User:Kdtbhl/sandbox

Below you'll find a parts of pages I'm working on revisiting and editing.

Vowel harmony[edit]

Finnish, like many other Uralic languages, has vowel harmony, which restricts the cooccurrence of vowels belonging to different articulatory classes within a word. In Finnish, there are two classes of harmonizing vowels (which are distinguished by backness): {a, o, u} and {ä, ö, y}. No native non-compound word has vowels drawn from both groups.[1] For example, while words like talo and pyhä are allowable since they do not mix vowels from the two classes, a word like *talö could not be a native Finnish word.

Vowel harmony affects inflectional suffixes and derivational suffixes, which have two forms, one for use with back vowels, and the other with front vowels. Compare, for example, the following pair of abstract nouns: hallitus 'government' (from hallita, 'to reign') versus terveys 'health' (from terve, healthy).

Finnish has two vowels (/i/ and /e/) which lack back counterparts. These vowels are neutral with respect to vowel harmony in the sense that they may co-occur with the vowels of either of the aforementioned classes.[2] In Therefore, words like kello 'clock' (with a front vowel in a non-final syllable) and tuuli 'wind' (with a front vowel in the final syllable), which contain /i/ or /e/ together with a back vowel, count as back vowel words; /i/ and /e/ Kello and tuuli yield the inflectional forms kellossa 'in a clock' and tuulessa 'in a wind'. In words containing only neutral vowels, front vowel harmony is used, e.g. tie – tiellä ('road' – 'on the road'). For another, compound words do not have vowel harmony across the compound boundary;[3] e.g. seinäkello 'wall clock' (from seinä, 'wall' and kello, 'clock') has back /o/ cooccurring with front /æ/. In the case of compound words, the choice between back and front suffix alternants is determined by the immediately-preceding element of the compound; e.g. 'in a wall clock' is seinäkellossa, not *seinäkellossä.

A particular exception appears in a standard Finnish word, tällainen ('this kind of'). Although by definition a singular word, it was originally a compound word that transitioned over time to a more compact and easier form: tämänlajinen (from tämän, 'of this' and lajinen, 'kind') → tänlainen → tällainen, and further to tällä(i)nen for some non-standard speech.

New loan words may exhibit vowel disharmony; for example, olympialaiset ('Olympic games') and sekundäärinen ('secondary') have both front and back vowels. In standard Finnish, these words are pronounced as they are spelled, but many speakers apply vowel harmony – olumpialaiset, and sekundaarinen or sekyndäärinen.

Mechanics[edit]

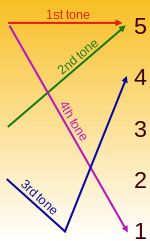

In seemingly all languages, pitch is used as a part of the system of intonation, which commonly encodes illocutionary force (to distinguish interrogative from declarative sentences, for instance) or contributes paralinguistic information.[4] Using pitch this way, however, does not qualify a language as tonal. Rather, tonal languages are those that use pitch contrastively to distinguish at least some morphemes.[5] Thus, in tone languages there exist minimal pairs (or sets thereof) whose members differ in terms of tone and meaning, but nothing else. For example, Mandarin Chinese contrasts the following five meanings solely on the basis of tone, since the segments /ma/ are common to all five; this qualifies Mandarin as a tone language.

- mā (媽/妈) 'mother'

- má (麻/麻) 'hemp'

- mǎ (馬/马) 'horse'

- mà (罵/骂) 'scold'

- ma (嗎/吗) (an interrogative particle)

Languages differ in what types of tones they make use of. Level tones are tones which maintain a relatively constant pitch during their articulation. Languages may have up to at least four (but possibly five) level tones.[4] Contour tones, by contrast, feature a change in pitch while being articulated. Typically, contour tones are only found in languages with a large number of level tones,[4] but there are some exceptions. For example, Amahuaca, which is a language with two contour tones (rising and falling) but no level tones.[6]

Tones do not occur on every segment. Rather, tones are found on particular kinds of phonological units termed tone-bearing units. In some languages, the syllable is the tone-bearing unit. In others, the tone-bearing unit is the mora, a unit[7]

Tone is most frequently manifested on vowels, but in most tonal languages where voiced syllabic consonants occur they will bear tone as well. This is especially common with syllabic nasals, for example in many Bantu and Kru languages, but also occurs in Serbo-Croatian. It is also possible for lexically contrastive pitch (or tone) to span entire words or morphemes instead of manifesting on the syllable nucleus (vowels), which is the case in Punjabi.[8]

Tones can interact in complex ways through a process known as tone sandhi.

