User:Cdjp1/sandbox/ww2w

Left communism[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Left communism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left wing of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices espoused by Marxist–Leninists and social democrats.[1] Left communists assert positions which they regard as more authentically Marxist than the views of Marxism–Leninism espoused by the Communist International after its Bolshevization by Joseph Stalin and during its second congress.[2][3][4]

In general, there are two currents of left communism, namely the Italian and Dutch–German left. The communist left in Italy was formed during World War I in organizations like the Italian Socialist Party and the Communist Party of Italy. The Italian left considers itself to be Leninist in nature, but denounces Marxism–Leninism as a form of bourgeois opportunism materialized in the Soviet Union under Stalin. The Italian left is currently embodied in organizations such as the Internationalist Communist Party and the International Communist Party. The Dutch–German left split from Vladimir Lenin prior to Stalin's rule and supports a firmly council communist and libertarian Marxist viewpoint as opposed to the Italian left which emphasised the need for an international revolutionary party.[5]

Left communism differs from most other forms of Marxism in believing that communists should not participate in bourgeois parliaments, and some argue against participating in conservative trade unions. However, many left communists split over their criticism of the Bolsheviks. Council communists criticised the Bolsheviks for elitist party functions and emphasised a more autonomous organisation of the working class, without political parties.

Although she was murdered in 1919 before left communism became a distinct tendency, Rosa Luxemburg has been heavily influential for most left communists, both politically and theoretically. Proponents of left communism have included Herman Gorter, Antonie Pannekoek, Otto Rühle, Karl Korsch, Amadeo Bordiga and Paul Mattick.[2] Other proponents of left communism have included Onorato Damen, Jacques Camatte, and Sylvia Pankhurst. Later prominent theorists are shared with other tendencies such as Antonio Negri, a founding theorist of the autonomist tendency.[6] Specific currents that can be labelled part of left communism include Bordigism, De Leonism, Luxemburgism, and communization.[7]

Early history and overview[edit]

Two major traditions can be observed within left communism, namely the Dutch–German current and the Italian current.[8] The political positions those traditions share are opposition to popular fronts, to many kinds of nationalism and national liberation movements and to parliamentarianism.

The historical origins of left communism come from World War I.[9] Most left communists are supportive of the October Revolution in Russia, but retain a critical view of its development. However, some in the Dutch–German current would in later years come to reject the idea that the revolution had a proletarian or socialist nature, arguing that it had simply carried out the tasks of the bourgeois revolution by creating a state capitalist system.[10]

Left communism first came into focus as a distinct movement around 1918. Its essential features were a stress on the need to build a communist party or workers' council entirely separate from the reformist and centrist elements who "betrayed the proletariat", opposition to all but the most restricted participation in elections and an emphasis on militancy. Apart from this, there was little in common between the two wings. Only the Italians accepted the need for electoral work at all for a very short period of time which they later vehemently opposed, attracting criticism from Vladimir Lenin in "Left-Wing" Communism: An Infantile Disorder.[11]

Russian left communism[edit]

Left Bolshevism emerged in 1907 as the Vpered group challenged Vladimir Lenin's perceived authoritarianism and parliamentarianism. The group included Alexander Bogdanov, Maxim Gorky, Anatoly Lunacharsky, Mikhail Pokrovsky, Grigory Aleksinsky, Stanislav Volski and Martyn Liadov. The Otzovists, or Recallists, advocated the recall of RSDLP representatives from the Third Duma. Bogdanov and his allies accused Lenin and his partisans of promoting liberal democracy through "parliamentarism at any price".[12]: 8

~Russia[edit]

In 1918, a faction emerged within the Russian Communist Party named the Left Communists which opposed the signing of the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty with Imperial Germany. The Left Communists wanted international proletarian revolution across the world. In the beginning, the leader of this faction was Nikolai Bukharin. They stood for a revolutionary war against the Central Powers; opposed the right of nations to self-determination (specifically in the case of Poland since there were many Poles in this communist group and they did not want a Polish capitalist state to be established); and they generally took a voluntarist stance regarding the possibilities for social revolution at that time.[citation needed] They began to publish the newspaper Kommunist.[13]

The Left Communists faded as the world revolutionary wave died down in militancy as Lenin had proved too strong a figure. They also lost Bukharin as a leading figure since his position became more right-wing until he eventually came to agree with Lenin. Being defeated in internal debates, they then dissolved.[citation needed] A few very small left communist groups surfaced within the RSFSR in the next few years, but later fell victim to repression by the state. In many ways, the positions of the Left Communists were inherited by the Workers' Opposition faction and Gavril Myasnikov's Workers Group of the Russian Communist Party and to some extent by the Decists.[citation needed]

In 1918, a faction known as the Left Communists (or the Left Bolsheviks) emerged within the Russian Communist Party. It opposed a separate peace treaty with the Central Powers of World War I, held radical views on economic and social policy (including cultural, educational, and family policy) and on military organization, and opposed national self-determination. Its members included Andrei Bubnov, Nikolai Bukharin, Alexandra Kollontai, Valerian Osinsky, Georgy Pyatakov, Yevgeni Preobrazhensky, Karl Radek, and Vladimir Smirnov. After the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed in March 1918, the Left Bolsheviks continued to criticize the "pragmatism" and "conservatism" of Lenin and his allies, urging immediate nationalization of industry, workers' control, and no compromise with capitalist forces.[14]

The faction largely died out by the end of 1918, as its leaders accepted that much of their program was unrealistic under the circumstances of the Russian Civil War and as the policies of War Communism satisfied their demands for a radical transformation of the economy. The Military Opposition and the Workers' Opposition inherited some characteristics and members of the Left Bolsheviks, as did Gavril Myasnikov's Workers Group of the Russian Communist Party during the debates on the New Economic Policy and the succession to Lenin. Most Left Bolsheviks were affiliated with the Left Opposition in the 1920s, and were expelled from the party in 1927 and later killed during Joseph Stalin's Great Purge.[14]

Italian left communism until 1926[edit]

The Italian left communists were named left communists at a later stage in their development, but when the Communist Party of Italy (PCd'I) was founded its members actually represented the majority of communists in that country. This was a result of the Abstentionist Communist Faction of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) being in advance of other sections of the PSI in their realisation that a separate communist party had to be formed which did not include reformists. This gave them a great advantage over the sections of the PSI who looked to figures such as Giacinto Menotti Serrati and Antonio Gramsci for leadership. It was a consequence of the revolutionary impatience common at a time when revolution, in the narrow sense of an insurrectionary attempt at the seizure of power, was expected to develop in the very near future.

Under the leadership of Amadeo Bordiga, the left was to control the PCd'I until the Lyons Congress of 1926. In this period, the militants of the PCd'I would find themselves isolated from reformist workers and from other anti-fascist militants. At one stage, this isolation was deepened when communist militants were instructed to leave defence organisations that were not totally controlled by the party. These sectarian tactics produced concern in the leadership of the Communist International and led to a developing opposition within the PCd'I itself. Eventually, these two factors led to the displacement of Bordiga from his position as first secretary and his replacement by Gramsci. By then, Bordiga was in a fascist jail and was to remain outside organised politics until 1952. The development of the Left Communist Faction was not the development of the Bordigist current (as it is often portrayed).

The year 1925 was a turning point for the Italian left as it was the year that the so-called Bolshevisation took place in the sections of the Communist International. This plan was designed to eliminate all social democratic deviations from the Communist International and develop them on Bolshevik lines or at least along the lines of what Grigory Zinoviev, the secretary of the Communist International, considered Bolshevik lines. In practice, this meant top-down bureaucratic structures in which the members were controlled by a leadership approved of by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI). In Italy, this meant that the leadership which had formerly been in the hands of Bordiga was given to a body that came into being when the Serrati-Maffi minority of the PSI joined the PCd'I, although Bordiga's group were in a majority. The new leadership was supported by Bordiga, who accepted the will of the Communist International as a centralist.

