User:Cynwolfe/clothing of the Roman Empire

Clothing and personal adornment in the Roman Empire reflected the diversity of peoples under Roman rule. Contrary to popular perception, the clothing worn by Romans during the Imperial era ordinarily was dark or colorful. The most common male attire seen daily throughout the Empire as a whole would have been tunics, trousers, and cloaks.[2] The toga was the distinctive national garment of the Roman male citizen, but it was heavy and impractical, worn mainly for political business and sacrifices, formal visits to one's patron, and court appearances.[3] The study of how Romans dressed in daily life is complicated by a lack of direct evidence, since portraiture may show the subject in clothing with symbolic value, and surviving textiles from the period are rare—only a few tunics and cloaks, and no togas.[4]

In a status-conscious society like that of the Romans, clothing, jewelry, and accessories gave immediate visual clues about the etiquette of interacting with the wearer.[5] Wearing the correct clothing was supposed to reflect a society in good order.[6] The jurist Ulpian (d. 228 AD) categorizes clothing on the basis of who may appropriately wear it: vestimenta virilia, "men's clothing," is defined as the attire of the paterfamilias, "head of household"; puerilia is clothing that serves no purpose other than to mark its wearer as a "child" (puer) or legal minor; muliebria are the garments that characterize a woman (mulier); communia, those that are worn "in common" and are not gender-specific; and familiarica, clothing for the familia, the subordinates in a household, such as slaves.[7]

Tunic[edit]

The basic garment for all Romans, regardless of gender or wealth, was the simple sleeved tunic (tunica), made from two rectangles of fabric sewn or fastened at the shoulders and usually belted. The length differed by wearer: a man's reached mid-calf, but a soldier's was somewhat shorter; a woman's fell to her feet, and a child's to its knees.[9] The tunics of poor people and laboring slaves were made from coarse wool in natural, dull shades, with the length determined by the type of work they did. Finer tunics were made of lightweight wool or linen. A man who belonged to the senatorial or equestrian order wore a tunic with two purple stripes (clavi) woven vertically into the fabric: the wider the stripe, the higher the wearer's status.[10] Other garments could be layered over the tunic.

-

Colorful tunics on boar hunters

-

Another stylish boar hunter

Toga[edit]

The Imperial toga, worn over a tunic, was a "vast expanse" of semi-circular white wool that could not be put on and draped correctly without assistance.[11] Augustus required office holders and male members of his family to wear a toga for official appearances in public.[12] In his work on oratory, Quintilian describes in detail how the public speaker ought to orchestrate his gestures in relation to his toga.[13] In art, the toga is shown with the long end dipping between the feet, a deep curved fold in front (the sinus, "pocket") and a bulbous flap (umbo) at the chest.[14] The drapery became more intricate and structured over time, with the cloth forming a tight roll (balteus) across the midsection in later periods.[15]

Varro says that originally men and women alike wore the toga, but if this is historically true, it is reflected mainly by the wearing of the toga praetexta by both boys and girls who had not yet come of age. The praetexta had a purple stripe that signified the wearer's inviolability, and was probably, like the toga in general, a special-occasion garment. After weddings, for instance, "praetextate" children led the couple to their new home.[16] When boys came of age, their rite of passage included taking off the praetexta and putting on the plain white toga virilis ("manly toga").[17] Roman girls only rarely depicted togate. A Roman girl would have stopped wearing the praetexta when she became a bride, whose attire for the wedding ceremony was determined in part by ritual custom and in part by wealth and taste.

The purple-striped praetexta was worn also by curule magistrates, and state priests conducting sacrifices.[18] The use of the color purple or purplish-red, from murex dye, was regulated by law. Over time, emperors developed the habit of wearing an all-purple toga (toga picta), a privilege from which all others were barred, and which had been reserved mainly for censorsCHECK and triumphing generals during the Republic.[19]

The basic toga represented civilian life in contrast to militarization.[20] The Praetorian Guard put on togas in the city to give themselves a civilian appearance.[21] For reasons that scholars continue to puzzle over, the only women who wore togas were prostitutes or others who had sexually compromised themselves. The wearing of the toga may signal that prostitutes were outside the social and legal category of "woman". [22] These togas may have been made of a flimsy, "see-through" fabric, and were favored also by effeminate men or passive homosexual males.[23]