Examples:

The following is minimal tone set from Mandarin Chinese, which has five tones, here transcribed by diacritics over the vowels:

- A high level tone: /á/ (pinyin ⟨ā⟩)

- A tone starting with mid pitch and rising to a high pitch: /ǎ/ (pinyin ⟨á⟩)

- A low tone with a slight fall (if there is no following syllable, it may start with a dip then rise to a high pitch): /à/ (pinyin ⟨ǎ⟩)

- A short, sharply falling tone, starting high and falling to the bottom of the speaker's vocal range: /â/ (pinyin ⟨à⟩)

- A neutral tone, with no specific contour, used on weak syllables; its pitch depends chiefly on the tone of the preceding syllable.

These tones combine with a syllable such as ma to produce different words. A minimal set based on ma are, in pinyin transcription,

- mā (媽/妈) 'mother'

- má (麻/麻) 'hemp'

- mǎ (馬/马) 'horse'

- mà (罵/骂) 'scold'

- ma (嗎/吗) (an interrogative particle)

These may be combined into the rather contrived sentence,

- 妈妈骂马的麻吗?/媽媽罵馬的麻嗎?

- Pinyin: Māma mà mǎde má ma?

- IPA /máma mâ màtə mǎ ma/

- Translation: 'Is mom scolding the horse's hemp?'

A well-known tongue-twister in Standard Thai is:

- ไหมใหม่ไหม้มั้ย.

- IPA: /mǎi mài mâi mái/

- Translation: 'Does new silk burn?'[9]

Vietnamese has its version:

- Bấy nay bây bày bảy bẫy bậy.

- IPA: [ɓʌ̌i̯ nai̯ ɓʌi̯ ɓʌ̂i̯ ɓa᷉i̯ ɓʌ̌ˀi̯ ɓʌ̂ˀi̯]

- Translation: 'All along you've set up the seven traps incorrectly!'

Cantonese has its version:

- 一人因一日引一刃一印而忍

- Jyutping: jat1 jan4 jan1 jat1 jat6 jan5 jat1 jan6 jat1 jan3 ji4 jan2

- IPA:

- Translation: A person why stay endured due to a day have introduced a knife and a print.

Orthography[edit]

While several different systems have been used to write Yupʼik, the most widely used orthography today is that adopted by the Alaska Native Language Center and exemplified in Jacobson's (1984) dictionary, Jacobson's (1995) learner's grammar, and Miyaoka's (2012) grammar. The orthography is a Latin-script alphabet; the letters and digraphs used in alphabetical order are listed below, along with an indication of their associated phonemes in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

| Letter / digraph | IPA | Letter / digraph | IPA | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | /a/ | p | /p/ | ||

| c | /tʃ/ | q | /q/ | ||

| e | /ə/ | r | /ʁ/ | represents /χ/ word-finally | |

| g | /ɣ/ | rr | /χ/ | ||

| gg | /x/ | s | /z/ | represents /s/ word-initially | |

| i | /i/ | ss | /s/ | ||

| k | /k/ | t | /t/ | ||

| l | /l/ | u | /r/ | ||

| ll | /ɬ/ | u͡g | /ɣʷ/ | ||

| m | /m/ | u͡r | /ʁʷ/ | ||

| ḿ | /m̥/ | u͡rr | [χʷ] | doesn't contrast with /ʁʷ/ | |

| n | /n/ | v | /v/ | ||

| ń | /n̥/ | vv | /f/ | ||

| ng | /ŋ/ | w | /xʷ/ | ||

| ńg | /ŋ̊/ | y | /j/ |

The vowel qualities /a, i, u/ may occur long; these are written aa, ii, uu when vowel length is not a result of stress.[10] Consonants may also occur long (geminate), but their occurrence is often predictable by regular phonological rules, and so in these cases is not marked in the orthography.[10] Where long consonants occur unpredictably they are indicated with an apostrophe following consonant. For example, Yupiaq and Yupʼik both contain a geminate p (/pː/). In Yupiaq length is predictable and hence is not marked; in Yupʼik the length is not predictable and so must be indicated with the apostrophe. An apostrophe is also used to separate n from g, to distinguish n'g /nɣ/ from the digraph ng /ŋ/. Apostrophes are also used between two consonants to indicate that voicing assimilation has not occurred (see below), and between two vowels to indicate the lack of gemination of a preceding consonant.[10] A hyphen is used to separate a clitic from its host.[11]

Phonology[edit]

Vowels[edit]