Nevertheless, Bordiga fought the ECCI from within only to have an article of his which was favourable to Leon Trotsky's positions on the disputed Russian questions suppressed. Meanwhile, sections of the left motivated by Onorato Damen formed the Entente Committee. This committee was ordered to dissolve itself by the incoming leadership led now by Gramsci, who only then opposed Bordiga's positions which had gained prestige after a successful recruitment campaign. With the party Congress of 1926 held in Lyons, crowned by Gramsci's famous Lyons Theses, the left majority was now defeated and on course to becoming a minority within the party. With the victory of fascism in Italy, Bordiga was jailed. When Bordiga opposed a vote against Trotsky in the prison PCd'I group, he was expelled from the party in 1930. He took a stance of non-involvement in politics for many years after this. The victory of Italian fascism also meant that the Italian left would enter into a new chapter in its development, but this time in exile.

Dutch–German left communism until 1933[edit]

Left communism emerged in both countries together and was always very closely connected. Among the leading theoreticians of the more powerful German movement were Antonie Pannekoek and Herman Gorter and German activists found refuge in the Netherlands after the Nazis came to power in 1933. The critique of social democratic reformism can be traced back before World War I since in the Netherlands a revolutionary wing of social democracy had broken from the reformist party even before the war and had built links with German activists. By 1915, the Antinational Socialist Party was founded by Franz Pfemfert and was linked to Die Aktion.[15] After the beginning of the German Revolution in 1918, a leftist mood could be found among sections of the communist parties of both countries. In Germany, this led directly to the foundation of the Communist Workers Party of Germany (KAPD) after its leading figures were expelled from the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) by Paul Levi. This development was mirrored in the Netherlands and on a smaller scale in Bulgaria, where the left communist movement was to mimic that of Germany.

When it was founded, the KAPD included some tens of thousands of revolutionaries. However, it had broken up and practically dissolved within a few years. This was because it was founded on the basis of revolutionary optimism and a purism that rejected what became known as frontism. Frontism entailed working in the same organisations as reformist workers. Such work was seen by the KAPD as unhelpful at a time when the revolution was thought to be an imminent event and not merely a goal to be aimed at. This led the members of the KAPD to reject working in the traditional trade unions in favour of forming their own revolutionary unions. These unionen, so called to distinguish them from the official trade unions, had 80,000 members in 1920 and peaked in 1921 with 200,000 members, after which they declined rapidly. They were also organisationally divided from the beginning, with those unionen linked to the KAPD forming the AAU-D and those in Saxony around Otto Rühle who opposed the conception of a party in favour of a unitary class organisation being organised as the AAU-E.

The KAPD was unable to reach even its founding congress prior to suffering its first split when the so-called National Bolshevik tendency around Fritz Wolffheim and Heinrich Laufenberg appeared (this tendency has no connection with modern political tendencies in Russia which use the same name). More seriously, the KAPD lost most of its support very rapidly as it failed to develop lasting structures. This also contributed to internecine quarrels and the party actually split into two competing tendencies known as the Essen and Berlin tendencies to the historians of the left. The recently established Communist Workers International (KAI) split on exactly the same lines as did the tiny Communist Workers Party of Bulgaria. The only other affiliates of the KAI were the Communist Workers Party of Britain led by Sylvia Pankhurst, the Communist Workers Party of the Netherlands (KAPN) in the Netherlands and a group in Russia. The AAU-D split on the same lines and it rapidly ceased to exist as a real tendency within the factories.

Left communism and the Communist International[edit]

Left communists generally supported the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917 and entertained enormous hopes in the founding of the Communist International, or Comintern. In fact, they controlled the first body formed by the Comintern to coordinate its activities in Western Europe, the Amsterdam Bureau. However, this was little more than a very brief interlude and the Amsterdam Bureau never functioned as a leadership body for Western Europe as was originally intended. The Vienna Bureau of the Comintern may also be classified as left communist, but its personnel were not to evolve into either of the two historic currents that made up left communism. Rather, the Vienna Bureau adopted the ultra-left ideas of the earliest period in the history of the Comintern.

Left communists supported the Russian Revolution, but did not accept the methods of the Bolsheviks. Many of the Dutch–German tradition adopted Rosa Luxemburg's criticism as outlined in her posthumously published essay entitled The Russian Revolution. In this essay, she rejected the Bolshevik position on distribution of land to the peasantry and their espousal of the right of nations to self-determination which she rejected as historically outmoded. The Italian left communists did not at the time accept any of these criticisms and both currents would evolve.

To a considerable degree, Lenin's well known polemic Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder[11] is an attack on the ideas of the emerging left communist currents. His main aim was to polemicise with currents moving towards pure revolutionary tactics by showing them that they could remain based on firmly revolutionary principles while utilising a variety of tactics. Therefore, Lenin defended the use of parliamentarism and working within the official trade unions.

As the Kronstadt rebellion occurred at a time when the debate on tactics was still raging within the Comintern, it has been wrongly seen as being left communist by some commentators. In fact, the left communist currents had no connection with the rebellion, although they did rally to its support when they learned of it. In later years, the German–Dutch tradition in particular would come to see the suppression of the revolt as the historic turning point in the evolution of the Russian state after October 1917.

1939–1945[edit]

Many small currents to the left of the mass communist parties collapsed at the beginning of World War II and the left communists were initially silent too. Despite having foreseen the war more clearly than some other factions, when it began they were overwhelmed. Many were persecuted by either German Nazism or Italian fascism. Leading militants of the communist left such as Mitchell, who was Jewish, were to die in the Buchenwald concentration camp.

Meanwhile, the final council communist groups in Germany had disappeared in the maelstrom and the International Communist Group (GIK) in the Netherlands was moribund. The former centrist group led by Henk Sneevliet (the Revolutionary Socialist Workers Party, RSAP) transformed itself into the Marx–Lenin–Luxemburg Front. In April 1942, its leadership was arrested by the Gestapo and killed. The remaining activists then split into two camps as some turned to Trotskyism forming the Committee of Revolutionary Marxists (CRM) while the majority formed the CommunistenBond-Spartacus. The latter group turned to council communism and was joined by most members of the GIK.

In 1941, the Italian fraction was reorganised in France and along with the new French Nucleus of the Communist Left came into conflict with the ideas which the fraction had propagated from 1936, namely of the social disappearance of the proletariat and localised wars and so on. These ideas continued to be defended by Vercesi in Brussels. Gradually, the left fractions adopted positions drawn from German left communism. They abandoned the conception that the Russian state remained in some way proletarian and also dropped Vercesi's conception of localised wars in favour of ideas on imperialism inspired by Rosa Luxemburg. Vercesi's participation in a Red Cross committee was also fiercely contested.

The strike at FIAT in October 1942 had a huge impact on the Italian fraction, which was deepened by the fall of Mussolini's regime in July 1943. The Italian fraction now saw a pre-revolutionary situation opening in Italy and prepared to participate in the coming revolution. In 1943 the Internationalist Communist Party was founded by Onorato Damen and Luciano Stefanini, amongst others. By 1945 the party had 5,000 members all over Italy with some supporters in France, Belgium and the US.[16] It published a Manifesto of the Communist Left to the European Proletariat, which called upon workers to put class war before national war.[17]

In France, revived by Marco in Marseilles, the Italian fraction now worked closely with the new French fraction, which was formally founded in Paris in December 1944. However, in May 1945 the Italian fraction, many of whose members had already returned to Italy, voted to dissolve itself so that its militants could integrate themselves as individuals into the Internationalist Communist Party. The conference at which this decision was made also refused to recognise the French fraction and expelled Marco from their group.

This led to a split in the French fraction and the formation of the Gauche Communiste de France (GCF) by the French fraction led by Marco. The history of the GCF belongs to the post-war period. Meanwhile, the former members of the French fraction who sympathised with Vercesi and the Internationalist Communist Party formed a new French fraction which published the journal L'Etincelle and was joined at the end of 1945 by the old minority of the fraction who had joined L'Union Communiste in the 1930s.

