User:Blackcara100/sandbox

Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (1977–2011) [edit]

Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (1977–1986) الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الاشتراكية al-Jamāhīrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Lībīyah ash-Sha'bīyah al-Ishtirākīyah Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (1986–2011) الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الإشتراكية العظمى al-Jamāhīrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Lībīyah ash-Sha'bīyah al-Ishtirākīyah al-'Uẓmá | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1977–2011 | |||||||||

| Motto: وحدة ، حرية ، اشتراكية Waḥdah, Ḥurrīyah, Ishtirākīyah ("Unity, Freedom, Socialism") | |||||||||

| Anthem: الله أكبر Allahu Akbar ("God is Great") | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Tripoli (1977–2011) Sirte (2011)[1] 32°52′N 13°11′E / 32.867°N 13.183°E | ||||||||

| Largest city | Tripoli | ||||||||

| Official languages | Arabic[b] | ||||||||

| Spoken languages | |||||||||

| Minority Languages | |||||||||

| Ethnic groups |

| ||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary Islamic socialist Jamahiriya | ||||||||

| Brotherly Leader and Guide of the Revolution | |||||||||

• 1977–2011 | Muammar Gaddafi | ||||||||

| Secretary-General of the General People's Congress (head of state and head of legislature) | |||||||||

• 1977–1979 (first) | Muammar Gaddafi | ||||||||

• 2010–2011 (last) | Mohamed Abu al-Qasim al-Zwai | ||||||||

| Secretary-General of the General People's Committee (head of government) | |||||||||

• 1977–1979 (first) | Abdul Ati al-Obeidi | ||||||||

• 2006–2011 (last) | Baghdadi Mahmudi | ||||||||

| Legislature | General People's Congress | ||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War · War on Terror · Arab Spring | ||||||||

| 2 March 1977 | |||||||||

| 15 February 2011 | |||||||||

| 28 August 2011 | |||||||||

| 20 October 2011 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• Total | 1,759,541 km2 (679,363 sq mi) (16th) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 2010 | 6,355,100 | ||||||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2007 estimate | ||||||||

• Total | |||||||||

• Per capita | |||||||||

| HDI (2009) | very high | ||||||||

| Currency | Libyan dinar (LYD) | ||||||||

| Calling code | 218 | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | LY | ||||||||

| |||||||||

On 2 March 1977, the General People's Congress (GPC), at Gaddafi's behest, adopted the "Declaration of the Establishment of the People's Authority"[5][6] and proclaimed the Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (Arabic: الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الاشتراكية[7] al-Jamāhīrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Lībīyah ash-Sha'bīyah al-Ishtirākīyah). In the official political philosophy of Gaddafi's state, the "Jamahiriya" system was unique to the country, although it was presented as the materialization of the Third International Theory, proposed by Gaddafi to be applied to the entire Third World. The GPC also created the General Secretariat of the GPC, comprising the remaining members of the defunct Revolutionary Command Council, with Gaddafi as general secretary, and also appointed the General People's Committee, which replaced the Council of Ministers, its members now called secretaries rather than ministers.

The Libyan government claimed that the Jamahiriya was a direct democracy without any political parties, governed by its populace through local popular councils and communes (named Basic People's Congresses). Official rhetoric disdained the idea of a nation state, tribal bonds remaining primary, even within the ranks of the national army.[8]

Etymology[edit]

Jamahiriya (Arabic: جماهيرية jamāhīrīyah) is an Arabic term generally translated as "state of the masses"; Lisa Anderson[9] has suggested "peopledom" or "state of the masses" as a reasonable approximations of the meaning of the term as intended by Gaddafi. The term does not occur in this sense in Muammar Gaddafi's Green Book of 1975. The nisba-adjective jamāhīrīyah ("mass-, "of the masses") occurs only in the third part, published in 1981, in the phrase إن الحركات التاريخية هي الحركات الجماهيرية (Inna al-ḥarakāt at-tārīkhīyah hiya al-ḥarakāt al-jamāhīrīyah), translated in the English edition as "Historic movements are mass movements".

The word jamāhīrīyah was derived from jumhūrīyah, which is the usual Arabic translation of "republic". It was coined by changing the component jumhūr—"public"—to its plural form, jamāhīr—"the masses". Thus, it is similar to the term People's Republic. It is often left untranslated in English, with the long-form name thus rendered as Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. However, in Hebrew, for instance, jamāhīrīyah is translated as "קהילייה" (qehiliyáh), a word also used to translate the term "Commonwealth" when referring to the designation of a country.

