Paracelsus

Paracelsus | |

|---|---|

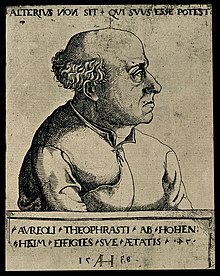

1538 portrait by Augustin Hirschvogel | |

| Born | Theophrastus von Hohenheim c. 1493[1] |

| Died | 24 September 1541 (aged 47) Salzburg, Archbishopric of Salzburg (present-day Austria) |

| Other names | Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus, Doctor Paracelsus |

| Education |

|

| Era | Renaissance philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Renaissance humanism |

Notable ideas | |

| Part of a series on |

| Esotericism |

|---|

|

Paracelsus (/ˌpærəˈsɛlsəs/; German: [paʁaˈtsɛlzʊs]; c. 1493[1] – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim[11][12]), was a Swiss[13] physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.[14][15]

He was a pioneer in several aspects of the "medical revolution" of the Renaissance, emphasizing the value of observation in combination with received wisdom. He is credited as the "father of toxicology".[16] Paracelsus also had a substantial influence as a prophet or diviner, his "Prognostications" being studied by Rosicrucians in the 17th century. Paracelsianism is the early modern medical movement inspired by the study of his works.[17]

Biography[edit]

Paracelsus was born in Egg an der Sihl,[18] a village close to the Etzel Pass in Einsiedeln, Schwyz. He was born in a house next to a bridge across the Sihl river. His father Wilhelm (d. 1534) was a chemist and physician, an illegitimate descendant of the Swabian noble Georg Bombast von Hohenheim (1453–1499), commander of the Order of Saint John in Rohrdorf.[19]

Paracelsus' mother was probably a native of the Einsiedeln region and a bondswoman of Einsiedeln Abbey, who before her marriage worked as superintendent in the abbey's hospital.[20] Paracelsus in his writings repeatedly made references to his rustic origins and occasionally used Eremita (from the name of Einsiedeln, meaning "hermitage") as part of his name.[21]

Paracelsus' mother probably died in 1502,[22] after which Paracelsus's father moved to Villach, Carinthia, where he worked as a physician, attending to the medical needs of the pilgrims and inhabitants of the cloister.[22] Paracelsus was educated by his father in botany, medicine, mineralogy, mining, and natural philosophy.[20] He received a profound humanistic and theological education from local clerics and the convent school of St. Paul's Abbey in the Lavanttal.[22] It is likely that Paracelsus received his early education mainly from his father.[23] Some biographers have claimed that he received tutoring from four bishops and Johannes Trithemius, abbot of Sponheim.[23] However, there is no record of Trithemius spending much time at Einsiedeln, nor of Paracelsus visiting Sponheim or Würzburg before Trithemius's death in 1516.[23] All things considered, Paracelsus almost certainly received instructions from their writings, and not from direct teaching in person.[23] At the age of 16, he started studying medicine at the University of Basel, later moving to Vienna. He gained his medical doctorate from the University of Ferrara in 1515 or 1516.[22][24]

Early career[edit]

"Paracelsus sought a universal knowledge"[27] that was not found in books or faculties. Thus, between 1517 and 1524, he embarked on a series of extensive travels around Europe. His wanderings led him from Italy to France, Spain, Portugal, England, Germany, Scandinavia, Poland, Russia, Hungary, Croatia, Rhodes, Constantinople, and possibly even Egypt.[27][28][29] During this period of travel, Paracelsus enlisted as an army surgeon and was involved in the wars waged by Venice, Holland, Denmark, and the Tatars. Then Paracelsus returned home from his travels in 1524.[27][28][29]

In 1524, "[a]fter visiting his father at Villach and finding no local opportunity to practice, he settled in Salzburg" as a physician,[30][28][29] and remained there until 1527.[28] "Since 1519/20 he had been working on his first medical writings, and he now completed Elf Traktat and Volumen medicinae Paramirum, which describe eleven common maladies and their treatment, and his early medical principles."[30] While he was returning to Villach and while he worked on his first medical writings, "he contemplated many fundamental issues such as the meaning of life and death, health, the causes of disease (internal imbalances or external forces), the place of humans in the world and in the universe, and the relationship between humans (including himself) and God."[28][29]

Basel (1526–1528)[edit]

In 1526, he bought the rights of citizenship in Strasbourg to establish his own practice. But soon after, he was called to Basel to the sickbed of printer Johann Frobenius and reportedly cured him.[31] During that time, the Dutch Renaissance humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam, also at the University of Basel, witnessed the medical skills of Paracelsus, and the two scholars initiated a dialogue, exchanging letters on medical and theological subjects.[32]

In 1527, Paracelsus was a licensed physician in Basel with the privilege of lecturing at the University of Basel. At that time, Basel was a centre of Renaissance humanism, and Paracelsus here came into contact with Erasmus of Rotterdam, Wolfgang Lachner, and Johannes Oekolampad. When Erasmus fell ill while staying in Basel, he wrote to Paracelsus: "I cannot offer thee a reward equal to thy art and knowledge—I surely offer thee a grateful soul. Thou hast recalled from the shades Frobenius who is my other half: if thou restorest me also thou restorest each through the other."[33]

Paracelsus' lectures at Basel university unusually were given in German, not Latin.[34] He stated that he wanted his lectures to be available to everyone. He published harsh criticism of the Basel physicians and apothecaries, creating political turmoil to the point of his life being threatened. In a display of his contempt for conventional medicine, Paracelsus publicly burned editions of the works of Galen and Avicenna. On 23 June 1527, he burnt a copy of Avicenna's Canon of Medicine, an enormous tome that was a pillar of academic study, in market square.[35] He was prone to many outbursts of abusive language, abhorred untested theory, and ridiculed anybody who placed more importance on titles than practice: 'if disease put us to the test, all our splendour, title, ring, and name will be as much help as a horse's tail'.[31] During his time as a professor at the University of Basel, he invited barber-surgeons, alchemists, apothecaries, and others lacking academic background to serve as examples of his belief that only those who practised an art knew it: "The patients are your textbook, the sickbed is your study."[31] Paracelsus was compared with Martin Luther because of his openly defiant acts against the existing authorities in medicine.[36] But Paracelsus rejected that comparison,[37] famously stating: "I leave it to Luther to defend what he says and I will be responsible for what I say. That which you wish to Luther, you wish also to me: You wish us both in the fire."[38] A companion during the Basel years expressed a quite unflattering opinion on Paracelsus: "The two years I passed in his company he spent in drinking and gluttony, day and night. He could not be found sober an hour or two together, in particular after his departure from Basel."[39] threatened with an unwinnable lawsuit,[clarification needed] he left Basel for Alsace in February 1528.

Later career[edit]

In Alsace, Paracelsus took up the life of an itinerant physician once again. After staying in Colmar with Lorenz Fries, and briefly in Esslingen, he moved to Nuremberg in 1529. His reputation went before him, and the medical professionals excluded him from practising.