One other development during the war years merits mention at this point. A small grouping of German and Austrian militants came close to left communist positions in these years. Best known as the Revolutionary Communist Organisation, these young militants were exiles from Nazism living in France at the start of World War II and were members of the Trotskyist movement but they had opposed the formation of the Fourth International in 1938 on the grounds that it was premature. They were refused full delegates' credentials and only admitted to the founding conference of the Youth International on the following day. They then joined Hugo Oehler's International Contact Commission for the Fourth (Communist) International and in 1939 were publishing Der Marxist in Antwerp.

With the beginning of the war, they took the name Revolutionary Communists of Germany (RKD) and came to define Russia as state capitalist in agreement with Ante Ciliga's book The Russian Enigma. At this point, they adopted a revolutionary defeatist position on the war and condemned Trotskyism for its critical defence of Russia (which was seen by Trotskyists as a degenerated workers' state). After the fall of France, they renewed contact with militants in the Trotskyist milieu in Southern France and recruited some of them into the Communistes Revolutionnaires (CR) in 1942. This group became known as Fraternisation Proletarienne in 1943 and then L'Organisation Communiste Revolutionnaire in 1944. The CR and RKD were autonomous and clandestine, but worked closely together with shared politics. As the war ran its course, they evolved in a councilist direction while also identifying more and more with Luxemburg's work. They also worked with the French Fraction of the Communist Left and seem to have disintegrated at the end of the war. This disintegration was sped no doubt by the capture of leading militant Karl Fischer, who was sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp where he was to participate in writing the Declaration of the Internationalist Communists of Buchenwald when the camp was liberated.

1952–1968[edit]

The year 1952 signalled the end of mass influence on the part of Italian left communism as its sole remaining representative, the Internationalist Communist Party, split in two sections: the group led by Bordiga took the name International Communist Party, while the group around Damen retained the name Internationalist Communist Party. The Gauche Communiste de France (GCF) dissolved in the same year.[citation needed] Left communists entered a period of almost constant decline from this point onwards, although they were somewhat rejuvenated by the events of 1968.[citation needed]

Examples of left communism ideological currents existed in China during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (GPCR). For example, the Hunan rebel group the Shengwulian argued for "smashing" the existing state apparatus and establishing a "People's Commune of China" based on the democratic ideals of the Paris Commune.[18]

Since 1968[edit]

The uprisings of May 1968 led to a large resurgence of interest in left communist ideas in France where various groups were formed and published journals regularly until the late 1980s when the interest started to fade.[19] A tendency called communization was invented in the early 1970s by French left communists, synthesizing different currents of left communism. It remains influential in libertarian marxist and left communist circles today.[20] Outside of France, various small left communist groups emerged, predominantly in the leading capitalist countries.[21][22][23][24] In the late 1970s and early 1980s the Internationalist Communist Party initiated a series of conferences of the communist left to engage those new elements, also attended by the International Communist Current.[25] As a result of these, in 1983 the International Bureau for the Revolutionary Party (later renamed as the Internationalist Communist Tendency) was established by the Internationalist Communist Party and the British Communist Workers Organisation.[26]

Prominent post-1968 proponents of left communism have included Paul Mattick and Maximilien Rubel. Prominent left communist groups existing today include the International Communist Party, the International Communist Current and the Internationalist Communist Tendency.[27] In addition to the left communist groups in the direct lineage of the Italian and Dutch traditions, a number of groups with similar positions have flourished since 1968, such as the workerist and autonomist movements in Italy; Kolinko, Kurasje, Wildcat;[28] Subversion and Aufheben in England; Théorie Communiste, Echanges et Mouvements and Démocratie Communiste in France; TPTG[29] and Blaumachen[30] in Greece; Kamunist Kranti in India; and Collective Action Notes and Loren Goldner in the United States.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Bordiga, Amadeo (1926). The Communist Left in the Third International. Retrieved 23 September 2021 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Gorter, Hermann; Pannekoek, Antonie; Pankhurst, Sylvia; Rühle, Otto (2007). Non-Leninist Marxism: Writings on the Workers Councils. St. Petersburg, Florida: Red and Black Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9791813-6-8.

- ^ Bordiga, Amadeo. Dialogue with Stalin. Retrieved 15 May 2019 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Kowalski, Ronald I. (1991). The Bolshevik Party in Conflict: The Left Communist Opposition of 1918. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 2. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-10367-6. ISBN 978-1-349-10369-0.

- ^ Bourrinet, Philippe. "The Bordigist Current (1919-1999)". Archived from the original on 20 January 2022.

- ^ Negri, Antonio (1991). Marx beyond Marx: Lessons on the Grundrisse. Translated by Ryan, Michael. New York: Autonomedia.

- ^ Piccone, Paul (1983). Italian Marxism. University of California Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-520-04798-3.

- ^ Smeaton, A. (1 August 2003). "Background on the Italian Communist Left, Bordiga and Bordigism". Internationalist Communist. No. 22. Retrieved 17 October 2013 – via Leftcom.

- ^ Luxemburg, Rosa (1915). The Junius Pamphlet. Retrieved 23 September 2021 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Fox, Michael S. (Spring 1991). "Ante Ciliga, Trotskii, and State Capitalism: Theory, Tactics, and Reevaluation during the Purge Era, 1935–1939" (PDF). Slavic Review. 50 (1). Cambridge University Press: 127–143. doi:10.2307/2500604. JSTOR 2500604. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 26 June 2020 – via GeoCities.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Lenin, V.I. Left-Wing Communism: an Infantile Disorder. Retrieved 17 October 2013 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Sochor, Z. A. (28 March 1988). Revolution and Culture: The Bogdanov-Lenin Controversy. Cornell University Press. pp. 4–8. ISBN 9780801420887.

- ^ "Glossary of Periodicals: Ko". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ a b Smele, Jonathan D. (2015). Historical Dictionary of the Russian Civil Wars, 1916–1926. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 667–668. ISBN 978-1-4422-5280-6.

- ^ Taylor, Seth (1990). Left-Wing Nietzscheans: The Politics of German Expressionism 1910-1920. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 220.

- ^ "The Italian Communist Left - A Brief Internationalist History". Revolutionary Perspectives. Communist Workers' Organisation. 2009.

- ^ "The 1944 Manifesto of the Internationalist Communist Left". Revolutionary Perspectives. Communist Workers' Organisation. 2016.

- ^ Meisner, Maurice J. (1986). Mao's China and after: a history of the People's Republic (A revised and expanded edition of Mao's China ed.). New York. pp. 343–344. ISBN 0-02-920870-X. OCLC 13270932.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Archive of French left communist journals after 1952". Archives Autonomies. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "On Communisation and Its Theorists". Endnotes. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "May 68: the student movement in France and the world". Internationalism. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ Lassou (May 2012). "Contribution to a history of the workers' movement in Africa (v): May 1968 in Senegal". Internationalism. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ Ken (23 March 2008). "1968 in Japan: the student movement and workers' struggles". Internationalism. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ "1968 in Germany (Part 1): Behind the protest movement – the search for a new society". Internationalism. 26 May 2008. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ Bourrinet, Philippe (2000). The "Bordigist" Current (1912-1952). pp. 332–333.

- ^ "About Us". Internationalist Communist Tendency.

- ^ Bourseiller, Christophe (2003). Histoire générale de l'Ultra-Gauche [General history of the Ultra-Left] (in French). Paris: Editions Denoël. ISBN 2207251632.

- ^ "Wildcat". Wildcat-www.de. 21 September 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ "Ta paidiá tis galarías" Τα παιδιά της γαλαρίας [The children of the gallery] (in Greek). Tapaidiatisgalarias.org. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ "Blaumachen – journal". Blaumachen.gr. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

Further reading[edit]

- Non-Leninist Marxism: Writings on the Workers Councils (2007) (includes texts by Herman Gorter, Antonie Pannekoek, Sylvia Pankhurst and Otto Rühle). St. Petersburg, Florida: Red and Black Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9791813-6-8.

