User:Future Perfect at Sunrise/Historical portraits

This is an essay. It contains the advice or opinions of one or more Wikipedia contributors. This page is not an encyclopedia article, nor is it one of Wikipedia's policies or guidelines, as it has not been thoroughly vetted by the community. Some essays represent widespread norms; others only represent minority viewpoints. |

| This page in a nutshell: Before you insert an imaginary depiction of an historical personality in a biography article, think twice whether it really has encyclopedic value. |

Portraits of historical personalities are an important part of many history and biography articles. Unfortunately, for the large majority of people who lived before the age of photography, authentic portraits are unavailable and always will be. Most historical civilizations until quite recently simply didn't do portraits.

In this situation, editors often resort to non-contemporary, imaginary depictions instead. This essay argues that while such illustrations may sometimes serve a legitimate purpose, their use is more often unencyclopedic, useless and even harmful. Below you will find some suggestions about when to include or not to include such depictions.

In a few cases, imaginary portraiture has been contentious in Wikipedia for special cultural and ideological reasons other than those discussed here, most notoriously in the case of depictions of Mohammed. These special cases are outside the scope of this essay, although some of its arguments might also be applicable to them.

What this essay is also not about is the question of when to use non-free material of modern (mostly 20th century) personalities or persons who are still alive. For this, see the relevant guidance at WP:Non-free content. This essay predominantly deals with historical personalities from older periods, where contemporary depictions (as far as they existed) would be in the public domain now.

While this essay mainly addresses images of individual persons, some of its advice also carries over to other historical topics, such as depictions of events, battles, etc.

Authentic portraits

For our purposes, a portrait is an artistic depiction of a person that purports to provide an individualized, authentic representation of that person's unique looks, based either directly or indirectly on a witness's first-hand experience of their physical appearance.

Where portraits exist, as sculptures, paintings or drawings, they are of course the first and most obvious choice for illustrating an article.

Unfortunately, for the large majority of notable individuals in history, there are no portraits. Except for some very few cultures (e.g. the ancient Egyptians and Romans), most historical civilizations had no notion of producing portraits in this sense at all. In the European/Western tradition, painted portraits have been common since the late Middle Ages. Before that, the search for a true portrait will usually draw a blank.

Contemporary stylized depictions

While most historical cultures didn't produce portraits in the true sense, many did produce other kinds of depictions of individual persons. Depictions of rulers on coins, miniatures in medieval bookpainting and ancient monuments are examples of such practices. In many cases, these are so heavily stylized that they can't serve to provide a realistic sense of what the person actually looked like, and aren't intended to. Often they are also not exactly contemporary with the person's lifetime and not based on an artist's first-hand memory of their looks.

While such items are, strictly speaking, useless in showing us what a person looked like, they are nevertheless generally acceptable as illustrations in Wikipedia articles. Insofar as they were produced in the context of the subject's own cultural sphere and close to their lifetime, they can provide, if nothing else, a sense of the subject's historical role and cultural context and how they were seen and imagined by contemporaries.

Conventionalized traditional depictions

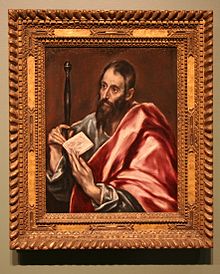

Sometimes there are conventionalized traditions of imaginary portraiture of historical figures. This is most notably the case in some religious traditions, such as Christian hagiographic art. Even though such depictions are usually entirely imaginary, and often heavily ahistorical, they can be suitable for our articles because the history of the religious veneration of the figure in question is just as much part of the topic of the article as their actual historical existence.

Independently notable artworks

Another case where an imaginary depiction can easily make sense in an article is if it is a well-known, high-quality artwork that is independently notable as such. While such an artwork may tell us little about the historical person directly, the fact that it was created will usually be an easily justifiable part of our coverage, typically in some kind of "legacy" section. The inclusion of such an image should normally be accompanied with sourced text that contextualizes it.

Artwork illustrating later views of a person

Similarly, an imaginary depiction can be a valuable addition to an article if it illustrates a notable aspect of how some later era saw the figure in question, as for instance when a medieval ruler is represented in a 19th-century painting or statue. Often, such depictions carry some heavy ideological baggage; they might be expressions of historical hero-worship, attempting to promote the person in question as a foundational figure in a country's history for nationalist purposes, and so on. For this reason, such depictions ought never to be used in articles without being contextualized through well-sourced textual coverage of how and why they were created.

