Talk:Tamraparni/draft

This article possibly contains original research. (July 2019) |

Tamraparni (Tamil/Sanskrit) is an ancient name of the river proximal to Tirunelveli of South India and Puttalam of North Western Sri Lanka and the name by which the entire island of Sri Lanka itself was known in the ancient world, with use dating to before the 6th century BC.[1] A toponym, the adjective "Tamraparniyan" is eponymous with the socio-economic and cultural history of this area and its people, centred in Sri Lanka and primarily connected by the Vedic- Siddhar sage Agastya, a highly influential linguist, medicine-maker and royal Hindu spiritual guru and poet established in proto era Sri Lanka, India and Indonesia. Movement of people across the Gulf of Mannar during the early Pandyan and Anuradhapura periods, between this Tirunelveli river of Pothigai, Kalputti of Puttalam, Northwest Sri Lanka, Manthai, Adam's Peak, Trincomalee of Northeast Sri Lanka and across the Indian Ocean via Java and Sumatra of Indonesia – in emulation of Agastya and his acolytes – led to the shared application of the name for the closely connected region and its Hindu-Buddhist culture, by the time of Vajrabodhi up until the late medieval period.[2] Demand for several of its native goods made Tamraparni a famous centre of global trade in the old world. The success of Tamraparniyan civilization is owed in large part to the impact of the Tamraparniyan sea route and this exchange is captured in literature and epigraphy from before the common era. Its legacy is observed most strikingly in the present day in philosophical and spiritual discourse, alchemy, astronomy, law, worship, architecture, the arts, jewellery and couture, place names, irrigation and agriculture, metallurgy, cuisine, language, script, science and medicinal practices of the region. This huge impact of Agastya's research, cultivation and teachings, earning him the title "Tamir Muni" – a godfather sage of Tamraparnism – has led traditions and lineages across the continent to claim descent from him, although his family and acolytes were some of the earliest architects of Hinduism in Sri Lanka. Robert Caldwell, who states "Tamraparni" to be Sri Lanka's oldest known historical name, dates Agastya to at least the 7th – 6th century BC based on the Pandyans rule over the region in the advent of Vijaya and Kuveni, with Buddhist, Vedic and Tamil literature dating him earlier, to the neolithic age. Tamraparniyan spirituality transformed societies across ancient India, to Greece in the west, China in the North to Indonesia in the East. Tamraparni is a rendering of the original Tamil name Tān Poruṇai of the Sangam period, "the cool toddy palm-wine" river.[3][4][5][6][7][8]

Etymology[edit]

A meaning for the term following its derivation became "copper-colored leaf", from the words Thamiram (copper/red) in Tamil/Sanskrit and parani meaning leaf/tree, translating to "river of red leaves".[2][9] According to the Tambraparni Mahatmyam, an ancient account of the river from its rise to its mouth, a string of red lotus flowers from sage Agastya at Agastya Malai, Pothigai hills, transformed itself into a damsel at the sight of Lord Siva, forming the river at the source and giving it its divine name.[10] At Pothigai, Agastya taught Tamil grammar that he had invented, and learned the Tamil language from the deities Siva, his son Murugan, and in some traditions, from the Mahayana Buddhist fusion deity of Siva-Vishnu, Avalokiteśvara.[11][12][13] The shrine to Agastya at the Pothigai hill source of the river is mentioned in both Ilango Adigal's Silappatikaram and Chithalai Chathanar's Manimekhalai epics.[14] Similarly, the Sanskrit plays Anargharāghava and Rajasekhara's Bālarāmāyaṇa of the ninth century refer to an ashram of Agastya on or near Adam's Peak of the Central Highlands of Sri Lanka, the tallest mountains in Sri Lanka, from whence the river Gona Nadi/Kala Oya flows into the Gulf of Mannar's Puttalam Lagoon, and mention the medical ashram of Kankuveli in Trincomalee.[15] Tamraparni as Sri Lanka is captured as early as in the Mahabharata, Chandraketugarh Kharosthi Brahmi inscriptions, Ashoka's Edicts, the Puranas and in the accounts of Onesicritus.[16][17][18][19] Other name derivations eventually applied to the entire island of Sri Lanka include the Pali term "Tambapanni", "Tamradvipa" of Sanskrit speakers and "Taprobana" and "Taprobane" of ancient Greek and Roman cartographers.[2][4][20] Etymologically related are the terms "Tamraparna" and "Tambarattha".[21][22] Tamraparni's trade with the kingdoms of the ancient Israelites, ancient Egyptians and Phoenician navies has led to more improbable etymological observations, including "Taph-porvan" in Hebrew/Arabic/Phoneician (golden coast) and "Topa-pwene" (Land of Topaz-pwene) in Egyptian.[23][24][25] Robert Knox reported from his 20 years of captivity on the island in the hills that "Tombrane" is a name of the Sri Lankan Tamil people for God in Tamil, which they often repeated as they lifted up their hands and faces towards Heaven".[26]

Geography[edit]

Present day Sri Lanka, the Tan Porunai river and Indonesia[edit]

Tamraparni is the oldest historical name of the island of Sri Lanka, called most frequently by this name in Hindu, Buddhist, Greek and Roman literature and the earliest world maps.[27] Many of these representations share geographical peculiarities of Sri Lanka, including place names, that have survived to the present age, however they attribute a much bigger landmass to Sri Lanka than exists today. A far narrower Gulf of Mannar is consistently indicated, and that Western Sri Lanka, particularly the Puttalam coast and the Kalputti islands through Kudiramalai up to Manthai shared a much closer land border to the mouth of the Tamraparni river (Tan Porunai or present day Thamirabharani river) of Tirunelveli, South India in the pre-classical era. "Tamraparni" has simultaneously been the name of this river that flowed near Sri Lanka, with the joint use of the name a result of movement of inhabitants during early Pandyan rule, particularly acolytes of their family priest and the head of their literary Sangam academies, Agastya, whose impact survives in Tamil Nadu, Sri Lanka, Indonesia and beyond. The region stretching south of the Tān Porunai river and Tirunelveli in Tamil Nadu – the citadel of the Pandyan kingdom – towards Sri Lanka, was referred to as Tamraparna by extension in the ancient period.[28][4][5][29][30][31] Settlements of Agastya-following early Velir-Perumakan populations of ancient Sri Lanka and ancient Tamil Nadu (in the river's valleys) have been excavated at megalithic urn burial with black and red ware sites at Pomparippu on the island's west coast (just south of Kudiramalai) and in Kathiraveli, on the island's east coast. Strongly resembling early Pandyan burials, some of these Tamraparniyan burial sites were established in the South Asian Iron Age up to the fifth century BCE.[32][33][34] The Annaicoddai seal with Tamil Brahmi and Indus Script reveals a clan-based settlement in the Jaffna region in the Iron Age.[35] The star Canopus is named Agastya in Vedic Hindu literature after the sage, related as both a person and a star, associated with the southern skies whose heliacal ascent marked the end of the rainy season, purification of water and the beginning of autumn. Canopus is described by Pliny the Elder and Solinus as the largest, brightest and only source of starlight for navigators near Tamraparni island during many nights.[36][37][38][39][40]

Brahmi inscriptions with Megalithic Graffiti Symbols from the Chandraketugarh archaeological site in North India read "yojanani setuvandhat arddhasatah dvipa tamraparni", meaning "The island of Tamraparni (now Sri Lanka) is at a distance of 50 yojanas or 50 km from Setuvandha (Rameswaram in Tamil Nadu).[41] In Valmiki's Ramayana, "Tamraparni" is related "Search the empire of the Andhras, the sister nations three, Cholas, Cheras and the Pandyas dwelling by the southern sea. Pass Kaveri's spreading waters, Malaya's mountains towering brave, seek the isle of Tamraparni, gemmed upon the ocean wave!"[42] Mahābhārata (3:88) written by Vyasa describes the island of Tamraparni below the country of the Pandyas and Kanyakumari and its most sacred Hindu pilgrimage sites.[43] "Tamraparni" is, according to 5th century legends of Mahavamsa and Dipavamsa, the name of the area invaded in Western Sri Lanka by the banished Vijaya of Vanga, bringing with him Pandyan queens.[20] Following his marriage to the Yakkha (Yaksha) queen Kuveni, the "lady of Tamraparni", he entered the royal house of Pandya through another marriage. The name Tamraparni, already in use by Tamil inhabitants of the island, matched the copper-bronze sands of red hues on the northwest Sri Lankan coast near Kudiramalai, and this was adopted in Pali as Tambapanni.[44] Later in 543 BC, the invaded island area was made Vijaya's capital that he called the Kingdom of Tambapanni, of a country north of the island, called Rajarata. The Kudiramalai coastal point on the Gulf of Mannar, near Chilaw/Mannar and north of Puttalam on the west coast is where it was established.[4][9] A Pali story of the Jataka tales from the same period renders Sri Lanka's name as "Tambapanni"; regions of Sri Lanka such as Nagadipa, Ratnadipa, Lankadipa, Giridipa, Ojadipa, Varadipa, Mandadipa and river Kalyani too are mentioned in various tales.[20] Sri Lanka suffered the 3rd century BC Indian Ocean tsunami on its western coast during the reign of Kelani Tissa who ruled at Kalyani c. 220 BCE. Kapilar and Nakkirar's text Purananuru too mention Tān Poruṇai river in the context of Lanka; in this literature corpus Lanka, a province of Tamilakam once lay close to the estuary of the river before this huge deluge separated Lanka with a broad channel from whence it has remained the island of Sri Lanka.[1][45] In fact, the thirteenth century Sri Lankan Tamil commentator and music theorist Atiyarkkunallar noted that centuries before this, the First Sangam took place in kadal kolla ppatta Maturai, the "Maturai that was flooded by the sea," a tsunami that had destroyed 49 provinces (nadu), mountains and rivers of the old Pandya land, prompting the Pandyans to conquer new lands.[46][47]

