User:Dead Mary/sandbox1

History[edit]

Germanic tribes and Frankish Empire[edit]

The Germanic tribes are thought to date from the Nordic Bronze Age or the Pre-Roman Iron Age. From southern Scandinavia and north Germany, they expanded south, east and west from the 1st century BC, coming into contact with the Celtic tribes of Gaul as well as Iranian, Baltic, and Slavic tribes in Central and Eastern Europe.[1] Under Augustus, Rome began to invade Germania (an area extending roughly from the Rhine to the Ural Mountains). In AD 9, three Roman legions led by Publius Quinctilius Varus were defeated by the Cheruscan leader Arminius. By AD 100, when Tacitus wrote Germania, Germanic tribes had settled along the Rhine and the Danube (Limes Germanicus), occupying most of the area of modern Germany; Austria, southern Bavaria and the western Rhineland, however, were Roman provinces.[2]

In the 3rd century a number of large West Germanic tribes emerged: Alemanni, Franks, Chatti, Saxons, Frisii, Sicambri, and Thuringii. Around 260, the Germanic peoples broke into Roman-controlled lands.[3] After an invasion by the Huns in 375, and with the decline of Rome from 395, Germanic tribes moved further south-west. Simultaneously several large tribes formed in what is now Germany and displaced the smaller Germanic tribes. Large areas (known since the Merovingian period as Austrasia) were occupied by the Franks, and Northern Germany was ruled by the Saxons and Slavs.[2]

Holy Roman Empire[edit]

On 25 December 800, the Frankish king Charlemagne was crowned emperor and founded the Carolingian Empire, which was divided in 843.[4] Frankish rule was extended under Charlemagne's sons and then later by his grandson 'Louis the German' who was referred to as Germanicus, but the Carolingian Empire he ruled was the old Germania (to the right of the Rhine) and this geographical portion of the east Frankish kingdom additionally subsumed an assemblage of Alamanni, Bavarians, Main Franks, Saxons, Thuringians, Slavic tribes from the Baltic and Adriatic, and even some Pannonian Avars.[5] As such, the Holy Roman Empire comprised the eastern portion of Charlemagne's original kingdom and emerged as the strongest, some of this consequent to the aforementioned reign of 'Louis the German' and its extended cohesion was achieved through the unification efforts of Conrad of Franconia (911-918).[6] Its territory stretched from the Eider River in the north to the Mediterranean coast in the south.[4] Under the reign of the Ottonian emperors (919–1024), several major duchies were consolidated, and the German king Otto I was crowned Holy Roman Emperor of these regions in 962. In 996 Gregory V became the first German Pope, appointed by his cousin Otto III, whom he shortly after crowned Holy Roman Emperor.[7] The Holy Roman Empire absorbed northern Italy and Burgundy under the reign of the Salian emperors (1024–1125), although the emperors lost power through the Investiture Controversy.[8]

Under the Hohenstaufen emperors (1138–1254), the German princes increased their influence further south and east into territories inhabited by Slavs, preceding German settlement in these areas and further east (Ostsiedlung). Northern German towns grew prosperous as members of the Hanseatic League.[9] Starting with the Great Famine in 1315, then the Black Death of 1348–50, the population of Germany plummeted.[10] The edict of the Golden Bull in 1356 provided the basic constitution of the empire and codified the election of the emperor by seven prince-electors who ruled some of the most powerful principalities and archbishoprics.[11]

Martin Luther publicised The Ninety-Five Theses in 1517 in Wittenberg, challenging the beliefs of the Roman Catholic Church and initiating the Protestant Reformation. A separate Lutheran church became the official religion in many German states after 1530. Religious conflict led to the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), which devastated German lands.[12] The population of the German states was reduced by about 30%.[13] The Peace of Westphalia (1648) ended religious warfare among the German states, but the empire was de facto divided into numerous independent principalities. In the 18th century, the Holy Roman Empire consisted of approximately 1,800 such territories.[14]

From 1740 onwards, dualism between the Austrian Habsburg Monarchy and the Kingdom of Prussia dominated German history. In 1806, the Imperium was overrun and dissolved as a result of the Napoleonic Wars.[15]

German Confederation and Empire[edit]

