rejected God's word are described in repeatedly and in detail.[92]

As in the bible, God reveals his will to humanity through prophets — such as Abraham, Moses and Jesus — bringing holy books. Unlike the bible, it is (thought to be) not simply divinely inspired, but the literal word of God;[93] the last and complete message from God, from his final messenger (Muhammad)[94] superseding the Old and New Testament and purified of "accretions of Judaism and Christianity".[95][96] It has been called "the Word of God made text", the Islamic equivalent not of the bible but of Jesus Christ — "the Word of God made flesh".[7][97][98]

Slightly shorter than the New Testament,[99] it is organized in 114 "surahs" or chapters — not according to when they were revealed (nor by subject matter), but according to length of surahs (with some exceptions) under the guidance of divine revelation.[25]

Revered by pious Muslims as "the holy of holies",[88] whose sound moves some to "tears and esctasy",[89] it is the physical symbol of the faith,[85] the text often used as a charm[100] on occasions of birth, death, marriage. Consequently

It must never rest beneath other books, but always on top of them, one must never drink or smoke when it is being read aloud, and it must be listened to in silence. It is a talisman against disease and disaster.[88][91]

Traditionally great emphasis was put on children memorizing the 6200+ verses of the Quran, those succeeding being honored with the title Hafiz. "Millions and millions" of Muslims "refer to the Koran daily to explain their actions and to justify their aspirations",[Note 21] and in recent years many consider it the source of scientific knowledge.[86][87]

History and Context[edit]

Devotion of believers[edit]

For Muslims the contents of the Quran have been "a source of doctrine, law, poetic and spiritual inspiration, solace, zeal, knowledge, and mystical experience."[85] "Millions and millions" of whom "refer to the Koran daily to explain their actions and to justify their aspirations",[Note 22] and in recent years many consider it the source of scientific knowledge.[86][87] Revered by pious Muslims as "the holy of holies",[88] whose sound moves some to "tears and esctasy",[89] it is the physical symbol of the faith,[85] the text often used as a charm[101] on occasions of birth, death, marriage. Consequently, "It must never rest beneath other books, but always on top of them, one must never drink or smoke when it is being read aloud, and it must be listened to in silence. It is a talisman against disease and disaster."[88][91] Unlike the bible, it is (thought to be) not simply divinely inspired, but the literal word of God;[93] the last and complete message from God, from his final messenger (Muhammad)[94] superseding the Old and New Testament and purified of "accretions of Judaism and Christianity".[95][96]

Islamic Quranic Sciences[edit]

Muslims have developed their own Quranic studies or "Quranic sciences" (‘ulum al Qur’an)[102] over the centuries,[20] following the Quranic encouragement "Will they not contemplate the Quran?"(4:82).[38] There are two types of exegesis to explain and interpret the Quran: tafsir (literal interpretation) and ta’wil (allegorical interpretation). Other issues studied are kalimat dakhila (the investigation of the foreign origin of some Quranic terms);[103] naskh (studying contradictory verses[Note 23] to determine which should be abrogated in favor of the other), study of "occasions of revelation" (connecting Quranic verses with "episodes of Muhammad's career based on hadith and biographies of him -- which are known as sira), chronology of revelation,[102] the division of quranic chapters (surahs) into "Meccan surah" (those believed to have been revealed in Mecca before the hijra) and "Medinan surah (revealed afterward in the city of Medina).[104] According to Seyyed Hossein Nasr, these traditional religious sciences

"provide all the answers to questions posed by modern western orientalists about the structure and text of the Koran, except, of course, those questions that issue from the rejection of the Divine Origin of the Koran and its reduction to a work by the prophet. Once the revealed nature of the Koran is rejected, then problems arise. But these are problems of orientalist that arise not from scholarship but from a certain theological and philosophical position that is usually hidden under the guise of rationality and objective scholarship. For Muslims there has never been the need to address these 'problems' ..."[20]