After weathering the 1986 U.S. bombing by the Reagan administration, Gaddafi added the specifier "Great" (العظمى al-'Uẓmá) to the official name of the country.

Reforms (1977–1980)[edit]

Gaddafi as permanent "Brotherly Leader and Guide of the Revolution"[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

The changes in Libyan leadership since 1976 culminated in March 1979, when the General People's Congress declared that the "vesting of power in the masses" and the "separation of the state from the revolution" were complete. The government was divided into two parts, the "Jamahiriya sector" and the "revolutionary sector". The "Jamahiriya sector" was composed of the General People's Congress, the General People's Committee, and the local Basic People's Congresses. Gaddafi relinquished his position as general secretary of the General People's Congress, as which he was succeeded by Abdul Ati al-Obeidi, who had been prime minister since 1977.

The "Jamahiriya sector" was overseen by the "revolutionary sector", headed by Gaddafi as "Leader of the Revolution" (Qā'id)A and the surviving members of the Revolutionary Command Council. The leaders of the revolutionary sector were not subject to election, as they owed office to their role in the 1969 coup. They oversaw the "revolutionary committees", which were nominally grass-roots organizations that helped keep the people engaged. As a result, although Gaddafi held no formal government office after 1979, he retained control of the government and the country.[citation needed] Gaddafi also remained supreme commander of the armed forces.

Administrative reforms[edit]

All legislative and executive authority was vested in the GPC. This body, however, delegated most of its important authority to its general secretary and General Secretariat and to the General People's Committee. Gaddafi, as general secretary of the GPC, remained the primary decision maker, just as he had been when chairman of the RCC. In turn, all adults had the right and duty to participate in the deliberation of their local Basic People's Congress (BPC), whose decisions were passed up to the GPC for consideration and implementation as national policy. The BPCs were in theory the repository of ultimate political authority and decision making, embodying what Gaddafi termed direct "people's power". The 1977 declaration and its accompanying resolutions amounted to a fundamental revision of the 1969 constitutional proclamation, especially with respect to the structure and organization of the government at both national and subnational levels.

Continuing to revamp Libya's political and administrative structure, Gaddafi introduced yet another element into the body politic. Beginning in 1977, "revolutionary committees" were organized and assigned the task of "absolute revolutionary supervision of people's power"; that is, they were to guide the people's committees, "raise the general level of political consciousness and devotion to revolutionary ideals". In reality, the revolutionary committees were used to survey the population and repress any political opposition to Gaddafi's autocratic rule. Reportedly 10% to 20% of Libyans worked in surveillance for these committees, a proportion of informants on par with Ba'athist Iraq and Juche Korea.[10]

Filled with politically astute zealots, the ubiquitous revolutionary committees in 1979 assumed control of BPC elections. Although they were not official government organs, the revolutionary committees became another mainstay of the domestic political scene. As with the people's committees and other administrative innovations since the revolution, the revolutionary committees fit the pattern of imposing a new element on the existing subnational system of government rather than eliminating or consolidating already existing structures. By the late 1970s, the result was an unnecessarily complex system of overlapping jurisdictions in which cooperation and coordination among different elements were compromised by ill-defined authority and responsibility. The ambiguity may have helped serve Gaddafi's aim to remain the prime mover behind Libyan governance, while minimizing his visibility at a time when internal opposition to political repression was rising.

The RCC was formally dissolved and the government was again reorganized into people's committees. A new General People's Committee (cabinet) was selected, each of its "secretaries" becoming head of a specialized people's committee; the exceptions were the "secretariats" of petroleum, foreign affairs, and heavy industry, where there were no people's committees. A proposal was also made to establish a "people's army" by substituting a national militia, being formed in the late 1970s, for the national army. Although the idea surfaced again in early 1982, it did not appear to be close to implementation.

