User:Eeng1/sandbox

Removed the legacy section from the main article, placed it here in case anyone wants to add it back in or expand upon it.

Legacy[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2017) |

A number of streets and squares in major Russian cities are named after the plan, including the First Five-Year Plan Street in Chelyabinsk and Volgograd, and First Five-Year Plan Square in Yekaterinburg.

Article Draft [Agricultural Collectivization of First Five Year Plan][edit]

- Original Article

The first five-year plan also began a period of rapid agricultural collectivization in the Soviet Union. One reason for the collectivization of Soviet agriculture was to increase the number of industrial workers for the new factories. Soviet officials also believed that collectivization would increase crop yields and help fund other programs. The Soviets enacted a land decree in 1917 that eliminated private ownership of land. This agricultural collectivization was however a failure for the Soviets. Vladimir Lenin tried to establish removal of grain from wealthier peasants after the initial failure of state farms but this was also unsuccessful. Peasants were mainly concerned for their own well being and felt that the state had nothing of necessity to offer for the grain. This stock piling of grain by the peasantry left millions of people in the city hungry leading Lenin to establish his New Economic Policy to keep the economy from crashing. NEP was based more on capitalism and not socialism, which is the direction the country wanted to head toward. Stalin's extreme push during his first five year plan and force collectivization was partly in response to his distaste for the NEP.

At the end of 1929 the Soviets asserted themselves to forming collectivized peasant agriculture, but the “Kulaks” had to be “liquidated as a class,” because of their resistance to fixed agricultural prices.Resulting from this, the party behavior became uncontrolled and manic when the party began to requisition food from the countryside. Kulaks were executed, exiled or deported, based on their level of resistance to collectivization. The kulaks who were considered "counter-revolutionary" were executed or exiled, those who opposed collectivization were deported to remote regions and the rest were resettled to non arable land in the same region. In the years following the agricultural collectivization, the reforms would disrupt the Soviet food supply. In turn, this disruption would eventually lead to famines for the many years following the first five-year plan, with 3-4 million dying from starvation in 1933.

- Edited Article (Work-in-progress)

Agricultural Collectivization was integral to the first five-year plan. There were many goals for agricultural collectivization, one of them being that the collectivization would spurn the economy. The theory was that peasants would buy industrial goods to use for expansion of crops, which in turn would yield more agricultural production and contribute to expanding the industry. However, this method was not as successful as anticipated. Many peasants could not endure the poor living conditions generated by the forced collectivization and resorted to moving to the urban areas to become industrial workers. [1]

Testing out links.

| This is a user sandbox of Eeng1. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

Additional Sources & Possible Additions[edit]

I think the following sources could be of help in expanding both sections dealing with the success and failure of the plan (also these section titles should be edited for consistency [already did this]); in particular, the article "Soviet Famine of 32-34" deals with how the famine came about largely due to the failures of the first five-year plan, and the article "overambitious first Soviet Five-Year Plan" deals with how the plan did and/or did not exceed/meet the targeted goals of the plan. Also, these articles could possibly help to expand the "growth of industry" section:

Hunter, Holland. "The Overambitious First Soviet Five-Year Plan." Slavic Review : Interdisciplinary Quarterly of Russian, Eurasian and East European Studies 32, no. 2 (1973): 237-57. doi: 10.2307/2495959

Davies, R. W., and Wheatcroft, S. G. "Further Thoughts on the First Soviet Five-Year Plan." Slavic Review : Interdisciplinary Quarterly of Russian, Eurasian and East European Studies 34, no. 4 (1975): 790-802. doi: 10.2307/2495728

Dalrymple, Dana G. "The Soviet Famine of 1932-1934." Soviet Studies : A Quarterly Review of the Social and Economic Institutions of the USSR 15, no. 3 (1964): 250-84.