- History of Western scholarship of Quran

In contrast, many of the original non-Muslim scholars of the Quran worked "in the context of an openly declared hostility" between Christianity and Islam, with an eye to debunking Islam or proselytizing against it.[7] The nineteenth-century orientalist and colonial administrator William Muir, wrote that the Quran was one of "the most stubborn enemies of Civilisation, Liberty, and the Truth which the world has yet known."[105] In the twentieth century, scholars of the early Soviet Union working in the context of dialectical materialism and fighting the "opium of the people" went on about how Muhammad and the first Caliphs were "mythical figures" and that "the motive force" of early Islam was "the mercantile bourgeoisie of Mecca and Medina" and "slave-owning" Arab society.[106]

At least one scholar argues that Biblical criticism -- the idea that "the Bible be read in the same way as other literature" -- emerged from Medieval Quranic criticism, which in its origins was not dispassionate, culturally sensative work but motivated by the hope of proving "that the Quran was not divine revelation". [107]

Not all non-Muslim scholars of Islam are interested in critical examination/analysis. Patricia Crone and Ibn Rawandi argue that Western scholarship lost its critical attitude to the sources of the origins of Islam around the time of the First World War." Andrew Rippin has found a number of students that expressed surprise "at the lack of critical thought that appears in introductory textbooks on Islam" ...

students acquainted with approaches such as source criticism, oral-formulaic composition, literary analysis and structuralism, all quite commonly employed in the study of Judaism and Christianity, ... who express surprise

such naive historical study seems to suggest that Islam is being approached with less than academic candor.[108]

Scholars have complained about "'dogmatic Islamophilia' of most Arabists" (Karl Binswanger);[109] that in one western country (France as of 1983) "it is no longer acceptable to criticize Islam or the Arab countries" (Jacque Ellul);[110] that "understanding has given way to apologetics pure and simple" (Maxime Rodinson complaining about historians "like Norman Daniel").[111][112]

Current hostility by Muslims to criticism[edit]

At least in part in reaction, some Muslim opposition to "The Orientalist enterprise of Qur'anic studies" has been intense.[7] In 1987 Muslim critic S. Parvez Manzoor, denounced it as conceived in "the polemical marshes of medieval Christianity".

At the greatest hour of his worldly-triumph, the Western man, coordinating the powers of the State, Church and Academia, launched his most determined assault on the citadel of Muslim faith. All the aberrant streaks of his arrogant personality—its reckless rationalism, its world-domineering phantasy and its sectarian fanaticism—joined in an unholy conspiracy to dislodge the Muslim Scripture from its firmly entrenched position as the epitome of historic authenticity and moral unassailability.[113]

In recent twenty first century, some Muslim Islamic scholars have warned against lending "legitimacy to non-Muslim scholars’ understanding about Islam" by engaging with them, and that even a rigorously scholarly academic work on Islam such as the Brill Encyclopedia of Islam "is filled with insults and disparaging remarks about the Qur’an".[114]

Textual criticism of the Quran, the structure and style of the surahs, has been opposed on grounds that it questions the divine origin of the Quran.[25] Seyyed Hossein Nasr has denounced the “rationalist and agnostic methods of higher criticism” as similar to dissecting and subjecting Jesus to “modern medical techniques” to determine whether he was born miraculously or was the son of Joseph,[115][86][7] In his influential Orientalism, Edward Said declared Western study of the Middle East — including the religion of Islam — inextricably tied to Western Imperialism, making the study inherently political and servile to power.[116]

- Reply

These complaints have been compared to those of other religious conservatives (Christian) against textual historical criticism of their own sacred text (the bible).[Note 24] Non-Muslim scholar Patricia Crone acknowledges the call for humility towards the sacred of other cultures — "who are you to tamper with their legacy?" — but defends challenging of orthodox views of Islamic history, saying "we Islamicists are not trying to destroy anyone's faith."[7]

- Examples of retribution

Not all Muslims oppose criticism; Roslan Abdul-Rahim writes that critical study of the Quran "will not hurt the Muslims; it will only help them" because "no amount of criticism can change that fact" that the "Quran is truly a divine piece of work as the Muslim theology stipulates and as the Muslims have so strongly defended".[117] But among those who have suffered in the process of attempting to apply literary or philological techniques to the Quran are Egyptian "Dean of Arabic Literature" Taha Husain (lost his post at Cairo University in 1931),[Note 25] Egyptian professor Mohammad Ahmad Khalafallah (dissertation rejected),[15][16] a non-Muslim German professor Günter Lüling (dismissed),[119][16] and perhaps most notably Egyptian professor Nasr Abu Zaid (forced to seek exile in Europe after being declared an apostate and threatened with death for violating a "right of God").[Note 26]