The Puranas mention Tamraparna/Tamraparni interchangeably as one of nine divisions of Bharatavarsha, the greater Indian subcontinent, and as the river sourced from the Kulacala hill of the Malaya mountains in the Pandyan country of Dravida, visited by Balarama, flowing through sandalwood regions, famous for pearls and counch, fit for Śrāddha offerings, sacred to Pitrs, where it flows towards the southern ocean, and at its confluence with the ocean, produces conches, shells and pearls.[48] In Vyasa's Sri Tambaravani Mahatmyam, the river is described as very holy to Hindus.[49] Kautilya in his Arthashastra describes the Tamraparni as “a large river, which went to meet and traverse the sea (samudram avaghat) containing the row of islands”.[50] The Vishnu Purana lists Tamraparni as being one of nine continents.[51] The name "Tamraparni" was adopted into Greek as Taprobana, called as such by Onesicritus and Megasthenes in the 4th century BC.[52] Megasthenes shares in Indica that "Taprobane" is separated from the mainland of South India by a river.[53] "Taprobane" was a new hemisphere according to Hipparchus, Strabo also mentions Taprobane, while fellow Roman writer Pliny the Elder states that only during Alexander the Great's rule did the west consider Taprobane to be an island.[54] Pliny the Elder described "Taprobane" as being another world called "Antichthonum", and known as the Taprobane continent down to his time, the "great southern land" that was the beginning of South East Asia before this "error in his interpretation" was corrected by ambassadors of Roman emperor Claudius, in that Taprobane was the island of Sri Lanka. Roman diplomats visited Tamraparni during the reign of Korran of Kudiramalai, and Chandramukha Siva and Damila Devi of Anuradhapura. The "arms and age of Alexander the Great were the first to give proof" Taprobane was Sri Lanka according to other scholars, which until then had been doubted by Solinus, Pomponius Mela and Hipparchus. In fact, Mela's world map of 43 CE depicts the island of Taprobane as a large island off the tip of South India, towards which the river "Tubero" flows. Pliny describes the island to have been twenty days sail from the country of the Prassi near the Ganges when performed in poorly-made Egyptian vessels made of papyrus, but reduced to seven days voyage in better constructed vessels.[55] Gaius Julius Solinus repeats that the Gulf of Mannar is a shallow sea, that the star Canopus shines brightest near Tamraparni and is the only star of use in navigation, that the moon was only visible for eight days out of sixteen, and because the sun rose on the right and set on the left, the course of vessels should be determined by the flight of birds.[56] Nearchus and Onesicritus, a contemporary of Alexander the Great who visited Sri Lanka, mention the island as "Taprobana", which also finds mention in De Mundo of Aristotle and in the world map of another of his students, Dicaearchus. One of the first Geographies in which it appears is that of Eratosthenes (276 to 196 BC) and was later adopted by Ptolemy (139 AD) in his geographical treatise to identify Sri Lanka as the relatively large island "Taprobane", south of continental Asia.[57][58][54] Also catalogued on his early map-treatise of Tamraparni island are the towns of Nagadiba Maagrammum (Jaffna), Nainativu islet, Manthai, Trincomalee, Adam's Peak and Kataragama. Ptolemy names the Pothigai mountain "Bettigo", from where three rivers rise, and one, "Solen", flows into the ocean near Sri Lanka.[59][60] Sri Lanka as Taprobane is on the map of Dionysius Periegetes, while it is called "Insula Taprobane" on the Tabula Peutingeriana Itinerarium near the most southern river of mainland South India. By Anglo-Saxon maps of the tenth century, Taprobane is called "Sabrobancubar", a large island to the south of India, while just before, in Alfred the Great's Saxon-English translation of Orosius, Sri Lanka is identified as Taprobana, the island southeast of Point Calimere.[61] By the late medieval age, cultural exchange with the islands of Indonesia – to the point of shared sovereignty – led many Arab writers such as Masudi and Al-Biruni and European writers to declare Sumatra as being "another Serendib", "another Ceylon", "Tamraparni Major" or "Taprobana Major". The 1417 CE Florentine Map of Palazzo Pitti names it the latter, while relating features of it that are more typical of Sri Lanka.[62]

Society and culture[edit]

Tamraparniyan royalty, economy and trade[edit]

A successful society built from strong spiritual values in governance, a lucrative Tamraparniyan economy and international trade culture ensured a reputation for the region as being a highly developed example and the richest of the old world. It was royal decree that underpinned governance of the region up until the medieval period with evidence of elections and councils. The earliest known royal influences in Tamraparni are that of the family members Kubera – the original ruler of Lanka, Pulastya, Agastya, Vishravas and Ravana, who feature in megalithic Pandyan era society. There were also other royal Tamraparniyan houses, related in large part to the Mūvēntar – the Three Crowned Kings, whose empires helped spread the culture. The Velir-Perumakan group (Perumakan being a lineage title of Velir chiefs meaning "great being, exalted one") formed an important segment of proto-historic Tamraparniyan society, having introduced the megalithic black and red ware techno-culture to Sri Lanka by the 6th century BC, giving leadership and direction to its subsistence economy.[67][68][69] The arrival of Bengali Hindus from North Indian kingdoms of Gangaridai led to more royal houses of Tamraparni. Different kingdoms functioned simultaneously through much of Tamraparni's history. Used from antiquity for agrarian purposes and determining the New Year, the Tamraparniyan calendar utilised lunisolar fractions from ancient Hindu traditions, when conceptual designs for date and time were similar across the subcontinent; the various ethnic groups' traditions employed Rāśi and the vernal equinox for annual determinations.[70]

Pre-modern coinage in Sri Lanka, archaeological ruins as well as the oldest confirmed inscriptions of the island, the Kandarodai Tamil Brahmi inscriptions and the Tissamaharama Tamil Brahmi inscription reveal the socio-cultural and economic diversity of the island from its north to south in antiquity. Some of the earliest Brahmi script inscriptions of the world have been found on potsherds in Anuradhapura and nearby Mihinthalai, published in 1996. Many of these types of inscriptions around the island refer to chiefs of the Velir-Perumakan group, donations of Brahmins and Buddhists, royals, and highlight diverse occupations including physicians and teachers (guru).[71][72][73][74] The establishment of these Tamraparniyan trade routes gave origin to several modern words, including those related to seafaring such as navy (நாவாய்–Nāvāy), catamaran (கட்டுமரம்–Kaṭṭumaram), and anchor (நங்கூரம்–Naṅkūram). The earliest reference of Tamraparniyan seafaring in Sri Lanka is attested in a 1st century BCE inscription on a boulder located at the Abhayagiri monastic complex in Anuradhapura, which says, "Dameda Navika Karavaha asane…", meaning that a Tamil Karaiyar navy captain was entitled to the seat of honour. Similarly, the Vellaveli Brahmi Inscription of Batticaloa details a Samadhi rock of a Perumaka Naval captain. Tamraparni's prized exports from antiquity were fruits, medicines, rice, honey, palm tree toddy wine, eye-cosmetics, ebony, fragrances, spices (cinnamon, cumin, cardamom, ginger, turmeric, black pepper, cloves), native metals such as wootz steel, copper, gold and silver, pearls, gemstones (sapphires, rubies, Cat's eye, aquamarine, jacinth, red and hessonite garnets, agates, amethyst, carnelian, tourmaline and topaz), skins, elephants, apes, peacocks, tortoise-shell and cotton. The main emporia were Gurunagar and Kadiramalai-Kandarodai, Jaffna in the north, Kudiramalai and Manthai in the North West, Galle and Godavaya in the South and Trincomalee in the East. The seafaring Tamils of the Jaffna port of Valvettithurai established trading contacts with the Coromandel Coast of South India, from places such as Point Calimere's Vedaranyam up to Myanmar and established cities such as Nagapattinam in South India which furthered their global trade.[75][76][77][78][79][80][81]

Elephants, gold, pearls and law[edit]