Yup'ik contrasts four vowel qualities: /a i u ə/. The reduced vowel /ə/ always manifests phonetically short in duration, but the other three vowel qualities may occur phonetically short or long: [a aː i iː u uː]. Phonetically long vowels come about when a full vowel (/a i u/) is lengthened by stress (see below), or when two single vowels are brought together across a morpheme boundary. The effect is that while phonetic vowel length may yield a surface contrast between words, phonetic length is predictable and thus not phonemically contrastive.[11]

| Front (unrounded) | Central

(unrounded) |

Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-low | i | ə | u |

| Low | a |

The vowel qualities [e o] are allophones of /i u/, and are found preceding uvular consonants (such as [q] or [ʁ]) and preceding the back vowel [a].[12]

Consonants[edit]

Yup'ik does not contrast voicing in stops, but has a wide range of fricatives that contrast in voicing. Contrasts between /s/ and /z/ and between /f/ and /v/ are rare, however, and the greater part of the voicing contrasts among fricatives is between the laterals /l/ and /ɬ/, the velars /x/ and /ɣ/, and the uvulars /χ/ and /ʁ/. For some speakers, there is also a voicing contrast among the nasal consonants, which is typologically somewhat rare. Any consonant may occur as a geminate word-medially, and consonant length is contrastive.[11]

| Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar

/ Palatal |

Velar | Uvular | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m̥ | m | n̥ | n | ŋ̊ | ŋ | |||||

| Stop | p | t | k | q | |||||||

| Affricate | [ts] | tʃ | |||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | s | z | x | ɣ | χ | ʁ | |||

| Labialized | xʷ | ɣʷ | [χʷ] | ʁʷ | |||||||

| Lateral | ɬ | ||||||||||

| Approximant | j | [w] | |||||||||

| l | |||||||||||

The voiceless labialized uvular fricative [χʷ] occurs only in some speech variants and doesn't contrast with its voiced counterpart /ʁʷ/. The voiceless alveolar affricate [ts] is an allophone of /tʃ/ before the schwa vowel. The voiced labiovelar approximant [w] is an allophone of /v/ found between two full vowels.

/l/ is not phonetically a fricative, but behaves as one phonologically (in particular with regard to voicing alternations, where it alternates with [ɬ]; see below).

Dialect variations[edit]

In Norton Sound, as well as some villages on the lower Yukon, /j/ tends to be pronounced as [z] when following a consonant, and geminate /jː/ as [zː]. For example, the word angyaq "boat" of General Central Yup'ik (GCY) is angsaq [aŋzaq] Norton Sound.[10][11]

Conversely, In the Hooper Bay-Chevak (HBC) dialect, there is no /z/ phoneme, and /j/ is used in its place, such that GCY qasgiq [qazɣeq] is pronounced qaygiq [qajɣeq]. HBC does not have the [w] allophone of /v/, such that /v/ is pronounced [v] in all contexts,[10] and there are no labialized uvular fricatives.[11]

In the Nunivak dialect, one finds /aː/ in place of GCY /ai/, such that GCY cukaitut "they are slow" is pronounced cukaatut, there is no word-final fortition of /x/ and /χ/ (see below), and word-initial /xʷ/ is pronounced [kʷ].[10]

Voicing alternations[edit]

There are a variety of voicing assimilation processes (specifically, devoicing) that apply mostly predictably to continuant consonants (fricatives and nasals); these processes are not represented in the orthography.[13]

- The voiced fricatives /v, z, l, ɣ, ʁ/ undergo voicing assimilation when adjacent to the voiceless stops /p, t, k, q/; this occurs progressively (left-to-right) and regressively (right-to-left). Thus ekvik is pronounced [əkfik], and qilugtuq /qiluɣ-tu-q/ is pronounced [qiluxtoq] (compare qilugaa /qiluɣ-a-a/ [qiluːɣaː]).

- Progressive voicing assimilation occurs from fricatives to fricatives: inarrvik /inaχ-vik/ is pronounced [inaχfik].

- Progressive voicing assimilation occurs from stops to nasals: ciut-ngu-uq "it is an ear" is pronounced [tʃiutŋ̊uːq].