The name Paracelsus is first attested in this year, used as a pseudonym for the publication of a Practica of political-astrological character in Nuremberg.[40] Pagel (1982) supposes that the name was intended for use as the author of non-medical works, while his real name Theophrastus von Hohenheim was used for medical publications. The first use of Doctor Paracelsus in a medical publication was in 1536, as the author of the Grosse Wundartznei. The name is usually interpreted as either a Latinization of Hohenheim (based on celsus "high, tall") or as the claim of "surpassing Celsus". It has been argued that the name was not the invention of Paracelsus himself, who would have been opposed to the humanistic fashion of Latinized names, but was given to him by his circle of friends in Colmar in 1528. It is difficult to interpret but does appear to express the "paradoxical" character of the man, the prefix "para" suggestively being echoed in the titles of Paracelsus's main philosophical works, Paragranum and Paramirum (as it were, "beyond the grain" and "beyond wonder"), a paramiric treatise having been announced by Paracelsus as early as 1520.[41]

The great medical problem of this period was syphilis, possibly recently imported from the West Indies and running rampant as a pandemic completely untreated. Paracelsus vigorously attacked the treatment with guaiac wood as useless, a scam perpetrated by the Fugger of Augsburg as the main importers of the wood in two publications on the topic. When his further stay in Nuremberg had become impossible, he retired to Beratzhausen, hoping to return to Nuremberg and publish an extended treatise on the "French sickness"; but its publication was prohibited by a decree of the Leipzig faculty of medicine, represented by Heinrich Stromer, a close friend and associate of the Fugger family.[42]

In Beratzhausen, Paracelsus prepared Paragranum, his main work on medical philosophy, completed 1530. Moving on to St. Gall, he then completed his Opus Paramirum in 1531, which he dedicated to Joachim Vadian. From St. Gall, he moved on to the land of Appenzell, where he was active as lay preacher and healer among the peasantry. In the same year, he visited the mines in Schwaz and Hall in Tyrol, working on his book on miners' diseases. He moved on to Innsbruck, where he was once again barred from practising. He passed Sterzing in 1534, moving on to Meran, Veltlin, and St. Moritz, which he praised for its healing springs. In Meran, he came in contact with the socioreligious programs of the Anabaptists. He visited Pfäfers Abbey, dedicating a separate pamphlet to its baths (1535). He passed Kempten, Memmingen, Ulm, and Augsburg in 1536. He finally managed to publish his Die grosse Wundartznei ("The Great Surgery Book"), printed in Ulm, Augsburg, and Frankfurt in this year.[43]

His Astronomia magna (also known as Philosophia sagax) was completed in 1537 but not published until 1571. It is a treatise on hermeticism, astrology, divination, theology, and demonology that laid the basis of Paracelsus's later fame as a "prophet". His motto Alterius non sit qui suus esse potest ("Let no man belong to another who can belong to himself") is inscribed on a 1538 portrait by Augustin Hirschvogel.

Death and legacy[edit]

In 1541, Paracelsus moved to Salzburg where he died on 24 September. He was buried in St. Sebastian's cemetery in Salzburg. His remains were relocated inside St. Sebastian's church in 1752.

After his death, the movement of Paracelsianism was seized upon by many wishing to subvert the traditional Galenic physics, and his therapies became more widely known and used. His manuscripts have been lost, but many of his works which remained unpublished during his lifetime were edited by Johannes Huser of Basel during 1589 to 1591. His works were frequently reprinted and widely read during the late 16th to early 17th centuries, and although his "occult" reputation remained controversial, his medical contributions were universally recognized: a 1618 pharmacopeia by the Royal College of Physicians in London included "Paracelsian" remedies.[44]

The late 16th century saw substantial production of Pseudo-Paracelsian writing, especially letters attributed to Paracelsus, to the point where biographers find it impossible to draw a clear line between genuine tradition and legend.[45]

Philosophy[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Hermeticism |

|---|

|

As a physician of the early 16th century, Paracelsus held a natural affinity with the Hermetic, Neoplatonic, and Pythagorean philosophies central to the Renaissance, a world-view exemplified by Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola.[citation needed] Astrology was a very important part of Paracelsus's medicine and he was a practising astrologer, as were many of the university-trained physicians working at that time in Europe. Paracelsus devoted several sections in his writings to the construction of astrological talismans for curing disease. [citation needed]

Paracelsus's approach to science was heavily influenced by his religious beliefs. He believed that science and religion were inseparable, and scientific discoveries were direct messages from God. Thus, he believed it was mankind's divine duty to uncover and understand all of His message.[46] Paracelsus also believed that the virtues that make up natural objects are not natural, but supernatural, and existed in God before the creation of the universe. Because of this, when the Earth and the Heavens eventually dissipate, the virtues of all natural objects will continue to exist and simply return to God.[46] His philosophy about the true nature of the virtues is reminiscent of Aristotle's idea of the natural place of elements. To Paracelsus, the purpose of science is not only to learn more about the world around us, but also to search for divine signs and potentially understand the nature of God.[46] If a person who doesn't believe in God became a physician, he would not have standing in God's eyes and would not succeed in their work because he did not practice in his name. Becoming an effective physician requires faith in God.[47] Paracelsus saw medicine as more than just a perfunctory practice. To him, medicine was a divine mission, and good character combined with devotion to God was more important than personal skill. He encouraged physicians to practice self-improvement and humility along with studying philosophy to gain new experiences.[48]

Chemistry and alchemy[edit]

Chemistry in medicine[edit]

Paracelsus was one of the first medical professors to recognize that physicians required a solid academic knowledge in the natural sciences, especially chemistry. Paracelsus pioneered the use of chemicals and minerals in medicine.

Zinc[edit]

He was probably the first to give the element zinc (zincum) its modern name,[49][50] in about 1526, likely based on the sharp pointed appearance of its crystals after smelting (zinke translating to "pointed" in German). Paracelsus invented chemical therapy, chemical urinalysis, and suggested a biochemical theory of digestion.[31] Paracelsus used chemistry and chemical analogies in his teachings to medical students and to the medical establishment, many of whom found them objectionable.[51]

Hydrogen[edit]

Paracelsus in the beginning of the sixteenth century had unknowingly observed hydrogen as he noted that in reaction when acids attack metals, gas was a by-product.[52] Later, Théodore de Mayerne repeated Paracelsus's experiment in 1650 and found that the gas was flammable. However, neither Paracelsus nor de Mayerne proposed that hydrogen could be a new element.[53]

Elements[edit]

Classical elements[edit]

Paracelsus largely rejected the philosophies of Aristotle and Galen, as well as the theory of humours. Although he did accept the concept of the four elements—water, air, fire, and earth; he saw them as a foundation for other properties on which to build.[54] In a posthumously published book entitled, A Book on Nymphs, Sylphs, Pygmies, and Salamanders, and on the Other Spirits, Paracelsus also described four elemental beings, each corresponding to one of the four elements: Salamanders, which correspond to fire; Gnomes, corresponding to earth; Undines, corresponding to water; and Sylphs, corresponding to air.[55][56]

Elements, heaven and Earth[edit]

Paracelsus often viewed fire as the Firmament that sat between air and water in the heavens. Paracelsus often uses an egg to help describe the elements. In his early model, he claimed that air surrounded the world like an egg shell. The egg white below the shell is like fire because it has a type of chaos to it that allows it to hold up earth and water. The earth and water make up a globe which, in his egg analogy, is the yolk. In De Meteoris, Paracelsus claims the firmament is the heavens.[57]

Tria prima[edit]

From his study of the elements, Paracelsus adopted the idea of tripartite alternatives to explain the nature of medicines, which he thought to be composed of the tria prima ('three primes' or principles): a combustible element (sulphur), a fluid and changeable element (mercury), and a solid, permanent element (salt). The first mention of the mercury-sulphur-salt model was in the Opus paramirum dating to about 1530.[58] Paracelsus believed that the principles sulphur, mercury, and salt contained the poisons contributing to all diseases.[54] He saw each disease as having three separate cures depending on how it was afflicted, either being caused by the poisoning of sulphur, mercury, or salt. Paracelsus drew the importance of sulphur, salt, and mercury from medieval alchemy, where they all occupied a prominent place. He demonstrated his theory by burning a piece of wood. The fire was the work of sulphur, the smoke was mercury, and the residual ash was salt.[58] Paracelsus also believed that mercury, sulphur, and salt provided a good explanation for the nature of medicine because each of these properties existed in many physical forms. The tria prima also defined the human identity. Salt represented the body; mercury represented the spirit (imagination, moral judgment, and the higher mental faculties); sulphur represented the soul (the emotions and desires). By understanding the chemical nature of the tria prima, a physician could discover the means of curing disease. With every disease, the symptoms depended on which of the three principals caused the ailment.[58] Paracelsus theorized that materials which are poisonous in large doses may be curative in small doses; he demonstrated this with the examples of magnetism and static electricity, wherein a small magnet can attract much larger pieces of metal.[58]

