Tunisian tortoise

| Tunisian tortoise | |

|---|---|

| |

| Testudo graeca nabeulensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Testudinidae |

| Genus: | Testudo |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | T. g. nabeulensis

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Testudo graeca nabeulensis Highfield, 1990[1]

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

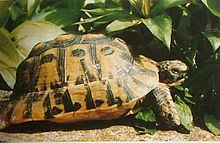

The Tunisian tortoise or Nabeul tortoise (Testudo graeca nabeulensis) is a subspecies of Greek tortoises. It was originally described as a new species in 1990, and even placed in a distinct genus. The spur-thighed or "Greek" tortoises are usually collectively referred to as Testudo graeca, but this covers a wide variety of subspecies that have very different ecological and morphological characteristics and appear to comprise at least three phylogenetic lineages.[2] As its name implies, it is found in Tunisia and nearby Algeria.

Description and ecology[edit]

The Tunisian tortoise is a relatively small tortoise. The adult males usually have carapaces that seldom exceed 13 cm (about 4.5 in), whilst the adult females' carapaces are no more than 16.5 cm (some 6.5 in) long. The geographically closest population of the T. graeca group, from Morocco, is decidedly larger.

These tortoises are among the most brightly colored taxa of the spur-thighed or Greek tortoise complex, with a light yellow carapace with strong black markings in the scute centers. The plastron also has a bold color pattern. On the top of the head, right between the eyes, is a distinct yellowish spot.

Tunisian tortoises are popular as pets due to their attractive coloration and small size. They are a bit more delicate than their larger relatives, though their care is not particularly difficult, they are not ideal pets for those who have no experience at all in keeping tortoises. Coming from tropical semiarid habitat, they do not hibernate, and an attempt to have them do so will cause a fatality. This does actually make their care easier for people in warmer regions, but in temperate climates, they require a well-heated and amply lit terrarium even in winter.

Systematics[edit]

The genus Furculachelys was established for this taxon and "White's tortoise" (or "Selborne tortoise"). The latter seems to be a local morph rather than a distinct subspecies, however. In any case, separating a form that is in all respects a perfectly ordinary Testudo, compared to more distinct species such as the Russian tortoise seems to be gross oversplitting, making Testudo paraphyletic.[citation needed]

Treatment as a distinct subspecies is also not supported by mtDNA 12S rRNA haplotype analysis. However, these results still seem to confirm that the Tunisian tortoise constitutes a well-marked lineage of Greek tortoises. The T. graeca complex is likely to be split into (at least) three species in the near future; the eastern Maghreb populations would remain in T. graeca in this case. Consequently, the scientific name that agrees best with the collected evidence would presently be T. graeca nabeulensis. As said above, however, apart from the Balkans and Eastern populations of the T. graeca complex, the present taxon seems to be quite distinct, too. As the former two lineages will eventually come to represent good species, the Tunisian tortoise might also be regarded as specifically distinct.[2]

Some unresolved questions remain regarding the relationships of two populations of Greek tortoises. The Libyan population was described as Testudo flavominimaralis in the same publication which established "F." nabeulensis. These two are rather similar to each other and as noted above, the separation of Furculachelys is highly dubious on these grounds alone. If the eastern Maghreb tortoises are regarded as a distinct species, it is not unlikely that the Libyan population is united with them as a subspecies.[citation needed]

On Sardinia, a population of Greek tortoises shares the small size, the yellow head spot, and the contrasting markings with the Tunisian population. Their taxonomic status is enigmatic, as is their very existence on the island, separated from North Africa by a considerable stretch of the Mediterranean which tortoises are hardly able to cross. There is a distinct local form of the marginated tortoise on the island, however, and that seems to have originated from a deliberate introduction by humans, perhaps by Greek or Roman landowners in the classical antiquity.[3] While the local marginated tortoises show evidence of pronounced genetic drift and may thus justifiably regarded as a subspecies despite the absence of lineage sorting, the Greek tortoises of Sardinia are probably best considered an introduced population not yet worthy of taxonomic separation pending further research.

Nonetheless, because the present taxon may well turn out not to be limited to Tunisia and its immediate surroundings, the alternative common name Nabeul tortoise might actually be preferable. It is a literal translation of the scientific name and honors the Tunisian city of Nabeul, where the type material was collected. Even if this fact were generally known, it is not very likely that anyone would believe these animals are endemic to a single city.[citation needed]

-

Juvenile Greek tortoise proper (T. (g.) ibera, left) and Tunisian tortoise (right), carapace

-

Juvenile Greek tortoise proper (T. (g.) ibera, left) and Tunisian tortoise (right), plastron

-

Greek tortoise from Sardinia, note the yellow head spot

-

Greek tortoises from Sardinia: plastron of male (left) and female (right)

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Rhodin, Anders G.J.; van Dijk, Peter Paul; Inverson, John B.; Shaffer, H. Bradley (2010). "Turtles of the World 2010 Update: Annotated Checklist of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution and Conservation Status" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17.

- ^ a b van der Kuyl, Antoinette C.; Ballasina, Donato L. Ph. & Zorgdrager, Fokla (2005): Mitochondrial haplotype diversity in the tortoise species Testudo graeca from North Africa and the Middle East. BMC Evol. Biol. 5: 29. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-5-29 (HTML/PDF fulltext + supplementary material)

- ^ Fritz, Uwe; Kiroký, Pavel; Kami, Hajigholi & Wink, Michael (2005): Environmentally caused dwarfism or a valid species - Is Testudo weissingeri Bour, 1996 a distinct evolutionary lineage? New evidence from mitochondrial and nuclear genomic markers. Mol. Phyl. Evol. 37(2): 389–401. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.03.007