- Alexandra Kollontai: Selected Writing. Allison & Busby, 1984.

- Pannekoek, Anton. Workers Councils. AK Press, 2003. Introduction by Noam Chomsky

- The International Communist Current, itself a left communist grouping, has produced a series of studies of what it views as its own antecedents. In particular, the book on the Dutch–German current, which is by Philippe Bourrinet (who later left the ICC), contains an exhaustive bibliography.

- The Italian Communist Left 1926–1945 (ISBN 1897980132).

- The Dutch-German Communist Left (ISBN 1899438378).

- The Russian Communist Left, 1918–1930 (ISBN 1897980108).

- The British Communist Left, 1914–1945 (ISBN 1897980116).

- Also of interest is volume 5 number 4 of Spring 1995 of the journal Revolutionary History. "Through Fascism, War and Revolution: Trotskyism and Left Communism in Italy".

- In addition, there is a good deal of material published on the Internet in various languages. A useful starting point is the Left Communism collection published on the Marxists Internet Archive.

Karl Marx[edit]

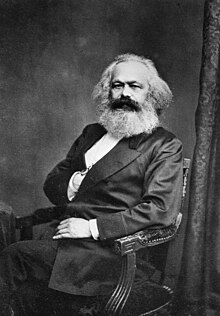

Karl Marx | |

|---|---|

Photograph by John Mayall, 1875 | |

| Born | Karl Heinrich Marx 5 May 1818 |

| Died | 14 March 1883 (aged 64) London, England |

| Burial place | Tomb of Karl Marx, Highgate Cemetery |

| Nationality | |

| Education | |

| Spouse | |

| Children | At least 7,[2] including Jenny, Laura and Eleanor |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

Philosophy career | |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Thesis | The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature (1841) |

| Doctoral advisor | Bruno Bauer |

Main interests |

|

Notable ideas |

|

| Signature | |

Karl Heinrich Marx FRSA[3] (German: [maʁks]; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 pamphlet The Communist Manifesto and the four-volume Das Kapital (1867–1883). Marx's political and philosophical thought had enormous influence on subsequent intellectual, economic, and political history. His name has been used as an adjective, a noun, and a school of social theory.

Born in Trier, Germany, Marx studied law and philosophy at the universities of Bonn and Berlin. He married German theatre critic and political activist Jenny von Westphalen in 1843. Due to his political publications, Marx became stateless and lived in exile with his wife and children in London for decades, where he continued to develop his thought in collaboration with German philosopher Friedrich Engels and publish his writings, researching in the British Museum Reading Room.

Marx's critical theories about society, economics, and politics, collectively understood as Marxism, hold that human societies develop through class conflict. In the capitalist mode of production, this manifests itself in the conflict between the ruling classes (known as the bourgeoisie) that control the means of production and the working classes (known as the proletariat) that enable these means by selling their labour-power in return for wages.[4] Employing a critical approach known as historical materialism, Marx predicted that capitalism produced internal tensions like previous socioeconomic systems and that these tensions would lead to its self-destruction and replacement by a new system known as the socialist mode of production. For Marx, class antagonisms under capitalism—owing in part to its instability and crisis-prone nature—would eventuate the working class's development of class consciousness, leading to their conquest of political power and eventually the establishment of a classless, communist society constituted by a free association of producers.[5] Marx actively pressed for its implementation, arguing that the working class should carry out organised proletarian revolutionary action to topple capitalism and bring about socio-economic emancipation.[6]

Marx has been described as one of the most influential figures in human history, and his work has been both lauded and criticised.[7] His work in economics laid the basis for some current theories about labour and its relation to capital.[8][9][10] Many intellectuals, labour unions, artists, and political parties worldwide have been influenced by Marx's work, often modifying or adapting his ideas. Marx is typically cited as one of the principal architects of modern social science.[11][12]

Biography[edit]

Childhood and early education: 1818–1836[edit]

Karl Heinrich Marx was born on 5 May 1818 to Heinrich Marx (1777–1838) and Henriette Pressburg (1788–1863). He was born at Brückengasse 664 in Trier, an ancient city then part of the Kingdom of Prussia's Province of the Lower Rhine.[13] Marx's family was originally non-religious Jewish, but had converted formally to Christianity before his birth. His maternal grandfather was a Dutch rabbi, while his paternal line had supplied Trier's rabbis since 1723, a role taken by his grandfather Meier Halevi Marx.[14] His father, as a child known as Herschel, was the first in the line to receive a secular education. He became a lawyer with a comfortably upper middle class income and the family owned a number of Moselle vineyards, in addition to his income as an attorney. Prior to his son's birth and after the abrogation of Jewish emancipation in the Rhineland,[15] Herschel converted from Judaism to join the state Evangelical Church of Prussia, taking on the German forename Heinrich over the Yiddish Herschel.[16]

Largely non-religious, Heinrich was a man of the Enlightenment, interested in the ideas of the philosophers Immanuel Kant and Voltaire. A classical liberal, he took part in agitation for a constitution and reforms in Prussia, which was then an absolute monarchy.[19] In 1815, Heinrich Marx began working as an attorney and in 1819 moved his family to a ten-room property near the Porta Nigra.[20] His wife, Henriette Pressburg, was a Dutch Jew from a prosperous business family that later founded the company Philips Electronics. Her sister Sophie Pressburg (1797–1854) married Lion Philips (1794–1866) and was the grandmother of both Gerard and Anton Philips and great-grandmother to Frits Philips. Lion Philips was a wealthy Dutch tobacco manufacturer and industrialist, upon whom Karl and Jenny Marx would later often come to rely for loans while they were exiled in London.[21]

Little is known of Marx's childhood.[22] The third of nine children, he became the eldest son when his brother Moritz died in 1819.[23] Marx and his surviving siblings, Sophie, Hermann, Henriette, Louise, Emilie, and Caroline, were baptised into the Lutheran Church in August 1824, and their mother in November 1825.[24] Marx was privately educated by his father until 1830 when he entered Trier High School (Gymnasium zu Trier), whose headmaster, Hugo Wyttenbach, was a friend of his father. By employing many liberal humanists as teachers, Wyttenbach incurred the anger of the local conservative government. Subsequently, police raided the school in 1832 and discovered that literature espousing political liberalism was being distributed among the students. Considering the distribution of such material a seditious act, the authorities instituted reforms and replaced several staff during Marx's attendance.[25]

In October 1835 at the age of 16, Marx travelled to the University of Bonn wishing to study philosophy and literature, but his father insisted on law as a more practical field.[26] Due to a condition referred to as a "weak chest",[27] Marx was excused from military duty when he turned 18. While at the University at Bonn, Marx joined the Poets' Club, a group containing political radicals that were monitored by the police.[28] Marx also joined the Trier Tavern Club drinking society (German: Landsmannschaft der Treveraner) where many ideas were discussed and at one point he served as the club's co-president.[29][30] Additionally, Marx was involved in certain disputes, some of which became serious: in August 1836 he took part in a duel with a member of the university's Borussian Korps.[31] Although his grades in the first term were good, they soon deteriorated, leading his father to force a transfer to the more serious and academic University of Berlin.[32]

Hegelianism and early journalism: 1836–1843[edit]

|

| Hegelianism |

|---|

| Forerunners |

| Principal works |

| Schools |

| Related topics |

| Related categories |

Spending summer and autumn 1836 in Trier, Marx became more serious about his studies and his life. He became engaged to Jenny von Westphalen, an educated member of the petty nobility who had known Marx since childhood. As she had broken off her engagement with a young aristocrat to be with Marx, their relationship was socially controversial owing to the differences between their religious and class origins, but Marx befriended her father Ludwig von Westphalen (a liberal aristocrat) and later dedicated his doctoral thesis to him.[33] Seven years after their engagement, on 19 June 1843, they married in a Protestant church in Kreuznach.[34]