Following the fall of Napoleon, the Congress of Vienna convened in 1814 and founded the German Confederation (Deutscher Bund), a loose league of 39 sovereign states. Disagreement with restoration politics partly led to the rise of liberal movements, followed by new measures of repression by Austrian statesman Metternich. The Zollverein, a tariff union, furthered economic unity in the German states.[16] National and liberal ideals of the French Revolution gained increasing support among many, especially young, Germans. The Hambach Festival in May 1832 was a main event in support of German unity, freedom and democracy. In the light of a series of revolutionary movements in Europe, which established a republic in France, intellectuals and commoners started the Revolutions of 1848 in the German states. King Frederick William IV of Prussia was offered the title of Emperor, but with a loss of power; he rejected the crown and the proposed constitution, leading to a temporary setback for the movement.[17]

Conflict between King William I of Prussia and the increasingly liberal parliament erupted over military reforms in 1862, and the king appointed Otto von Bismarck the new Minister President of Prussia. Bismarck successfully waged war on Denmark in 1864. Prussian victory in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 enabled him to create the North German Confederation (Norddeutscher Bund) and to exclude Austria, formerly the leading German state, from the federation's affairs. After the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, the German Empire was proclaimed in 1871 in Versailles, uniting all scattered parts of Germany except Austria ([Kleindeutschland] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), or "Lesser Germany").

With almost two-thirds of its territory and population, Prussia was the dominating constituent of the new state; the Hohenzollern King of Prussia ruled as its concurrent Emperor, and Berlin became its capital.[17] In the [Gründerzeit] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) period following the unification of Germany, Bismarck's foreign policy as Chancellor of Germany under Emperor William I secured Germany's position as a great nation by forging alliances, isolating France by diplomatic means, and avoiding war. As a result of the Berlin Conference in 1884 Germany claimed several colonies including German East Africa, German South-West Africa, Togo, and Cameroon.[18] Under Wilhelm II, however, Germany, like other European powers, took an imperialistic course leading to friction with neighbouring countries. Most alliances in which Germany had previously been involved were not renewed, and new alliances excluded the country.[19]

The assassination of Austria's crown prince on 28 June 1914 triggered World War I. Germany, as part of the Central Powers, suffered defeat against the Allies in one of the bloodiest conflicts of all time. An estimated two million German soldiers died in World War I.[20] The German Revolution broke out in November 1918, and Emperor Wilhelm II and all German ruling princes abdicated. An armistice ended the war on 11 November, and Germany was forced to sign the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919. The treaty was perceived in Germany as a humiliating continuation of the war, and is often cited as an influence in the rise of Nazism.[21]

Weimar Republic and the Third Reich[edit]

At the beginning of the German Revolution in November 1918, Germany was declared a republic. However, the struggle for power continued, with radical-left Communists seizing power in Bavaria. The revolution came to an end on 11 August 1919, when the democratic Weimar Constitution was signed by President Friedrich Ebert.[23] An era of increasing national confidence, a very liberal cultural life and decade of economic prosperity followed - known as the Golden Twenties. Suffering from the Great Depression of 1929, the peace conditions dictated by the Treaty of Versailles, and a long succession of unstable governments, Germans increasingly lacked identification with the government in the early 1930s.[citation needed] This was exacerbated by a widespread right-wing [Dolchstoßlegende] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), or stab-in-the-back legend, which argued that Germany had lost World War I because of those who wanted to overthrow the government.[citation needed] The Weimar government was accused of betraying Germany by signing the Versailles Treaty.[citation needed]

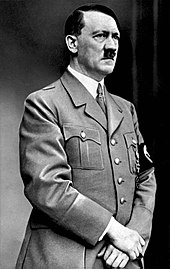

By 1932, the German Communist Party and the Nazi Party controlled the majority of Parliament, fuelled by discontent with the Weimar government. After a series of unsuccessful cabinets, President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933.[24] On 27 February 1933 the Reichstag building went up in flames, and a consequent emergency decree abrogated basic citizens' rights. An enabling act passed in parliament gave Hitler unrestricted legislative power. Only the Social Democratic Party voted against it, while Communist MPs had already been imprisoned.[25][26] Using his powers to crush any actual or potential resistance, Hitler established a centralised totalitarian state within months. Industry was revitalised with a focus on military rearmament.[27]