The eminent grammarian, mathematician and Vedic priest Kātyāyana describes the kingdoms of the Three Crowned Kings ruling the south in the 4th century BCE, extolling the heritage of the Pandyas and the sanctity of the Tamraparni rivers' waters and shrines.[82][83] At the Tamraparni river's mouth, Korkai, one of the Pandyan kingdom's early capitals and the epicentre of the pearl trade thrived. Referring to pearls, Kautilya in his Arthashastra speaks of many varieties such as "Pandya-Kavadaka" (of Kapatapuram) and "Thamro Par nika, that which is produced in the Tamraparni", notes the Pandya country is famed for its gems and pearls, and that three other kinds of gems/pearl – the Kauta, Maleyaka and Parasamudraka are found on Adam's Peak.[84][85][86] Varahamihira's Brihat Samhita mentions the river Tamraparni, pearls whereof are said to have been slightly copper-coloured or white and bright.[87] Ptolemy names the Pothigai mountain "Bettigo", from where three rivers rise; he uses the term "Solen" for the Tamraparni River in Tirunelveli – the Latin term for chank – in reference to its world-famous pearl fishing. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea adds that the northern part of the island Taprobane is a day's journey distant, producing pearls, transparent stones, cotton muslins, and tortoise-shell, while Megasthenes shares in Indica that "Taprobane is separated from the mainland by a river; that the inhabitants are called Palaiogonoi, and that their country is more productive of gold and large pearls, and larger elephants, than India."[88][89][90][91][92] Kālidāsa in Raghuvaṃśa praises the pearl fisheries at the mouth of the river Tamraparni, while giving details that the Ikshvaku king Raghu had conquered the Pandyas by carrying successful arms up to the mouth of the river, and was gifted with these pearls.[93] The linguist Jules Bloch states that Tamraparni in this context was Sri Lanka, from whose coast the Pandyans paid Raghu the pearls.[94] The poem also relates Raghu's subsequent plans to attack the loka of Kubera's kingdom for his wealth following a request for education fees by a pupil, before Kubera "sent down a shower of gold coins" to stop the expedition.[95]

The northwest coast of Sri Lanka had an equally prospering pearl trade, overseen at Kalputti, Kudiramalai and the emporium Manthai. Connecting Manthai with Anuradhapura – another centre of early Tamraparniyan royalty and society – is the Aruvi Aru river, on which goods were transported. Before the advent of Vijaya, Kuveni and the Kingdom of Tambapanni, the west coast of Sri Lanka was where the Queen of Mannar and North Western Sri Lanka, Alli Arasani, the daughter of a Pandyan king, was paid tribute with pearls fished by Tamil Paravas at Kalputti (ancient Arasadi), detailed in Alliyarasaninataka and Alli Arasani Malai, which she used to trade Arabian horses, at Kudiramalai, before much of her land was lost in a great flood. She has been described as an "Amazonian" ruler, who had an administration and an army of only women, with males being their subordinates and servants.[96] Kuveni subsequently ruled from what remained of Alli Arasani's kingdom; ruins of her palace are in present-day Wilpattu National Park.[97][98][99] Megesthenes noted the southern Pandyan kingdom ruled by only women, whose queen was called "Pandaia, a daughter of Heracles".[100][101] Further excavations at the Chandraketugarh archaeological site in North India reveal the mast of a ship with Vijayasinha's seal, describing Vijayasinha, the son of the king of Sinhapura of Vanga's marriage to Kuveni – the indigenous "Yakkha queen of Tamraparni".[102] Pliny calls Kudiramalai the port "Hippuri" of Taprobanê. The island's Pandyan connection grew annually, as Vijaya sent his Pandyan father-in-law a large variety of beryls, chanks and pearls worth 2 lakhs as gifts, and princes of the dynasty such as Panduvasdeva and Pandukabhaya of Anuradhapura built reservoirs for irrigation on the island using ideas from people who built similar structures at Tirunelveli's Tamraparni river and Madurai's Vaigai River coasts.[9] Pandukhabaya developed the city of AnuraiGramam as his capital (modern day Anuradhapura and the "Anurogramu Regia" of Ptolemy), after the name of a minister who founded the village, his grandfather who lived there, and from the city's establishment on the Nakshatra auspicious asterism, Anurai.[103][104] Residences, suburbs, lakes, cemeteries and temples to different deities were built, becoming home to various communities.[105] As Megesthenes shared his observations, a section of the west gate of Anuradhapura was reserved by the king for the Greek community. From Anuradhapura, Pandukhabhaya built gardens with Kadamba flowers (Neolamarckia cadamba) along the Aruvi Aru river up to Manthai on the coast, its old name thus "Kadamba Nadi River".[106] Directly crossing the Palk Strait from its mouth, the Vaigai River flowed, with many varieties of plants on its banks, from Madurai, home to the famous Kadambavanam Meenakshi Temple (in the forest of Kadamba flowers), where the plant continues to have religious significance to Hindu deities.[107][108][109] Pandukhabhaya's son Mutasiva built the Mahāmēgha Gardens, full of fruits and flowers, in the city. It would come to house the world's oldest documented tree (Ficus Religiosa).[110][111] Puttalam served as a second capital to kings of the Jaffna kingdom, who directed their energies towards consolidating its economic potential by maximising revenue from a lucrative pearl fishing industry developed there.[112]

Valmiki's Yoga Vasistha reveals that soldiers from "Tamraparnaka-Gonarda" (Tamraparni's Trincomalee) fought in the Kalinga War, along with other tribes from cities of the island either conscripted or observing.[113] Maha Buddharaksita Sthavira's Rajavamsa-Pustaka, written and preserved at the Abhayagiri Vihara from 277 – 305 CE, means "A Book of Royal Dynasties", which gives an account of Sinhalese occupation of the island, and states that Elara of Anuradhapura, "the son of Maharista, succeeded his father as king of Tamraparni island and Pundra and reigned for forty four years." Early Kings of Anuradhapura such as Mutasiva, Mahasiva and Elara were described as Tamraparni island kings who also ruled the kingdoms of Pundra, Chola and Pandya as dependencies simultaneously. When losing the Pundra and Tamraparni thrones, they sought refuge by sea in Suvarnnapura (Sumatra) in the Malay peninsula, where they died, corroborating the extent of Tamraparniyan power across South East Asia in the classial period.[65][66] Elara's implementation of Manusmriti laws during his reign earned him the title Manu Needhi Cholan and a reputation across Tamraparni for being a fair and just king.[114] During the reign of Korran of Kudiramalai and Chandramukha Siva and Damila Devi of Anuradhapura, Pliny continues that Taprobane is "more productive of gold and pearls of great size than even India”, as well as having “elephants ... larger, and better adapted for warfare than those of India”. Silver and a "marble-like" tortoise-shell were prized, fruits were abundant and the people had more wealth than the Romans.[115] Following the landing on the island of the first Roman Annius Plocamus at Kudiramalai, four Tamraparniyan ambassadors were sent with envoy Rachias to Rome; this event is generally considered to mark the beginning of direct Tamraparniyan trade with Rome, which until then had occurred via Tamilakam while Greek trade had been more prominent with Tamraparni. The king who sent the mission ruled a town on the sea coast, and not the interior.[116] Coins of Plocamus have been excavated in Mannar.[117] By this stage, a gentle and discreet king without an heir was favoured. Thirty advisers to the king were elected by the people in elections, and a majority of this council was needed to pass sentencing, including capital punishment. A right of appeal process existed for the people, where a jury of seventy could be appointed, and if the accused were acquitted, the council of thirty were held in the "deepest disgrace."[118][119]

Citing Onesicritus, Pliny states tigers and elephants on the island were hunted for sport during his time – "the chase" being Tamraparni's main festival. Plocamus agreed, stating the Sri Lankan leopard and sea tortoises as well as fish were also hunted. Eratosthenes, Strabo and Ovid observed elephants in Tamraparni. The king of Taprobane sells elephants for their height, as opposed to for warfare (India) or their ivory (Africa) by the time of Cosmas Indicopleustes' accounts of Tamraparni. This notice of Tamraparniyan elephants is in strict accordance with that of Claudius Aelianus a few centuries earlier, who agreed with Pliny that Tamraparni also had pasturing grounds for numerous elephants of the "largest size.... more powerful and bigger than those of the mainland", and may be "judged naturally cleverer in every way". They were bred in ancient Sri Lanka and transported in large native vessels to the opposite continent, and sold to the king of Calingae. Aelian also reveals that those who lived on the coast were unaware of elephant hunting, which was carried out in the island's interior. The island had groves of palm-trees "wonderfully planted in lines, just as in luxurious parks, shady trees are planted by those in charge".[120] Ptolemy had captured these pastures of elephants on his map while Periegetes states "Taprobanen Aaianoram elephantam genitricein" meaning Tamraparni is the "mother of the Asian elephant".[121] Gaius Julius Solinus states that a river divided the island with half occupied by men and the other by beasts and Asia's largest elephants; Tamraparni is also abundantly stored with mother-pearls and all kinds of precious stones.[122] During the Kalabhra Interregnum, Ambrose, informed by Moses, the Bishop of Adulis, recalls to the writer Palladius of Galatia the voyage of the Bishop and an Egyptian Theban lawyer to South India; here the Great king of Taprobane island (which had four other princes) is represented as also being the Great King of the chiefs of India, who they obeyed as viceroys in satraps. One of these Indian Malabar sovereigns detained the lawyer for six years, and was subsequently flayed as punishment upon the Tamraparniyan king becoming aware of the lawyer's "Roman nobility", ordering the prisoner's release.[123] It was during the rule of the House of Lambakanna I in Anuradhapura that the party attempted to travel to Taprobane, who also shared that Tamraparni was so rich in magnetic rocks that ships made with nails could not depart from it, and instead were drawn back.[124][125] Taprobane's ten fortified cities are expanded upon in Jordanes' Getica, based on the accounts of Orosius.[126] In the Hereford Mappa Mundi of Haldingham in 1300 CE, Sri Lanka is the large island in the Indian Ocean "Tuphana", home to elephants and dragons.[127]

Gems, ebony and spices[edit]

