User:Imperium2543546467/sandbox

| Mexican–American War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 73,532 regulars and volunteers[1] |

70,000 regulars[1] 12,000 irregulars[1] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

1,733 killed in battle (1,721 soldiers, 11 Marines, and 1 sailor)[1] 4,152 wounded[2] | 10,000 regulars dead (5,000 killed in battle)[1] | ||||||||

| Including civilians killed by the war's violence and military disease and accidental deaths, the Mexican death toll may have reached 25,000.[1] | |||||||||

| History of Mexico |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Mexican–American War[3],Cite error: There are <ref> tags on this page without content in them (see the help page). also known in Mexico as the War of Northern Aggression,[a] was an conflict between the United States of America and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed America's acceptance of Texas's statehood. The Mexican dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna still considered Texas to be a northeastern province and never recognized the Republic of Texas[4], which had declared independence (with United States intervention) and defeated Mexico a decade earlier. The US considered the border of Texas to be the Rio Grande river, while Mexico claimed that Nueces river was the border. In 1845, expansionist President James K. Polk sent troops to the disputed area, and built a fort at the Mexican side of the disputed territory in an attempt to gain Casus Belli[5]. After Mexican forces ambushed American forces, Polk sent a request to Congress that the US declare war. Congress approved the proposal and the United States declared war.

U.S. forces quickly took over Santa Fe de Nuevo México and the province of Alta California, and then moved south. Meanwhile, the U.S Navy blockaded the Pacific coast farther south in the Baja California Territory. The U.S. Army captured Mexico City, having marched west from the Veracruz, where the US staged their first ever amphibious landing.

The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, forced onto the remains of Mexico, ended the war and enforced the Mexican Cession of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México to the United States. The U.S. paid $15 million for the damage of the war and assumed $3.25 million of debt already owed earlier by Mexico to U.S. citizens. Mexico acknowledged the State of Texas and accepted the Rio Grande as its northern border with the U.S.

The expansion Polk envisioned[6] inspired great popularity in the United States, but the war drew criticism in the U.S. their casualties, cost, and unjustness,[7][8] particularly later on. The question of whether the new states would be slave states or not intensified the debate over slavery. Mexico's worsened domestic turmoil led to a "state of degradation and ruin".[9]

Origins of the war[edit]

In 1845, newly elected U.S. President James K. Polk made a offer to purchase Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México from Mexico, and to agree upon the Rio Grande river as the southern border of United States. When that offer was rejected, President Polk moved U.S. troops into the disputed Nueces Strip.

The Nueces Strip[edit]

The border of Texas as an independent state was never settled. The Republic of Texas claimed land up to the Rio Grande but Mexico refusedaccept these as valid, claiming that the Rio Grande in the treaty was the Nueces, and referred to the Rio Grande as the Rio Bravo.

Polk's gambit[edit]

In July 1845, Polk sent General Zachary Taylor to Texas, and by October 3,500 Americans were on the Nueces River, ready to take by force the disputed land. Polk wanted to protect the border and also coveted for the U.S. the continent clear to the Pacific Ocean.

In November 1845, Polk sent John Slidell, a secret representative, to Mexico City with an offer to the Mexican government of $25 million for the Rio Grande border in Texas and Mexico's provinces of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México.

Mexico's response[edit]

Mexican public opinion and all political factions agreed that selling the territories to the United States would tarnish the national honor.[10] Mexicans who opposed direct conflict with the United States, including President José Joaquín de Herrera, were viewed as traitors.[11] Opponents of de Herrera, considered Slidell's presence in Mexico City an insult. When de Herrera considered receiving Slidell to settle the problem of Texas annexation peacefully, he was accused of treason and deposed. After a more nationalistic government under Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga came to power, it publicly reaffirmed Mexico's claim to Texas[11] .

Outbreak of the war[edit]

In 1846, after Polk ordered General Taylor's troops into the disputed territory, Mexican forces attacked an American Army outpost ("Thornton Affair") in the occupied territory, killing 12 U.S. soldiers and capturing 52. These same Mexican troops later laid siege to an American fort along the Rio Grande.[12] Polk cited this attack as an invasion of U.S. territory and requested that the Congress declare war.

Nueces Strip[edit]

President Polk ordered General Taylor and his forces south to the Rio Grande, entering the territory that Mexicans disputed. The U.S. claimed that the border was the Rio Grande. However, Mexico refused to negotiate, claiming all of Texas.[13] Taylor ignored Mexican demands to withdraw to the Nueces. He constructed Fort Texas on the banks of the Rio Grande opposite the city of Matamoros[14].