Questions about history and origins[edit]

Textual history [Current first section][edit]

The Quran is believed to have had some oral tradition of passing down at some point. Differences that affected the meaning were noted, and around AD 650 Uthman began a process of standardization, presumably to rid the Quran of these differences. Uthman's standardization did not completely eliminate the textual variants.[120]

In the 1970s, 14,000 fragments of Quran were discovered in the Great Mosque of Sana'a, the Sana'a manuscripts. About 12,000 fragments belonged to 926 copies of the Quran, the other 2,000 were loose fragments. The oldest known copy of the Quran so far belongs to this collection: it dates to the end of the 7th–8th centuries.

The German scholar Gerd R. Puin has been investigating these Quran fragments for years. His research team made 35,000 microfilm photographs of the manuscripts, which he dated to early part of the 8th century. Puin has not published the entirety of his work, but noted unconventional verse orderings, minor textual variations, and rare styles of orthography. He also suggested that some of the parchments were palimpsests which had been reused. Puin believed that this implied an evolving text as opposed to a fixed one.[121]

In 2015, some of the earliest known Quranic fragments, dating from between approximately AD 568 and 645, were identified at the University of Birmingham.[122] Islamic scholar Joseph E. B. Lumbard of Hamad Bin Khalifa University has written in the Huffington Post in support of the dates proposed by the Birmingham scholars. Professor Lumbard notes that the discovery of a Qur'anic text that may be confirmed by radiocarbon dating as having been written in the first decades of the Islamic era, and includes variations in the “under text.” recorded in the Islamic historiographical tradition . [123] [unreliable source?]

Traditional history of Quran[edit]

According to Islamic narrative/historical tradition, the Quran -- bringing a message of uncompromising monotheism to humanity -- was passed down from heaven and revealed to Muhammad, an illiterate Arab trader, by the the angel Gabriel (Jabreel), in the pagan society and desert environment of Western Arabia over 22 years starting in 610 CE.[25][Note 27] Muhammad became the Prophet of Islam, who despite persecution of the pagan ruling class, built up a following many of whom wrote down his revelations and/or memorized them. From these memories and written scraps the Quran was carefully complied, edited and codified under the supervision of Caliph Uthman (the third successor of Muhammad) not long after Muhammad's death.[27] Islam spread as Arab Muslims conquered the Persian Sasanian Empire and most of the Byzantine empire, fired by religious conviction. According to tradition, seven copies of the standard codex edition of the Quran or "Muṣḥaf" were made and sent to the major centers of this rapidly expanding empire,[28] and all other incomplete or "imperfect" variants of the Quranic revelation were destroyed, and the same Quran has been preserved and cherished by Muslims as ever since.[29] In the next few centuries, the religion and empire of Islam solidified, and an enormous body of religious literature and laws were developed, including hadith, commentaries/exegeses (Tafsir) to explain the Quran.

Thus, according to Islamic teaching, it was insured that the wording of the Quranic text available today corresponds exactly to the literal, infallible,[62] "perfect, timeless", "absolute"[7] unadulterated word of God revealed to Muhammad.[124] That revelation in turn is identical to an eternal “mother of the book”[Note 28] the archetype[23]/prototype[24] of the Quran. This was not created/written by God, but an attribute of Him, co-eternal and kept with Him in heaven.[64][Note 29]

Historical criticism may question or contradict the Islamic historical tradition, and according to Firas Alkhateeb (writing in "Lost Islamic History" posted in Islamicity website), "one of the most dangerous aspects of Orientalism was the European study of the origins of the Quran."[11] "Muslims believe that Allah has already promised to protect the Quran from the change and error that happened to earlier holy texts," quoting Quran 15:9:

- إِنَّا نَحْنُ نَزَّلْنَا الذِّكْرَ وَإِنَّا لَهُ لَحَافِظُونَ

- "Indeed, it is We who sent down the Quran and indeed, We will be it's guardian."[11]