The toga contabulata is a style found from the 2nd century onward. It appears on the Arch of Constantine in Rome and the base of the Obelisk of Theodosius in Constantinople. Probianus wears the contabulata on one side of the ivory diptych depicting him, and on the other a long tunic and the chlamys, a heavy Greek cloak.[24]

While campaigning for office, a politician wore a toga made whiter by chalk (toga candida), which made him a candidatus, hence the English word "candidate." Although elections lost their importance under the rule of emperors, Christians began to use candidatus metaphorically in phrases such as "candidates for heaven" and "candidate for God",[25] and to put on white garments after baptism.[26] Under the Christian emperors, the candidati were a corps of imperial guardsmen who dressed in white.[27]

Women's clothing[edit]

The characteristic garment of the Roman matron at the beginning of the Empire was a stola, a rectangular length of fabric draped over a tunic, but it quickly dropped out of fashion.[28] Livia, the wife of Augustus, promoted his moral programme of cultivating the traditional women's arts of spinning and weaving, but by the time of Nero, most women with the money to do so bought their clothes, and production within the familia was aimed mostly at clothing slaves and other low-status dependents of the household.[29]

Pallium[edit]

In the 2nd century, emperors and men of status are often portrayed wearing the pallium, an originally Greek mantle (himation) folded tightly around the body, in art requiring that the arms be held in a particular attitude. Later, women are similarly portrayed, as is the allegorical representation of Pudicitia, "Modesty". The Christian author Tertullian considered the pallium an appropriate garment both for Christians, in contrast to the toga, and for educated people, since it was associated with philosophers.[30] Expressing decorum and piety, the pallium often appears in portraits for funerary, commemorative, and honorary monuments.[31] By the 4th century, the toga had been more or less replaced by the pallium, a garment embodying social unity.[32]

-

couple

Trousers[edit]

Braccae, trousers, originally represented Gallic identity.[33] When Julius Caesar admitted citizen Gauls to the Roman senate in the mid-40s BC, he had been accused of allowing "trouser-wearing" barbarians to usurp the institution's dignity.[34] The practicality of braccae led Roman soldiers to wear them in northern climates,[35] but in Roman art they continued to represent barbarians, particularly the Germanic peoples. In 397 under the emperor Honorius, as a panic overtook the Empire in the face of barbarian incursions, anyone who appeared publicly in the city wearing trousers faced severe legal penalties.[36]

Dining attire[edit]

The synthesis or cenatoria was a colorful dinner ensemble that might be worn by any gender in an urban setting. It was a faux pas for a man to wear a synthesis as daytime attire, rather as if a modern-day lawyer wore a tuxedo to court. Paintings that show Romans semi-clothed at dinner are fictional or allegorical scenes, not real-life practice.[37]

At banquets and some celebratory occasions, men and women wore wreaths of greenery or flowers.[38]

Textiles[edit]

Wool was the most common fabric,[39] and their pastoral origins were so important to the Romans that they celebrated the founding of Rome on the same day (April 21) as the Parilia, a sheepherding festival. Linen. Cotton was known as the "Egyptian fiber." See Coan silk in Horace (I think) and the Augustan elegists

Textile production was a major source of employment. Both textiles and finished garments were traded among the peoples of the Empire, whose products were often named for them or a particular town[40] and catered to an upscale market.[41] Cheap and mid-priced clothing tended to be produced locally, since shipping added to the cost.[42] The Edict of Diocletian lists maximum prices for garments that carried particular "labels": the wool cloak called the sagum, made in Gaul, was priced at 8,000 denarii, while one from Africa cost 500.[43] Fine linen tunics could cost as much as 20 times as those for poor people, with military tunics priced in the md-range.[44]

Since clothing was expensive, many people of the lower classes would have worn patched and ragged garments. Centonarii were guild workers who specialized in textile production and the recycling of old clothes into pieced quilts, cloaks and saddle cloths.[45]

CAH vol. 12 p. 421 ff

Head coverings and hairstyles[edit]

Upperclass men went bareheaded most of the time, while women kept their heads covered in public. Women and girls wore their hair up, according to tradition bound by headbands (vittae) woven from wool, though these are rarely seen in art except in depictions of freedwomen, for whom they may have represented respectability. At funerals, the custom of head-covering was reversed: men covered theirs, but women let their hair loose and left it uncovered.[46]

Men conducted most religious rituals with a back fold or cowl of the toga drawn up over the head (capite velato); in art, this head covering is a symbol of piety (pietas).[47] The pilos or pilleus, worn by free workers, was a rounded or slightly conical cap pulled onto the head.[48] At the December festival of Saturnalia, the pilleus was worn as the "cap of freedom" by both slaves and their masters, to demonstrate the temporary egalitarianism of the holiday. Priests of Rome's oldest religious orders had ceremonial headgear.

