Surry Hills, New South Wales

| Surry Hills Sydney, New South Wales | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

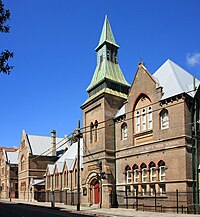

Surry Hills Library and Community Centre | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 33°53′10″S 151°12′40″E / 33.88611°S 151.21111°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 15,828 (SAL 2021)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 2010 | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 51 m (167 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 1.2 km2 (0.5 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | 1 km (1 mi) SE of Sydney central business district | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Sydney | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | |||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Sydney | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Surry Hills is an inner-east suburb of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Surry Hills is immediately south-east of the Sydney central business district in the local government area of the City of Sydney. Surry Hills is surrounded by the suburbs of Darlinghurst to the north, Chippendale and Haymarket to the west, Moore Park and Paddington to the east and Redfern to the south.[2] It is often colloquially referred to as "Surry".

It is bordered by Elizabeth Street and Chalmers Street to the west, Cleveland Street to the south, South Dowling Street to the east, and Oxford Street to the north. Crown Street is a main thoroughfare through the suburb with numerous restaurants, pubs and bars. Central is a locality in the north-west of the suburb around Central station. Prince Alfred Park is located nearby. Strawberry Hills is a locality around Cleveland and Elizabeth Streets and Brickfield Hill to the east of that.

A multicultural suburb, Surry Hills has had a long association with the Portuguese community of Sydney.[3]

History[edit]

The first land grants in Surry Hills were made in the 1790s. Major Joseph Foveaux received 105 acres (0.42 km2). His property was known as Surry Hills Farm, after the Surrey Hills in Surrey, England. Foveaux Street is named in his honour.[4] Commissary John Palmer received 90 acres (360,000 m2). He called the property George Farm and in 1800 Palmer also bought Foveaux's farm. In 1792, the boundaries of the Sydney Cove settlement were established between the head of Cockle Bay to the head of Woolloomooloo Bay. West of the boundary, which included present-day Surry Hills, was considered suitable for farming and was granted to military officers and free settlers.

After Palmer's political failures, his reduced financial circumstances forced the first subdivision and sale of his estate in 1814. Isaac Nichols bought Allotment 20, comprising over 6 acres (24,000 m2). Due to the hilly terrain, much of the suburb was considered remote and 'inhospitable'. In the early years of the nineteenth century the area around what is now Prince Alfred Park was undeveloped land known as the Government Paddocks or Cleveland Paddocks. A few villas were built in the suburb in the late 1820s. The suburb remained one of contrasts for much of the nineteenth century, with the homes of wealthy merchants mixed with that of the commercial and working classes.

In 1820, Governor Macquarie ordered the consecration of the Devonshire Street Cemetery. A brick wall was erected before any interments took place to enclose its 4 acres (16,000 m2). Within a four-year period the cemetery was expanded by the addition of 7 acres (28,000 m2) to its south. A road was formed along the southern boundary of the cemetery in the first half of the 1830s and was called Devonshire Street. The Devonshire Street Cemetery, where many of the early settlers were buried, was later moved to build the Sydney railway terminus. Central railway station was opened on 4 August 1906. The area around Cleveland and Elizabeth streets was known as Strawberry Hills. Strawberry Hills post office was located at this intersection for many years.[5]

In 1833, the Nichols estate was subdivided and sold. One purchase was by Thomas Broughton and subsequently acquired by George Hill who constructed Durham Hall on this and adjoining lots. Terrace houses and workers' cottages were built in Surry Hills from the 1850s. Light industry became established in the area, particularly in the rag trade (clothing industry). It became a working class suburb, predominately inhabited by Irish immigrants. The suburb developed a reputation for crime and vice. The Sydney underworld figure Kate Leigh (1881–1964), lived in Surry Hills for more than 80 years.