Tria prima in The Sceptical Chymist[edit]

Even though Paracelsus accepted the four classical elements, in Robert Boyle's The Sceptical Chymist, published in 1661 in the form of a dialogue between friends, Themistius, the Aristotelian of the party, speaks of the three principles as though they were meant to replace, rather than complement, the classical elements and compares Paracelsus' theory of the elements unfavourably with that of Aristotle:

This Doctrine is very different from the whimseys of Chymists ... whose Hypotheses ... often fram’d in one week, are perhaps thought fit to be laughed at the next; and being built perchance but upon two or three Experiments are destroyed by a third or fourth, whereas the doctrine of the four Elements was fram’d by Aristotle after he had ... considered those Theories of former Philosophers, which are now with great applause revived... And had so judiciously detected ... the ... defects of former Hypotheses concerning the Elements, that his Doctrine ... has been ever since deservedly embraced by the letter’d part of Mankind: All the Philosophers that preceded him having in their several ages contributed to the compleatness of this Doctrine... Nor has an Hypothesis so ... maturely established been called in Question till in the last Century Paracelsus and some ... Empiricks, rather then ... Philosophers ... began to rail at the Peripatetick Doctrine ... and to tell the credulous World, that they could see but three Ingredients in mixt Bodies ... instead of Earth, and Fire, and Vapour, Salt, Sulphur, and Mercury; to which they gave the canting title of Hypostatical Principles: but when they came to describe them ...’tis almost ... impossible for any sober Man to find their meaning.[59]

Boyle—speaking through other characters—rejected both Paracelsus’ three principles (sulfur, mercury, and salt), and the “Aristotelian” elements (earth, water, air, and fire), or any system with a pre-determined number of elements. In fact, Boyle’s arguments were mainly directed against Paracelsus’ theory as being the one more in line with experience, so that arguments against it should be at least as valid against the Aristotelian view.

Much of what I am to deliver ... may be indifferently apply’d to the four Peripatetick Elements, and the three Chymical Principles ... the Chymical Hypothesis seeming to be much more countenanc’d by Experience then the other, it will be expedient to insist chiefly upon the disproving of that; especially since most of the Arguments that are imploy’d against it, may, by a little variation, be made ... at least as strongly against the less plausible, Aristotelian Doctrine.[60]

Contributions to medicine[edit]

Hermeticism[edit]

His hermetic beliefs were that sickness and health in the body relied upon the harmony of humans (microcosm) and nature (macrocosm). He took a different approach from those before him, using this analogy not in the manner of soul-purification but in the manner that humans must have certain balances of minerals in their bodies, and that certain illnesses of the body had chemical remedies that could cure them. As a result of this hermetical idea of harmony, the universe's macrocosm was represented in every person as a microcosm. An example of this correspondence is the doctrine of signatures used to identify curative powers of plants. If a plant looked like a part of the body, then this signified its ability to cure this given anatomy. Therefore, the root of the orchid looks like a testicle and can therefore heal any testicle-associated illness.[62] Paracelsus mobilized the microcosm-macrocosm theory to demonstrate the analogy between the aspirations to salvation and health. As humans must ward off the influence of evil spirits with morality, they must also ward off diseases with good health.[58]

Paracelsus believed that true anatomy could only be understood once the nourishment for each part of the body was discovered. He believed that one must therefore know the influence of the stars on these particular body parts.[63] Diseases were caused by poisons brought from the stars. However, 'poisons' were not necessarily something negative, in part because related substances interacted, but also because only the dose determined if a substance was poisonous. Paracelsus claimed in contrast to Galen, that like cures like. If a star or poison caused a disease, then it must be countered by another star or poison.[63] Because everything in the universe was interrelated, beneficial medical substances could be found in herbs, minerals, and various chemical combinations thereof. Paracelsus viewed the universe as one coherent organism that is pervaded by a uniting, life-giving spirit, and this in its entirety, humans included, was 'God'. His beliefs put him at odds with the Catholic Church, for which there necessarily had to be a difference between the creator and the created.[64] Therefore, some have considered him to be a Protestant.[65][66][67][68]

Discoveries and treatments[edit]

Paracelsus is frequently credited with reintroducing opium to Western Europe during the German Renaissance. He extolled the benefits of opium, and of a pill he called laudanum, which has frequently been asserted by others to have been an opium tincture. Paracelsus did not leave a complete recipe, and the known ingredients differ considerably from 17th-century laudanum.[69]

Paracelsus invented, or at least named a sort of liniment, opodeldoc, a mixture of soap in alcohol, to which camphor and sometimes a number of herbal essences, most notably wormwood, were added. Paracelsus's recipe forms the basis for most later versions of liniment.[70]

His work Die große Wundarzney is a forerunner of antisepsis. This specific empirical knowledge originated from his personal experiences as an army physician in the Venetian wars. Paracelsus demanded that the application of cow dung, feathers and other noxious concoctions to wounds be surrendered in favour of keeping the wounds clean, stating, "If you prevent infection, Nature will heal the wound all by herself."[31] During his time as a military surgeon, Paracelsus was exposed to the crudity of medical knowledge at the time, when doctors believed that infection was a natural part of the healing process. He advocated for cleanliness and protection of wounds, as well as the regulation of diet. Popular ideas of the time opposed these theories and suggested sewing or plastering wounds.[71] Historians of syphilitic disease credit Paracelsus with the recognition of the inherited[clarification needed] character of syphilis. In his first medical publication, a short pamphlet on syphilis treatment that was also the most comprehensive clinical description the period ever produced, he wrote a clinical description of syphilis in which he maintained that it could be treated by carefully measured doses of mercury.[71] Similarly, he was the first to discover that the disease could only be contracted by contact.[31]

Hippocrates put forward the theory that illness was caused by an imbalance of the four humours: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. These ideas were further developed by Galen into an extremely influential and highly persistent set of medical beliefs that were to last until the mid-1850s. Contrarily, Paracelsus believed in three humours: salt (representing stability), sulphur (representing combustibility), and mercury (representing liquidity); he defined disease as a separation of one humour from the other two. He believed that body organs functioned alchemically, that is, they separated pure from impure.[51] The dominant medical treatments in Paracelsus's time were specific diets to help in the "cleansing of the putrefied juices" combined with purging and bloodletting to restore the balance of the four humours. Paracelsus supplemented and challenged this view with his beliefs that illness was the result of the body being attacked by outside agents. He objected to excessive bloodletting, saying that the process disturbed the harmony of the system, and that blood could not be purified by lessening its quantity.[71] Paracelsus believed that fasting helped enable the body to heal itself. 'Fasting is the greatest remedy, the physician within.' [72]

Paracelsus gave birth to clinical diagnosis and the administration of highly specific medicines. This was uncommon for a period heavily exposed to cure-all remedies. The germ theory was anticipated by him as he proposed that diseases were entities in themselves, rather than states of being. Paracelsus prescribed black hellebore to alleviate certain forms of arteriosclerosis. Lastly, he recommended the use of iron for "poor blood" and is credited with the creation of the terms "chemistry," "gas," and "alcohol".[31]