In October 1836, Marx arrived in Berlin, matriculating in the university's faculty of law and renting a room in the Mittelstrasse.[35] During the first term, Marx attended lectures of Eduard Gans (who represented the progressive Hegelian standpoint, elaborated on rational development in history by emphasising particularly its libertarian aspects, and the importance of social question) and of Karl von Savigny (who represented the Historical School of Law).[36] Although studying law, he was fascinated by philosophy and looked for a way to combine the two, believing that "without philosophy nothing could be accomplished".[37] Marx became interested in the recently deceased German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, whose ideas were then widely debated among European philosophical circles.[38] During a convalescence in Stralau, he joined the Doctor's Club (Doktorklub), a student group which discussed Hegelian ideas, and through them became involved with a group of radical thinkers known as the Young Hegelians in 1837. They gathered around Ludwig Feuerbach and Bruno Bauer, with Marx developing a particularly close friendship with Adolf Rutenberg. Like Marx, the Young Hegelians were critical of Hegel's metaphysical assumptions, but adopted his dialectical method to criticise established society, politics and religion from a left-wing perspective.[39] Marx's father died in May 1838, resulting in a diminished income for the family.[40] Marx had been emotionally close to his father and treasured his memory after his death.[41]

By 1837, Marx was writing both fiction and non-fiction, having completed a short novel, Scorpion and Felix; a drama, Oulanem; as well as a number of love poems dedicated to Jenny von Westphalen. None of this early work was published during his lifetime.[42] The love poems were published posthumously in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 1.[43] Marx soon abandoned fiction for other pursuits, including the study of both English and Italian, art history and the translation of Latin classics.[44] He began co-operating with Bruno Bauer on editing Hegel's Philosophy of Religion in 1840. Marx was also engaged in writing his doctoral thesis, The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature,[45] which he completed in 1841. It was described as "a daring and original piece of work in which Marx set out to show that theology must yield to the superior wisdom of philosophy".[46] The essay was controversial, particularly among the conservative professors at the University of Berlin. Marx decided instead to submit his thesis to the more liberal University of Jena, whose faculty awarded him his Ph.D. in April 1841.[1][47] As Marx and Bauer were both atheists, in March 1841 they began plans for a journal entitled Archiv des Atheismus (Atheistic Archives), but it never came to fruition. In July, Marx and Bauer took a trip to Bonn from Berlin. There they scandalised their class by getting drunk, laughing in church and galloping through the streets on donkeys.[48]

Marx was considering an academic career, but this path was barred by the government's growing opposition to classical liberalism and the Young Hegelians.[49] Marx moved to Cologne in 1842, where he became a journalist, writing for the radical newspaper Rheinische Zeitung (Rhineland News), expressing his early views on socialism and his developing interest in economics. Marx criticised right-wing European governments as well as figures in the liberal and socialist movements, whom he thought ineffective or counter-productive.[50] The newspaper attracted the attention of the Prussian government censors, who checked every issue for seditious material before printing, which Marx lamented: "Our newspaper has to be presented to the police to be sniffed at, and if the police nose smells anything un-Christian or un-Prussian, the newspaper is not allowed to appear".[51] After the Rheinische Zeitung published an article strongly criticising the Russian monarchy, Tsar Nicholas I requested it be banned and Prussia's government complied in 1843.[52]

Paris: 1843–1845[edit]

In 1843, Marx became co-editor of a new, radical left-wing Parisian newspaper, the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher (German-French Annals), then being set up by the German activist Arnold Ruge to bring together German and French radicals.[53] Therefore Marx and his wife moved to Paris in October 1843. Initially living with Ruge and his wife communally at 23 Rue Vaneau, they found the living conditions difficult, so moved out following the birth of their daughter Jenny in 1844.[54] Although intended to attract writers from both France and the German states, the Jahrbücher was dominated by the latter and the only non-German writer was the exiled Russian anarchist collectivist Mikhail Bakunin.[55] Marx contributed two essays to the paper, "Introduction to a Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right"[56] and "On the Jewish Question",[57] the latter introducing his belief that the proletariat were a revolutionary force and marking his embrace of communism.[58] Only one issue was published, but it was relatively successful, largely owing to the inclusion of Heinrich Heine's satirical odes on King Ludwig of Bavaria, leading the German states to ban it and seize imported copies (Ruge nevertheless refused to fund the publication of further issues and his friendship with Marx broke down).[59] After the paper's collapse, Marx began writing for the only uncensored German-language radical newspaper left, Vorwärts! (Forward!). Based in Paris, the paper was connected to the League of the Just, a utopian socialist secret society of workers and artisans. Marx attended some of their meetings but did not join.[60] In Vorwärts!, Marx refined his views on socialism based upon Hegelian and Feuerbachian ideas of dialectical materialism, at the same time criticising liberals and other socialists operating in Europe.[61]

On 28 August 1844, Marx met the German socialist Friedrich Engels at the Café de la Régence, beginning a lifelong friendship.[62] Engels showed Marx his recently published The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844,[63][64] convincing Marx that the working class would be the agent and instrument of the final revolution in history.[65][66] Soon, Marx and Engels were collaborating on a criticism of the philosophical ideas of Marx's former friend, Bruno Bauer. This work was published in 1845 as The Holy Family.[67][68] Although critical of Bauer, Marx was increasingly influenced by the ideas of the Young Hegelians Max Stirner and Ludwig Feuerbach, but eventually Marx and Engels abandoned Feuerbachian materialism as well.[69]

During the time that he lived at 38 Rue Vaneau in Paris (from October 1843 until January 1845),[70] Marx engaged in an intensive study of political economy (Adam Smith, David Ricardo, James Mill, etc.),[71] the French socialists (especially Claude Henri St. Simon and Charles Fourier)[72] and the history of France.[73] The study of, and critique of political economy is a project that Marx would pursue for the rest of his life[74] and would result in his major economic work—the three-volume series called Das Kapital.[75] Marxism is based in large part on three influences: Hegel's dialectics, French utopian socialism and British political economy. Together with his earlier study of Hegel's dialectics, the studying that Marx did during this time in Paris meant that all major components of "Marxism" were in place by the autumn of 1844.[76] Marx was constantly being pulled away from his critique of political economy—not only by the usual daily demands of the time, but additionally by editing a radical newspaper and later by organising and directing the efforts of a political party during years of potentially revolutionary popular uprisings of the citizenry. Still, Marx was always drawn back to his studies where he sought "to understand the inner workings of capitalism".[73]

An outline of "Marxism" had definitely formed in the mind of Karl Marx by late 1844. Indeed, many features of the Marxist view of the world had been worked out in great detail, but Marx needed to write down all of the details of his world view to further clarify the new critique of political economy in his own mind.[77] Accordingly, Marx wrote The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts.[78] These manuscripts covered numerous topics, detailing Marx's concept of alienated labour.[79] By the spring of 1845, his continued study of political economy, capital and capitalism had led Marx to the belief that the new critique of political economy he was espousing—that of scientific socialism—needed to be built on the base of a thoroughly developed materialistic view of the world.[80]

The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 had been written between April and August 1844, but soon Marx recognised that the Manuscripts had been influenced by some inconsistent ideas of Ludwig Feuerbach. Accordingly, Marx recognised the need to break with Feuerbach's philosophy in favour of historical materialism, thus a year later (in April 1845) after moving from Paris to Brussels, Marx wrote his eleven "Theses on Feuerbach".[81] The "Theses on Feuerbach" are best known for Thesis 11, which states that "philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways, the point is to change it".[79][82] This work contains Marx's criticism of materialism (for being contemplative), idealism (for reducing practice to theory), and, overall, philosophy (for putting abstract reality above the physical world).[79] It thus introduced the first glimpse at Marx's historical materialism, an argument that the world is changed not by ideas but by actual, physical, material activity and practice.[79][83] In 1845, after receiving a request from the Prussian king, the French government shut down Vorwärts!, with the interior minister, François Guizot, expelling Marx from France.[84]