Gaddafi also wanted to combat the strict social restrictions that had been imposed on women by the previous regime, establishing the Revolutionary Women's Formation to encourage reform. In 1970, a law was introduced affirming equality of the sexes and insisting on wage parity. In 1971, Gaddafi sponsored the creation of a Libyan General Women's Federation. In 1972, a law was passed criminalizing the marriage of any females under the age of sixteen and ensuring that a woman's consent was a necessary prerequisite for a marriage.[11]

Economic reforms[edit]

Remaking of the economy was parallel with the attempt to remold political and social institutions. Until the late 1970s, Libya's economy was mixed, with a large role for private enterprise except in the fields of oil production and distribution, banking, and insurance. But according to volume two of Gaddafi's Green Book, which appeared in 1978, private retail trade, rent, and wages were forms of exploitation that should be abolished. Instead, workers' self-management committees and profit participation partnerships were to function in public and private enterprises.

A property law was passed that forbade ownership of more than one private dwelling, and Libyan workers took control of a large number of companies, turning them into state-run enterprises. Retail and wholesale trading operations were replaced by state-owned "people's supermarkets", where Libyans in theory could purchase whatever they needed at low prices. By 1981 the state had also restricted access to individual bank accounts to draw upon privately held funds for government projects. The measures created resentment and opposition among the newly dispossessed. The latter joined those already alienated, some of whom had begun to leave the country. By 1982, perhaps 50,000 to 100,000 Libyans had gone abroad; because many of the emigrants were among the enterprising and better educated Libyans, they represented a significant loss of managerial and technical expertise.

The government also built a trans-Sahara water pipeline from major aquifers to both a network of reservoirs and the towns of Tripoli, Sirte and Benghazi in 2006–2007.[12] It is part of the Great Manmade River project, started in 1984. It is pumping large resources of water from the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System to both urban populations and new irrigation projects around the country.[13]

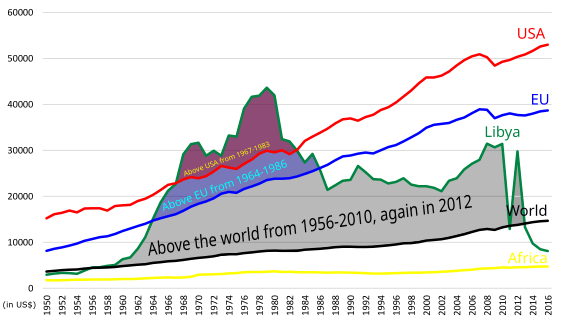

Libya continued to be plagued with a shortage of skilled labor, which had to be imported along with a broad range of consumer goods, both paid for with petroleum income. The country consistently ranked as the African nation with the highest HDI, standing at 0.755 in 2010, which was 0.041 higher than the next highest African HDI that same year.[14] Gender equality was a major achievement under Gaddafi's rule. According to Lisa Anderson, president of the American University in Cairo and an expert on Libya, said that under Gaddafi more women attended university and had "dramatically" more employment opportunities than most Arab nations.[15]

Military[edit]

Wars against Chad and Egypt[edit]

As early as 1969, Gaddafi waged a campaign against Chad. Scholar Gerard Prunier claims part of his hostility was apparently because Chadian President François Tombalbaye was Christian.[16] Libya was also involved in a sometimes violent territorial dispute with neighbouring Chad over the Aouzou Strip, which Libya occupied in 1973. This dispute eventually led to the Libyan invasion of Chad. The prolonged foray of Libyan troops into the Aozou Strip in northern Chad, was finally repulsed in 1987, when extensive US and French help to Chadian rebel forces and the government headed by former Defence Minister Hissein Habré finally led to a Chadian victory in the so-called Toyota War. The conflict ended in a ceasefire in 1987. After a judgement of the International Court of Justice on 13 February 1994, Libya withdrew troops from Chad the same year and the dispute was settled.[17]

In 1977, Gaddafi dispatched his military across the border to Egypt, but Egyptian forces fought back in the Libyan–Egyptian War. Both nations agreed to a ceasefire under the mediation of the President of Algeria Houari Boumediène.[18]

Islamic Legion[edit]

In 1972, Gaddafi created the Islamic Legion as a tool to unify and Arabize the region. The priority of the Legion was first Chad, and then Sudan. In Darfur, a western province of Sudan, Gaddafi supported the creation of the Arab Gathering (Tajammu al-Arabi), which according to Gérard Prunier was "a militantly racist and pan-Arabist organization which stressed the 'Arab' character of the province."[19] The two organizations shared members and a source of support, and the distinction between them is often ambiguous.