During Paracelsus's lifetime and after his death, he was often celebrated as a wonder healer and investigator of those folk medicines that were rejected by the fathers of medicine (e.g. Galen, Avicenna). It was believed that he had success with his own remedies curing the plague, according to those that revered him. Since effective medicines for serious infectious diseases weren't invented before the 19th century, Paracelsus came up with many prescriptions and concoctions on his own. For infectious diseases with fever, it was common to prescribe diaphoretics and tonics that at least gave temporary relief. Also many of his remedies contained the famed "theriac", a preparation derived from oriental medicine sometimes containing opium. The following prescription by Paracelsus was dedicated to the village of Sterzing:

Also sol das trank gemacht werden, dadurch die pestilenz im schweiss ausgetrieben wird: (So the potion should be made, whereby the pestilence is expelled in sweat:)

eines guten gebranten weins...ein moß, (Medicinal brandy)

eines guten tiriaks zwölf lot, (Theriac)

myrrhen vier lot, (Myrrh)

wurzen von roßhuf sechs lot, (Tussilago sp.)

sperma ceti,

terrae sigillatae ietlichs ein lot, (Medicinal earth)

schwalbenwurz zwei lot, (Vincetoxicum sp.)

diptan, bibernel, baldrianwurzel ietlichs ein lot (Dictamnus albus, Valerian, Pimpinella)

gaffer ein quint. (Camphor)

Dise ding alle durch einander gemischet, in eine sauberes glas wol gemacht, auf acht tag in der sonne stehen lassen, nachfolgents dem kranken ein halben löffel eingeben... (Mix all these things together, put them into a clean glass, let them stand in the sun for eight days, then give the sick person half a spoonful...)— E. Kaiser, "Paracelsus. 10. Auflage. Rowohlt's Monographien. p. 115", Reinbek bei Hamburg. 1090-ISBN 3-499-50149-X (1993)

One of his most overlooked achievements was the systematic study of minerals and the curative powers of alpine mineral springs. His countless wanderings also brought him deep into many areas of the Alps, where such therapies were already practised on a less common scale than today.[73] Paracelsus's major work On the Miners' Sickness and Other Diseases of Miners (German: Von der Bergaucht und anderen Bergkrankheiten) presented his observation of diseases of miners and the effects of various minerals and metals in the human organism.[74]

Toxicology[edit]

Paracelsus extended his interest in chemistry and biology to what is now considered toxicology. He clearly expounded the concept of dose response in his Third Defence, where he stated that "Solely the dose determines that a thing is not a poison." (Sola dosis facit venenum "Only the dose makes the poison")[75] This was used to defend his use of inorganic substances in medicine as outsiders frequently criticized Paracelsus's chemical agents as too toxic to be used as therapeutic agents.[51] His belief that diseases locate in a specific organ was extended to inclusion of target organ toxicity; that is, there is a specific site in the body where a chemical will exert its greatest effect. Paracelsus also encouraged using experimental animals to study both beneficial and toxic chemical effects.[51] Paracelsus was one of the first European scientists to introduce chemistry to medicine. He advocated the use of inorganic salts, minerals, and metals for medicinal purposes. He held the belief that organs in the body operated on the basis of separating pure substances from impure ones. Humans must eat to survive and they eat both pure and impure things. It is the function of organs to separate the impure from the pure. The pure substances will be absorbed by the body while the impure will exit the body as excrement.[76] He did not support Hippocrate's theory of the four humours. Instead of four humours, Paracelsus believed there were three: salt, sulphur, and mercury which represent stability, combustibility, and liquidity respectively. Separation of any one of these humours from the other two would result in disease.[48] To cure a disease of a certain intensity, a substance of similar nature but the opposite intensity should be administered. These ideas constitute Paracelsus's principles of similitude and contrariety, respectively.[48]

Psychosomatism[edit]

In his work Von den Krankeiten Paracelsus writes: "Thus, the cause of the disease chorea lasciva [Sydenham's chorea, or St. Vitus' Dance] is a mere opinion and idea, assumed by imagination, affecting those who believe in such a thing. This opinion and idea are the origin of the disease both in children and adults. In children the case is also imagination, based not on thinking but on perceiving, because they have heard or seen something. The reason is this: their sight and hearing are so strong that unconsciously they have fantasies about what they have seen or heard."[77] Paracelsus called for the humane treatment of the mentally ill as he saw them not to be possessed by evil spirits, but merely 'brothers' ensnared in a treatable malady."[31] Paracelsus is one of the first physicians to suggest that mental well-being and a moral conscience had a direct effect on physical health. He proposed that the state of a person's psyche could cure and cause disease. Theoretically, a person could maintain good health through sheer will.[48] He also stated that whether or not a person could succeed in their craft depended on their character. For example, if a physician had shrewd and immoral intentions then they would eventually fail in their career because evil could not lead to success.[47] When it came to mental illness, Paracelsus stressed the importance of sleep and sedation as he believed sedation (with sulphur preparations) could catalyse healing and cure mental illness.[76]

Reception and legacy[edit]

Portraits[edit]

The oldest surviving portrait of Paracelsus is a woodcut by Augustin Hirschvogel, published in 1538, still during Paracelsus's lifetime. A still older painting by Quentin Matsys has been lost, but at least three 17th-century copies survive, one by an anonymous Flemish artist, kept in the Louvre, one by Peter Paul Rubens, kept in Brussels, and one by a student of Rubens, now kept in Uppsala. Another portrait by Hirschvogel, dated 1540, claims to show Paracelsus "at the age of 47" (sue aetatis 47), i.e. less than a year before his death. In this portrait, Paracelsus is shown as holding his sword, gripping the spherical pommel with the right hand. Above and below the image are the mottos Alterius non sit qui suus esse potest ("Let no man belong to another who can belong to himself") and Omne donum perfectum a Deo, inperfectum a Diabolo ("All perfect gifts are from God, [all] imperfect [ones] from the Devil"); later portraits give a German rendition in two rhyming couplets (Eines andern Knecht soll Niemand sein / der für sich bleiben kann allein /all gute Gaben sint von Got / des Teufels aber sein Spot).[78] Posthumous portraits of Paracelsus, made for publications of his books during the second half of the 16th century, often show him in the same pose, holding his sword by its pommel.

The so-called "Rosicrucian portrait", published with Philosophiae magnae Paracelsi (Heirs of Arnold Birckmann, Cologne, 1567), is closely based on the 1540 portrait by Hirschvogel (but mirrored, so that now Paracelsus's left hand rests on the sword pommel), adding a variety of additional elements: the pommel of the sword is inscribed by Azoth, and next to the figure of Paracelsus, the Bombast von Hohenheim arms are shown (with an additional border of eight crosses patty).[79] Shown in the background are "early Rosicrucian symbols", including the head of a child protruding from the ground (indicating rebirth). The portrait is possibly a work by Frans Hogenberg, acting under the directions of Theodor Birckmann (1531/33–1586).