Jewelry[edit]

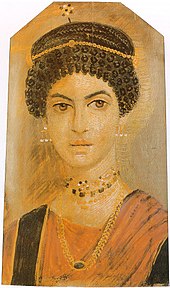

A great deal of Roman-era jewelry survives, and jewelry is often depicted in art. Italo-Roman jewelry from the 1st and 2nd centuries "geometric shapes, linear decoration, and an interest in color." Hellenistic-Roman jewelry "a stylized naturalism of Hellenistic animal and human motifs." these catories are those of Barbel Pfeiler. In 3rd century, "opus interrasile (openwork), a stronger polychromy, and the piling up of colored stone in more massive pieces." As indicated by the Fayum mummy portraits, a woman of the 1st century might wear "one simple gold chain with a golden pendant (often a crescent) or one jeweled necklace." Earrings are simple, as with a single pearl or gold hoops, disks or balls. In the 2nd century, she might wear two or three necklaces, one of them set with colored semiprecious stones. Earrings might have a horizontal bar from which three or four sets of pendants dangle. In the 4th century, coins or medallions are set in more massive neck rings. Snake bracelets remained popular throughout all four centuries.[49]

From the time of Tiberius, the wearing of a gold ring was granted to those who qualified as equestrians (third-generation freeborn, 400,000 sesterces).CHECK[50] Around 197 AD, Septimius Severus gave the honor to all soldiers. By the 2nd century, married women wore a gold ring.[51]

Augustus began the practice of wearing a signet ring that represented imperial authority, and later emperors sometimes gave rings as marks of imperial favor. [52] Men's jewelry was mainly confined to rings, especially a signet ring;[53] military awards, including the gold torque (torques or manxxxxxxx) and silver armlet (bracchalia);[54] belt buckles and fastenings; and in late antiquity, medallions (orbiculi) attached to clothing. Underage freeborn boys, including the sons of freedmen,CHECK wore the bulla, a necklace with an amulet meant to ward off from malevolent forces and signalled that .

-

ca. 300

-

Snake bracelets, 1st century AD

-

Snake ring, 1st century AD

-

Gallo-Roman earrings

-

Ring with gladiator. Bronze and red jasper, Roman art, 3rd century CE

-

Bracelet, 3rd century

-

Necklace, 3rd century

-

Getty necklace, 200–400

-

Coin necklace, helpfully undated

-

Constantius II medal, 347-55 AD

-

Valens medal, 375–78 AD

-

Bracelets from the Hoxne Hoard (4th-5th century)

-

or just two

-

assortment of rings

Footwear[edit]

Even footwear indicated a person's social status: patricians wore red and orange sandals, senators had brown footwear, consuls had white shoes, and soldiers wore heavy boots.

Studies in Ancient Technology on leather trade and shoemaking guilds[2]

-

Caliga (1st century BC–1st century AD)

-

Fragments of Roman footwear, ca. 200 AD

-

Leather slippers, 300–400 (at Getty but lacks context)

Personal grooming and cosmetics[edit]

xxxxxxx. An unkempt appearance might be meant to show off a philosophical disdain for artifice or superficiality. Seneca, however, advised men to cultivate a middle ground between a slovenly self-display that was ostentatious, and the overrefinement and effeminacy of depilating all body hair.[56]

-

toilette

-

Augustan cosmetics container

-

thermes de Sidi Ghrib, Musée National de Carthage

-

Perfume bottles in the shape of "flipflops" as pictured in the mosaic (top left)

-

Glass dual-tubed cosmetics container for kohl (Syria, 4th century)

-

Personal grooming implements from the Hoxne hoard

Fashion in late antiquity[edit]

Roman clothing styles changed over time, though not as rapidly as contemporary fashions.[57] In the Dominate, clothing worn by both soldiers and government bureaucrats became highly decorated, with woven or embroidered strips, clavi, and circular roundels, orbiculi, added to tunics and cloaks. These decorative elements usually consisted of geometrical patterns and stylised plant motifs, but could include human or animal figures.[58] The use of silk also increased steadily and most courtiers of the later empire wore elaborate silk robes. The militarization of Roman society, and the waning of cultural life based on urban ideals, affected habits of dress: heavy military-style belts were worn by bureaucrats as well as soldiers, and early medieval kings and nobles abandoned the toga and dressed in the manner of Roman generals.[59]