On Tamraparni island, Agastya's hermitage near Adam's Peak in the Central Highlands of Sri Lanka was on Mount Vaidurya, made of precious stones, the Mahabharata notes, "propitious and illustrious" with abundant fruits, root and water.[43] "Vaidurya" is the etymological root word of "beryl".[128] Tourmaline descends from the Tamil/Sinhala word Toramalli meaning "something little out of the earth".[129] The Periplus states that, barring diamond, all other gemstones did not originate from India, but from Tamraparni.[130] Most of the Tamraparniyan gems formed the "Navaratnam", the nine sacred gems in the dharmic faiths, a very antique form of talisman present at the time of Gautama Buddha, that maintained through the ages the "Hindus' attitude towards life's enigmas". Each represents a celestial body and protects the wearer from its negative powers. These gems' roles in the traditional rituals, folk beliefs, and magical arts of Sri Lanka are well documented, it is a common male Tamil name and references to the symbolic art of navaratna occur in inscriptions of the 11th century on the island, enjoying wide popularity even today.[131] The inscribed 1st century BCE- 1st century CE amphora fragment in Tamil Brahmi bearing the name of Chief Korran of Kudiramalai found at the Ptolemic-Roman settlement of Berenice Troglodytica, Egypt was accompanied by worked pieces of blue sapphire, as well as hundreds of Tamraparniyan beads, corundum, carnelian and agate, articles he also traded with the Phoenicians and Serica.[132][133][134][135][136] Yellow sapphires (pushparaja) were also a Tamraparniyan specialty. Padparadscha sapphires, a light medium toned, salmon pink-orange to orange-pink hued corundum, also originally found in Sri Lanka, were rare; the rarest of all is the totally natural variety.[137] The Sinhalese name is derived from the Sanskrit "padma raga", where padma means "lotus" and raga means "colour" - "a colour akin to the lotus flower" (Nelumbo nucifera).[138][139] Prase was rare but found amongst the pebbles of Trincomalee's shores. Many of its prized gems were mined in the ancient Ratnapuram and Matura regions before being shipped out via its ports; colourless varieties of zircon formed a popular substitute for diamonds, and are today globally known as the Matura Diamond, named after what is now Matara District of South Sri Lanka.[140] In Tamraparni's southeast, the Manikka Ganga ("Gem River") flows from Sivan Oli Pada Malai (Adam's Peak) passed Kataragama temple and into the Indian Ocean at Yala National Park, one of three highly holy and "meritorious streams" mentioned in the Dakshina Kailasa Maanmiam, home to many native gemstones and wildlife.[141][142][143] Ptolemy, Pliny and Megesthenes mention Tamraparni's precious stones, with Ptolemy highlighting beryls and hyacinths among its products.[144] According to Jean-Baptiste Tavernier of the 17th century, rubies and other coloured stones of the island came mostly from a river in the middle of the island that flowed from the mountains, and that locals would search the riverbeds for them about three months following a spring flood. He adds that the rubies of Sri Lanka were "lovelier" than those of Burma.[145]

French biblical scholar Samuel Bochart first suggested Taprobane, whose people were known for their gold, gems, pearl, ivory and peacock trade, for the ports of Ophir and Tarshish during King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba's reign, offering the etymological link "Taph-porvan", meaning "golden coast" in Hebrew. According to Bochart, Tarshish was Kudiramalai, where as Tennent points to its location being Galle on the southern coast.[146][147][148] Old Tamil words for ivory, apes, cotton cloth and peacocks that were imported by the Israelites via the navies of Tarshish and the Kingdom of Tyre are preserved in the Hebrew Bible. Much of the spices, gems and gold of Sheba were sourced from Tamraparni; in turn Solomon procured a Tamraparniyan ruby specifically to woo the Queen of Sheba.[149][150][151] Some descriptions relate the ground of Taprobane with the coat of the king of Tyre. Ancient Egyptians described the Land of Punt to be their ancestral homeland in the east and an island, with different locations of it discussed by modern historians; native scholars and others such as James Hornell, Swami Vivekananda and A. C. Das identify it as the early Pandyans, having migrated into the Nile valley with their culture.[152][153][154][155][156] The earliest Egyptian records reveal the Pharaoh Sahure sent ships to Punt, returning with cargoes of antyue and Puntites. In Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor, a 12th dynasty ancient Egyptian story, the Land of Punt is an island, where the Chief of Punt is a Serpent, identified as an early Tamraparniyan Naga king, sending the sailor back to Egypt with gold, spices, incense, elephant's tusks and precious animals.[157] Pomparippu, Gurunagar and Kadiramalai-Kandarodai were points of cultural exchange with ancient Egypt.[158][159][160] Diospyros ebenum (Karangali), also known as True Ebony or Ceylon Ebony, native to Sri Lanka, was another celebrated Tamraparniyan export, cultivated in large quantities near Trincomalee, specimens of which have been found in Fifth Dynasty of Egypt-era arrow heads there. Producing the valuable and best-quality black wood to traders such as the Phoenicians up to the modern era, international trade of it is now banned from India and Sri Lanka due to threat of extinction.[161][162][163][164][165][166][167] Pharaoh Hatshepsut continued ancient Egypt's trade with the kingdom of Punt, her artists revealing much about the royals, inhabitants, habitation and variety of trees on the island, revealing it as the "Land of the Gods, a region far to the east in the direction of the sunrise, blessed with products for religious purposes", where traders returned with gold, ivory, ebony, incense, aromatic resins, animal skins, live animals, eye-makeup cosmetics, fragrant woods, and cinnamon.[168][169][170] Trade from Punt expanded until Pharoah Rameses III, who received royal linen, precious stones and cinnamon.[171][172][173]

Cinnamon is also mentioned in Hebrew texts.[174][175] In his letters of 1515, reiterating Sri Lanka to be the Taprobane of antiquity, Andrea Corsali shares it is where topazes, hyacinths, rubies, sapphires, carbuncles, agates, garnet, beryls, pearls and cinnamon are "still present".[176][177] Cinnamomum verum is true cinnamon, native to Sri Lanka, and was sold to ancient Egyptians who used it as a perfuming agent during their embalming processes, and as a medical agent.[178][179] The source of cinnamomum verum was long kept secret by Persian, Arab and Phoenician traders in the ancient world to protect their monopoly on supply, however the Old Tamil name of the spice, Karuppa reached the ears of Ctesias in the fifth century BC who called it "Karpion" via Arabic in his Indica, praising the sweet scent of its oil.[180][181] During the Greco-Persian Wars, the Phonecians had confided to Herodotus that cinnamon came from the land where the deity "Dionysus" had been brought up, where oxen and great birds were common.[182][183] In turn, tax-free imports of horses into Tamraparni from Persia were observed centuries later by Indicopleustes.[184] Rome would also use cinnamon as an expensive flavouring agent.[185] Ptolemy and Pliny both list ginger as another high-value export of Tamraparni island, grown in Sri Lanka's interior. Ginger, like cinnamon and other Tamraparniyan spices, had reached the Greeks and Romans via Arabian traders before direct trade was established, and reached Indonesia and Austronesian people of the Pacific Islands about 3500 BCE via Trincomalee's port; its modern name deriving from the Old Tamil name ingiver, meaning "ginger rhizome root".[186][187][188] Burgeoning cultivation of cumin and turmeric caught trader interest and were also recognized domestically for their therapeutic value. Also native to Tamraparni and South India is Elettaria cardamomum and the closely related spice Elettaria ensal - varieties of cardamom noted as a Sri Lankan product by al-Idrisi - which have since been naturalised elsewhere - "Elattari" meaning "granules of leaf" in Tamil.[189][190][191] Long before the spice wars, Manthai was a classical age emporium and centre of the spice trade, bartering cinnamon, pepper and cloves as well as the gems of Sri Lanka, most of the semi-precious stones, Indo-Pacific beads of the region and ceramics; black pepper from 600 CE and the world's oldest cloves dating from 900 CE, shipped in from the Maluku Islands of Indonesia, were excavated in Manthai in 2010.[192][193][194]

Wootz steel, copper, wares and more gems[edit]