Paracelsianism and Rosicrucianism[edit]

Paracelsus was especially venerated by German Rosicrucians, who regarded him as a prophet, and developed a field of systematic study of his writings, which is sometimes called "Paracelsianism", or more rarely "Paracelsism". Francis Bacon warned against Paracelsus and the Rosicrucians, judging that "the ancient opinion that man was microcosmus" had been "fantastically strained by Paracelsus and the alchemists".[80]

"Paracelsism" also produced the first complete edition of Paracelsus's works. Johannes Huser of Basel (c. 1545–1604) gathered autographs and manuscript copies, and prepared an edition in ten volumes during 1589–1591.[81]

The prophecies contained in Paracelsus's works on astrology and divination began to be separately edited as Prognosticon Theophrasti Paracelsi in the early 17th century. His prediction of a "great calamity just beginning" indicating the End Times was later associated with the Thirty Years' War, and the identification of Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden as the "Lion from the North" is based in one of Paracelsus's "prognostications" referencing Jeremiah 5:6.[82]

Carl Gustav Jung studied Paracelsus. He wrote two essays on Paracelsus, one delivered in the house in which Paracelsus was born at Einsiedeln in June 1929, the other to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Paracelsus's death in 1941 at Zurich.[83]

In popular culture[edit]

A number of fictionalized depictions of Paracelsus have been published in modern literature. The first presentation of Paracelsus's life in the form of a historical novel was published in 1830 by Dioclès Fabre d'Olivet (1811–1848, son of Antoine Fabre d'Olivet),[84] Robert Browning wrote a long poem based on the life of Paracelsus, entitled Paracelsus, published 1835.[85] Meinrad Lienert in 1915 published a tale (which he attributed to Gall Morel) about Paracelsus's sword.[86]

Paracelsus has been cited as one of the inspirations for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

The Fullmetal Alchemist character Van Hohenheim is named after Paracelsus, and in the alternate anime continuity is him.

Arthur Schnitzler wrote a verse play Paracelsus in 1899. Erwin Guido Kolbenheyer wrote a novel trilogy (Paracelsus-Trilogie), published during 1917–26. Martha Sills-Fuchs (1896–1987) wrote three völkisch plays with Paracelsus as the main character during 1936–1939 in which Paracelsus is depicted as the prophetic healer of the German people.[87] The German drama film Paracelsus was made in 1943, directed by Georg Wilhelm Pabst.[88] Also in 1943, Richard Billinger wrote a play Paracelsus for the Salzburg Festival.[89]

Mika Waltari's Mikael Karvajalka (1948) has a scene fictionalizing Paracelsus's acquisition of his legendary sword. Paracelsus is the main character of Jorge Luis Borges's short story "La rosa de Paracelso" (anthologized in Shakespeare's Memory, 1983). The Rose of Paracelsus: On Secrets and Sacraments, borrowing from Jorge Luis Borges, is also a novel by William Leonard Pickard.[90]

Paracelsus von Hohenheim is a caster class servant, and serves as both a minor antagonist and playable character in Fate/Grand Order.

A fictionalization of Paracelsus is a featured character in the novel The Enterprise of Death (2011) by Jesse Bullington.

A.B.A, a Homunculus from the Guilty Gear series, wields a living, key-shaped ax which she named "Paracelsus".

In the games Darkest Dungeon and Darkest Dungeon II, the predetermined name for the playable plague doctor character is "Paracelsus".

A fictionalization of “Paracelsus” is featured as the main antagonist of the show Warehouse 13 in its fifth season. (2013)

In the video game "Lies of P", a character is revealed to actually be Paracelsus in the post-game cutscene.

In the world of Harry Potter, Paracelsus is a wizard and is credited with the discovery of parseltongue, the ability to speak with snakes.

Works[edit]

![]() German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Paracelsus

German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Paracelsus

Because of the work of Karl Widemann, who copied over 30 years the work of Paracelsus, many unpublished works survived.

- Published during his lifetime

- De gradibus et compositionibus receptorum naturalium, 1526.

- Vom Holtz Guaico (on guaiacum), 1529.

- Practica, gemacht auff Europen 1529.

- Von der Frantzösischen kranckheit Drey Bücher (on syphilis), 1530.

- Von den wunderbarlichen zeychen, so in vier jaren einander nach im Hymmelgewelcke und Luft ersehen 1534

- Von der Bergsucht oder Bergkranckheiten (on miners' diseases), 1534.

- Vonn dem Bad Pfeffers in Oberschwytz gelegen (Pfäfers baths), 1535.

- Praktica Teutsch auff das 1535 Jar 1535

- Die große Wundarzney ("Great Book of Surgery"), Ulm 1536 (Hans Varnier); Augsburg 1536 (Haynrich Stayner (=Steyner)), Frankfurt 1536 (Georg Raben/ Weygand Hanen).

- Prognosticatio Ad Vigesimum Quartum annum duratura 1536

- Posthumous publications

- Wundt unnd Leibartznei. Frankfurt: Christian Egenolff, 1549 (reprinted 1555, 1561).

- Das Buch Paramirum, Mulhouse: Peter Schmid, 1562.

- Aureoli Theophrasti Paracelsi schreiben Von Tartarjschen kranckheiten, nach dem alten nammen, Vom grieß sand vnnd [unnd] stein, Basel, c. 1563.

- Das Buch Paragranvm Avreoli Theophrasti Paracelsi: Darinnen die vier Columnae, als da ist, Philosophia, Astronomia, Alchimia, vnnd Virtus, auff welche Theophrasti Medicin fundirt ist, tractirt werden, Frankfurt, 1565.

- Opvs Chyrvrgicvm, Frankfurt, 1565.

- Ex Libro de Nymphis, Sylvanis, Pygmaeis, Salamandris, et Gigantibus etc. Nissae Silesiorum, Excudebat Ioannes Cruciger (1566)

- Von den Krankheiten so die Vernunfft Berauben. Basel, 1567.

- Philosophia magna, tractus aliquot, Cöln, 1567.

- Philosophiae et Medicinae utriusque compendium, Basel, 1568.

- Neun Bücher Archidoxis. Translated into Latin by Adam Schröter. Kraków: Maciej Wirzbięta, 1569.

- Zwölff Bücher, darin alle gehaimnüß der natur eröffnet, 1570

- Astronomia magna: oder Die gantze Philosophia sagax der grossen und kleinen Welt , Frankfurt, 1571.

- De natura rerum libri septem: Opuscula verè aurea; Ex Germanica lingua in Latinam translata per M. Georgium Forbergium Mysium philosophiae ac medicinae studiosum, 1573.

- De Peste, Strasbourg: Michael Toxites, Bey Niclauss Wyriot, 1574.

- Volumen Paramirum, Strasbourg: Christian Mülller, 1575.

- Metamorphosis Theophrasti Paracelsi: Dessen werck seinen meister loben wirt, Basel, 1574.

- Von der Wundartzney: Ph. Theophrasti von Hohenheim, beyder Artzney Doctoris, 4 Bücher. Basel: Peter Perna, 1577.

- Kleine Wundartzney. Basel: Peter Perna, 1579.

- Opus Chirurgicum, Bodenstein, Basel, 1581.

- Huser quart edition (medicinal and philosophical treatises), ten volmes, Basel, 1589–1591; Huser's edition of Paracelsus' surgical works was published posthumously in Strasbourg, 1605.