-

late 5th century

Underwear and nudity[edit]

Erotic art shows women who are otherwise nude wearing a strapless bra (strophium). [60] The famous "bikini girls" who appear on a mosaic from xxxxx wear a strapless bra or bandeau and fitted briefs. They hold various kinds of apparatus, and may be exercising, or training for or performing dance routines that are perhaps to be compared to rhythmic gymnastics. Men's underwear xxxxxxxxxxx. In Roman art, laborers are often depicted in a loincloth.

Attitudes toward nudity and its depiction changed under the Christian Empire, and even erotes (Cupids) began to be portrayed clothed.[61] Nudity became a marker of "pagan" culture, and by the 5th century, female martyrs were sometimes depicted partially nude as victims of persecution.[62] Among the upper classes, modesty about the body did not preclude a greater showing off one's status, wealth, and xxxxxxx[63]

References[edit]

- ^ Mary Harlow, "Clothes Maketh the Man: Power Dressing and Elite Masculinity in the Later Roman World, in Gender in the Early Medieval World: East and West, 300–900 (Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 51.

- ^ Caroline Vout, "The Myth of the Toga: Understanding the History of Roman Dress," Greece & Rome 43.2 (1996), p. 218.

- ^ Vout, "The Myth of the Toga," p. 216; Margarete Bieber, "Roman Men in Greek Himation (Romani Palliati) a Contribution to the History of Copying," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 103.3 (1959), p. 412.

- ^ Vout, "The Myth of the Toga," pp. 204–220, especially pp. 206, 211; Bieber, "Roman Men in Greek Himation," 374–417; Guy P.R. Métraux, "Prudery and Chic in Late Antique Clothing," in Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture (University of Toronto Press, 2008), p. 286.

- ^ Mireille M. Lee, "Clothing," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 230.

- ^ Lynda L. Coon, Sacred Fictions: Holy Women and Hagiography in Late Antiquity (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997), p. 57.

- ^ Ulpian, Digest 34.2.23.2, as cited by Amy Richlin, "Not before Homosexuality: The Materiality of the cinaedus and the Roman Law against Love between Men," Journal of the History of Sexuality 3.4 (1993), p. 540.

- ^ The figure is variously interpreted as a daughter of the household looking out on the world, a household slave taking a break from her chores, or Methe, the mythological embodiment of drunkenness, after a 4th-century BC work by the Greek painter Pausias. The fragment would have appeared in the upper part of a painting covering the whole wall, executed in the Second Style; see "Wall Fragment with a Woman on a Balcony," The J. Paul Getty Museum collection note.

- ^ Lee, "Clothing," Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 231.

- ^ Lee, "Clothing," Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome p. 231.

- ^ Vout, "The Myth of the Toga," p. 216

- ^ Bieber, "Roman Men in Greek Himation," p. 412.

- ^ Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria 11.3.137–149; Bieber, "Roman Men in Greek Himation," p. 412; Coon, Sacred Fictions, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Bieber, "Roman Men in Greek Himation," p. 415.

- ^ Métraux, "Prudery and Chic in Late Antique Clothing," pp. 282–283.

- ^ Sebesta

- ^ Cleland, p. 194.

- ^ Liza Cleland, Greek and Roman Dress from A to Z p.194.

- ^ Cleland, p. 194; Claudian p. 219.CHECK

- ^ Cicero, In Pisonem 29.72, 30.73; Velleius Paterculus 1.12.3; Cleland, Greek and Roman Dress from A to Z, p. 194.

- ^ Tacitus Annals 16.27 and Histories 1.38; Cleland, Greek and Roman Dress from A to Z, p. 194.

- ^ Catharine Edwards, "Unspeakable Professions: Public Performance and Prostitution in Ancient Rome," in Roman Sexualities (Princeton University Press, 1997), p. 81; Lee, "Clothing," Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome p. 230.

- ^ XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX.

- ^ Harlow, "Clothes Maketh the Man," p. 51.

- ^ Candidati regni caelestis (Nicetas, a 4th-century bishop of Aquileia, Libellus ad virginem lapsam 5.19), candidatus Dei (Tertullian, Ad uxorem 2.7), candidatus exercitus martyrum, a "white-robed army of martyrs" in the Te Deum; Christopher Francese, Ancient Rome in So Many Words (Hippocrene Books, 2007), p. 121.