Until the early 1970's,[32] non-Muslim scholars — while not accepting the divinity of the Quran — did accept its origin story[33] "in most of its details".[34] Ernest Renan famously declared that "Islam was born, not amid the mystery which cradles the origins of other religions, but rather in the full light of history."[35]

But in recent years secular scholars (such as Günter Lüling, John Wansbrough, Yehuda D. Nevo and Christoph Luxenberg)[36] have begun to question much of "what the Muslim historical tradition can tell us about the origins of Islam",[37][125] specifically questioning the link between the Quran and the traditional beliefs about the life of Muhammad.[38]

Those Quranic studies scholars doubting the traditional Islamic history of the Quran point to the lack of supporting historical evidence for the Islamic historical tradition's date of canonization of the Quran. This includes the lack of mention of the "Quran" nor "Islam",[60] nor "rightly guided caliphs", nor any of the famous futūḥ battles by Christian Byzantines in their historical records describing the Arab invaders advance, leaders or religion; the lack of any surviving documents by those Arabs who "lived through the establishment of the Caliphate";[55] the fact that coins of the region and era did not use Islamic iconography until sometime after 685 CE.[126][54] Evidence to suggest there was a break in the transmission of the knowledge of the meaning of much of the Quran not accounted for by Islamic historical tradition (a break somewhere after the time of the Qurans's revelation and before it's earliest commentators) includes the mystery letters and unintelligible words and phrases mentioned above.

Academic scholars who support "the position of the classical Islamic tradition that the Quran as it exists today is a seventh-century document,” point to the carbon dating of parchment and infrared photography of original ink of palimpsest parchment of the Birmingham Quran manuscript[127] to the time of Muhammad,[127] which "render[s] the vast majority of Western revisionist theories regarding the historical origins of the Quran untenable."[128]

Problems with traditional history[edit]

Secondary evidence and textual history and their lack[edit]

The traditional secular Quranic studies has been criticised for not challenging the received wisdom of Islamic historical tradition and lacking supporting evidence such as archaeological findings or non-Muslim literary sources.[43] What has been described as a "wave of sceptical scholars" (later known as the revisionist school of Islamic studies) argued that the Islamic historical tradition had been greatly corrupted in transmission. They tried to correct or reconstruct the early history of Islam from other, presumably more reliable, sources (i.e. secondary archaeological and textual evidence) — such as archaeological coins, inscriptions, and non-Islamic sources[47]: 23 — to address the question "when did the Quran first appear". They argue that evidence suggests it appeared later than Islamic historical tradition maintains, i.e. later than circa 650 CE.

Islamic historians Patricia Crone, Michael Cook, John Wansbrough, and archaeologist Yehuda D. Nevo all argue that all the primary Islamic historical sources which exist are from 150–300 years after the events which they describe, leaving several generations for events to be forgotten, misinterpreted, distorted, garbled, etc.[129][130][131] (Michael Cook wonders why the heavenly archetype of the Quran is a book, the Muṣḥaf Quran on Earth is a book, but between these came a revelation to Muhammad that was oral, piecemeal, and not in the same order as the book -- the verse first revealed to Muhammad reputed to be not Q.1:1 but Q.96[23] -- but mainly his concern was with other issues.)

Cook and Crone argue (as of 1999) that "there is no hard evidence for the existence of the Koran in any form before the last decade of the seventh century,"[49] about 40 year later than traditional Islamic history. Referring to the obscure words and phrases and the "mystery letters" and mystery of the Sabians in the Quran, Cook (and Christopher Rose) argue that "someone must once have known" what these mean, and that their meaning was forgotten now suggests the Quran may have been "off the scene for several decades".[50][132][28] (Pious Muslims argue that there are many things in Islam known only to God.)