- vol. 1, In diesem Theil werden begriffen die Bücher, welche von Ursprung und herkommen, aller Kranckheiten handeln in Genere. Basel. 1589 [VD16 P 365] urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00022502-1

- vol. 2, Dieser Theil begreifft fürnemlich die Schrifften, inn denen die Fundamenta angezeigt werde[n], auff welchen die Kunst der rechten Artzney stehe, und auß was Büchern dieselbe gelehrnet werde, Basel. 1589 [VD16 P 367] urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00022503-6

- vol. 3, Inn diesem Theil werden begriffen deren Bücher ettliche, welche von Ursprung, Ursach und Heylung der Kranckheiten handeln in Specie. Basel, 1589 [VD16 P 369] urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00022504-2

- vol. 4, In diesem Theil werden gleichfals, wie im Dritten, solche Bücher begriffen, welche von Ursprung, Ursach unnd Heilung der Kranckheiten in Specie handlen. Basel, 1589 [VD16 P 371] urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00022505-7

- vol. 5, Bücher de Medicina Physica Basel, 1589 urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10164682-7

- vol. 6, In diesem Tomo seind begriffen solche Bücher, in welchen deß mehrer theils von Spagyrischer Bereitung Natürlicher dingen, die Artzney betreffend, gehandelt wirt. Item, ettliche Alchimistische Büchlin, so allein von der Transmutation der Metallen tractiren. Basel, 1590 [VD16 P 375] urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00022506-2

- vol. 7, In diesem Theil sind verfasset die Bücher, in welchen fürnemlich die Kräfft, Tugenden und Eigenschafften Natürlicher dingen, auch derselben Bereitdungen, betreffent die Artzney, beschriben, werden. Basel, 1590 [VD16 P 376] urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00022507-8

- vol. 8, In diesem Tomo (welcher der Erste unter den Philosophischen) werden solche Bücher begriffen, darinnen fürnemlich die Philosophia de Generationibus & Fructibus quatuor Elementorum beschrieben wirdt. Basel, 1590 [VD16 P 377] urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00022508-3

- vol. 9, Diser Tomus (welcher der Ander unter den Philosophischen) begreifft solcher Bücher, darinnen allerley Natürlicher und Ubernatürlicher Heymligkeiten Ursprung, Ursach, Wesen und Eigenschafft, gründtlich und warhafftig beschriben werden. Basel, 1591 [VD16 P 380] urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00022509-3

- vol. 10, Dieser Theil (welcher der Dritte unter den Philosophischen Schrifften) begreifft fürnemlich das treffliche Werck Theophrasti, Philosophia Sagax, oder Astronomia Magna genannt: Sampt ettlichen andern Opusculis, und einem Appendice. Basel, 1591 [VD16 P 381] urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00022510-5, Frankfurt 1603

- Klage Theophrasti Paracelsi, uber seine eigene Discipel, unnd leichtfertige Ertzte, Darbeneben auch unterricht, wie er wil, daß ein rechter Artzt soll geschickt seyn, und seine Chur verrichten, und die Patienten versorgen, etc.; Auß seinen Büchern auff das kürtzste zusammen gezogen, Wider die Thumkünen selbwachsende, Rhumrhätige, apostatische Ertzte, und leichtfertige Alchymistische Landtstreicher, die sich Paracelsisten nennen; … jetzo zum ersten also zusammen bracht, und in Truck geben. 1594 [VD16 P 383] urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00015650-2

- Kleine Wund-Artzney. Straßburg (Ledertz), Benedictus Figulus. 1608.

- Opera omnia medico-chemico-chirurgica, Genevae, Vol. 3, 1658.

- Prognosticon Theophrasti Paracelsi, vol. 4 of VI Prognostica Von Verenderung vnd zufaelligem Glueck vnd Vnglueck der ... Potentaten im Roemischen Reich, Auch des Tuercken vnd Pabst ed. Henricus Neotechnus, 1620.

- Modern editions

- Paracelsus: Sämtliche Werke: nach der 10 Bändigen Huserschen Gesamtausgabe (1589–1591) zum erstenmal in neuzeitliches deutsch übersetzt, mit Einleitung, Biographie, Literaturangaben und erklärenden Anmerkungen. Edited by Bernhard Aschner. 4 volumes. Jena: G. Fisher, 1926–1932.

- Paracelsus: Sämtliche Werke. Edited by Karl Sudhoff, Wilhelm Matthiessen, and Kurt Goldammer. Part I (Medical, scientific, and philosophical writings), 14 volumes (Munich and Berlin, 1922–1933). Part II (Theological and religious writings), 7 volumes (Munich and Wiesbaden, 1923–1986).

- Register zu Sudhoffs Paracelsus-Ausgabe. Allgemeines und Spezialregister: Personen, Orte, Pflanzen, Rezepte, Verweise auf eigene Werke, Bußler, E., 2018, ISBN 978-90-821760-1-8

- Theophrastus Paracelsus: Werke. Edited by Will-Erich Peuckert, 5 vols. Basel and Stuttgart: Schwabe Verlag, 1965–1968.

Selected English translations[edit]

- The Hermetic and Alchemical Writings of Paracelsus, Two Volumes, translated by Arthur Edward Waite, London, 1894. (in Google books), see also a revised 2002 edition (preview only) Partial contents: Coelum Philosophorum; The Book Concerning The Tincture Of The Philosophers; The Treasure of Treasures for Alchemists; The Aurora of the Philosophers; Alchemical Catechism.

- Paracelsus: Essential Readings. Selected and translated by Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, 1999.

- Paracelsus: His Life and Doctrines. Franz Hartmann, New York: Theosophical Publishing Co., 1918

- Paracelsus (Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, 1494–1541). Essential Theoretical Writings. Edited and translated with a Commentary and Introduction by Andrew Weeks. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2008, ISBN 978-90-04-15756-9.

- Paracelsus: Selected Writings ed. with an introduction by Jolande Jacobi, trans. Norbert Guterman, New York: Pantheon, 1951 reprinted Princeton 1988

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Pagel (1982) p. 6, citing K. Bittel, "Ist Paracelsus 1493 oder 1494 geboren?", Med. Welt 16 (1942), p. 1163, J. Strebel, Theophrastus von Hohenheim: Sämtliche Werke vol. 1 (1944), p. 38. The most frequently cited assumption that Paracelsus was born in late 1493 is due to Sudhoff, Paracelsus. Ein deutsches Lebensbild aus den Tagen der Renaissance (1936), p. 11.

- ^ Einsiedeln was under the jurisdiction of Schwyz from 1394 onward; see Einsiedeln in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ Jung, C. G. (18 December 2014). The Spirit of Man in Art and Literature. Routledge. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-317-53356-6.

- ^ Geoffrey Davenport, Ian McDonald, Caroline Moss-Gibbons (Editors), The Royal College of Physicians and Its Collections: An Illustrated History, Royal College of Physicians, 2001, p. 48.

- ^ Digitaal Wetenschapshistorisch Centrum (DWC) – KNAW: "Franciscus dele Boë" Archived 11 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Manchester Guardian, 19 October 1905

- ^ "The physician and philosopher Sir Thomas Browne". www.levity.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Josephson-Storm, Jason (2017). The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-226-40336-6. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ "CISSC Lecture Series: Jane Bennett, Johns Hopkins University: Impersonal Sympathy". Center for Interdisciplinary Studies in Society and Culture, Concordia University, Montreal. 22 March 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Josephson-Storm (2017), 238

- ^ Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Paracelsus, genannt Bombast von Hohenheim: ein schweizerischer Medicus, gestorben 1541, Hilscher, 1764, p. 13.

- ^ The name Philippus is only found posthumously, first on Paracelsus's tombstone. Publications during his lifetime were under the name Theophrastus ab Hohenheim or Theophrastus Paracelsus, the additional name Aureolus is recorded in 1538. Pagel (1982), 5ff.

- ^ Paracelsus self-identifies as Swiss (ich bin von Einsidlen, dess Lands ein Schweizer) in grosse Wundartznei (vol. 1, p. 56) and names Carinthia as his "second fatherland" (das ander mein Vatterland). Karl F. H. Marx, Zur Würdigung des Theophrastus von Hohenheim (1842), p. 3.

- ^ Allen G. Debus, "Paracelsus and the medical revolution of the Renaissance" Archived 27 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine—A 500th Anniversary Celebration from the National Library of Medicine (1993), p. 3.

