User:HopDot/sandbox

Feminine Ideals in Asian women

Korea[edit]

Asia is considered to have strict beauty standards, such as fair skin, full lips, strong eyebrows, defined cheekbones, poreless skin, and shiny hair. More particularly, South Korea is known for its unrealistic beauty standards, transforming the skincare industry. They seek a doll-like look, defined by a "very pale skin, big eyes with double eyelids, a tiny nose with a high nose bridge, and rosebud lips", a small face and subtly pointed chin. As these standards are difficult to achieve, cosmetic surgery became very popular. South Korea has the highest rate of cosmetic surgery per capita, and it keeps rising.

Between 1990 to 2006, the number of surgeries specializing in plastic surgery grew to the total rate of 8.9 percent per year, where the majority fraction undergoing these procedures are young people. A survey in 2004 showed that out of 1,565 female students attending college, 25.4 percent of them received plastic surgery for double eyelids, 3.6 percent for nose, and 1 percent for jaw/cheekbone[1]. Compared with the average 1 in 20 woman receiving plastic surgery in America, the average Korean woman that had surgery are approximately 1 in 5[2][3]. Due to the rise of Korean pop music culture, beauty aesthetic has undergo drastic changes where women relates beauty with professional success. In workplaces, women are expected to have physical attractiveness. Headshots are required with their resume in some places, and would often scrutinize the looks of applicants. The idealizations for a Korean woman is not only to require the a certain amount of professional skill, but also to be beautiful physically as well[2][3].

China[edit]

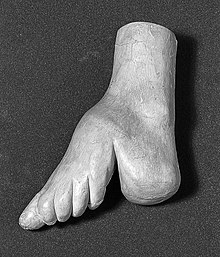

In China, both men and women pay more attention to the aesthetic feeling brought by women's appearance. Similar with South Korea, pale skin is desired as it correlates with a sheltered and work free lifestyle. A classic folk saying originated from Zhang Dai implies that “一白遮百丑”, literally translating to: Pale skin covers hundred flaws. Historically, Tang Dynasty women with a plump figure were considered the standardized view of beauty, contrasting with the expectations of tall, slim figures of today.[4] Starting from Song elitists and eventually popularized and ended in Qing Dynasty, foot binding was seen as an idolized representation of women’s petite beauty, referring to the practice as “三寸金莲”, literally translating to: three inch golden lotus.

“Beauty” is often used as a popular subject in Chinese literature and poetry. Historically “beauty” doesn’t necessarily relate solely to the appearance of a figure, and the criteria of beauty is clarified other than “beautiful looks”. Example of this would be relating “noble” with beautiful and “poor/peasant” with ugly. Famous Chinese beauties portrayed in historical literature almost always comes from a noble or middle class status. Depictions often times portray them as court ladies or servants of court ladies, garbed with glamorous feminine clothing to represent their identity. Women that doesn’t fit the social status of these dresses, such as commoners, were eliminated in terms of beauty depictions.[4]

Japan[edit]

Though sharing the same confucian culture with China, beauty standards were different between the two cultures historically. Dating back to the Heian Period, Japanese court ladies would color the teeth black of young women that is reaching adulthood. This custom existed in nobles, samurai clans and a large number of temples, but not in other groups such as commoners[4], known as “じゅうさんかねつけ” (Thirteen Iron Paste) and lasting until the Meiji Restoration (1868). Hairdressing and apparel were of supreme importance in the Fujiwara period; eyebrows were plucked and replaced with darker, wider ones painted higher on the forehead. Hair had to be at least long enough to touch the ground when seated, and faces were made up pale as to heighten the color of their dresses, in which they would pick the color and pattern based on seasons[5].

Scholar and art critic Okakura Kakuzo delivered in his compilations of lectures in 1905, that the considerable bases of beauty for modern Japan is, quote: "...to make a beautiful women, She is to possess a body not much exceeding five feet in height, with comparatively fair skin and proportionally well-developed limbs; a head covered with long, thick, and jet-black hair; an oval face with a straight nose, high and narrow; rather large eyes, with large deep-brown pupils and thick eyelashes, a small mouth, hiding behind its red, but not thin lips, even rows of small white teeth; ears not altogether small; and long thick eyebrows forming two horizontal but slightly curved lines, with a space left between them and the eyes...a very high as well as a very low forehead being considered not attractive."[6]

Source List[edit]

| This is a user sandbox of HopDot. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

- ^ a b Lee, Soohyung; Ryu, Keunkwan (2012). "Plastic Surgery: Investment in Human Capital or Consumption?". Journal of Human Capital. 6 (3): 224–250. doi:10.1086/667940. ISSN 1932-8575.

- ^ a b c Sharon Heijin Lee (2016). "Beauty Between Empires: Global Feminism, Plastic Surgery, and the Trouble with Self-Esteem". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 37 (1): 1. doi:10.5250/fronjwomestud.37.1.0001. ISSN 0160-9009.

- ^ a b c Stone, Zara (2013-05-24). "The K-Pop Plastic Surgery Obsession". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ a b c d Kyo, Cho; Selden, Kyoko (2015). "Selections from The Search for the Beautiful Woman: A Cultural History of Japanese and Chinese Beauty". Review of Japanese Culture and Society. 27 (1): 184–190. doi:10.1353/roj.2015.0022. ISSN 2329-9770.

- ^ a b Auriti, Giacinto (1952). "Aestheticism in Ancient Japan". East and West. 3: 13–19 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b Elise, Mizuta Lippit, Miya (2012-04-20). 美人 / Bijin / Beauty. eScholarship, University of California. OCLC 1021971608.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)