In 1935, Germany reacquired control of the Saar and in 1936 military control of the Rhineland, both of which had been lost in the Treaty of Versailles.[28] In 1938, Austria was annexed, and in 1939, Czechoslovakia was brought under German control. The invasion of Poland was prepared through the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact and Operation Himmler. On 1 September 1939 the German Wehrmacht launched a blitzkrieg on Poland, which was swiftly occupied by Germany and by the Soviet Red Army. The UK and France declared war on Germany, marking the beginning of World War II.[29] As the war progressed, Germany and its allies quickly gained control of most of continental Europe and North Africa, though plans to force the United Kingdom to an armistice or surrender failed. On 22 June 1941, Germany broke the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact and invaded the Soviet Union. Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor led Germany to declare war on the United States. The Battle of Stalingrad forced the German army to retreat on the Eastern front.[29]

In September 1943, Germany's ally Italy surrendered, and German troops were forced to defend an additional front in Italy. D-Day opened a Western front, as Allied forces advanced towards German territory. On 8 May 1945, the German armed forces surrendered after the Red Army occupied Berlin.[30]

In what later became known as The Holocaust, the Nazi regime enacted policies which directly persecuted many dissidents and minorities. Over 10 million civilians were murdered by the Nazis during the Holocaust, including six million Jews, between 220,000 and 1,500,000 Romani people, 275,000 persons with mental and/or physical disabilities, thousands of Jehovah's Witnesses, thousands of homosexuals, and hundreds of thousands of members of the political and religious opposition.[31] 6 million Ukrainians and Poles and an estimated 2.8 million Soviet war prisoners were also killed by the Nazi regime and in total World War II was responsible for around 40 million deaths in Europe.[32]

German army war casualties were between 3.25 million and 5.3 million soldiers,[33] and between 1 and 3 million German civilians were killed.[34][35] Losing the war resulted in large territorial losses for Germany, the expulsion of about 15 million ethnic Germans from the former eastern territories of Germany and other formerly occupied countries. Germany suffered mass rape of German women[36] and the destruction of numerous major cities due to allied bombing during the war. After World War II, Nazis, former Nazis and others were tried for war crimes, including crimes related to the Holocaust, at the Nuremberg trials.[37]

East and West Germany[edit]

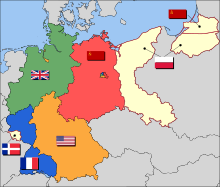

After the surrender of Germany, the remaining German territory and Berlin were partitioned by the Allies into four military occupation zones. Together, these zones accepted more than 6.5 million of the ethnic Germans expelled from eastern areas.[38] The western sectors, controlled by France, the United Kingdom, and the United States, were merged on 23 May 1949 to form the Federal Republic of Germany (Bundesrepublik Deutschland); on 7 October 1949, the Soviet Zone became the German Democratic Republic (Deutsche Demokratische Republik, or DDR). They were informally known as "West Germany" and "East Germany". East Germany selected East Berlin as its capital, while West Germany chose Bonn as a provisional capital, to emphasise its stance that the two-state solution was an artificial and temporary status quo.[39]

West Germany, established as a federal parliamentary republic with a "social market economy", was allied with the United States, the UK and France. Konrad Adenauer was elected the first Federal Chancellor (Bundeskanzler) of Germany in 1949 and remained in office until 1963. Under his and Ludwig Erhard's leadership, the country enjoyed prolonged economic growth beginning in the early 1950s, that became famous as the "economic miracle" (German: Wirtschaftswunder). West Germany joined NATO in 1955 and was a founding member of the European Economic Community in 1957.

East Germany was an Eastern Bloc state under political and military control by the USSR via the latter's occupation forces and the Warsaw Pact. Though East Germany claimed to be a democracy, political power was exercised solely by leading members (Politbüro) of the communist-controlled Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), supported by the Stasi, an immense secret service,[40] and a variety of sub-organisations controlling every aspect of society. A Soviet-style command economy was set up; the GDR later became a Comecon state.[41]

While East German propaganda was based on the benefits of the GDR's social programmes and the alleged constant threat of a West German invasion, many of its citizens looked to the West for freedom and prosperity.[42] The Berlin Wall, built in 1961 to stop East Germans from escaping to West Germany, became a symbol of the Cold War,[17] hence its fall in 1989, following democratic reforms in Poland and Hungary, became a symbol of the Fall of Communism, German Reunification and Die Wende.