- Progressive voicing optionally occurs from voiceless fricatives to nasals: errneq is pronounced [əχn̥əq] or [əχnəq].[11]

Occasionally these assimilation processes do not apply, and in the orthography an apostrophe is written in the middle of the consonant cluster to indicate this: at'nguq is pronounced [atŋoq], not [atŋ̊oq].[13]

Fricatives are devoiced word-initially and word-finally.[11]

Word-final fortition[edit]

Another common phonological alternation of Yup'ik is word-final fortition. Only the stops /t k q/, the nasals /m n ŋ/, and the fricative /χ/ may occur word-finally. Any other fricative (and in many cases also /χ/) will become a plosive when it occurs at the end of a word. For example, qayar-pak "big kayak" is pronounced [qajaχpak], while "kayak" alone is [qajaq]; the velar fricative becomes a stop word-finally. Moreover, the [k] of -pak is only a stop by virtue of it being word-final: if another suffix is added, as in qayar-pag-tun "like a big kayak" a fricative is found in place of that stop: [qajaχpaxtun].[11]

Elision[edit]

The voiced velar consonants /ɣ ŋ/ are elided between single vowels, if the first is a full vowel: /tuma-ŋi/ is pronounced tumai [tumːai] (with geminate [mː] resulting from automatic gemination; see below).[11]

Prosody[edit]

Yup'ik has an iambic stress system. Starting from the leftmost syllable in a word and moving rightward, syllables usually are grouped into units (termed feet) containing two syllables each, and the second syllable of each foot is stressed. (However, feet in Yup'ik may also consist of a single syllable, which is almost always closed and must bear stress.) For example, in the word pissuqatalliniluni "apparently about to hunt", every second syllable (save the last) is stressed. The most prominent of these (i.e., the syllable that has primary stress) is the rightmost of the stressed syllables.[11]

The iambic stress system of Yup'ik results in predicable iambic lengthening, a processes that serves to increase the weight of the prominent syllable in a foot.[14] When lengthening cannot apply, a variety of processes involving either elision or gemination apply to create a well-formed prosodic word.[10][11]

Iambic lengthening[edit]

Iambic lengthening is the process by which the second syllable in an iambic foot is made more prominent by lengthening the duration of the vowel in that syllable.[14] In Yup'ik, a bisyllabic foot whose syllables each contain one phonologically single vowel will be pronounced with a long vowel in the second syllable. Thus pissuqatalliniluni /pisuqataɬiniluni/ "apparently about to hunt" is pronounced [(pi.'suː)(qa.'taː)(ɬi.'niː)lu.ni]. Following standard linguistic convention, parentheses here demarcate feet, periods represent the remaining syllable boundaries, and apostrophes occur before syllables that bear stress. In this word the second, fourth, and sixth syllables are pronounced with long vowels as a result of iambic lengthening.[14][15][16] Iambic lengthening does not apply to final syllables in a word.[10][11]

Because the vowel /ə/ cannot occur long in Yup'ik, when a syllable whose nucleus is /ə/ is in line to receive stress, iambic lengthening cannot apply. Instead, one of two things may happen. In Norton Sound dialects, the consonant following /ə/ will geminate if that consonant is not part of a cluster. This also occurs outside of Norton Sound if the consonants before and after /ə/ are phonetically similar. For example, /tuməmi/ "on the footprint" is not pronounced *[(tu.'məː)mi], which would be expected by iambic lengthening, but rather is pronounced [(tu.'məm)mi], with gemination of the second /m/ to increase the weight of the second syllable.[14][15][16]

Regressive stress[edit]

There are a variety of prosodic factors that cause stress to retract (move backward) to a syllable where it wouldn't otherwise be expected, given the usual iambic stress pattern. (These processes do not apply, however, in the Norton Sound dialects.[11]) The processes by which stress retracts under prosodically-conditioned factors are said to feature regression of stress in Miyaoka's (2012) grammar. When regression occurs, the syllable to which stress regresses constitutes a monosyllabic foot.[11]

The first of these processes is related to the inability of /ə/ to occur long. Outside of Norton Sound, if the consonants before and after /ə/ are phonetically dissimilar, /ə/ will elide, and stress will retract to a syllable whose nucleus is the vowel before the elided /ə/. For example, /nəqə-ni/ "his own fish" is not pronounced *[(nə.'qəː)ni], which would be expected by iambic lengthening, but rather is pronounced neq'ni [('nəq)ni], which features the elision of /ə/ and a monosyllabic foot.[11]

Second, if the first syllable of a word is closed (ends in a consonant), this syllable constitutes a monosyllabic foot and receives stress. Iambic footing continues left-to-right from the right edge of that foot. For example, nerciqsugnarquq "(s)he probably will eat" is has the stress pattern [('nəχ)(tʃiq.'sux)naχ.qoq], with stress on the first and third syllables.[10][12][13]

Another third prosodic factor that influences regressive is hiatus: the occurrence of adjacent vowels. Yup'ik disallows hiatus at the boundaries between feet: any two consecutive vowels must be grouped within the same foot. If two vowels are adjacent, and the first of these would be at the right edge of a foot (and thus stressed) given the usual iambic footing, the stress retracts to a preceding syllable. Without regressive accent, Yupiaq /jupiaq/ would be pronounced *[(ju.'piː)aq], but because of the ban on hiatus at foot boundaries, stress retracts to the initial syllable, and consonant gemination occurs to increase the weight of that initial syllable, resulting in [('jup)pi.aq].[11] This process is termed automatic gemination in Jacobson's (1995) grammar.