The "earliest Arabic Islamic literary sources" of Islamic origins are the "biographical, exegetical, jurisprudential and grammatical texts written" during the Abbasid Caliphate, according to Fred Donner, leaving a gap of some decades between the traditional date for codification of the Quran and when the "full light of history" of the Abbasids shown, according to historian John Wansbrough (1928–2002).[47]: 38 (The claim that the Abbasid Islamic literary texts were simply transmitting earlier sources from the time of Muhammad has been questioned by another scholar, Ignác Goldziher).[52]

Archaeologist Nevo and researcher Judith Koren note coins of the region and era used Byzantine -- not Islamic -- iconography until the reign of Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (646-705 CE).[53][54]

Tradition tells us the Quran was composed in the early 7th century CE, but according to historian Tom Holland, "only in the 690's did a Caliph finally get around to inscribing the Prophet's name on a public monument; only decades after that did the first tentative references to him start to appear in private inscriptions".[55] The earliest biographer whose complete work has survived is Ibn Hisham, who died in 833, 200 years after Muhammad.[Note 30] Of the victories over the Persian and Byzantine Empire of the first 200 years of the Islamic empire (futūḥ), "not a single record" has survived to this day. "Neither letters, nor speeches, nor journals, if they were ever so much as written, have survived; no hint as to what those who actually lived through the establishment of the Caliphate thought, or felt, or believed."[55] (In contrast, historical records were being written "even on the most barbarous fringes of civilisation" in Dark Ages era Britain.[57] One fragment of papyrus found that can be dated to a time relatively soon after the time of Muhammad (around 740 CE) and makes mention of a key event in the Islamic historical tradition (decisive victory of the Battle of Badr), contradicts the tradition -- indicating that the battle was not fought during Ramadan.[58][59]

Examining 7th century Byzantine Christian sources commentary on the Arab "immigrants" (Mhaggraye) who were invading/settling in formerly Byzantine territory at that time, historian Abdul-Massih Saadi found the Christians never mentioned the terms "Quran" nor "Islam" nor that the immigrants were of a new religion.[60][Note 31] The Christians used secular or political, not religious terms (kings, princes, rulers) to refer to the Arab leaders. Muhammad was "the first king of the Mhaggraye", also guide, teacher, leader or great ruler. They referred to the immigrants in ethnic terms -- "among them (Arabs) there are many Christians...".[61] They did however mention the religion of the Arabs. The immigrants' religion was described as monotheist "in accordance with the Old Law (Old Testament)".[60] When the Emir of the immigrants and Patriarch of the local Christians did have a religious colloquium there was much discussion of the scriptures but no mention of the Quran, "a possible indication that the Quran was not yet in circulation."[60] The Christians reported the Emir was accompanied by "learned Jews", that the immigrants "accepted the Torah just as the Jews and Samaritans", though none of the sources described the immigrants as Jews.[60] The Byzantine Christians did mention "First and Second Civil Wars" among "Arab political and tribal factions" which they saw as destroying the immigrants.[60]

Nevo and Koren argue early Christian sources do not mention the "rightly guided caliphs" nor any of the famous futūḥ battles (i.e. the early Arab-Muslim conquests which facilitated the spread of Islam and Islamic civilization).[53][54]

Cook and Crone believe hints from the Quran are more reliable the narrative of tafsir, sira and hadith and that (as mentioned above) they believe the evidence from the Quran indicates an area around the south Dead Sea and not Mecca and Medina of Hijaz were the area Muhammad lived in. Wansbrough claims that Islamic traditions were often created (i.e. fabricated) "to demonstrate the Hijazi origins of Islam."[133]

Michael Cook argues Jerusalem, not Mecca, is the geographic focus of Muhammad's religious movement rather than just the area Muslims first expanded into after establishing control of Mecca. Cook cites an Armenian chronicler of the era who writes that Muhammad told the Arabs that "as descendants of Abraham through Ishmael, they too had a claim" to Palestine, which "God had promised the to Abraham and his seed".[134]

Scholar Gerd R. Puin claims that 20% of the Quran "simply doesn't make sense" and thinks this one fifth could not have been "understood even at the time of Muhammad".[7]

Also problematic is the reliability of isnads, i.e. the chains of people who transmitted a hadith from Muhammad to when it was collected by a compiler (such as Muhammad al-Bukhari, or Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj), and have been an important part of evidence for dating the Quran from the time of Muhammad.[135] But as mentioned above, the phenomenon of commentaries on Islamic history becoming larger and more informative the farther away they were from the time they wrote about does not inspire confidence in their historical accuracy;[136] and according to Stephen Humphreys, while a number of "very capable" modern scholars defended the general authenticity of isnads, most modern scholars regard isnads with "deep suspicion".[137]

The Quran is the highest ranking source of sharia (Islamic law), according to Islamic teaching, but some aspects of sharia seem to ignore or contradict the Quran. The most notable example of this conflict is that the traditional, universally accepted punishment for zina (adultery) under sharia was stoning to death (rajm), yet Michael Cook point out that the Quran clearly states the perpetrators should be given 100 lashes and says nothing about stoning.