Tensions between East and West Germany were reduced in the early 1970s by Chancellor Willy Brandt's [Ostpolitik] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). In summer 1989, Hungary decided to dismantle the Iron Curtain and open the borders, causing the emigration of thousands of East Germans to West Germany via Hungary. This had devastating effects on the GDR, where regular mass demonstrations received increasing support. The East German authorities unexpectedly eased the border restrictions, allowing East German citizens to travel to the West; originally intended to help retain East Germany as a state, the opening of the border actually led to an acceleration of the Wende reform process. This culminated in the Two Plus Four Treaty a year later on 12 September 1990, under which the four occupying powers renounced their rights under the Instrument of Surrender, and Germany regained full sovereignty. This permitted German reunification on 3 October 1990, with the accession of the five re-established states of the former GDR (new states or "neue Länder").[17]

German reunification and the EU[edit]

Based on the Berlin/Bonn Act, adopted on 10 March 1994, Berlin once again became the capital of the reunified Germany, while Bonn obtained the unique status of a Bundesstadt (federal city) retaining some federal ministries.[43] The relocation of the government was completed in 1999.[44]

Since reunification, Germany has taken a more active role in the European Union and NATO. Germany sent a peacekeeping force to secure stability in the Balkans and sent a force of German troops to Afghanistan as part of a NATO effort to provide security in that country after the ousting of the Taliban.[45] These deployments were controversial since, after the war, Germany was bound by domestic law only to deploy troops for defence roles.[46] In 2005, Angela Merkel became the first female Chancellor of Germany as the leader of a grand coalition.[17] Germany hosted the 2007 G8 summit in Heiligendamm, Mecklenburg. In 2009, a liberal-conservative coalition under Merkel assumed leadership of the country. In 2013, another grand coalition was established in a Third Merkel cabinet.

- ^ Claster, Jill N. (1982). Medieval Experience: 300–1400. New York University Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-8147-1381-5.

- ^ a b Fulbrook 1991, pp. 9–13.

- ^ Bowman, Alan K.; Garnsey, Peter; Cameron, Averil (2005). The crisis of empire, A.D. 193–337. The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 12. Cambridge University Press. p. 442. ISBN 0-521-30199-8.

- ^ a b Fulbrook 1991, p. 11.

- ^ Wolfram (1997), The Roman Empire and its Germanic Peoples, p. 11.

- ^ Peter Heather, Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2009),368.

- ^ Richard P. McBrien, Lives of the Popes: The Pontiffs from St. Peter to Benedict XVI, (HarperCollins Publishers, 2000), 138.

- ^ The lumping of Germanic people into the generic term 'Germans' has its roots in the Investiture Controversy according to historian Herwig Wolfram, who claims it was a defensive move made by the papacy to delineate them as outsiders, partly due to the papacy's insecurity and so as to justify counterattacks upon them. See: Herwig Wolfram, The Roman Empire and its Germanic Peoples (Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University Press, 1997), 11-13.

- ^ Fulbrook 1991, pp. 13–24.

- ^ Nelson, Lynn Harry. The Great Famine (1315–1317) and the Black Death (1346–1351). University of Kansas. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Fulbrook 1991, p. 27.

- ^ Philpott, Daniel (January 2000). "The Religious Roots of Modern International Relations". World Politics. 52 (2): 206–245. doi:10.1017/S0043887100002604. S2CID 40773221.

- ^ Macfarlane, Alan (1997). The savage wars of peace: England, Japan and the Malthusian trap. Blackwell. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-631-18117-0.

- ^ Gagliardo, G., Reich and Nation, The Holy Roman Empire as Idea and Reality, 1763–1806, Indiana University Press, 1980, p. 12-13.

- ^ Fulbrook 1991, p. 97.

- ^ Henderson, W. O. (January 1934). "The Zollverein". History. 19 (73): 1–19. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1934.tb01791.x.

- ^ a b c d e Cite error: The named reference

statewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Black, John, ed. (2005). 100 maps. Sterling Publishing. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-4027-2885-3.

- ^ Fulbrook 1991, pp. 135, 149.

- ^ Crossland, David (22 January 2008). "Last German World War I Veteran Believed to Have Died". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Lee, Stephen J. (2003). Europe, 1890–1945. Routledge. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-415-25455-7.