Yup'ik also disallows iambic feet that consist of a closed syllable followed by an open one, i.e. feet of the form CVC.'CV(ː), where C and V stand for "consonant" and "vowel" respectively. To avoid this type of foot, stress retracts: cangatenrituten /tʃaŋatənʁitutən/ has the stress pattern [(tʃa.'ŋaː)('tən)(ʁi.'tuː)tən] to avoid the iambic foot *(tən.'ʁiː) that would otherwise be expected.[11]

Grammar[edit]

Yup'ik is has highly synthetic morphology: the number of morphemes within a word is very high. The language is moreover agglutinative, meaning that affixation is the primary strategy for word formation, and that an affixes, when added to a word, do not typically affect the forms of neighboring affixes. Because of the tendency to create very long verbs through suffixation, a Yupʼik word often carries as much information as an English sentence. Word order is often quite free.

Morphology[edit]

In descriptive work on Yup'ik, there are four regions within nouns and verbs that are commonly identified. The first of these is often called the stem (equivalent to the notion of a root), which carries the core meaning of the word. Following the stem come zero or more postbases,[17] which are derivational modifiers that change the category of the word or augment its meaning. (Yup'ik does not have adjectives; nominal roots and postbases are used instead.) The third section is called an ending, which carries the inflectional categories of case (on nouns), grammatical mood (on verbs), person, and number.[18] Finally, optional enclitics may be added, which usually indicate "the speaker's attitude towards what he is saying such as questioning, hoping, reporting, etc." [18] Orthographically, enclitics are separated from the rest of the word with a hyphen.[17][19] However, since hyphens are already used in glosses to separate morphemes, there is potential for confusion as to whether a morpheme is a suffix or an enclitic, so in glosses the equals sign is used instead.

| Stem | Postbases | Ending | Enclitic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yup'ik | angyar | -pa | -li | -yu | -kapigte | -llru | -u | -nga | |

| gloss | boat | AUG ("big") | make | DES ("want") | ITS ("very much") | PST | IND | 1SG | |

| translation | "I wished very much to build a big boat" | ||||||||

| Stem | Postbases | Ending | Enclitic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yup'ik | assir | -tu | -a | =gguq | |

| gloss | good | IND | 1SG | RPR (reportative) | |

| translations | "(he says) I'm fine" | ||||

| "(tell him) I'm fine" | |||||

| Stem | Postbases | Ending | Enclitic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yup'ik | kipus | -vik | -Ø | ||

| gloss | buy | LOC ("place for") | ABS.SG | ||

| translations | "store" (lit. "place for buying") | ||||

| Stem | Postbases | Ending | Enclitic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yup'ik | qayar | -pa | -li | -yara | -qa | |

| gloss | kayak | AUG ("big") | make | (nominalizer) | ABS.1SG.SG | |

| translations | "the way I make a big kayak" | |||||

Because post-bases are derivational morphemes, and thus can change the part of speech of a word, many verbs are built from noun stems, and vice versa. For example, neqe-ngqer-tua "I have fish" is a verb, despite the fact that neqe- "fish" is a noun; the postbase -ngqerr "have" makes the resulting word a verb. These changes in grammatical category can apply iteratively, such that over the course of word formation, a word may become a noun, then a verb, then back to a noun, and so on.[11][20]

Verb conjugation and agreement[edit]

The inflection of Yup'ik verbs involves obligatory marking of grammatical mood and agreement. There are four so-called independent moods, which occur on verbs in independent clauses: the indicative, optative, interrogative, and participial. Yupʼik also has ten connective moods, which occur on the verbs of adverbial clauses; the connective moods are the Yup'ik equivalent of many subordinating conjunctions of English, and are often translated as 'because', 'although', 'if' and 'while'.[21] The form of the various moods is affected by the transitivity of the verb. For example, the intransitive form of the participial mood suffix is usually -lriar, but when this mood is suffixed to a transitive verb, its form is -ke.[22]

| Forms | Common uses (not exhaustive) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent moods | Indicative | -gur (intransitive)

-gar (transitive) |

Used to form declarative sentences |

| Participial | -lriar, or -ngur after /t/ (intransitive)

-ke (transitive) |

Varied | |

| Interrogative | -ta (after a consonant, if subject is third person)

