User:Hannahgrotz/sandbox

This is my sandbox

Classification[edit]

Patients with hypergraphia exhibit a wide variety of writing styles and content. While some write in a coherent, logical manner, others write in a more jumbled style (sometimes in a specific pattern).

Writing Style[edit]

Nonsensical Babble (psychosis):

Writing Content[edit]

In addition to writing in different forms (poetry, books, repeating one word, etc.), hypergraphia patients also differ in the complexity of their writings. While some writers (see Alice Flaherty) use their hypergraphia to help them write extensive papers and books, most patients do not write things with substance. Patients hospitalized with temporal lobe epilepsy and other disorders causing hypergraphia have written memos, and lists of random categories (like their favorite songs) and recorded their dreams in extreme length and detail.[1][2] Some patients that also suffer from temporal lobe epilepsy record the times and locations of each seizure compiled into a giant list.[2]

There are many accounts of patients writing in nonsensical patterns including writing in a center-seeking spiral starting around the edges of a piece of paper.[3] In one case study (Waxman and Geschwind, 2005), a patient even wrote backwards, so that the writing could only be interpreted with the aid of a mirror.[2] Sometimes the writing can consist of scribbles and frantic, random thoughts that are quickly jotted down on paper very frequently. Grammar can be present, but the meaning of these thoughts is generally hard to grasp and the sentences are loose.[3] In some cases, patients write extremely detailed accounts of events that are occurring at that time, or descriptions of the location they are in. [3]

Religious or moral undertones: Need more info here

Religious experiences and hypergraphia commonly occur with the presence of epileptic seizures. [4]

Causes[edit]

Certain drugs have been known to induce hypergraphia including donepezil. In one case study (Wicklund and Wright, 2012), a patient taking donepezil reported an elevation in mood and energy levels which led to hypergraphia and other excessive forms of speech (such as singing).[5] Six other cases of patients taking donepezil and experiencing mania have been previously reported. These patients also had cases of dementia, cognitive impairment from a cerebral aneurysm, bipolar I disorder, and/or depression. Researchers are unsure of why donepezil can induce mania and hypergraphia. It could potentially result from an increase in acetylcholine levels, which would also have an effect on the other neurotransmitters in the brain.[5]

Another potential cause of hypergraphia is from one of the body's neurotransmitters, dopamine (DA). Dopamine has been known to decrease latent inhibition, which causes a decreases in the ability to habituate to different stimuli. Low latent inhibition leads to an excessive level of stimulation and could contribute to the onset of hypergraphia and general creativity. This research implies that there is a direct correlation between the levels of DA between neuronal synapses and the level of creativity exhibited by the patient. DA agonists increase the levels of DA between synapses which results in higher levels of creativity, and the opposite is true for DA antagonists.[1]

Pathophysiology[edit]

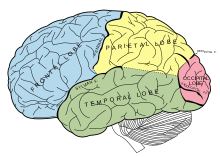

Right hemisphere (stroke, tumor, smaller right hippocampus):

Although hypergraphia cannot be isolated to one specific part of the brain, some areas are known to have more of an effect than others. The hippocampus has been found to play a role in the occurrence of temporal lobe epilepsy and schizophrenia. In one study (Cifelli and Grace, 2011), rats induced to have temporal lobe epilepsy showed an increase in dopamine neural activity in the hippocampus. Because hypergraphia has been linked to temporal lobe epilepsy and schizophrenia, the hippocampus could have an effect on hypergraphia as well.[6] In a different study (van Elst and Krishnamoorthy et al., 2003), patients with bilateral hippocampal atrophy (BHA) showed signs of having Geschwind syndrome, including hypergraphia.[7]

While epilepsy-induced hypergraphia is usually lateralized to the left cerebral hemisphere in the language areas, hypergraphia associated to lesions and other brain damage usually occurs in the right cerebral hemisphere.[8] Lesions to the right side of the brain usually cause hypergraphia because they can disinhibit language function on the left side of the brain.[1] Hypergraphia has also been known to be caused by right hemisphere strokes and tumors.[3][9]

Lesions to Wernicke's area on the left side of the brain can increase speech output, which can sometimes manifest itself in writing.[1]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Flaherty, Alice W. (December 2005). "Frontotemporal and dopaminergic control of idea generation and creative drive". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 493 (1): 147–153. doi:10.1002/cne.20768. PMC 2571074. PMID 16254989.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c Waxman, Stephen G.; Geschwind, Norman (2005). "Hypergraphia in temporal lobe epilepsy". Epilepsy & Behavior. 6 (2): 282–291. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.11.022. PMID 15710320.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c d Yamadori, Atsushi (January 1986). "Hypergraphia: a right hemisphere syndrome". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 49 (10): 1160–1164. doi:10.1136/jnnp.49.10.1160. PMC 1029050. PMID 3783177.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Wuerfel, J (April 2004). "Religiosity is associated with hippocampal but not amygdala volumes in patients with refractory epilepsy". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 75 (4): 640–642. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.06973. PMC 1739034. PMID 15026516.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Wicklund, Sarah (2012). "Donepezil-Induced Mania". Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 24 (3): 27. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11070160. PMID 23037669.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cifelli, Pierangelo; Grace, Anthony A. (12 July 2011). "Pilocarpine-induced temporal lobe epilepsy in the rat is associated with increased dopamine neuron activity". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (7): 957–964. doi:10.1017/S1461145711001106. PMC 3694768. PMID 21745437.

- ^ Van Elst, L. T.; Krishnamoorthy, E. S.; Bäumer, D.; Selai, C.; von Gunten, A.; Gene-Cos, N.; Ebert, D.; Trimble, M. R. (2003). "Psychopathological profile in patients with severe bilateral hippocampal atrophy and temporal lobe epilepsy: evidence in support of the Geschwind syndrome?". Epilepsy & Behavior : E&B. 4 (3): 291–7. doi:10.1016/s1525-5050(03)00084-2. PMID 12791331. S2CID 34974937.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Ishikawa, T.; Saito, M.; Fujimoto, S.; Imahashi, H. (2000). "Ictal increased writing preceded by dysphasic seizures". Brain & Development. 22 (6): 398–402. doi:10.1016/s0387-7604(00)00163-7. PMID 11042425. S2CID 43906342.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Imamura, T.; Yamadori, A.; Tsuburaya, K. (1992). "Hypergraphia associated with a brain tumour of the right cerebral hemisphere". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 55 (1): 25–7. doi:10.1136/jnnp.55.1.25. PMC 488927. PMID 1548492.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link)