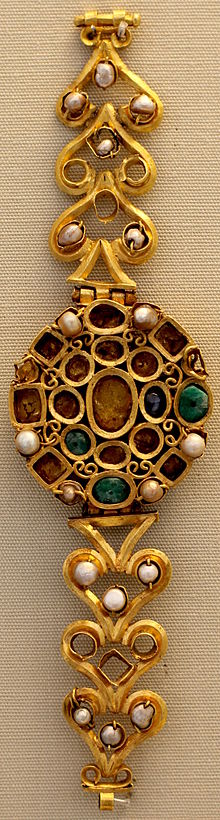

Shipping lanes between all major ports of Tamraparni and Tamilakam, South India were established. The region and citadel of "Nagadiva Maha Grammam" (the Nagadiba Maagrammum Regia of Ptolemy's Taprobana which is today the site of the Jaffna fort, Gurunagar of the Jaffna peninsula) was ruled by the Tamil minister Isikiraya under Vasabha of Anuradhapura around the time of the map's creation.[195] Jaffna's earliest settlers were in Gurunagar and Pattinathurai of Gurunagar, which features on the map, was a thriving port for foreign vessels. Excavations of black and red wares (1000BCE–100CE), grey wares (500BCE–200CE), Sasanian wares (200BCE–800CE), Yue green wares (800–900CE), Dusun stone wares (700–1100CE) and Ming Porcelains (1300–1600CE) conducted at the Jaffna fort reveals maritime trade between the Jaffna Peninsula and South Asia, Arabian Peninsula and the Far East during its Tamraparniyan floruit.[196][197] Similarly, 10km north of Gurunagar, at the megalithic trade centre and Naga capital of Jaffna Kadiramalai-Kandarodai, parallel inscriptions, coins, plaques and native ceramic Pre-rouletted and black-and red-wares from 1300 BCE show that the capital was well developed by the time of its mention by Ptolemy and the Periplus.[198][199][200][201][202] Various beads made of glass, ivory, chank, carnelian and marble, as well as copper kohl sticks were traded trans-oceanic from here under the kings Ko veta, Chadarasan and Ukkirasinghan.[203][204] Red coral had entered the Navaratnam talisman in India following what Pliny described as major demand for its spiritual significance; it was imported directly into Manthai following Roman-Tamraparniyan trade establishment, in exchange for the island's pearls, but may have reached Tamraparni earlier via the Greeks, Phoenicians and Israelites.[205][206][207] Thousands of Tamraparniyan gold, silver and red garnet shipments were made to the Anglo-Saxons between the 6th and 7th century – used for their military garments, as found in the Staffordshire Hoard and in Cloisonné jewellery such as the pendant of the Winfarthing Woman skeleton of Norfolk.[208][209][210] Tombs of Ming dynasty aristocrats have revealed gold bracelets and hairpins with a mix of Tamraparniyan sapphires, rubies and Sanskrit inscriptions, the focus of Yongle Emperor trade with Sri Lanka being the southern coast of Matura, featuring Galle and Tenavaram, as per the Galle Trilingual Inscription.[211][212][213] With base metals, copper mining was concentrated in Arippu and Seruvila, Trincomalee district, and may well have been exploited as early as 1800 BCE.[214][215][216] The port of Godavaya or "Goda Pavata Grama" at the mouth of the Walawe River flourished on the southern Tamraparni coast, serving Tissamaharama and Ridiyagama of the Ruhuna kingdom; it has been identified as the "Odoka" of Ptolemy's Tamraparni map.[217] Together with Gurunagar and Manthai, excavations at Godavaya have revealed more Sasanian and Chinese wares and pottery and that it was a crucial export point for Wootz steel-Seric iron (forged with Tamilakam iron and regional techniques in the sixth century BC at wind blast furnaces in Tissamaharama and Samanalawewa, shipped to Damascus, Rome, Egypt and China). Also sold were turtle shells and red garnets, carried down the Valavai Aru river. Tamraparniyan wootz steel was highly valued. Thousands of Roman coins were found there, confirming a direct shipping lane to Kodumanal in Tamil Nadu.[218][219] Further searches have led to the oldest cargo shipwreck in the Indian Ocean, just off the shore – the Godavaya shipwreck, dated from the third century BCE to 1st century CE. Its contents – including ceramics, stone querns, blue-green and black Alagankulam glass ingots, iron and copper works, black and red ware, metal spear, grinding stone and bench-shaped stone inscriptions with Pandyan Shiva-Vishna symbolism (the double fish, Nandipada bull footprint and Shrivatsa) – confirm early historic maritime trade between Southern Tamraparni and the Tamil Nadu coast.[220][221][222]

More features in post classical history[edit]

Sri Lanka has had many other names throughout its history, most of them identifying its royal, cultural and economic character. In Manimekhalai, smaller islands of North Sri Lanka are identified, and the term "Ratnadipa" or "Jewel Island" is used as an alternative to "Tamraparni", for Sri Lanka's main island. The name "Eelam" (homeland, gold, a synonym for Porunai meaning toddy wine in Tamil) remained in early classical use in Tamilakam, alongside the Tamil-Sanskritized "Tamraparni" (copper-coloured), "Lanka" (glittering in Tamil, distant island in the Mundari language), Serentivu (Island of Cheras in Tamil), "Simhala" (Kingdom of Lions in Sanskrit, Pali) and "Parasamudra" (Beyond the Sea in Sanskrit) as the name of Sri Lanka.[223][224][225] The anklets of the protagonists Kannagi-Pattini and Queen Kopperundevi in Silappatikaram, during the reign of Nedunjeliyan I, contain rubies and pearls respectively; traditions since describe that the ruby anklet was retrieved (by either Gajabahu I of Anuradhapura or three sisters from Kerala en route to Karaitivu (Ampara)) and consecrated at the Kannagi-Pattani Amman Kovil of Vattappalai, Mullaitivu.[226][227][228] In Book of the Later Han, during trade with Emperor Ping of Han in China, Tamraparni, a state south of India, is called "Yibucheng".[229] According to a third century Chinese source, the King of Tamraparni donated gemstones to the temples of the gods of India. The Veddha tribesmen sold gems and pearls for marked prices in Anuradhapura, according to Faxian in the fourth century, who witnessed one Buddhist monastery full of gems and pearls that the king was tempted to take them by force, further that gem traders visited Sri Lanka before the time of Buddha.[230][231] Cosmas Indicopleustes states in his account that by his time, the island went by the name "Sielediba" to the Indians, but remained "Taprobanê" to the Pagans, where hyacinth is to be found, including a famed fiery-red, large one atop a prominent temple of the island. Xuanzang also mentions this gem a few decades later. With the Kalabhra interregnum causing the temporary collapse of the Three Crowned kingdoms, trade continued between Taprobanê and Malé, Sindhu, China and Ethiopia-Eritrea (the Kingdom of Aksum) during Indicopleustes' time, as it did with the Himyarite Kingdom of ancient Yemen; the Yemeni trading alliance continued through to the reign of Jaffna's Martanda Cinkaiariyan.[232][233][234] Sambandar also mentions towards the end of the interregnum that the rearing waters of the sea surrounding Koneswaram temple of Trincomalee scatter on the shore "sandalwood, ahil, gold, precious stones and pearls – all of value high", for where Siva settled in his Tevaram.[235] When the Venetian Marco Polo eventually visited Sri Lanka, it was called "Seilan", and the king was Savakanmaindan, a Javaka royal from Java; its fame for its gemstones as well as its toddy palm tree wine had not diminished. Rubies were found there "like no other", alongside sapphires and topazes and amethysts. Polo continued that Savakanmaindan possessed a ruby which was "the finest and biggest in the world...about a palm in length, and as thick as a man's arm, the most resplendent object upon earth; quite free from flaw and as red as fire." Its value was so great that Kublai Khan of the Mongol Empire had even sent an embassy and begged the King as a favour to sell him this ruby, offering the ransom of a city. But the King replied that on no account whatever would he sell it, "for it had come to him from his ancestors".[236] Also using Sri Lanka's name to the late Romans, Persians and other Middle Easterners – "Serendib" – the Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta visited the Tenavaram temple in the 14th century and described the deity Dinawar as sharing the same name as the flourishing trade town in which He resided, made of gold and the size of a man with two large rubies as eyes "that lit up like lanterns during the night."[237][238]

The early Chera dynasty, based in Kerala near Agastya mala at the Tan Porunai river's source and in Sri Lanka, were another major trading power of the region. Residents of Kerala alongside the Pandyans were known to be disciples of Agastya.[239] In fact the Tamraparniyan Naga tribe was known by the Dravidian term "Cheran".[240] Korran of Kudiramalai had Chera alliances.[241][242] Malayali folk songs and legends emphasise that the Ezhava-Channars in Kerala descend from ancient Tamraparni, being the progeny of four bachelors of the king of the island sent to Chera king Bhaskara Ravi Varman of Kerala in the first century C.E. with coconut saplings, to setup coconut-farming and toddy tapping there. Some of them were Buddhist.[243][244] In another story, the Tamraparniyan king sent to Kerala eight martial families to quell a civil war that had erupted against the Keralan royal.[245] The Kuruntokai mentions that the Chera king Senkuttuvan hailed from Manthai.[246] His consecration of the Pattini-Devale of Manthai - a temple to Kannagi-Pattini was attended by Gajabahu I.[247][248] In the grammar anthology Tolkāppiyam, the Chera king Yanaikatchai Mantaran Cheral Irumporai, a contemporary of Pandyan king Nedunjeliyan II is mentioned in an honour of the Lord of the river Tān Poruṇai thus, "Vitar-c-cilai poritta ventan vali, Pun-tan porunai-p-poraiyan vali, Mantaran ceral mannavan vali", meaning "Long live the king who engraved in the hill, Long live the lord of the river Porunai filled with flowers and cool water, Long live the King Mantaran Chera".[249] This Chera presence culminated in the cognate descriptions of Tamraparni island as "Seralamtivu" or "Serentivu" (Island of Cheras), which is the term the Roman-Greek general Ammianus Marcellinus used (Serendivis) when noting the island's diplomatic relations with Julian, and it led to the eventual establishment of the Kingdom of Kotte by the Chera's descendants from Vanchi.[250][251] A temple of Western Sri Lanka claimed a stake in the Kerala Padmanabhaswamy Temple treasure discovered in 2011 in its vaults, saying its assets were moved to the Kerala temple after a Portuguese governor made an attempt to loot its wealth. The discovery of the treasure attracted widespread national and international media attention, being the largest collection find of gold and precious stones in the recorded history of the world.[252][253][254][255][256]