-ga (after a vowel, if subject is third person) -ci (if subject is first or second person) |

Used to form wh-questions | |

| Optative | -li (if subject is third person)

-la (if subject is first person) -gi or -na (if subject is second person) |

Used to express wishes, requests, suggestions, commands,

and occasionally to make declarative statements | |

| Co-subordinate | Appositional | -lu, or -na after certain suffixes | Used for cosubordination, coordination, and in independent clauses |

| Connective moods | Causal | -nga | Used to form subordinate clauses (translated "because, when") |

| Constative | -gaq(a) | Used to form subordinate clauses (translated "whenever") | |

| Precessive | -pailg | Used to form subordinate clauses (translated "before") | |

| Concessive | -ngrrarr | Used to form subordinate clauses (translated "although, even if") | |

| Conditional | -k(u) | Used to form subordinate clauses (translated "if") | |

| Indirective | -cu(a) | Used to express indirect suggestions, admonishment | |

| Contemporative | -llr | Used to form subordinate clauses (translated "when") | |

| Simultaneous | -nginanrr | Used to form subordinate clauses (translated "while") | |

| Stative | -Ø | Used to form subordinate clauses (translated "being in the state of") |

Quasi-connective moods

In addition to the connective moods listed above, there are five so-called "quasi-connective" moods. Though these are adverbial adjuncts to main clauses and thus are similar in function to the connective moods, they inflect like nominals (they inflect with case, not agreement).[11]

Agreement

Yup'ik has a rich system of agreement on verbs. Three numbers (singular, dual, and plural) are distinguished, as well as three persons (first, second, and third). The third person is unmarked when cross-referencing subjects,[11] and the verbs of dependent clauses may have two types of third person forms depending on whether some argument is co-refers with the subject of the verb in the independent clause (see "Cross-clausal coreference" below).[10][11] Intransitive verbs agree with their sole argument, and transitive verbs agree with both arguments. To the extent that subject and object agreement markers are not fusional, subject agreement linearly precedes object agreement. Depending on the grammatical mood of the verb and which grammatical persons are being cross-referenced, agreement may display either an ergative pattern (where the sole argument of an intransitive verb is cross-referenced with the same morpheme that it would be if it were the object of a transitive verb) or an accusative pattern (where the sole argument of an intransitive verb is cross-referenced with the same morpheme that it would be if it were the subject of a transitive verb).[11]

Agreement markers vary in form depending on the grammatical mood of the verb. The two examples below illustrate this. In (1), the 1SG>3SG agreement marker is -qa because the verb is in the indicative mood, while in (2) the agreement marker is -ku due to verb being in the optative mood.

| (1) | assik-a-qa | (2) | patu-la-ku=tuq | egaleq | |

| like-IND.TR-1SG>3SG | close-OPT-1SG>3SG=wish | window.ABS | |||

| "I like him/her/it" | "I hope I will close the window" | ||||

The participial and indicative share a set of agreement markers, and all the connective moods likewise share a common set (which is shared also with some possessed nouns).[11]

Cross-clausal co-reference[edit]

The form of 3rd-person agreement in dependent clauses may vary depending on whether that 3rd-person argument is the same referent as, or a different referent than, a 3rd-person subject of the independent clause. In some descriptive work on the language, when the subject of the independent clause is co-referential with the relevant argument in the dependent clause, the agreement in the dependent clause is said to reflect a "fourth"[10] or a "reflexive third"[11] person. Jacobson (1995) uses the following contrast to illustrate:

| (3) | Nere-llru-uq | ermig-pailg-an | (4) | Nere-llru-uq | ermig-paileg-mi | |

| eat-PST-IND.3SG | wash.face-before-3SG | eat-PST-IND.3SG | wash.face-before-4SG | |||

| "She ate before she (another) washed her face." | "She ate before she (herself) washed her face." | |||||

The intransitive agreement in the dependent clause ermig-pailg-an in (3) is -an, indicating that the argument of the dependent clause is a different referent than the subject of the independent clause nerellruuq, while in (4) the agreement -mi indicates that the arguments of each clause are co-referential. Some grammatical moods do not have associated agreement markers that contrast these two types of third person.[11]

Some researchers have argued that the contrast in (3-4) exemplifies a type of switch-reference,[23][24] though McKenzie (2015) claims Yup'ik does not have the true characteristics of switch-reference, and that the Yup'ik system is better understood in terms of obviation or long-distance anaphora.[25]

Nouns[edit]

Grammatical case[edit]

The morphosyntactic alignment of Yupʼik is ergative-absolutive,[11] meaning that subjects of intransitive verbs bear the same grammatical case (the absolutive) as the objects of transitive verbs, while the subjects of transitive verbs have a different case (the ergative). For example, the sentence Angyaq tak'uq ("The boat is long") features an intransitive verb, and the subject (angyaq, "the boat") is in the absolutive case. By comparison, in the sentence Angyaq kiputaa ("He buys the boat"), the verb is transitive, and it is now the object (angyaq, "the boat") that bears the absolutive.[26] This contrasts with nominative-accusative languages like English, where the subjects of intransitives and transitives are identical in form ("He slept", "He ate the bread"), while the objects of transitives have a different case ("The moose saw him").