In 1896 Patineur Grotesque one of Australia's first films and first comedy routine filmed was shot in Prince Alfred Park by Marius Sestier.[6]

Surry Hills was favoured by newly arrived families after World War II when property values were low and accommodation was inexpensive. From the 1980s, the area was gentrified, with many of the area's older houses and building restored and many new upper middle-class residents enjoying the benefits of inner-city living. The suburb is now a haven for the upper middle class and young rich.[7]

Trams[edit]

The West Kensington via Surry Hills Line operated from 1881 down Crown Street as far as Cleveland Street as a steam tramway. It was extended to Phillip Street in 1909, Todman Avenue in 1912, and then to its final terminus down Todman Avenue in 1937. When the line was fully operational it branched from the tramlines in Oxford Street and proceeded down Crown Street to Cleveland Street in Surry Hills, then south along Baptist Street to Phillip Street, where it swung left into Crescent Street before running south along Dowling Street. It passed the Dowling Street Depot, then turned left into Todman Avenue, where it terminated at West Kensington. The line along Crown Street closed in 1957, the remainder stayed open until 1961 to allow access to Dowling Street Tram Depot. Transdev John Holland routes 301, 302 and 303 generally follow the route down Crown and Baptist Streets as far as Phillip Street.[8]

Urban character[edit]

Surry Hills has a mixture of residential, commercial and light industrial areas. It remains Sydney's main centre for fashion wholesale activities, particularly on the western side. The area is also home to a large LGBTQIA+ community, where Sydney's Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras (Pride Parade) takes place each year.

Surry Hills Markets are held in Shannon Reserve at the corner of Crown and Collins Streets, on the first Saturday of every month,[9] and the Surry Hills Festival is an annual community event, attracting tens of thousands of visitors, held in and around Ward Park, Shannon Reserve, Crown Street and Hill Street.[10] The Surry Hills Library and Community Centre sits opposite Shannon Reserve and houses the local branch of the city library and the Surry Hills Neighbourhood Centre.[11]

In popular culture[edit]

Literature[edit]

The Harp in the South is a novel by Ruth Park. Published in 1948, it portrays the life of a Catholic Irish-Australian family in Surry Hills, which was an inner city slum at the time. A sequel, Poor Man's Orange, was published in 1949.

Transport[edit]

Central railway station, the largest station on the Sydney Trains and NSW TrainLink networks, sits on the western edge of Surry Hills. Surry Hills is also serviced by Transdev John Holland and Transit Systems buses. The Eastern Distributor is a major road, on the eastern edge of the suburb. Major thoroughfares are Crown Street, Cleveland Street, Bourke Street and Foveaux Street. Surry Hills is within easy walking distance of the Sydney CBD, and is included in a widening network of cycleways.

Major construction took place on the Surry Hills section of the CBD and South East Light Rail which opened in December 2019 and April 2020 respectively.[12] Transport for NSW managed this project.[13] It has been reported that there has been some disruption to local businesses because of the construction work taking place.[14]

Places of worship[edit]

- Chinese Presbyterian Church

- Christian Israelite Church

- Cityside Church (Australian Christian Churches)

- Dawn of Islam Mosque

- Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church

- King Faisal Mosque

- Self-Realization Fellowship Sydney Centre

- Society of Friends

- St Francis De Sales Catholic Church

- St Michael's Anglican Church[15]

- St Peters Catholic Church

- Surry Hills Baptist Church

- Sydney Streetlevel Mission (The Salvation Army)

- Vine Church[16]

Landmarks[edit]

- Sydney Police Centre [17]

- Centennial Plaza

- Belvoir Street Theatre

- Prince Alfred Park & Swimming Pool

- Tom Mann Theatre

- Harmony Park

- Ward Park, Devonshire Street

- Rainbow Crossing, Taylor Square

- Surry Hills Library and Community Centre, Crown Street

- The Kirk, Cleveland Street

Restaurants[edit]

Surry Hills boasts a diverse range of cafes and restaurants serving a wide variety of cooking styles and cultures.[18] The suburb has one of the highest, if not the highest, concentration of restaurants in Sydney.[19] Local chefs include Andrew Cibej and Bill Granger.

Pubs and bars[edit]

Because of its industrial and commercial history, the Surry Hills area contains a significant number of pubs. The style of pubs range from the Victorian period to Federation and Art Deco pubs from the mid-1900s. Many of these have been refurbished in recent years to include restaurants and modern facilities.