Viola, Lynne. "The "25,000ers": A Study in a Soviet Recruitment Campaign During the First Five Year Plan." Russian History 10, no. 1 (1983): 1-30. doi: 10.1163/187633183X00019

Mally, Lynn. "Shock Workers On the Cultural Front: Agitprop Brigades in the First Five-Year Plan." Russian History 23, no. 1-4 (1996): 263-76. doi: 10.1163/187633196X00178

for easy DOI reference

Hunter, Holland. "The Overambitious First Soviet Five-Year Plan." Slavic Review : Interdisciplinary Quarterly of Russian, Eurasian and East European Studies 32, no. 2 (1973): 237-57. doi: 10.2307/2495959

Maurice Dobb (1953) Rates of growth under the five‐year plans, Soviet

Studies, 4:4, 364-385, DOI: 10.1080/09668135308409870

Millar, James R. “Mass Collectivization and the Contribution of Soviet Agriculture to the First Five-Year Plan: A Review Article.” Slavic Review, vol. 33, no. 4, 1974, pp. 750–766., doi:10.2307/2494513.

Stone, David R. “The First Five-Year Plan and the Geography of Soviet Defence Industry.” Europe-Asia Studies, vol. 57, no. 7, 2005, pp. 1047–1063., doi:10.1080/09668130500302756.

Article Draft [Successes of the first five-year plan][edit]

- Original Article

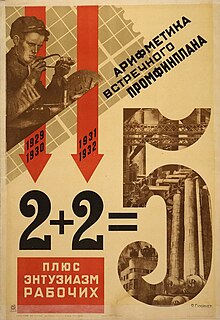

The success of the first five-year plan was that the Soviet Union began its journey to becoming a world superpower through industrialization. Stalin declared the plan a success at the beginning of 1933, noting the creation of several heavy industries where none had existed, and the plan was fulfilled in four years and three months instead of five years. Walter Duranty received the 1932 Pulitzer Prize for Correspondence for his coverage of the first five-year plan. Duranty's coverage of the five-year plan's many successes led directly to Franklin Roosevelt officially recognizing the Soviet Union in 1933.

The first five-year plan also began to prepare the Soviet Union to win in the Second World War. Without the initial five-year plan, and the ones that followed, the Soviet Union would not have been prepared for the German invasion in 1941. Due to the rapid industrialization of the plan, the Soviet Union was able to build the weapons it needed to defeat the Germans in 1945.

- Edited Article [Work in progress]

Although many of the goals set by the plan were not fully met, there were several economic sectors that still saw large increases in their output. Areas like capital goods increased 158%, consumer goods increased by 87%, and total industrial output increased by 118%.[2] In addition, despite the difficulties that agriculture underwent throughout the plan, the Soviets recruited more than 70,000 volunteers from the cities to help collectivize and work on farms in the rural areas.[3]

The largest success of the first five-year plan however, was the Soviet Union beginning its journey to become an economic and industrial superpower.[4] Stalin declared the plan a success at the beginning of 1933, noting the creation of several heavy industries where none had existed, and stating that the plan was fulfilled in four years and three months instead of five years. The plan was also lauded by some members of the western media, and although much of his reporting was later disputed, New York Times reporter Walter Duranty received the 1932 Pulitzer Prize for Correspondence for his coverage of the first five-year plan. Duranty's coverage of the five-year plan's many successes led directly to Franklin Roosevelt officially recognizing the Soviet Union in 1933.

The first five-year plan also began to prepare the Soviet Union to win in the Second World War. Without the initial five-year plan, and the ones that followed, the Soviet Union would not have been prepared for the German invasion in 1941. Due to the rapid industrialization of the plan, as well as the strategic construction of arms manufacturers in areas less vulnerable to future warfare[5], the Soviet Union was able to build the weapons it needed to defeat the Germans in 1945.

- ^ Mccauley, Martin (2013). Stalin and Stalinism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-4058-7436-6.

- ^ Dobb, Maurice (2007). "Rates of growth under the five‐year plans". Soviet Studies. 4 (4): 364–385. doi:10.1080/09668135308409870. ISSN 0038-5859.

- ^ Millar, James R. (2017). "Mass Collectivization and the Contribution of Soviet Agriculture to the First Five-Year Plan: A Review Article". Slavic Review. 33 (4): 750–766. doi:10.2307/2494513. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2494513.

- ^ Hunter, Holland (2017). "The Overambitious First Soviet Five-Year Plan". Slavic Review. 32 (2): 237–257. doi:10.2307/2495959. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2495959.

- ^ Stone, David R. (2006). "The First Five-Year Plan and the Geography of Soviet Defence Industry". Europe-Asia Studies. 57 (7): 1047–1063. doi:10.1080/09668130500302756. ISSN 0966-8136. S2CID 153925109.