Food, drink and medicine[edit]

Much of Tamraparniyan cuisine and medicine survives today in Sri Lankan cuisine and Sri Lankan medicine. Joining cinnamon, ginger, turmeric, cumin and cloves on the Silk Road was the sale of Tamraparni's cardamom. These spices were not only recognised and used locally for flavour but also for their therapeutic value. The establishment and popularity of the traditional medicine system of Sri Lanka using such ingredients was independent of its commercial exchanges and has been preserved at a local level to the present day. It has four domains with much overlap – Ayurveda, Siddha, Unani and Deshiya Chikitsa, which have survived to the present day.[257] These have helped shape the diet and health practices since that era across South East Asia, and some of these traditions were evaluated at length in literature of the third Sangam.[258] At Kankuveli, a suburb of Trincomalee, Agastya and his disciple Trnasomagni established one of Asia's oldest and most influential medical universities that became dedicated to Siddhar spiritual practice at this ashram, the “Agathiyar Thapanam”, ruins of which were discovered in the 20th century.[259] Pliny observed Tamraparniyans commonly living to 100 years old, and noted the abundance of fruit on the island.[260] The historian Diodorus Siculus repeats that Tamraparni's inhabitants are distinguished by their "extreme" longevity and freedom from disease.[261] Ptolemy names rice, honey and ginger as being staples of the Tamraparniyan diet. In Uruttirangannanar's Paṭṭiṉappālai, the island's Eelam is described.[223] Aelian reveals that coastal Tamraparniyans devoted themselves to catching fish and "sea-monsters, for they asserted that the sea which surrounded the circuit of their island breeds a multitude past numbering of fishes and monsters."[262] In the writings of Ambrose in the fourth century, Tamraparniyans are described as living chiefly off milk, rice and fruits, which the country produced in abundance.[263] He also describes the preference of eating mutton in Taprobane. These observations are repeated by Palladius of Galatia, who calls Tamraparniyans "Makrobioi" – the "long-lived" – due to the excellence of the climate and the unfathomable judgement of God.[264][265][266] Endemic plants such as Avārai/Avāram, also known as the Matura tea tree bamboo, leaves and roots were used not only in the native production of Tamraparniyan wootz steel, but also for dyeing goat/sheep skins and in the Siddha treatment of many ailments.[267][268][269][270] The young buds, leaves and flowers of Tamraparniyan ebony were used by the natives in cases of flux and liver inflammation.[271] The culmination of Tamraparniyan medicine in all its different branches was the medical work Cekaraca Cekaram commissioned in the court of king Varodaya Cinkaiariyan, and another colossal work on medicine Pararaca Cekaram, named after the successor monarch Martanda Cinkaiariyan (Pararacacekaran III).[272] The naturalist William Turner notes that the plant Guaiacum sanctum, also known as holy wood or Diet woode, grows not in Europe but in India, Taprobane, Java and the Tivu islets of the ocean, and whose broth cures several harsh diseases, including French pox.[273]

Clothing attire, cosmetics and martial arts[edit]

With couture, wool and linen were not common in Tamraparni, but sheepskin was used to "wrap around their middle", which may have been the sarong – natively known as saram.[274] Centuries before Ambrose, Solinus notes that during Plocamus' arrival at Kudiramalai only the king wore the "Syrma", resembling "that of Bacchus."[275] Tamraparniyan men had the preference of wearing their hair long, giving them the appearance of women, according to Ptolemy. Men binding their hair in a bun or "Kondai", common in Tamilakam and Sri Lanka, is mentioned in Sangam literature as one type of hairstyle, and was usually held up with a tortoise-shell comb.[276][277] Eustathius of Thessalonica states that during Peregietes' time, Tamraparniyan men wore glittering jewels in the manner of women, and bound their long hair, in devotion to the deity Aphrodite Colias.[278] The binding of men's hair was also noted by Agathamerus, and continued to be observed on the island by Tennent. Solinus observed that dyeing the hair was common.[279] Cosmetic ingredients such as cinnamon bark and other spice components – used for fragrances – and copper kohl sticks – for eye makeup – were also exported from Pomparippu and Kadiramalai-Kandarodai to Rome and ancient Egypt.[280][281][282][283]

The classical era martial arts practices of Silambam and Kuttu Varisai (from Agastya and Murugan), Angampora and Kalaripayattu utilised weaponry, staffs and hand combat techniques alongside yoga, breathing exercises (pranayam) and meditation. Their spread and popularity in Indochina were due to spiritual links to Hindus and Buddhists, while the prized Silambam staff travelled with the Romans, Greeks and Egyptians to Europe, the Middle East and Africa.[284][285][286] On the south bank of Tamraparni river were the Tirunelveli Nadar-Shannars, a royal bow-men vassal, who like their related communities the Ezhava Channars and Tiyyas of Kerala, descend from Shandrar emigrants from Jaffna and other districts of Northern Sri Lanka, called "Ila-kulattu Shanar", in Sekkizhar's Periya Puranam.[287][288] Land deeds were granted to them by early Pandyan royals; Nadar tradition holds that these Tamils are heirs of the Pandyan kingdom. Migrating cyclically from the early classical rule of the Three Crowned Kings, their movement led to socio-economic exchange, with agricultural labourers (Nadar climber), aristocrats (the Nadan (Nadar subcaste)), Jaffna seednut palmyra and jaggery cultivators, toddy tappers and proponents of the Kalaripayattu Dravidian martial arts settling south of the river.[287] By the time of the Travancore kingdom, these Ila Nadar Shannars had setup headquarters at Agastheeswaram, Kanyakumari district, where their chieftain resided with special defences accorded by the king; this site had been visited by Agastya, where its medicinal herbs at Marunthuvazh Malai formed part of his research in the development of Siddhar medicine. The joint socio-cultural-political nexus of the region in the sixteenth century drew Achyuta Deva Raya, King of the Vijayanagara Empire of Karnataka to conquer Sri Lanka, win the Battle of Tamraparni against Travancore near the river, and marry the daughter of the Pandyan king.[289] By the advent of the Catalan Atlas as with many medieval European maps, "Taprobana" appeared with a set standard characteristics; two summers and two winters in each year, abundant fruit, elephants and wild beasts. The atlas shows an elephant and a black king, adding details about a race of "stupid black giants" who eat up white men "whenever they can get them."[290]

Arts[edit]

Poetry, music, dance and drama were favoured by Tamraparniyans. Native artistic tenets are preserved in extant Sri Lankan Tamil literature, as well as oral traditions, copperplate and stone inscriptions. The works of poets such as Eelattu Poothanthevanar from Manthai survived in Sangam literature, but much of the other literary works by Tamraparniyans were lost in destructions such as that of the Saraswathi Mahalayam library of Nallur.[291] Drumming music and dancing with a royal elephant parade greeted the Roman Sopatros on his visit to Tamraparni with Persians and Aksum Ethiopians from Adulis.[292][293] Batticaloan Tamil and Kandyan traditions of dance and drumming were markedly similar. Dances of Sri Lanka such as Kandyan dance were popular in the interior. Koothu dance and Terukkuttu theatre plays were popular in Jaffna and in the Batticaloa Territory; the historian and Professor K. Sivathamby, describing many dramatic and dance types in ancient Tamraparni, notes the ritualistic, tribal and religious origins of Tamil and Sinhalese theatrical art from the Sangam period, whose features have survived to the present day.[294] Bharatanatyam temple dancing and singing by Hindu women was observed at Tenavaram by Ibn Battuta during Martanda Cinkaiariyan's reign.[295][296] Pann melodic modes were usually employed in music, as per the Silappatikaram. The Sri Lankan Tamil musician Atiyarkkunallar - a minister of king Gunabhooshana Cinkaiariyan of Jaffna - wrote an Alagu System of music in the thirteenth century, capturing the possibility of linear, triangular, and quadrangular projections of the musical scale, while also mentioning the 10th century Tamil treatise on musical theory, Pancha Marapu. His work would go onto influence classical music such as Carnatic music in South India.[297][298][299]

Religion and spirituality[edit]

"Listen as I now recount the isle of Tamraparni below Pandya-desa and KanyaKumari, gemmed upon the ocean. The gods underwent austerities there, in a desire to attain greatness. In that region also is the lake of Gokarna...Pulastya said... Then one should go to Gokarna, renowned in the three worlds. O Indra among kings! It is in the middle of the ocean and is worshipped by all the worlds. Brahma, the Devas, the rishis, the ascetics, the bhutas (spirits or ghosts), the yakshas, the pishachas, the kinnaras, the great nagas, the siddhas, the charanas, the gandharvas, humans, the pannagas, rivers, ocean and mountains worship Uma's consort there". Mahabharata. Volume 3. pp. 46–47, 99.