- ^ Schmitz-Berning, Cornelia (1998 (2000 reprint)). "Führer, Der Führer". Vokabular des Nationalsozialismus. Berlin. pp. 240–245. ISBN 9783110168884.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) Thamer, Hans-Ulrich (2003). "Beginn der nationalsozialistischen Herrschaft (Teil 2)". Nationalsozialismus I (in German). Bonn: Federal Agency for Civic Education. Retrieved 5 April 2012.President von Hindenburg died on 2 August 1934. The day before, the cabinet had approved a submission making Hitler his successor. The office of the president was to be dissolved and united with that of the chancellor under the name "Führer und Reichskanzler". However, this was in breach of the Enabling Act (shortened & paraphrased).

- ^ Fulbrook 1991, pp. 156–160.

- ^ Fulbrook 1991, pp. 155–158, 172–177.

- ^ "Das Ermächtigungsgesetz 1933" (in German). Deutsches Historisches Museum. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Stackelberg, Roderick (1999). Hitler's Germany: Origins, interpretations, legacies. Routledge. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-415-20115-5.

- ^ "Industrie und Wirtschaft" (in German). Deutsches Historisches Museum. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Fulbrook 1991, pp. 188–189.

- ^ a b Fulbrook 1991, pp. 190–195.

- ^ Steinberg, Heinz Günter (1991). Die Bevölkerungsentwicklung in Deutschland im Zweiten Weltkrieg: mit einem Überblick über die Entwicklung von 1945 bis 1990 (in German). Kulturstiftung der dt. Vertriebenen. ISBN 978-3-88557-089-9.

- ^ Niewyk, Donald L.; Nicosia, Francis R. (2000). The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust. Columbia University Press. pp. 45–52. ISBN 978-0-231-11200-0.

- ^ "Leaders mourn Soviet wartime dead". BBC News. 9 May 2005. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Rüdiger Overmans. Deutsche militärische Verluste im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Oldenbourg 2000. ISBN 3-486-56531-1

- ^ Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg, Bd. 9/1, ISBN 3-421-06236-6. Page 460 (This study was prepared by the German Armed Forces Military History Research Office, an agency of the German government)

- ^ Bonn : Kulturstiftung der Deutschen Vertriebenen, Vertreibung und Vertreibungsverbrechen, 1945–1948 : Bericht des Bundesarchivs vom 28. Mai 1974 : Archivalien und ausgewählte Erlebnisberichte / [Redaktion, Silke Spieler]. Bonn :1989 ISBN 3-88557-067-X. (This is a study of German expulsion casualties due to "war crimes" prepared by the German government Archives)

- ^ Beevor, Antony (2003) [2002]. Berlin: The downfall 1945. Penguin. pp. 31–32, 409–412. ISBN 978-0-14-028696-0.

- ^ Overy, Richard (17 February 2011). "Nuremberg: Nazis on Trial". BBC History. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Richard J. Evans, "The Other Horror, Review of Orderly and Humane: The Expulsion of the Germans After the Second World War, by R.M. Douglas", The New Republic, 25 June 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2012

- ^ Wise, Michael Z. (1998). Capital dilemma: Germany's search for a new architecture of democracy. Princeton Architectural Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-56898-134-5.

- ^ maw/dpa (11 March 2008). "New Study Finds More Stasi Spooks". Spiegel Online – english site (www.spiegel.de/international). Der Spiegel. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

189,000 people were informers for the Stasi – the former Communist secret police – when East Germany collapsed in 1989 – 15,000 more than previous studies had suggested. [...] about one in 20 members of the former East German Communist party, the SED, was a secret police informant.

- ^ Colchester, Nico (1 January 2001). "D-mark day dawns". Financial Times. London. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Protzman, Ferdinand (22 August 1989). "Westward Tide of East Germans Is a Popular No-Confidence Vote". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

Behind the mass flight, Western experts say, is widespread and deepening disillusionment with the Honecker leadership's policies, particularly the refusal to consider the type of economic and political changes taking place elsewhere in the Eastern Bloc.

- ^ "Gesetz zur Umsetzung des Beschlusses des Deutschen Bundestages vom 20. Juni 1991 zur Vollendung der Einheit Deutschlands" (in German). Bundesministerium der Justiz. 26 April 1994. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ "Brennpunkt: Hauptstadt-Umzug". Focus (in German). Munich. 12 April 1999. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Dempsey, Judy (31 October 2006). "Germany is planning a Bosnia withdrawal". International Herald Tribune. Paris. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Merz, Sebastian (November 2007). "Still on the way to Afghanistan? Germany and its forces in the Hindu Kush" (PDF). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. pp. 2, 3. Retrieved 16 April 2011.