Article Draft [Failures of the First Five Year Plan][edit]

- Original Article

The failures of the first five-year plan were numerous. The first plan was destined for failure from the beginning because of unrealistic quotas set for industrialization that, in reality, would not be met for decades to come. One of the problems was the goals for the plans were not set and those that were, were constantly changed. Each time one quota was met, it was revised and made larger, which quickly eliminated any chance of the plan succeeding.

Secondly, the collectivization created a large-scale famine in the Soviet Union in which over 10 million died. These famines were among the worst in history and created scars which would mark the Soviet Union for many years to come and incense a deep hatred of Russians by Ukrainians, Tartars, and many other ethnic groups. Hitler used the disregard of human life by Russians toward non-Russians as one of his bases to conduct Operation Barbarossa and gain initial victories over the Russians. These failures would lead to the plan being discontinued after four years instead of five.

- Edited Article (Work in Progress)

With the first five-year plan came failures as well. The great push for industrialization cause quotas to consistently be looked at and adjusted. Quotas expecting to reach 235.9 percent output and labor to increase by 110 percent was unrealistic in the time frame they allotted for.[1] Work life was rough since unions were being shut down which meant workers were no longer allowed to strike and not protected from being fired or dismissed from work for reasons such as being late or just missing a day.[1]

Farming areas were greatly effected by bad harvests in the years 1932 to 1933, leading to a great famine. This famine led many Russians to relocate to find food, jobs, and shelter outside of their small villages which caused many towns to become overpopulated. Their diet consisted of bread but there was a major decrease in the amount of meat and diary they were receiving if any at all.[1] Aside from the three to four million people dying because of starvation or even freezing to death because of waiting in line for rations, people were not wanting or unable to have children which assisted in the decrease of the population.[2]

Fitzpatrick, S. (1999). Everyday Stalinism : Ordinary life in extraordinary times : Soviet Russia in the 1930s. (48-50)

Pauley, Bruce F., Pauley, Bruce F, Ebrary., Inc, & MyiLibrary. (2015). Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini : Totalitarianism in the twentieth century(4th ed.).

- ^ a b c F., Pauley, Bruce (2014). Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini : Totalitarianism in the Twentieth Century (4th ed.). Hoboken: Wiley. ISBN 9781118765869. OCLC 883570079.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sheila., Fitzpatrick (1999). Everyday Stalinism : ordinary life in extraordinary times : Soviet Russia in the 1930s. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195050011. OCLC 567928000.

Article Draft [Industrial Achievements of The First Five Year Plan][edit]

During October 1928 and December 1932, being thought of as the most crucial time for Russian industrialization[1] which was 80% of the total investment of the First Five Year Plan. These industries included: timber, oil, cement, coal, metals, electricity, iron & steel. During this time in Stalingrad and Kharkov, large new industrial complexes were being built. Despite the fact that during this time, there was a lack of skilled workers and the fact that the great depression was driving down the the price of grain and raw material, which could be a reflection of the forced collectivization program happening in the countryside. Collectivization helped grow the industrial sector becasue it created a need for tractor factories to keep up with the needs of mechanized agriculture (find reliable source) The Soviet Unions achievements were tremendous during the First Five Year Plan, which yielded a fifty-percent increase in industrial output[2]. (input information about the huge expectations in output for the first five year plan, that were not met until after ww2)

Successful Factors:

Coal & Iron -output doubled

Steel Production: Increased by one-third

Engineering Industry: developed & increased output of machine tools and turbnes

Article Draft [Agricultural collectivization][edit]

- Original ARTICLE

The first five-year plan also began a period of rapid agricultural collectivization in the Soviet Union. One reason for the collectivization of Soviet agriculture was to increase the number of industrial workers for the new factories.[1] Soviet officials also believed that collectivization would increase crop yields and help fund other programs.[1] The Soviets enacted a land decree in 1917 that eliminated private ownership of land. This agricultural collectivization was however a failure for the Soviets. Vladimir Lenin tried to establish removal of grain from wealthier peasants after the initial failure of state farms but this was also unsuccessful. Peasants were mainly concerned for their own well being and felt that the state had nothing of necessity to offer for the grain. This stock piling of grain by the peasantry left millions of people in the city hungry leading Lenin to establish his New Economic Policy to keep the economy from crashing. NEP was based more on capitalism and not socialism, which is the direction the country wanted to head toward. Stalin's extreme push during his first five year plan and force collectivization was partly in response to his distaste for the NEP.[2]