Brussels: 1845–1848[edit]

Unable either to stay in France or to move to Germany, Marx decided to emigrate to Brussels in Belgium in February 1845. However, to stay in Belgium he had to pledge not to publish anything on the subject of contemporary politics.[84] In Brussels, Marx associated with other exiled socialists from across Europe, including Moses Hess, Karl Heinzen and Joseph Weydemeyer. In April 1845, Engels moved from Barmen in Germany to Brussels to join Marx and the growing cadre of members of the League of the Just now seeking home in Brussels.[84][85] Later, Mary Burns, Engels' long-time companion, left Manchester, England to join Engels in Brussels.[86]

In mid-July 1845, Marx and Engels left Brussels for England to visit the leaders of the Chartists, a working-class movement in Britain. This was Marx's first trip to England and Engels was an ideal guide for the trip. Engels had already spent two years living in Manchester from November 1842[87] to August 1844.[88] Not only did Engels already know the English language,[89] he had also developed a close relationship with many Chartist leaders.[89] Indeed, Engels was serving as a reporter for many Chartist and socialist English newspapers.[89] Marx used the trip as an opportunity to examine the economic resources available for study in various libraries in London and Manchester.[90]

In collaboration with Engels, Marx also set about writing a book which is often seen as his best treatment of the concept of historical materialism, The German Ideology.[91] In this work, Marx broke with Ludwig Feuerbach, Bruno Bauer, Max Stirner and the rest of the Young Hegelians, while he also broke with Karl Grün and other "true socialists" whose philosophies were still based in part on "idealism". In German Ideology, Marx and Engels finally completed their philosophy, which was based solely on materialism as the sole motor force in history.[92] German Ideology is written in a humorously satirical form, but even this satirical form did not save the work from censorship. Like so many other early writings of his, German Ideology would not be published in Marx's lifetime and would be published only in 1932.[79][93][94]

After completing German Ideology, Marx turned to a work that was intended to clarify his own position regarding "the theory and tactics" of a truly "revolutionary proletarian movement" operating from the standpoint of a truly "scientific materialist" philosophy.[95] This work was intended to draw a distinction between the utopian socialists and Marx's own scientific socialist philosophy. Whereas the utopians believed that people must be persuaded one person at a time to join the socialist movement, the way a person must be persuaded to adopt any different belief, Marx knew that people would tend, on most occasions, to act in accordance with their own economic interests, thus appealing to an entire class (the working class in this case) with a broad appeal to the class's best material interest would be the best way to mobilise the broad mass of that class to make a revolution and change society. This was the intent of the new book that Marx was planning, but to get the manuscript past the government censors he called the book The Poverty of Philosophy (1847)[96] and offered it as a response to the "petty-bourgeois philosophy" of the French anarchist socialist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon as expressed in his book The Philosophy of Poverty (1840).[97]

These books laid the foundation for Marx and Engels's most famous work, a political pamphlet that has since come to be commonly known as The Communist Manifesto. While residing in Brussels in 1846, Marx continued his association with the secret radical organisation League of the Just.[98] As noted above, Marx thought the League to be just the sort of radical organisation that was needed to spur the working class of Europe toward the mass movement that would bring about a working-class revolution.[99] However, to organise the working class into a mass movement the League had to cease its "secret" or "underground" orientation and operate in the open as a political party.[100] Members of the League eventually became persuaded in this regard. Accordingly, in June 1847 the League was reorganised by its membership into a new open "above ground" political society that appealed directly to the working classes.[101] This new open political society was called the Communist League.[102] Both Marx and Engels participated in drawing up the programme and organisational principles of the new Communist League.[103]

In late 1847, Marx and Engels began writing what was to become their most famous work – a programme of action for the Communist League. Written jointly by Marx and Engels from December 1847 to January 1848, The Communist Manifesto was first published on 21 February 1848.[104] The Communist Manifesto laid out the beliefs of the new Communist League. No longer a secret society, the Communist League wanted to make aims and intentions clear to the general public rather than hiding its beliefs as the League of the Just had been doing.[105] The opening lines of the pamphlet set forth the principal basis of Marxism: "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles".[106] It goes on to examine the antagonisms that Marx claimed were arising in the clashes of interest between the bourgeoisie (the wealthy capitalist class) and the proletariat (the industrial working class). Proceeding on from this, the Manifesto presents the argument for why the Communist League, as opposed to other socialist and liberal political parties and groups at the time, was truly acting in the interests of the proletariat to overthrow capitalist society and to replace it with socialism.[107]

Later that year, Europe experienced a series of protests, rebellions, and often violent upheavals that became known as the Revolutions of 1848.[108] In France, a revolution led to the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the French Second Republic.[108] Marx was supportive of such activity and having recently received a substantial inheritance from his father (withheld by his uncle Lionel Philips since his father's death in 1838) of either 6,000[109] or 5,000 francs[110][111] he allegedly used a third of it to arm Belgian workers who were planning revolutionary action.[111] Although the veracity of these allegations is disputed,[109][112] the Belgian Ministry of Justice accused Marx of it, subsequently arresting him and he was forced to flee back to France, where with a new republican government in power he believed that he would be safe.[111][113]

Cologne: 1848–1849[edit]

Temporarily settling down in Paris, Marx transferred the Communist League executive headquarters to the city and also set up a German Workers' Club with various German socialists living there.[114] Hoping to see the revolution spread to Germany, in 1848 Marx moved back to Cologne where he began issuing a handbill entitled the Demands of the Communist Party in Germany,[115] in which he argued for only four of the ten points of the Communist Manifesto, believing that in Germany at that time the bourgeoisie must overthrow the feudal monarchy and aristocracy before the proletariat could overthrow the bourgeoisie.[116] On 1 June, Marx started the publication of a daily newspaper, the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, which he helped to finance through his recent inheritance from his father. Designed to put forward news from across Europe with his own Marxist interpretation of events, the newspaper featured Marx as a primary writer and the dominant editorial influence. Despite contributions by fellow members of the Communist League, according to Friedrich Engels it remained "a simple dictatorship by Marx".[117][118][119]

Whilst editor of the paper, Marx and the other revolutionary socialists were regularly harassed by the police and Marx was brought to trial on several occasions, facing various allegations including insulting the Chief Public Prosecutor, committing a press misdemeanor and inciting armed rebellion through tax boycotting,[120][121] although each time he was acquitted.[122][123][124] Meanwhile, the democratic parliament in Prussia collapsed and the king, Frederick William IV, introduced a new cabinet of his reactionary supporters, who implemented counterrevolutionary measures to expunge left-wing and other revolutionary elements from the country.[125] Consequently, the Neue Rheinische Zeitung was soon suppressed and Marx was ordered to leave the country on 16 May.[119][126] Marx returned to Paris, which was then under the grip of both a reactionary counterrevolution and a cholera epidemic, and was soon expelled by the city authorities, who considered him a political threat. With his wife Jenny expecting their fourth child and with Marx not able to move back to Germany or Belgium, in August 1849 he sought refuge in London.[127][128]

Move to London and further writing: 1850–1860[edit]

Marx moved to London in early June 1849 and would remain based in the city for the rest of his life. The headquarters of the Communist League also moved to London. However, in the winter of 1849–1850, a split within the ranks of the Communist League occurred when a faction within it led by August Willich and Karl Schapper began agitating for an immediate uprising. Willich and Schapper believed that once the Communist League had initiated the uprising, the entire working class from across Europe would rise "spontaneously" to join it, thus creating revolution across Europe. Marx and Engels protested that such an unplanned uprising on the part of the Communist League was "adventuristic" and would be suicide for the Communist League.[129] Such an uprising as that recommended by the Schapper/Willich group would easily be crushed by the police and the armed forces of the reactionary governments of Europe. Marx maintained that this would spell doom for the Communist League itself, arguing that changes in society are not achieved overnight through the efforts and will power of a handful of men.[129] They are instead brought about through a scientific analysis of economic conditions of society and by moving toward revolution through different stages of social development. In the present stage of development (circa 1850), following the defeat of the uprisings across Europe in 1848 he felt that the Communist League should encourage the working class to unite with progressive elements of the rising bourgeoisie to defeat the feudal aristocracy on issues involving demands for governmental reforms, such as a constitutional republic with freely elected assemblies and universal (male) suffrage. In other words, the working class must join with bourgeois and democratic forces to bring about the successful conclusion of the bourgeois revolution before stressing the working class agenda and a working-class revolution.