This Islamic Legion was mostly composed of immigrants from poorer Sahelian countries,[20] but also, according to a source, thousands of Pakistanis who had been recruited in 1981 with the false promise of civilian jobs once in Libya.[21] Generally speaking, the Legion's members were immigrants who had gone to Libya with no thought of fighting wars, and had been provided with inadequate military training and had sparse commitment. A French journalist, speaking of the Legion's forces in Chad, observed that they were "foreigners, Arabs or Africans, mercenaries in spite of themselves, wretches who had come to Libya hoping for a civilian job, but found themselves signed up more or less by force to go and fight in an unknown desert."[20]

At the beginning of the 1987 Libyan offensive in Chad, it maintained a force of 2,000 in Darfur. The nearly continuous cross-border raids that resulted greatly contributed to a separate ethnic conflict within Darfur that killed about 9,000 people between 1985 and 1988.[22]

Janjaweed, a group accused by the US of carrying out a genocide in Darfur in the 2000s, emerged in 1988 and some of its leaders are former legionnaires.[23]

Attempts at nuclear and chemical weapons[edit]

In 1972, Gaddafi tried to buy a nuclear bomb from the People's Republic of China. He then tried to get a bomb from Pakistan, but Pakistan severed its ties before it succeeded in building a bomb.[24] In 1978, Gaddafi turned to Pakistan's rival, India, for help building its own nuclear bomb.[25] In July 1978, Libya and India signed a memorandum of understanding to cooperate in peaceful applications of nuclear energy as part of India's Atom of Peace policy.[25] In 1991, then Prime Minister Navaz Sharif paid a state visit to Libya to hold talks on the promotion of a Free Trade Agreement between Pakistan and Libya.[26] However, Gaddafi focused on demanding Pakistan's Prime Minister sell him a nuclear weapon, which surprised many of the Prime Minister's delegation members and journalists.[26] When Prime minister Sharif refused Gaddafi's demand, Gaddafi disrespected him, calling him a "Corrupt politician", a term which insulted and surprised Sharif.[26] The Prime minister cancelled the talks, returned to Pakistan and expelled the Libyan Ambassador from Pakistan.[26]

Thailand reported its citizens had helped build storage facilities for nerve gas.[27] Germany sentenced a businessman, Jurgen Hippenstiel-Imhausen, to five years in prison for involvement in Libyan chemical weapons.[24][28] Inspectors from the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) verified in 2004 that Libya owned a stockpile of 23 metric tons of mustard gas and more than 1,300 metric tons of precursor chemicals.[29]

Gulf of Sidra incidents and US air strikes[edit]

When Libya was under pressure from international disputes, on 19 August 1981, a naval dogfight occurred over the Gulf of Sirte in the Mediterranean Sea. US F-14 Tomcat jets fired anti-aircraft missiles against a formation of Libyan fighter jets in this dogfight and shot down two Libyan Su-22 Fitter attack aircraft. This naval action was a result of claiming the territory and losses from the previous incident. A second dogfight occurred on 4 January 1989; US carrier-based jets also shot down two Libyan MiG-23 Flogger-Es in the same place.

A similar action occurred on 23 March 1986; while patrolling the Gulf, US naval forces attacked a sizable naval force and various SAM sites defending Libyan territory. US fighter jets and fighter-bombers destroyed SAM launching facilities and sank various naval vessels, killing 35 seamen. This was a reprisal for terrorist hijackings between June and December 1985.

On 5 April 1986, Libyan agents bombed "La Belle" nightclub in West Berlin, killing three and injuring 229. Gaddafi's plan was intercepted by several national intelligence agencies and more detailed information was retrieved four years later from Stasi archives. The Libyan agents who had carried out the operation, from the Libyan embassy in East Germany, were prosecuted by the reunited Germany in the 1990s.[30]

In response to the discotheque bombing, joint US Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps air-strikes took place against Libya on 15 April 1986 and code-named Operation El Dorado Canyon and known as the 1986 bombing of Libya. Air defenses, three army bases, and two airfields in Tripoli and Benghazi were bombed. The surgical strikes failed to kill Gaddafi but he lost a few dozen military officers. Gaddafi spread propaganda how it had killed his "adopted daughter" and how victims had been all "civilians". Despite the variations of the stories, the campaign was successful, and a large proportion of the Western press reported the government's stories as facts.[31]: 141