At the end of 1929 the Soviets asserted themselves to forming collectivized peasant agriculture, but the “Kulaks” had to be “liquidated as a class,” because of their resistance to fixed agricultural prices.[3] Resulting from this, the party behavior became uncontrolled and manic when the party began to requisition food from the countryside.[3] Kulaks were executed, exiled or deported, based on their level of resistance to collectivization[4]. The kulaks who were considered "counter-revolutionary" were executed or exiled, those who opposed collectivization were deported to remote regions and the rest were resettled to non arable land in the same region.[4] In the years following the agricultural collectivization, the reforms would disrupt the Soviet food supply.[3] In turn, this disruption would eventually lead to famines for the many years following the first five-year plan, with 3-4 million dying from starvation in 1933.[5]

- EDITED ARTICLE (work in progress)

The first five-year plan also began a period of rapid agricultural collectivization in the Soviet Union. One reason for the collectivization of Soviet agriculture was to increase the number of industrial workers for the new factories.[1] Following rapid industrialization was urbanization; the anticipated growth in consumption led to collectivization. Collectivization being a system in which grain was taken from the peasants, with little to no compensation.[6] To be more specific to the FYP, collectivization was the recruitment of peasants, and then later on whole villages to join the kolkhoz. Once they joined the kolkhoz, land became communal, which allowed for more crops to be farmed, with land bednyak and serednyak had not had access to prior; this become, more, a state reform of peasant agriculture[7]. Soviet officials also believed that collectivization would increase crop yields and help fund other programs.[1] The Soviets enacted a land decree in 1917 that eliminated private ownership of land. This agricultural collectivization was however a failure for the Soviets. Those supported collectivization were the two lowest peasant groups: bednyak, or poor peasants; serednyak, or mid-income peasants[8]. Vladimir Lenin tried to establish removal of grain from wealthier peasants after the initial failure of state farms but this was also unsuccessful. Peasants were mainly concerned for their own well being and felt that the state had nothing of necessity to offer for the grain. This stock piling of grain by the peasantry left millions of people in the city hungry leading Lenin to establish his New Economic Policy to keep the economy from crashing. NEP was based more on capitalism and not socialism, which is the direction the country wanted to head toward. Stalin's extreme push during his first five year plan and force collectivization was partly in response to his distaste for the NEP.[9]

At the end of 1929 the Soviets asserted themselves to forming collectivized peasant agriculture, but the “Kulaks” had to be “liquidated as a class,” because of their resistance to fixed agricultural prices.[3] Resulting from this, the party behavior became uncontrolled and manic when the party began to requisition food from the countryside.[3] Kulaks were executed, exiled or deported, based on their level of resistance to collectivization[4]. The kulaks who were considered "counter-revolutionary" were executed or exiled, those who opposed collectivization were deported to remote regions and the rest were resettled to non arable land in the same region.[4] In the years following the agricultural collectivization, the reforms would disrupt the Soviet food supply.[3] In turn, this disruption would eventually lead to famines for the many years following the first five-year plan, with 3-4 million dying from starvation in 1933.[5]

- ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

Library of Congresswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ McCauley, Martin (2008). Stalin and Stalinism (revised 3rd ed.). Pearson Education Limited. p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e f Fitzpatrick, Shelia (1994). The Russian Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 136.

- ^ a b c d McCauley, Martin (2013). Stalin and Stalinism. New York: Rutledge. p. 40.

- ^ a b Fitzpatrick, Shelia (2008). The Russian Revolution (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 140.

- ^ "Collective Farms and Russian Peasant Society, 1933-1937: The Stabilization of the Kolkhoz Order". ProQuest Dissertations Publishing: 744. 1990.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Sheila (2010). ""The Question of Social Support for Collectivization."". Russian History. 37 (2): 156. doi:10.1163/187633110X494670.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Sheila (2010). ""The Question of Social Support for Collectivization."". Russian History. 37 (2): 153–177. doi:10.1163/187633110X494670.

- ^ McCauley, Martin (2008). Stalin and Stalinism (revised 3rd ed.). Pearson Education Limited. p. 17.