The Mexican forces under General Santa Anna immediately prepared for war. On April 25, 1846, a 2,000-man Mexican cavalry detachment ambushed a 70-man U.S. patrol, which had been sent into the contested territory. In the Thornton Affair, the Mexican cavalry killed 11 American soldiers.[15]

Regarding the beginning of the war, Ulysses S. Grant, who had opposed the war but served as an army lieutenant in Taylor's Army, claims in his Personal Memoirs (1885) that the main goal of the U.S. Army's advance was to provoke the outbreak of war without attacking first, to prevent any opposition to the war.

Battle of Palo Alto[edit]

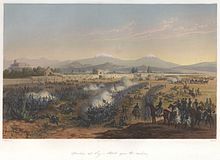

On May 8, Zachary Taylor and 2,400 troops arrived to relieve the fort.[16] However, the Mexican Army rushed north and intercepted him with at Palo Alto. The U.S. Army employed "flying artillery", a type of mobile light artillery that was mounted on horse carriages with the entire crew riding horses into battle. It provided support anywhere on the battlefield at a moments notice. It had a devastating effect on the Mexican army and was a decisive factor in the US victory.

Declarations of war[edit]

Mexico issued a proclamation, declaring Mexico's intent to fight a "defensive war" against the United States. Polk received word of the Thornton Affair, which, added to the Mexican government's rejection of Slidell, Polk believed, constituted a casus belli (cause for war).[17] His message to Congress, claimed that "Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon American soil."

The U.S. Congress approved the declaration of war with southern Democrats in strong support. on the final passage only 14 Whigs voted no,[18] including Rep. John Quincy Adams.

Mexico officially declared war by Congress on July 7, 1846.

Antonio López de Santa Anna[edit]

After the U.S. declared war on Mexico in 1846, Antonio López de Santa Anna wrote a letter to Mexico City stating he did not care to return to the presidency but would like to come out of exile in Cuba to use his military experience. President Valentín Gómez Farías, accepted the offer and allowed Santa Anna to return. Unbeknownst to President Farías, dealing with U.S. representatives to sell all contested territory to the U.S.on the condition that he be allowed back in Mexico through the U.S. naval blockades. Santa Anna returned to Mexico taking his place at the head of the army. He went back on his word, declaring himself president. As president, Santa Anna made an attempt to fight off the U.S. invasion.

Conduct of the war[edit]

After the declaration of war on May 13, 1846, U.S. forces invaded Mexican territory on fronts. The U.S. War Department sent a U.S. Cavalry force to invade western Mexico, reinforced by a Pacific fleet. This was done due to concerns that Britain might try to seize the area. Two more forces, were ordered to occupy Mexico as far south as the city of Monterrey.

New Mexico campaign[edit]

United States Army General Stephen W. Kearny moved southwest from Fort Leavenworth with about 1,700 men in his army to occupy Nuevo México and Alta California.[19]

In Santa Fe, Governor Manuel Armijo wanted to avoid battle but was forced to muster a defense. Armijo set up a position in Apache Canyon, a narrow pass about 10 miles (16 km) southeast of the city.[20] However, on August 14, before the American army was even in view, he decided not to fight.The New Mexican army retreated to Santa Fe.

Kearny and his troops encountered no Mexican forces when they arrived on August 15. Kearny and his force entered Santa Fe and claimed the New Mexico Territory for the United States without a shot being fired. Kearny declared himself the military governor and established a civilian government.

Kearny then took the remainder of his army west to Alta California,[19] leaving Colonel Sterling Price in command of U.S. forces in New Mexico.

Northeastern Mexico[edit]

The Mexican Army's defeats at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma caused political turmoil in Mexico, turmoil which Antonio López de Santa Anna used to revive his political career and return from exile in Cuba.[21]

Santa Anna promised the U.S. that if he was allowed to pass through the blockade, he would negotiate a peaceful conclusion to the war and sell the New Mexico and Alta California territories to the U.S.[22] Once Santa Anna arrived in Mexico City, offered his services to the Mexican government. Then, after being appointed commanding general, he reneged again and seized the presidency.

