User:Esterbka/sandbox

| This is a user sandbox of Esterbka. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

Current Excerpt from "Hoplite" 3rd paragraph

The origins of the hoplite are obscure, and no small matter of contention amongst historians. Traditionally, this has been dated to the 8th century BC, and attributed to Sparta; but more recent views suggest a later date, towards the 7th century BC [citation needed].

What I'm adding

Slightly incorrect information, and a needed citation.

New Excerpt

The origins of the hoplite are obscure, and no small matter of contention amongst historians. Traditionally, this has been dated to the 8th century BC, and attributed to Sparta; but more recent views suggest a later date, towards 800 BC and has been used to explain the break down of the aristocratic Greek state[1].

Current Excerpt from "Hoplite warfare" 2nd paragraph

If battle was refused by one side, they would retreat to the city, in which case the attackers generally had to content themselves with ravaging the countryside around, since the campaign season was too limited to attempt a siege.[citation needed]

What I'm adding

More information about battle protocol and a citation for the fact about battle refusal.

New Excerpt

If battle was refused by one side, they would retreat to the city, in which case the attackers generally had to content themselves with ravaging the countryside around, since the campaign season was too limited to attempt a siege. Following protocol, battle was usually agreed upon by both sides.[2]

Current Excerpt from The Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War[edit]

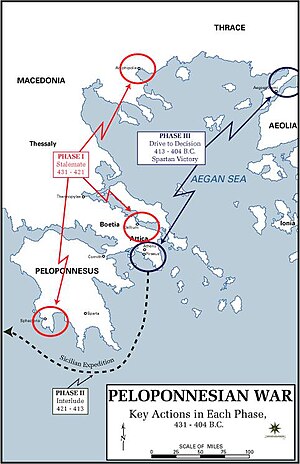

The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC), was fought between the Athenian dominated Delian League and the Spartan dominated Peloponnesian League. The increased manpower and financial resources increased the scale, and allowed the diversification of warfare. Set-piece battles during this war proved indecisive and instead there was increased reliance on naval warfare, and strategies of attrition such as blockades and sieges. These changes greatly increased the number of casualties and the disruption of Greek society.

Whatever the proximal causes of the war, it was in essence a conflict between Athens and Sparta for supremacy in Greece. The war (or wars, since it is often divided into three periods) was for much of the time a stalemate, punctuated with occasional bouts of activity. Tactically the Peloponnesian war represents something of a stagnation; the strategic elements were most important as the two sides tried to break the deadlock, something of a novelty in Greek warfare.

Building on the experience of the Persian Wars, the diversification from core hoplite warfare, permitted by increased resources, continued. There was increased emphasis on navies, sieges, mercenaries and economic warfare. Far from the previously limited and formalized form of conflict, the Peloponnesian War transformed into an all-out struggle between city-states, complete with atrocities on a large scale; shattering religious and cultural taboos, devastating vast swathes of countryside and destroying whole cities.[3]

From the start, the mismatch in the opposing forces was clear. The Delian League (hereafter 'Athenians') were primarily a naval power, whereas the Peloponnesian League (hereafter 'Spartans') consisted of primarily land-based powers. The Athenians thus avoided battle on land, since they could not possibly win, and instead dominated the sea, blockading the Peloponnesus whilst maintaining their own trade. Conversely, the Spartans repeatedly invaded Attica, but only for a few weeks at a time; they remained wedded to the idea of hoplite-as-citizen. Although both sides suffered setbacks and victories, the first phase essentially ended in stalemate, as neither league had the power to neutralise the other. The second phase, an Athenian expedition to attack Syracuse in Sicily achieved no tangible result other than a large loss of Athenian ships and men.

In the third phase of the war however the use of more sophisticated stratagems eventually allowed the Spartans to force Athens to surrender. Firstly, the Spartans permanently garrisoned a part of Attica, removing from Athenian control the silver mine which funded the war effort. Forced to squeeze even more money from her allies, the Athenian league thus became heavily strained. After the loss of Athenian ships and men in the Sicilian expedition, Sparta was able to foment rebellion amongst the Athenian league, which therefore massively reduced the ability of the Athenians to continue the war.

Athens in fact partially recovered from this setback between 410-406 BC, but a further act of economic war finally forced her defeat. Having developed a navy that was capable of taking on the much-weakened Athenian navy, the Spartan general Lysander seized the Hellespont, the source of Athens' grain. The remaining Athenian fleet was thereby forced to confront the Spartans, and were decisively defeated. Athens had little choice but to surrender; and was stripped of her city walls, overseas possessions and navy. In the aftermath, the Spartans were able to establish themselves as the dominant force in Greece for three decades.

What I'm adding

Further clarification on the causes of the war.

- ^ Krentz, Peter. “Fighting by the Rules: The Invention of the Hoplite Agôn.” Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, vol. 71, no. 1, 2002, pp. 23–39. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3182059.

- ^ Krentz, Peter. “Fighting by the Rules: The Invention of the Hoplite Agôn.” Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, vol. 71, no. 1, 2002, pp. 23–39. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3182059.

- ^ Kagan. The Peloponnesian War. pp. XXIII–XXIV.