After a long struggle that threatened to ruin the Communist League, Marx's opinion prevailed and eventually, the Willich/Schapper group left the Communist League. Meanwhile, Marx also became heavily involved with the socialist German Workers' Educational Society.[130] The Society held their meetings in Great Windmill Street, Soho, central London's entertainment district.[131][132] This organisation was also racked by an internal struggle between its members, some of whom followed Marx while others followed the Schapper/Willich faction. The issues in this internal split were the same issues raised in the internal split within the Communist League, but Marx lost the fight with the Schapper/Willich faction within the German Workers' Educational Society and on 17 September 1850 resigned from the Society.[133]

New-York Daily Tribune and journalism[edit]

In the early period in London, Marx committed himself almost exclusively to his studies, such that his family endured extreme poverty.[134][135] His main source of income was Engels, whose own source was his wealthy industrialist father.[135] In Prussia as editor of his own newspaper, and contributor to others ideologically aligned, Marx could reach his audience, the working classes. In London, without finances to run a newspaper themselves, he and Engels turned to international journalism. At one stage they were being published by six newspapers from England, the United States, Prussia, Austria, and South Africa.[136] Marx's principal earnings came from his work as European correspondent, from 1852 to 1862, for the New-York Daily Tribune,[137]: 17 and from also producing articles for more "bourgeois" newspapers. Marx had his articles translated from German by Wilhelm Pieper, until his proficiency in English had become adequate.[138]

The New-York Daily Tribune had been founded in April 1841 by Horace Greeley.[139] Its editorial board contained progressive bourgeois journalists and publishers, among them George Ripley and the journalist Charles Dana, who was editor-in-chief. Dana, a fourierist and an abolitionist, was Marx's contact. The Tribune was a vehicle for Marx to reach a transatlantic public, such as for his "hidden warfare" against Henry Charles Carey.[140] The journal had wide working-class appeal from its foundation; at two cents, it was inexpensive;[141] and, with about 50,000 copies per issue, its circulation was the widest in the United States.[137]: 14 Its editorial ethos was progressive and its anti-slavery stance reflected Greeley's.[137]: 82 Marx's first article for the paper, on the British parliamentary elections, was published on 21 August 1852.[142]

On 21 March 1857, Dana informed Marx that due to the economic recession only one article a week would be paid for, published or not; the others would be paid for only if published. Marx had sent his articles on Tuesdays and Fridays, but, that October, the Tribune discharged all its correspondents in Europe except Marx and B. Taylor, and reduced Marx to a weekly article. Between September and November 1860, only five were published. After a six-month interval, Marx resumed contributions from September 1861 until March 1862, when Dana wrote to inform him that there was no longer space in the Tribune for reports from London, due to American domestic affairs.[143]

In 1868, Dana set up a rival newspaper, the New York Sun, at which he was editor-in-chief.[144] In April 1857, Dana invited Marx to contribute articles, mainly on military history, to the New American Cyclopedia, an idea of George Ripley, Dana's friend and literary editor of the Tribune. In all, 67 Marx-Engels articles were published, of which 51 were written by Engels, although Marx did some research for them in the British Museum.[145] By the late 1850s, American popular interest in European affairs waned and Marx's articles turned to topics such as the "slavery crisis" and the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 in the "War Between the States".[146] Between December 1851 and March 1852, Marx worked on his theoretical work about the French Revolution of 1848, titled The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon.[147] In this he explored concepts in historical materialism, class struggle, dictatorship of the proletariat, and victory of the proletariat over the bourgeois state.[148]

The 1850s and 1860s may be said to mark a philosophical boundary distinguishing the young Marx's Hegelian idealism and the more mature Marx's[149][150][151][152] scientific ideology associated with structural Marxism.[152] However, not all scholars accept this distinction.[151][153] For Marx and Engels, their experience of the Revolutions of 1848 to 1849 were formative in the development of their theory of economics and historical progression. After the "failures" of 1848, the revolutionary impetus appeared spent and not to be renewed without an economic recession. Contention arose between Marx and his fellow communists, whom he denounced as "adventurists". Marx deemed it fanciful to propose that "will power" could be sufficient to create the revolutionary conditions when in reality the economic component was the necessary requisite. The recession in the United States' economy in 1852 gave Marx and Engels grounds for optimism for revolutionary activity, yet this economy was seen as too immature for a capitalist revolution. Open territories on America's western frontier dissipated the forces of social unrest. Moreover, any economic crisis arising in the United States would not lead to revolutionary contagion of the older economies of individual European nations, which were closed systems bounded by their national borders. When the so-called Panic of 1857 in the United States spread globally, it broke all economic theory models, and was the first truly global economic crisis.[154]

Financial necessity had forced Marx to abandon economic studies in 1844 and give thirteen years to working on other projects. He had always sought to return to economics.[citation needed]

First International and Das Kapital[edit]

Marx continued to write articles for the New York Daily Tribune as long as he was sure that the Tribune's editorial policy was still progressive. However, the departure of Charles Dana from the paper in late 1861 and the resultant change in the editorial board brought about a new editorial policy.[155] No longer was the Tribune to be a strong abolitionist paper dedicated to a complete Union victory. The new editorial board supported an immediate peace between the Union and the Confederacy in the Civil War in the United States with slavery left intact in the Confederacy. Marx strongly disagreed with this new political position and in 1863 was forced to withdraw as a writer for the Tribune.[156]

In 1864, Marx became involved in the International Workingmen's Association (also known as the First International),[122] to whose General Council he was elected at its inception in 1864.[157] In that organisation, Marx was involved in the struggle against the anarchist wing centred on Mikhail Bakunin (1814–1876).[135] Although Marx won this contest, the transfer of the seat of the General Council from London to New York in 1872, which Marx supported, led to the decline of the International.[158] The most important political event during the existence of the International was the Paris Commune of 1871 when the citizens of Paris rebelled against their government and held the city for two months. In response to the bloody suppression of this rebellion, Marx wrote one of his most famous pamphlets, "The Civil War in France", a defence of the Commune.[159][160]

Given the repeated failures and frustrations of workers' revolutions and movements, Marx also sought to understand and provide a critique suitable for the capitalist mode of production, and hence spent a great deal of time in the reading room of the British Museum studying.[161] By 1857, Marx had accumulated over 800 pages of notes and short essays on capital, landed property, wage labour, the state, and foreign trade, and the world market, though this work did not appear in print until 1939, under the title Outlines of the Critique of Political Economy.[162][163][164]

In 1859, Marx published A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy,[165] his first serious critique of political economy. This work was intended merely as a preview of his three-volume Das Kapital (English title: Capital: Critique of Political Economy), which he intended to publish at a later date. In A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Marx began to critically examine axioms and categories of economic thinking.[166][167][168] The work was enthusiastically received, and the edition sold out quickly.[169]

The successful sales of A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy stimulated Marx in the early 1860s to finish work on the three large volumes that would compose his major life's work – Das Kapital and the Theories of Surplus Value, which discussed and critiqued the theoreticians of political economy, particularly Adam Smith and David Ricardo.[135] Theories of Surplus Value is often referred to as the fourth volume of Das Kapital and constitutes one of the first comprehensive treatises on the history of economic thought.[170] In 1867, the first volume of Das Kapital was published, a work which critically analysed capital.[171][168] Das Kapital proposes an explanation of the "laws of motion" of the mode of production from its origins to its future by describing the dynamics of the accumulation of capital, with topics such as the growth of wage labour, the transformation of the workplace, capital accumulation, competition, the banking system, the tendency of the rate of profit to fall and land-rents, as well as how waged labour continually reproduce the rule of capital.[172][173][174] Marx proposes that the driving force of capital is in the exploitation of labor, whose unpaid work is the ultimate source of surplus value.