Led by Zachary Taylor, 2,300 U.S. troops crossed the Rio Grande, occuping the city of Matamoros, then Camargo and then proceeded south and besieged the city of Monterrey. The Battle of Monterrey resulted in serious losses on both sides. The American flying artillery was ineffective against the city fortifications. The Mexican forces were under General Pedro de Ampudia and repulsed Taylor's best infantry division at Fort Teneria.[23]

American soldiers had never engaged in urban warfare before and they marched straight down the open streets, where they were annihilated by Mexican defenders well-hidden in Monterrey's thick adobe homes.[23] Two days later, they changed their tactics. Texan soldiers advised Taylor's generals that the Americans needed to they needed to punch holes in the side or roofs of the homes and fight hand to hand inside the structures. This method proved successful.[24] Eventually, Ampudia's men were trapped in the city's central plaza, where shelling forced Ampudia to negotiate. Taylor agreed to allow the Mexican Army to evacuate and to an eight-week armistice in return for the surrender of the city. Taylor broke the armistice and occupied the city of Saltillo. Santa Anna blamed the loss of Monterrey and Saltillo on Ampudia and demoted him.

On February 22, 1847, Santa Anna personally marched north to fight Taylor with 20,000 men. Taylor, with 4,600 men, had entrenched at a mountain pass . Santa Anna suffered desertions on the way north and arrived with 15,000 men in a tired state. He demanded the surrender of the U.S. Army; when they refused he attacked the next morning. Santa Anna flanked the U.S. positions by sending his cavalry up the steep terrain that made up one side of the pass, while a division of infantry attacked frontally along the road leading to Buena Vista. Fighting ensued, during which the U.S. troops were nearly routed, but managed to cling to their entrenched position, thanks to a volunteer regiment led by Jefferson Davis, who formed them into a defensive V formation.[25] The Amerricams had considerable losses but Santa Anna had gotten word of a disruption in Mexico City, so he withdrew, leaving Taylor in control of part of Northern Mexico.

Northwestern Mexico[edit]

In 1847, Alexander W. Doniphan occupied Chihuahua City. Then in late April, Taylor ordered the First Missouri Mounted Volunteers to leave Chihuahua and join him at Saltillo. The civilian population of northern Mexico offered little resistance to the American invasion, possibly because the country had already been devastated by Comanche and Apache Indian raids

Southern Mexico[edit]

The U.S. Navy controlled the coast, clearing the way for U.S. troops and supplies. Even before hostilities began in the Nueces Strip, the U.S. Navy created a blockade. Since the Mexican Navy was almost non-existent, the U.S. Navy could operate unimpeded in Gulf waters.

Landings and siege of Veracruz[edit]

Rather than reinforce Taylor's army, President Polk sent a second army transported to the port of Veracruz by sea, to begin an invasion of the Mexican heartland. On March 9, 1847, Scott performed the first major amphibious landing in U.S. history in preparation for the Siege of Veracruz. A group of 12,000 soldiers successfully offloaded supplies, weapons, and horses near the walled city using specially designed landing crafts.

The city was defended by Mexican General Juan Morales with 3,400 men. Mortars and naval guns under Commodore Matthew C. Perry were used to reduce the city walls. After a bombardmen, the walls of Veracruz had a thirty-foot gap.[26] The effect of the extended barrage destroyed the will of the Mexican side to fight against a numerically superior force, and they surrendered the city after 12 days under siege. U.S. troops suffered 80 casualties, while the Mexican side had around 180 killed and wounded, about half of whom were civilian. During the siege, the U.S. side began to fall victim to yellow fever.

Advance on Puebla[edit]

Scott then marched westward on April 2, 1847, toward Mexico City with 8,500 troops, while Santa Anna set up a defensive position in a canyon with 12,000 troops, and artillery that were trained on the road, where he expected Scott to appear. However, Scott had sent 2,600 mounted dragoons ahead and they reached the pass on April 12. The Mexican artillery prematurely fired on them and therefore revealed their positions, beginning the Battle of Cerro Gordo.

Instead of taking the main road, Scott's troops trekked through the rough terrain to the north, setting up his artillery on the high ground and quietly flanking the Mexicans. Although by then aware of the positions of U.S. troops, Santa Anna and his troops were unprepared for the onslaught that followed. In the battle, the Mexican army was routed. The U.S. Army suffered 400 casualties, while the Mexicans suffered over 1,000 casualties and 3,000 were taken prisoner. In August 1847.

Pause at Puebla[edit]

In May, Scott pushed on to Puebla, the second largest city in Mexico. The city capitulated without resistance on May 1. During the following months, Scott gathered supplies and reinforcements at Puebla. Scott also made strong efforts to keep his troops disciplined and treat the Mexican people under occupation justly, so as to prevent a popular rising against his army.