Following the 1986 bombing of Libya, Gaddafi intensified his support for anti-American government organizations. He financed Jeff Fort's Al-Rukn faction of the Chicago Black P. Stones gang, in their emergence as an indigenous anti-American armed revolutionary movement.[32] Al-Rukn members were arrested in 1986 for preparing strikes on behalf of Libya, including blowing up US government buildings and bringing down an airplane; the Al-Rukn defendants were convicted in 1987 of "offering to commit bombings and assassinations on US soil for Libyan payment."[32] In 1986, Libyan state television announced that Libya was training suicide squads to attack American and European interests. He began financing the IRA again in 1986, to retaliate against the British for harboring American fighter planes.[33]

Gaddafi announced that he had won a spectacular military victory over the US and the country was officially renamed the "Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriyah".[31]: 183 However, his speech appeared devoid of passion and even the "victory" celebrations appeared unusual. Criticism of Gaddafi by ordinary Libyan citizens became more bold, such as defacing of Gaddafi posters.[31]: 183 The raids against Libyan military had brought the government to its weakest point in 17 years.[31]: 183

- ^ "Libya crisis: Col Gaddafi vows to fight a 'long war'". BBC News. 1 September 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ "L'Aménagement Linguistique dans le Monde - Libye". Archived from the original on 26 April 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2009" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2014.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2009" (PDF). hdr.undp.org.

- ^ General People's Congress declaration (2 March 1977) at EMERglobal Lex Archived 19 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine for the Edinburgh Middle East Report. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ^ "ICL - Libya - Declaration on the Establishment of the Authority of the People". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ Geographical Names, "اَلْجَمَاهِيرِيَّة اَلْعَرَبِيَّة اَللِّيبِيَّة اَلشَّعْبِيَّة اَلإِشْتِرَاكِيَّة: Libya" Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Geographic.org. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ Protesters Die as Crackdown in Libya Intensifies Archived 6 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 20 February 2011; accessed 20 February 2011.

- ^ "Libya – The Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya". Countrystudies.us. Archived from the original on 29 August 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ Eljahmi, Mohamed (2006). "Libya and the U.S.: Gaddafi Unrepentant". Middle East Quarterly. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ Bearman, Jonathan (1986). Qadhafi's Libya. London: Zed Books.[page needed]

- ^ "BBC Info on Trans-Sahara Water Pipelines" Archived 27 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News.

- ^ Luxner, Larry (October 2010). "Libya's 'Eighth Wonder of the World'". BNET (via FindArticles).

- ^ Human Development Index (HDI) – 2010 Rankings Archived 12 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations Development Programme

- ^ "Gaddafi: Emancipator of women?". IOL. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ Prunier, Gérard. Darfur – A 21st Century Genocide. p. 44.

- ^ "judgment of the ICJ of 13 February 1994" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2004. Retrieved 8 January 2007.

- ^ "Eugene Register-Guard - Google News Archive Search". Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ Prunier, Gérard. Darfur: The Ambiguous Genocide. p. 45.

- ^ a b Nolutshungu, S. p. 220.

- ^ Thomson, J. Mercenaries, Pirates and Sovereigns. p. 91.

- ^ Prunier, G. pp. 61–65.

- ^ de Waal, Alex (5 August 2004). "Counter-Insurgency on the Cheap". London Review of Books. 26 (15). Archived from the original on 3 August 2004. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Libya Has Trouble Building the Most Deadly Weapons". The Risk Report Volume 1 Number 10 (December 1995). Archived from the original on 20 April 2013.

- ^ a b "Libyan nuclear programme". globalsecurity.org. GlobalSecurity.org and John E. Pike. Archived from the original on 29 August 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d Khalil, Tahier. "Gaddafi made an enormest effort for Bhutto's release". Tahir Khalil of Jang Media Group. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Lifetimesgroup News". April 2011. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ "Libyan Chemical Weapons" Archived 29 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. GlobalSecurity.org.

- ^ "Libya Chemical Weapons Destruction Costly". Arms Control Association. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ Flashback: The Berlin disco bombing Archived 27 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. BBC on 13 November 2001.

- ^ a b c d Davis, Brian Lee (1990). Qaddafi, Terrorism, and the Origins of the U.S. Attack on Libya.

- ^ a b Bodansky, Yossef (1993). Target America & the West: Terrorism Today. New York: S.P.I. Books. pp. 301–303. ISBN 978-1-56171-269-4.

- ^ Kelsey, Tim; Koenig, Peter (20 July 1994). "Libya will not arm IRA again, Gaddafi aide says". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 25 March 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2011.