Vyasa, Mahabharata. c.401 BCE on Trincomalee Koneswaram of Tamraparni island.[43]

The culture of Tamraparni was dominated by religion. Belief in the divine was ingrained in ancient Tamraparniyan civilization from its inception, where the ancient clans of Lanka such as the Yakkha believed in spirits and the Naga-Nayanar worshipped serpents. Royal rule was based on the divine right of kings. Because of this, the holiest sites of many faiths found in Sri Lanka have pre-historic tribal origins, with all of Tamraparniyan cities, society and history developing from sacred villages and towns in antiquity. Common Tamraparniyans, in their agricultural life patterns, depended upon the sun, moon, planets, stars, spirits of the dead and demons (to eschew them), animals, mountains, lakes and rivers in their livelihood, these aspects taking on divine status in their society. In this context, Sivan Oli Pada Malai (Adam's Peak) and Koneswaram of Trincomalee became majorly significant centres of faith from the Yakkha period, being sites of sacrificial and other cult practices, and have since had a global influence on worship; on Trincomalee, Charles Pridham, Jonathan Forbes and George Turnour state that it is probable there is no more ancient form of worship existing in the world than that of Siva Ishwara upon his sacred promontory.[300] The advent of outside influences about 2500 years ago caused suspicious association, with positive as well as negative depictions in different accounts, before a broader assimilation began of faith practices. The religion of Tamraparni thus became fluid, syncretic and by later standards, unorthodox. The initial development of Anuradhapura centralized Hindu and Buddhist worship while supporting cultural exchange on the Tamraparniyan sea route, helping leave a lasting global legacy. Towards its later periods, there was a continuation of religious trends in the third Sangam era where various Hindu (Saivite, and Vaishanava), Buddhist and Jain schools grew with native folk and animist traditions featuring Gramadevata, the village deities of Sri Lankan Tamil and Sinhalese people. Even today, the Sri Lankan culture has some elements that originated from the culture of the Yakkha and Naga, Raksha and Deva groups native to Tamraparni.[301][302][303][304][305]

Hinduism[edit]

The city of Trincomalee is uniquely a Pancha Ishwaram, a Paadal Petra Sthalam, a Maha Shakti Peetha and Murugan Tiruppadai of Sri Lanka; its sacred status to devotees of many Hindu deities led to it being declared "Dakshina-Then Kailasam" or "Mount Kailash of the South" and the "Rome of the Pagans of the Orient". Siva is the temple's chief dedication. All towns of the Pancha Ishwarams – Manthai, Munneswaram, Tenavaram, Trincomalee and Naguleswaram are depicted on Ptolemy's map of Taprobane, alongside the other prolific Murugan Tiruppadai of Sri Lanka, Kataragama temple. Temples sacred to the moon are found on Tamraparni's southern coast in his map treatise. At least two of the Murugan Tiruppadai Kovils – Koneswaram temple and Kataragama are highlighted in classical era scripture. Agastya is associated with and the name of the star Canopus in Vedic literature, where the star is the "cleanser of waters", and its rising coincides with the calming of the waters of the Indian Ocean; Pliny states that Canopus is large and bright on the island, providing light to the Tamraparniyans at night.[306][307] Thaipoosam, an ancient festival and national holiday in Sri Lanka celebrated on the full moon in the Tamil month of Thai (January/February), is when devotees believe Murugan received the Vel from his mother on his birthday, and is when the moon enters the lunar mansion or star cluster constellation of Pushya ("Poosam" in Tamil, "Pooyam" in Malayalam) shining brightest and on the ascendent. This Pushya star Nakshatra asterism is also ruled by the planet Saturn, has the blue sapphire (neelam mani) gem birthstone, the white pearl based on Rāśi, and is the best time for buying gold, learning from a guru, and collecting and administering Ayurveda and Siddha medicinal herbs.[308][309][310][311][312]

Adam's Peak, or "Sivan Oli Pada Malai" in Tamil (Siva's One Foot Mountain) features as "Uli Pada" of the Malea mountain range on Ptolemy's Taprobana map, and features a large footprint in a shrine that Hindus believe is that of the god Shiva. In Vyasa's Mahābhārata (3:88), a Sanskrit passage on the words of Saptarishi Pulastya (Visravas and Agastya's father) relates to the island and Hindu worship at the Koneswaram temple, describing indigenous and continental pilgrims across the island, including the shrine, before the Anuradhapura period. "Listen, O son of Kunti, I shall now describe Tamraparni. In that asylum the gods had undergone penances impelled by the desire of obtaining salvation. In that region also is the lake of Gokarna, celebrated over the three worlds...".[43] This literature elaborates on the two ashrams of the Siddhar Agastya on Tamraparni island – one near Trincomalee bay (now located at Kankuveli) and another atop the Malaya mountain range (that situated near Adam's Peak).[43][313] The Dakshina Kailasa Maanmiam details one of Agastya's routes, from the Vedaranyam forests of Point Calimere to the now ruined Tirukarasai Parameswara Siva temple on the banks of the Mahaveli Ganga river, then to Koneswaram, then Ketheeswaram of Manthai to worship, before finally settling at Pothigai. The Siva-worshipping Siddhar Patanjali's birth in Trincomalee and Agastya's presence points to Yoga Sun Salutation originating on the sacred promontory of the city.[314][315][316][317] The Tamraparniyan sea route was adopted by the Siddhar alchemist Bogar in his travels from South India to China via Sri Lanka; a disciple of Agastya's teachings, Bogar himself taught meditation, alchemy, yantric designs and Kriya yoga at the Kataragama Murugan shrine in the third century CE, inscribing a yantric geometric design etched onto a metallic plate and installing it at the sanctum sanctorum of the Kataragama complex.[318][319] Punch-marked coins from 500 BCE discovered beneath a temple in Kadiramalai-Kandarodai bear the image of the deity Lakshmi.[320][321][322] The inscriptions and ruins of Kankuveli alongside Vyasa's Mahabharata reveal the umbilical relationship of Kankuveli's Agastya ashram with the Siva temple of Koneswaram and his father Pulastya, relating its high sanctity and popularity with Tamraparni's natives. In fact, the Matsya Purana describes Agastya as a native of Sri Lanka.[323]

These Hindu features were often described by their Hellenistic/Roman counterparts in early Western accounts. Pliny the Elder confirms that even by his time, inhabitants of Taprobane island worship "Hercules and whose King dresses like father Bacchus".[54] The ocean around the sacred promontory of Trincomalee and Kataragama, Ptolemy describes, as being the "Sea of Dionysus", and the rocky promontory at the coast pointing into the ocean, "Dionysii promontorium", or "promontory of Dionysus" to Alexandrian mariners. Next to the city of Bacchus/Dionysus and elephant pastures resided the tribe of the "Nanigeri"/"Nageiri", the Nayanar-Nagas of the island.[324][325] In Geography of Avienus a Latin poem of Avienus written in 350 CE, based on Orbis descriptio by Alexandrian Greek poet Dionysius Periegetes (117—138 CE), the clause "Inde convenus ante promontoriam Auatrale, Confestim ad magnam Coliadis insulam perveneris, Taprobanen Aaianoram elephantam genitricein" is found, mentioning Tamraparni island being that of "Aphrodite Colias", whose inhabitants worship the "multi-towered temple to Venus on their rock promontory, phallic-shaped and located at the end of the island's Ganges river by the ocean." In a 12th-century commentary of Orbis descriptio, Eustathius of Thessalonica describes the Maha Shakthi Peetha temple of Koneswaram as the "Coliadis Veneris Templum, Taprobana."[326][327] By the time of Cosmas Indicopleustes, the merchant confirms that the island remained "Taprobanê" to the Pagans, but other names to communities of other beliefs; he continues that the natives and their two kings are heathens and on this island they have many temples.[328][329] Koneswaram of Trincomalee was described as the "Rome of the Pagans of the Orient" by the seventeenth century, before its destruction.[330] Furthermore, bronze sculptures of Agastya have been discovered from the 8th-9th century in Sumatra.[331] The Dinaya inscription of Central Java mentions King Gajayana consecrating an image of Agastya in a temple in 760 CE and that blessings should be showered on Agastya's descendents in Java. Agastya came to reside in Java, according to the Old Javanese Ramayana set before the rise of Hinduism in Indonesia in the first century CE, demonstrating a very ancient extension of the Tamraparniyan socio-political culture to Indonesia.[332]

A scion of one of Tamraparni's oldest Vaṃsa – Kubera (grandson of Pulastya, nephew of Agastya and son of Visravas) was the original and founding king of Lanka – a gold metropolis of Tamraparni and the capital of the Yaksha kingdom. Featured in the Puranas, Ramayana and Mahabharata, many ancient sculptures and other depictions of these figures adorn temples across Sri Lanka, famously at Isurumuniya in Anuradhapura where they once lived. Following the war and usurping of Lanka by his half-brother Ravana, Kubera moved to rule the city of Alaka in Sigiriya, Sri Lanka, where he was followed by Tamraparniyan natives including the Gandharvas, Yakshas and Yakshinis, Rakshasas, and Kinnaras.[citation needed] Archaeological excavations revealing the beginnings of the Iron Age in Sri Lanka have been found at Anuradhapura, where a large city–settlement was founded before 900 BCE. The settlement was about 15 hectares in 900 BCE, but by 700 BCE it had expanded to 50 hectares, while a similar site from the same period has also been discovered near Aligala in Sigiriya. Radiocarbon dating increasingly matches the lower boundary of the protohistoric Early Iron Age in Tamraparni island to match that of South India, at least as early as 1200 BCE.[333][334] In Hindu tradition, following the defeat of Ravana, Kubera is at this point elevated to divine status and worshipped as the God of wealth and comes to reside in Mount Kailash of Tibet. He is regarded as the regent of the North (Dik-pala), and a protector of the world (Lokapala).[335] The Tamraparni river is one of the beautiful sights a messenger will see in Kalidasa's Meghadūta, a story of one of Kubera's exiled Yaksha servants sending a message back to his wife in Alaka. This story's Yaksha figures feature on the entrances of many ancient buildings in Sri Lanka and has since spawned many inspired naratives of the "Sandesha Kavya" genre, including the Kokila Sandeśa, the Hamsa-Sandesha and the Haṃsadūta.[336][337]