In addition to the absolutive and ergative structural cases (the latter of which is syncretic with the genitive; collectively the ergative and genitive are usually called the relative case[10][11]), there are at least five other cases that are mostly-nonstructural: ablative-modalis (a historical syncretism of ablative and instrumental cases), allative, locative, perlative, and equalis.[11]

| Common function(s) | English equivalents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural | Absolutive | Identifies the sole argument of an intransitive verb

Identifies the definite object of a transitive verb |

(none) | |

| Relative | Ergative | Identifies the subject of a transitive verb | (none) | |

| Genitive | Identifies a possessor | 's (as in John's book) | ||

| Non-structural | Ablative-modalis | Identifies a spatial or temporal starting point

Marks nominals demoted from absolutive case under valency reduction |

from

(none) | |

| Allative | Identifies a spatial or temporal end point

Marks nominals demoted from relative case under valency reduction |

to

(none) | ||

| Locative | Identifies spatial or temporal locations

Indicates the standard of comparison in comparatives |

at, in, during

than | ||

| Perlative | Identifies a spatial or temporal route through which movement occurs | along, via, by way of | ||

| Equalis | Marks a nominal that is similar/equivalent to another; commonly

co-occurs with the verb ayuqe- "resemble" |

(none) | ||

The forms of these grammatical cases are variable, depending on the grammatical person and number of the head noun as well as the person and number of its possessor (if there is one).

Word order[edit]

Yup'ik has considerably more freedom of word order than English does. In English, the word order of subjects and objects with respect to a verb reflects the thematic roles of the subject and object. For example, the English sentence The dog bit the preacher means something different than The preacher bit the dog does; this is because in English, the noun that comes before the verb must be the agent (the biter), while the noun following the verb must be the theme (the individual or thing that is bitten).

In Yupʼik, word order is freer because the rich inflectional system serves to unambiguously identify thematic relations without recourse to word order. The Yup'ik sentences Qimugtem keggellrua agayulirta (dog.ERG bit preacher.ABS) and Agayulirta keggellrua qimugtem (preacher.ABS bit dog.ERG ) both mean "the dog bit the preacher", for instance: the word order varies between these sentences, but the fact that qimugtem ("dog") is marked with ergative case (-m) is sufficient to identify it as the thematic agent. Thus, to say "the preacher bit the dog" in Yup'ik, one would need change which noun gets ergative case and which gets absolutive: qimugta keggellrua agayulirtem (dog.ABS bit preacher.ERG). [27]

Spatial deixis[edit]

Yup'ik has a rich system of spatial deixis. That is, many of the spatial properties of things and events are linguistically encoded in great detail; this holds true for demonstrative pronouns (like English "this one", "that one") as well as spatial adverbs ("here", "there").

There are twelve categories that define the orientation of a thing or event with respect to the environment. The environment in this sense includes topographical features (e.g., there is a contrast between upriver and downriver), the participants in the speech event (e.g., there is a contrast between proximity to the speaker and proximity to the hearer), and the linguistic context (one of these twelve categories is used for anaphora). This twelve-way contrast is cross-cut by a trinomial contrast in horizontal extension/motion: this determines whether the referent is extended (horizontally long or moving) or non-extended, and if non-extended, whether distal (typically far away, indistinct, and invisible) or proximal (typically nearby, distinct, and visible).

To illustrate, the spatial demonstrative roots of Yup'ik (which are then inflected for case and number) are presented in the following table from Miyaoka (2012).

| Class | Translation of class | Extended | Non-extended | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distal | Proximal | |||

| I | here (near speaker) | mat- | u- | |

| II | there (near hearer) | tamat- | tau- | |

| III | aforementioned / known | im- | ||

| IV | approaching (in space or time) | uk- | ||

| V | over there | au͡g- | am- | ing- |

| VI | across there, on the opposite bank | ag- | akm- | ik- |

| VII | back/up there, away from river | pau͡g- | pam- | ping- |

| VIII | up/above there (vertically) | pag- | pakm- | pik- |

| IX | down/below there, toward river (bank) | un- | cam- | kan- |

| X | out there, toward exit, downriver | un'g- | cakm- | ug- |

| XI | inside, upriver, inland | qau͡g- | qam- | kiug-/kiu͡g- |

| XII | outside, north | qag- | qakm- | kex- |

- ^ van der Hulst & van de Weijer (1995:498)

- ^ van der Hulst & van de Weijer (1995:498–499)

- ^ Hellstrom (1976:86)

- ^ a b c Yip, Moira (2002-08-15). Tone. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77445-1.