Advance on Mexico City and its capture[edit]

With guerrillas harassing his line of communications back to Veracruz, Scott decided not to weaken his army to defend Puebla but, leaving only a garrison at Puebla to protect the sick and injured recovering there, advanced on Mexico City on August 7 with his remaining force. The capital was laid open in a series of battles around the right flank of the city defenses, the Battle of Contreras and Battle of Churubusco. With the subsequent battles of Molino del Rey and of Chapultepec, and the storming of the city gates, the capital was occupied. Scott became military governor of occupied Mexico City. His victories in this campaign made him an American national hero.

Santa Anna's last campaign[edit]

In late September 1847, Santa Anna made one last attempt to defeat the Americans, by cutting them off from the coast. General Joaquín Rea began the Siege of Puebla, soon joined by Santa Anna, but they failed to take it before the approach of a relief column from Veracruz under Brig. Gen. Joseph Lane prompted Santa Anna to stop him. Puebla was relieved by Gen. Lane October 12, 1847, following his defeat of Santa Anna at the Battle of Huamantla on October 9, 1847. Following the defeat, the new Mexican government led by Manuel de la Peña y Peña asked Santa Anna to turn over command of the army to General José Joaquín de Herrera.

Results[edit]

The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war and enforced the Mexican Cession of the northern territories of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México to the United States. Mexico acknowledged the loss of what became the State of Texas and accepted the Rio Grande as its northern border with the U.S. The losses amounted to one-third of its original territory from its 1821 independence.Though the annexed territory was about the size of Western Europe, it was sparsely populated.

Mexicans and Indians in the annexed territories faced a loss of rights, even though the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo promised American citizenship to all Mexican citizens living in the territory of the Mexican Cession.

Impact of the war in Mexico[edit]

The military defeat and loss of territory was a disastrous blow to Mexico .In the aftermath of the war, a group of prominent Mexicans compiled an assessment of the reasons for the war and Mexico's defeat, edited by Ramón Alcaraz and including contributions by Ignacio Ramírez, Guillermo Prieto, José María Iglesias, and Francisco Urquidi. They wrote that for "the true origin of the war, it is sufficient to say that the insatiable ambition of the United States, favored by our weakness, caused it."[9]

See also[edit]

- Battles of the Mexican–American War

- Christopher Werner, maker of the "Iron Palmetto" commemorating the loss of South Carolinians in the War

- Mexican–American Border War

- Reconquista (Mexico)

- Republic of Texas–United States relations

- Texas annexation

- Territories of Mexico

General:

- History of Mexico

- History of New Mexico

- History of the United States

- List of conflicts in the United States

- List of wars involving the United States

- List of wars involving Mexico

- Mexico–United States relations

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f Clodfelter 2017, p. 249.

- ^ Official DOD data Archived February 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Mexican–American War", Wikipedia, 2018-12-13, retrieved 2018-12-20

- ^ "Mexican-American War | Definition, Timeline, Causes, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- ^ "Mexican-American War | Definition, Timeline, Causes, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- ^ Rives 1913, p. 658.

- ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ Zinn, Howard (2003). "Chapter 8: We take nothing by conquest, Thank God". A People's History of the United States. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. p. 169.

- ^ a b Alcaraz, et al. The Other Side, pp. 1-2.

- ^ Miguel E. Soto, "The Monarchist Conspiracy and the Mexican War" in Essays on the Mexican War ed by Wayne Cutler; Texas A&M University Press. 1986. pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b Brooks (1849) pp. 61–62.

- ^ History.com

- ^ David Montejano (1987). Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986. University of Texas Press. p. 30. ISBN 9780292788077.

- ^ Justin Harvey Smith (1919). The war with Mexico vol. 1. Macmillan. p. 464.

- ^ K. Jack Bauer (1993). Zachary Taylor: Soldier, Planter, Statesman of the Old Southwest. Louisiana State University Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780807118511.

- ^ Brooks (1849) p. 121.

- ^ Smith (1919) p. 279.

- ^ Bauer (1992) p. 68.

- ^ a b "The Battle of Santa Fe". Early American Wars: A Guide to Early American Units and Battles before 1865. MyCivilWar.com. 2005–2008. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- ^ "New Mexico Historic Markers: Canoncito at Apache Canyon". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-04-15. Includes a link to a map.

- ^ Bauer (1992) p. 201.

- ^ Rives 1913, p. 233.

- ^ a b "Urban Warfare". Battle of Monterrey.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ Dishman, Christopher (2010). A Perfect Gibraltar: The Battle for Monterrey, Mexico. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-4140-4.

- ^ Shelby Foote, The Civil War: A Narrative: Volume 1: Fort Sumter to Perryville (1958)

- ^ Morgan, Robert, Lions of the West, Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2011 p. 282

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).