- 24:2 — The [zina committing] woman or [zina committing] man found guilty of sexual intercourse — lash each one of them with a hundred lashes.[50]

An earlier Western scholar, Joseph Schacht, also noted that Sharia "often diverged from the intentions and even the explicit wording of the Koran", and that his evidence showed the law "did not derive directly from the Koran but developed ... out of popular and administrative practice under the Umayyads" (661-750 CE). "Norms derived from the Koran were introduced into Muhammadan law [i.e. sharia] almost invariably at a secondary stage."[138]

- Questions of Quranic studies

According to scholar Fred Donner, while it is generally agreed the Quran was intended as "a source of religious and moral guidance" for its readers, "we simply do not know ... things so basic"[34] about the Quran as

How did [it] originate? Where did it come from, and when did it first appear? How was it first written? In what kind of language was -- is -- it written? What form did it first take? Who constituted its first audience? How was it transmitted form one generation to another, especially in its early years? When, how and by whom was it codified?[34]

- Was there is "some kind of original version" of the Quran ("Ur-Quran") that today's Quran can "be traced back to"? or was the Quran created gradually, eventually "crystallizing"?

The Islamic historical tradition says there was an original version, which is the same as the current Mus'haf.[139] Traditionally Orientalist scholars also thought there was an original version, though they thought it was possible that "minor" changes may developed between the Ur-Quran and the Mus'haf.[139] Revisionists such as Günter Lüling and John Burton also agree that there was a "prototype text", though Lüling does not think it is from the time of Muhammad. Disagreeing are John Wansbrough[140][141] and his "followers" such as Andrew Rippin and G. R. Hawting who believe the Quran was "pieced together" over two centuries "or more" in a "long slow process of crystallization".[139]

- Where did it come from?

Mecca and then Medina in the Hijaz according to tradition. Wansbrough thinks it was in Abbasid Mesopotamia.[142][52] Crone and Cook and Tom Holland believe the Quran's mention of closeness to the remains of Lot's people (Q.37:137-8) and wheat, grapes and olives crops indicate southern Palestine.[43]

- If there was an original version, what was its "nature"? Christian? Jewish? Oral? some combination?

A source of religious and moral guidance for its audience, but was it Islam as we know it today? Abraham Geiger,[143]C.C. Torrey,[144] argued for a Jewish nature. Tor Andræ and Günter Lüling saw Christianity influencing Islam.[145][146] Andrew G. Bannister has asked whether the Quran was not just recited by believers but "composed orally", due to its resemblance to orally transmitted literature like epic poems.[147][148]

- "What "kind of language did it represent? And what was the relationship between the written text and that language?" The same Quranic Arabic written and spoken today? Or one of the Arab dialects? poetic Koiné Arabic? Or Arabic combined with Syriac?

The Islamic historical tradition says Arabic, but was it instead "a purely literary vehicle" not intended to represent the sound of a spoken language (like hànzì characters of Chinese)? Did it reflect the dialect of the Quraysh tribe? poetic Koiné language of the Bedouin?[149] Or a mixture of Arabic and an earlier language of Syriac?[150]

- "How was it transmitted?" Both orally and in writing? Or was oral transmission lost for a period of time?[151]

By written notes and oral recitation with nothing lost or added in the recension process (nothing that God did not want lost at least) according to the Islamic historical tradition. But could was there have been editing to completely transform the Ur-Quran?[152] And could it (or parts of it) have been transmitted only by written form at some stage in its history? (see: Possible written without oral transmission below)

- "How and when did codification and canonization of the Quran take place?" codification a couple of decades after canonization? More than a century later? At the same time?[153]

Canonized, i.e. given authority in the Muslim community from the very beginning, but codified into the Muṣẖaf with the "Uthmanic recession" in the mid 7th century CE, according to historical tradition. John Wansbrough says much later -- 200 + years after Muhammad;[154] John Burton believes earlier than tradition, upon Muhammad's death.[155][156][157]