Heritage buildings[edit]

Surry Hills has a number of heritage-listed sites, including the following sites listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register:

- 197, 199, 201 Albion Street: 197, 199, 201 Albion Street terrace cottages[20]

- 203–205 Albion Street: 203–205 Albion Street cottages[21]

- 207 Albion Street: Durham Hall[22]

- 626–630 Bourke Street: Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church, Surry Hills[23]

- Centennial Park to College Street: Busby's Bore[24]

- Chalmers Street: Railway Institute Building[25]

- 146–164 Chalmers Street: Cleveland House, Surry Hills[26]

- 356 Crown Street: Crown Street Public School[27]

- 285 Crown Street: Crown Street Reservoir[28]

- 397 Crown Street: 1849 Stonemasonry workshop

- 416 Bourke Street: Hopetoun Hotel[29]

The following buildings are listed on the now defunct Register of the National Estate:[30]

- Bourke Street Public School, established in 1880 and located in heritage-listed buildings[31]

- Children's Court, Albion Street[32]

- Former Police Station, 703 Bourke Street (designed by Walter Liberty Vernon)

- Former Wesleyan Chapel, 348A Bourke Street

- Riley Street Infants School, 378–386 Riley Street

- Society of Friends Meeting House, Devonshire Street[33]

- St David's Hall, Arthur Street[34]

- St Michael's Anglican Church, hall and rectory, Albion Street

Housing[edit]

Surry Hills is largely composed of grand Victorian terraced houses and some complexes of public housing units to the west of Riley Street. Examples of converted buildings previously used as hospitals include Crown Street Hospital and St. Margaret's, in addition to other building conversions.

Schools[edit]

Bourke Street Public School, Crown Street Public School, Sydney Community College, Sydney Boys High School and Sydney Girls High School are notable examples. The Australian Institute of Music's Sydney Campus is also located in Surry Hills.

Population[edit]

Demographically, Surry Hills is now characterised as a mixture of wealthy newcomers who have gentrified the suburb, and long-time residents.

At the 2021 census, the population of Surry Hills was 15,828.[35] At the 2016 census, it had a population of 16,412.[36]

In 2021, 68.5% of dwellings were flats, units or apartments, compared to the Australian average of 14.2%. 29.1% are semi-detached terraced houses or townhouses, compared to the Australian average of 12.6%. Only 1.1% of dwellings are separate houses, compared to the Australian average of 72.3%. Surry Hills was categorised as a high wealth area, with a median weekly household income of $2,308, compared to the Australian average of $1,746.[35] Historically, the suburb had an influx of post-war immigrants from Europe, particularly those from Greece, Portugal[37] and Italy.

In 2021, 48.7% of people were born in Australia. The most common foreign countries of birth were England 6.4%, New Zealand 3.4%, China (excludes SARs and Taiwan) 3.3%, Thailand 3.0% and the United States of America 2.1%. 73.0% of people only spoke English at home. Other languages spoken at home included Cantonese 4.0%, Mandarin 3.0%, Thai 3.0%, Greek 2.0% and French 2.0%. [38]

47.5% of dwellings have no cars, compared to the Australian average of 7.3%. 11.0% of the population walked to work, compared to the Australian average of 2.5%, and 9.1% travelled to work by public transport, compared to the Australian average of 4.6%. 57.0% worked at home, compared to the Australian average of 21.0%. [35]

In 2021 Surry Hills was a significantly more irreligious suburb than the Australian average. Most (55.3%) reported no religion whilst 8.4% did not answer the question. The most common religions reported were Catholic 14.0%, Buddhism 4.8% and Anglican 4.8%.[35]

Notable people[edit]

- Tilly Devine (1900–1970), a prominent English-born crime syndicate figure and madam

- Jimmy Hannan (1937–2019), radio and television host

- Kate Leigh (1881–1964), (resided) a figure in the notorious Sydney razor gang wars

- Hugh Donald "Huge Deal" McIntosh (1876–1942), theatrical entrepreneur, sporting promoter and newspaper proprietor