Modern illustrators' works

Often, imaginary illustrations exist that fall into none of the groups above. These might be book illustrations from the 19th or early 20th century, from a time when popular non-fiction books were often illustrated with cheaply made hand-drawn artwork, now free of copyright. Or they might be illustrations by yet more recent modern artists, or even by Wikipedia users, who have released them under a free license. While we normally value and appreciate user-created or other free modern artwork offered to Wikipedia, we need to be aware that these works may present the same problems as those mentioned in the sections above, while not offering any of their encyclopedic value. Their concrete information value regarding the historical figure as such is usually zero, as they are entirely the product of the artist's imagination. More often than not, their artistic and aesthetic quality is low; they may be esthetically unoriginal, derivative and technically mediocre. Even worse, the problem of ideological baggage is very frequently an issue and may be quite as problematic, or even more so, than in the more notable cases mentioned above.

Among the tell-tale signs of ideological POV messages carried in such depictions is a tendency of stereotypically emphasizing a male historical figure's imagined virile good looks, presenting a ruler or military figure in a stereotypically heroic pose, and so on. Such aesthetic choices mean injecting a highly problematic, covert POV message into an article. At the same time, unlike in the cases of independently notable depictions, there is typically no sourced coverage that could contextualize and offset such covert messages. Since the artist is non-notable, their artistic imagination will not have been analyzed and written about in reliable sources, so we have nothing to explain and hedge the image with, and would be left with just letting it speak for itself and spread its ideological message freely.

Such images may therefore be not merely useless, but actually harmful to the encyclopedia, and should be avoided.

Non-free modern depictions

Non-free copyrighted depictions of older figures are usually excluded under the non-free content rules of Wikipedia, unless they are artistically notable works that are the subject of sourced encyclopedic coverage in themselves. Otherwise, in addition to carrying all the problems and dangers described above, they also invariably fall foul of the replaceability criterion: if one artist could create an imaginary depiction of the person in question (without possessing any privileged knowledge of what they looked like that other people do not also have), then anybody else, including you and me, could do the same.

As absurd as it sounds, there have been cases where Wikipedians desperate for an image of a person have resorted not to imaginary portraits of that person themselves, but to portraits of somebody else entirely, on the argument that it was at least a person from a similar time and age, so "probably" that's what the actual article subject "might have looked like". In at least one case, there was even a notable, publicly published model for this: Scientists eager to "reconstruct" what Jesus "might" have looked like, took a real skull from some random real individual, whose only connection to Jesus was that he lived at roughly the same time and place, and did a forensic reconstruction of that random guy's face. This was then touted publicly as a reconstruction of what Jesus "might have looked like" [1].

Such attempts are, obviously, bollocks: within each population on earth, individual physical differences between people are huge, and almost certainly larger than the difference between a hypothetical "average" representative of that population and the corresponding average of some other neighbouring group. Taking the looks of one random individual to illustrate the "likely" physique of another from the same population is nothing short of hopeless. You could just as well take a portrait of Claudia Schiffer and pass it off as a representation of what Angela Merkel looks like (after all, they were born in the same century and in the same country, so they are likely to resemble each other, right?) Or why not go ahead and use a single photograph of a random Chinese person as an imaginary portrait in every infobox of every historical Chinese personality at once? (After all, all Chinese people look the same, right?)

So, don't do that.

Other historical image topics

While we have so far spoken only of depictions of individual persons, many of the same issues also apply to other images with historical content, such as depictions of historical scenes, events, battles and so forth. Similar caution should be exercised with regard to non-contemporary and modern artistic depictions as with imaginary portraits.

General Dos and Don'ts

- Never include images if you don't know their provenance. Many alleged historical depictions float around on the internet without proper source documentation. Even if you know they are old enough to be free of copyright, if you don't know where they ultimately are from, they are useless for an encyclopedia.

- Never include an imaginary depiction merely because you have seen it on lots of websites out there. Sometimes an association of an historical personality with a low-quality, unauthentic depiction becomes entrenched on the Internet simply because people on websites and web forums keep copying it from one place to another for lack of anything better. A reasonable encyclopedia should not contribute to this.

- If you are using a non-photographic depiction at the top of an article (e.g. in an infobox), always include an informative image caption that explains what it is.

- Never call an image a "portrait" if it isn't really one. Never make it appear as if the image was meant to show what a person really looked like, when it isn't.

- If you are using an image not as a real portrait but as an illustration of later cultural views of that person, consider not using it at the top of the article but somewhere else in the text where that aspect is discussed.

- Never include an image merely for the sake of not leaving the infobox empty. A Wikipedia article can live quite well without a colourful spot in the top right corner, and if there's nothing legitimate and encyclopedically useful to illustrate, then don't pretend otherwise.

See also

- Wikipedia:Image use policy

- Wikipedia:Manual of Style/Images

- de:Wikipedia:Historische Bilder (in German) (related guideline on the German Wikipedia)