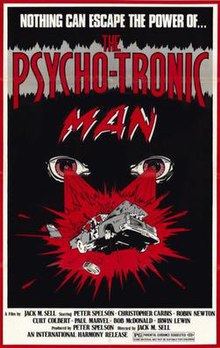

The Psychotronic Man

| The Psychotronic Man | |

|---|---|

Original poster | |

| Directed by | Jack M. Sell |

| Written by | Peter G. Spelson |

| Produced by | Peter G. Spelson |

| Starring | Peter G. Spelson |

| Cinematography | Jack M. Sell |

| Edited by | Jack M. Sell |

| Music by | Tommy Irons |

| Distributed by | International Harmony |

Release date |

|

Running time | 81 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $175,000[1] |

The Psychotronic Man is a 1980 American science fiction cult film[2][3] directed, shot and edited by Jack M. Sell, and written, produced and starred Peter G. Spelson. The film opened in Chicago at the Carnegie Theatre on April 23, 1980.

It is based on the obscure concept of psychotronics, which gained some prominence in the 1970s due to Cold War paranoia over mind control. The film inspired Michael J. Weldon to publish Psychotronic Video magazine, covering obscure films that he felt were under-appreciated by the mainstream.

Plot[edit]

Rocky Foscoe is a Chicago barber. One night he drives the long way home and, while parked on Old Orchard Road, has a nightmare in which his car is hovering in mid-air. The next day, he consults a doctor about his experience. He tries to return to work, but has an anxiety attack and flees, which worries his mistress.

He returns to the road to make sense of his experiences. An old man offers him help, and comments that strange things have been happening on that stretch of road; he himself had heard screams coming from the sky, implying that Rocky's car actually did float in the air. Soon afterwards, Rocky has another attack; in return, his host fires at him with a shotgun, and Rocky reacts by killing him with supernatural force.

Five hours later, Chicago police discover the body of the old man, and tire tracks from Rocky's car that suddenly stop, as if his car had floated into the air. That night, seeing an item in the newspaper about the old man's death on the road, the doctor connects Rocky with the killing and calls the police. Later, Rocky unexpectedly shows up, discovers the doctor's suspicion, and kills him with his psychic powers. When the police arrive, they surmise a supernatural explanation for the killing. The next day, they consult a professor at the Chicago Institute of Psychology, who explains his parapsychological theory that the killer has somehow tapped the latent power of his subconscious mind, which he refers to as "psychotronic energy".

Rocky visits his mistress and returns home. A confrontation with his wife grows out of hand, and he nearly kills her with his psychotronic powers.[4] The police, on stakeout outside his home, hear the scream and go in pursuit. Rocky drives downtown and manages to keep ahead of the police, at one point using his powers to float the car again. When he reaches a dead end, he crashes the vehicle and flees on foot. He takes the gun from an officer who has trapped him in a warehouse, then heads for the roof of a hotel, killing a security guard on the way. The pursuers catch up with him in a boiler room, but he psychotronically kills one of them (the officer he had taken the gun from earlier) and escapes to a tower in an adjoining building. The police, on the rooftop opposite, call in a SWAT team to shoot down Rocky.

As the SWAT team moves into position, a special intelligence agent appears and orders the police to capture Rocky alive, so his unique powers can be exploited for national security. The sheriff bluffs to Rocky that he has one last chance to surrender, then has him shot. Although he falls off the tower, his body is absent on the streets below. In the final shot, Rocky is back in the woods of Old Orchard Road.

Cast[edit]

- Peter Spelson as Rocky Foscoe

- Christopher Carbis as Lt. Walter O'Brien

- Curt Colbert as Sgt. Chuck Jackson

- Robin Newton as Kathy

- Jeff Caliendo as Officer Maloney

- Lindsey Novak as Mrs. Foscoe

- Irwin Lewin as Professor

- Corney Morgan as S.I.A. Agent Gorman

- Bob McDonald as Old Man

Production[edit]

- Direction – Jack M. Sell

- Assistant Director—Phil Lanier

- Producer – Peter Spelson

- Music – Tommy Irons

- Director of Cinematography – Jack M. Sell

- 2nd Camera—Phil Lanier

- Editing – Jack M. Sell

- Art Direction – Fred Becht

The Psychotronic Man was one of the few feature films to be shot entirely in Chicago since the days of the silent movie. It was also entirely produced outside any of the existing studio systems and financed by private funds.[5] At the time Chicago’s mayor Richard J. Daley actively discouraged movie making because he felt the movies that were being made at that time period were mostly negative and rebellious, and he wanted Chicago to be seen in a good light. As a result of this there were almost no permits issued to get scenes filmed. According to Peter Spelson's DVD commentary, this meant that all of the scenes including the downtown running gun battles and the high speed car chases with fake police cars were filmed illegally and without permission or prior notification.

Distribution[edit]

The film only played commercially once in Chicago, and was shown in the southern Drive-in theater circuit. In Europe, unauthorized copies of the film, often under different names, proliferated. One version of this went on to inspire the name of UK punk/hardcore band Revenge of the Psychotronic Man.

Reception[edit]

R.G. Young describes the movie in the Encyclopedia of Fantastic Film as a "minor thriller".[6] John Stanley's Creature Features is equally dismissive: "Slow-moving, ponderous independent feature ... with long stretches where very little happens."[7]

Film critic Michael J. Weldon later coined the term Psychotronic movie for a low budget genre B movie that is ignored or disdained by the mainstream. According to Weldon, "My original idea with that word is that it's a two-part word. 'Psycho' stands for the horror movies, and 'tronic' stands for the science fiction movies. I very quickly expanded the meaning of the word to include any kind of exploitation or B-movie."[8] The term gained popularity throughout the 1980s with Weldon publishing The Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film, The Psychotronic Video Guide, and Psychotronic Video magazine, and has subsequently been adopted by other critics and fans. Use of the term tends to emphasize a focus on and affection for those B movies that lend themselves to appreciation as camp.[9]

References[edit]

- ^ Steigerwald, Bill (1987-08-09). "X Doesn't Mark The Spot". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2017-05-18.

- ^ Barnes, Brad (2010-01-13). "Get ready for 'really good movies and really bad ones' at the Psychotronic Film Festival". Savannah Morning News. Retrieved 2015-10-21.

- ^ Douglas Deuchler (20 September 2006). Cicero Revisited. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-1-4396-1697-0.

Other films using Cicero locations include the lowbudget cult classic The Psychotronic Man (1979) and The Blues Brothers (1980).

- ^ Kehr, Dave (2009-08-07). "Grindhouse at Your House: 'Combat Shock' on DVD". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-05-08.

- ^ "The Psycho-Tronic Man". 2008-01-24. Archived from the original on 2006-07-06. Retrieved 2017-05-08.

- ^ Young, R.G. (2000). The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Film: Ali Baba to Zombies (Illustrated ed.). Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 505. ISBN 1-55783-269-2.

- ^ Stanley, John (2000). Creature Features: The Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror Movie Guide (illustrated, revised ed.). Berkley Boulevard Books. p. 418. ISBN 0-425-17517-0.

- ^ Ignizio, Bob (April 20, 2006). "The Psychotronic Man (interview with Michael Weldon)". Utter Trash. Archived from the original on September 11, 2006. Retrieved October 20, 2006.

- ^ See, e.g., Horror international. Steven Jay Schneider, Tony, January 11- Williams. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. 2005. pp. 2–5, 34–35, 50–53. ISBN 0-8143-3100-9. OCLC 56058097.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)