Preexisting sources[edit]

- Quran and History [existing section

Creation narrative and the Flood [existing subsection][edit]

The Quran contains a creation narrative and refers to the world being created in six days. In Sūrah al-Anbiyāʼ, the Quran states that "the heavens and the earth were of one piece" before being parted.[158] God then created the landscape of the earth, placed the sky above it as a roof, and created the day and night cycles by appointing an orbit for both the sun and moon.[159] Some Muslim apologists, like Zakir Naik and Adnan Oktar advocate creationism. Some British Muslim students have distributed leaflets on campus, advocating against Darwin's theory of evolution[160] and contemporary Islamic scholar Yasir Qadhi believes that the idea that humans evolved is against the Quran.[161] It has to be noted, however, that not all Muslims are against the theory of evolution. Evolution is taught in many Islamic countries, and some scholars have tried to reconcile the Quran and evolution.[162]

Quran also contains the flood narrative. According to the Quran, Noah was a prophet for 950 years[163], and he built an ark where he filled it with pairs of animals.[164] People who did not believe him, including one of his own sons, are said to have drowned.[165]

Samiri [existing subsection][edit]

Quran recounts a story of the golden calf, where it mentions that Samiri, a rebellious follower of Moses, created the calf while Moses was away for 40 days on Mount Sinai, receiving the Ten Commandments.[166] Due to the fact that as-Samiri can mean the Samaritan,[167] some believe that his character is a reference to the worship of the golden calves built by Jeroboam of Samaria, conflating the two idol-worshiping incidents into one.

Alexander the Great legends [existing subsection][edit]

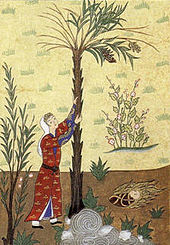

Quran also employs popular legends about Alexander the Great called Dhul-Qarnayn ("he of the two horns") in the Quran. The story of Dhul-Qarnayn has its origins in legends of Alexander the Great current in the Middle East in the early years of the Christian era. According to these the Scythians, the descendants of Gog and Magog, once defeated one of Alexander's generals, upon which Alexander built a wall in the Caucasus mountains to keep them out of civilised lands (the basic elements are found in Flavius Josephus). The legend went through much further elaboration in subsequent centuries before eventually finding its way into the Quran through a Syrian version.[168]

The reasons behind the name "Two-Horned" are somewhat obscure: the scholar al-Tabari (839-923 CE) held it was because he went from one extremity ("horn") of the world to the other,[169] but it may ultimately derive from the image of Alexander wearing the horns of the ram-god Zeus-Ammon, as popularised on coins throughout the Hellenistic Near East.[170] The wall Dhul-Qarnayn builds on his northern journey may have reflected a distant knowledge of the Great Wall of China (the 12th century scholar al-Idrisi drew a map for Roger of Sicily showing the "Land of Gog and Magog" in Mongolia), or of various Sassanid Persian walls built in the Caspian area against the northern barbarians, or a conflation of the two.[171]

Dhul-Qarneyn also journeys to the western and eastern extremities ("qarns", tips) of the Earth.[172] In the west he finds the sun setting in a "muddy spring", equivalent to the "poisonous sea" which Alexander found in the Syriac legend. [173] In the Syriac original Alexander tested the sea by sending condemned prisoners into it, but the Quran changes this into a general administration of justice.[173] In the east both the Syrian legend and the Quran have Alexander/Dhul-Qarneyn find a people who live so close to the rising sun that they have no protection from its heat.[173]

"Qarn" also means "period" or "century", and the name Dhul-Qarnayn therefore has a symbolic meaning as "He of the Two Ages", the first being the mythological time when the wall is built and the second the age of the end of the world when Allah's shariah, the divine law, is removed and Gog and Magog are to be set loose.[174] Modern Islamic apocalyptic writers, holding to a literal reading, put forward various explanations for the absence of the wall from the modern world, some saying that Gog and Magog were the Mongols and that the wall is now gone, others that both the wall and Gog and Magog are present but invisible.[175]

Death of Jesus [existing subsection][edit]