Several shrines to Agastya exist along the banks of the river Tamraparni, as does the Kubera Theertham. In Vyasa's Tambaravani Mahatmayam, the holiness of the river is shared with the Sanskrit shloka Smaraṇāt darśanāt dhyānāt snānāt pānādapi dhruvam, Karmavicchedinī sarvajantūnāṃ mokṣhadāyinī meaning "Tamraparni is the river, which destroys the karmas of all living beings, who think of her, who see her, who meditate on her, who take bath in and who drink her waters. She bestows even Moksha on them". The river is described as a daughter of Agastya, and who is married to Samudra-Raja, the sea king, where she meets the ocean. One Hindu story on the river's origin was that a garland handed lovingly by Adi Parashakti to Parvati at the time of her marriage with Siva was in turn given by Parvati to Siva. When Siva, after wearing the garland, handed it to sage Agastya, it turned instantly into a beautiful, well-decorated maiden. Tamiraparani, meaning maiden shining like copper, was the name the Devas gave her. As instructed by Siva, Agastya proceeded Southwards for a balance of populations across the subcontinent, accompanied by his wife Lopamudra and Tamiraparani, and reached Malaya Parvata. The king of this range Malayeswara was only too happy to accept Tamiraparani as his daughter. Alwarthirunagari Temple on Tan Porunai's bank is the seat of Adi Parasakti. She bathed Devi Tamiraparani with sacred waters brought from the oceans and rivers, and got her married to Samudra Raja amidst great festivity. As instructed by Parasakti, Tamiraparani turned into a mighty river on that holy day of Thai Poosam. Agastya and others travelled in a special celestial vimana along the course of the river as she flowed and finally met her lover, the sea. In other traditions, the river was borne of a wish by Parvati to have a companion following the departure of the deities Ganesh and Murugan from the family home.[338] At the Tamraparni river's source in Tirunelveli, Tamil was created by Agastya, according to Kamban and Villiputturar, while Kancipuranam and Tiruvilaiyatarpuranam detail that Siva taught Agastya Tamil there.[339] Tamil Hindu tradition holds that the deities Siva and Murugan taught Agastya the Tamil language, who then constructed a Tamil grammar – Agattiyam – at Pothigai mountains.[11][12][13]

The Nava Tirupathi are a set of nine ancient Hindu temples dedicated to the deity Lord Vishnu, all on the banks of the river. Epigraphical references to the land next to the Tān-Poruṇdam river and the ownership of this land by respective temples on its banks are frequent from the medieval period. The inscriptions of the Chola temple Tiruvāliśvaram near Tirunelveli, found on the south wall of the mandapa in front of the temple's central shrine, identify the Tamraparni river with its original name Tān-Poruṇdam, describing the use of water from the TānPoruṇdam river to bathe the temple's god on Sundays following a gift.[340] The Mannarkovil inscription of Jatavarman Sundara Chola Pandyadeva relates the sale of land in Tamil Nadu near the river TānPoruṇdam to the Vishnu temple Rajagopalakrishnaswamy Kulasekara Perumal Kovil, in the vicinity of Rajendra Vinnagaram, and the Tirunelveli inscription of King Maravarman Sundara Pandyan II details village zones with TānPoruṇdam river as their boundaries.[341][342] A Sannyasin repaired and reconsecrated the Tentiruvengadamudaiya Emperuman Shrine between 1398–99 AD at the Pavanasini Tirtha on the TānPoruṇdam river.[343] The Bengali poet Krishnadasa Kaviraja mentions in Chaitanya Charitamrita the Tamraparni river in Tirunelveli, Pandya Desa, as a holy place Chaitanya Mahaprabhu visited as a pilgrim, and glorifies the Vishnu temple Alwarthirunagari Temple on its bank. The renowned Hindu yogi, medic and guru Sivananda Saraswati was born on the banks of the river.[344] An annual Pushkaram takes place for the river in the middle of October. The temple theerthams are the holy Tamraparni River and the Kubera theertham.[345]

Buddhism and Jainism[edit]

The Buddha, according to the Mahavamsa, made three visits to Tamraparni, stopping at Nainativu and Kalyani. Both towns were strongholds of the Naga nation. On his second visit, the chronicle states he settled a dispute between the Naga kings Chulodara and Mahodara (uncle and nephew), over a gem set throne which he was then offered.[346][347] Buddhism was introduced to Tamraparni during the reign of Devanampiya Tissa of Anuradhapura and at this time, Tamraparni is mentioned as the name for Sri Lanka in the Edicts of Asoka, one of the areas of Buddhist proselytism in the 3rd century BCE, with the declaration "The conquest by Dharma has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred yojanas (5,400–9,600 km) away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni)." (Edicts of Ashoka, 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika).[348] This event was contemporaneous with the Third Buddhist Council and the rule during the Third Sangam of the Pandyan king Nedunjeliyan I of Tamilakam, an important character of the Silappatikaram which was set in the three capitals of the Muventar. The epic features many faiths including Buddhism being practiced in South India during this time. Soon after Buddhism's arrival in Tamraparni, the Manimekhalai, Purananuru and Mahavamsa capture the destruction caused by the 3rd century BC Indian Ocean tsunami, during which Kelani Tissa ruled Maya Rata from Kalyani and Kavan Tissa was in Ruhuna. This tsunami had destroyed the early Chola capital of Puhar, following which the Chola figures Sena and Guttika, as well as Elara came to rule the north of Tamraparni from Anuradhapura.

Kubera was incorporated into the Jain and Buddhist pantheons with the patronym Vaiśravaṇa (Sanskrit) / Vessavaṇa (Pali) / Vesamuni (Sinhala), meaning "Son of Vaisravas", and syncretised as one of the latter religion's Four Heavenly Kings.[20][349] In the Buddhist text Jataka-mala by Aryasura, about the Buddha's previous lives, Agastya is co-opted and included as an example of his predecessor in the seventh chapter. The Agastya-Jataka story is carved as a relief in the Ajanta Caves of Maharashtra and the Borobudur of Java, the world's largest early medieval era Mahayana Buddhist temple.[350][351] The Divyāvadāna or "Divine narratives" a Sanskrit anthology of Buddhist tales from the 2nd century, calls Sri Lanka "Tamradvipa" and gives an account of a merchant's son who met Yakkhinis, dressed like celestial nymphs (gandharva), in Sri Lanka.[20] The Valahassa Jataka relates the story of the arrival of five hundred shipwrecked merchants, from Varanasi, to the prosperous port town and Yakkha capital of Sirisavatthu in "Tambapannidipa", where the ancient Yakkha inhabitants were slaughtered by Vijaya and his followers.[352] In one Jain story of Yakkha king Kubera founding the city of Ayodhya in North India, diamonds, sapphires and Cat's eye are mentioned as the gems adorning it, with housepools evoking the beauty of Tamraparni, and that those who have seen its jewels in its palaces and markets source them to Adam's Peak.[353] These mentions corroborate writers of the period in relating Tambapanni island as a "fairyland" inhabited by Yakkhinis or "she demons" and the story of Kuveni.[20]

Agastya's shrine on Pothigai Hills at Tamraparni river's source is important in the context of the Hindu Ramayana according to the Manimekhalai, which is the first Tamil literature to mention Agastya, while simultaneously conceiving and anticipating South India (Tamilakam), Sri Lanka and Java as a single Buddhist religious landscape.[354] The author of the Silappatikaram, utilizing the word "Potiyil" for the hills, hails the southern breeze that emanates from the hills that blows over the kingdom of the Pandyans of Madurai and Korkai that own it. The Manimekhalai concurrently describes a river flowing on the slope of Pothigai mountains where Buddhist monks observed meditation.[355] Tamil Buddhist tradition which developed in Chola literature, such as in Buddamitra's Virasoliyam, states Agastya learnt Tamil from the Bodhisattva deity Avalokitesvara; the Chinese traveler Xuanzang had recorded the existence of a temple dedicated to Avalokitesvara at Pothigai hills (Tamraparni's source).[11][12] In fellow Sangam work Kuṟuntokai of the Eṭṭuttokai anthology, a Buddhist vihara under a Banyan tree is described at the top of Pothigai. A comment that God had disappeared from the mountain was found in Ahananuru, from whose inaccessible top the stream of clear waters flows down with noise in torrents, and the fact that old men assembled and played dice in the dilapidated temple is described in Purananuru.[356][357] A similar development concurrently occurred in Sri Lanka in the eighth century with the growth of Avalokitesvara worship at Thiriyai by Pallava merchants at a traditional Naga site of Murugan worship connected to Koneswaram of Trincomalee – the Thiruppugazh calls this place "Kanthathiri", the Sinhalese "Girihandu Seya" and Ptolemy calls it "Thalakori".[358][359][360][361][195] The Statue of Tara, a famous statue of Avalokiteswara's consort Tara of the same time period was discovered on the east coast between Trincomalee and Batticaloa.[362]