- ^ Haspelmath, Martin; König, Ekkehard; Oesterreicher, Wulf; Raible, Wolfgang, eds. (2001-01-07), "Tone systems", Language Typology and Language Universals, Berlin • New York: Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-019426-5, retrieved 2021-01-04

- ^ Maddieson, Ian (1978). Universals of tone. In J.H. Greenberg (ed.), Universals of Human Language, Volume 2: Phonology. Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press. pp. 335–66.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Yip, Moira (2002-08-15). Tone. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77445-1.

- ^ Singh, Chander Shekhar (2004). Punjabi Prosody: The Old Tradition and The New Paradigm. Sri Lanka: Polgasowita: Sikuru Prakasakayo. pp. 70–82.

- ^ Tones change over time, but may retain their original spelling. The Thai spelling of the final word in the tongue-twister, ⟨ไหม⟩, indicates a rising tone, but the word is now commonly pronounced with a high tone. Therefore a new spelling, มั้ย, is occasionally seen in informal writing.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Jacobson, Steven A. ([2007], ©1995). A practical grammar of the central Alaskan Yup'ik Eskimo language. Alaska Native Language Center and Program, University of Alaska. ISBN 1-55500-050-9. OCLC 883251222.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Miyaoka, Osahito (2012-10-29). A Grammar of Central Alaskan Yupik (CAY). De Gruyter Mouton. doi:10.1515/9783110278576. ISBN 978-3-11-027857-6.

- ^ a b Miyaoka, Osahito (2012-10-29). A Grammar of Central Alaskan Yupik (CAY). De Gruyter Mouton. doi:10.1515/9783110278576. ISBN 978-3-11-027857-6.

- ^ a b c Jacobson, Steven A. ([2007], ©1995). A practical grammar of the central Alaskan Yup'ik Eskimo language. Alaska Native Language Center and Program, University of Alaska. ISBN 1-55500-050-9. OCLC 883251222.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Buckley, Eugene (1998). "Iambic Lengthening and Final Vowels". International Journal of American Linguistics. 64(3): 179–223.

- ^ a b Krauss, Michael. (1985). Yupic Eskimo prosodic systems : descriptive and comparative studies. ISBN 0-933769-37-7. OCLC 260177704.

- ^ a b Hayes, Bruce (1985). "Iambic and trochaic rhythm in stress rules". Proceedings of the Eleventh Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, ed. Mary Niepokuj et al.: 429–446.

- ^ a b Jacobson, Steven A. ([2007], ©1995). A practical grammar of the central Alaskan Yup'ik Eskimo language. Alaska Native Language Center and Program, University of Alaska. ISBN 1-55500-050-9. OCLC 883251222.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Reed et al. 1977, p. 18

- ^ a b c Miyaoka, Osahito (2012-10-29). A Grammar of Central Alaskan Yupik (CAY). De Gruyter Mouton. doi:10.1515/9783110278576. ISBN 978-3-11-027857-6.

- ^ Woodbury, Anthony (1981-01-01). Study of the Chevak Dialect of Central Yup'ik Eskimo. eScholarship, University of California. OCLC 1078287179.

- ^ Mithun, Marianne (2006). The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 234–235. ISBN 978-0-521-29875-9.

- ^ Miyaoka, Osahito (2012-10-29). A Grammar of Central Alaskan Yupik (CAY). De Gruyter Mouton. doi:10.1515/9783110278576. ISBN 978-3-11-027857-6.

- ^ Stirling, Lesley (1993-03-11). Switch-Reference and Discourse Representation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521402293.

- ^ Woodbury, Anthony C. (1983), "Switch-reference, syntactic organization, and rhetorical structure in Central Yup'ik Eskimo", Typological Studies in Language, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, p. 291, ISBN 978-90-272-2866-6, retrieved 2020-09-13

- ^ McKenzie, Andrew. A survey of switch-reference in North America. OCLC 915142700.

- ^ Reed et al. 1977, p. 64

- ^ "Central Yupʼik and the Schools". www.alaskool.org. Retrieved 2015-06-04.