- Jessica Mauboy, (born 1989) singer and actress

- Ruth Park (1917–2010), author, resided for a time in Surry Hills, where her first book, The Harp in the South (1948), was set

- Kenneth Slessor OBE (1901–1972), poet and author, many of whose poems were set in Surry Hills, Darlinghurst and Kings Cross

- Catherine Sutherland, (born 1974) actress

- Brett Whiteley AO (1939–1992), artist who resided and had a studio in Surry Hills, now the Brett Whiteley Studio

- Mike Whitney (born 1959), cricketer and television host

Gallery[edit]

-

Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church

-

Chinese Presbyterian Church

-

Crown Street Women's Hospital

-

Christian Israelite Church, Campbell Street

-

The Kirk, a deconsecrated Methodist church

-

Public School, Crown Street

-

Public School, Bourke Street

-

St Michael's Anglican Church

-

Heritage-listed St David's Hall, Arthur Street

References[edit]

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Surry Hills (suburb and locality)". Australian Census 2021 QuickStats. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ Gregory's Sydney Street Directory, Gregory's Publishing Company, 2002, Map 19

- ^ Butler, Katelin; Bruhn, Cameron (2017). The Apartment House. Thames & Hudson. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-500-50104-7.

- ^ The Book of Sydney Suburbs, Frances Pollon, Angus & Robertson, 1990, p. 249 ISBN 0-207-14495-8

- ^ Book of Sydney Suburbs, p. 249

- ^ Jackson, Sally. "Patineur Grotesque". Australian Screen Online. National Film and Sound Archive of Australia. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ Christopher Keating. "Surry Hills, The City's Backyard". Halstead Press, Australia. 1991 (ISBN 9781920831493)

- ^ David R. Keenan. CITY LINES of the Sydney Tramway System. Transit Press Australia,1991. (ISBN 0646064452)

- ^ "Surry Hills Markets website". shnc.org. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Surry Hills Festival 2014 website". surryhillsfestival.com. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Surry Hills Library and community centre upgrade". City of Sydney. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ About Sydney Light Rail

- ^ Sydney light rail opening delayed another two months to May 2020, Sydney Morning Herald, 4 October 2018

- ^ Surry Hills businesses count the toll of light rail construction, Daily Telegraph, 2 February 2017

- ^ "Untitled Document". www.surryhills.anglican.asn.au. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Vine Church – Surry Hills, Sydney". Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Sydney Police Centre location map". nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Surry Hills Takeaway and Surry Hills Food Delivery, Sydney - Menulog". www.menulog.com.au. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Sydney Morning Herald Good Food Guide

- ^ "Terrace Cottages". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00064. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Cottage". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00443. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Durham Hall". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00221. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H01816. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Busby's Bore". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00568. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Railway Institute Building". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H01257. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Cleveland House". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00065. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Crown Street Public School". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00562. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Crown Street Reservoir & Site". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H01323. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Hopetoun Hotel including Interior". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ The Heritage of Australia, Macmillan Company, 1981, p.2/88

- ^ "Bourke Street Public School - Home". www.bourkest-p.schools.nsw.edu.au. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Former Children's Court Building, Including Interior". New South Wales Heritage Database. Office of Environment & Heritage. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Society of Friends (Quaker) Meeting House Including Fence and Interior". New South Wales Heritage Database. Office of Environment & Heritage. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Former St David's Church Group Church and Residence Including Interiors". New South Wales Heritage Database. Office of Environment & Heritage. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Surry Hills". 2021 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Surry Hills". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ Keating, Chris (21 June 2009). "Surry Hills". p. 114. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "Report for Surry Hills". Microburbs. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

External links[edit]

- Wotherspoon, Garry; Keating, Chris (2009). "Surry Hills". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 28 September 2015. [CC-By-SA]

- Whitaker, Anne-Maree (2008). "Prince Alfred Park Surry Hills". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 28 September 2015. [CC-By-SA]

- demographics Archived 23 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading[edit]

- Keating, Christopher (1991). SURRY HILLS - The City's Backyard. Australia: Halstead Press. ISBN 9781920831493.