Demand for a Russian language edition of Das Kapital soon led to the printing of 3,000 copies of the book in the Russian language, which was published on 27 March 1872. By the autumn of 1871, the entire first edition of the German-language edition of Das Kapital had been sold out and a second edition was published.

Volumes II and III of Das Kapital remained mere manuscripts upon which Marx continued to work for the rest of his life. Both volumes were published by Engels after Marx's death.[135] Volume II of Das Kapital was prepared and published by Engels in July 1893 under the name Capital II: The Process of Circulation of Capital.[175] Volume III of Das Kapital was published a year later in October 1894 under the name Capital III: The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole.[176] Theories of Surplus Value derived from the sprawling Economic Manuscripts of 1861–1863, a second draft for Das Kapital, the latter spanning volumes 30–34 of the Collected Works of Marx and Engels. Specifically, Theories of Surplus Value runs from the latter part of the Collected Works' thirtieth volume through the end of their thirty-second volume;[177][178][179] meanwhile, the larger Economic Manuscripts of 1861–1863 run from the start of the Collected Works' thirtieth volume through the first half of their thirty-fourth volume. The latter half of the Collected Works' thirty-fourth volume consists of the surviving fragments of the Economic Manuscripts of 1863–1864, which represented a third draft for Das Kapital, and a large portion of which is included as an appendix to the Penguin edition of Das Kapital, volume I.[180] A German-language abridged edition of Theories of Surplus Value was published in 1905 and in 1910. This abridged edition was translated into English and published in 1951 in London, but the complete unabridged edition of Theories of Surplus Value was published as the "fourth volume" of Das Kapital in 1963 and 1971 in Moscow.[181]

During the last decade of his life, Marx's health declined and he became incapable of the sustained effort that had characterised his previous work.[135] He did manage to comment substantially on contemporary politics, particularly in Germany and Russia. His Critique of the Gotha Programme opposed the tendency of his followers Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel to compromise with the state socialist ideas of Ferdinand Lassalle in the interests of a united socialist party.[135] This work is also notable for another famous Marx quote: "From each according to his ability, to each according to his need".[182]

In a letter to Vera Zasulich dated 8 March 1881, Marx contemplated the possibility of Russia's bypassing the capitalist stage of development and building communism on the basis of the common ownership of land characteristic of the village mir.[135][183] While admitting that Russia's rural "commune is the fulcrum of social regeneration in Russia", Marx also warned that in order for the mir to operate as a means for moving straight to the socialist stage without a preceding capitalist stage it "would first be necessary to eliminate the deleterious influences which are assailing it [the rural commune] from all sides".[184] Given the elimination of these pernicious influences, Marx allowed that "normal conditions of spontaneous development" of the rural commune could exist.[184] However, in the same letter to Vera Zasulich he points out that "at the core of the capitalist system ... lies the complete separation of the producer from the means of production".[184] In one of the drafts of this letter, Marx reveals his growing passion for anthropology, motivated by his belief that future communism would be a return on a higher level to the communism of our prehistoric past. He wrote that "the historical trend of our age is the fatal crisis which capitalist production has undergone in the European and American countries where it has reached its highest peak, a crisis that will end in its destruction, in the return of modern society to a higher form of the most archaic type – collective production and appropriation". He added that "the vitality of primitive communities was incomparably greater than that of Semitic, Greek, Roman, etc. societies, and, a fortiori, that of modern capitalist societies".[185] Before he died, Marx asked Engels to write up these ideas, which were published in 1884 under the title The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State.

Personal life[edit]

Family[edit]

Marx and von Westphalen had seven children together, but partly owing to the poor conditions in which they lived whilst in London, only three survived to adulthood.[186] Their children were: Jenny Caroline (m. Longuet; 1844–1883); Jenny Laura (m. Lafargue; 1845–1911); Edgar (1847–1855); Henry Edward Guy ("Guido"; 1849–1850); Jenny Eveline Frances ("Franziska"; 1851–1852); Jenny Julia Eleanor (1855–1898) and one more who died before being named (July 1857). According to his son-in-law, Paul Lafargue, Marx was a loving father.[187] In 1962, there were allegations that Marx fathered a son, Freddy,[188] out of wedlock by his housekeeper, Helene Demuth,[189] but the claim is disputed for lack of documented evidence.[190]

Marx frequently used pseudonyms, often when renting a house or flat, apparently to make it harder for the authorities to track him down. While in Paris, he used that of "Monsieur Ramboz", whilst in London, he signed off his letters as "A. Williams". His friends referred to him as "Moor", owing to his dark complexion and black curly hair, while he encouraged his children to call him "Old Nick" and "Charley".[191] He also bestowed nicknames and pseudonyms on his friends and family as well, referring to Friedrich Engels as "General", his housekeeper Helene as "Lenchen" or "Nym", while one of his daughters, Jennychen, was referred to as "Qui Qui, Emperor of China" and another, Laura, was known as "Kakadou" or "the Hottentot".[191]

Health[edit]

Marx drank heavily until his death after joining the Trier Tavern Club drinking society in the 1830s.[30]

Marx was afflicted by poor health (what he himself described as "the wretchedness of existence")[192] and various authors have sought to describe and explain it. His biographer Werner Blumenberg attributed it to liver and gall problems which Marx had in 1849 and from which he was never afterward free, exacerbated by an unsuitable lifestyle. The attacks often came with headaches, eye inflammation, neuralgia in the head, and rheumatic pains. A serious nervous disorder appeared in 1877 and protracted insomnia was a consequence, which Marx fought with narcotics. The illness was aggravated by excessive nocturnal work and faulty diet. Marx was fond of highly seasoned dishes, smoked fish, caviare, pickled cucumbers, "none of which are good for liver patients", but he also liked wine and liqueurs and smoked an enormous amount "and since he had no money, it was usually bad-quality cigars". From 1863, Marx complained a lot about boils: "These are very frequent with liver patients and may be due to the same causes".[193] The abscesses were so bad that Marx could neither sit nor work upright. According to Blumenberg, Marx's irritability is often found in liver patients:

The illness emphasised certain traits in his character. He argued cuttingly, his biting satire did not shrink at insults, and his expressions could be rude and cruel. Though in general Marx had blind faith in his closest friends, nevertheless he himself complained that he was sometimes too mistrustful and unjust even to them. His verdicts, not only about enemies but even about friends, were sometimes so harsh that even less sensitive people would take offence ... There must have been few whom he did not criticize like this ... not even Engels was an exception.[194]

According to Princeton historian Jerrold Seigel, in his late teens, Marx may have had pneumonia or pleurisy, the effects of which led to his being exempted from Prussian military service. In later life whilst working on Das Kapital (which he never completed),[192][195] Marx suffered from a trio of afflictions. A liver ailment, probably hereditary, was aggravated by overwork, a bad diet, and lack of sleep. Inflammation of the eyes was induced by too much work at night. A third affliction, eruption of carbuncles or boils, "was probably brought on by general physical debility to which the various features of Marx's style of life – alcohol, tobacco, poor diet, and failure to sleep – all contributed. Engels often exhorted Marx to alter this dangerous regime". In Seigel's thesis, what lay behind this punishing sacrifice of his health may have been guilt about self-involvement and egoism, originally induced in Karl Marx by his father.[196]