- ^ "Paracelsus", Britannica, archived from the original on 25 November 2011, retrieved 24 November 2011

- ^ "Paracelsus: Herald of Modern Toxicology". Archived from the original on 24 March 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ De Vries, Lyke; Spruit, Leen (2017). "Paracelsus and Roman censorship – Johannes Faber's 1616 report in context". Intellectual History Review. 28 (2): 5. doi:10.1080/17496977.2017.1361060. hdl:2066/182018.

- ^ Duffin, C. J; Moody, R. T. J; Gardner-Thorpe, C. (2013). A History of Geology and Medicine. Geological Society of London. p. 444. ISBN 978-1-86239-356-1.

- ^ Müller-Jahncke, Wolf-Dieter, "Paracelsus" in: Neue Deutsche Biographie 20 (2001), 61–64 Archived 6 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Wear, Andrew (1995). The Western Medical Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 311.

- ^ C. Birchler in Verhandlungen der Schweizerischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft 52 (1868), 9f. A letter sent in 1526 from Basel to his friend Christoph Clauser, physician in Zürich, one of the oldest extant documents written by Paracelsus, is signed Theophrastus ex Hohenheim Eremita. Karl F. H. Marx, Zur Würdigung des Theophrastus von Hohenheim (1842), p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Johannes Schaber (1993). "Paracelsus, lat. Pseudonym von {Philippus Aureolus} Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). Vol. 6. Herzberg: Bautz. cols. 1502–1528. ISBN 3-88309-044-1.

- ^ a b c d Crone, Hugh D. (2004). Paracelsus: The Man who Defied Medicine : His Real Contribution to Medicine and Science. Albarello Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-646-43327-1.

- ^ Marshall James L; Marshall Virginia R (2005). "Rediscovery of the Elements: Paracelsus" (PDF). The Hexagon of Alpha Chi Sigma (Winter): 71–8. ISSN 0164-6109. OCLC 4478114. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2006.

- ^ Matsys' portrait may have been drawn from life, but it has been lost. At least three copies of the portrait are known to have been made in the first half of the 17th century: one by an anonymous Flemish artist, kept in the Louvre (shown here), one by Peter Paul Rubens, kept in Brussels, and one by a student of Rubens', now kept in Uppsala.

- ^ Andrew Cunninghgam, "Paracelsus Fat and Thin: Thoughts on Reputations and Realities" in: Ole Peter Grell (ed.), Paracelsus (1998), 53–78 (p. 57).

- ^ a b c Goodrick - Clarke, Nicholas (1999). Paracelsus Essential Readings. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books. p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e Borzelleca, Joseph (January 2000). "Paracelsus: Herald of Modern Toxicology". Toxicological Sciences. 53 (1): 2–4. doi:10.1093/toxsci/53.1.2. PMID 10653514.

- ^ a b c d Hargrave, John G. (December 2019). "Parcelsus". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ a b Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas (1999). Paracelsus Essential Readings. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books. p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Waite, Arthur Edward (1894). The Hermetic and Alchemical Writings of Paracelsus. London: James Elliott and Co.

- ^ "Letter From Paracelsus to Erasmus". Prov Med J Retrosp Med Sci. 7 (164): 142. 1843. PMC 2558048. PMID 21380327.

- ^ E.J. Holmyard (1957). Alchemy. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, p. 162. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Drago, Elisabeth (3 March 2020). "Paracelsus, the Alchemist Who Wed Medicine to Magic". Science History Institute. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ Webster, Charles (2008). Paracelsus: Medicine, Magic and Mission at the End of Time. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 13.

- ^ "Paracelsus". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ Pagel, Walter (1982). Paracelsus: An Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. p. 40. ISBN 9783805535182.

- ^ "Divinity School at the University of Chicago | Publications". divinity.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on 10 June 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ Ball, Philip (2006). The Devil's Doctor: Paracelsus and the World of Renaissance of Magic and Science. London: William Heinemann. p. 205.

- ^ Practica D. Theophrasti Paracelsi, gemacht auff Europen, anzufahen in den nechstkunftigen Dreyssigsten Jar biß auff das Vier und Dreyssigst nachvolgend, Gedruckt zu Nürmberg durch Friderichen Peypus M. D. XXIX. (online facsimile) Archived 12 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pagel (1982), p. 5ff.

- ^ Ingrid Kästner, in Albrecht Classen (ed.), Religion und Gesundheit: Der heilkundliche Diskurs im 16. Jahrhundert (2011), p. 166.

- ^ Pagel (1982), p. 26.

- ^ Dominiczak, Marek H. (1 June 2011). "International Year of Chemistry 2011: Paracelsus: In Praise of Mavericks". Clinical Chemistry. 57 (6): 932–934. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2011.165894. ISSN 0009-9147.

- ^ Joachim Telle, "Paracelsus in pseudoparacelsischen Briefen", Nova Acta Paracelsica 20/21 (2007), 147–164.

- ^ a b c Pagel, W. (1982). Paracelsus: An Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance. S. Karger. pp. 54–57.

- ^ a b Jacobi, J. (1995). Paracelsus - Selected Writings. Princeton University Press. pp. 71–73.

- ^ a b c d Borzelleca, J. (2000). Profiles in Toxicology - Paracelsus: Herald of Modern Toxicology. Toxicological Sciences. pp. 2–4.

- ^ Habashi, Fathi. Discovering the 8th metal (PDF). International Zinc Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2015..

- ^ Hefner Alan. "Paracelsus". Archived from the original on 21 December 2005. Retrieved 28 October 2005.

- ^ a b c d Borzelleca, Joseph F. (1 January 2000). "Paracelsus: Herald of Modern Toxicology". Toxicological Sciences. 53 (1): 2–4. doi:10.1093/toxsci/53.1.2. ISSN 1096-6080. PMID 10653514.

- ^ John S. Rigden (2003). Hydrogen: The Essential Element. Harvard University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-674-01252-3.

- ^ Doug Stewart. "Discovery of Hydrogen". Chemicool. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ^ a b Pagel, Walter. Paracelsus; an Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance. Basel: Karger, 1958. Print.

- ^ Silver, Carole B. (1999). Strange and Secret Peoples: Fairies and Victorian Consciousness. Oxford University Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-19-512199-6.

- ^ Paracelsus (1996). Four Treatises of Theophrastus Von Hohenheim Called Paracelsus. JHU Press. p. 222.

- ^ Kahn, Didier (2016). Unifying Heaven and Earth: Essays in the History of Early Modern Cosmology. Universitat de Barcelona.

- ^ a b c d e Webster, Charles. Paracelsus: Medicine, Magic and Mission at the End of Time. New Haven: Yale UP, 2008. Print.

- ^ Boyle 1661, p. 23-24.

- ^ Boyle 1661, p. 36.

- ^ The sculpture shows an "Einsiedeln woman with two healthy children" (Einsiedler Frau mit zwei gesunden Kindern) as a symbol of "motherly health". A more conventional memorial, a plaque showing the portrait of Paracelsus, was placed in Egg, Einsiedeln, in 1910 (now at the Teufelsbrücke, 47°10′03″N 8°46′00″E / 47.1675°N 8.7668°E). The 1941 monument was harshly criticized as "dishonest kitsch" (verlogener Kitsch) in the service of a conservative Catholic "cult of motherhood" (Mütterlichkeitskult) by Franz Rueb in his (generally iconoclastic) Mythos Paracelsus (1995), p. 330.

- ^ Wear, Andrew (1995). The Western Medical Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 314.

- ^ a b Wear, Andrew (1995). The Western Medical Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 315.