- ^ Francese, Ancient Rome in So Many Words, p. 121; Sergey Trostyanskiy, "Baptism," in The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity (Blackwell, 2011), p. 66; Anders Klostergaard Petersen, "Rituals of Purification, Rituals of Initiation," in Ablution, Initiation, and Baptism: Late Antiquity, Early Judaism, and Early Christianity (Walter de Gruyter, 2011), p. 13, citing the symbolism of Justin Martyr's account of baptism in his First Apology ("and though your sins be scarlet, I will make them white like wool").

- ^ A.H.M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 284–602: A Social, Economic, and Administrative Survey p. 1253; Hugh Elton, "Warfare and the Military," in The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine (Cambridge University Press, 2006, 2012), p. 336; James Allan Evans, The Emperor Justinian and the Byzantine Emperor (Greenwood Press, 2005), p. 147.

- ^ Lee, "Clothing," Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome p. 231.

- ^ A.H.M. Jones, "The Cloth Industry under the Roman Empire," Economic History Review 13.2 (1960), p. 184.

- ^ Tertullian, De Pallio 5.2; Bieber, "Roman Men in Greek Himation," pp. 399–411; Coon, Sacred Fictions, p. 58.

- ^ Bieber, "Roman Men in Greek Himation," p. 413, 415–416.

- ^ Vout?????

- ^ Vout, "The Myth of the Toga," p. 213.

- ^ xxxxxx

- ^ xxxxxxxxxxx

- ^ Vout, "The Myth of the Toga," p. 213.

- ^ Matthew B. Roller, Dining Posture in Ancient Rome: Bodies, Values, and Status (Princeton University Press, 2006), p. 34.

- ^ Lee, "Clothing," Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome p. 231.

- ^ Sebesta p. 47.

- ^ Jones, "The Cloth Industry under the Roman Empire," pp. 184–185.

- ^ Jones, "The Cloth Industry under the Roman Empire," p. 186.

- ^ Jones, "The Cloth Industry under the Roman Empire," p. 186.

- ^ Jones, "The Cloth Industry under the Roman Empire," p. 186.

- ^ Jones, "The Cloth Industry under the Roman Empire," p. 185.

- ^ Vout, "The Myth of the Toga," p. 212. The college of centonarii is an elusive topic in scholarship, since they are also widely attested as urban firefighters; see Jinyu Liu, Collegia Centonariorum: The Guilds of Textile Dealers in the Roman West (Brill, 2009). Liu sees them as "primarily tradesmen and/or manufacturers engaged in the production and distribution of low- or medium-quality woolen textiles and clothing, including felt and its products."

- ^ Elaine Fantham, "Covering the Head at Rome" Ritual and Gender," in Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture (University of Toronto Press, 2008), p. 168ff.

- ^ xxxxxxxxx

- ^ Lee, "Clothing," Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome p. 231.

- ^ Stout, "Jewelry as a Symbol of Status," p. 78.

- ^ Stout, "Jewelry as a Symbol of Status," p. 78.

- ^ Stout, "Jewelry as a Symbol of Status," p. 78.

- ^ Stout, "Jewelry as a Symbol of Status," pp. 77–78.

- ^ Stout, "Jewelry as a Symbol of Status," p. 77.

- ^ Piotr Grotowski, Arms and Armour of the Warrior Saints: Tradition and Innovation in Byzantine (Brill, 2009), p. 295.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Coon, Sacred Fictions, p. 58.

- ^ Lee, "Clothing," Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome p. 232.

- ^ Raffaele D'Amato, Roman Military Clothing (3) AD 400 to 640 (Osprey, 2005), pp. 7–9.

- ^ Chris Wickham, The Inheritance of Rome (Penguin Books Ltd., 2009), p. 106. ISBN 978-0-670-02098-0

- ^ Lee, "Clothing," in Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome p. 230.

- ^ Métraux, "Prudery and Chic in Late Antique Clothing," p. 280.

- ^ Métraux, "Prudery and Chic in Late Antique Clothing," pp. 281–282.

- ^ Métraux, "Prudery and Chic in Late Antique Clothing," pp. 286–287.

![Silver ring possibly to Toutatis[55]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8c/Silver_Tot_ring.jpg/57px-Silver_Tot_ring.jpg)