- ^ Alex Wittendorff; Claus Bjørn; Ole Peter Grell; T. Morsing; Per Barner Darnell; Hans Bjørn; Gerhardt Eriksen; Palle Lauring; Kristian Hvidt (1994). Tyge Brahe (in Danish). Gad. ISBN 87-12-02272-1. p44-45

- ^ Helm, J.; Winkelmann, A. (2001). Religious Confessions and the Sciences in the Sixteenth Century. Studies in European Judaism, Volume 1. Brill. p. 49. ISBN 978-90-04-12045-7. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ Dorner, I.A. (2004). History of Protestant Theology. Wipf & Stock Publishers. p. 1-PA179. ISBN 978-1-59244-610-0. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ Hargrave, J. (1951). The Life and Soul of Paracelsus. Gollancz. Archived from the original on 3 January 2024. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ Brockliss, L.W.B.; Jones, C. (1997). The Medical World of Early Modern France. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822750-2. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ Sigerist, H. E. (1941). "Laudanum in the Works of Paracelsus" (PDF). Bull. Hist. Med. 9: 530–544. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ Michael Quinion, World Wide Words, May 27, 2006 Archived 31 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF PARACELSUS TO MEDICAL SCIENCE AND PRACTICE J. M. Stillman The Monist, Vol. 27, No. 3 (JULY 1917), pp. 390–402

- ^ "Short History of Fasting | Jun 05, 2017". Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ Natura Sophia. Paracelsus and the Light of Nature Archived 22 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 26 November 2013

- ^ Corn, Jacqueline K. (1975). "Historical Perspective to a Current Controversy on the Clinical Spectrum of Plumbism" (PDF). Milbank Quarterly. 53 (1): 95. PMID 1094321. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Paracelsus, dritte defensio, 1538.

- ^ a b Hanegraaf, W. (2007). Paracelsus (Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, 1493-1541). Brill. pp. 509–511.

- ^ Ehrenwald, Jan (1976), The History of Psychotherapy: From Healing Magic to Encounter, Jason Aronson, p. 200, ISBN 9780876682807, archived from the original on 3 January 2024, retrieved 19 October 2020

- ^ Werneck in Beiträge zur praktischen Heilkunde: mit vorzüglicher Berücksichtigung der medicinischen Geographie, Topographie und Epidemiologie, Volume 3 (1836), 212–216 Archived 26 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Neues Journal zur Litteratur und Kunstgeschichte, Volume 2 (1799), 246–256.

- ^ The von Hohenheim arms showed a blue (azure) bend with three white (argent) balls in a yellow (or) field (Julius Kindler von Knobloch, Oberbadisches Geschlechterbuch vol. 1, 1894, p. 142 Archived 24 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine), i.e. without the border. Franz Hartmann, Life and Doctrines (1887), p. 12 describes the arms shown on the monument in St Sebastian church, Salzburg as "a beam of silver, upon which are ranged three black balls".

- ^ F. A. Yates, Rosicrucian Enlightenment (1972), p. 120.

- ^ Huser quart edition (medicinal and philosophical treatises), ten volumes, Basel, 1589–1591; Huser's edition of Paracelsus's surgical works was published posthumously in Strasbourg, 1605.

- ^ Eugen Weber, Apocalypses: Prophecies, Cults, and Millennial Beliefs Through the Ages (2000), p. 86.

- ^ C.W.C.G.Jung vol.15 'The Spirit of Man, Art and Literature' pub.RKP 1966

- ^ Un médecin d'autrefois. La vie de Paracelse, Paris (1830), reprinted 1838, German translation by Eduard Liber as Theophrastus Paracelsus oder der Arzt : historischer Roman aus den Zeiten des Mittelalters , Magdeburg (1842).

- ^ Paracelsus (1835)

- ^ The sword was said to contain the philosopher's stone in its pommel, and Morell's tale concerns Paracelsus's death (due to his being interrupted during the casting of a spell against poisoning) and his command that the sword should be thrown into the Sihl river after he dies. Meinrad Lienert, "Der Hexenmeister" in: Schweizer Sagen und Heldengeschichten, Stuttgart (1915).

- ^ Udo Benzenhöfer, "Die Paracelsus-Dramen der Martha Sills-Fuchs im Unfeld des 'Vereins Deutsche Volksheilkunde' Julius Streichers" in Peter Dilg, Hartmut Rudolph (eds.), Resultate und Desiderate der Paracelsus-Forschun (1993), 163–81.

- ^ "NY Times: Paracelsus". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2012. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ^ p. 73.

- ^ "Indigo's Delivery: An Excerpt from the Rose of Paracelsus". 16 April 2018. Archived from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

General and cited references[edit]

- Boyle, R. (1661). The Sceptical Chymist: or Chymico-Physical Doubts & Paradoxes, Touching the Spagyrist's Principles Commonly call'd Hypostatical; As they are wont to be Propos'd and Defended by the Generality of Alchymists. Whereunto is præmis'd Part of another Discourse relating to the same Subject. Printed by J. Cadwell for J. Crooke.

Further reading[edit]

- Ball, Philip. The Devil's Doctor. ISBN 978-0-09-945787-9. (Arrow Books, Random House.)

- Debus Allen G. (1984). "History with a Purpose: the Fate of Paracelsus". Pharmacy in History. 26 (2): 83–96. JSTOR 41109480. PMID 11611458.

- Forshaw, Peter (2015). "'Morbo spirituali medicina spiritualis convenit: Paracelsus, Madness, and Spirits", in Steffen Schneider (ed.), Aisthetics of the Spirits: Spirits in Early Modern Science, Religion, Literature and Music, Göttingen: V&R Press.

- Thomas Fuller (1642). The Holy State. p. 56.

- Hargrave, John (1951). The Life and Soul of Paracelsus. Gollancz.

- Franz Hartmann (1910). The Life and the Doctrines of Paracelsus.

- Moran, Bruce T. (2005). Distilling Knowledge: Alchemy, Chemistry, and the Scientific Revolution (Harvard Univ. Press, 2005), Ch. 3.

- Pagel, Walter (1982). Paracelsus: An Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance (2nd ed.). Karger Publishers, Switzerland. ISBN 3-8055-3518-X.

- Senfelder, L. (1911)."Theophrastus Paracelsus". The Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Stoddart, Anna (1911). The Life of Paracelsus. J. Murray.

- Webster, Charles (2008). Paracelsus: Medicine, Magic, and Mission at the End of Time (Yale Univ. Press, 2008).

External links[edit]

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Online bibliographies and facsimile editions

- Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz)

- Digital library, University of Braunschweig

- Zürich Paracelsus Project

- Dana F. Sutton, An Analytic Bibliography of Online Neo-Latin Texts, Philological Museum, University of Birmingham—A collection of "digital photographic reproductions", or online editions of the Neo-Latin works of the Renaissance.

- Works by Paracelsus (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek)

- Images from Prognosticatio eximii doctoris Theophrasti Paracelsi—From The College of Physicians of Philadelphia Digital Library

- Azogue: A section of the e-journal Azogue with original reproductions of paracelsian texts.

- MS 239/6 De tartaro et eius origine in corpore humano at OPenn

- Other

- Paracelsus

- 1493 births

- 1541 deaths

- 16th-century alchemists

- 16th-century astrologers

- 16th-century writers in Latin

- 16th-century occultists

- 16th-century Swiss physicians

- 16th-century Swiss scientists

- 16th-century Swiss writers

- Paracelsians

- People from Einsiedeln

- Swiss alchemists

- Swiss astrologers

- Swiss non-fiction writers

- Swiss toxicologists

- University of Ferrara alumni

- People associated with the University of Basel

- Plague doctor